Abstract

This study examines the effect of FDI openness to China and the rest of the world (ROW) on democracy levels of African countries in the short and long terms. We propose and test the hypothesis that the nexus between FDI openness and democracy is moderated by the grabbing and helping hands of regime corruption of African countries. We argue that in the short run, FDI openness will negatively impact democracy (grabbing hand) in corrupt regimes. However, in the long run there will be a positive effect (helping hand) as the revenue spillovers from the investment projects will reach the society empowering the middle class to demand better institutional qualities. We test these theories with a unique panel dataset spanning 2003–2017. Our dataset includes gravity model and politico-economic variables not only between China and African countries but also between the ROW. Building on examples from the existing research, we test the short-run impacts with dynamic GMM model (Blundell and Bond, J Econ, 87(1):115–143, 1998), whereas we test the long-run relationships with two stage least squares fixed effects models. To account for transaction costs and endogeneity problems, in the first stage we apply instruments on openness to both China and ROW FDI. We find statistically strong yet mixed results for our expectations. While in the short-run corrupt African countries that liberalize to Chinese FDI have lower democracy levels, in the long run, the FDI openness has a positive influence. Our results are robust to alternative measurements of democracy, 3- and 5-year non-overlapping smoothed averages and exclusion of top five countries with FDI openness to China and ROW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Li et al. (2018) for a detailed literature review on recent development in the area of research that explores the link between democratization and foreign investments.

For example, Li et al. (2018) provide a well-defined set of factors which can be summarized as 1) high audience costs in democracies for breaking contracts with foreign investors, 2) presence of veto-players to block expropriation of foreign investments, 3) checks and balances provide policy stability for foreign partners, 4) democracies present better opportunities for investments as individual and property rights are well protected which lowers the expropriation risks, 5) democracies have more media freedom, transparent election, and political stability than autocracies which enable foreign investors to hold violators of investment contracts accountable.

Yet, other works such as Bermeo (2016) find that in the post-Cold War reality, the investments from foreign donors rarely contributed to the institutional development of hybrid regimes that are plagued with corruption.

Borojo and Yushi (2020) use gravity models with PPML approach yet they analyze the reverse causation from institutional qualities and business environments in African countries on the extent of Chinese FDI flows. NguyenHuu and Schwiebert (2019) examine how the Chinese FDI to African countries impact poverty and income inequality.

Many country-level investment statistics reported by both African countries and their partners represent the flows of FDI, whereas in this study we are interested in the FDI stocks. Moreover, other sources like Bureau of Economic Analysis include information on US outward investments to African countries, yet, similar to European country reports from UNCTAD, the BEA also suffers from missing data on many country-year observations between 2003-2017 period.

Malikane and Chitambara (2017) also include interaction terms between FDI and democracy. Instead of democracy we interact FDI openness to China and ROW with regime corruption indices in African countries.

They rely on the inverse of geographic remoteness weighted by the size of the economy (GDP). as such, the formula for this instrument is: \(Z_{i} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{n} = \frac{1}{{dist_{i,j} }} \times GDP{\text{ per capita}}\)

Including similar variables such as inverse distance, bilateral WTO membership and landlocked for the ROW will introduce an overestimation bias in our models as more than 200 individual measures of each of these variables will need to be added to the regression for each country excluding China. To include only one measure per variable mentioned above for the ROW, we added the values for each variable among Africa’s top economic partners around the world and averaged those results for an African country i at time t. For example, the ROW WTO membership variable takes on the value of 1 if an African country shares partnership in the organization with at least three of top commercial partner countries and 0 otherwise.

We set this critical value to α = 0.05 which is also the default in the R package ’cragg’

The landlocked as an instrument is the same for both dependent variables. Our third instrument is a binary taking on a value of 1 when a given African country is jointly member of WTO with either China or any top partners included in the ROW. Following Aziz and Mishra (2016), Kim and Trumbore (2010), Fan et al. (2009) and Gossel (2018) we incorporate the log of trade openness (exports + imports / GDP) for each African country with the world (including China and all top commercial ROW partners) as our last instrument.

In the first order we expect to get a low p-value which establishes that there is no first order autocorrelation, while in the second order conditions we expect to obtain high p-values to establish the auto-correlation of first differenced equations.

When, for example, there is a common trending pattern between democracy index and FDI openness, the fixed effects or instrumental variable analysis could neglect accounting for a spurious relationship. Therefore, by looking into equilibrium level of democracy in each country, something that neither IV nor fixed effects permit to initiate, the GMM model considered here examines the short-run unit specific characteristics that could have some influence on the democracy levels in African countries.

Specifically, the GMM estimation is predicted by two datasets of the original panel, one in differences and one in levels (original values). The instruments that are specific for the differenced equation take upon the value of zero for the equation in levels, and contrarywise the level equation-based instruments have values of 1 and 0 for other equations.

We normalize the overspecification of instrumental variables in this model by enabling the collapse option in the pgmm function of plm R package. This allows to avoid the estimation bias resulted by increasing instrumental variable count. The collapse option restricts overfitting the endogenous variables in small samples. Using the collapse option also ensures that the number of GMM instruments does not exceed the number of countries in the observed sample.

We do not interpret those results since the intended use of the first stage models was to derive predicted probabilities for FDI openness to China and ROW by using gravity model instruments. Hence those are not of major significance for our hypothesis testing. We nonetheless report the regression results for the first stage gravity type models in the supplementary materials which are available online to preserve space in the main paper.

In the log-linear model, a one-unit change in X (X = 1) is associated with a (100 ×\(\beta\))% change in Y. In all our first stage models, we do not apply logarithmic transformation to the predicted levels of FDI openness to China or ROW. Additionally, the scale for Chinese and ROW FDI openness is the predicted value from the first stage. The predicted values can be negative or positive depending on the direction of the effect produced by the gravity model covariates.

7Note that we include the logarithmically transformed regime corruption in the interaction term, while the predicted FDI openness is in original levels. Hence, this makes the interpretation of the coefficient in the log–log model to be in terms of elasticity. In the log–log model, a 1% change in X is associated with a \(\beta_{i}\)% change in Y. Thus, in this specification \(\beta_{i}\) is the elasticity of democracy index with respect to the interaction term.

8The OLS model assumes that the residuals are distributed independently and identically which creates a problem when estimating country specific effects as those are completely ignored by the OLS model. The fixed effects approach for within country investigation allows to control for time-invariant unobserved individual characteristics that can be correlated with the observed independent variables.

As the literature informs, to make more robust inferences about the short-run relationship between economic activity variables and democracy levels of African countries we need to have sufficient variation in the cross sections and time-periods (Roodman, 2009; Blundell and Bond, 1998). Therefore, following Kucera and Principi (2014) we use the 3-year averages in order to maintain the requirement for the minimum size of time periods.

The dependent variable is composite democracy index that we constructed using the five indices of democracy from V-Dem.

The test specifications for Sargan (J-test), Wald test, AR(1) and AR(2) suggest that the exogenous and GMM specific instruments are not weak, that there is no overidentification, and no auto-correlation present in the estimated models, which validates the robustness of these results.

Borojo and Yushi (2020) treat Chinese investments to Africa as the outcome of interest, while Mourao (2018) used Chinese FDI as percentage of GDP in each African country as the dependent variable. Both of these studies include controls for institutional qualities, yet none performs empirical analysis to observe endogenous regime transitions.

References

Acemoglu, D. 2008. Oligarchic versus democratic societies. Journal of the European Economic Association 6(1): 1–44.

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, J.A. Robinson, and P. Yared. 2008. Income and democracy. American Economic Review 98(3): 808–842.

Acemoglu, D., S. Naidu, P. Restrepo, and J.A. Robinson. 2019. Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy 127(1): 47–100.

Acquah, A.M., and M. Ibrahim. 2020. Foreign direct investment, economic growth and financial sector development in Africa. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment 10(4): 315–334.

Adolph, C., V. Quince, and A. Prakash. 2017. The shanghai effect: Do exports to China affect labor practices in Africa? World Development 89: 1–18.

Alden, C., and C. Alves. 2008. History and identity in the construction of China’s Africa policy. Review of African Political Economy 35(115): 43–58.

Alence, R. 2004. Politicalinstitutionsanddevelopmentalgovernanceinsub-saharanafrica. Journal of Modern African Studies, pp. 163–187.

Amighini, A., and M. Sanfilippo. 2014. Impact of south–south fdi and trade on the export upgrading of African economies. World Development 64: 1–17.

Anderson, J.E., and E. Van Wincoop. 2003. Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review 93(1): 170–192.

Arellano, M., and S. Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58(2): 277–297.

Arezki, R., and T. Gylfason. 2013. Resource rents, democracy, corruption and conflict: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies 22(4): 552–569.

Asiedu, E., and D. Lien. 2011. Democracy, foreign direct investment and natural resources. Journal of International Economics 84(1): 99–111.

Ay, A., O. Kızılkaya, T. Akar, et al. 2016. The effects of corruption and democracy on fdi in developing countries: An empirical investigation. Business and Economics Research Journal 7(3): 73–88.

Aziz, O.G., and A.V. Mishra. 2016. Determinants of fdi inflows to Arab economies. The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development 25(3): 325–356.

Bailey, N. 2018. Exploring the relationship between institutional factors and fdi attractiveness: A metaanalytic review. International Business Review 27(1): 139–148.

Bak, D., and C. Moon. 2016. Foreign direct investment and authoritarian stability. Comparative Political Studies 49(14): 1998–2037.

Bellos, S., and T. Subasat. 2012a. Corruption and foreign direct investment: A panel gravity model approach. Bulletin of Economic Research 64(4): 565–574.

Bellos, S., and T. Subasat. 2012b. Governance and foreign direct investment: A panel gravity model approach. International Review of Applied Economics 26(3): 303–328.

Bermeo, S.B. 2016. Aid is not oil: Donor utility, heterogeneous aid, and the aid-democratization relationship. International Organization 70(1): 1–32.

Blundell, R., and S. Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87(1): 115–143.

Bodomo, A. (2009). Africa-China relations: Symmetry, soft power and south Africa. China Review, pp. 169– 178.

Bogliaccini, J.A., and P.J. Egan. 2017. Foreign direct investment and inequality in developing countries: Does sector matter? Economics and Politics 29(3): 209–236.

Borojo, D.G., and J. Yushi. 2020. The impacts of institutional quality and business environment on Chinese foreign direct investment flow to African countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 33(1): 26–45.

Bougharriou, N., Benayed, W., and Gabsi, F. B. 2019. The democracy and economic growth nexus: do fdi and government spending matter? evidence from the Arab world. Economics, 13(1).

Brautigam, D. 2015. Will Africa Feed China?. Oxford University Press.

Broich, T. 2017. Do authoritarian regimes receive more Chinese development finance than democratic ones? empirical evidence for Africa. China Economic Review 46: 180–207.

Busse, M., C. Erdogan, and H. Mühlen. 2016. China’s impact on Africa–the role of trade, fdi and aid. Kyklos 69(2): 228–262.

Busse, M., and C. Hefeker. 2007. Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy 23(2): 397–415.

CAIR. 2019. Data: Chinese investment in Africa. School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University.

Chen, W., D. Dollar, and H. Tang. 2018. Why is China investing in Africa? evidence from the firm level. The World Bank Economic Review 32(3): 610–632.

Cheung, Y.-L., P.R. Rau, and A. Stouraitis. 2010. Helping hand or grabbing hand? central vs local government shareholders in Chinese listed firms. Review of Finance 14(4): 669–694.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, M. S., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., et al. 2020. V-dem dataset v10.

Cragg, J.G., and S.G. Donald. 1993. Testing identifiability and specification in instrumental variable models. Econometric Theory 9(2): 222–240.

Culver, C. 2021. Chinese investment and corruption in Africa. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, pp. 1–27.

De Mesquita, B.B., and A. Smith. 2010. Leader survival, revolutions, and the nature of government finance. American Journal of Political Science 54(4): 936–950.

De Mesquita, B. B. and Smith, A. 2011. The dictator’s handbook: why bad behavior is almost always good politics. Public Affairs.

De Mesquita, B.B., A. Smith, R.M. Siverson, and J.D. Morrow. 2005. The logic of political survival. Cambridge: MIT press.

Dietrich, S. 2013. Bypass or engage? explaining donor delivery tactics in foreign aid allocation. International Studies Quarterly 57(4): 698–712.

Dinh, T.T.-H., D.H. Vo, T.C. Nguyen, et al. 2019. Foreign direct investment and economic growth in the short run and long run: Empirical evidence from developing countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12(4): 176.

Dorsch, M.T., F. McCann, and E.F. McGuirk. 2014. Democratic accountability, regulation and inward investment policy. Economics & Politics 26(2): 263–284.

Edoho, F.M. 2011. Globalization and marginalization of Africa: Contextualization of China-Africa relations. Africa Today 58(1): 103–124.

Egger, P., and H. Winner. 2005. Evidence on corruption as an incentive for foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy 21(4): 932–952.

Eisenman, J. 2012. China-Africa trade patterns: causes and consequences. Journal of Contemporary China 21(77): 793–810.

Fan, J.P., R. Morck, L.C. Xu, and B. Yeung. 2009. Institutions and foreign direct investment: China versus the rest of the world. World Development 37(4): 852–865.

Farazmand, H. and Moradi, M. 2014. Determinants of fdi: Does democracy matter? Journal of Law and Governance, 9(2).

Feng, Y. 1997. Democracy, political stability and economic growth. British Journal of Political Science, pp. 391–418.

Freckleton, M., A. Wright, and R. Craig Well. 2012. Economic growth, foreign direct investment and corruption in developed and developing countries. Journal of Economic Studies 39(6): 639–652.

Fredriksson, P.G., J.A. List, and D.L. Millimet. 2003. Bureaucratic corruption, environmental policy and inbound us fdi: theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics 87(7–8): 1407–1430.

Gastanaga, V.M., J.B. Nugent, and B. Pashamova. 1998. Host country reforms and fdi inflows: How much difference do they make? World Development 26(7): 1299–1314.

Goldsmith, A. A. 2021. Political regimes and foreign investment in poor countries: Insights from most similar African cases. European Journal of International Relations, p. 13540661211002903.

Gossel, S.J. 2018. Fdi, democracy and corruption in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Policy Modeling 40(4): 647–662.

Guerin, S.S., and S. Manzocchi. 2009. Political regime and fdi from advanced to emerging countries. Review of World Economics 145(1): 75–91.

Guha, S., N. Rahim, B. Panigrahi, and A.D. Ngo. 2020. Does corruption act as a deterrent to foreign direct investment in developing countries? Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies 11(1): 18–34.

Head, K., and T. Mayer. 2014. Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Handbook of international economics, vol. 4, 131–195. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Henri, N., N.N. Luc, and N. Larissa. 2019. The long-run and short-run effects of foreign direct investment on financial development in African countries. African Development Review 31(2): 216–229.

Huiping, C. 2013. Recent approaches in China’s bits and impact on African countries. In ASIL Annual Meeting Proceedings, vol. 107, pp. 228–230. JSTOR.

Humphrey, C., and K. Michaelowa. 2019. China in Africa: Competition for traditional development finance institutions? World Development 120: 15–28.

Jalil, A., A. Qureshi, and M. Feridun. 2016. Is corruption good or bad for fdi? empirical evidence from Asia, Africa and Latin America. Panoeconomicus 63(3): 259–271.

Kahouli, B., and S. Maktouf. 2015. The determinants of fdi and the impact of the economic crisis on the implementation of rtas: A static and dynamic gravity model. International Business Review 24(3): 518–529.

Kammas, P., and V. Sarantides. 2019. Do dictatorships redistribute more? Journal of Comparative Economics 47(1): 176–195.

Kathavate, J., and G. Mallik. 2012. The impact of the interaction between institutional quality and aid volatility on growth: theory and evidence. Economic Modelling 29(3): 716–724.

Kim, D.-H., and P.F. Trumbore. 2010. Transnational mergers and acquisitions: The impact of fdi on human rights, 1981–2006. Journal of Peace Research 47(6): 723–734.

Knutsen, C.H. 2011. Democracy, dictatorship and protection of property rights. The Journal of Development Studies 47(1): 164–182.

Knutsen, T., and A. Kotsadam. 2020. The political economy of aid allocation: Aid and incumbency at the local level in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 127: 104729.

Kolstad, I., and A. Wiig. 2011. Better the devil you know? Chinese foreign direct investment in Africa. Journal of African Business 12(1): 31–50.

Kucera, D.C., and M. Principi. 2014. Democracy and foreign direct investment at the industry level: evidence for us multinationals. Review of World Economics 150(3): 595–617.

Kurer, T., S. Häusermann, B. Wüest, and M. Enggist. 2019. Economic grievances and political protest. European Journal of Political Research 58(3): 866–892.

Lacroix, J., P.-G. Méon, and K. Sekkat. 2021. Democratic transitions can attract foreign direct investment: Effect, trajectories, and the role of political risk. Journal of Comparative Economics 49(2): 340–357.

Lee, H., G. Biglaiser, and J.L. Staats. 2014. The effects of political risk on different entry modes of foreign direct investment. International Interactions 40(5): 683–710.

Levchenko, A.A. 2007. Institutional quality and international trade. The Review of Economic Studies 74(3): 791–819.

Li, Q., E. Owen, and A. Mitchell. 2018. Why do democracies attract more or less foreign direct investment? a metaregression analysis. International Studies Quarterly 62(3): 494–504.

Li, Q., and A. Resnick. 2003. Reversal of fortunes: Democratic institutions and foreign direct investment inflows to developing countries. International Organization 57(1): 175–212.

López-Córdova, J.E., and C.M. Meissner. 2008. The impact of international trade on democracy: A long-run perspective. World Politics 60(4): 539–575.

Lynch, G., and G. Crawford. 2011. Democratization in Africa 1990–2010: an assessment. Democratization 18(2): 275–310.

Malikane, C., and P. Chitambara. 2017. Foreign direct investment, democracy and economic growth in southern Africa. African Development Review 29(1): 92–102.

Marquette, H., and C. Peiffer. 2018. Grappling with the “real politics” of systemic corruption: Theoretical debates versus “real-world” functions. Governance 31(3): 499–514.

Maruta, A.A., R. Banerjee, and T. Cavoli. 2020. Foreign aid, institutional quality and economic growth: Evidence from the developing world. Economic Modelling 89: 444–463.

Mathur, A., and K. Singh. 2013. Foreign direct investment, corruption and democracy. Applied Economics 45(8): 991–1002.

Meidan, M. 2006. China’s Africa policy: business now, politics later. Asian Perspective, pp. 69–93.

Moon, C. 2019. Political institutions and fdi inflows in autocratic countries. Democratization 26(7): 1256–1277.

Morrissey, O., and M. Udomkerdmongkol. 2012. Governance, private investment and foreign direct investment in developing countries. World Development 40(3): 437–445.

Mourao, P.R. 2018. What is China seeking from Africa? an analysis of the economic and political determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment based on stochastic frontier models. China Economic Review 48: 258–268.

NguyenHuu, T., and J. Schwiebert. 2019. China’s role in mitigating poverty and inequality in Africa: an empirical query. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 24(4): 645–669.

Pandya, S.S. 2014. Democratization and foreign direct investment liberalization, 1970–2000. International Studies Quarterly 58(3): 475–488.

Persson, T., and G. Tabellini. 2009. Democratic capital: The nexus of political and economic change. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1(2): 88–126.

Pinto, P.M., and B. Zhu. 2016. Fortune or evil? the effect of inward foreign direct investment on corruption. International Studies Quarterly 60(4): 693–705.

Quazi, R., V. Vemuri, and M. Soliman. 2014. Impact of corruption on foreign direct investment in Africa. International Business Research 7(4): 1.

Quazi, R.M. 2014. Corruption and foreign direct investment in east Asia and south Asia: An econometric study. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 4(2): 231.

Reiter, S.L., and H.K. Steensma. 2010. Human development and foreign direct investment in developing countries: the influence of fdi policy and corruption. World Development 38(12): 1678–1691.

Resnick, A.L. 2001. Investors, turbulence, and transition: Democratic transition and foreign direct investment in nineteen developing countries. International Interactions 27(4): 381–398.

Roodman, D. 2009. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system gmm in stata. The Stata Journal 9(1): 86–136.

Ross, A.G. 2019. Governance infrastructure and fdi flows in developing countries. Transnational Corporations Review 11(2): 109–119.

Sanfilippo, M. 2010. Chinese fdi to Africa: what is the nexus with foreign economic cooperation? African Development Review 22: 599–614.

Sautman, B. and Hairong, Y. 2009. African perspectives on China-Africa links. The China Quarterly, pp .728–759.

Sellner, R. 2019. Non-discriminatory trade policies in panel structural gravity models: Evidence from Monte Carlo simulations. Review of International Economics 27(3): 854–887.

Shan, S., Lin, Z., Li, Y., and Zeng, Y. 2018. Attracting Chinese fdi in Africa. Critical perspectives on international business.

Silva, J.S., and S. Tenreyro. 2006. The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and Statistics 88(4): 641–658.

Stock, J. H. and Yogo, M. 2002. Testing for weak instruments in linear iv regression.

Subasat, T., and S. Bellos. 2013. Governance and foreign direct investment in Latin America: A panel gravity model approach. Latin American Journal of Economics 50(1): 107–131.

Swedlund, H.J. 2017. Is China eroding the bargaining power of traditional donors in Africa? International Affairs 93(2): 389–408.

Talamo, G. 2007. Institutions, fdi, and the gravity model. In Workshop PRIN 2005 SU, Economic Growth; Institutional and Social Dynamics, pp .25–27.

UNCTAD. 2019. World investment report 2019: Special economic zones. UN.

Van Bergeijk, P.A., and S. Brakman. 2010. The gravity model in international trade: Advances and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whalley, J., and A. Weisbrod. 2012. The contribution of Chinese fdi to Africa’s pre crisis growth surge. Global Economy Journal 12(4): 1850271.

Yang, B. 2007. Autocracy, democracy, and fdi inflows to the developing countries. International Economic Journal 21(3): 419–439.

Zhu, B., and W. Shi. 2019. Greasing the wheels of commerce? corruption and foreign investment. The Journal of Politics 81(4): 1311–1327.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for their valuable comments which improved the paper significantly. The author would like to extend gratitude to Samantha Vortherms, Dan Bogart and Bernie Grofman for their constructive and very detailed comments on earlier drafts of this project. The author would also like to show appreciation to Sanjana Goswami, Stergios Skaperdas, Andrew Benson, Ines Levin, Steven Tarango, Amihai Glazer, Jeff Kopstein, David Meyer, Uras Demir, Sara McLaughlin Mitchell, Clayton Webb, Antonio Rodriguez-Lopez, Aria Golestani, Mark Hup, Kyle Kole, Fabrizio Marodin, Arpita Nepal and Avik Sanyal for motivating discussions and guidance provided throughout the process of finalizing this project. This research project was supported by Jack W. Peltason Center for the Study of Democracy and Center for Global Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of California-Irvine, as well as the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: Data

In this section, we discuss the conceptual descriptions of variables and their measurements and we also present descriptive statistics in Table 5. To preserve space, we present the results and discussions of the first-stage models for our main empirical estimations in the supplementary materials available online . In this section, we report the robustness check results using different indices of democracy, and 3- and 5-year averages of our key data frame.

Below are the definitions of the five democracy measures from the Varieties of Democracy version 10 that we use to construct the composite variable of democracy index used in our study. The scales for the five democracy indices from V-Dem dataset are coded based on expert survey responses. The scale ranges between 0 and 1.

Electoral Democracy

Question To what extent is the ideal of electoral democracy in its fullest sense achieved?

Clarification The electoral principle of democracy seeks to embody the core value of making rulers responsive to citizens, achieved through electoral competition for the electorate’s approval under circumstances when suffrage is extensive; political and civil society organizations can operate freely; elections are clean and not marred by fraud or systematic irregularities; and elections affect the composition of the chief executive of the country. In between elections, there is freedom of expression and an independent media capable of presenting alternative views on matters of political relevance. In the V-Dem conceptual scheme, electoral democracy is understood as an essential element of any other conception of representative democracy liberal, participatory, deliberative, egalitarian or some other.

Liberal Democracy

Question To what extent is the ideal of liberal democracy achieved?

Clarification The liberal principle of democracy emphasizes the importance of protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority. The liberal model takes a "negative" view of political power insofar as it judges the quality of democracy by the limits placed on government. This is achieved by constitutionally protected civil liberties, strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that, together, limit the exercise of executive power. To make this a measure of liberal democracy, the index also takes the level of electoral democracy into account.

Deliberative Democracy

Question To what extent is the ideal of deliberative democracy achieved?

Clarification: The deliberative principle of democracy focuses on the process by which decisions are reached in a polity. A deliberative process is one in which public reasoning focused on the common good motivates political decisions—as contrasted with emotional appeals, solidary attachments, parochial interests or coercion. According to this principle, democracy requires more than an aggregation of existing preferences. There should also be respectful dialogue at all levels—from preference formation to final decision—among informed and competent participants who are open to persuasion. To make it a measure of not only the deliberative principle but also of democracy, the index also takes the level of electoral democracy into account.

Participatory Democracy

Question To what extent is the ideal of participatory democracy achieved?

Clarification The participatory principle of democracy emphasizes active participation by citizens in all political processes, electoral and non-electoral. It is motivated by uneasiness about a bedrock practice of electoral democracy: delegating authority to representatives. Thus, direct rule by citizens is preferred, wherever practicable. This model of democracy thus takes suffrage for granted, emphasizing engagement in civil society organizations, direct democracy and subnational elected bodies. To make it a measure of participatory democracy, the index also takes the level of electoral democracy into account.

Deliberative Democracy

Question To what extent is the ideal of egalitarian democracy achieved?

Clarification The egalitarian principle of democracy holds that material and immaterial inequalities inhibit the exercise of formal rights and liberties and diminish the ability of citizens from all social groups to participate. Egalitarian democracy is achieved when 1 rights and freedoms of individuals are protected equally across all social groups; and 2 resources are distributed equally across all social groups; 3 groups and individuals enjoy equal access to power. To make it a measure of egalitarian democracy, the index also takes the level of electoral democracy into account.

The Freedom House

Civil liberties Civil liberties allow for the freedoms of expression and belief, associational and organizational rights, rule of law and personal autonomy without interference from the state. The more specific list of rights considered varies over the years. Political rights: Political rights enable people to participate freely in the political process, including the right to vote freely for distinct alternatives in legitimate elections, compete for public office, join political parties and organizations and elect representatives who have a decisive impact on public policies and are accountable to the electorate. The specific list of rights considered varies over the years.

Political rights Political rights enable people to participate freely in the political process, including the right to vote freely for distinct alternatives in legitimate elections, compete for public office, join political parties and organizations and elect representatives who have a decisive impact on public policies and are accountable to the electorate. The specific list of rights considered varies over the years.

World Bank Governance Indicators

Rule of Law “Rule of Law” includes several indicators which measure the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society. These include perceptions of the incidence of crime, the effectiveness and predictability of the judiciary and the enforceability of contracts. Together, these indicators measure the success of a society in developing an environment in which fair and predictable rules form the basis for economic and social interactions and the extent to which property rights are protected.

Voice and Accountability “Voice and Accountability” includes a number of indicators measuring various aspects of the political process, civil liberties and political rights. These indicators measure the extent to which citizens of a country are able to participate in the selection of governments. This category also includes indicators measuring the independence of the media, which serves an important role in monitoring those in authority and holding them accountable for their actions.

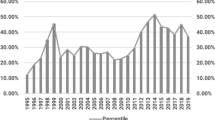

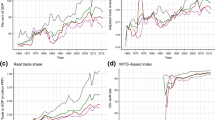

See Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

Appendix B: Methodology

Theoretical Underpinnings of the Gravity Model

In simplest form, the gravity model is motivated by Newton’s formula of gravity which estimates bilateral interaction between two countries with the ratio of economic size and distance (Sellner, 2019). The economic size is scaled as GDP of exporter/investor and importer/recipient countries. The model takes the following form:

where F is the FDI flow from country i to j, G is the GDP of economic partners, the denominator D indicates the distance between them, and C is a constant term. The logic of this model implies that larger countries with more wealthier economies will engage in commercial activities more than emerging economies (Head and Mayer 2014). Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) elaborate on the standard gravity equation by modifying it to control for the transaction costs of trade or FDI. They show that the relative trade/FDI costs directly influence the bilateral expenditures. Those relative costs are determined by country j's inclination to import from country i and vice versa based on multilateral resistance among the partners.

where F is the FDI flow revenue, W is the total GDP of all N countries in the world/dataset, G is the GDP of economic partners, \(y_{ij}\) is the cost exporter/investor, j incurs from importing/receiving from country i, \(\alpha > 1\) is the substitution elasticity term, \(E_{i}\) and \(L_{j}\) are the multilateral resistance terms for exporter/investor j and importer/recipient i indicating the flexibility of market access outwardly for i and inwardly for j, and \(\omega_{ij}\) is the disturbance error term.

The traditional econometric practice has been to linearize the multiplicative form of the gravity model by log transforming both sides of the equation (Santos Silva and Tenreyro, 2006). Performing linear log on Eq. (2) derives:

where previous assumptions on G, y, E, L and \(\omega_{ij}\) apply in addition to \(\beta_{0}\) denoting the constant term and other \(\beta_{i} ^{\prime}s\) representing the coefficient parameters of interest to be estimated with \(\beta_{3} = \left( {1 - \alpha } \right)\). After linearizing Eq. (5), Eq. (6) allows to log transform both sides of the equation (except the dummy variables) to estimate the elasticities between FDI openness and a vector of control variables that will account for transaction costs and unobserved endogeneity issues in the second-stage regression.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karavardanyan, S. Short-Term Harm, Long-Term Prosperity? Democracy, Corruption and Foreign Direct Investments in Sino-African Economic Relations. Comp Econ Stud 64, 417–486 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-021-00176-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-021-00176-x