Abstract

Heibaika (Mandarin for black-and-white cards) are tools that Taiwanese parents use for infants below 3 months old. These cards are claimed to stimulate vision and enhance the brain. Although the scientific efficacy of heibaika is questionable, the wide circulation of these cards illustrates the ways some try to urge laypeople to imagine and picture the infant brain. Thus, the use of heibaika constitutes a good example of neuroparenting and neuroculture, where flourishing neuroscience transforms the parenting culture. In the present study, multiple methodologies are applied, and the emergence of heibaika is identified as a twenty-first century phenomenon popularised by online forums and postpartum care centres, among many other channels. Heibaika are contextualised in the globalisation of neuroparenting through translation since the 1990s and the rising anxiety of contemporary Taiwanese parents. Through interview analysis, parents are classified into believers, sceptics, and cautious experimenters. Their anticipations and worries are further elaborated. The paper concludes by highlighting its three major contributions: the importance of studying lay neuroscience as a way to rethink and problematise the boundary between science and culture, the enrichment of the concept of neuroparenting, and the emphasis on the dimension of globalisation and knowledge transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: lay neuroscience, neuroparenting, and neuroculture

Neuroscience has recently become a powerful scientific discipline that transforms the way we see ourselves, the society and the future. The advent of the brain era and becoming a cerebral subject are two sides of a coin (Ortega and Vidal 2011). Consequently, the notion of neuroculture has been raised as a conceptual umbrella that covers a wide variety of phenomena on the impact of burgeoning neuroscience on contemporary society (Frazzetto and Anker 2009; Ortega and Vidal 2011; Rolls 2012; Franks 2010). Personal and collective effects of psychopharmaceuticals, visualisation of human consciousness with the aid of neuroimaging, analysis of economic and decision-making behaviours through neuroscience, and even aesthetics informed by the understanding of the human brain are all grouped under this term (Frazzetto and Anker 2009).

However, the majority of existing studies on neuroculture have focused on the transformative effects and potentials of cutting-edge neuroscience in the laboratory (i.e. lab neuroscience). For instance, scholars have argued that neuroimaging technologies remake public conceptualisation of personhood and, in juridical settings, personal responsibility and culpability (Dumit 2004; Racine et al. 2010). Moreover, although some scholars have questioned that the loss of autonomy is the rule among people addicted to certain drugs, the widespread neuroscientific model of addiction claims that the addicts’ brains are ‘hijacked’ by the drugs they use (Levy 2011). In these cases, lab neuroscience is often portrayed as a game changer and defining device that can modify, if not overthrow, old thinking and practices (Racine et al. 2005, 2006; Johnson 2004). However, neuroscience ‘in the public sphere’ (O’Connor et al. 2012) or ‘in the public eye’ (Racine et al. 2005) is a research topic that has been minimally explored. Existing research on this topic has also often limited the scope to the analysis of social representations, including frequency or themes of neuroscience and neurotechnology (e.g., functional MRI) as featured in newspapers. Therefore, the knowledge on and practices related to the nervous system that circulate among lay people (i.e., lay neuroscience) should be studied.

A major feature of lay neuroscience is its ambiguous and amorphous statements, which may appear as hearsay or gossip. In this study, the word ‘lay’ has twofold meanings. The first meaning refers to the people who act on the statements, whereas the second meaning refers to the format or content of the ‘neuroscience’ therein. Thus, lay neuroscience highlights the mundane practices based on neuro-knowledge that is not necessarily professionally recognised but remains widespread and influential. The variegated manifestations of lay neuroscience imply that neuroculture can be conceptualised and understood in more than one way. Accordingly, the current study shows that neuroculture can be understood by focusing on a domain of neuroparenting where science and culture merge to the extent of indistinction.

Macvarish (2016) addresses neuroparenting as a concept that refers to various phenomena where neuroscience and its experts invade everyday family life, especially parenting. Neuroparenting reveals the ways in which neuroscience as a form of authoritative knowledge has become a new foundation upon which some parents care for their offspring. Parents used to draw from personal knowledge, experience, and age-old wisdom. However, in the fledgling trend of neuroparenting, young brains are portrayed as wondrous and vulnerable, and the development of children and infants is greatly determined by parents’ behaviours. In the transition of ‘parent’ from a noun to a verb (‘parenting’), parent–child relationship is de-naturalised and everyday life is instrumentalised. At the same time, for guarding and guiding the young, a therapeutic state gains legitimacy to enter family life.

Macvarish’s conceptualisation of neuroparenting is based on her observation of the British society and UK policy, and it beautifully depicts a new cultural landscape that has been tremendously informed and transformed by neuroscience. Neuroparenting intensifies and complicates scientific mothering (Apple 1995; Hays 1998; Macvarish 2016) that has long existed and troubled generations of homemakers. It conveys more moral obligations and senses of urgency to parents, especially mothers, because neuroscience indicates that their present actions will lead to their kids’ future personality. The burden of being a parent is never easy, but this burden is now endorsed and verified by science.

A popular example of lay neuroscience and neuroparenting is the Mozart effect (Bangerter and Heath 2004; Beauvais 2015; Jenkins 2001; Shaw 2005), but its social research is alarmingly and intriguingly insufficient. This idea started when Rauscher et al. (1993) published a paper on Nature and claimed that a sonata by Mozart (K448) may temporarily improve listeners’ thinking in patterns. The so-called Mozart effect became an immediate focus of heated debates. Experiments that replicated or extended the Mozart effect to other domains of research have produced mixed results (Rauscher 1999; Chabris 1999; Steele et al. 1999). Although a formal scientific closure is lacking, scientists generally regard this concept in a negative light (Pietschnig et al. 2010; Hammond 2013). Nonetheless, the Mozart effect for a non-scientific audience has continued over time, especially in terms of its association with infant development (Bangerter and Heath 2004; Beauvais 2015). In 1998, Zell Miller, the then Governor of the State of Georgia in the US, demanded that the state should purchase Mozart music CDs for every newborn (Hammond 2013; Bangerter and Heath 2004). The dubious scientificity of the Mozart effect has so far not slowed the sale of such music CDs as gifts for babies.

This study presents another example of lay neuroscience and neuroparenting that circulates among laypeople in Taiwan but appears groundless for scientific professionals, that is, the black-and-white cards that claim to stimulate the vision and brain power of infants below three months old (Fig. 1). These cards are commonly called heibaika (黑白卡) in Mandarin Chinese or, less often, flashcards (shanka; 閃卡). These cards often come in simple geometric shapes (e.g. triangle, target, and heart), everyday objects (e.g. cars, cups, and flowers) and animal silhouettes (e.g. dogs, cats, and cows). These cards are sold as a stand-alone set or together with other brain-stimulating kits. People can easily produce them with a printer if they want to.

According to developmental psychology, coloured vision does not fully develop until three months of age (Schickedanz et al. 1998). Therefore, infants below this age react better to cards with a sharp contrast between black and white (Fantz 1963). However, does this scientific finding lead to the claim that heibaika are good for infants’ brains? Such argument is the point of the controversy.

This study intends to address heibaika as an example of lay neuroscience in Taiwan that is embedded in a global expansion of neuroparenting. First, this study addresses the expansion of heibaika in the past two decades and discusses the contributing factors, including online forums and postpartum care centres (PCCs). Then, the study examines the rise of heibaika vis-à-vis the trend of introducing popular neuroscience books into Taiwan through translations. The translation of popular neuroscience positions heibaika as a manifestation of globalising neuroculture and makes heibaika unique because translation is never faithful. Then, the study addresses the relationship of heibaika and parenting by interviewing parents (mostly mothers) in a PCC where they stayed for weeks after delivery. These parents were asked how they regarded heibaika in particular and what it was like to be a contemporary parent in general. This section addresses neuroparenting in a Taiwanese context. However, unlike Macvarish’s case in the UK, heibaika do not enter family life because of its scientific authority or state intervention. In the final section, the meanings of heibaika are discussed in light of lay neuroscience and neuroparenting. Heibaika are situated in the murky zone between (neuro-)science and (parenting) culture, where parents project their desires and hopes onto their babies. These anticipations are associated with parents’ own social class and anxiety of raising a family in a time of globalisation (also see Lan 2018). In the final section of the paper, the three contributions from studying heibaika as an example of neuroparenting and lay neuroscience are highlighted.

Methodologies and materials

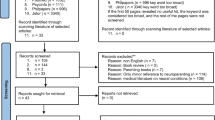

The current study is based on a 2-year research (2015–2017) that applied multiple methodologies, including archival reviews, in-depth interviews, and telephone surveys. This study used keywords, such as black-and-white cards (heibaika) and flashcards, and reviewed various archives and information sources in Taiwan: newspapers, science journals, popular magazines and parenting websites. In addition, I conducted in-depth interviews with 28 people, including 22 parents of newborns (21 mothers and 1 father), 3 PCC staff members, 1 children’s book salesperson, and 2 occupational therapists who applied black-and-white cards for visual rehabilitation. I also contacted several developmental psychologists, paediatric neurologists, cognitive neuroscientists and children’s book editors through e-mail for their professional opinion and additional relevant information. All interviews were transcribed verbatim, coded and analysed with other collected documents via a method suggested by situational analysis (Clarke 2005). Situational analysis is a modified grounded theory, which, in a constructivist stance, focuses on discourses, positions and intersecting social worlds. During the analysis, I produced and compared various maps on social worlds (e.g. scientists, parents, publishers and PCC workers), discourses (e.g. developmental psychology, cognitive neuroscience, parenting advice and folk wisdom) and positions (e.g. believers, sceptics and cautious experimenters) to substantially understand the socio-epistemic situations of heibaika.

To understand the popularity of heibaika among PCCs, a telephone survey was conducted in April 2016, in which all 100 registered PCCs in Taipei City and New Taipei City were inquired whether they offered heibaika for babies. They are the two largest cities in Taiwan where over six million people reside and nearly half of the total number of PCCs in the country (N = 219) are located. The results are presented in the succeeding section.

Heibaika as a twenty-first century phenomenon in Taiwan

To my knowledge, heibaika did not become local in Taiwan until the twenty-first century. Chinese translations of Hana Toban’s White on Black and Black on White (1993) in 2001 are the earliest publications of this kind that can be accessed. As the titles indicate, these books consist of simple shapes, either white or black, in backgrounds of the other colour. An introduction common to such products is presented on their back covers:

Research shows that black and white with their strong contrast are the colours that first attract babies’ attention. This little book contains many common shapes with black and white contrast. It can stimulate babies’ visual perception. No matter how young your baby is, you can watch these cards together and play games by naming the shapes. (Original in Chinese, the author’s translation)

Words, such as ‘attention’, ‘vision’ and ‘stimulation’, abound in the concept of heibaika, but whether its usage precisely corresponds to scientific connotations is uncertain. Developmental psychology is often appropriated to justify the use of these products. However, such appropriation is often subjected to criticism for its distorted interpretation of scientific facts. Although developmental psychology established that infants below 3 months of age tend to be attracted by the high contrast between black and white, critics argue that visual preference does not equal to visual enhancement, not to mention the improvement of the overall brain power (Lin 2014).

Many physiologists have noted and confirmed that the lack of adequate visual stimulation will lead to impaired neural development. The fact seems to support the potential linkage of visual stimulation and neural development, which is thought to be the basis of the claims of heibaika. For example, David Hunter Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel, both Nobel Laureates in 1981, showed the topographic structure of the visual cortex and illustrated how the deprivation of vision during a critical period may lead to irreversible cortical reconstruction (Hubel and Wiesel 1962; Wiesel and Hubel 1965). Their research has paved the way for current visual rehabilitation in cases of amblyopia and cortical blindness (Dundon et al. 2015), where heibaika or similar tools are clinically applied to inflicted children as a therapeutic supplement. The two occupational therapists that I interviewed are engaged in visual rehabilitation. They recognised the usability of heibaika in cases of cortical blindness but asserted that these cards are supplementary, not primary. Even if heibaika are used to rehabilitate challenged children, they knew no existing research that can clarify whether these cards benefit the vision or brains of healthy infants. Moreover, a method is yet to be developed to indicate the adequate extent of visual stimulation.

These unsolved issues compromise the claimed effects of heibaika, but they do not limit heibaika from flourishing in the children’s book section of bookstores and supermarkets. At present, these booklets and card sets are no longer translated works but produced and sold by local publishers at affordable prices (3–5 USD per piece). They are also circulated through other channels. For example, these cards are distributed in promotional activities as complimentary gifts for pregnant women, along with samples of milk powder and diapers. These cards are also easily accessible on the Internet to interested parents.

In an age where the Internet has become a major platform that provides and exchanges information, I found that the source of knowledge of the interviewees on raising a baby has gradually shifted from printed materials, such as books and magazines, to cyberspace. In addition to asking for advice from their experienced peers who have had children, contemporary Taiwanese parents equip themselves with parenting skills through websites of professionals or celebrities who are famous for their knowledge on babies or online forums that collect a vast amount of opinion and experience from other users. Similar phenomena have been reported elsewhere and warrant further research (Santer et al. 2015; Oprescu et al. 2013; Doyle 2013; Lebowitz 2017; Plantin and Daneback 2009).

Among currently available parenting websites in Taiwan, Babyhome (https://www.babyhome.com.tw/) caters the largest number of visitors. SimilarWeb (accessed on 13 February, 2019) is an Israel-based company that monitors Internet use. It indicates that Babyhome ranked seventh in the child health category around the globe, with 92.5% of its visits from Taiwan and 4.95 million visits in the past 6 months. I analysed the messages on Babyhome, where the majority of dialogues on heibaika were posted by parents who generously shared methods of producing cards by themselves or discussed reasons why babies do not respond as expected. Although a series of disputes between heibaika supporters and opponents were found on Pansci (pansci.org, a Taiwanese website that popularises formal science) regarding how the cards work in effect (See Lin 2014), none of the parents on Babyhome questioned whether the cards were scientifically proven. Being scientific or not may be an issue of debate on Pansci, but parents on Babyhome are greatly concerned with observed effects.

In summary, through venues and channels, such as supermarkets, bookstores, online forums, and parenting websites, heibaika have penetrated into the life of parents and expectant parents as an inexpensive and accessible tool. These cards claim to enhance “brain power” (腦力; naoli) and “five senses” (五感; wugan). Although these claims are vague, they are indeed enticing ideas that echo the folk belief of the human mind and the neuroscientific notion of plasticity. Moreover, they resonate the ever-increasing anxiety among Taiwanese parents about competition and excellence in the globalising world (Lan 2018). Thus, neuroscience and parenting are combined and reflected through the use of heibaika, among many other similar gadgets and interventions that aim to improve children’s brain, the biological seat that shapes and potentiates a person. As human potential can be cultivated given adequate stimulation, then who should be most responsible for providing such stimulation? Certainly, parents.

Heibaika and PCCs

Another venue of promoting heibaika is PCCs, which signify a fascinating combination of tradition and modernity and where these cards become a symbol of quality and science of baby care. A tradition specific to postpartum women in Chinese culture has been well practiced: zuoyuezi (做月子, literally “doing the month”). A woman who just delivered is widely believed to need to recuperate for a period of time, usually a month, during which she is required to follow a certain regime of eating and living so as to resume her health. Many taboos are also recognised during this period, otherwise the woman’s health will be impaired by the event of childbirth (Pillsbury 1978; Holroyd et al. 1997; Steinberg 1996). Given that zuoyuezi is considered crucial, it was usually done at home where the postpartum woman was taken care of by her own mother or mother-in-law. However, the tradition of zuoyuezi has slowly but steadily transformed into a modernised version and contributed to the rise of PCCs (or in Chinese, 月子中心 yuezi zhongxin). These centres offer quiet and comfortable rooms, nursing services, nutritious diet and professional baby care at the price of 150 to 300 USD a day, similar to that of a leading hotel. These centres have become a favourite for postpartum women, particularly in urban areas over the past two decades (Huang 2006).

The burgeoning of PCCs is beyond the scope of this article, but the fact that their increasing number in Taiwan (Fig. 2) appears to go in tandem with the prevalence of heibaika is noteworthy. Chu-hong, a senior staff member, said that when she helped establish the PCC in 2009, she noticed that “wherever you go, everyone is attaching heibaika on the baby cart, just beside babies’ little faces” (see Fig. 1). She reasoned that heibaika became a must-have because preparing one for each baby costs little and it implied the quality of care. For her, “It is simply a commercial tactic. We just tell parents that we are helping infants develop their potentiality”. However, when I further inquired into her opinion of infants who really stared at heibaika, she gave an ambiguous answer: “Usually, such babies [who responded better to black-and-white stimuli] are more attentive and highly interested in anything”.

In a burgeoning and competitive market of postpartum care, heibaika symbolise the intention of PCCs to satisfy parents, their target customers. In addition to common postpartum care for mothers, such as nutritious diet and quiet rest, the things that can be offered to the newborn life become a niche for business. Consequently, classical music (although not necessarily Mozart) is constantly played in the baby room and heibaika are always present in each and every baby’s cart. PCCs have become a showroom of neuroparenting, where these cards and music are standard equipment.

To understand the prevalence of heibaika among PCCs, a phone survey to all registered PCCs in Taipei City and New Taipei City was conducted in April 2016. The results are shown in Table 1.

Despite the moderate response rate (45/100), over 90% of the PCCs that responded (41/45) revealed that they provided heibaika. If we extrapolate this finding to all PCCs, then the use of heibaika is present in over 90% of PCCs throughout the country.

In 2016, 208,440 births were recorded, corresponding to approximately 200,000 women who gave birth, supposing that some of them have twins or triplets (Ministry of the Interior 2018a). The total number of admissions (including mothers and babies) to PCCs in the same year was 89,515 (Ministry of Health and Welfare 2018). Therefore, an estimated 44,000 women stayed in PCCs. That is, approximately 22% of the women who gave birth in the same year stayed in a PCC.

The combination of the survey findings and government statistics shows a reasonable estimate that one-fifth Taiwanese women who gave birth in 2016 would know of heibaika in the PCCs where they stayed in. In short, PCCs as a modernised, commercialised, and organised provider of the zuoyuezi tradition have greatly contributed to the promulgation of heibaika.

Translating neuroscience, transforming parenting

Although heibaika represent a phenomenon of local neuroculture in Taiwan where lay neuroscience interweaves with parenting culture, its emergence and expansion are not ungrounded. In fact, these cards arose in conjunction with a great trend of introducing and translating neuroscience-informed parenting books in Taiwan since the late 1990s, i.e. ‘the Era of the Brain’ (Rose and Abi-Rachad 2013; Lowe et al. 2015; Racine et al. 2010).

Here, we discuss local manifestations of the convergence of the two trends of globalisation, namely neuroscience and parenting. Although Faircloth et al. (2013) argue for a global perspective on parenting, studies focused on the ways of globalising parenting have been few. One approach to this issue, I suggest, is through studying translation, and I contend that this approach also applies to the study on globalisation of neuroscientific knowledge. Globalisation cannot take effect without local translation.

The institutionalisation of neuroscience in Taiwan is relatively late compared with that of other bio-scientific departments. However, many scholars have promoted the importance of neuroscience within and without academia since the 1990s. Translating foreign works on cognitive psychology and neuroscience is one of their endeavours, e.g. the translation of Jacques Mehler and Emmanuel Dupoux’s What Infants Know by Professor Daisy L. Hung in 1996. The book was published originally in French in 1990 (Naître Humain) and translated into English in 1994. It is a scientific introduction to the cognition of infants that draws on experimental evidence, which was written by two leading psychologists. Although it is not about parenting, Hung contended that the book invalidates such commercial advertisements as “making the baby beautiful by looking at the posters of movie stars” or “teaching languages to unborn foetuses” (Hung 1996). Moreover, Hung drew a sharp line between authentic science and folk belief. For the past two decades, she has been a prominent figure in translating psychological and neuroscientific works into Chinese, including Thinking, Fast and Slow of Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman. Although her translation is sometimes criticised for questionable quality, the act of translation itself signifies a noteworthy step of globalising neuro-knowledge.

Meanwhile, translated books that help globalise parenting skills on the basis of clinical science (medicine or nursing) are also available, which have an even longer history. A pertinent example that specifically addresses the developmental benefits of sensory stimulation for babies is Susan Ludington and Susan Golant’s How to Have a Smarter Baby: The Infant Stimulation Program for Enhancing Your Baby’s Natural Development (1987; Chinese translation in 1999). The book was co-authored by a nursing professor (Luddington) and a professional writer (Golant). Further, it recommends adequate sensory stimulation (e.g. visual, auditory, and tactile) because they facilitate the development of babies, including the use of black-and-white pictures as a manner of stimulating the vision of babies. The method was originally used in the neonatal intensive care unit based on Ludington’s own study on premature infants (Chaze and Ludington-Hoe 1984). Although the authors have affirmed that showing the black-and-white cards may be a good method of making the infant brain active even for healthy babies, whether their affirmation is true given available evidence is unclear. In addition, it is disputable whether physical stimulation per se, rather than the accompanying emotional attachment when giving the stimulation, is the defining factor for positive outcomes.

The translated knowledge is apparently at best piecemeal, i.e. it is never systemic and integrated. Consequently, the partitioned viewpoints of parenting are the rule. For instance, a frequent topic in online discussion groups is the contrast between Dr. William Sears’ attachment parenting and Dr. Leila Denmark’s disciplinary parenting. Sporadically, Taiwanese parents quarrel with each other over issues such as holding the baby too much (or too little), sleeping together with the baby (or separately), and holding on (or giving in) when the baby cries incessantly. Both are professional perspectives, but their authority does not eliminate controversy.

Recent bestsellers have further conjoined neuroscience and parenting and represented neuroparenting better, e.g. John Medina’s Brain Rules for Baby: How to Raise a Smart and Happy Child from Zero to Five (2010; Chinese Translation in 2012) and Sandra Aamodt and Sam Wang’s Welcome to Your Child’s Brain: How the Mind Grows from Conception to College (2011; Chinese translation in 2012). The stronger linkage of such books between lab-based neuroscience and real-life parenting advice distinguishes them from earlier translated works. Therefore, they translate lab science into parenting advice, just as translational medicine that aims to apply lab findings to clinical practices (or from the bench to the bed). In a Deleuzean sense (Deleuze and Guattari 1998), the molar and the molecular aspects of parenting are integrated and illustrated in such popular science books.

Translation represents more than a textual remaking, faithful or not. It implies a globalisation of knowledge, attitude, and practice, along with the local transformations that ensue. Notably, the purchase of neuroparenting depends equally on the supple side and the demand side. While translated books signify the import of knowledge supplied from other countries, it takes receptive parents who demand and absorb such information. In the case of Taiwan, parents are all the more stressed out about cultivating their offspring in the era of globalisation. A recent book by Doepke and Zilibotti (2019) contended that parenting is a function of economy. As economic inequalities deepen and aggravate, parents tend to be more authoritative and authoritarian to ensure that their offspring will have a better chance of upward social mobility. Furthermore, Lan’s (2018) recent book perfectly addressed the anticipation and anxiety of contemporary Taiwanese parents, who grew up in a time of neoliberalism and struggled with the two opposing parenting ideals. On the one hand, they consider adopting a harsh ‘Tiger Mother’ image (Chua 2011) and the ‘win at the starting line’ mindset (Wong and Rao 2015) necessary. On the other hand, they are attracted by the egalitarian and occasionally ‘laissez-faire’ method of raising kids the natural way. Prominent mostly among mothers, the anxiety of raising kids in a time of compressed modernity (Lan 2014) is reflected by their choice of education (schools, curricula, and extracurricular activities), life environment, and even the places of birth of their children for the sake of double or flexible citizenship (Ong 1999). Similarly, Kuan (2015)’s description of parenting practices in China is no less easy and peaceful. Class, gender, and regions of residence matter to a large extent in their cases. However, Lan’s and Kuan’s works focus on the relationship of parents with their school-age children (or even older ones). By contrast, my case addresses parenting for newborn infants when school education appears remote and irrelevant. However, these educational issues, along with the sense of ambivalence in the aforementioned case studies, are already and actively present in the minds of parents when they use heibaika upon their babies. Heibaika thus become a biopsy of parental anxiety in a time of globalisation.

How parents view heibaika: believers, sceptics, and cautious experimenters

The 22 parents that I interviewed throughout the research period (2015–2017) are by no means representative of the entire population in Taiwan. As mentioned, one night in a PCC costs as much as one night in a top-notch hotel, and most postpartum women spend at least two weeks there. Those with fewer resources may not afford such service. Therefore, recruiting a better-off class of parents is likely when sampling them from a PCC, which is reflected by their social characteristics: all the respondents are well educated (college level or above), all except one have a regular, full-time job, and the majority are in their 30s. All but two were having their first baby, which corresponds to the lowering fertility rate that is troubling Taiwan (1.170 per woman 15 to 49 years old in 2016, according to the Ministry of the Interior 2018b). As interviews were conducted during daytime, when the fathers were out for work, only one of the respondents is male. He was interviewed along with his postpartum wife. Therefore, the analysis of interview contents is inevitably leaning towards the perspective of mothers, which is also the case for parenting in Taiwan (Lan 2018), where mothers take care of the majority of work with kids.

Most parents reported having no knowledge of heibaika prior to pregnancy, and PCC is the first place for them to learn about these cards. This finding echoes my aforementioned survey of PCC and heibaika. According to their attitudes towards heibaika, these parents can be tentatively classified into three types: believers, sceptics, and cautious experimenters. However, the classification is not fixed. Parents may easily shift from one class to another.

A ‘believer’ parent Jia-yen describes her use of heibaika with her baby:

When she stays awake more often, you can really see her staring at such things [heibaika]……and [she stares] differently to pictures on her left and right sides. The left side is a black-and-white checkerboard, and the right side is a house-shaped picture with less contrast. Obviously, she likes the black-and-white checkerboard. Yeah, when I let her sit on the bed and play with her, or when she starts to throw tantrum, I show her the card and she would really react to it…. (Author: She would then calm down?) She would simply focus on the card, yes.

Calming and concentration appear to be the most cherished effects of heibaika for these parents as far as they are concerned. Although believer parents interpret the response of their babies as positive, they value the observable behavioural manifestations rather than the hope for unintelligible ‘brain effects’. However, even for those who thought that these cards are good for intelligence, they could not explain why and how they are beneficial to the young brain when the baby is attentive to the cards, nor would they care. More likely, parents are simply trying to find a way of getting along with these new little creatures. These parents believe because their experimentation with the cards tells them this way. Another mother Ya-chin explained how she applied these cards to adjust the sleep–wake cycle of her baby.

When I finish feeding her in the daytime, I play with her for 30 min up to an hour. I play with her using these cards consecutively for 10 to 20 min. I also play music for her or anything to keep her awake. Tease her and play with her and she would get tired in an hour. Actually, I am quite curious how her brain is stimulated this way.

For now, her attitude stands on the border between believers and cautious experimenters, and whether she will count herself a sceptic once her heibaika experiment with her baby fails is uncertain.

In addition to the everyday experiments, heibaika occasionally becomes a projection that mixes up parents’ past experiences of growing up and their anticipations for the children’s future. These cards are invested with the desires, wishes, and imaginations of parents. A respondent, Yi-wen, reflected over her life, which is impressively illustrative of the ingrained tension felt by these parents. Born in the 1980s, when the economy of Taiwan was rising quickly, she was raised by her grandparents most of the time because her parents were both occupied by work. She was disappointed by the lack of parental company, which she felt was the cause for her sporadic feelings of insecurity. “My parents wanted me to be smart, to achieve something in my field, which I think I do. Maybe they are not so satisfied with me, but it’s okay”, she shrugged. She recalled her decision to finally have a baby after 5 years of marriage and the unexpected symptoms (severe nausea and vomiting into the third trimester) and complications (thyroid enlargement and hyper-function) during pregnancy. All these factors came down to her feelings towards the newcomer of her family. She reasoned that her purchase of various toys, including heibaika, was a way of building security for her baby. She explained:

I want to somehow provide my baby with the sense of security as a way of compensation [for myself]. Certainly, my intelligence may not be so good [as my parents], and I hope my baby’s will be. It’s just that IQ may not be the most important aspect that I value.

Yi-wen could neither clarify nor elaborate what she valued and how these cards could provide the ‘sense of security’, but how she used heibaika as a way to deal with her own sense of inferiority and insecurity is amazing. Heibaika are not just an instrument of intelligence and attachment; they are also embodiment of parental anticipation. Adams et al. (2009) elucidated that anticipation is not simply a forward-looking attitude, but more likely a back-and-forth (or in their words, abductive) state that mingles prospection and retrospection. Heibaika represent this anticipation of parents and articulate their emotions now and then, and here and there.

Furthermore, sceptic parents are not disbelievers from the start. Instead, they become sceptic after the claimed effects of heibaika (i.e. babies staring at cards and showing attention and reactivity) did not take place as expected. Yen-jong told me, “My baby is sleeping all the time. She seldom opened her eyes, so I think heibaika have no appeal to her”. She admitted having heard people talk about these cards since her pregnancy, but from her own observation, she was uncertain how these “simple shapes” could possibly act on the brain of the infant.

The only interview that involved both parents is illuminating because it compares Taiwan and China and confirms the uniqueness of the heibaika phenomenon in Taiwan. The father, Ren-chin, is a Taiwanese and the mother, Jia-lun, is a Chinese. They originally lived in Shanghai but decided to move to Taipei for their baby when Jia-lun was 7 months pregnant. They never heard about heibaika in Shanghai. When they first saw these cards in this PCC, they thought that they were meant to prevent the baby from looking outside, just like the fly mask for the horse. I asked them to compare parenting in Taiwan versus that in China.

Jia-lun said, “Most people [in China] seldom talk about parenting in the newborn stage. They generally talk about experiences of feeding the baby or what product is good …”. Ren-chin added, “Usually the peak of discussion [on parenting] is when the baby is reaching one year of age”.

Thereafter, Jia-lun continued to address the difference between Taiwan and China,

They particularly emphasize early education in China, much more than Taiwanese people do. For instance, they offer educational courses for babies as young as 8 or 9 months old, the courses on dancing, body movement, or simply showing them music and pictures. We have quite a few friends who are actively preparing their one-year-old or two-year-old kids for the kindergarten, well, entrance exams for the kindergarten.

Ren-chin later commented during the interview, “The emphasis on early education reflects people’s concern about unequal educational resources”. His remark somehow resonates with the point of Doepke and Zilibotti (2019).

Shan-yi is another mother from China who also notices the difference across the Taiwan Strait. She heard about heibaika only after getting pregnant. “My friends [in China] told me they know these cards, but they are not as enthusiastic as Taiwanese people are”, and she added, “None of my Chinese friends who are pregnant tell me to buy these cards, but those Taiwanese friends will”.

The comparison of parenting styles in China and Taiwan is a fascinating topic, but it is beyond the scope of this paper. Nonetheless, this paragraph perfectly illustrates the local variation of global parenting or ‘glocal entanglement’ of parenting (Lan 2014), which weaves the overarching socio-economic-educational environment into the most intimate and individualised practices.

Discussion: contributing factors in the popularisation of heibaika

In sum, the popularisation of heibaika is made possible by the combination of many social, economic, and cultural factors. Science is never the defining one. The scientific robustness of heibaika does not bother these parents, because using heibaika is harmless anyway. Moreover, these parents are neither ignorant nor indifferent to scientific evidence; they simply look for something else. First, in real life, heibaika are used more as an interactive tool than an enlightening instrument, and these parents value emotional maturity more than intellectual performance. That is, they hope for a cheerful, independent, and resilient child more than a smart one. The charm of heibaika does not reside in the potential benefit to intelligence or vision but in the effects on emotion and personality that can be noted through parent–child interactions. Second, parents use heibaika on their infants, try several different manoeuvres and conclude from observed effects, just as scientists manipulate variables and record findings to reach a robust fact. The baby may be a ‘scientist in the crib’ (Gopnik et al. 2000), whereas the parents are ‘scientists by the crib’, who eventually become believers, sceptics, or cautious (and perhaps undecided) experimenters.

The lay neuroscience that these parents are practicing treats the infant brain not only as a physical presence and a scientific object but also as a blank screen to project the desires and anticipations of parents, thereby drawing from their own past experiences of growing up as a child. Notably, their imagination of the infant brain is imbricated by their own class and gender as well as the social conditions in Taiwan, thereby contributing to each and every different form of anticipation for the baby. Therefore, lay neuroscience merges with parenting culture to the extent of indistinction and reflects a larger context where parenting is taking place among myriad considerations of class, migration and personal achievement (see also Lan 2018). Although marginal most of the time, these cards are silently integrated into everyday parent–child activities as a tool for neuroparenting and thus attest to the presence of lay neuroscience.

Conclusion: what heibaika tell us about neuroparenting and lay neuroscience

To my knowledge, the present study is the first attempt to explore black-and-white cards and neurocultural phenomena in settings outside Europe and North America. It has contributed to science and technology studies (STS) in at least three aspects.

First, the study directs current emphasis on lab neuroscience to lay neuroscience and compels readers to rethink and problematise the boundary of science and culture. Boundary work is a frequent theme in STS (Gieryn 1993). This article is not intended to address how the boundary work is done, but how the boundary can be reconceptualised and reworked by studying lay neuroscience. It is another way of rearticulating the fact that boundary is not given but something that must be made. The presence of lay neuroscience attests to the murky zone between science and non-science (ergo, culture) where these two are commonly indistinguishable. Unlike lab neuroscience, lay neuroscience is usually inescapable from multiple readings and interpretations. While heibaika may not be practically effective in improving infantile vision or ‘intelligence’ (if those can be measured), these cards are not entirely useless because parents are indeed able to build an attachment relationship with the baby and thus observe desired behavioural effects, e.g. calming, concentrating, and better sleeping.

Second, the study enriches the concept of neuroparenting. Macvarish’s original idea of neuroparenting (2016) referred to the infiltration of modern neuroscience into parenting culture that used to rely on traditional wisdom, personal experience, and social convention. Neuroparenting can be considered a new form of life that aggravates and intensifies scientific motherhood. However, the idea of neuroparenting still sits within a conceptual dichotomy of science and culture, where a certain manner of parenting is endorsed by formal science and enforced by the therapeutic state. In this paper, the examples of heibaika or Mozart music for the baby are not validated by neither formal science nor the state, but they still prevail in common life. Rigorously speaking, the topic of this study is not about public understanding of science (Wynne 1991, Ziman 1991); it is about the understanding of public (or lay) science. I contend that the study on such forms of neuroparenting as heibaika may cast our attention to the equally popular domains of parenting which may not be supported by science and institutionalised by the state but represent the rationality and imagination of the public.

Third, this study offers an invaluable case study on the phenomenal complexity between local variation and globalising tendency of neuroculture. Neuroculture depends on neuro-knowledge, which travels across continents and countries. However, their spread apparently takes root because parents in Taiwan are receptive. They are receptive because they are anxious in a time of globalisation when their past and the future of their children are amalgamated in the anticipation that crystalises in everyday choices such as heibaika. Heibaika thus stand as the empirical hinge of macroscopic conditions and microscopic interactions. Moreover, they help researchers examine how structure and agency are entangled in everyday parenting through promulgating neuro-knowledge, modernised zuoyuezi traditions, and online communication.

This paper does not address parents who are rural, uneducated, or unable to afford the luxury of staying in a PCC. Whether they feel the same about heibaika as the better-off respondents in this study is never known. In addition, further research is urgently needed to investigate whether the transnational spread of neuroculture follows the same route in other countries and how neuroculture translates into other domains of life, such as commerce and policy.

In sum, this paper is intended to alert concerned readers to appreciate a wider realm of everyday life and the science, recognised or not, within it. This case study of heibaika opens up a knowledge space that is empirically novel, theoretically challenging and practically beyond black and white.

References

Adams, V., M. Murphy, and A.E. Clarke. 2009. Anticipation: Technoscience, Life, Affect, Temporality. Subjectivity 28 (1): 246–265.

Apple, R. 1995. Constructing Mothers: Scientific Motherhood in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Social History of Medicine 8 (2): 161–178.

Bangerter, A., and C. Heath. 2004. The Mozart Effect: Tracking the Evolution of a Scientific Legend. British Journal of Social Psychology 43: 605–623.

Beauvais, C. 2015. The ‘Mozart Effect’: A Sociological Reappraisal. Cultural Sociology 9: 185–202.

Chabris, C.F. 1999. Prelude or Requiem for the ‘Mozart Effect’? Nature 400: 826–827.

Chaze, B.A., and S.M. Ludington-Hoe. 1984. Sensory Stimulation in the NICU. The American Journal of Nursing 84: 68–71.

Chua, A. 2011. Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. New York: Penguin Books.

Clarke, A.E. 2005. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1998. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Doepke, M., and F. Zilibotti. 2019. Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Doyle, E. 2013. Seeking Advice about Children’s Health in an Online Parenting Forum. Medical Sociology Online 7: 17–28.

Dumit, J. 2004. Picturing Personhood: Brain Scans and Biomedical Identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dundon, N.M., C. Bertini, E. Ladavas, B.A. Sabel, and C. Gall. 2015. Visual Rehabilitation: Visual Scanning, Multisensory Stimulation and Vision Restoration Trainings. Frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience 9: 192.

Faircloth, C., D.M. Hoffman, and L.L. Layne. 2013. Parenting in Global Perspective: Negotiating Ideologies of Kinship, Self and Politics. London: Routledge.

Fantz, R.L. 1963. Pattern Vision in Newborn Infants. Science 140: 296–297.

Franks, D.D. 2010. Neurosociology: The Nexus between Neuroscience and Social Psychology. New York: Springer.

Frazzetto, G., and S. Anker. 2009. Neuroculture. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10: 815–821.

Gieryn, T. 1993. Boundary Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists. American Sociological Review 48 (6): 781–795.

Gopnik, A., A.N. Meltzoff, and P.K. Kuhl. 2000. The Scientist in the Crib: What Early Learning Tells Us about the Mind. New York: William Morrow.

Hammond, C. 2013. Does Listening to Mozart Really Boost Your Brain Power? http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20130107-can-mozart-boost-brainpower?ocid=global_future_rss. Accessed 14 Aug 2018.

Hays, S. 1998. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Holroyd, E., F.K.L. Katie, L.S. Chun, and S.W. Ha. 1997. “Doing the Month”: An Exploration of Postpartum Practices in Chinese Women. Health Care for Women International 18: 301–313.

Huang, C. 2006. Postpartum Rest and Postpartum Rest Centre: A New Industry from Old Custom [Chinese]. The Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theater, and Folklore 152: 139–174.

Hubel, D.H., and T.N. Wiesel. 1962. Receptive Fields, Binocular Interaction and Functional Architecture in the Cat’s Visual Cortex. Journal of Physiology 160: 106–154.

Hung, D.L. 1996. Translator’s Preface: Knowing Naturally or Knowing through Learning? In Naître Humain. [Chinese translation version], ed. J. Mehler and E. Dupoux. Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing Co. Not paginated.

Jenkins, J.S. 2001. The Mozart Effect. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 94: 170–172.

Johnson, S. 2004. Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life. New York: Scribner.

Kuan, T. 2015. Love’s Uncertainty: The Politics and Ethics of Child Rearing in Contemporary China. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lan, P.-C. 2014. Compressed Modernity and Glocal Entanglement: The Contested Transformation of Parenting Discourses in Postwar Taiwan. Current Sociology 62: 531–549.

Lan, P.-C. 2018. Raising Global Families: Parenting, Immigration, and Class in Taiwan and the US. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lebowitz, S. 2017. Millennial parents are doing things differently than any other generation before them. https://www.businessinsider.com/millennials-turn-to-the-internet-for-parenting-advice-2017-11. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Levy, N. 2011. Autonomy, Responsibility and the Oscillation of Preference. In Addiction Neuroethics: The Ethics of Addiction Neuroscience Research and Treatment, ed. A. Carter, W.D. Hall, and J. Illes, 139–151. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: University of British Columbia.

Lin, X. 2014. Can Heibaika Promote Infant Visual Development? [Chinese]. https://pansci.asia/archives/69528. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Lowe, P., E. Lee, and J. Macvarish. 2015. Biologising Parenting: Neuroscience Discourse, English Social and Public Health Policy and Understandings of the Child. Sociology of Health & Illness 37: 198–211.

Macvarish, J. 2016. Neuroparenting: The Expert Invasion of Family Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2018. Statistics of the Current Status of Health Care Institutions and Services. https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/np-1864-113.html. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

Ministry of the Interior. 2018a. Department of Statistics. https://www.moi.gov.tw/stat. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

Ministry of the Interior. 2018b. Department of Household Registration. https://www.ris.gov.tw/346. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

O’Connor, C., G. Rees, and H. Joffe. 2012. Neuroscience in the Public Sphere. Neuron 74: 220–226.

Ong, A. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Oprescu, F., S. Cambo, J. Lowe, J. Andsager, and J.A. Morcuende. 2013. Online Information Exchanges for Parents of Children with a Rare Health Condition: Key Findings from an Online Support Community. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15: e16.

Ortega, F., and F. Vidal (eds.). 2011. Neurocultures: Glimpses into an Expanding Universe. Frankfurt am Maine: Peter Lang.

Pietschnig, J., M. Voracek, and A.K. Formann. 2010. Mozart effect–Shmozart Effect: A Meta-analysis. Intelligence 38: 314–323.

Pillsbury, B.L.K. 1978. “Doing the Month”: Confinement and Convalescence of Chinese Women after Childbirth. Social Science and Medicine 12: 11–22.

Plantin, L., and K. Daneback. 2009. Parenthood, Information and Support on the Internet. A Literature Review of Research on Parents and Professionals Online. BMC Family Practice 10: 34.

Racine, E., O. Bar-Ilan, and J. Illes. 2005. fMRI in the Public Eye. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6: 159–164.

Racine, E., O. Bar-Ilan, and J. Illes. 2006. Brain Imaging: A Decade of Coverage in the Print Media. Science Communication 28: 122–142.

Racine, E., S. Waldman, J. Rosenberg, and J. Illes. 2010. Contemporary Neuroscience in the Media. Social Science and Medicine 71: 725–733.

Rauscher, F.H. 1999. Prelude or Requiem for the ‘Mozart Effect’? Nature 400: 828.

Rauscher, F.H., G.L. Shaw, and K.N. Ky. 1993. Music and Spatial Task Performance. Nature 365: 611.

Rolls, E.T. 2012. Neuroculture: On the Implications of Brain Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rose, N., and J.M. Abi-Rachad. 2013. Neuro: The New Brain Sciences and the Management of the Mind. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Santer, M., I. Muller, L. Yardley, H. Burgess, S.J. Ersser, S. Lewis-Jones, and P. Little. 2015. ‘You Don’t Know Which Bits to Believe’: Qualitative Study Exploring Carers’ Experience of Seeking Information on the Internet About Childhood Eczema. British Medical Journal Open 5: e006339.

Schickedanz, J.A., D.I. Schickedanz, P.D. Forsyth, and G.A. Forsyth. 1998. Understanding Children and Adolescents. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Shaw, G. 2005. Mozart Effect. Encyclopaedia of Human Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Steele, K.M., S.D. Bella, I. Peretz, T. Dunlop, L.A. Dawe, G.K. Humphery, R.A. Shannon, J.L. Kirby Jr., and C.G. Olmstead. 1999. Preclude or Requiem for the ‘Mozart Effect’? Nature 400: 827.

Steinberg, S. 1996. Childbearing Research: A Transcultural Review. Social Science and Medicine 43: 1765–1784.

Wiesel, T.N., and D.H. Hubel. 1965. Extent of Recovery from the Effects of Visual Deprivation in Kittens. Journal of Neurophysiology 28: 1060–1072.

Wong, J.M.S., and N. Rao. 2015. The Evolution of Early Childhood Education Policy in Hong Kong. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy 9: 3.

Wynne, B. 1991. Knowledges in Context. Science, Technology and Human Values 16: 111–121.

Ziman, J. 1991. Public Understanding of Science. Science, Technology and Human Values 16: 99–105.

Acknowledgements

This research is sponsored by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104-2410-H-010-007-MY2). I would like to thank Yu-Ping Chen, Yu-Fang Shen and Zsofia Samodai for assisting me in this study. The various versions of this study were reported in the 2016 and the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Taiwanese Sociological Association and the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Society for Social Studies of Science (4S), where I gratefully received many precious suggestions. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this paper, whose comments have greatly improved it.

Funding

This research is sponsored by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104-2410-H-010-007-MY2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests—intellectual or financial—in the research detailed in the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The author confirms that the manuscript is comprised of original material that is not under review elsewhere, and that the study on which the research is based has been subject to appropriate ethical review (Institutional Review Board of National Yang-Ming University, No. YM103110E).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Js. Beyond black and white: heibaika, neuroparenting, and lay neuroscience. BioSocieties 16, 70–87 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-019-00180-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-019-00180-6