Abstract

Patient experiential knowledge is important for the quality and responsiveness of healthcare systems. However, it is not rare for patients to struggle to have their knowledge recognised as credible and valuable. This study explores how patient organisations work to adjust patient knowledge to formats recognisable and acceptable by healthcare governance decision-makers. Using the case of patient organisations in Russia, we show that such formatting involves changes in language, practices, and materiality that contribute to channelling patient participation into specific routes and forms while marginalising others. Channelling of patient participation, then, rather than being a result of direct coercion, emerges as a distributed process continuously co-produced by a multitude of actors, such as state administration, patient organisations themselves, patient surveys, consultative spaces, and normative acts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nowadays, patient experiential knowledge is widely accepted as relevant to the quality and responsiveness of health care and research (Callon and Rabeharisoa 2003; Mol 2008; Pols 2005). However, credentialed knowledge and experiential knowledge continue to have different value for decision-makers in healthcare governance (Hoļavins & Zvonareva 2022). The knowledge of medical professionals, researchers, and state administration is often treated as more credible (Kirkland 2012; Thompson et al. 2012) and valid (Martin 2008a, p. 38) than the knowledge of patients, which is acquired through everyday experiences of having a disease and receiving health care (Stewart 2016; Popay et al. 2003, pp. 2–4). This differential treatment is a significant obstacle to patients’ participation in healthcare governance, as their views and recommendations can be silenced and ignored (Stewart 2016; O’Shea et al. 2017).

In response, patients work on obtaining credibility to contribute to healthcare governance. Some acquire knowledge of (bio)medicine and learn to speak the language of biomedical scientists to be able to partake in deciding how diseases of concern are studied and how treatments are developed (Epstein 1996). Others systematically collect and formalise patients’ experiences of living with their conditions, aligning these experiences with the scientific episteme (Callon and Rabeharisoa 2003; Kerr et al. 2007). Patients might also claim credibility by referral expertise, that is, “expertise in one field [that] can be applied in another” (Collins and Evans 2002, 254), mentioning, for instance, academic training in social science or nursing to build their own credibility (Kerr et al. 2007, p. 400; Thompson et al. 2012, pp. 611–612).

What unites these and other strategies is the adjustment of patients’ experiential knowledge to the formats recognisable and acceptable by healthcare governance decision-makers. This study also explores how such formatting is performed by patient organisations (POs) in an effort to overcome silencing and disregard of patient experiential knowledge and to what effect. In contrast to most of the existing literature, however, we focus on patient participation in a nondemocratic context and explore the formatting work of POs in Russia. We argue that while patient knowledge is always formatted in certain ways when it is to be circulated in different arenas as existing literature shows, there are specificities of patient knowledge formatting in our case. These specificities stem directly from the circumstances of “consultative authoritarianism” our case is situated in Truex (2017) and include, first, that formatting is aligned with preferences and practices of the state administration and, second, that knowledge of medical professionals and scientists is to some degree devalued as well. Formatting of the individual patients’ experiential knowledge performed by the Russian POs contributes to channelling patient participation into specific routes and forms while marginalising others.

In what follows, we delineate theoretical perspectives on experiential knowledge, its credibility, and its involvement in healthcare governance. We then describe the research methodology, followed by a brief overview of the Russian healthcare governance system. Lastly, we discuss language, practice, and material transformations of patient knowledge and the channelling effect such formatting of patient knowledge has on patient participation.

Knowledge: experience, training, and credentials

Experts play an important role in governance, including the governance of health. Yet, who counts as an expert is a thorny question that has generated heated controversies over the definition of expertise and its use in decision-making. Although being a professional and having formal credentials is not a universal prerequisite for being accepted as an expert, certain professions, such as physicians and scientists, have expert status tied to them by default (Wynne and Lynch 2015). These professions have instituted formal certifications to mark degrees of expertise, which may be challenged but more often taken for granted.

Critical social science scholarship has highlighted how decision-making in the context of governance often includes the knowledge of accredited experts but excludes other relevant knowledges from being considered. For example, Irwin (1994) examined a case of risk assessment of the herbicide 2,4,5-T in the UK. The expert commission charged with advising the government on the matter insisted that 2,4,5-T is safe when used under recommended working conditions. Farmworkers, however, ridiculed the notion of ‘recommended working conditions’, claiming that these are impossible in practice and citing in support their experience in the field, where they have to spray “through thick undergrowth, in high winds, at the top of a ladder, in hot weather” (p. 113). Experts by training who were granted authority appeared to be out of touch with reality to farmworkers, yet farmworkers’ knowledge of herbicide use in practice was not considered relevant or credible.

This has been the fate of much experiential knowledge, including patients’ knowledge (Popay et al. 2003). Decision-makers in healthcare governance have questioned its credibility (Thompson et al. 2012; Kirkland 2012), validity (Martin 2008a, b) and the possibility of generalising personal experience (Caron-Flinterman et al. 2005, p. 2577). Nowadays, however, patient participation in healthcare governance is acceptable and even required by policies (Gibson et al. 2012) due to “democratic, consumerist or efficiency promoting intentions” (Olsson et al. 2020, p. 1454). This normative shift echoes wider debates around the role of ‘lay’ citizens in technoscientific decision-making (Jasanoff 2005; Callon et al. 2011). Thus, patients are now better positioned to have their knowledge recognised and accepted.

Yet, in practice, patients still have to work hard to have their knowledge recognised and taken into account in healthcare governance. Rabeharisoa et al. (2014) showed how POs perform this work. These authors demonstrated that POs mediate between the experiences of concerned people and other stakeholders, including policy makers, by translating experiences into the language of biomedicine and vice versa. By doing so, POs create hybrids of credentialed and experiential knowledge to make the latter politically relevant and widely perceptible. For instance, childbirth activists relied on an analysis of the clinical effectiveness of such procedures as episiotomy to craft space for women’s experiences, collected through the surveys they conducted (Rabeharisoa et al. 2014). Thus, the POs studied by Rabeharisoa et al. (2014) embed themselves in networks of experts by training and articulate experiential knowledge with credentialed one to make patients’ voices heard. Although patients’ involvement does challenge credentialed knowledge and reconfigure existing networks of expertise, credentialed knowledge is neither dismissed, nor does it lose its socio-epistemological dominance.

Although successful in articulating experiential knowledge and making patients’ voices heard, the formatting and standardisation involved in such articulation may also facilitate a division between acceptable and unacceptable forms of patient participation. In the study of public debates on the topic of nanotechnologies, Laurent (2017, prologue) provided an example of such division, in which the organisation of the debates with participants selected by the organisers worked to marginalise other forms of action, such as activist protests, by hiding and limiting access to the public debate venue for protesters. A study of the circulation of know-how for doing mini-publics by Voß et al. (2022) further highlights that such disequalising effects may be far from deliberate. Using the concept of infrastructuring to denote how flows of knowledge are configured, these authors show that the very act of standardisation to align understandings and strategies is linked to inevitable selectivity and “narrowing down the ways in which the innovation of democracy and the doing of mini-publics may be understood and performed” (pp. 121–122). In the case of healthcare governance, whereas officially sanctioned formats such as patient councils and neat contributions such as reports may be increasingly accepted, formatting patient knowledge to fit these arrangements may further marginalise other kinds of contributions, such as those involving affect and confrontation.

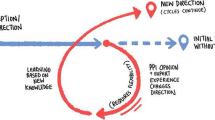

In this article, we discuss how the work of making patient knowledge fit healthcare governance conventions in Russia contributes to channelling patient participation into acceptable formats and directions. In contrast to existing studies that showed how POs translate experiential knowledge of patients into the language of biomedicine to feed this knowledge into healthcare governance, we show how patient experiential knowledge is made to fit the formats recognized and accepted by the state administration actors. Importantly, the resulting channelling is not a result of direct coercion by the authoritarian state. Rather, it is distributed, being co-produced by a multitude of actors, such as state administration, POs themselves, patient surveys, consultative spaces, and normative acts. This has led us to introduce the notion of distributed channelling of patient participation, which is presented in more detail below.

Methodology

Data collection

The analysed data were collected during the qualitative fieldwork within the framework of a larger research project on the channelling of patient participation by the Russian state. The data included semi-structured interviews, participant observations, and document analysis. We conducted 36 interviews with 31 research participants that lasted from 30 min to 2 h and 30 min. The interviewed research participants came from 16 Russian regions and 13 non-governmental patient self-help organisations. Research participants included 14 patients; 7 patient relatives; 5 medical professionals, including 3 patient council members and 2 POs’ leaders; and 5 third sector representatives, including 3 volunteering leaders of the NGOs and 2 think tank experts involved in assisting POs. All of them were also members of formal consultative bodies affiliated with the state, such as public councils. Observations included public councils’ meetings, conferences, roundtables, technical internal meetings, and everyday work of the offices of the patient organisation leaders. Analysed documents were treated as sources of both contextual knowledge and the practice of healthcare governance. They include key policy documents and legislation, as well as reports and other methodological materials about the work of patient organisations, including audio-visual sources.

Data analysis

The collected data were analysed using thematic content analysis. The analysis was guided by the key question of how patient knowledge features in state administration practice. Altogether, 73 documents, 31 interviews, and multiple observations were analysed. Initially, a selection of the documents corresponded to the goal of mapping healthcare governance actors and networks and identifying the “channelling” of patient participation by the Russian state. Patient “lay” expertise appeared to be sidelined—in contrast to a credible and recognised involvement of POs. Digging into this direction, the theme of formatting and formatting expertise was uncovered. Altogether, 49 codes were identified and grouped into 13 code groups. In total, 15 codes specifically covered the topic of expertise and the formatting work being done. As a result of the coding, several major themes related to formatting and various expressions of expertise, including formatting expertise, emerged This includes, among other things, “knowledge systems”, “constructiveness” (a channelled accepted form of patient participation), and “aggregation” (a process of collecting data on patients).

All names of the research participants, organisations, and toponyms are anonymised for ethical and safety reasons. The names used in the article were randomly selected from the Yevegeny Lukin “Bakluzhino Cycle” books.

Patient participation in Russia

The umbrella term patient organisations used in this article covers Russian non-state organisations as different as de facto one-man organisations and large unions focused on building capacity of other organisations. POs consist mostly but not exclusively of patients with life-changing and severe diseases. In some cases, these are relatives of sick people, who are members. Sometimes employees and leaders of POs do not share the health condition of their members, being either third sector professionals or medical professionals-turned-civic-activists. Although there might be some discrepancies about how to call organizations, in which non-patients and experts are present among employees and members, we call them POs because research participants themselves call their organisations “POs”. Additionally, the views of patients and professionals involved align on the matter of how to call their organisations. Moreover, even credentialed expert members of the POs are in most of the cases involved in these organisations as volunteers. Namely, both patients and professionals have their main day jobs, whereas POs—even the largest and most prominent ones—are being run in their free time. In the last 10–15 years, many POs, identifying themselves as a patient community, have contributed significantly to the key policy changes that benefit many of their members. Some examples include the federal programmes Seven High-Cost Nosologies of 2007 and Fourteen High-Cost Nosologies of 2011, both providing a framework for free or partly reimbursed medicine provision to patients with rare diseases, such as cystic fibrosis and haemophilia.

Apart from POs, Russian healthcare governance actors include medical professionals and scientists, private companies such as insurers and pharmaceutical companies, and state institutions. The latter include federal and regional Ministries of Health (MoH), Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare (Roszdravnadzor, a controlling body), which at the time of this writing was supervised by MoH, and Medical and Social Assessment Committees (MSE), under the supervision of the Ministries of Labour and Social Development, which are responsible for the assignment of disability status to citizens. This status provides eligibility for various types of government support, such as fully or partially reimbursed medicines, rehabilitation, and other care and health services. Roszdravnadzor is hierarchical, with regional branches strictly controlled by the federal Roszdravnadzor. By contrast, regional ministries of health are more independent of the federal ministry, as many budget decisions and day-to-day policies relevant to patients are implemented at the regional level. Other state institutions partly involved in healthcare governance are regional governors and committees attached to the President’s Administration, such as the Committee on Human Rights and Civic Affairs, as well as relevant committees and individual members of the parliament (MPs) in regional and federal parliaments.

Existing legislation provides a framework for patient participation in healthcare governance. The single most important piece of legislation on public health in Russia, Federal Law 332 “On Health Protection of Citizens”, explicitly cites participation as a right of patients in Articles 6 and 28. Moreover, an overarching idea of “patient-orientedness”, or incorporating patient perspective in governance, organisation, and provision of healthcare, is being cited regularly at expert meetings and conferences as a normative ideal (“Patient-orientedness is our priority”—the Federal Minister of Health Mikhail Murashko; “Patient-orientedness as the main vector for the development of healthcare provision by professionals with secondary special education”—the name of the conference organised by the Association of Nurses and the Pirogov Centre, a federal medical institution). This attitude towards patient participation resonates with support for public participation in areas seen as safe and apolitical by the state, as non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are provided with a framework to engage in social service provision (FL 7 ‘On Non-Governmental Organisations’, 1996, Article 2, amended in 2010 and FL 422 ‘On Social Service Providers’, 2014) and are given rights to contribute to policy-making (FL 82, 1995, amended in 2016, Article 27). Importantly, public participation is conceived in the existing legislation in Russia in terms of control, as exemplified by the eponymous FL 212 ‘On Public Control’ (2014). In short, public control refers to activities by non-state actors performed to verify the quality and legality of the state institutions’ work, including an analysis of the relevant legislation and its possible shortcomings (FL 212, Art. 4). As stated in Doc 44 ‘NGO Technologies of Public Control’ (Sergeeva et al. 2018, p. 14), and in Doc 58 ‘Best Practices of Socially Oriented NGOs in Health Governance’ (Zhulev 2015) “resolution of social tension” and maintenance of social stability are to be ensured by public participation, including participation of patients.

The delineated picture of patient and public participation in Russia can be understood as an example of consultative authoritarianism (Truex 2017). Consultative authoritarianism is dualistic in its support of public participation while legitimising the authoritarian regimes. Its key mechanism is what we call here consultative spaces. One crucial example of such spaces is public councils (obschestvennye sovety). The aforementioned FL 212 ‘On Public Control’ defines public councils as consultative bodies attached to state institutions to facilitate representation of the interests of third sector organisations, including POs (Article 13). First public councils were established already in 2009–2010, being mentioned in the Federal Law 32 ‘On Public Chamber’ (Article 20 point 2) as early as 2005, as well as in Presidential Order 842 (2006, amended in 2011) and Governmental Order 481 (2005). The creation of public councils has been largely a top-down process, with federal-level state actors searching for ways to channel public and, specifically, patient participation into practices and discourses that would not challenge the regime. For regional-level state actors, however, the creation of public councils unexpectedly turned into some degree of non-state actors’ control over their actions, which was often not desirable. In an attempt to contain the work of public councils, regional state actors would then seek to create councils that would either be completely inactive or unconditionally supportive of regional governments. Thus, members of public councils are usually pro-regime activists, professionals, and private sector representatives with the patient community being significantly underrepresented. Another way in which regional state actors would seek to contain the work of public councils is by refusing to hold their meetings unless the agenda is fully aligned with interests of the regional government.

Partly in reaction to the latter dynamic and in a general search for ways to make an impact, POs came forward with the idea of patient councils. Officially, these bodies came to be called councils of NGOs on the rights of patients, sovety obschestvennykh organisatsiy po pravam patsientov. Patient councils are affiliated with Ministries of Health and Roszdravnadzors, with the Federal Ministry of Health patient council established in 2012. Councils often allow POs to engage governmental stakeholders and recommend policy changes to benefit patient communities. Unlike public councils required by federal legislation, patient councils are created by state institutions voluntarily, and there is a stronger sense of informality, according to the interviewed research participants. Another difference is that patient council members are approved by the respective state institution, while members of public councils’ are approved by the pro-regime federal Civic Chamber and the regional Civic Chambers. All members of patient councils have to be third sector representatives. Although some of the members represent professional associations, the majority of the patient councils’ members represent POs. An invitation and approval by the state officials to join a patient council can be understood as a seal of acceptance of sorts granted to specific POs and meant to signify that this organisation has expertise and capability of working with the state. Prior to an invitation and approval, POs become known to the state actors through complaints, policy proposals, and court cases. When the complaints are considered well-written and not overly confrontational, policy proposals appear well-informed, and court cases demonstrate a PO’s proficiency in patient rights, healthcare system and state administration practice, POs are noted as those able to participate in healthcare governance. In general, there appears to be a shortage of such POs. Therefore, sometimes active individuals who persistently and successfully defend their rights to health care are encouraged by the state actors and/or those already involved in the work of patient councils to lead a dormant NGO or set up their own to be able to join a patient council.

In the course of our fieldwork, we observed both patient and public councils. Regularity of the meetings varied: the observed Syznovo region Roszdravnadzor patient council is being held monthly; another observed patient councils, in Ivnyak region Roszdravnadzor, is being held quarterly; whereas members of patient and public councils with Roszdravnadzor and the regional MoH in Kuropatinsk region said in the interview that their councils are being held irregularly. All councils mentioned in the interviews and observed have a chair, which is firmly supported by the councils’ regulations (Rus. polozheniya), which require a selection of at least one chair (with two co-chairs in the case of the federal MoH). Chairs, according to the regulations, moderate meetings. According to Klim Izuzov, a long-standing member of the regional and federal patient councils, moderation is a special skill, which requires knowledge of psychology and recognized authority of the chair among the members. Apart from chairs, all councils have secretaries. As shared by three patient councils’ secretaries, their position entails communication with the state institution and bookkeeping of various documentation like protocols. All observed councils, federal and regional alike, consisted of ten to twenty members. Many councils, in line with the methodological handbooks created by the Andronov Railways think tank and Translation Bureau federal-level PO, have working groups devoted to specific pre-identified topics. All observed meeting agendas were created by working groups or individual council members suggesting topics for discussion, albeit approval of chairs and state institutions was always needed. Some topics at the observed meetings included ensuring mechanisms for distributing free lunches suitable for high school students with celiac disease in Syznovo region; covid-19 effects on in-patient treatment of people with multiple sclerosis in Bakluzhino; and, a unified public council ethical code approval by the federal Roszdravnadzor public council. Experts, like heads of hospitals, and state officials, like Ministerial specialists were attending all meetings and giving their professional opinion at all topics relevant to their expertise. Additionally, heads or deputies of the state institution, to which councils are attached, regularly joined meetings. Their presence, according to several research participants, has been giving additional importance to otherwise non-binding recommendations of the councils.

The work of all consultative bodies, regardless of their level of independence and activity in policy-making, is non-binding, and the implementation of proposals by public and patient councils depends on the goodwill of state officials, such as governors and heads of the regional Ministries of Health. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic was used by many state institutions as an excuse for ignoring, postponing, or cancelling meetings of consultative bodies, a practice referred to as “the ice age of COVID-19” in the interviews. This indicates that despite legislative developments, consultative spaces are still not necessarily nourished and supported by governmental actors in their channelling of public and patient participation. It also indicates that since state officials often see the activities of consultative bodies as a headache and, possibly, a threat, these bodies do provide some opportunity for the public and patients to impact governance rather than being just mock institutions.

Even the most independent consultative bodies, which provide POs with opportunities for being listened to, taken into account, and, eventually, impacting healthcare governance, function within the framework developed by the state administration. Hence, to adapt patient experiential knowledge to what is considered acceptable and credible by state officials, POs have to perform formatting work.

Performing formatting work

The work of Russian POs includes everyday consultations, advice, and legal assistance to patients; writing complaints to the healthcare providing organisations and relevant health state institutions such as regional MoHs; data gathering and analysis of patients’ needs; raising awareness of the identified problems and finding supporters to the proposed solutions among public health experts, medical professionals, and other actors; various education events such as patient schools and trainings for patient council chairs; organisation of meetings, such as annual conferences, fora, and ad hoc roundtables on specific topics; conducting social projects; and patient community building and maintenance, including preparation, publishing, and dissemination of methodological materials containing “social technologies” of how to make “systemic” improvements in healthcare.

Most of the activities listed involve formatting work that transforms patient experiential knowledge into forms recognisable for state officials and, by association, for medical doctors and scientists who almost like patients, need to be cognizant of the state actors’ entrenched modes of acting and thinking. That is, formatting patient knowledge does not constitute a separate stage or a kind of POs’ activities, rather it infuses almost all of what they do. Before delineating how formatting takes place and what the resulting formats look like, we briefly turn here to the issue of what it is that is being formatted. The definition adopted in this article derives from our fieldwork and is formulated in a dialogue with scholarship on patient experiential knowledge. Patient experiential knowledge that Russian POs format stems from personal experience of living with a specific health condition(s) and of interacting with the healthcare system. In her seminal work on experiential knowledge in health, Borkman (1976) characterised such knowledge as individual, pragmatic, holistic and applicable to the ‘here and now’.

We observed these characteristics in our fieldwork too: patient experiential knowledge POs formatted was more individual than collective; more pragmatic in terms of being tied to practical outcomes perceived by an individual going through an experience rather than to a theoretical comprehension of larger-scale processes; more holistic due to being concerned with phenomena experienced in their totality rather than segmented; and more related to here-and-now action rather than to long term systematic accumulation of knowledge. One example of an experiential knowledge was mentioned during the online meeting held in February 2022 by the federal-level leaders of an organisation uniting patients with a severe neurological disease. A regional chapter representative mentioned that relatives of a patient complained that this patient was not granted a disability status, which is a condition for the state-funded palliative care provision. From the everyday life point of view, the patient was bound to the bed and her condition was deteriorating, with her already being immobile and starting to lose the ability to speak, yet still being able to swallow and, thus, eat. The patient was deeply aware of her severe limitations in movements, acutely experienced being confined to a bed in an apartment lacking needed supportive devices, lived daily with knowing that her time was coming to an end, as well with rising tensions between herself and her exhausted relative carers. However, none of this experiential knowledge mattered for receiving a disability status. The status, instead, depended on the state of a simple bodily function—her ability to swallow, the existence of which prevented granting of the disability status according to the ministerial order 345/372 in force at the time. It became the job of the organization to do the work of formatting this knowledge to make it acceptable and actionable for the state decision-makers.

After publication of Borkman’s work, other scholars suggested understanding experiential knowledge characteristics and their opposites as parts of continua rather than dichotomies; in this paper we follow this approach. Indeed, for example, a research participant complained that she and her fellow organisation members were unable to receive treatment for their children with a rare disease for months due to COVID-19 pandemic. The experience meant personal worries, anxiety, and witnessing the suffering of their kids, but it was also to some extent a collective experience, as research participant’s stories were shared by others and were interconnected with wider social processes, such as COVID-19 pandemic and linked logistical disruptions in deliveries of drugs to the regions. Still, experiential knowledge shared by research participants was more individual because such sharing turned out to be limited and knowledge itself remained largely implicit and not readily “transferable”, a feature of patient experiential knowledge noted by Castro et al. (2018). Also, patient experiential knowledge does not necessarily have to be viewed as opposite of more abstract scientific knowledge. Some patients might seek scientific knowledge pertinent to their condition, then internalised scientific knowledge may structure their experientially gained knowledge, “hybridising” it, as Halloy et al. (2023) note. But still, experiential patient knowledge is inextricably tied to individual experiences of what is possible and not in life with a specific health condition in a specific context even if these experiences were gained in the presence of non-experiential knowledge developed, for instance through “discursive reasoning, observation, or reflection on information provided by others” (Borkman 1976, p. 446).

Below we delineate how this knowledge is made by the POs to fit preferred ways of working and thinking of the state administration actors. In practice, POs’ formatting work comprises creating administratively and, to a certain extent, medically and scientifically, acceptable patient knowledge out of colloquial complaints, conflicts, and everyday challenges experienced by patients and delivering this knowledge to state and credentialed expert actors in the process of interaction. In both creating and delivering knowledge, three foci of formatting work are analytically distinguishable: language, practice, and materiality. Below, we discuss each of these foci of formatting work in detail.

Formatting language

POs access and accumulate patients’ experiential knowledge in different ways. For instance, PO management frequently consults the PO members in-person, by phone or via messengers. Most research participants shared that their personal mobile phone numbers were available to all members of their POs and they received from several to dozens of calls every day from PO members and also from other patients coming in touch with the PO for the first time. Our interviews with PO management members were interrupted several times by calls from patients, who would ask for advice. POs usually have a strong online presence in social media such as VKontakte. Patients may send messages and occasionally post on POs social media pages and channels. Via these routes research participants—heads or employees of the sixteen different POs—learn about individual patients’ experiences of being sick and receiving healthcare. At this stage patients’ knowledge that stems from these experiences and reaches the POs takes a form of distressed pleas for help, emotional accounts of pain or indifference of hospital personnel, and posts on Facebook.

Research participants spoke critically of the experiential patient knowledge they, thus, come in touch with. They characterised it as unstructured, inconsistent and lacking connection to a wider context of healthcare system operation. They took it upon themselves to format it, transforming daily frustrations, conflicts, and challenges experienced by patients into cases of violation of patient rights or failure of medical professionals to comply with medical standards or “systemic problems” requiring legislative action, understandable by the state administration actors and compatible with their bureaucratic processes.

This formatting work focuses, first, on language. The three most important rules of language formatting can be distinguished. First, it is necessary to use officese or healthcare governance pidgin, that is, medical and scientific professional jargon paired with managerial buzzwords. Russian POs consider it important to command it:

From the very first sentence said, a person will understand whether you really are into the topic if you use appropriate terminology.

– Raisa Zemnova, regional Roszdravnadzor patient council member.

Thus, when bringing experiential patient knowledge forward to make it bear on healthcare governance, POs reformulate what was conveyed to them using healthcare governance pidgin. Notably, PO management themselves do not necessarily rely only on office in their daily communications. For example, during the meetings of patient councils observed, council members were shifting from one way of speaking to another, situationally deciding which one serves better their communicative goals. However, when asked later about observed style of conversation at the council meetings, all research participants would strongly disapprove the use of colloquial language, calling it “unprofessional”, “lack of training”, and “bazaar”. The usage of oficese, according to several interviewed federal-level PO leaders, appears to signal to the state administration actors that those speaking can contribute meaningfully to healthcare governance, can be “efficient” and “productive”, and are also likely to understand how healthcare governance works and, hence, can be expected to refrain from unrealistic or/and irrelevant policy proposals. Thus, patient knowledge reformulated in this language gains a chance of being recognised as credible.

Second, apart from being reformulated with usage of particular terms, patient experiential knowledge gathered by POs also needs to be purified of emotions in order to make it fit with the preferred ways of communication of the state actors:

In communication with state institutions, [it] is really important to avoid emotions.

– Doc. 35, YouTube Video “Non-governmental organisation as an instrument for defending patient rights”, a presentation by Anatoly Luty, regional MoH patient council member

A work of containing emotions is a key component of formatting the patient’s experiential knowledge. Again, POs management may occasionally deviate from the rule of “no emotions”. It is possible to give a “human touch” in presentations at patient council meetings or the meeting with state officials, but for tactical reasons only and only upon being sure that a specific state official will be receptive to it, which is rare, as many research participants claimed in the interviews. Otherwise, authors of methodological handbooks for POs and trainers who educate PO members on how to communicate with the state strongly advise avoiding emotions, especially conflictual strong language. One has “to be in a professional position” when communicating with state officials, as put by hired coaches at the regular training based in popular psychology for PO workers, whereas conflictual language appears to signal otherwise. According to almost all interviewed research participants, cold-blooded and emotionless way of conveying patient knowledge makes it harder for state actors to dismiss patient knowledge as inappropriate for governance, as it fits the logic of the state administration itself.

Lastly, formatting patient experiential knowledge to follow conventions of language acceptable for the state administration has to align with a wider effort repeatedly mentioned in the interviews: the effort of being “constructive” (a term often used by the research participants and PO documents). Being constructive means here having a general predisposition for partnership and collaboration with state actors and credentialed experts, expressed in the way of speaking. For example, a report about how NGOs can best participate in health governance in Russia describes its audience as one big collaborating collective that involves state actors, medical professionals, patients and wider public:

The report serves heads and specialist of state health governing bodies, federal and regional members of parliament, health professional community, patients and a wider public, i.e. to everyone interested in improving healthcare system and social protection in the Russian Federation by involvement of civil resources and management of public control and participation (Sergeeva et al. 2018, p. 4).

Constructive patients do not aim to revolutionise or abandon the healthcare system and, by proxy, the existing political regime. Instead, such patients accept health care as it is, with some glitches to be fixed, and see state actors as well-intentioned professionals. This constructive attitude towards the state actors was summed up by a head of one large PO in the following way:

No one [in state administration] wants to harm people intentionally.

- Alexander Koropanov, federal PO chair, federal MoH POC member

Expression of patient knowledge in oficese and its purification of emotions serve as signifiers of constructiveness.

Overall, language-focused formatting of patient experiential knowledge done by POs allows to turn a patient’s cursing into a high level of dissatisfaction, emotional account of doctor’s wrongdoing into a dry description of normative acts violated and clinical recommendations ignored, and individual suffering and pain into a healthcare provision inefficiency with potential for “social instability” which would lower support to the political regime. Language-focused formatting work, thus, excludes emotion-based formats of patient participation in healthcare governance, such as expressions of outrage or suffering, and thoroughly critical formats of patient participation that would question the legitimacy of the existing healthcare governance.

Formatting practices

Using the right language is important to be understood and accepted by state decision-making actors. However, it might not be enough to ensure inclusion of patient experiential knowledge into healthcare governance. After all, healthcare governance is not just about speaking but also about doing things in a particular way. Thus, POs’ work of formatting patient knowledge also entails reliance on specific practices when interacting with patients and state officials. What POs do was aptly summarised in the methodological handbook by the Translation Bureau on how to run PC:

[POs] prevent conflicts by organising a dialogue.

– Doc 44 ‘NGO Technologies of Public Control’, p. 7.

The organisation of dialogue in the quote refers not to dialogue itself but to a work of making dialogue possible. In terms of practices, formatting patient knowledge involves several broad elements, each of which also supports creation of this possibility.

First, it involves quantifying patients’ experiences and aggregating them in such a way as to strip them of everything individual, personal, and tied to particular situations. When attempting to include experiential patient knowledge into healthcare governance, POs transform experiences shared with them into numerical data. POs prepare, send out, collect, analyse, and interpret surveys to produce such data on the topics and issues that were brought to their attention. Surveys could be large-scale, such as the all-Russia survey for parents of children with disabilities, but also small-scale, such as local ad hoc surveys of PO members on social media about the availability of specific drugs. Irrespectively of their scale, surveys allow POs claim, for instance, that a certain percentage of patients living with a certain health condition face a particular challenge when attempting to receive medical care. Upon such quantification, patient experiential knowledge ceases to be connected to specific individuals and their circumstances. Instead, it becomes tied to widely experienced—“systemic” to use a term the POs rely on—problems in healthcare system functioning. Such systemic problems can be then brought to the attention of the state actors without a high risk of being dismissed as emotions of one overly sensitive patient or an outcome of unfortunate circumstances that uniquely came together in one specific case.

Second, apart from being quantified and aggregated, patient experiential knowledge is also framed by the POs in terms of existing legislation. POs’ management reviews normative acts, existing policies, medical standards and clinical recommendations. They also continuously perform routine monitoring of the situation in healthcare, regularly checking for the updates in legislation and making regular requests to the regional ministries and pharmacy warehouses to ensure drug availability. Thus, formatting of experiential patient knowledge done by POs in order to make this knowledge fit for being included in healthcare governance, results in claims being formulated in a particular way as highlighted by one of the research participants:

Your opinion should not be “I think so”, it should be based on normative acts, which say so, or so.

- Arina Kassova, regional PO leader, POC member

Formatted this way patient experiential knowledge may more or less seamlessly be plugged into established practices of healthcare governance.

Third, formatting patient knowledge involves presenting it in a specific way. It is mostly presented in the form of a report (e.g. ‘Accessibility of Innovative Drugs’ by the analytical centre ‘Sotsialnaya Mehanika’ 2022), of a policy proposal (a letter to the federal MoH Drug Supply Department N25-03(м), Matvievskaya 2021), of an official letters (Vlasov and Zhulev 2020), or of a complaint (Golovin 2018). Done voluntarily and before any request by state institutions, it is a sort of anticipatory work that involves aligning with the work practices and conventions of communication common among the state actors before expected interaction (Barley 2015). Such presentations often contain some sort of endorsement of credentialed experts. While scientists and medical professionals also find themselves subordinated to the state administration, listing their approval of POs’ reading of a situation and a proposed solution is often practised as one of the measures to increase the chances of patient experiential knowledge being taken on board in healthcare governance, albeit certainly not the most important measure.

Lastly, in a somewhat larger scale fashion, POs format patient experiential knowledge by articulating it together with those of more powerful healthcare actors, as formulated by one research participant:

Third sector workers today are a mediator between two opinions. They [experts and state institutions] search for a third opinion for a balance (…) [They] cannot agree. What is needed then? A third person. [They] want to achieve a result—a decision. A third opinion [from POs] comes, which takes part of [first] opinion, part of [another] opinion, and makes a compromise decision.

- Anatoly Kudesov, the federal MoH patient council member, regional patient council member

Such articulation of patient knowledge together with knowledge of more powerful actors is enabled by POs positioning themselves as a neutral third party and mediating between other actors. The POs’ mediatory position builds upon state administration and credentialed experts’ knowledge systems and preferred ways of working but also adds patient perspectives to it. Therefore, the work of being a mediator means not only being in-between actors but also adding and transforming the knowledge involved itself (Sayes 2014, p. 138).

Overall, formatting work is constituted but also constitutive of the hierarchy of knowledge. All the delineated practices of formatting patient knowledge make dialogue between different actors in healthcare governance possible but also maintain and solidify the knowledge hierarchy in which patient knowledge remains at the bottom, as illustrated by the following quote:

The patient knows the problem: “I was not given a drug; I was refused medical assistance”. However, the patient does not know, in most cases, why it is so. To solve a patient’s problem, we need to look into the situation and do serious preparatory work. We need to get a grip on underlying reasons because it will help us rightly formulate our demands, identify the cause of the problem, and know to whom to write a complaint: a minister, head doctor, head specialist, or someone else.

- Ivan Korepanov, Translation Bureau chair, federal MoH patient council member

The inclusion of patient knowledge in healthcare governance is then done in practice via the means of fitting patients’ experiential knowledge into formats acceptable by state actors. These formats are aggregated and quantified, rely on framings provided by the existing legislation, assume a form of a report, a policy proposal or a complaint, and articulate experiential patient knowledge together with knowledge and perspectives of more powerful actors. Paradoxically, what enables the inclusion of patient knowledge simultaneously works to preserve its lesser status.

Formatting materiality

Formatting practices mentioned in the previous section are being performed and enacted with the involvement of material objects. A shift from everyday patient experiences to knowledge recognisable by state officials is embedded in a change in materiality, which we understand not only as “tangible stuff” but also as “practical instantiation of theoretical ideas” (Leonardi 2010) and the “exchange or manipulation of material things” (Pinch, 2008 in Leonardi 2010). In other words, materiality is not just a sum of objects but also interactions and effects emerging from the existence of ideas, concepts, and imagination. In the case of patient knowledge formatting, we identified three forms of materiality bearing on formatting work: a substitution of messy everyday patient experiences with orderly and somewhat structured artefacts of healthcare governance; artefacts embodying and representing formatting itself; and material components of knowledge formatting infrastructure.

First, some artefacts signify a substitution of everyday patient experiences in the context of healthcare provision with more refined and orderly artefacts of healthcare governance. Suits worn at the public council meeting differ from both the patient’s home t-shirt and what they wear to a social event organised for the PO members. Suit, mentioned as a commonly agreed norm in the interviews, represents a state administration-acceptable official interaction. In turn, teapots and cakes from a local supermarket are signifiers of a local self-help initiative by patients:

They [patients] initially come here [public reception event] and think of something official, [expect to meet] a stereotypical thick, bald state official, an evil one, who will try to evade the answer with some formal response. [Patient] enters the room [and see] we are all ordinary people, sitting next to the table, with tea and cakes. They say, “Oh, excuse me, are you having an event here?” “Yes, we are waiting for you. Come, sit down, please” “Me? “Yes, we are waiting for you. Here’s your tea, here’s your coffee”.

– Anatoly Kudesov, the federal MoH patient council member, regional patient council member

Kudesov described a setting for individual complaint collection and for working with patients dissatisfied with treatment. He pointed to a contrast between expectations about the event (public reception, obschestvennaya priemnaya) and actual arrangements. He went on to explain how patients get ready to interact with state institutions (wearing a tie, rehearsal of a speech) and how POs help them in doing this work. The materiality of patients and state administrations is incompatible without adjustments, and these are patient organisations that bridge the two with formatting work, including shifting spaces and using artefacts appropriate for state administration when representing patients’ worries.

Second, some artefacts are being employed specifically to help format knowledge. Two illustrative examples of such artefacts are Google Surveys and complaint templates. A patient survey interface on Google Surveys is an artefact attributable neither to state administration nor to everyday patient experiences. It is an element of the formatting work performed by POs to quantify and aggregate patient experiential knowledge as discussed in the previous section or to test opinions about policy proposals developed by PO management. It includes both attitude measurements and specific questions about the problems patients face in their daily lives. As for complaint templates available to patients on some POs’ websites developed to inform patients about their rights and ways to defend them, they:

…Discuss typical situations that patients encounter and how to approach them. With links to legislation and document templates. This is a “living” document that changes all the time because regulations change: COVID is there too. I think the 15th edition of COVID orders. Laws change all the time. Every year, the programme of state guarantees [change]. We change links all the time and add some new situations.

– Domna Domna, regional patient council member

Templates described by Domna Domna are ready-to-use tools for translating patient worries into something solvable by medical institutions or state officials. What templates do is a “substantialisation” or making negative experiences and associated worries into a written official document, satisfying language, framing and form expectations of the state institutions.

A final aspect of materiality involved in formatting work is the patient knowledge formatting infrastructure [see Voß et al. (2022) for knowledge infrastructure conceptualisation]. Significant part of work of POs that aim to ensure involvement of patient knowledge in healthcare governance, is devoted to maintenance and spread of formatting skills among patient community members. They also educate patients via “patient schools”, where medical doctors teach patients about their health condition, and training, where patients and new PO members are being taught business communication, writing grant applications, mediation, state administration, and policy-making. Apart from discourses and practices, such infrastructuring interactions involve material components, such as artefacts necessary for educational events like chairs, flipcharts, and video recording, or methodological handbooks developed by the larger POs within the framework of social projects funded by the federal ministries. The latter documents are project reports and compilations of the best practices created by POs and their allied think tanks. These handbooks usually present results of major cross-regional surveys, with the theoretical discussion section substituted by practical recommendations and advice for POs on what to do in order to be recognised as relevant partners by state institutions and credentialed experts and ensure involvement of patient knowledge in healthcare governance. Rules and guidance on formatting of the patient knowledge according to conventions delineated above is a typical part of such handbooks:

Based on identified practices, expert experience and document analysis, we have built a The POC Model. The Model includes Evaluation scale (criteria and performance indicators), as well as documents, algorithms and recommendations for POC work (Vlasov et al. 2016, p. 48).

To summarise, patient experiences are usually detached from state administration practices and knowledge. Only PO representatives and formatted versions of patient knowledge reach conference halls and state officials’ offices and zoom sessions. Hence, spaces, artefacts, and ideas about credible knowledge are constitutive and constitute formatting work. Moreover, formatting work knowledge infrastructure facilitates a common vision of what stands for consultative spaces like public councils, with formatting work presented as necessary for successful participation in healthcare governance. As a result, patient community educational events, by normatively differentiating between acceptable and unacceptable forms of participation, become a driving force in the channelling of patient participation and, correspondingly, reinforce knowledge system hierarchies.

Discussion

In this article, we showed how POs work to format patient experiential knowledge to make it recognisable and acceptable to other, more powerful actors in healthcare governance in Russia. Such formatting is more than translating from the colloquial language of laypeople into the professional slang of state officials and credentialed experts. Instead, it is a thorough work that proceeds through focusing on language, practices, and materiality, allowing the inclusion of patient knowledge but also maintaining its place at the bottom of the healthcare governance hierarchy of knowledge systems.

Patient experiential knowledge that is being formatted is largely individual, tacit, pragmatic and connected to here-and-now. To make it compatible with the work practices and conventions of the state administration and, thus, for inclusion in healthcare governance in Russia, POs translate it in oficese, purify of emotions, infuse with “constructiveness”, quantify and strip of connections to specific persons with their specific circumstances, frame in terms of existing legislation, and articulate it together with knowledge and perspectives of more powerful actors. All these moves together constitute formatting work that is being aided by the material artefacts directly employed in formatting, such as Google Surveys, and involved in presenting formatted patient knowledge such as suits and ties. As a result, POs produce reports, policy proposals and complaints content, form and tone of which allow them to be seamlessly plugged into state administration apparatus operation. Some elements of this patient knowledge formatting work, for example emphasis on quantification, can certainly be encountered outside of the studied setting. Authoritarian specificity of the process presented here, though, lies in the necessity of all the mentioned elements of the formatting work to be implemented together in order for patient knowledge to be considered by the state administration actors. These are state administration actors that dominate the healthcare governance landscape in Russia with knowledge of patients, medical professionals and scientists being subordinated to their preferred ways of working and thinking. Subordination is not uniform since medical professionals and scientists do appear to have more weight in healthcare governance than patients. Nonetheless, state actors occupy a position of dominance over them all.

Another authoritarian specificity is that despite developing ways to insert patient knowledge into healthcare governance, Russian POs operate in such settings, where rules, however established, are subject to quick and whimsical changes. No matter how good POs are in formatting, credentialed experts and state officials might still be reluctant to accept the credibility of patient experts. For instance, the federal MoH representatives are ready to listen to POs speaking at public councils (non-binding consultative spaces) but can be critical of POs’ involvement in other circumstances, such as binding decision-making. Moreover, where there is a strong desire to avoid the involvement of POs, state actors might even use the formatting expertise of the largest POs that tend to be successful in their efforts as a pretext to question their credibility. This was the case when one PO was refused a state grant, as shared by one research participant, on the pretext that the submitted application was “too professional” and hence written by people “too detached from lay patients” and their needs.

Notably, a perceived linkage between formatting expertise and detachment from the lay patients fits well with the critical debate over third sector professionalization (Holavins 2020; Krause 2014). Organization of work in projects, aforementioned ‘quantification’, the use of officese, and the organizational capacity-building of smaller POs through the knowledge infrastructure by the federal-level POs can be interpreted as an indication of the qua-professional status of the patient experts and their organizations. Similarly, a claimed mediator role of POs, organization of expert meetings and a distinction between PO employees and members (beneficiaries) are elements of patients’ self-help groups’ transformation into legal entities with financial and administrative needs. The shift in question, however, is not just an organizational process, as it is defined by the third sector professionalization literature (Jalali 2013; Alvarez 2009). Rather a making of qua-professional patient experts is a change in everyday practices and a shift between different knowledge systems.

In this article, we also highlighted that larger POs do the work of articulating and promoting the best formatting practices via educational and community-building activities. These activities facilitate the emergence of a knowledge infrastructure (Voß et al. 2022) of patient participation in Russia. Knowledge infrastructure, according to Voss and co-authors who analysed standardisation of deliberation practices, means practices that “enable and constrain the circulation of know-how, configure processes of mutual learning, shape the translocal innovation process” (Voß et al. 2022, p. 106). It involves the emergence of formalised expertise within a particular community of practice. In our case, we speak of the infrastructure of patient participation, and the expertise created is that of patient knowledge formatting. As a result of the emergence of this knowledge infrastructure, certain patient participation practices, such as street protests or emotional breakdowns at meetings with state officials, become further marginalised, whereas writing policy recommendations and getting them approved by the research institute’s leadership is nourished and praised. Consequently, the formatting expertise becomes, as with other technologies, “both engine and barrier for change” (Star and Ruhleder 1996, p. 112 in Voß et al. 2022, p. 121), paving the way for channelling patient participation along particular routes. In other words, patient knowledge formatting infrastructure becomes a vehicle for channelling patient participation beyond conventional consultative authoritarianism coercion. Notably, formatting work and, hence, channelling patient participation is not a top-down process. It is a distributed channelling, as it is distributed among healthcare governance actors, including the POs themselves, and animated by the dominant perspectives on credibility.

As a key element of credibility and, thus, paving the way to healthcare governance, formatting work has become central to the identity and practice of many POs in Russia. Therefore, in the channelling of patient participation in Russia, only “objective” and “constructive” patients come to be involved through the media of reports distributed in consultative spaces; it is interactive and distributed, produced by POs’ formatting work, and maintained by the knowledge infrastructure of patient participation. Patients who are thoroughly critical of the operation and governance of the healthcare system, who are not prepared present themselves as apolitical at least or supportive of the current regime at best, and who find value and validity in personal experiences, thus, become excluded from participation.

Conclusion

Patient participation is increasingly seen by governmental decision-makers across the globe as relevant and necessary for healthcare governance due to consumerist, efficiency, and democratic considerations (Olsson et al. 2020, p. 1454). Nevertheless, in practice, patient participation in healthcare governance is often challenged, not least due to the low credibility of experiential knowledge among decision-makers. The article showed how Russian POs work to overcome these challenges. Namely, they format patient knowledge, focusing on language, practices, and materiality to make it recognisable and acceptable by state healthcare governance actors. POs also develop and maintain an infrastructure of patient knowledge formatting expertise, defining the kinds of patient participation to be preferred and to be avoided. This knowledge infrastructure facilitates channelling of patient participation along a particular route that involves usage of professional language, reliance on emotionless practices, and demonstration of constructiveness. It is more productive to understand the emergence and maintenance of this knowledge infrastructure not as an act of self-censorship but as an ongoing co-production process performed by the health governing actors’ networks. Thus, its main outcome—channelling of patient participation—is distributed and not necessarily forced unilaterally. At the same time, further research is needed on the limits to formatting work, what is achievable, and what remains out of reach for POs under different circumstances, as well as comparative research that takes into account alternative, less collaborative, and more subversive PO practices that are still present in Russia.

Data availability

Authors decided not to share data for ethical reasons, specifically due to the legal and physical risks for the Russian research participants associated with participation in the foreign project.

References

Alvarez, S.E. 2009. Beyond NGO-ization?: Reflections from Latin America. Development 52 (2): 175–184.

Barley, S.R. 2015. Why the internet makes buying a car less loathsome: How technologies change role relations. Academy of Management Discoveries 1 (1): 535.

Borkman, T. 1976. Experiential knowledge: A new concept for the analysis of self-help groups. Social Service Review 50 (3): 445–456.

Callon, M., P. Lascoumes, and Y. Barthe. 2011. Acting in an uncertain world: An essay on technical democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Callon, M., and V. Rabeharisoa. 2003. Research “in the wild” and the shaping of new social identities. Technology in Society 25 (2): 193–204.

Caron-Flinterman, J.F., J.E. Broerse, and J.F. Bunders. 2005. The experiential knowledge of patients: A new resource for biomedical research? Social Science & Medicine 60 (11): 2575–2584.

Castro, E.M., T. Van Regenmortel, W. Sermeus, and K. Vanhaecht. 2018. Patients’ experiential knowledge and expertise in health care: A hybrid concept analysis. Social Theory & Health 17 (3): 307–330.

Collins, H.M., & Evans, R. (2002). The third wave of science studies: Studies of expertise and experience. Social Studies of Science, 32(2), 235–296.

Epstein, S. 1996. Impure science: AIDS, activism, and the politics of knowledge, vol. 7. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gibson, A., Britten, N., & Lynch, J. (2012). Theoretical directions for an emancipatory concept of patient and public involvement. Health, 16(5), 531–547.

Golovin, A. 2018. Letter N511. Saint Petersburg: OOOIBRS. https://oooibrs.ru/media/449989/v-prokuraturu-sankt-peterburga-protest.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Halloy, A., E. Simon, and F. Hejoaka. 2023. Defining patient’s experiential knowledge: Who, what and how patients know. A narrative critical review. Sociology of Health & Illness 45 (2): 405–422.

Holavins, A. 2020. Little red riding hood and a critique of project thinking among NGOs. The Journal of Social Policy Studies 18 (3): 461–474.

Hoļavins, A., and O. Zvonareva. 2022. The expertise of patient organisations: making patients’ voices heard. Zhurnal issledovanii sotsialnoi politiki. 20 (2): 335–346.

Irwin, A. 2002 (1994). Citizen science: A study of people, expertise and sustainable development. London: Routledge.

Jalali, R. 2013. Financing empowerment? How foreign aid to southern NGOs and social movements undermines grass-roots mobilization. Sociology Compass 7 (1): 55–73.

Jasanoff, S. 2005. Technologies of humility: Citizen participation in governing science. In Wozu Experten? 370–389. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kerr, A., S. Cunningham-Burley, and R. Tutton. 2007. Shifting subject positions: Experts and lay people in public dialogue. Social Studies of Science 37 (3): 385–411.

Kirkland, A. 2012. Credibility battles in the autism litigation. Social Studies of Science 42 (2): 237–261.

Krause, M. 2014. The good project: Humanitarian relief NGOs and the fragmentation of reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Laurent, B. 2017. Democratic experiments: Problematizing nanotechnology and democracy in Europe and the United States. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Leonardi, P.M. 2010. Digital materiality? How artifacts without matter, matter. First Monday peer-reviewed online journal website. https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3036/2567. Accessed 7 Dec 2023.

Martin, G.P. 2008a. ‘Ordinary people only’: Knowledge, representativeness, and the publics of public participation in healthcare. Sociology of Health & Illness 30 (1): 35–54.

Martin, G.P. 2008b. Representativeness, legitimacy and power in public involvement in health-service management. Social Science & Medicine 67 (11): 1757–1765.

Matvievskaya, O. 2021. Letter 25-03(m). Moscow: OOOIBRS. Russian Multiple Sclerosis Society official website, https://oooibrs.ru/media/455382/25032021-direktoru-departament-lekarstvennogo-obespecheniya-em-astapenko.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Mol, A. 2008. The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice. London: Routledge.

Olsson, A.B.S., A. Strøm, M. Haaland-Øverby, K. Fredriksen, and U. Stenberg. 2020. How can we describe impact of adult patient participation in health-service development? A scoping review. Patient Education and Counselling 103 (8): 1453–1466.

O’Shea, A., M. Chambers, and A. Boaz. 2017. Whose voices? Patient and public involvement in clinical commissioning. Health Expectations 20 (3): 484–494.

Pols, J. 2005. Enacting appreciations: Beyond the patient perspective. Health Care Analysis 13 (3): 203–221.

Popay, J., S. Bennett, C. Thomas, G. Williams, A. Gatrell, and L. Bostock. 2003. Beyond ‘beer, fags, egg and chips’? Exploring lay understandings of social inequalities in health. Sociology of Health & Illness 25 (1): 1–23.

Rabeharisoa, V., T. Moreira, and M. Akrich. 2014. Evidence-based activism: Patients’, users’ and activists’ groups in knowledge society. BioSocieties 9 (2): 111–128.

Sayes, E. 2014. Actor-Network Theory and methodology: Just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency? Social Studies of Science 44 (1): 134–149.

Sergeeva, S., M. Churakov, and Ya. Vlasov. 2018. Opisanie tehnologiy organizatsii deyatelnosti [obschestvennogo kontrolya i] obschestvennogo soveta pri organah zdravoohraneniya. Moscow: OOOIBRS. All-Russian Patient Union official website, https://vspru.ru/media/548226/tehnologii-os_2018.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Sotsialnaya Mehanika. 2022. Dostupnost innovatsionnyh preparatov—2022. Moscow: Sotsialnaya Mehanika. All-Russia Patient Union official website. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Star, S.L., and K. Ruhleder. 1996. Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces. Information Systems Research 7 (1): 111–134.

Stewart, E. 2016. Publics and their health systems: Rethinking participation. Berlin: Springer.

Thompson, J., P. Bissell, C. Cooper, C.J. Armitage, and R. Barber. 2012. Credibility and the ‘professionalized’ lay expert: Reflections on the dilemmas and opportunities of public involvement in health research. Health 16 (6): 602–618.

Truex, R. 2017. Consultative authoritarianism and its limits. Comparative Political Studies 50 (3): 329–361.

Vlasov, Ya., and Yu. Zhulev. 2020. Letter ‘VSP-01/263’. Moscow: VSP. All-Russia Patient Union official website, https://vspru.ru/media/1210339/vsp_pismo_mishustinu-po-perechnyu-zhnvlp-na-2021-god.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Vlasov, Ya., Yu. Zhulev, I. Myasnikova, and M. Churakov. 2016. Healthcare public control. Methodological handbook. Issue N3. Moscow: VSP. Sotsialnaya mehanika analytical centre official website, http://www.socmech.ru/files/library/biblioteka2020/4-dokumenty/3metodicheskij-sbornik-obshhestvenyj-kontrol-zdravoohranenija-2017.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Voß, J.P., J. Schritt, and V. Sayman. 2022. Politics at a distance: Infrastructuring knowledge flows for democratic innovation. Social Studies of Science 52 (1): 106–126.

Wynne, B., and M. Lynch. 2015. Science and technology studies: Experts and expertise. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2nd ed., ed. J.D. Wright, 206–211. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Zhulev, Yu. 2015. Issledovanie luchshih praktik sotsialno orientirovannyh nekommercheskih organizatsiy. Moscow: VSP.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript is comprised of original material that is not under review elsewhere, and the study on which the research is based has been subject to appropriate ethical review (Maastricht University Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences Research Ethical Committee decision FHML-REC/2021/109; Saint Petersburg Association of Sociologists—SPAS decision 03.12.2021 №_1). Authors do not have any competing interests in the research detailed in the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No 948073). This article reflects only the authors’ views and the Agency and the Commission are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikulkin, V., Zvonareva, O. Formatting patient knowledge and channelling participation: how patient organisations work under authoritarianism. BioSocieties 19, 526–547 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-023-00316-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-023-00316-9