Abstract

Most national level referendums in Europe since 1793 are initiated either by political elites or by citizens. It remains unclear why these two types of initiators call for referendums. This article aims to explain under what circumstances political elites and citizens call referendums on domestic policies. The analysis is conducted at country level using an original data set that covers 461 national level referendums in Europe between 1793 and 2019. It tests the influence of four institutional variables that in theory are expected to have a divergent effect for the two types of initiators. The experience with direct democracy increases the likelihood to have referendums called by elites and reduces the incidence of citizen-initiated referendums. More authoritarian countries and longer time passed from referendums in a neighboring country explain why political elites initiate referendums. Coalition governments are more prone to citizen-initiated referendums on domestic policies compared to single-party governments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The use of national-level referendums has gained momentum in the last three decades (Altman 2011; Qvortrup 2014b; Morel and Qvortrup 2017). Throughout the world, an increasing number of topics is subjected to popular vote ranging from very specific issues such as the number of parliamentarians in the legislature to broad issues such as state formation or the withdrawal from the European Union. Unless they are required by law, i.e., mandatory, referendums provide their initiators the possibility to frame the policy agenda. Statistically speaking, many referendums have been initiated either by political elites or by citizens. In Europe, out of the national-level referendums organized between 1793 and 2019 roughly one quarter were mandatory, i.e., demanded by law. The rest is almost evenly divided between the two initiators: 238 referendums were initiated by political elites and 223 by citizens. In the face of this extensive use of referendums, the big question mark is why these initiators call referendums.

So far, research has touched upon this question but has not provided a comprehensive answer. This is because it focused either on the local level, on single-case or single policy and on the reasons behind one type of initiators. First, earlier studies looked at causes of citizens’ initiatives and referendums at local level, which provide valuable insights about particular processes but cannot be generalized at national level (Bowler and Donovan 2000; Gordon 2009; Schiller 2011; Laisney 2012). Second, much attention has been paid to the ways in which single policies such as the European integration or independence have triggered the use of referendums (Hobolt 2009; Mendez et al. 2014). Single-case studies have added substantial findings to the debate about causes for which referendums are initiated (Kriesi 2005; Elkink et al. 2017; Bergman 2019), but their thorough contextual explanations lack generalizability, Third, earlier studies looked at the two types of initiators separately. On the one hand, much has been written about the strategic motives of politicians calling referendums to maximize their power, control the policy agenda, seek electoral support or gain legitimacy (Björklund 1982; Walker 2003; Rahat 2009; Gherghina 2019). On the other hand, the demands of citizens toward referendums have been usually studied as a reaction to what politicians do or as a way to promote a salient issue on the public agenda (Bowler and Donovan 2002; Setala and Schiller 2012).

This article seeks to go beyond these approaches and explain under what circumstances political elites and citizens call national level referendums on domestic policies in Europe. By political elites, we understand the representatives elected in high office at central level, e.g., head of state, prime minister, cabinet members, or members of parliament. In the attempt to overcome the limitations of the three strands of literature mentioned above, the article aims to compare and contrast the causes for these two types of initiators on the same policy area, i.e., domestic policies. These are defined as issues related to constitution, political / electoral system and interior policies (Silagadze and Gherghina 2020). The analysis is conducted at country level using an original data set that covers 461 national level referendums in Europe between 1793 and 2019, initiated either by elites or by citizens.Footnote 1 The referendums on domestic policies are more than half (235) of the total. We argue that four institutional variables can explain the use of referendums on domestic policies: the number of parties in government, the degree of democracy in the country, the experience with referendums and the institutional learning / contagion effect. We expect to observe different effects for the two initiators because, as explained in the following section, political elites and citizens have different sets of incentives. In addition to these four main effects, we also control for the ideology of the government and external shocks since they have been identified by earlier studies as potential drivers for referendums. The analysis goes beyond earlier explanations about the occurrence of referendums relative to the legislative provisions (Hug 2004). We look at the referendums that were organized—and thus for which legislation is in place—and we seek to understand the circumstances that favor their use from two different perspectives: politicians and citizens.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The first section reviews the literature about top-down (elite driven) and bottom-up (citizen driven) referendums. It also proposes several theoretical arguments that could explain the use of referendums by the two initiators and formulate four testable hypotheses. Next, we present the research design with emphasis on the data, variable measurements and methods used for analysis. The third section includes the analysis and interpretation of results, linking the findings to the theoretical underpinning from the literature. The conclusions summarize the key results and discuss the main implications.

Elite versus citizen-initiated referendums

The use of referendums has increased over time. The legal provisions for referendums and initiatives vary considerably across countries, making direct comparisons tricky (Qvortrup 2018). In 2016, out of the 195 independent countries in the world, only 37 had no provisions for national referendums (Morel 2018). Institutional provisions for citizens’ initiatives are being increasingly added to new constitutions; however, compared to the referendum tool, initiative is far from being universally accessible mechanism. Many post-communist countries and only four countries in Western Europe have provisions for it (Serdült and Welp 2012). The distinction between “top-down” (elites) and “bottom-up” (citizens) referendums, introduced by Papadopoulos (1995), refers to the source of initiation: the former is initiated by the ruling elite, and the latter is triggered by popular minorities through collection of citizens’ signatures. Bottom-up referendums come in two forms: either a new piece of legislation is put forward—popular initiatives or a previously passed legislation is challenged—abrogative and rejective referendumsFootnote 2 (Kaufmann et al. 2010).

Elite and citizen-initiated referendums differ in their nature, functions, and consequences. Popular votes organized by the elite often seek additional legitimacy for policies molded within representative institutions. Once a policy takes the referendum hurdle, it acquires more legitimacy and credibility, since its support extends beyond the parliamentary circle (Papadopoulos 1995, p. 433). Apart from gaining legitimacy top-down referendums are applied as a tool for mediation in order to settle conflicts within parties or coalitions over a contradicting issue and thus, uncouple it from future electoral campaigns, to enhance one’s political influence via showing a wide popular support for the suggested policy (Björklund 1982; Rahat 2009). Consequently, top-down referendums are held infrequently and only in the situations where the government considers it as an useful ad hoc solution to a certain constitutional or political problem (Butler and Ranney 1978).

Citizen-initiated referendums, in contrast, can reflect some disagreement with the outcome of policies designed by the representative system. Bottom-up democracy allows citizens to become veto players in the process of changing legislative status quo (Hug and Tsebelis 2002). Popular initiatives allow citizens to become innovators by proposing a new pieces of legislation or raising a neglected policy (Serdült and Welp 2012). Accordingly, they are viewed as a disruptive process by those in power since “popular initiatives introduce a dose of uncertainty and unexpectedly upset the political agenda,” while for citizens, it is another means of making their voice heard (Papadopoulos 1995). Hence, bottom-up democracy contributes to citizens’ empowerment, supports responsiveness and accountability reducing the distance between citizens’ preferences and actions of their representatives (Schiller 2012).

As a consequence, a similar effect is observed in political systems where direct-democratic procedures from below are broadly used—the general trend toward consensus, integrating various interests and opposition groups into the decision-making process (Papadopoulos 2001; Marxer and Pallinger 2009). Besides, studies show that the level of satisfaction with the development of the country and its perceived legitimacy by the citizens is positively affected by the availability of referendum options (Hug 2005; Gherghina 2017).

Depending on the function that a single referendum fulfills for its initiator, different typologies have been introduced. Some differentiate between decision-controlling and decision-promoting referendums (Gallagher 1996). Decision-promoting referendums are typically initiated by a political actor seeking to have their proposal approved. Decision-controlling referendums, on contrary, are seen as a check mechanism on a legislative change since they are not initiated by the proposer of the policy that is voted upon. Elite-initiated referendums usually fall within the category of decision-promoting referendums. Citizen-initiated votes exhibit features of both: popular initiatives that put forward a new piece of legislation serve as a decision-promoting tool, while abrogative and rejective referendums that challenge previously passed legislation—as decision-controlling.

There is a distinction in the literature between controlled and uncontrolled referendums that are either pro-hegemonic or anti-hegemonic (Smith 1976). In most cases, bottom-up referendums fall under uncontrolled and anti-hegemonic since their whole point is to bring about changes that are resisted by the government, while most top-down referendums fall under controlled (by elite) and pro-hegemonic—strengthening their position. There is some sort of consensus among the scholars that the most powerful and important tool of direct democracy is the popular initiative that has the strongest anti-hegemonic character even compared to other bottom-up processes. Originating in part of the electorate—not a political institution, this instrument of “popular law-making” is a dynamic means to chip into the decision-making process from outside, bypassing the gatekeepers—established parliamentary channels (Papadopoulos 1995, 2001; Marxer and Pallinger 2009).

However, referendum initiation is a costly endeavor that requires high financial and human resources. In all types of referendum, elite and political parties continue to play a central role, the only difference being the level of control and nature of limitations (Rahat 2009). Referendums are often influenced by various interest groups, NGOs, trade unions or the church. Moreover, in some cases, even popular initiatives are organized by established political parties after failing to achieve their objectives via representative channels. For instance, the Ukrainian referendum in 2000 seeking to reinforce presidential powers originated from a collection of signatures. However, the process was organized by the country president and his supporters (Serdült and Welp 2012).

Hypotheses

This brief literature review indicates that elite- and citizen-initiated referendums rest on different logics. Accordingly, we expect the same factors to have contrasting effects on the likelihood for referendums initiated by elites or by citizens. This sub-section argues and tests the potential impact of four variables: government composition, degree of democracy, experience with the use of referendums and contagion effect. All hypotheses marked with “a” are for the elites, while those with “b” are for citizens.

To start with the government composition, the essential distinction lies between a single- and multi-party government. Being in government allows politicians to decide and implement policies. Many political parties seek a good performance in office that can ensure re-election and eventually continuity in office (Sartori 1976; Gunther and Diamond 2003). Parties have control over policies and have more opportunities to forge a positive image among the electorate when they form the government alone. They have a high level of policy influence that can make people recognize when they fulfill their election pledges (Pétry and Duval 2018). Parties that do not share the power may resort to referendums to alter domestic policies both when they have a parliamentary majority and when they are in minority. When single government parties are backed by parliamentary majority, they can use referendums to illustrate that the opinion of the public matters. Although they have the power to make any changes with the help of majority, the referendums ensure the component of popular legitimacy. When there is a minority single party government, its elites may use referendums to bypass an adversarial legislature (Gherghina 2017). In situations with single-party government, opposition parties may also be inclined to propose referendums to counter-balance the government strength and seek to amend legislation in other ways than in parliament.

In coalition governments, there is uncertainty between the partners and commitment problems occur often (Bäck and Lindvall 2015). Coalition partners find it difficult to reach consensus over policies due to ideological differences or policy priorities. Negotiations and compromise among the coalition partners do not necessarily lead to policy agreement, which often result in no change (Fischer 2014). In such a situation, the population may step in and initiate a referendum to achieve the policy change. Moreover, due to ideological differences within coalitions, the partners cannot conduct consistent campaigns. For example, if the government elites call for a referendum, the coalition may not belong to the same camp (Qvortrup 2018; Gherghina 2019). Each party will seek to mobilize their electorate, which will result in different vote choices if the parties have diverging interests. Opposition parties may also be reluctant to call for referendums because the classic division with government parties will not be obvious. Under these circumstances, citizens may use referendums to articulate their policy preferences, to move beyond the partisan inactivity. Consequently, we expect that:

H1a

A single-party government favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by political elites.

H1b

A coalition of parties in government favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by the citizens.

The level of democracy is expected to influence the use of direct-democratic tools. In non-democratic countries, referendum is another piece of the authoritarian machinery, as rigged as elections (Morel 2018). Accordingly, referendum is used serves solely for the purpose of guarding the interests of the ruler, enhancing their power and simultaneously demonstrating their legitimacy, both domestically and internationally (Qvortrup 2017). The nations in transition are different because they undergo a simultaneous threefold transformation: territorial, political and economic (Offe 1991). With the ongoing large-scale system change, only major policies related to substantial political, electoral or constitutional matters are subjected to popular vote. According to the dataset used in this article (see the research design), in those countries, 13% of all referendums are initiated by citizens. These are transitions from repressive regimes and thus with underdeveloped civil society.

In the case of democracies, we expect different mechanisms. First, an increasing number of democratic countries adopted provisions for bottom-up referendums serving as safety valves of political pressure (Altman 2011). Moreover, established democracies dispose the necessary cultural prerequisites for active citizen participation—well-developed civil society structures with strong network of grassroots organizations. Besides, most of the developed societies have experienced shift of values toward post-materialism and one of its components is participatory element (Inglehart 1989). Democracies offer an appropriate framework for bottom-up activities: they are designed in such a way that its members have a say in politics. As such, the referendum is not monopolized by one political actor but also used by various groups, including institutional minorities (opposition parties). The latter have legal and institutional instruments to become active agents in the decision-making process by articulating their interests and mobilizing citizens. Following this line of argumentation, we hypothesize that:

H2a

Less democratic countries are likely to use top-down referendums on domestic policies by political elites.

H2b

More democratic countries are likely to use bottom-up referendums on domestic policies.

Lijphart (1984) argued three decades ago that governments that control the referendum will use it when they expect to win. If policy-makers associate referendums with an efficient tool of decision-making process, they are more likely to apply it frequently. A recent study of national level referendums held in the last two centuries shows that this is empirically the case in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian regimes. In these two types of regimes, the referendums are adopted in 95%, respectively, 80% of cases (Silagadze and Gherghina 2020). Such a rate of adoption suggests the self-reinforcing circle: elite initiate referendums, they mostly win them that encourages them to initiate more. Another argument for which experience with referendums is likely to encourage the political elites to use more referendums is that the use of referendums can be a source of subjective regime legitimacy in Europe (Gherghina 2017). The results indicate that when people have the possibility to vote in referendums, they trust more the regime and comply with the role of their institutions. Politicians have the reasons to continue this tradition of referendums in order to maintain a high level of legitimacy among citizens.

In societies or times when referendums are not frequently used, this might become an appealing instrument for citizenry to check on the representative system, to supply input from the grassroots. There may be various reasons for rare use of referendums—among others if the elite does not view it as the best means to coming to the desired outcome or if no consensus could be reached over its application. In addition, having a touch of novelty, citizens might feel more optimistic and eager to make use of initiatives. Accordingly, we expect that:

H3a

High experience with referendums favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by political elites.

H3b

Less experience with referendums favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by citizenry.

Political events in neighboring countries may matter. There are two reasons why policy-makers and citizens could pay attention to politics of their neighbors: (1) they share some common values, are familiar with the culture, and enjoy cross-mixing of media; (2) neighboring countries compete between each other trying to maintain the same level of services (Mooney 2001). Moreover, one source of policy change is the policy-oriented learning that is achieved either by the evaluation of former policies or the evaluation of policies from abroad (Sabatier 1987, 1998). The latter can be reflected in a potential influence that referendums on a similar policy might have for the neighboring country. Elites are often quite hesitant or cautious to follow the example of neighboring countries. It is in their interest to let time pass and observe the consequences of referendums to optimize the learning effect. This holds true for both scenarios: if the referendum was adopted, the elites can assess the implementation and its effects on the system; if it failed, the elites can evaluate what went wrong and what mistakes to avoid in similar referendums. Since the instrument of direct democracy is easily available, there is no need for the elite to haste and mimic the actions of their neighbors promptly.

The dynamic of citizen-initiated referendums is the opposite. Due to vast human and financial resources required by such referendums, the civil society has a good chance to mobilize the electorate when the topic is salient and widely discussed in the media, usually in the aftermath of a referendum in a neighboring country. The ongoing debate helps to agitate and mobilize interest groups, people are eager and inspired to act immediately. As the time passes, the interest might fade with it. Thus, we expect that:

H4a

Longer time passed from a referendum on a similar topic in a neighboring country favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by political elites.

H4b

A recent referendum on a similar topic in a neighboring country favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by citizens.

Controls

In addition to these main effects, we also test for two control variables: ideology of the party in government and external shocks. These are considered by earlier studies as potential determinants for policy change and referendum process, but no clear causal relationship has been identified. There is an extensive literature devoted to various topics around ideology and its influence on policy outcomes. There are certain topics that are closer either to the left or right camp, for instance, left-wing prioritize public welfare over economic growth, while right-wing parties place economic growth in a more important position (Wen et al. 2016). An analysis of 25 countries between 1945 and 1998 shows that the left put emphasis on peaceful internationalism, welfare, expansion of education and government intervention, while the right focused on strong defense, free enterprise and traditional morality (Budge and Klingemann 2001).

Shocks and crises may play a pivotal role in policy change and referendum is just one means of the policy change. According to Grossman (2015), “typically, the process [of change] begins with a notable exogenous event, a shock. Often, the shock leads to what is perceived to be a crisis”. Keeler (1993) explains: “A crisis can create a sense of urgency … [that] allows for unusually rapid acceptance of reform proposals intended to resolve the crisis.” Various studies show that major policy changes were preceded by a notable external stimulus (Nohrstedt and Weible 2010; Grossman 2015). Saurugger and Terpan (2016) confirm that the more severe the crisis, the bigger is the window for changes.Footnote 3

Research design

To test these effects, we use an original dataset consisting of all 461 elite and citizen-initiated referendums at national level held between 1793 and 2019 in Europe. Similar to earlier studies (Qvortrup 2014a; Gherghina 2019), this article considers a referendum as corresponding to one policy decision that citizens have to make. One referendum is one question to which the citizens have to answer on the ballot. If there are more questions asked the same day, we count them as different referendums. This conceptualization allows us to separate between referendums with different initiators (elite vs citizens) organized the same day. The distribution of referendums across the two types of initiators is almost equally split: 238 were initiated by the elites and 223 were called by citizens. There are 43 countries included in the analysis out of which two no longer exist as countries: Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union.Footnote 4 The unit of analysis is the national referendum, and all variables were collected and analyzed at this level. The analyzed referendums form the entire universe of cases, and they are not a sample. All the results presented in this article reflect the reality in Europe, without running the danger of not being generalizable.

The area selected for analysis is domestic policies, which includes the constitutional, political system and interior policy categories. The logic behind this grouping refers to the general political architecture of the society with its fundamental norms and principles anchored in the constitution, to more specific regulations and practices manifested in the interior legislation, and to the “rules of the game” defining the political and electoral landscape. The theoretical reasons behind this selection is that this policy area includes many salient policies for both elites and citizens. The latter are likely to make their voice heard in policies that immediately affect their life. The empirical reason behind the selection is that roughly half of all referendums called since 1793 are on domestic policies (235 out of 461). Among the elite-initiated referendums, they represent 54% of the total (129 out of 238), while among the citizen-initiated referendums, the ones on domestic policies are 48% (106 out of 223). The other policy areas in which referendums were called throughout history are international system (including foreign affairs), welfare policies, and post-materialist issues—environmental topics, questions related to media and moral/ethical issues (Silagadze and Gherghina 2020).Footnote 5

The dependent variable of this study is the initiation of a referendum in the area of domestic policies. This is coded dichotomously with 1 for all instances in which such a referendum was called and 0 when referendums on other topics were called. The first independent variable is the number of parties in government (H1) and it is coded as a dummy variable with value 1 for a single party in government and 2 for a coalition of parties. Ideally, the coding could differentiate between the number of parties in the coalition. This is a very difficult task because for some coalitions—especially in the early twentieth century—there is no information about the composition of government. In other cases, there was contradictory information about the number of parties in government and no reliable source could be followed. Many authoritarian regimes were coded as a single-party government since in such institutional settings government speaks with one voice, political pluralism is non-existent. The technocratic governments were dropped from the analysis because they are dominated by independent members of cabinet. For example, the referendums organized in Russia in the end of 1993 was under a government appointed by the state president after a political crisis in the fall of the same year. The vast majority of cabinet members did not belong to political parties.

The degree of democracy (H2) is an ordinal measure on a three-point scale: 1 for authoritarian regimes, 2 for transition countries and 3 for democracies. The point of reference is the moment at which the referendum takes place. The assessment is based on a plurality of sources such as the established indices of Freedom House, V-dem and Polity IV. For all countries that are not covered by these indices, we use a review of the secondary literature covering case studies or the opinions of scholars in those countries (e.g., historians, political scientists). The experience with referendums (H3) is a dichotomous variable coded with 1 if the country organized referendums in the previous five years and 0 if no such referendum was organized.

The contagion effect (H4) is measured as the time elapsed between the referendums in a neighboring country in the last five years. The variable is coded on a six-point ordinal scale with the following values: no referendum (0), referendum five years before (1), referendum four years before (2), referendum three years before (3), referendum two years before (4), referendum the year before (5) and referendum the same year (6). This measurement seeks to capture a potential influence of a neighboring country on the decision to call for a referendum. For both variables in H3 and H4, we use a five-year period imitation or influence as it is difficult to assess beyond this point. We checked the methodological robustness of this threshold by altering the values (e.g., 4, 6, 7, etc.), and there are similar results.

The first control variable is government ideology, measured on a nine-point ordinal scale that corresponds to the party families. The scale ranges between extreme left (1) and extreme right (9). Most data come from the ParlGov database, and for cases that are not included in the database, we use secondary literature and experts, i.e., political scientists from those countries. For single-party government, the ideology is usually straightforward. For coalitions, we use the ideology of the formateur when there is a large or dominant party in the coalition. If there are two parties with relatively equal strength, we use the average of their ideological stances; these are rare cases and usually the parties are ideologically quite close. We drop the cases in which the government ideology is difficult to determine, e.g., referendums in San Marino before 1906 since the first parliamentary elections took place that year; until then, the country was governed by a Council composed by the heads of the Great families.

The second control variable refers to the existence of external shocks that could have determined the elites or citizens to call for a referendum. An example of external shock is the disintegration of a federation, which asks for independence referendums. The external shocks are coded dichotomously: 1 if there is one during three years prior to the referendum, 0 for no external shock. The time frame for external shocks is shorter than for contagion effect due to the nature of shocks that demand / require immediate reaction in order to prevent a more severe crisis; the time span for lagged effect is rather curtailed. The variation for each variable is available in “Appendix 1” for the elite-initiated referendums and in “Appendix 2” for the citizen-initiated referendums.

The empirical testing presented in the following section proceeds in two steps. We start the analysis with a bivariate correlation that allows us to draw some preliminary conclusions about the relationships between the variables. The presented coefficients are the result of nonparametric correlations due to the ordinal measurement of most variables. We continue with a binary logistic regression with two separate models for each of the two types of referendums: one without and one with controls. The regression coefficients are odds ratios for a simpler interpretation of results.

Government composition, democracy and experience with referendums

The theoretical section argues that there are reasons to expect that political elites and citizens call referendums under different circumstances. In practice, for the national-level referendums in Europe, the effects are similar for half of the hypotheses. The correlation coefficients in Table 1 indicate that fewer parties in government, authoritarian countries, more experience with referendums and the longer time passed from a similar referendum in a neighboring country favors the use of referendums by the elites. There is fairly limited evidence for H1a in the expected direction, and the relationship is weak. The empirical support for H2a is the strongest, being also statistically significant at the 0.01 level. Since the analysis includes the entire universe of cases, the statistical significance cannot be used to generalize from the sample to the broader population but instead can be meaningful for the future addition of new cases. The statistically significant relationships could predict more reliably what will happen when new referendums are initiated. The controls indicate that right leaning governments are slightly more likely to accommodate elite-driven referendums. The absence of external shocks also favors elite-driven referendums, the correlation coefficient having a similar size with the contagion effect (or its absence), being also statistically significant.

For the citizens-initiated referendums on domestic policies, the coefficients provide strong empirical support only for one hypothesis: less experience with referendums (H3b). There is weak empirical support for H1b according to which coalition governments favor the existence of more bottom-up referendums on domestic policies. However, the coefficient is fairly small. The other two variables go against the hypothesized direction: less democratic countries have more referendums called by citizens unlike what expected in theory (H3b). This result is driven by the fact that all citizen-initiated referendums in transition countries were on domestic policies. In democracies citizens called referendums on various topics. Similarly, the longer time passed from a referendum on a similar topic in a neighboring country in the previous five years favors the emergence of a bottom-up referendum (H4). This happens to a lower extent than in the case of elite-initiated referendums, but in the same direction. The government ideology and external shocks are not statistically related to the extent to which citizens call for domestic policy referendums in Europe.

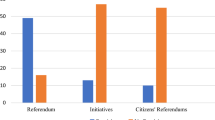

We run two separate models of binary logistic regression: one without controls (Model 1) and one with controls (Model 2), presented in details in “Appendix 3..” Figure 1 depicts the effects for Model 2. The results confirm to a great extent the results of the bivariate correlations but there are also some nuanced findings. One of these is that the first hypothesis finds empirical support only for the referendums called by citizens (H1b). The data indicates that coalition governments are more favorable across the board to referendums on domestic policies compared to single-party governments. This happens with citizen-initiated referendums, as expected in theory, but also with the referendums initiated by the political elites. Citizens are 1.5 times more likely to call for a referendum on domestic policies under a coalition government, while political elites are roughly two times more likely to do so (Fig. 1). One explanation for this finding is that not only the government initiates referendums, but also the parliament or the president. Even if the government is composed of one party and decides not to call for a referendum, the parliamentary opposition or the country president—especially if it is a situation of co-habitation in which the president comes from another party than the head of the cabinet—can call referendums. Another explanation is that coalition governments have a plurality of voices and some of these may wish to submit issues to referendums. For example, this is the case with the 2015 referendum against same-sex marriage in Slovakia where the Christian-Democrats, the minor coalition partner, pushed for it. They were supported by the larger social democratic partner who in theory have a different opinion on the matter, i.e., equality, inclusion.

The regression analysis finds empirical support forH2a according to which in less democratic countries the political elites are more likely to call for domestic policy referendums. The latter plays the role of legitimizing tools for the political elites, and they are willing to use them especially in a context in which citizens do not have the right to initiate referendums. There is no effect of a country’s democracy status on the likelihood to have citizens calling for referendum on domestic policies. One possible explanation for the lack of a relationship is the empirical observation from our dataset according to which in democracies citizens initiate referendums on a variety of topics. The data for the 461 referendums shows that out of a total of 212 bottom-up referendums in democratic countries, 117 were on other topics than domestic policies. This happens because areas concerning domestic policies are functional and regulated by the political system in democracies, and referendums do not have to be called by citizens. The absence of citizen-initiated referendums in authoritarian countries adds to the general picture.

Hypotheses H3a and H3b find empirical support as described in the theoretical section. Figure 2 illustrates the divergent effects that experience of referendums has for the two types of referendums. Both axes are on a 0–1 scale, and the marginal effect is straightforward to interpret. In countries where other referendums were organized in a time frame of five years, the political elite is 1.5 times more likely to call a referendum on domestic policies compared to other types of policies. Under similar conditions, the citizens are 1.5 times less likely to call a referendum on domestic policies compared to other types of policies.Footnote 6 When referendums on domestic policies are already organized by the elite, citizens might redirect their attention to other salient topics. For instance, Italy held a top-down referendum in 2001 on greater legislative powers to the regions. The subsequent referendums initiated by the citizens targeted completely different areas: unjustified dismissals in small enterprises (2003) or embryonic research and artificial insemination (2005).

The evidence indicates that the longer time passed from a referendum on a similar topic in a neighboring country favors the use of referendums on domestic policies by political elites (H4a). This indicates that politicians adapt to the situation in the country rather than being inspired and replicating the behavior of their neighbors. This is applicable at least with respect to domestic policies. For instance, the Icelandic referendum of 2012 on a new constitution was completely isolated from the politics in the neighboring countries and had internal reasons. For nearly 70-years, Iceland’s political elite did not revise the 1944 provisional constitution. In the wake of protests in late 2008 and early 2009, the process of constitutional revision was initiated and people had a popular vote on the new constitution several years later. The same pattern, but with a smaller effect size, can be observed for citizen-initiated referendums. One explanation for which this goes against the hypothesized relationship is that it takes time to mobilize citizens especially when different interest groups are involved. In addition, many hurdles have to be overcome before a referendum can take place: after collecting the required number of signatures, the parliament often has to approve and sometimes the decision faces a court. For example, the 2016 Bulgarian referendum on changing the electoral system was initiated by a well-known showman. Initially, there were six questions on the ballot, the president referred to the Constitutional Court questioning the legality of three questions, and there were left only three.

The effects for controls (Fig. 1) indicate that slightly more referendums are called by both political elites and citizens on domestic policies when the government is more right-wing. The effect size is quite small and does not allow for a meaningful interpretation of the results. Our empirical observation for the referendums investigated in this article is that left-wing governments favored referendums on other topics. Quite often, this occurred in a context in which the domestic issues were settled and other elements, e.g., international affairs or post-materialist issues, became salient in society.

The absence of an external shock has a positive effect on calling referendums on domestic policies: the elites are two times more likely to call a referendum without an external shock, while citizens are 1.5 times more likely to follow the same avenue under the same circumstances. There are two possible explanations for this. First, the literature indicating the effect of external shock on policy change stems mainly from environmental studies, and popular votes on environmental issues are not part of domestic policies. Second, shocks require immediate action, while referendums are not the fastest tool for change. The process of its initiation, campaign and implementation takes longer than enacting legislations through other means, e.g., adoption in parliament or executive decree.

Conclusion

This article aimed to explain under what circumstances political elites and citizens call national level referendums on domestic policies in Europe. It tested the effect of four institutional variables that in theory is expected to be divergent for the two types of initiators. Some findings confirm the theoretical expectations and indicate that the experience with referendums and the democratic status of a country influence political elites and citizens in different directions. Other results confirm the theoretical expectations only for one of the two types of initiators. Longer time passed from referendums in a neighboring country explains the elite-initiated referendums on domestic policies. The coalition governments are also more prone to citizen-initiated referendums on domestic policies compared to single-party governments.

At the same time, the analysis indicates that there are some factors that have a similar effect on the two types of initiators. These are the existence of coalition governments and the longer time passed from a referendum on a similar policy in a neighboring country. To these, we can add the two controls, which go in the same direction for both initiators: right-wing governments and the absence of external shocks favor the referendums on domestic policies from political elites and citizens to a similar extent. These results form the basis for two broad observations. First, the institutions have an impact on the decision to call for a referendum on domestic policies. The composition of the government, the democratic status of the country and the previous use of referendums are important predictors. Equally important, referendums on domestic policies are often initiated in a quiet external environment in which a referendum-oriented behavior of the neighbors and shocks are not relevant. These point in the direction of referendums being called when the domestic situation requires a decision rather than copying or reacting to external factors. Second, in practice, the European political elites and citizens are driven by several common factors in their decisions to call for domestic policy referendums. In spite of a divergent logic in the initiation process, the same variables facilitate or impede the use of referendums, e.g., coalition governments.

These findings have broad relevance for the study of referendums. The theoretical implication of this analysis is that the setting of national institutions and what happens within the country can explain the use of referendums on domestic policies much better than external factors. This conclusion can be a good point of departure for future analyses that look at determinants of referendums in comparative or single-case studies. These results show that institutional learning, mimetism and reactive behavior are less important in explaining referendums compared to the composition of the government or adaptation to the rules of direct democracy. This provides solid grounds to include the latter into theoretical explanatory models. The methodological lesson of this analysis is the possibility to conduct cross-country and longitudinal studies if referendums are analyzed according to policy areas. Our focus on domestic policies allowed the inclusion of many policies that spread for more than two centuries in Europe. Empirically, we learned that there are differences between the political elites and citizens as initiators of referendums, but there are also things that bring them together. Such an observation contributes to the literature on referendums in two ways. First, it strengthens the idea that politicians and citizens have different stakes in referendums. Second, it narrows the areas in which discrepancies in the politicians and citizens’ approaches differ by indicating shared determinants for their actions.

The emphasis on these dynamics reveals two main avenues for further research. The unexpected findings for citizen-initiated referendum suggest that it is important to investigate the exact mechanisms behind their initiation. One way would be to disentangle the category of domestic policies and look into the patterns within each component (constitutional issues, electoral and political system, and interior policies), alternatively detailed case studies might shed light on so far unknown factors. There is also potential for wider research by expanding the analysis beyond the European continent and including further policies in the model, for instance, welfare or post-materialist issues.

Notes

The last referendum included in this dataset is the one in February 2019 in the Republic of Moldova.

Abrogative referendums are held on enacted laws, whereas rejective referendums – on passed but yet not in force laws.

We also control for other variables such as the binding character of the referendum, adoption of legislative provisions regarding referendums, turnout or outcome of previous referendums. None of these have a strong or statistically significant effect on the dependent variable. For reasons of parsimony, we report in the article the model with the two controls that have a higher effect.

Since legal provisions for referendums and initiatives vary considerably across countries, we would like to call attention to the fact that although the analysis includes a great variety of countries, these are all the countries that allow for a referendum or citizen-initiative in the first place.

We would like to highlight that our choice to focus on domestic policies and not on other three policy domains is driven by a combination of theoretical and empirical reasons. However, this does not translate into the view that some topics are more important / salient for a society that others.

For citizens, we use a logarithmic interpretation of the odds-ratio since its value is lower than 1.

References

Altman, D. 2011. Direct Democracy Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bäck, H., and J. Lindvall. 2015. Commitment Problems in Coalitions: A New Look at the Fiscal Policies of Multiparty Governments. Political Science Research and Method 3(1): 53–72.

Bergman, M. E. 2019. Rejecting Constitutional Reform in the 2016 Italian Referendum: Analysing the Effects of Perceived Discontent, Incumbent Performance and Referendum-Specific Factors. Contemporary Italian Politics 11(2): 177–191.

Björklund, T. 1982. The Demand for Referendum: When Does It Arise and when Does It Succeed? Scandinavian Political Studies 5(3): 237–260.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. 2000. California’s Experience with Direct Democracy. Parliamentary Affairs 53(4): 644–656.

Bowler, S., and T. Donovan. 2002. Do Voters Have a Cue? Television Advertisements as a Source of Information in Citizen-Initiated Referendum Campaigns. European Journal of Political Research 41(6): 777–793.

Budge, I., and H.-D. Klingemann. 2001. Finally! Comparative over-time mapping of party policy movement. In Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors and Governments: 1945–1998, ed. I. Budge, et al., 19–50. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butler, D., and A. Ranney, eds. 1978. Referendums : A Comparative Study of Practice and Theory. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Elkink, J. A., et al. 2017. Understanding the 2015 Marriage Referendum in Ireland: Context, Campaign, and Conservative Ireland. Irish Political Studies 32(3): 361–381.

Fischer, M. 2014. Coalition Structures and Policy Change in a Consensus Democracy. Policy Studies Journal 42(3): 344–366.

Gallagher, M. 1996. Conclusion. In The Referendum Experience in Europe, ed. M. Gallagher and P.V. Uleri, 226–252. Houndmills: MacMillan Press.

Gherghina, S. 2017. Direct Democracy and Subjective Regime Legitimacy in Europe. Democratization 24(4): 613–631.

Gherghina, S. 2019. How Political Parties Use Referendums: An Analytical Framework. East European Politics and Societies 33(3): 677–690.

Gordon, T.M. 2009. Bargaining in the Shadow of the Ballot Box: Causes and Consequences of Local Voter Initiatives. Public Choice 141(1–2): 31–48.

Grossman, P.Z. 2015. Energy Shocks, Crises and the Policy Process: A Review of Theory and Application. Energy Policy 77: 56–69.

Gunther, R., and L. Diamond. 2003. Species of Political Parties: A New Typology. Party Politics 9(2): 167–199.

Hobolt, S.B. 2009. Europe in Question. Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hug, S. 2004. Occurrence and Policy Consequences of Referendums. A Theoretical Model and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Theoretical Politics 16(3): 321–356.

Hug, S. 2005. The political effects of referendums: An analysis of institutional innovations in Eastern and Central Europe. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 38(4): 475–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2005.09.006.

Hug, S., and G. Tsebelis. 2002. Veto Players and Referendums Around the World. Journal of Theoretical Politics 14(4): 465–515.

Inglehart, R. 1989. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kaufmann, B., R. Büchi, and N. Braun. 2010. Guidebook to Direct Democracy in Switzerland and Beyond. 4th edn. Marburg: The Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe (IRI).

Keeler, J. T. 1993. Opening the Window for Reform Mandates, Crises, and Extraordinary Policy-Making. Comparative Political Studies 25(4): 433–486.

Kriesi, H. 2005. Direct Democratic Choice. The Swiss Experience. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

Laisney, M. 2012. The Initiation of Local Authority Referendums: Participatory Momentum or Political Tactics? The UK Case. Local Government Studies 38(5): 639–659.

Lijphart, A. 1984. Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-one Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Marxer, W., and Z.T. Pallinger. 2009. Stabilising or destabilising? Direct-democratic instruments in different political systems. In Referendums and Representative Democracy: Responsiveness, Accountability and Deliberation, ed. M. Setälä and T. Schiller, 34–55. London: Routledge.

Mendez, F., M. Mendez, and V. Triga. 2014. Referendums and the European Union: A Comparative Inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mooney, C.Z. 2001. Modeling Regional Effects on State Policy Diffusion. Political Research Quarterly 54(1): 103–124.

Morel, L. 2018. Types of referendums, provisions and practice at the national level worldwide. In The Routledge Handbook To Referendums And Direct Democracy, ed. L. Morel and M. Qvortrup, 27–59. London: Routledge.

Morel, L., and M. Qvortrup, eds. 2017. The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy. London: Routledge.

Nohrstedt, D., and C.M. Weible. 2010. ‘The Logic of Policy Change after Crisis: Proximity and Subsystem Interaction. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 1(2): 1–32.

Offe, C. 1991. Capitalism by Democratic Design? Democratic Theory Facing the Triple Transition in East Central Europe. Social Research 58(4): 865–881.

Papadopoulos, Y. 1995. Analysis of Functions and Dysfunctions of Direct Democracy: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Perspectives. Politics & Society 23(4): 421–448.

Papadopoulos, Y. 2001. How Does Direct Democracy Matter? The Impact of Referendum Votes on Politics and Policy-Making. West European Politics 24(2): 35–58.

Pétry, F., and D. Duval. 2018. Electoral Promises and Single Party Governments: The Role of Party Ideology and Budget Balance in Pledge Fulfillment. Canadian Journal of Political Science 51(4): 907–927.

Qvortrup, M. 2014a. Introduction: Theory, practice and history. In Referendums Around the World, ed. M. Qvortrup, 1–16. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Qvortrup, M. 2014b. Referendums Around the World. The Continued Growth of Direct Democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Qvortrup, M. 2017. Demystifying Direct Democracy. Journal of Democracy 28(3): 141–152.

Qvortrup, M. 2018. Direct democracy and referendums. In The Oxford handbook of electoral systems, ed. E.S. Herron, R.J. Pekkanen, and M.S. Shugart, 365–386. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rahat, G. 2009. Elite motives for initiating referendums: Avoidance, addition and contradiction. In Referendums and Representative Democracy Responsiveness, accountability and deliberation, ed. M. Setälä and T. Schiller, 98–116. London: Routledge.

Sabatier, P.A. 1987. Knowledge, Policy-Oriented Learning, and Policy Change: An Advocacy Coalition Framework. Science Communication 8(4): 649–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164025987008004005.

Sabatier, P.A. 1998. The advocacy coalition framework: Revisions and relevance for Europe. Journal of European Public Policy 5(1): 98–130.

Sartori, G. 1976. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saurugger, S., and F. Terpan. 2016. ‘Do Crises Lead to Policy Change? The Multiple Streams Framework and the European Union’s Economic Governance Instruments. Policy Sciences 49(1): 35–53.

Schiller. 2012. ‘Conclusions’. In Setälä, M., and Schiller, T. (Eds.), Referendums and Representative Democracy: Responsiveness, accountability and deliberation. London: Routledge, pp. 207–219.

Schiller, T., ed. 2011. Local Direct Democracy in Europe. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Serdült, U., and Y. Welp. 2012. Direct Democracy Upside Down. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 8(1): 69–92.

Setala, M., and T. Schiller, eds. 2012. Citizens’ Initiatives in Europe: Procedures and Consequences of Agenda-Setting by Citizens. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Silagadze, N., and S. Gherghina. 2020. Referendum Policies across Political Systems. The Political Quarterly 91(1): 182–191.

Smith, G. 1976. The Functional Properties of the Referendum. European Journal of Political Research 4(1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1976.tb00787.x.

Walker, M.C. 2003. The Strategic Use of Referendums: Power, Legitimacy, and Democracy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wen, J., et al. 2016. Does government ideology influence environmental performance? Evidence based on a new dataset. Economic Systems 40(2): 232–246.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gherghina, S., Silagadze, N. Calling referendums on domestic policies: how political elites and citizens differ. Comp Eur Polit 19, 642–661 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00252-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00252-7