Abstract

In Denmark, as in many other countries, declining fertility rates have stimulated debates about ‘underpopulation’ as a threat to the nation’s future sustainability. At the same time, climate change has initiated debates about ‘overpopulation’ and ‘overconsumption’ as a problem for sustaining the planet. While both debates can be understood in terms of demographic anxieties placing sustainable reproductive futures’ central, they exhibit different ideas of what ‘sustainable’ entails. In this article, we analyze how sustainable reproduction is negotiated within agendas of respectively a national fertility crisis and the climate crisis. We do so by mapping the media debates in Denmark in the period between 2010 and 2022. The aim of the article is to contribute to an understanding of the repro-paradox which simultaneously calls upon young Danes to reproduce more and less.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“No help to the childless: we will be short on children” (Politiken, 26 May 2010)

“Low birth rates are good for the climate” (Politiken, 18 April 2013)

“Want to do something for the climate? Have fewer children” (dr.dk, 2 June 2018)

“Poor sperm, women under pressure and lonely men. The problem is not overpopulation, its underpopulation” (Politiken, 23 February 2020)

“Plan B: Childless in the name of the climate” (Weekendavisen, 12 November 2021)

Over the past decade, headlines like the ones above have collided in Danish media, creating what we in this article identify as a repro-paradox. On the one hand, a scenario of ‘underpopulation’ has been fueled by Danish fertility specialists who are ringing the alarm about the ‘epidemic nature’ of infertility and the lack of ‘fertility awareness’ among the Danes, which challenges the sustainability of the welfare state. On the other, the climate crisis has triggered debates about ‘overpopulation’ positioning population decrease as central in ensuring a sustainable planetary future. Here, calling in the ‘overconsuming’ people of the Global North, reproductive decisions are linked to the individual ‘carbon footprint’ but also to concerns about the future of (unborn) children in a time of climate crisis.

In this article, we aim to advance an understanding of the two reproductive agendas. We argue that they create a tension—what we call a repro-paradox—in their calls for sustainable reproduction, addressing young Danes’ reproductive futures. We find that during the last decade, this tension has intensified in Danish mainstream media with each side of the debate pinpointing the importance of pursuing sustainable reproduction but also with very different visions of what sustainability in this relation entails.

The mobilization of ‘demographic anxieties,’ such as ‘overpopulation’ and ‘underpopulation,’ is not a new phenomenon. As feminist scholars have long discussed, worries about the size of the population have shaped the formation of the modern nation state and materialized in a vast variety of biopolitical commitments seeking to control both numbers and ‘quality’ (Yuval-Davis 1997; Hartmann 2016; Franklin 2022). Currently, a renewed interest has occurred in feminist scholarship to critically engage with the notion of population and the ways in which demographic fears and figures are mobilized in various contexts (Dow and Lamoreaux 2020; Hendrixsson et al. 2020; Zordo et al. 2022). A growing number of studies address how pronatalist policies have resurfaced in both Asia and Europe in response to the scenario of ‘ultra-low fertility’ (Huang and Wu 2018; Hendrixsson et al. 2020; Whittaker 2022; Zordo et al. 2022). And fueled by Donna Haraway’s (2016) provocative call to “make kin, not babies,” another body of literature has begun to discuss reproductive politics considering the climate crisis (Ojeda et al. 2019; Schultz 2021; Meynell, et al. 2023; Sasser 2024). While Clarke and Haraway (2018) call for a feminist response to mitigate climate collapse of an overpopulated planet, other scholars have critically warned against the adoption of neo-Malthusian rhetoric and its ‘too many’ logics especially due to how it places moral and discursive, if not practical, restrains on reproductive freedom (Dow and Lamoreaux 2020; Hendrixson et al. 2020; Sasser 2024).

Like in the Danish public debate, the scholarly work tends to zoom in on one side of the problem, directing the focus to either the agenda of ‘overpopulation’ or ‘underpopulation’ with little acknowledgment of their paradoxical coexistence (see Hendrixsson et al. 2020; Homanen and Meskus 2023 for exceptions). To fill this gap, the aim of this article is to pursue this repro-paradox in the Danish reproductive landscape. We do so by investigating the discursive meaning-making within each of the two agendas as they unfold Danish mainstream media between 2010 and 2022. In the analysis, we center the notion of sustainable reproduction, exploring the formation of a discourse of a national fertility crisis emphasizing the need for more children and a discourse of a global climate crisis calling for fewer children. Drawing on the methodology of situational analysis (Clarke et al. 2018), our aim is not only to show the contradictory existence of these two agendas. We also attend to the complexities within each agenda to show how the arguments shift over time and that both agendas come to individualize the population problem.

Analyzing debates in the mainstream media is a way to acknowledge the media’s important role as part of “the narrative machinery” of our societies (Clarke et al. 2018, p. 51). Exploring how meaning is stabilized and destabilized over time and in relation to respectively national and global frameworks, we argue that the repro-paradox is crucial to figure out as it constitutes a context where young people are simultaneously called on to have fewer and more children. As our focus is on the repro-paradox between too many and too few, it is beyond the scope of the article to map extended debates about labor shortage, aging societies, and immigration policies which we therefore only briefly touch upon.

The article starts out with theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches, followed by two analytical sections which delineates first the evolvement of an agenda of (in)fertility crisis and secondly how the climate crisis gets linked to reproduction in the envisioning of a sustainable planetary future. We conclude with a discussion of the repro-paradox and how both agendas transfer responsibility for sustainable reproduction to the individual.

Framing demographic anxieties and the dilemma of sustainable reproduction

Our analysis is situated in the growing body of scholarship on ‘demographic anxieties’ (Krause 2001; Zordo et al. 2022). We use this term as an analytical lens through which we explore how specific reproductive concerns emerge and develop in the Danish context. Initially coined through research on declining fertility rates in Italy (Krause 2001), the term has since been broadened to include reproductive policies that target specific populations as well as reproductive inequalities between groups of individuals within and across the Global North and Global South (Krause and De Zordo 2012; Davis 2019). Similar terminology has also proved useful in work studying the shifts away from concerns about overpopulation to worries about declining populations, especially in Southeast Asia (Huang and Wu 2018; Huang 2022; Whittaker 2022). While demography centers the calculation of populations, our use of demographic anxieties as a framework refers to the problem-making based on these calculations and in particular the interpretation of their predicted consequences. Situated in time, place, and context, demographic anxieties can thus be understood and analyzed as discursive constructions of certain population problems more than as facts about troubling numbers of population (Franklin 2022).

While population control has long been the subject of much feminist research, both climate change and scenarios of ‘ultra-low fertility’ have spurred new critical debates about the relationship between demographic imaginaries and reproductive politics (Haraway 2016; Sasser 2017; Clarke 2018; Dow and Lamoreaux 2020; Hendrixson et al. 2020; Whittaker 2022). Bhatia et al. (2020) have raised concerns about the commonsense of a neo-Malthusian logic built into much of contemporary climate change scholarship and activism. This concern includes feminist work such as Haraway’s (2016, 2018), in which “growing human numbers are always a harbinger of impending environmental degradation” (Bhatia et al. 2020, p. 336; see also Meynell et al. 2023; Sasser 2017). Dow and Lamoreaux (2020) further critique how the move toward “non-natalism” produces “unnecessary and disproportionately distributed constraints on reproductive freedoms and bodily sovereignty” (Dow and Lamoreaux 2020, p. 476). A similar critique is advanced by Sasser (2017) in the concept of sexual stewardship which denotes how women's reproduction is woven into problematizations of overpopulation as a climate problem. Departing in the Global South, the sexual steward is one who responsibly manage her reproduction in ways that serve the common good. In this article, we place the concept in the Global North, seeing how the media serves as an important site for the production of sexual stewardship through the (re)production of reproductive imaginaries more broadly, and the mobilization of demographic anxieties in particular.

Another vein of literature on demographic anxieties is concerned with the advancement of pronatalist responses to scenarios of low and not least ultra-low fertility as it materializes in Southeast Asia (Huang and Wu 2018; Whittaker 2022) and, increasingly also in European countries, such as Spain (Pérez-Caramés 2017) or Norway (Kristensen 2020). Centering the ambivalences in reproductive politics, Huang (2022) develops the term ‘ambi-natalism’ to capture the current situation where the Chinese state abandoned the one-child policy for a pronatalist encouragement to have first two, then three children, but without any supportive measures to encourage the population to reproduce more. Huang’s work on IVF in China addresses not only the importance of analyzing the situatedness of pronatalism as it plays out in specific contexts, but also calls attention to the complexities of how biopolitical geographies translate to the individual level.

In sum, these bodies of literature show how discussions on reproduction are multi-leveled, complex, and ambivalent (Almeling 2015). In our analysis of the reproductive problem-making in Danish media debates, we wish to show how the various complexities and ambivalences are produced through certain (dis)locations between global and national as well as collective and individual orientations.

Methods and data

Our analysis builds on the mapping of mainstream media discourse, drawing on the methodology of situational analysis (SA), an explorative qualitative mapping technique well-suited to explore discursive formations and their production across a large set of data and over time (Clarke et al. 2018). Two searches were conducted in the media database Infomedia which contains content from Danish national, regional, and local newspapers, mainstream magazines, the national television, and radio as well as selected web sources (primarily those of the same newspapers, magazines, and the national television/radio).

One search had a specific focus on the linking of climate and reproduction though key words, such as ‘birthstrike,’ ‘having children climate crisis,’ ‘overpopulation children climate,’ identifying 82 articles in total. These keywords generated no hits in the first two years of the search period, indicating that the specific debate we are investigating is relatively new. The other search focused on tracking links between a fertility crisis and the advancement of a fertility awareness agenda. This search was based on key words around fertility and fecundity crisis as well as on the names of fertility experts who over the years have been active participant in the public debate about (in)fertility. We also searched for discussions of specific event such as the internationally discussed fertility awareness campaign ‘have you counted your eggs today?’ from Municipality of Copenhagen in 2015. As other participants showed up in the debate, we did additional searches adding more articles to the archive, which in total ended up comprising around 400 articles, including 21 opinion pieces written by fertility specialists addressing low fertility. The search period time frame of 2010–2022 was defined as to include a debate about the introduction of user fees on public assisted reproduction, which in 2010 highlighted low fertility as problematic.

In SA, extant discourse material is seen as a type of “claims-making device” (Clarke et al. 2018, p. 223) providing important insights into the processes of meaning-making in particular social worlds. In SA, the purpose is not only to analyze the content of discourse materials, but also to include and explore their situatedness, the how and why of discourse production (Clarke et al. 2018, p. 242). This means asking analytical questions such as “who cares and what do they want to do about it?” (Clarke et al. 2018, p. 72). Another central aim of this approach is to identify ‘arenas of concern’ in all their complexity. Following this approach, our searches have been inclusive to both journalistic pieces and opinion pieces.

Methodically, SA is performed through several rounds of explorative mappings. In situational maps, we noted the discursive constructions found in our material as well as the many agents (human and non-human, individual and collective). From here, we explored the relationships between the various elements in social arena maps and positional maps which elucidated the tensions and paradoxes of the debates as well as the dislocations between global and national perspectives, collective and individual commitments (Clarke et al. 2018, p. 253).

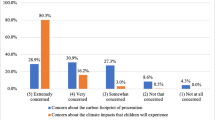

The positional map below summaries the positions within the two debates and shows the complexities within each agenda (Fig. 1).

In the following, we analyze each of the two crises individually to delineate how each agenda develops over time and how sustainable reproduction is negotiated, beginning with the agenda of (in)fertility awareness and ‘underpopulation.’

The (in)fertility crisis: low fertility as a threat to the sustainability of the welfare state

During the search period, an extensive number of articles have been written on the topic of infertility, both reporting on the high number of fertility treatments in Denmark published every year by the Danish health authorities and on the personal distress experienced by those who as involuntary childless undergo infertility treatment. While the later stories clearly contribute to the discursive project of depicting infertility as large-scale phenomenon with traumatic consequences at the individual level, in the following, we focus on the biomedical project of constructing (low) fertility as a societal problem. We do so through three subsections that delineate the how the crisis discourse has evolved over time.

Artificial insemination sustains the population

In 2010, the introduction of user fees on public fertility treatment as part of an economic reform following the fiscal crisis in 2008 (‘The Restoration Package’ 2010) triggers a discussion of a lurking fertility crisis. In a series of op-eds and news stories, medical professionals, employed in public fertility clinics, warn of the consequences of limiting access to publicly funded assisted reproduction. In their writings, they not only highlight the individual tragedies that will follow from limiting access to fertility treatment, but also stress the impact on the Danish birth rate:

Currently in Denmark, only 1.8 children are born per woman. This number is not high enough to uphold the population. Artificial conception and other infertility treatments have, in recent years, contributed to eight percent of all children born in Denmark. That is in every ordinary classroom, two children have been born following infertility treatment (...) By excluding many couples from the option to have a child, the birth rate will drop additionally.

(“Austerity measures: government fails the childless”, Politiken 30 May 2010)

As the quote illustrates, demographic data, and especially the idea of a replacement rate, are used not only to install fertility treatment as highly effective, but also to position low fertility as a problem. User fees reflect a political ignorance of the problem of infertility in Danish society, another op-ed argues (“Low birthrate: infertility—a massive societal problem”, Politiken, 17 June 2010). Infertility has become “epidemic,” this andrologist notes, with a particular reference to the significant drop in sperm quality in men across the industrialized countries. This “sperm crisis,” he argues several times during the search period, should be taken as seriously as the climate crisis. Drawing on experiences in Germany, the fertility doctors conclude that the fee, while implemented to save money, will be “a bad bargain” (e.g., “The worst bargain” in Berlingske, 19 September 2010). Referring to demographic projections made by the European Council in 2007, the fertility experts also suggest that the fee is “completely out of step with the labor shortage expected in the next decades” (“Out of touch with reality,” Jyllandsposten, 13 June 2010).

Important to the discursive formation of fertility crisis is the entanglement in biomedical logics. While the doctors define labor shortage as the consequence, latching on to an existing demographic anxiety of ‘the older burden’ of the aging Danish society, they locate the solution in attending to biological reproductive capacity. The doctors contend that one reason why infertility is not taken seriously is that it is not properly understood as a “disease of the reproductive organs” (e.g., “Out of touch with reality,” Jyllandsposten, 13 June 2010). This implies that infertility should not be treated neither as “self-imposed” nor a “condition of life,” as fertility specialists reiterate in a thematic section about the advancement of ART in Medical Weekly (“Artificial insemination keeps the population stabile,” 8 October 2012). Positioning infertility as a “folk disease,” they argue that this medical condition should be taken as seriously as other common chronic diseases falling within this classification such as diabetes, osteoporosis, or cardiovascular diseases. As a medico-statistical construct, the notion of folk disease locates infertility as “the most common chronic disease” based on estimations that between 15 and 25% of Danes in the reproductive age group experience infertility, when defined by the World Health Organization’s definition of not having conceived after 12 months of regular intercourse.

The construction of infertility as a folk disease not only highlights the need to provide free treatment within the Danish healthcare system, but it also positions infertility as a condition in need of prevention. This is another nodal point in the debate in the following years where ‘fertility awareness’ is put on the agenda.

Do it for Denmark: sperm checks and egg counting

In the following years, the prevention debate intensifies. Yet, the discourse of infertility crisis as a health crisis is expanded by growing attention toward reproductive aging. From 2012 we see many articles focusing on “extreme ignorance” about fertility among Danes who “know too little about reproductive deadlines” (“The Danes know too little about reproductive deadline”, dr.dk, 28 October 2014). This states that when Danes “begin on family building, biology is already severely declined” (“Fertility doctor: When we begin on family building, our biology is already severely declined”, Jyllandsposten, 21 November 2014). Evoking the cultural imaginary of the ticking biological clock, reproductive delay becomes a central component in making the (in)fertility crisis a socio-biological crisis in which individual behavior plays a central part. In this discursive project, infertility, and consequently low fertility, is often located as an information problem in the population.

From 2013, we find a portrayal in the media of fertility counselling, an experimental set-up at the university hospital in Copenhagen in 2011 to offer individual fertility assessment and since then spread to other hospitals. The apparent relevance and success of these clinics are storied through reports on long waiting lists, first in the capital area and later in clinics in Jutland. The fertility specialists are quick to establish that fertility assessment appears to have a positive effect on reproductive delay (“Fertility counselling put child production into action”, press release University Hospital of Copenhagen, 27 July 2014). In an op-ed on fertility counseling aimed at other medical professionals, the initiators explain how the clinic is modeled after the family planning clinics of the 1970s but with a “pro-fertility angel” (“Fertility counselling is a new concept”, Medical Weekly, 26 November 2016). Thus, fertility assessment and counseling are framed within a discourse of empowerment and reproductive autonomy, but also as response to demographic changes: increased age of first-time mothers, the fact that 9% of Danish children are born following assisted reproduction and a fertility rate “of 1,7 per woman which is below the replacement rate of 2,1 which is required to sustain the size of the population if we disregard immigration” (“Fertility counselling is a new concept,” Medical Weekly, 26 November 2016).

Importantly, the discursive framing of fertility awareness as empowering information was contested in 2015 when two fertility awareness initiatives collided. In the same week, the municipality of Copenhagen put up posters across the city asking: “Have you counted your eggs today?” and “Are they swimming too slowly?” followed by the national television channel DR broadcasting a heavily advertised live show titled “Do it for Denmark” (Knald for Denmark).Footnote 1 The premise of the show was that “Danish couples are having too few children, stating that if we are to uphold the size of the population we need 2.1 child per couple, but we only have 1.7’” (“Now we do it for Denmark”, dr.dk, 2 October 2015). On this demographic background, the intension of the TV-show was to educate the public about fertility and “to provide people with a qualified foundation to assess whether there is actually room for more children in their lives” (“Now we do it for Denmark,” dr.dk, 2 October 2015).

The timing was coincidental, as Copenhagen Mayor of Health and Care, Ninna Thomsen, responsible for the poster campaign, noted in the media. Here, she further asserted that the intention of the municipality was never to push people to have children, but to educate about the “challenges of postponing childbearing” (“Campaign spurs egg debate,” Amagerbladet, 20 October 2015; “Debate: Fertility campaign is information”, Information, 20 October 2015). As the Mayor of Health, her hope was that information would prevent “so many people from needing fertility treatment in the future”, she stated (“Campaign spurs egg debate”, Amagerbladet, 20 October 2015) contributing to the discursive project of constructing fertility awareness as a prevention intervention, and thus a public health initiative.

The pronatalism of the tv-show and the campaign became the center of a critique in the media (e.g., “Fatherland fuck” Information, 14 October 2015) in which especially the campaign was positioned as unwanted state interference in (women’s) reproductive decision-making. A newspaper article reported that a significant number of women posted photos of their fridge supply of hen’s eggs on the municipality’s Facebook page with comments like “Now I have counted my eggs, can I decide over my uterus now?” and “As a vegan, I don’t have any eggs, and I don’t think I want children—can that be my decision?” (“The Facebook page of municipality hit by egg photos—it is hilarious,” nyheder.tv2.dk, 8 October 2015). Another op-ed titled “Fuck no, I have not counted my eggs today” (Information, 13 October 2015) pushed back on the patronizing tone of fertility awareness to reclaim women’s right not to have a reproductive plan. This op-ed also challenged the link between low fertility and labor shortage, pointing to the subject of immigration, as the author states, “I can only say that my care worker can be brown” (“Fuck no, I have not counted my eggs today,” Information, 13 October 2015). However, including the question of immigration as a solution to the problem is rarely addressed in the debate.

The biomedical ambition to educate the Danish population about fertility problems is further visible in the periodic attempts to add the subject of fertility decline to the sexual education curriculum, a project the fertility specialists share with the Danish Family Planning Association in the advocacy to provide sexual education beyond elementary school. In this debate, the proposition is that focus should not only be on contraception, but also on teaching young people about fertility so they know how to become pregnant when they want to (e.g. “Fertility is not part of the sex ed curriculum. According to experts that is a mistake”, Information, 11 January 2021).

Reflecting the difficulties of reaching this goal, the media archive reveals how, in 2019, the Danish health authorities attempted to systematize a new type of preconceptual counselling. In a draft of new guidelines on pregnancy and birth care, it was suggested that general practitioners should discuss future pregnancy intentions with all women between the ages of 18–30, for instance, in relation to pap smear testing or birth control prescription (Danish Health Authorities 2019). However, like the campaigns, this suggestion was met by criticism and not realized. Not only was the exclusive focus on women problematised, but interestingly the general practitioners also refused to “intervene uninvited into people’s baby plans” (“Doctors do not want to provide uninvited family planning advice,” Jyllandsposten, 7 June 2020). Importantly, this rejection sums up a position taken by the few politicians who appear in our material who acknowledge infertility as a medical issue that needs attention, but position reproductive decision-making as belonging to the realm of private life.

The future of the welfare state: between welfare contractualism and necessary adaptation

While labor shortage has been a recurrent theme in the biomedical problematization of infertility as a societal problem, in 2019, the problem of sustaining the welfare state takes center stage as two op-eds turn up the volume of alarmism around low and falling fertility rates. Interestingly, these op-eds also embody new interdisciplinary collaborations.

Under the headline “The alarm is ringing: The Danes have way too few children” (Politiken, 12 April 2019), Søren Ziebe from the university hospital in Copenhagen and Ole Sohn, a former minister of health and, at the time, head of board at the Danish sperm bank Cryos, argue that “the reproductive sustainability of Danish society is under pressure.” While also pointing to widespread infertility as part of the problem, their main concern is “the societal model” which calls for education before reproduction and therefore supports delayed entry into parenthood. While their call also addresses the need for political action as well as more research, their problematization of low fertility reveals around the notion of the “generational contract” which the current societal model does not “take seriously” (“The alarm is ringing: The Danes have way too few children,” Politiken, 12 April 2019). With reference to the figure of the replacement rate, they stress that if the Danes wish to keep their level of welfare, such as free education, good healthcare, and see stable retirement ages, there needs to be a better balance between the recipients of welfare (children and the elderly) and those who contribute to welfare (taxpayers). Thus, the notion of reproductive sustainability is tied to welfare state logics of redistribution, but also draw on a type of welfare contractualism (Lister 1998) in which the citizens are called upon to understand their reproductive responsibility.

In the context of our analysis, the way Ziebe and Sohn mobilize the notion of sustainability is noticeable. Just as the scale of the ‘sperm crisis’ is construed by comparison to the climate crisis, the notion of reproductive sustainability works to convey a message about the importance of attending to the problem of low fertility, in the public but also in private life:

Today, expressions like ‘the green bottom line’ and ‘environmental sustainability’ are an integrated part of our thinking and the jargon in both public and private spaces. We wish that reproductive sustainability enjoyed the same attention. Both for the sake of society and for the individual. (“The Danes have way too few children”, Politiken, 12 April 2019)

Yet, as the quote suggests, while drawing on sustainability rhetoric, their vision of ‘reproductive sustainability’ remains disconnected from the population-environment nexus, leaving reproductive sustainability as a national matter.

A few months later, the notion of ‘underpopulation’ enters the debate with another interdisciplinary duo of fertility specialists, an andrologist and an anthropologist, who position that a generalized ‘we’ should react to the future scenario of ultra-low fertility which already poses “an existential threat in large parts of the world.” (“If we don’t react, the dramatic fall in the birthrate will continue” Politiken, 8 September 2019). Like Ziebe and Sohn, they call for more knowledge about the reasons why fertility rates are dropping as the starting point for finding “solutions that can prevent our descendants from living in societies characterized by unwanted underpopulation.” (“If we don’t react, the dramatic fall in the birthrate will continue”, Politiken, 8 September 2019).

Importantly, while the warning is nationally oriented, the mobilization of ‘underpopulation’ is more directly in keeping with ongoing debates about global population growth, that we also turn to briefly. Skakkebæk and Wahlberg for instance note that it might seem “unreal and strange” to frame low fertility as one of the biggest societal problems at “a time where the number of people in the world keeps rising and the strain of humanity on the climate and biodiversity is all too clear” (“If we don’t react, the dramatic fall in the birthrate will continue,” Politiken, 8 September 2019). Thus, they touch upon the repro-paradox that we discuss in this article. Yet, through this comparison, they propose that being too few is a more immediate threat, not only for the Danes, but for more than half of the world's population who now live in “low fertility countries.”

Importantly, Skakkebæk and Wahlberg seem to advance what can be conceptualized as an adaptation discourse that stand in contrast to the idea that the Danes can be motivated to behave differently. This is emphasized a few days later when Wahlberg states to a journalist that “independently of whether one thinks it sounds good or bad with more people, we have not discussed how to organize our societies, when their existing structures break down.” (“We are committing demographic suicide, and nobody is talking about it,” Information, 23 November 2019). In the journalistic framing, an apocalyptic tone is emphasized by the recycling of the Spanish conservative discourse of ‘demographic suicide’ (Pérez-Caramés 2017), which interestingly suggests a certain intentionality, as is the discourse of public neglect that runs through the entire debate about the fertility crisis. In contrast to the fertility awareness discourse, the adaptation discourse is more clearly oriented at the political level addressing the need to plan for a low-fertility future. Thus, the adaptation discourse locates the fertility crisis as an unavoidable structural crisis already unfolding. Interestingly, it somewhat decenters reproductive delay by referring to the unstainable pressures on young people as well as on our biologies. In contrast to the many articles in this period which provide advice on how the individual man can improve his sperm quality, Skakkebæk and Wahlberg frame poor sperm quality as the consequence of industrialization and pollution. Hereby, as they decenter individual behavior through the image of toxic ecologies as the cause of infertility, they provide another type of fearful attachment to environmental deprivation than the climate crisis debates to which we turn briefly.

The notion of underpopulation materializes how the repro-paradox is cementing in the Danish debate. The fertility crisis is positioned as eagerly severe as the climate crisis, but much more neglected. ‘Too few’ (re)emerges as a competing populationist discourse to the problem of ‘too many’ that has shaped climate crisis debates and to which we now turn to explore how ideas about reproductive sustainability are mobilized in this debate.

Climate crisis, ‘overpopulation’, and reproductive choices in a global world

In recent years, the climate debate has also focused on overpopulation, and this has led many young people to talk about not having children. (“More people never have children: A cultural breakdown may be on the way,” Jyske Vestkysten, 10 July 2021).

In this section, we analyze the media debates on reproduction in the context of the climate crisis. Search terms such as ‘fertility climate,’ ‘opt-out children climate,’ and ‘overpopulation children climate’ yielded very few hits in the first years of the period. However, from 2019, following the dire predictions of climate emergency in the 2018 IPPC report, the debate intensifies. The articles increase in number from 5 in 2018 to 16 in 2019. At the same time, there is a shift in focus. Whereas the early debates are dominated by political discussions around the topic of ‘overpopulation,’ more personal stories on climate and reproduction enter the media from 2019 onwards, especially centering young individuals. The increase in news articles, as well as the changes in which stories are told and by whom, must be seen in the context of new young climate activists entering the media, including social media, around this time, e.g., Greta Thunberg’s FridaysforFuture movement (from 2018). As studies show, climate change has been the subject of increased attention in the minds of young people, not least because of activists like Thunberg who have voiced the younger generation’s concerns about the planet (Fisher 2016).

As in the previous section on fertility crisis, we will below identify and analyze three overall themes in the media debates. The themes are interconnected due to their embeddedness in the agenda on climate but differ in their main message. Besides being identified thematically, they to some extent present a temporal process from early to late in the period of our search. While new themes emerge throughout the period and come to dominate the debate, previous ones continue to feature in the media. Also, the three themes are characterized by a blend of voices, from shorter posts by laypersons to op-eds by experts and journalistic articles using experts as well as individual stories.

Overpopulation and climate as a political field

Debates on overpopulation as a political field occupy the media throughout the whole period, but especially dominate the period up to 2019. Overall, debates about overpopulation and the climate address the political level, taking place as negotiations about whether overpopulation is in fact a problem, which parts of the world are overpopulated, and whose responsibility it is to limit the population in accordance with the climate crisis. Like the debates on (in)fertility and underpopulation, a large part of the debates unfolds around criticism of political ignorance, but now targeting the problem of overpopulation as visualized in a plea made by a group of climate researchers in the spring of 2019.

(I)t seems that many politicians and opinion leaders have forgotten, or do not want to discuss the population in the equation. Without population control, it will be difficult for our children and grandchildren to achieve a healthy and rich life in a peaceful world with still a bit of space for nature and birdsong. In fact, we also believe that even in Denmark there should be a gradual reduction in the population, although this is of course a challenge with our age composition.

(“Debate: Without control of population figures, the future for the climate, for example, looks bleak”, Jyllands-Posten 30 April 2019)

Reflecting how the neo-Malthusian rhetoric of population control has become naturalized within climate science and environmentalism (Bhatia et al. 2020; Robertson 2012), the researchers’ plea is not unique. It is repeated later in 2019, as the Alliance of World Scientists issues a global warning on the climate emergency, casting “family planning” as the means to address global population growth (Ripple et al. 2020).

Political sensitivity is a constant claim within this theme, under which population control is staged as a necessary but controversial political intervention central to solving the climate crisis. The controversial nature is, for instance, reflected in a post, issued in the wake of the scientists’ appeal:

The world's overpopulation is the biggest and most fundamental problem of the climate crisis. But that fact is the most difficult and politically difficult thing to talk about because it calls for interventions that are unacceptable for the entire political spectrum.

(“Debate: When facts become too politically dangerous,” Berlingske, 25 April 2019)

Several posts refer the political silence on this topic to its proximity to racism or the precarious case of China’s one-child policy, illuminating an awareness of the problematic histories of population control, which feminist researchers have addressed for decades (Yuval-Davis 1997; Hartmann 2016; Bhatia et al. 2020), but also making central the divide between rich and poor countries on matters of (over)population. Pivotal to this debate is a negotiation partly of where to place responsibility for the climate crisis and partly of defining responsibility for mitigating climate change. Voices from lay people mingle with representatives from various institutions, such as the humanitarian organizations DanChurchAid and Care Denmark. The various voices agree that overpopulation poses a threat to the sustainability of the planet but disagree about which parts of the world are overpopulated, that is, where interventions are needed. In one of the earlier and more radical debate articles, the DanChurchAid is criticized for saving the lives of many children who would otherwise die of hunger every day in developing countries, as the world is on course for disaster due to overpopulation (“Completely wrong! Aid to the world's poorest does not lead to overpopulation”, Kristeligt Dagblad, 16 February 2014). Other less radical but continuously contested posts point to measures, such as a one-child policy, to limit overpopulation in countries with the most people.

The Chinese saw the writing on the wall when they introduced the one-child policy. I think that this is what we must do. All the countries where the greatest overpopulation occurs could be encouraged to introduce that policy.

(“Debate: The climate”, Berlingske, 28 April 2016)

Identifying the Global South as being ‘too overpopulated’ and thus responsible for solving the problem of overpopulation generates counter-responses, pointing toward the responsibility of Western countries.

The world can bear more poor Africans on both the climate and food accounts. We are already in the middle of both a climate and a food crisis and more Africans is not the problem. We are the problem.

(“Debate: Blinders. Overpopulation is not the problem,” Politiken, 26 October 2014)

Notably, ‘We are the problem’ moves the focus to consumption and seemingly away from matters of reproduction. The rationale for turning accountability for the climate crisis away from poor countries is expressed in terms of the West's large unsustainable energy emissions that have created climate change:

In Denmark, we have an average discharge per person of eight tons of CO2 per year. In Malawi, they have a release of approximately 0.1 ton.

(“Completely wrong! Aid to the world’s poorest does not lead to overpopulation,” Kristeligt Dagblad, 12 February 2014))

Again, mobilizing a particular kind of numeric data, this argument articulates the injustice of poor countries being ascribed responsibility for climate-damaging practices prompted by rich countries.

What happens, however, is that when the climate crisis becomes about consumption, setting up a comparison between people’s emissions in the Global South and those in the Global North, a problematization of population gets re-established, but now in a Western context.

It is the children of the rich, our children, who are going to be the problem. The richest 10 percent of the world’s population account for almost half of human CO2 emissions. (…) Denmark is among the richest countries in the world. If we point at developing countries and say that they are not allowed to have more children, while we discuss taxes on air travel, then we have a much bigger problem.

(“Debate: A one-child climate policy? Morally and logically wrong,” Politiken, 25 April 2019)

Thereby, it is not ‘their’ but ‘our’ reproduction which is unsustainable. This problematization occurs in media debates, where some argue that the problem is a climate-destructive overpopulation in both the Global South and the Global North, while others exclusively problematize overpopulation in the Western context. Emerging headlines, such as “Do you want to save the climate? Then stop having children” (Berlingske, 11 August 2017), not only place Western reproduction as a main threat to the climate, but also redirect attention to the individual’s reproductive choices.

Overpopulation as the reason for individual reproductive choices

Today, two children are seen as the ideal by the majority in the Western world. Not too many, not too few. But if we really want to reduce our CO2 emissions as much as possible, the most effective solution is to have one fewer child than we intended. This corresponds to reducing CO2 emissions by 58 tons per year for each parent.

(“Debate: Climate-irresponsible to bring children into the world,” Kristeligt Dagblad, 16 November 2017)

In 2017, a study by Kimberley Nicolas, a researcher from the University of Lund in Sweden, generated a series of articles that spoke about climate-friendly lifestyles. Here, having fewer children was identified as the main component in living a sustainable life. “We recognize that 6this is a deeply personal choice, but we cannot ignore the enormous effect on the climate that our lifestyles have,” Nicolas said, and went on to talk about how she and her partner are involving this finding in their personal considerations about having children (“An alternative family life can save the world,” Kristeligt Dagblad, 15 July 2017).

From 2018, the political debate about overpopulation in the media starts to include overpopulation as a factor in individual reproductive decisions. While previous problematizations of overpopulation and climate crisis were characterized by someone pleading for what someone else should do, an ‘I' or ‘him’ and (most often) ‘her’ who does not want children due to overpopulation begins to occur. From 2020, especially, these individual stories take hold in the Danish media. Titles such as “Climate crisis causes women to opt out of children” (IN 30 January 2020) and “Childless in the name of the climate” (Weekendavisen 11 November 2021) show how the phenomenon has become rampant in the media. Many of the articles mention celebrities such as Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s stopping at two children due to overpopulation or the singer Miley Cyrus’ decision not to give birth and raise children “because the earth is angry” (“Antinatalism—no children, please,” Psykologi 20 January 2020).

In an article about a 20 year-old woman who aims to live as CO2-neutral as possible, the question of children is introduced as part of an ethical lifestyle:

This means, among other things, that she only wears recycled clothes, likes to eat surplus food, and never wants to fly on holiday again. (...) And she is not sure that she wants to have children either. Whether it is ethically justifiable, when we already have overpopulation, in relation to the way we live.

(“She calls herself a climate realist: ‘I can't be indifferent’,” Jyllands-Posten, 14 April 2019)

What happens within this line of argumentation is that reproduction, whether you want children or not, comes under the same rationale as other aspects of a sustainable lifestyle—avoiding air travel, reducing meat intake, and buying second-hand clothes. Debates about the unsustainable choice of reproducing either refer directly to ‘overpopulation,’ as in ‘the earth does not need more people,’ or to ‘the child as a consumer who will burden the planet’ (see also Bodin and Bjørklund 2022).

However, placing children in the category of sustainable choices arouses astonishment as well as direct resistance. For instance, an article titled “It is disturbing that more young people choose not to have children for the sake of the climate” (Kristeligt Dagblad, 27 September 2019) features an interview with the British sociologist Frank Furedi who is critical about the “trend” in which infants come to be seen consumers and “as a threat to the earth.” Furedi suggests that eco-reproductive concerns are an expression of “a deeply pessimistic view of humanity” and “a new generation of adults who do not want to be adults.”

In the media, something new happens when overpopulation moves from the political level into personal debates on reproductive decision-making. On the one hand, placing ‘kids and steaks’ (“Children and steaks are lovely—but dangerous for the environment,” Flensborg Avis, 4 July 2019) on the same scale of inappropriate climate-related behavior generates cultural resistance: “How can you degrade newborn children to climate threats rather than the enormous opportunities new life brings?” (“Blog post: Children are not harming our climate,” 180 grader, 16 September 2018), as one post asks. On the other hand, placing reproduction on the climate agenda on an individual level is about something more than the well-being of the planet. The debates are still about sustainable reproduction in a time of climate crisis, but they become more oriented toward the future of unborn children. We investigate this further under the next theme.

Reproductive responsibility in a future of climate crisis

Should your life, when you reach the age of 50 or maybe even 80, be tolerable, the highways would already be deserted today, the supermarkets would be empty of meat and imported fruit, while the entrance to coal mines all over the world would be walled off (…).

(“Dear unborn grandchild, you are being born into a war that the rest of us have declared against the planet,” Politiken, 25 November 2018)

In an op-ed from 2018, a prominent Danish author addressed the present reluctance to act on the climate crisis starting from the future interests of his unborn grandchild. He polemically asked if we are leaving the world so wretched that the future generation's answer to our irresponsibility is a “birthstrike.” Interestingly, in the following years, the media is full of articles that specifically deal with young people’s birthstrike. Some articles discuss the UK-based activist Blythe Pepino and the BirthStrike campaign, but most address the reproductive doubts of young Danes with titles such as “Astrid doesn’t want children” (NordJyske, 25 February 2021) and “He made a significant decision: It is the world's wildest choice not to have children” (Politiken, 2 August 2021).

It is no longer overpopulation nor the carbon footprints of having children, which dominate the media debates. Instead, emotions such as climate anxiety and fearful considerations for the unborn child’s future come into play as motivations for young people's reproductive choices.

Media coverage of eco-reproductive concerns tends to be framed by sensationalism, as in the following quote:

A young woman, Charlotte Jensen, sits in a chair in my office and says shockingly and bluntly: ‘I don't think I want to have children because I fear the world, they will grow up in.’ (...) I have yet to hear anyone react so radically to a bleak future.

(“The climate crisis: Baby bonanza,” Weekendavisen, 7 February 2020)

The narrative voice’s bewilderment points to the cultural unrecognizability of both not wanting children and not wanting them because of climate concerns. Several articles describe an increasing tendency to remain childless by choice, where one of the reasons given for this choice, but not the only one, is climate considerations: “More people never have children: A cultural breakdown may be on the way” (JyskeVestkysten, 10 July 2021).

In one article, we hear about a young woman who is part of this cultural breakdown. The main character, Astrid, tells how overpopulation and climate crisis have been at the back of her mind, but the main reason why she and her husband do not want children is because they do not want to give up their personal freedom. Negotiations about whether it is sustainable to reproduce due to climate concerns are part of a debate on reproductive choices that says that having children is not an inevitable part of life. This corresponds to studies finding that staying childfree is often not only because of climate concerns but plays together with other considerations (Schneider-Mayerson and Leong 2019).

Furthermore, climate anxiety begins to take up more space in media coverage of individual stories on reproductive choices. Titles such as “Climate anxiety makes young people hesitate to have children” (TV2, 1 January 2022) and “Are you afraid of the future? ‘Absolutely crazy’ is the answer. This has caused 19 year-old Sara to make a drastic choice” (Berlingske, 3 January 2022) point to the emotional aspects of including the climate crisis in personal thoughts about reproductive futures. In the latter article, we hear about 19 year-old Sara, who has decided not to have children if the international community does not uphold the Paris Agreement. This is not so much an expression of an actual birthstrike, that is, to pressure politicians to act, but out of fear for the future:

I would like to have children if the world looked different. If I was sure I could give my potential children a safe future. A much fairer world. Unfortunately, I don’t see that. I wish I did.

(“Are you afraid of the future? ‘Absolutely crazy’ is the answer. This has caused 19 year-old Sara to make a drastic choice,” Berlingske, 3 January 2022)

In this period, journalists begin to invite psychologists to comment on the phenomenon of ‘climate anxiety,’ arguing that anxiety among young people should be taken seriously (“Climate anxiety makes young people hesitate to have children,” TV2, 1 January 2022). In comparison to the speculative tone of earlier articles, these unfold in more explanatory or descriptive ways. The articles, however, still evoke debate. A post directly responding to Sara’s story distances itself from the BirthStrike movement, calling it one of the saddest things to imagine. It continues in a quite paternalistic way:

In my best opinion, children and young people should be more concerned with being good friends than with big and abstract problems around the world. As parents and adults, we have a special responsibility here. The children and young people growing up in these years especially need us adults to lift some of the responsibility from their shoulders.

(“Young people’s climate anxiety is worrying. Adults are obliged to give children and young people a belief in the future,” Kristeligt Dagblad 16 January 2022)

With the shift toward the future of the child and individual anxieties, the debates become distanced from the subject of sustainable reproduction. Or perhaps it is rather a shift in the meaning of sustainability from being about human numbers to a matter of the world as we know it being sustained into the future. If the future world is not sustainable, neither is reproduction.

Concluding discussion: the repro-paradox of sustainable reproduction

As we have demonstrated in this article, two distinct debates about sustainable reproduction have taken place in the Danish media over the last decade. While both evolve around demographic worries, their problematizations contrast between scenarios of being ‘too few’ and ‘too many.’ Rather than debating which numbers count, the aim of the article has been to show how demographic ‘truths’ are mobilized in the quest for sustainable reproduction, that is, how numbers come to count in the formulation of societal problems (Dow and Lamoreaux 2020; Whittaker 2022). We have shown how discourses of ‘overpopulation’ and ‘underpopulation’ co-exist in the Danish context and how they are mobilized by a variety of agents belonging to different social worlds, with climate science and activism on the one side and fertility specialists and reproductive medicine on the other. We find that the distinctive social worlds are central in the discursive meaning-making of sustainable reproduction, seeing the population problem as, respectively, a national or a global matter.

Like the Danish media debate, much of the existing literature on demographic anxieties tends to focus exclusively on one of the two agendas raising concerns about either the ethnocentric and pronatalist responses to falling fertility rates (e.g., Whittaker 2022) or the neo-Malthusian rhetoric of the climate crisis debate (e.g., Sasser 2017, 2024). Bringing the two agendas together, as we have done in this article, makes it possible to designate what we would call a repro-paradox. The notion of repro-paradox has similarities to Huang’s work on ambi-natalism (Huang 2022). While ambi-natalism implies an ambivalent transferal of the Chinese state’s turn from anti-natalism to pronatalism into the reproductive journey of individuals, the repro-paradox plays out between a Danish national call for more reproduction and a globally oriented call for less reproduction. Both terms highlight the complexity in how reproductive agendas unfold and shift and both emphasize the context as important in how ambivalence and tension play out. Thus, our identification of the Danish repro-paradox emphasizes the importance of understanding not only the specificities of how nationally oriented pronatalist welfare state agendas develop, but also how they collide with local interpretations of the global climate crisis politics (Homanen and Meskus 2023). The notion of a repro-paradox thus captures the tensions between these agendas, as unfolding sociopolitical orientations, and the dilemmas that exist in having to accommodate contrasting quests for sustainable futures.

In our analysis, we identify Danish biomedicine as a central social arena for biopolitical intervention in low fertility as we center the medically driven fertility crisis agenda, which stands in contrast to for instance the political call from Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg who in her 2019 new year’s address told the Norwegians to have more children (Kristensen 2020) or how falling fertility rates have been addressed in population policies by the non-governmental organization Family Federation of Finland (Homanen and Meskus 2023). Hereby, the article adds to a growing body of literature exploring demographic anxieties in the context of the Nordic welfare state. What stands out about the Danish context is the bridge between public health strategy and the articulation of underpopulation as a public concern. As we have showed, in both the debate about user fees on infertility treatment and prevention-oriented fertility awareness advocacy, individual fertility issues are constantly connected to the future of the nation state through demographic metrics such as the replacement level. The focus on poor sperm and aging eggs—and, not least, the anticipatory logics of potential trauma that they are entangled in—is not only a particular kind of ‘molecular gaze’ characteristic of late modern biomedicine (Rose 2007). The quest for fertility awareness, which is otherwise positioned as reproductive empowerment, also advances a pronatalist imperative to mind one’s fertility, not only to prevent infertility but also for the financial sustainability of the welfare society. Even when, toward the end of the search period, the entry of notions such as underpopulation and reproductive sustainability connects the biopolitical commitment to low fertility to the global perspectives of the climate crisis, the discourse of the fertility crisis recenters national futures as the most pressing matter of concern.

In our examination of the media debates, we find that the tension between the two agendas arguably increases during the period 2010–2022, relative to the intensification of both crisis narratives, but also due to discursive shifts and engagements on both sides. Central to the intensification of the paradox is the relocation within the climate crisis debate of the population problem from the Global South to the overconsuming populations of the Global North, a shift that, however, is still based on neo-Malthusian logics of resource deprivation and being ‘too many’ (heavy consumers) (Bathia et al. 2020; Sasser 2024). This shift is further co-constitutive of the move from discussions on political responsibilities of mitigating overpopulation to individual reproductive responsibility through the logic of the carbon footprint (Wynes and Nicolas 2017). We see how the problematization of the consuming Western individual enters the Danish debate, but also how the discourse of responsibility shift between consumption patterns and existential fears about the future that potential children will have (Bodin and Bjørklund 2022; Sasser 2024). Demonstrating how eco-reproductive concerns play out in the media, the article adds to the small but growing body of literature discussing the entanglements of the climate crisis and reproductive decision-making (Schneider-Mayerson and Leong 2019; Helm et al. 2021; Nakkerud 2021; Scheider-Mayerson 2021; Bodin and Björklund 2022; McMullen and Dow 2022). Little of this research has looked at how these concerns present in mainstream media and our analysis shows the multiple arguments and agents that shaped the debate as it evolves over time.

Our analysis highlights how demographic anxieties are a central part of the ways in which sexual stewardship (Sasser 2017) is constituted and promoted through public debates where (young) people are called upon to have fewer or more children for the sake of a greater good. A central argument is how demographic anxieties, though formulated at the population level, always come to implicate individuals in different ways. As Dow and Lamoreaux (2020) also problematize, the solution to population problems often seem to slide to the level of individual decision-making. This is visible in the pronatalist discussions about ‘fertility awareness’ and ‘generational contracts’ but is arguably also a result of the climate agenda raising concerns about procreation in the Global North. The notion of the repro-paradox, however, also highlights the unfolding conflict of how young people in contemporary welfare societies, such as the Danish, are simultaneously called upon to have fewer and more children. Future research should aim to explore how such tensions plays out in lived experience.

Data availability

Media content is available through Infomedia database. Article archive is not available for sharing.

Notes

The TV show shared its title with a 2012 commercial from the Danish travel agency Spies that went viral and received several advertisements awards but did not provoke much public debate in the Danish media.

References

Almeling, R. 2015. Reproduction. Annual Reviews of Sociology 41: 423–442.

Bhatia, R., J.S. Sasser, D. Ojeda, A. Hendrixson, S. Nadimpally, and E.E. Foley. 2020. A feminist exploration of ‘populationism’: Engaging contemporary forms of population control. Gender, Place & Culture 27 (3): 333–350.

Bodin, M., and J. Björklund. 2022. Can I take responsibility for bringing a person to this world who will be part of the apocalypse!?: Ideological dilemmas and concerns for future well-being when bringing the climate crisis into reproductive decision-making. Social Science & Medicine 302: 1–8.

Clarke, A.E. 2018. Introducing. In Making Kin Not Population, ed. A.E. Clarke and D. Haraway. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Clarke, A.E., and D. Haraway, eds. 2018. Making Kin Not Population. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Clarke, A.E., C. Friese, and R.S. Washburn. 2018. Situational Analysis. Grounded Theory After the Interpretive Turn. Los Angeles: Sage.

Danish Health Authorities. 2019. Draft consultation material guidelines on pregnancy care. https://hoeringsportalen.dk/Hearing/Details/63515. Accessed 1 Nov 2023.

Davis, D.-A. 2019. Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth. New York: New York University Press.

Dow, K., and J. Lamoreau. 2020. Situated kinmaking and the population ‘problem.’ Environmental Humanities 12 (2): 475–491.

Fisher, S.R. 2016. Life trajectories of youth committing to climate activism. Environmental Education Research 22 (2): 229–247.

Franklin, S. 2022. Foreword. Medical Anthropology 41 (6–7): 600–601.

Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. London: Duke University Press.

Haraway, D. 2018. Making Kin in the Chthulucene: Reproducing Multispecies Justice. In Making Kin Not Population, ed. A. Clarke, and D. Haraway. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Hartmann, B. 2016. Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Helm, S., J.A. Kemper, and S.K. White. 2021. No future, no kids-no kids, no future? An exploration of motivations to remain childfree in times of climate change. Population and Environment 43: 108–129.

Hendrixson, A., D. Ojeda, J.S. Sasser, S. Nadimpally, E. Foley, and R. Bhatia. 2020. Confronting populationism: Feminist challenges to population control in an era of climate change. Gender, Place & Culture 27 (3): 307–315.

Homanen, R., and M. Meskus. 2023. Population anxieties in constituting Nordic welfare state futures: Affective biopolitics in the age of environmental crisis. BioSocieties. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-023-00300-3.

Huang, Y.L. 2022. Road of no return: Uncertainty, ambivalence, and change in IVF journeys in China. Medical Anthropology 41 (6–7): 602–615.

Huang, Y.L., and C.L. Wu. 2018. New feminist biopolitics for ultra-low-fertility East Asia. In Making Kin Not Population, ed. A.E. Clarke and D. Haraway, 125–144. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Krause, E.L. 2001. ‘Empty cradles’ and the quiet revolution: Demographic discourse and cultural struggles of gender, race, and class in Italy. Cultural Anthropology 16 (4): 576–611.

Krause, E.L., and S. De Zordo. 2012. Introduction. Ethnography and biopolitics: Tracing ‘rationalities’ of reproduction across the north–south divide. Anthropology & Medicine 19 (2): 137–151.

Kristensen, G.K. 2020. Ofentlige samtaler om fruktbarhet i dagens Norge. Mellom nasjonal velferdsstatskrise og global klimakrise. Tidsskrift for Kjønnsforskning 44 (2): 152–216.

Lister, R. 1998. Citizenship: Feminist Perspectives. Hamshire and New York: Palgrave.

McMullen, H., and K. Dow. 2022. Ringing the existential alarm: Exploring birthstrike for climate. Medical Anthropology 41 (6–7): 659–673.

Meynell, L., et al. 2023. “Is it okay to have a child?”: Figuring subjectivities and reproductive decisions in response to climate change. Subjectivity. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41286-023-00168-5.

Nakkerud, E. 2021. Ideological dilemmas actualised by the idea of living environmentally childfree. Human Arenas. 6: 886.

Ojeda, D., et al. 2019. Malthus’s specter and the anthropocene. Gender, Place & Culture 27 (3): 316–332.

Pérez-Caramés, A. 2017. The breakdown of consensus on pro-natalist policies Media discourse, social research and a new demographic agreement. In Loffeier, I, ed. B. Majurus, and T. Moulaert. Framing Age. Contested Knowledge in Science and Politics. London: Routledge.

Ripple, W.J., C. Wolf, T.M. Newsome, P. Barnard, and W.R. Moomaw. 2020. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience 70: 8–12.

Robertson, T. 2012. The Malthusian Moment: Global Population Growth and the Birth of American Environmentalism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Rose, N. 2007. The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sasser, J. 2017. On Infertile Grounds: Population Control and Women’s Rights in the Era of Climate Change. New York: New York University Press.

Sasser, J. 2024. At the intersection of climate justice and reproductive justice. Wires Climate Change 15 (1): e860.

Schneider-Mayerson, M. 2021. The environmental politics of reproductive choices in the age of climate change. Environmental Politics 31 (1): 152–172.

Schneider-Mayerson, M., and K.L. Leong. 2019. Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change. Climatic Change 163: 1007–1023.

Schultz, S. 2021. "The neo-malthusian reflex in climate politics: Technocratic, right wing, and feminist references. Australian Feminist Studies 13 (110): 485–502.

Whittaker, A. 2022. Demodystopias: Narratives of ultra-low fertility in Asia. Economy and Society 51 (1): 116–137.

Wynes, S., and K.A. Nicolas. 2017. The climate mitigation gap: education and governmental recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environmental Research Letters 12 (7):

Yuval-Davis, N. 1997. Gender and Nation. Los Angeles: Sage.

Zordo, S., D. Marre, and M. Smietana. 2022. Demographic anxieties in the age of ‘fertility decline.’ Medical Anthropology 41 (6–7): 591–599.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of the research project Responsible Reproductive Citizenship in Denmark in the 21st Century funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark, Grant #1028-00143B.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University. Funding was provided by Danmarks Frie Forskningsfond (Grant No. #1028-00143B).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bach, A.S., Breengaard, M.H. The repro-paradox of sustainable reproduction—debating demographic anxieties in the Danish media (2010–2022). BioSocieties (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-024-00330-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-024-00330-5