Abstract

This paper compares the US long-run macroeconomic effects of foreign direct investment from Japan (1970–1990) with foreign portfolio investment from China (2000–2018). Investment from the both countries lowers the US inflation rate, and the effect from Japan is stronger than that from China. While Japan’s investment in the 1970–1990 period accounts for 88% of the unemployment-reducing effect of the overall US financial account surplus, China’s investment in the 2000–2018 period explains 65% of the unemployment-deterioration effect as well as 96% of the inflation-reducing effect of the overall US financial account surplus. The US inflation and unemployment impulse responses exhibit the pertinent supportive evidence. Furthermore, in contrast to Japan’s direct investment, China’s portfolio investment is more sensitive to dollar depreciation, higher inflation rate and lower real interest rate in the USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Japan won the status of the second largest economy in 1968, while China did so in 2010.

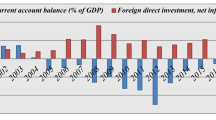

Our dataset indicates that the US bilateral trade-in-goods deficit with respect to Japan accounts for 95–118% of its bilateral current account deficit from 1976 to 1990; and its counterpart with respect to China is 86–104% from 2000 to 2016.

The balance in the primary income account is the amount by which US factor income payment such as interest payment to China for Chinese portfolio investment exceeds US factor income receipts from China. In contrast, the portion of net unilateral transfer (secondary income) in the US bilateral current account with China is very small.

As far as Japan’s foreign direct investment in the USA is concerned, “Japan supplied 44 percent of new plant investments in the USA during the period. Limiting Japanese FDI activity could slow technological advances in US manufacturing” (Ray 1991).

According to Schwarzenberg (2019), by the end of June of 2018, China’s holdings of US treasury debt and agency debt account for 86% of its entire portfolio investment in the USA. Also, see Setser (2008) for a discussion of the composition of China’s foreign assets, and the website of China State Administration of Foreign Exchange for the data of China’s foreign portfolio investment in specific countries, particularly in the USA.

The renminbi depreciation vis-à-vis the US dollar since 2013 (as shown in Panel B of Fig. 1) was partly related to capital outflow from China, including the exit of carry trade that used the dollar as a funding currency to invest in high-yielding assets in China before.

Here, the output gap is defined by \(\beta \left( {{\text{u}} - u_{n} } \right)\) using the Okun’s law. See Jones (2017) for reference.

In the context of this paper, e is defined as either units of Chinese renminbi per dollar (i.e., the RMB-Dollar exchange rate) or units of Japanese yen per dollar (Yen-Dollar exchange rate).

In this paper, the interest rates in the rest of the world are exogenous and thus treated as pre-determined; for simplicity, they are abstracted away from our model. Only the US interest rate appears in the US financial outflow (FO) and foreign portfolio inflow (FPI).

For simplicity, we have abstracted away the difference between the monetary authority’s policy rate and the private sector’s borrowing rate since the risk premium is not the focus in this paper.

“US automakers have made significant strides in manufacturing and product development performance as Japanese transplants have increased their presence in recent years. The same appears to be true for other US manufacturing industries, such as steel, machine tools, and tires.” (National Research Council 1998) Based on Ray (1991), Japan was the largest single-country source of investment in all FDI new plants and plant expansions in the USA for the 1979–1987 period, with its sum of the top 10 industry shares of all FDI and manufacturing FDI activity being 46.90 percent and 65.88 percent, respectively.

The disinflation effect of inward FDI holds as long as the supply-side source (an increase in the US TFP, say) has a greater marginal impact on FDI than the demand-side source (a decrease in the US unemployment, say), i.e., \(FDI_{T}^{'} > \left| {FDI_{u}^{'} } \right|\).

Here, the demand-side reactions refer to the composite effects of the interest-rate sensitivities of net financial outflow and domestic investment, the inflation responsiveness to the unemployment gap, and the overall monetary policy responses, as shown in the side condition for (7).

See Bernanke (2005).

See Harris (1995) for the stationary and non-stationary series and cointegration analysis.

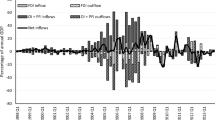

The both figures are based on impulse responses to Cholesky one standard deviation (with degree of freedom adjusted) innovation with 95% confidence interval using standard percentile bootstrap with 999 bootstrap replications.

The sign reversal for the unemployment impulse response to the dollar exchange rate is directly related to the exchange rate influence on foreign direct investment. The change in the exchange rate impact on unemployment suggests that the dollar depreciation lowers the cost of American physical assets to be acquired and therefore attracts more of Japan’s foreign direct investment in the short run but may also raise the operation cost of foreign direct investment afterwards and thus lower the return on these assets, therefore adversely affecting the initial momentum of favorable employment effects in the capital recipient countries. See Blonigen (2005).

References

Belke, A., and U. Volz. 2020. The yen exchange rate and hollowing out of the Japanese industry. Open Economies Review 31(1): 371–406.

Bernanke, BS. 2005. The global saving glut and the US current account deficit. Speech delivered at the Sandridge Lecture, Virginia Association of Economists, Richmond, VA., March 10, 2005.

Blonigen, B.A. 1997. Firm-specific assets and the link between exchange rates and foreign direct investment. American Economic Review 87(3): 447–465.

Blonigen, B.A. 2005. A review of the empirical literature on FDI determinants. Atlantic Economic Journal 33(4): 383–403.

De Mello, L. 1999. Foreign direct investment-led growth: Evidence from time series and panel data. Oxford Economic Papers 51(1): 133–151.

Borensztein, E., J.D. Gregorio, and J.W. Lee. 1998. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics 45(1998): 115–135.

Choucri, N., and R.C. North. 1975. Nations in conflict: National growth and international violence. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Corbett, J and Ito, T. 2010: What should the US and China learn from the past US-Japan conflict?” VoxEU/CEPR, April 30, 2010.

Ferguson, N., and M. Schularick. 2007. “Chimerica” and the global asset market boom. International Finance 10(3): 215–239.

Forbes, K.J. 2004: The United States, China and Japan: economic prospects and the role of foreign direct investment. Remarks to the Japan Society in New York City.

Harris, R. 1995. Using cointegration analysis in econometric modelling. Prentice Hall-Harvester Wheatsheaf: London and New York.

Hsieh, D. 1982. The determination of the real exchange rate: the productivity approach. Journal of International Economics 12(2): 355–362.

Ito, H. 2009. US current account debate with Japan then, with China now. Journal of Asian Economics 20(3): 294–313.

Jones, C.I. 2017. Macroeconomics. W.W. Norton and Company: New York and London.

Keohane, R.O. 2002. Power and governance in a partially globalized world. London and New York: Routledge.

Komiya, R., and R. Wakasugi. 1991. Japan’s foreign direct investment. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 513, Japan's external economic relations: Japanese perspectives (1991): 48–61.

Lu, F. 2006. The research on China’s “double surplus” of international balance of payments: a theoretical thinking of China’s trillions of dollars of foreign exchange reserves. The Journal of World Economy 11: 3–10.

Marston, R.C. 1986. Real exchange rates and productivity growth in the United States and Japan. In NBER Working Papers 1922.

Moran, T.H., and L. Oldenski. 2015. Japanese investment in the United States: superior performance, increasing integration. Policy Brief 15-3. Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington, DC.

National Research Council. 1998. Foreign direct investment and the US-Japan economic and technological relationship. In: Global Economy, Global Technology, Global Corporations, Reports of a joint task force of the National Research Council and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science on the Rights and Responsibilities of Multinational Corporations in an age of technological interdependence, Chapter 3. The National Academic Press: Washington, DC.

Ray, E.J. 1991. A profile of recent foreign investment in the US The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 516, Foreign investment in the United States (Jul., 1991): 50-65. Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Rosen, D.H. and H. Thilo. 2013. The changing US-China investment relationship. In EABER working paper series 23750.

Schwarzenberg, A.B. 2019. US-China investment ties: overview and issues for congress. In Focus, Congressional Research Service.

Setser, B. 2008. Comment: impact of China investment corporation on the management of China’s foreign assets. In Morris G and Lardy, NR (eds). Debating China’s Exchange Rate Policy, Chapter 5. Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington DC.

Summers, L.H. 2016. The age of secular stagnation- what it is what to do about it. Foreign Affairs, March/April 2016.

Wang, P.M., J. Alba, and D.H. Park. 2013. Determinants of different modes of FDI: firm-level evidence from Japanese FDI into the US. Open Economies Review 24(3): 425–446.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees for their helpful constructive comments and suggestions on a previous draft of this paper, and Nauro F. Campos (Editor of Comparative Economic Studies) for the encouragement in the review process. The authors are also grateful to Calla Wiemer for the thoughtful comments on the paper in its earlier stage. Any errors or omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Comparative Static Analysis

Appendix: Comparative Static Analysis

Totally differentiating Eq. (1) produces the following expression:

where \(NCO_{e}^{'} = FO_{e}^{'} - \left( {1 - I_{{FDI}}^{'} } \right)FDI_{e}^{'} - FPI_{e}^{'} > < 0,~as~(FO_{e}^{'} - FPI_{e}^{'} ) > < \left( {1 - I_{{FDI}}^{'} } \right)FDI_{e}^{'} .\) In (2), three endogenous variables (inflation rate \(\pi\), unemployment rate u, and real interest rate r) are the major macroeconomic indicators for the USA, and they are dependent on three pre-determined variables in the USA (safe-haven status S, total factor productivity T, and the dollar exchange rate e) that influence financial inflow into the USA. Although the Japanese FDI’s crowd-in effect is significant enough, such a crowd-in effect is assumed to be bounded as follows:

Thus, the Jacobian determinant for the endogenous variables is positive

Solving (2) for nine comparative-static derivatives (each of the three endogenous variables with respect to three external exogenous economic shocks) produces the following results:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Deng, X. Macroeconomic Impacts of the US External Imbalances with Two Large Emerging Asian Economies: Japan (1970–1990) versus China (2000–2018). Comp Econ Stud 64, 255–279 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-021-00158-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-021-00158-z

Keywords

- Current account deficit

- Emerging economy

- Foreign direct investment

- Foreign portfolio investment

- Inflation

- Unemployment