Abstract

In this article on innovative medical treatment for serious conditions in Japan, we aim to revise two widespread notions: first, that people living with severe conditions are all waiting for a cure or are impatient to try out experimental treatment, in particular regenerative medicine. Showing that motivations for cure seeking are complex and linked to somatic identity, we argue that gaining a cure also means a new social normality, which for some people narrows the only normality that is meaningful to them; and, second, that people living with a serious (latent) condition necessarily define their lives as not normal in the light of normalisation. People with a condition conceptualise normal life variously and multiply in the light of both individual and collective experiences. The two revisions are crucial to attempts at understanding what makes people seek experimental medicine. Comparing the narratives of people with four different conditions – spinal cord injury, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Diabetes Mellitus type 1 and cardiovascular disease – it becomes clear that the difference between seeking treatment or not largely depends on somatic identities; rather than through notions of (ab)normality, it is more adequately understood in terms of the experience of somatic lacking and wholeness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Regenerative medicine – among which various stem cell therapies – can be broadly defined as a branch of translational research in tissue engineering and molecular biology. It deals with the process of “replacing, engineering or regenerating human cells, tissues or organs to restore or establish what is regarded as ‘normal function’” (Mason and Dunnill, 2008, p. 4). According to Foucauldian theory the value of ‘health’ in modern, technologically advanced societies is normalising, as it interconnects the qualification of individuals as ‘normal’ human beings with the imperative of correction (Foucault, 2003) as well as with the principles of discipline and biopower (Foucault, 1994, 2003). Our research nuances this stance by exploring why some people with a serious condition seek experimental stem cell and other biomedical interventions, while others do not. Our findings indicate that the will to adjust the self as part of the processes of normalisation and responsibilisation (Rose, 2007), though important, is too easily presumed in the light of what we refer to as the ‘dominant normal’.

Debates on ‘normality’ among scholars of disability studies criticise the dominant views of disability as ‘provisional’ and ‘problematic’ (Campbell, 2012). For, in a world that ‘normalises’ disability, a ‘cure’ is seen as the quintessential solution and rehabilitation and education second best (Tichkasky and Michalko, 2012; Tremain, 2005). Some authors speak of the ‘biotechnological illusion’, questioning the idea that biotech enhancement or ‘normalisation’ can take place without considerable efforts and sacrifice, and that normalisation can fix ‘the problem’ (Winance et al, 2015). Others have criticised forms of health governance that define individuals as autonomous subjects expected to make ‘responsible’ choices among a narrowed down range of options (Callon and Rabeharisao, 2004; Davis, 2002, p. 30; Ho, 2008). On the other hand, there are also patient and health organisations that zealously engage in activities aimed at finding stem cell ‘cures’ and ‘treatment’ (Sleeboom-Faulkner et al, 2016) and many patients participate in website forums on the internet (Song, 2017; Kim, 2012) in the hope to find innovative biomedical cures or means to raise their quality of life.

Experimental intervention in the field of regenerative medicine is an interesting case, as overall uncertainty exists about whether their application is safe and can lead, to ‘correction’ or ‘return to normal’. These issues prompt us, not just to consider a variety of conditions that define the relation between disability and normalisation, but also to probe further into the subjectivities of people who question dominant notions of ‘the normal’. The uncertainty around experimental biomedical technologies has led to various debates, whereby some encourage the swift development of the field of regenerative medicine and urge their accelerated application to cure patients; others, however, have described this haste as ‘hyping’ in terms of the ‘politics of hope’ (Brown and Michael, 2004; Novas, 2006; Hyun, 2013; Petersen et al, 2017), arguing instead for a ‘responsible’ and ‘ethical’ approach based on scientific evidence (Bianco and Sipp, 2014; McMahon and Thorsteinsdóttir, 2010; Ogbogu et al, 2013). Although interviews have been held with patients seeking stem cell treatment (Song, 2017; Patra and Sleeboom-Faulkner 2011; Sui and Sleeboom-Faulkner, 2015; Bharadwaj; Chen and Gottweis, 2013; Salter et al, 2015), the debates, however, have not been based on the diversity of views among people with various diseases and disabilities.

In this study it will become clear that, rather than just one hegemonic view, various discourses of normality reign and a wide spectrum of factors, conditions and motivations are involved in the decision-making around experimental treatment. Patients express a great diversity of reasons for undergoing regenerative medical interventions, varying from ‘last resort’ and ‘improving the quality of life’ to following examples (‘others have done it’) and calculation (‘I can afford it’; ‘I stand a good chance’), while motivations varied from spiritual (hope, prayer, pilgrimage) and altruistic (I do it for my family; perhaps other patients can benefit) (cf Song, 2010; Patra and Sleeboom-Faulkner 2011; Sui and Sleeboom-Faulkner, 2015; Bharadwaj, 2013; Sakai, 2014). Here, we try to deepen our understanding of decision-making on seeking treatment by examining how aims are set and motivations are forged in relation to people’s particular condition.

Seeking innovative/experimental treatment

A variety of biomedical stem cell interventions have attracted the attention of patients. A well-known type of stem cell is the embryonic stem cell, a so-called pluripotent stem cell, which has the ability to develop into all cells of the body. However, as it involves the destruction (or at least manipulation) of the embryo, it is controversial, and the use of the embryo or foetus for the purpose of stem cell therapy is not allowed in Japan (Mikami and Stephens, 2016; Sleeboom-Faulkner, 2008; Sleeboom-Faulkner et al, 2016). Currently, another kind of pluripotent stem cell called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) is providing hope to many patients in Japan. Human iPS cells were pioneered in 2007 by 2012 Nobel laureate Shinya Yamanaka. In Japan iPS has raised many expectations both for its extraordinary ability to generate embryo-like cells from adult tissues and for its indigenous origin (CiRA, 2015). Government support and deregulation have accelerated the clinical application of cell therapy, and in autumn 2014, a human clinical study using iPS was initiated with patients suffering from age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Kyoto University News, 2016), followed by the announcement of an official list of other candidate diseases to be treated using iPS (CiRA, 2015).

There are many other advanced biotech treatments under development, which are thought to raise the hopes of patients and people with disabilities on a return to ‘normal’ life. For instance, cell sheet engineering, which is currently under clinical experiment in Japan, has raised the expectations of people with cardiovascular disease (Okano, 2012). But although regenerative medicine is providing hope to patients, at the time of field research these treatments were not yet firmly established or recognised internationally. Nevertheless, some patients are longing for opportunities for clinical experiments at home even when risk is involved. Others, however, prioritise safety and wait until treatment is established. Some patients might travel abroad for controversial cell treatment, including embryonic stem cells, while others do not. The question we explore in this article concerns the differences in this decision-making. It is often presumed that whether persons with a disability try out unrecognised stem cell interventions and travel abroad for controversial treatments depends on the urgency of the diseases and the financial situation of patients (interview, journalists, 13 May 2014; Tamai and Kasuga, 2009, p. 16). However, our research indicates that persons with seemingly urgent conditions are not necessarily more desperate for regenerative medicine than those with less urgent conditions; and, the financially well-off are not necessarily more enthusiastic about travelling abroad for new medicine than those who are less well-off, even when formally recommended treatment is available.

The expectations individuals with disabilities have of regenerative medicine and their desire to be cured are intimately related to their ‘knowledge’, perceptions and experiences of their condition. Such perceptions and experiences are formed through both their somatic experiences and the socio-cultural conditions of their history, and their institutional and socio-cultural environment. We refer to this as their somatic identities, a notion related to that of ‘somatic individuals’ (Novas and Rose, 2000) and ‘biological citizenship’ (Petryna, 2002; Rose, 2007). Whereas the concept of somatic individual refers to the new relations between body and self, which have become possible through genomics and other biotechnology, we place the concept of somatic identity in the context of somatic experience and group identity. Here, we do not so much refer to the socio-political organisation of individuals that share a somatic identity, as is the case with the notion of ‘biological citizenship’, but we use it as an analytical concept to understand the formal/informal decision-making of individuals on the basis of their disease/disability experience. For example, a person’s struggles with certain disease symptoms could differ depending on the effects of pre-existing treatment. The availability of wheelchairs and other medical devices and medical insurance influences the experience of disease. The life satisfaction of individuals with a disability may also depend on employment opportunities and infrastructures for sports activities and relaxation. The history of the social perception of a disease matters, too, for instance, when a disease has been intensely disliked in society and has been a target of eugenics. The activities of health movements, such as campaigns against stigmatisation, too, can influence the self-image of individuals with particular conditions.

Normality and the importance of somatic identity

In this article, we analyse narratives of persons with four different diseases regarding their decision to seek innovative medical interventions. We have focused in particular on the notions of ‘being cured’, ‘expectations of regenerative medicine’ and the actions undertaken by them to ‘find a cure’, while taking into account the various socio-cultural meanings of their diseases in the context of Japan. The four diseases in question include spinal cord injury (SCI), diabetes mellitus type 1 (DM1), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and cardio vascular disease (CVD). From the outset, we expect that the different characters of these diseases would shed light on factors important in seeking medical intervention. The conditions differ in various respects: they can be genetically inherited (DMD, sometimes DM1 and CVD) or acquired suddenly (SCI, DM1 and CVD), and lethal (CVD) or progressive (DMD, DM1). Innovative and experimental treatments are available in the field of regenerative medicine for all four diseases, but for some conditions there are other, more or less established, treatment options, which allow a person with the condition to lead what is regarded as an “almost ‘normal’ life” (DM1, CVD), while individuals with SCI an DMD are generally presumed to look to medical innovation, including regenerative medicine, for medical cures. As a matter of course, the perceptions and experiences of different diseases vary, but during field research, we found that there are also differences among individuals with ostensibly the same condition. By comparing individuals with different and similar conditions, we aim to shed light on what brings individuals to participate in clinical trials and travel abroad for experimental treatment.

According to Georges Canguilhem (1989) it is the experience of suffering, not normative measurements, that shapes ill health. Ill health should not be confused with ‘abnormality’, as disease conditions can be seen as part of ‘normal life’, and as a person with a disability can lead a ‘normal’ life (Canguilhem, 1989, pp. 200–201). So what does lead some persons with a disability to seek risky, unauthorised treatments to achieve ‘normality’ but not others. In Foucault’s work, dominant medical norms establish what is normal in modern society. Thus, persons with ‘disabled’ bodies do not fulfil social norms and are perceived as ‘unnatural’, which makes it, for instance, hard for them to find employment. In societies that rule not through violence, but through ‘free will’ and ‘norms’, normalisation is delegated to state and non-state institutions, which engage in what Nikolas Rose calls the “responsibilisation” of the population in advanced liberal democracies. It is not violence, sanctions or force that underlie normalisation here, but political discourse and individual choice linked to responsibility, free will and civil rights (Rose, 2007). In such democracies, individuals are expected to take responsibility for their health through free choice between option that public discourses define as ethical (Callon and Rabeharisoa, 2004).

Normalisation and responsibilisation play an important role in the lives of people with a disability. In democratic societies facilities exist that allow them to find a niche as a ‘normal’ individual with a disability. However, when it comes to options outside frameworks that define the norm, such as refraining from recommended ‘normal’ treatment or opting for risky and experimental medical treatment, our research suggests that somatic identity – the social experience and awareness of somatic lacking/wholeness - is crucial. To better understand this kind of decision-making, we need to gain insight into the experience of ‘lacking’ among persons with a disability when confronted with experimental treatment options.

Method

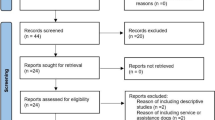

Between April and July 2014, Masae Kato interviewed fourteen individuals with chronic SCI, eight with DM1, three with CVD and eleven with DMD. Margaret Sleeboom-Faulkner interviewed four members of the Japan Spinal Cord Foundation (JSCF hereafter) and one individual with DM1. All interviews were semi-structured and lasted between 1 and 2 h. In conducting the field research, we first approached leaders of organisations for SCI, DMD and DM1, which connect various patient networks in the country. Organisations of SCI and DM1 were relatively accessible compared to those of other diseases, in that members of both are active in updating their websites, hold regular meetings and have a contact person. In general, leaders of the visited health organisations are aware of available medical treatments, both nationally and internationally, including methods of rehabilitation and regenerative medicine. To the best of our knowledge, there is no organisation for individuals with CVD in Japan. We were introduced to individual patients with CVD by medical specialists. The organisation for DMD is led mainly by parents of individuals with DMD, but we spoke with the latter directly. The snow-ball method generated further contacts. Interview questions related to a wide range of topics, including needs, financial conditions, local government support, their views on regenerative medicine, the current treatment they currently undergo and how they have been getting along with their condition.

We also interviewed over a dozen medical doctors specialised in these four conditions. The specialists provided an overview of the state of the art in the area of treatment and explained guidelines regarding regenerative medicine. We further spoke with over thirty scholars in the fields of biology, ethics and public policy to learn about health movements in Japan, as well as about their views on policies regarding regenerative medicine. Finally, we interviewed informants from various other backgrounds, including journalists specialised in stem cell ‘tourism’ (Song, 2010). We also attended symposiums and meetings related to these diseases and to regenerative medicine, and went to health-group meetings that discussed group activities, new therapies and administrative and financial matters.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to make a full comparison between the ways in which the symptoms of the four diseases are experienced in Japan, but we have tried to provide a brief overview of the available infrastructures, facilities, socio-cultural environment and nature of the conditions to shed some light on the contexts in which persons with a disability or condition make decisions about seeking innovative and experimental treatment.

Although the number of interviews with persons with the four diseases is not representative of populations of individuals with the four conditions in Japan, in-depth interviews with them are intended to generate insight into the relation between seeking experimental and innovative treatment, and self-perception, identity and notions of normality. As far as we know, no other research has compared the pursuit of experimental treatment from the points of view of individuals with different conditions. We hope, first, to contribute new insights into the variety of needs of people with four different conditions, including the search for cures; second, to shed further light on the notion of normality on the basis of these insights and third, call attention to the role of somatic identity, which we define as the social experience and awareness of somatic lacking/wholeness – in the daily-life experience of persons with a disability.

Next we discuss the views on experimental treatment of persons with the four conditions, after which we summarise our findings in relation to normalisation in the conclusion. We adjusted our use of the notion of ‘patient’ to the way in which our interviewees felt about themselves. This means that we used the word ‘patient’ when referring to those who identified with the idea of ‘receiving medical treatment’ as essential to their life; in situations where receiving medical ‘treatment’ was not relevant, we refer to ‘individuals or persons with a condition’. Using a similar principle, we either refer to ‘patient organisation’ or ‘health organisation’. The names of interviewees cited in this article are all pseudonyms.

Four conditions

Persons with the four conditions forge different views of normality and experience it differently. We argue that although normalisation figures importantly in the lives of many individuals with the four conditions, somatic identity is crucial to the extent to which patients seek treatment, and define their sense of normality.

Spinal cord injury

This section on SCI illustrates how interviewees with SCI imagine themselves as somatically lacking vis-a-vis dominant norms in society. Acceptance of the self as having a disability is problematic. This is expressed in the importance of and motivation to get back what is lost.

All the SCI interviewees are chronically disabled, with an average of 12 years, the longest 40, and the shortest 1 year. SCI is officially defined as a disability (障害) in Japan, meaning that local governments supply a pension for them (障害者年金) and their carer. The amount of pension and the number of hours of daily care depend on the severity of the disability, as well as the regulation of local governments. On average interviewees received some €800 per month, which many consider as insufficient. Some have jobs at a disabled people’s office, which tops earnings with some hundred euros a month. When injured at work, individuals with SCI are eligible for industrial accident insurance (労働災害保険). They can claim expenses for a disability-adjusted car; disability aids, such as wheelchairs, are paid by the government. Medical expenses are discounted both for individuals with a disability and family members.

When the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) was opened by Professor Yamanaka’s research group in 2007 at Kyoto University, SCI and DM1 were on their agenda as treatment targets. The aim was to move from basic research to clinical application within 10 years. Currently, CiRA is building a cell bank with a stock of various types of iPS cells for application to individuals with SCI within 6 months of injury – to prevent chronic damage. In June 2014, a team led by Okano Hideyuki at Keio University started a clinical trial to examine whether initiating treatment soon after SCI can help to ease paralysis and other conditions (The Japan Times, 2014). Okano’s team is leading research on regenerative medicine to treat SCI, supported by the JSCF. In June 2014, JSCF donated 5 million yen (€37,000) to CiRA to support iPS research (interview, leaders of JSCF, April 2014). So far, main treatment options for SCI patients are rehabilitation, massage and physiotherapy to improve physical functions.

Among the individuals interviewed, those with SCI expressed the greatest expectation of innovative treatment in the field of regenerative medicine, but they were careful in the way they expressed hope, as they know that, once chronic, spinal cord damage is hard to cure, and forthcoming clinical applications only enrol patients within 6 months after injury. Nevertheless, a 2014 symposium of the JSCF was entitled “Walk again: Challenges for Chronic Patients”, indicating high hopes for a cure. As many people with SCI engage in sports before their injury and often become disabled early in life, the inability to engage in some physical activities was poignant, often mentioned in the context of the wish to ski in the mountains or play rugby again. Interviewees said that SCI “took the joy out of my life” (interview, 22 April 2014), “totally damaged my life overnight” (interview, 27 April 2014) and “is the greatest regret in my life” (interview, 9 May 2014). Patients’ expectations of regenerative medicine should be understood in this context. Patients say, “even if iPS cells would turn into cancer cells, I would still try it. Cancer is more acceptable than not being able to walk” (interview, 9 May 2014) and “if I could ever walk again I would not mind dying” (interview, 22 April 2014). For SCI patients, regenerative medicine, especially iPS research, is what “might give life once again” (interview, 27 May 2014) and what “might enable the world where SCI patients do not exist any longer” (interview, 9 May 2014). Single patients under the age of 39 (5/14) said that marriage and having children were their dreams, and these dreams were narrated as part of their expectations from regenerative medicine. Ms Sato said,

A generation ago, SCI patients were infertile because of paralysis. But nowadays it has become possible for some SCI patients to have children with the help of infertility treatment. But it cannot help me yet… Among patients, there is an atmosphere that those who are married and have children are the winners. …I hope that regenerative medicine can solve this problem.

Between 2003 and 2007, among individuals with the four conditions, only those with SCI engaged in stem cell tourism to China. The treatment used Olfactory Ensheathing Glia cells, or OEGC, obtained from the brains of aborted foetuses. Although the treatment was generally controversial among scientists and in the mass media (NHK, 2005; Sakagami, 2013; Tamai and Kasuga, 2009), thirteen SCI patients travelled there (interview, 22 April 2014). We interviewed two of them. Mr Saiki, who travelled there in 2005, said,

One cannot just wait. If you want to walk again, you must not just follow others. I chose to undergo the treatment despite its negative reputation. (Interview, 9 May 2014)

Ms Sawa, who also went to China in 2005, said,

One must not have judgment about the treatment because it involves China. You have to be open to change and innovation, if you want to fulfill your dream. (Interview, 27 May 2014)

Both spent approximately 3 million yen (some €25,000) for the whole trip, including treatment. Neither was financially at a deadlock nor particularly well-off. Mr Sawa said that he decided to travel for treatment because all the treatment costs, including rehabilitation and wheelchairs, were covered by his labour insurance and the state health insurance, though he would have paid for the treatment himself.

Currently, SCI patients expect more from iPS cells and no longer travel abroad, as hardly any positive results were witnessed from OEG cells interventions. Among our interviewees, those with SCI and their partners were the most willing to try unestablished scientific interventions. Ms Sagami, whose husband sustained SCI a year ago, says,

I regularly participate in JSCF’s meetings, because I do not want my husband to miss any chance to participate in clinical trials. If there is a chance, and even though the therapy is scientifically not fully established, I will be the first go. (Interview, 25 April 2014)

During field research, individuals with SCI and DMD showed remarkable contrast in their attitude towards disability and the wish to be cured. Individuals with both conditions are confined to a wheelchair, but those with DMD were born with their condition, while those with SCI acquired the condition suddenly. Those with SCI clearly showed more reluctance to accept their disability. Individuals with SCI reported that for many years after the injury they were depressed, became violent, did not go out of the house at all, avoided seeing their body in mirrors or meeting friends they had known before injury. Although many individuals with SCI have established a balance in their lives, and have found a way to get along with their disability, a common narrative among them was, ‘I wish I could walk again before I die’. While it is possible for persons with SCI to imagine walking, because they know what it is, as we discuss below, it is an unreal notion for most individuals with DMD.

Individuals with SCI are aware that their condition is difficult to treat once it becomes chronic, and that, if there is any treatment possible at all, it will not be in the near future. So almost all the persons with SCI we interviewed – even those who travelled to China – indicated that while they expect some positive developments from regenerative medicine, they do not want to become obsessed by the idea of being cured, and would rather enjoy life as it is for now. For instance, our interviewees with SCI engaged in sports activities, travelled both within Japan and abroad and invested time into making new friends.

The narratives of interviewees with SCI are of people that want to return to ‘normal’ life, life without limitations. They regard themselves as severely limited, which is especially poignant as their life expectation and mental ability are usually regarded as ‘normal’. Of course ‘normal’ here is the dominant mean – and therefore does not mean without limitations. Scientists receive much support from the SCI association to find a ‘cure’, and to help them to return to ‘normal life’. As many persons with SCI are not patients (in need of regular treatment by a medical professional), ‘being a patient’ denotes receiving treatment, which implies a possibility of getting better. The dreams and activities of our interviewees with SCI belong to a previous life, often cut off in bloom: remembering what it is to walk makes it hard to accept a different bodily self, both physically and mentally; not having a choice causes a sense of deprivation, rendering a sense of enjoying a full life impossible. Even though jobs can be found and pensions are provided, somatic normality among people with SCI experience a continuous sense of lacking. Those among our interviewees with SCI that are prepared to take considerable risk often do so to regain their former life and its meaning.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Our interviewees with duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) are much less cure-oriented than those with SCI. We illustrate how identity plays an important role in the experience of normality. DMD may be regarded as a condition entailing many disabilities, but in interviews, persons with DMD express a strong sense of self and their own normality, regardless of what society and science may consider ‘normal’.

DMD is officially defined and referred to as an incurable disease (難病) in Japan. Similar to individuals with SCI, those with DMD also receive a pension of approximately €800 per month. While some individuals with SCI receive a labour pension if injured during working hours, individuals with DMD usually have no employment history, and live on their pension and parents’ financial support. The average age of our DMD interviewees is 21, and they live with parents or in institutions for people with disabilities. Traditionally, their mothers take care of them, but in 2005 the welfare system changed so that persons with DMD can secure carers from local governments (see also Welfare and Medical Service Network System, 2016). Persons with DMD are usually allocated a relatively high number of hours of care, up to 20 h a day.

So far, there is no cure for DMD, though machines and medicine can prolong lifespan, including cough assistance machines, wheelchairs and cardiotonic drugs. In the field of regenerative medicine, DMD research promises fundamental improvement or cures, albeit not in the near future. Most recently, a study was published on gene therapy for DMD using programmable nucleases to restore the dystrophin protein (Lin et al, 2014). Furthermore, exon skipping, a form of gene therapy, is on clinical trial, aiming to lighten symptoms of Duchenne to the level of that of Becker (Nippon shinyaku, 2013).

Having had symptoms at an early age, most of our interviewees with DMD expressed a mild desire to be cured. More than half of them said walking was not a reality, and they doubted that regenerative medicine would enable them to do so. DMD is a disease whereby an individual progressively loses the ability to engage in activities over the course of life. Many persons with DMD express frustration on this point and fear for the future. A young boy who loves playing the piano expressed how disappointing it was to confront the fact that he could no longer play. For some time, he avoided having the piano in sight. Nevertheless, we found that individuals with DMD dealt with their condition in a composed manner. Mr Masaki said,

I have lost the ability to do one thing after another, and this is a fact. There is no judgment about it. It is a fact. The symptom of DMD is a sequence of these facts, no more and no less. DMD means aging comes early. (Interview, 16 May 2014)

Another person with DMD, Mr Momose, said,

I can imagine SCI patients would wish there had been no accident that caused the injury. But in our case, we are born with this physical condition. It is myself. Although I believe Yamanaka is a great scientist, I cannot imagine anything can change our genetic condition. (Interview, 16 May 2014).

Many of our DMD informants expressed an obstinate reluctance to perceive their disability in a negative manner. A person with DMD who runs his own non-profit organisation (NPO) that aims to enhance a barrier-free life for sufferers said,

I feel content with my activities in the organisation, allowing me to improve social conditions for disabled people. Without my disability, I am no longer myself. I lived my life based on the fact that I have DMD. I would be at a loss and without a purpose in life without DMD. … I think our genetic condition is a property of humankind (jinrui no isan). I do not agree with any attempt to erase such genetic sequences. (Interview, 11 May 2014)

This informant views his disability in a positive way, as being an integral part of his being. Calmly dealing with the disease and obstinately resisting the idea to perceive DMD as something to be removed or changed, this tone of argument reminds us of Japan’s disabled people’s movement’s discourses against eugenics (Matsubara, 1998). Narratives of persons with DMD on the idea of ‘being cured’ and their expectations from regenerative medicine need to be understood in the context of eugenics in Japan.

The introduction of the National Eugenic Law dates back to 1940. In 1948, this law was revised into the Eugenic Protection Law, a stricter form concerned with “preventing the birth of inferior descendants” (Kato, 2009), articulating legal procedures to sterilise people with genetic disorders. This was part of the government’s policy to re-build Japanese society by enhancing the quality of the population after the devastation of the war. Some 16,000 people were sterilised between 1949 and 1994 in the name of ‘eugenic operation’ (Shim-bun, 1996). After amniocentesis was introduced into obstetric practices in the 1960s, the disabled people’s movement started to keep an eye on policies and regulations of prenatal testing. Although the Eugenic Protection Law was revised in 1996 and legal procedures for eugenic operation are no longer in the law, reproductive genetic technologies remain high on the agenda of the disabled people’s movement in Japan.

Since 2004, DMD is classified as a severe genetic disorder in Japan, and it has been a target of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). Individuals with DMD contend that if Japan’s society for obstetricians (日本産科婦人科学会), an authority in the field, legitimises the elimination of embryos with DMD before embryo transfer, it is an official denial of the value of life of people with DMD, or a practice of eugenics (Mizoguchi, 2001; Okamoto, 2001). The notion of our interviewees with DMD is to accept the disease as part of themselves, rather than trying to get rid of it. This contrasts sharply with the perspectives of people with SCI regarding their disability and the determination of ‘finding a cure’.

As a genetic disorder, DMD has not just biological but also socio-cultural implications for reproduction. None of our interviewees had partners, were married or had children. Nor did persons with DMD regard reproduction as realistic. This is not difficult to imagine, as they are usually young, and have had symptoms since childhood. But these factors are augmented by the fact that discrimination against genetic disorders exists in Japan. Marriage is usually an issue of bringing together two family lines rather than two individuals, and if a genetic disorder is introduced to the mixture through one family line, the other regards it as a contamination of theirs (Kato and Sleeboom-Faulkner, 2009). Related to this, the birth rate of individuals with DMD is decreasing in Japan (Kondo, 2016), which has been made possible through knowledge of genetic inheritance – after genetic counselling, female carriers tend to terminate pregnancy (Kato and Sleeboom-Faulkner, 2009; Kondo, 2016).

The physical conditions and needs of people with DMD are particular to this group and involve a more conservative attitude towards what is possible in the present. People with DMD often struggle with physical exhaustion in everyday life. This contrasts with people with SCI, who generally do not suffer from chronic exhaustion. Furthermore, engagement in support for the development of innovative medicine does not gain momentum due to the young age and often dependent lifestyle of persons with DMD. Additionally, the causes for and types of muscular dystrophy differ greatly, so that collective prioritisation of certain types of innovation is difficult (interview Medical Doctor specialised in DMD 24 April 2014). Regarding travelling abroad, most persons with DMD said that travel by airplane, even for a vacation, is complicated and exhausting because of their physical condition: it requires carers for many hours a day, a wheelchair and machines such as lifts. This contrasts with individuals with SCI, who are also dependent on a wheelchair, but travel abroad on vacation to do sports and for controversial treatments. Meetings of the DMD organisation do not focus much on political lobbying with pharmaceutical companies, but tend to be informal meetings for discussing how to improve the everyday needs of people with DMD.

Nevertheless, interest in new medicine is not entirely non-existent among persons with DMD. There is interest in treatment that can stop progress of the condition or alleviate symptoms. And although our interviewees tried to minimise medicine, all were aware that survival depends on it. The DMD organisation takes great interest in new medical developments, but follows its possibilities with a critical eye rather than with great expectations and hope.

Most DMD persons are also patients, in the sense of being under medical treatment. But, compared to people with SCI, they seem to accept their condition, and do not necessarily always regard themselves as patients. Interviewee narratives and discussion on the value of human life in Japan indicate that people with DMD have developed their own sense of normality next to an awareness of dominant notions of normality. Despite somatic limitations and a limited life span, persons with DMD have developed a somatic identity that cannot but accept DMD as the norm. Although (and perhaps because) genetic discrimination in Japan discourages reproduction in people with genetic disorders, Japan also has a strong activist culture against genetic discrimination, which is reflected in the IVF and PGD regulation that prohibits selection on the basis of disease (Kato, 2009). Nevertheless, most persons with DMD and the DMD health movement are interested in facilities that can support their daily lives rather than in a ‘cure’. Due to their dependence on carers, persons with DMD often regard themselves both as patient and as disabled, but they also regard themselves as whole persons important to human kind. In fact, some interviewees pointed out that being disabled emphasises their humanity.

Type 1 diabetes

Compared to SCI and DMD, in Japan DM1 is regarded as a disease (疾患) rather than as a disability: as long as those with DM1 inject insulin with discipline, they do not appear to be different from any other healthy person, and they seem to lead a ‘normal’ life. For this reason, unlike individuals with SCI and DMD, those with DM1 do not narrate their disease in terms of being targeted by eugenics or suffering from social barriers. The narratives of our interviewees show how a somatic condition that allows ‘normality’ through discipline keeps them from experimenting with new medical interventions.

Parents of individuals with DM1 of under-twenty years of age do not have to pay a premium for health insurance to receive medical care. Patients with DM1 of 20 years and above pay a national insurance fee (€400 per year), and are reimbursed for 70% of their medical expenditure, just as is the case with ‘healthy’ Japanese citizens. A health check and insulin cost around €250 per month. However, at times of severe economic recession and high unemployment, some cannot afford to pay the national insurance tax. A person with DM1, active in the Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (IDDM) network, said that some 30 per cent of network members are not undergoing monthly health checks and do not receive insulin injections. It is a serious social problem that citizens cannot pay for insurance and cannot afford to see the doctor. Many persons with DM1, according to this person, fear kidney malfunction and becoming blind (interview, 24 May 2014). For individuals with the disease, there are no specific public services, no special pension plans, subsidies or carers. But if the condition is accompanied by complications, such as blindness or kidney failure, individuals with DM1 receive a pension for people with disabilities.

Unlike type 2 diabetes individuals, DM1 does not require following a strict diet, and taking insulin is the only treatment option because the body does not produce it. The disease often appears at a relatively young age (juvenile diabetes). The average age at the appearance of symptoms in our informants is 9, but onset is usually earlier. Children with DM1 and their parents all said that they were shocked to hear that they would have to inject insulin for the rest of their lives. For children, mothers are usually the main carers and some of them visit schools two to four times a day, to inject insulin and to measure the blood sugar. Two interviewees said that they had considered committing suicide when they were first diagnosed.

Having the disease restricts the lives of individuals with DM1 especially in two areas: reproduction and employment. Among our fourteen interviewees, seven started to have symptoms before the age of reproduction, while two said they gave up the idea of having children because of the disease. They were afraid their physical condition would deteriorate. Male interviewees were more optimistic about reproduction: three of them, all childless, wanted to get married and have children; two were not sure (one woman and one man). Among our fourteen interviewees, six were employed, three were housewives, three were looking for a job and two were students. Among those who work, two own a business, because of the discrimination they thought they would encounter during job-hunting; all individuals with DM1 said that they are avoided by companies. Companies fear they will have accidents and die on the job (interview, leader of a health organisation, 10 May 2016). About this point, a father of a child with diabetes aged 13 said, “their survival is actually a great proof of their trustworthiness. It requires discipline, punctuality, precision, and skill. Therefore, it is not right that companies avoid hiring them” (interview 28 May 2014).

So far, insulin injection and islet transplantation have been the only means to live with DM1. But in recent years, a number of studies have been conducted in the field of regenerative medicine, including regenerating the pancreas, islets of Langerhans (pancreatic cells which produce insulin) and pancreatic beta cells using iPS cells (Shanti, 2013; Japan IDDM Network, 2016). DM1 is high on the list of Yamanaka’s research team and the IDDM network aims for a ‘fundamental cure’ (根治 konchi) by 2025. For this, the network actively collects money and annually donates funds to researchers. To gain access to the fund, scientists have to formally submit a research proposal to the IDDM network, reviewed by a scientific committee internal to the network. Every year, three research projects are funded awards of €20,000 to €30,000, and they organise an annual scientific symposium for individuals with DM1, inviting scientists who present their research on DM1 and regenerative medicine (Interview, leader of a patient organisation, 10 May 2014; Japan IDDM Network, 2014, 2016). The leader of the group, a father of a child with DM1, is a scientist himself, which helps the organisation not only to approach scientists in the field of regenerative medicine and disseminate information on regenerative medicine, but also to organise scientific activities in a professional way.

Since DM1 was on the agenda of CiRA, ten patients expressed the wish to wait for treatment to become available in Japan. Unlike DMD, but similar to SCI, persons with DM1 are actively in favour of treatment, and express the desire to, some day, no longer have the need to inject insulin. Unlike the interviewees with SCI, however, seven out of the ten said they did not want to take the risk of undergoing a clinical trial, not even in Japan. Reasons they gave for this were: “as long as I accurately inject insulin, 90% of my life is the same as that of others” (interview, 28 May 2015), and “DM1 is not drastically lethal, unlike cancer” (interview, 16 May 2015). One individual with DM1 also said that, even when regenerative medicine is scientifically established in Japan, he would wait at least 1 year before deciding whether to try it (interview, 28 May 2015). Only one individual with DM1 said she might want to try a clinical trial if it fits her condition (interview, 10 May 2015). Three individuals with DM1 said that travelling abroad with the aim of undergoing experimental treatment is troublesome, due to the need to carry insulin, and the time difference, which complicates the regime of injecting insulin.

While for SCI patients regenerative medicine might be the only means to return to ‘normality’, for persons with DM1 regenerative medicine would not be essential to their health, because following a medical regime enables them to lead a ‘normal’ life. Although interviewees with DM1, unlike individuals with SCI, tended to have high expectations from regenerative medicine, they would wait until the treatment is well established before seeking it.

Thus, Mr Date (52), a successful businessman with DM1 says that he is interested in regenerative medicine, but will not participate in a clinical trial, not even if held in Japan. Having been a patient for over 30 years, Mr Date trusts his doctor who, he says, saved his life. Even if his medical treatment is not state of the art, and even if he dies from a medical error, he would have no regrets. Mr Date trusts and follows his doctor’s advice. In his view, the existing medical standard of treatment for individuals with DM1 in Japan, even without regenerative medicine, is of the world top level. He believes this because he witnessed foreign patients from the Middle East visiting his doctor, and he saw medical trainees from abroad at his hospital. Even though he expects regenerative medicine to yield results soon, he is convinced that he is already enjoying high-quality medical care, and sees no reason to try experimental medicine, let alone to travel abroad.

Another reason for individuals with DM1 hesitate to participate in clinical trials is that they worry that DM1 might reemerge because the medical intervention uses the patients’ own cells. Although individuals with DM1 expect regenerative medicine to enable life without insulin, they do not want to take the risk; they prefer to wait until the medicine is established. This contrasts with the narratives of individuals with SCI, for instance, who show greater preparedness to take high risk.

The somatic identity of persons with DM1 is shaped by great uncertainty. This potentially very serious condition develops at a relatively young age, but a ‘normal’ life is possible if adhering to a medical regime in a disciplined manner. The latent possibility of developing a severe condition makes developing a ‘normal’ social life – in the dominant normal sense – very difficult, bringing some to consider suicide. This leads us to argue that to Canguilhem’s negative definition of health as an absence of disease (Canguilhem, 1989) we should add the absence of latent conditions, as they affect a healthy social life, including employment, partner choice and self-definition. The conflicting possibilities that individuals with DM1 live with influence their decision whether to seek experimental treatment. Health organisations for DM1 support scientific research into innovative therapies, but not all individuals with DM1 are interested in participating in a clinical trial, being confident that they can get by with a strict intake of medication. Those among our interviewees who are interested prefer to stay in Japan, as travelling can be complex, and tend to want to go ahead only when the therapy has been proven safe and efficacious.

Cardiovascular disease

The somatic identity of the three persons with CVD interviewed was influenced by their experience of the phase of life they were in. Important is how they felt that their life so far related to the ‘normal’ life cycle, including having a family, employment and their physical condition. All felt that their condition had led them to be at odds with ‘normal life’. Although they generally welcomed a cure for their condition, the reactions to this possibility depended largely on the factors mentioned above.

Many of the problems associated with cardiovascular disease are related to the process of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is a condition that develops when plaque builds up in the walls of the arteries. This build-up narrows the arteries, making it harder for blood to circulate. If a blood clot forms, it can stop blood flow and cause a heart attack or stroke. According to the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, a heart attack leads to death in 20 percent of cases, and most sufferers die within 1 hour of the attack (Yasuda, 2012). However, although survivors may have a good chance to return to ‘normal’, most require medication, diet and an exercise regime. Some patients remain in a weak condition and may require an artificial heart (人工心臓). Similar to DM1, as long as individuals with a heart condition are disciplined in their lifestyle and observe a suitable medical regime, they do not appear to be different from other healthy persons. A problem is, however, that individuals with a heart condition do not always notice the progress of the disease.

In Japan, individuals with a heart condition generally do not receive a special pension or care from the government, although some particular forms of CVD, such as cardiomyopathy, are officially defined as a disability in Japan, meaning that persons with CVD receive a pension. When annual medical costs are excessive in comparison to annual income, under certain conditions, part of the costs are reimbursed by the local government through “catastrophic medical expense coverage” (高度医療費制度).

A new treatment of regenerative medicine for myocardial infarction, which uses cell sheet engineering, has been applied clinically to regenerate heart muscle. It was developed at the Institute of Advanced BioMedical Engineering and Science Tokyo Women’s Medical University together with Osaka University. The heart sheet technology has been conditionally approved as clinical treatment (Okano, 2012), but at the time of fieldwork it was still undergoing clinical trial (Sakai and Okano, 2013; Leibing et al, 2016). Individuals with a serious heart condition could be enrolled in clinical trials using cell sheets if no other treatment was available. Treatment costs for the clinical trials were covered by the University Hospital and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, but patients had to pay for periodic check-ups before and after the operation, as well as the necessary medicines. Among our interviewees, two males with cardiomyopathy participated in clinical trials, and one, who had suffered a stroke, decided not to, although he had been offered this option. All three were in critical condition after their heart attack.

Factors considered in their decision to participate in the clinical trial were employment, family, phase of life and physical condition. Mr Chiba (36) and Mr Chino (53) said they participated because they wanted to remain employed, alleviate the symptoms of the disease and prolong their life span. Right before the operation took place, both were critically ill and did not expect to live more than 1 year. At the time of interview, Mr Chiba had returned to work for two months, while Mr Chino was still looking for a job. Finding employment, he felt, was hampered by employers’ fears that they might cause an accident during working hours. Mr Chino is no longer considered young and is not desirable in the job market. For Mr Chiba, the phase of life he was in partly motivated his decision to participate in the trial, as he wished to start a family. Mr Chino, however, was motivated by the opposite situation of not having family members. He said, “I was not afraid of the trial because if it fails, no one will be left behind” (interview, 11 June 2014).

Mr Chikuda (62), who had had a stroke in the previous year, chose not to participate in the clinical trial. Although he recovered miraculously, Mr Chikuda was applying for early retirement. He said,

The process of the trial would be too much for me, I thought. The stress would be bad for my heart….My two children are grown up, and I have worked all my life. Now I feel it is reasonable … My priority is to maintain my life… I cannot move around like I could before, but I accept it. (Interview, 11 June 2014)

The factors important to the decisions of Mr Chiba and Mr Chino – employment, family and phase of life – also underpin the decision of Mr Chikuda: he believes that he has worked enough, his children are grown up and he feels that he should not have to push himself any more. Their decisions were not taken under pressure of a patient or health group, as none of the three belonged to one: Mr Chiba said that he did not like to talk openly about his disease, not even with others with a heart condition; Mr Chino said it would be depressing to discuss physical conditions with others and Mr Chikuda said that even managing daily life is exhausting, let alone participating in a patient or health group. All said that they had received information on the clinical trial from their medical doctor during a periodical check-up. The three persons with CVD gave the impression of feeling tired and being in need of rest due to their physical conditions, and perhaps also because CVD was acquired at a relatively advanced age.

Persons with CVD prefer to undergo treatment in Japan. None had considered travelling abroad for treatment. According to one medical doctor, most individuals with a heart condition are in their fifties or over when they have their first heart attack, and it is more appealing to them to control their diet and do exercise than to travel abroad. Travelling, being wearisome, is considered as part of the costs and difficulties of seeking treatment. Actually, three interviewees said that even collecting information about treatment within Japan is energy consuming, and they would rather depend only on their own medical doctors. In addition, individuals with CVD expressed the view that the treatment cannot bring back the life they led before the heart attack, and that any clinical trial would only stabilise or ameliorate their condition to some extent.

Our interviewees with CVD were not caught up in the hype of medical tourism. For the two with a bleak prognosis, it was important to find treatment, but they had not considered going abroad. They just took the opportunity of participating in the heart sheet clinical trial, which they had heard about through their cardiology doctors. They trusted information, had no need to become a member of a patient or health organisation; their physical condition made travelling difficult for them anyway. The one who chose not to participate in the clinical trial planned to retire, even though he had recovered substantially, indicating that he felt that he had worked long enough. Although full recovery was not expected, one of the men hoped to later have a full reproductive life.

Conclusion

Most studies on the socio-economic factors relevant to why people participate in experimental treatment in regenerative medicine focus on individuals that have decided to undertake treatment, missing the opportunity to compare them with those who decide against. They also have not made a systematic link between decision-making and the socio-economic conditions of individuals with different disabilities and disease conditions. This article, however, has explored the relation between four medical conditions and the search for experimental treatment and notions of normality in Japan, focusing on somatic identities of individuals in daily-life experience.

Although we do not claim that our interviewees represent all people with SCI, DMD, DM1 and CVD in Japan, the differences and similarities of narratives around normality suggest that decisions to seek experimental treatment depend not so much on dominant notions of normality, as on the experience of somatic lacking/wholeness, which we argued is rooted in a person’s somatic identity and its embedding. The narratives of interviewees indicate that the history of the somatic self is fundamental to the formation of the social identity of individuals with different disease conditions: narratives indicate that persons with SCI, whose former, often, active and relatively young life had been interrupted, tend to feel incomplete and compare themselves to the dominant notion of normality; the narratives of persons with DMD, who indicated that they are aware of their limitations compared to other humans, do not imply that these limitations cause them to diminish their sense of normality and worth as part of humankind; the narratives of persons with DM1, who find out at an early age that their lives depend on a strict medical regime, show how they contend with latent problems and uncertainties in relation to dominant notions of normality, while the narratives of those with CVD indicate that they value themselves in the light of the ‘normal’ life cycle (Table 1).

The narratives showed that various factors related to the ‘normalised’ life cycle play a role in seeking experimental treatment among persons with a disability and their relations: experiences of suffering, life expectancy, financial means and the availability of alternative therapy options are of great importance.

It has been argued that ‘normalisation’ plays a major role as a driver to ‘self-correction’ among people with disabilities. Thus, the image of a ‘disability’ and genetic ‘diseases’ in society, the source of and trust in information about experimental treatment (GPs, hospitals, patient movements, agencies, websites) and dependence on normalised state authorities and private institutions are all factors that to some extent play a role in the motivation to adjust health conditions to the ‘dominant normal’. All in all, however, the narratives also indicate that the robustness of the somatic identity of people with a disability is underestimated. We saw that while interviewees with SCI were not subjected to ideas around eugenics, they were prepared to undergo experimental treatment to ‘return’ to their pre-injury physical condition. Interviewees with DMD, however, who are subjected to eugenic discourses, are sensitive to ideas that deny their value as humans. It is not just because genetic disorders are disliked in society that interviewees with DMD reject the idea of ‘self-correction’ as their responsibility; it is the somatic experience that has stabilised their socio-political sense of identity as a valuable self. In the case of interviewees with DM1, we saw that the ever-present psycho-physical threat of disease when failing to observe the medical regime makes for a precarious self-identity. Treatment is only worthwhile when the pathway to ‘normality’ is safe and sound. For our interviewees with CVD, however, experimental treatment was worthwhile seeking in the context of criteria inherent to a ‘normal’ life cycle.

Our findings suggest the need for further research on notions of normality, responsibilisation and discipline and hyping. We found that Canguilhem’s negative definition of normal health in terms of the absence of disease should be extended to include references to the absence of latent disease conditions and the absence of high risk of developing a condition. Such ‘normal health’ we referred to as dominant health. Although people with some conditions – especially those with SCI and DM1 among our interviewees – express the need to conform to a ‘dominant normality’, others – such as those with DMD among our interviewees – do not take the dominant normal into account, regarding DMD as one of many conditions inherent to humanity. In addition, the concept of the ‘normal life cycle’ – expressed especially among those with CVD, DM1 and SCI – is an important frame of reference for the decision-making regarding medical intervention. Notions of ‘normal’ life expectancy influence the decision-making of our interviewees, leading some to conclude that they are missing out, had enough or need to catch up.

The existence of different experiences of dominant normality also requires a review of the notions of responsibilisation and discipline. People with disease conditions may be expected to look after themselves and make decisions along the lines of what are publically recognised notions of normality and bioethics. Those whose identity is forged by such dominant normality may feel inadequate, undervalued or alienated when unable to adopt these. However, the narratives of individuals with four different conditions in Japan shows that in many ways, it is the social experiences of a particular somatic history that is crucial to whether individuals feel they need to self-define in terms of the dominant normality or of other, often competing, normalities. Thus, we saw that our interviewees with DMD are widely supported in their own sense of normality and have been successful in changing the regulation on embryo selection in Japan. The failure to participate in ‘responsible’ decision-making and self-discipline can have repercussions, but it some cases it can also lead to the recognition of broader values and their normalisation, actually liberating individuals from decision-making.

The availability of ‘high risk’ and the ‘hyping’ of innovative biomedical therapies also needs to be considered in this context. In the accounts of interviewees, the decision of whether to have experimental treatment depends on the somatic identity of people and their notions of ‘a life worth living’. Although decisions are based on discourses of medical possibilities, availability and affordability, our narratives show that it is the somatic experiences and identities if individuals that impregnate these terms with meaning in the context of their perspectives of what are normal lives, life cycles and life values.

References

Bharadwaj, A. (2013) Subaltern biology? Local biologies, Indian odysseys and the pursuit of human embryonic stem cell therapies. Medical Anthropology 32(4): 359–73.

Bianco, P. and Sipp, D. (2014) Selling help not hope. Nature 510: 336–337.

Brown, N. and Michael, M. (2004) A sociology of expectations: retrospecting prospects and prospecting retrospects. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 15: 3–18.

Callon, M. and Rabeharisoa, V. (2004) Gino’s lesson on humanity: genetics, mutual entanglements and the sociologist’s role. Economy and Society 33(1): 1–27.

Campbell, F.K. (2012) Stalking ableism: Using disability to expose ‘abled’ narcissism. In: D. Goodley, B. Hughes and L. Davis (eds.) Disability and Social Theory. New Developments and Directions. Basingstoke: Palgrave and MacMillan, pp. 127–142.

Canguilhem, G. (1989) The Normal and Pathological. Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press.

Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA). (2015) What are iPS cells? October 2015, https://www.cira.kyoto-u.ac.jp/e/faq/faq2.html, accessed 20 October 2016.

Chen, H. and Gottweis, H. (2013) Stem cell treatments in China: Rethinking the patient role in global bio-economy. Bioethics 27(4): 194–207.

Davis, L.J. (2002) Bending over Backwards: Disability, Dismodernism, and Other Difficult Positions. New York: New York University Press.

Foucault, M. (1994) The subject and power. In: P. Rabinow and N. Rose (eds.) The Essential Foucault. New York: The New Press, pp 126–144.

Foucault, M. (2003) Abnormal: Lectures at the College De France 1974–1975. Arnold I. Davidson (ed). Picador: New York.

Ho, A. (2008) The individualist’s model of autonomy and the challenge of disability. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 5: 197–207.

Hyun, I. 2013. Therapeutic hope, spiritual distress, and the problem of stem cell tourism. Cell Stem Cell 12(5): 505–507.

Japan IDDM Network. (2014) Nihon IDDM Network symposium in Tokyo (Japan IDDM Network symposium in Tokyo). http://japan-iddm.net/sympo_tokyo_2014/, accessed 20 October 2016.

Japan IDDM Network. (2016) Nihon IDDM network saiensu forum (Japan IDDM Network Science Forum). http://japan-iddm.net/sympo_2016_saga/, accessed 20 October 2016.

Kato, M. (2009) Women's rights? The politics of eugenic abortion in modern Japan. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Kato, M. and Sleeboom-Faulkner, M. (2009) Culture of marriage, reproduction and genetic testing in Japan. Biosocieties 4(2–3): 115–127.

Kim, L. (2012) Governing discourses of stem cell research: Actors, strategies, and narratives in the United Kingdom and South Korea. EASTS 6(4): 497–518

Kondo, H. (2016) The current situations of medicine for muscular dystrophy (Kinjisu iryō no genjō). http://www2b.biglobe.ne.jp/~kondo/dmd/genjou.htm, accessed 20 October 2016.

Kyoto University News. (2016) CiRA establishes implementation framework for clinical research on age-related macular degeneration using iPS cells (6 June). News: Research and Collaboration, 22 August, http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/research/events_news/department/ips/news/2016/160606_1.html, accessed 20 October 2016.

Leibing, A., Tournay, V., Menezes, R. A. and Zorzanelli, R. (2016) How to fix a broken heart: Cardiac disease and the ‘multiverse’ of stem cell research in Canada. BioSocieties 11(4): 435–457.

Li, H.L., Fujimoto, N., Sasakawa, N., Shirai, S., Ohkame, T., Sakuma, T., Tanaka, M., Amano, N., Wataname, A., Sakurai, H., Yamamoto, T., Yamanaka, S. and Hotta, A. (2014) Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Report 4(1): 143–154.

Mason, C. and Dunnill, P. (2008) Editorial: A brief definition of regenerative medicine. Regenerative medicine 3(1): 1–5.

Matsubara, Y. (1998) The enactment of Japan’s sterilization laws in the 1940s: A prelude to postwar eugenic policy. Historia Scientiarum 8(2): 87–201.

McMahon, D. and Thorsteinsdóttir, H. (2010) Regulations are needed for stem cell tourism: Insights from China. The American Journal of Bioethics 10:5, 34–36.

Mikami, K. and Stephens, N. (2016) Local biologicals and the politics of standardization. Making ethical pluripotent stem cells in the United Kingdom and Japan. BioSocieties 11(2): 220–239.

Mizoguchi, N. (2001) ShN. (Shōgai mo hitotsu no kosei (Disability is also a characteristic). In: H. Kaiya and the Japan Muscular Dystrophy Association (eds.) Idenshiiryō to seimeirinri (Genetic Medicine and Bio Ethics). Tokyo: Nihonhyōronsha, pp. 65–70.

NHK. (2005) Chūzetsu taiga (saibō) riyō no shōgeki (Shocking News about the use of aborted foetuses). NHK special, http://www7a.biglobe.ne.jp/~hakatabay/TVsyoukai252.pdf, accessed 20 October 2016.

Nippon Shinyaku. (2013) Kokunaihatsu no anti-sense kakusan iryōhin to shite Duchenne gata kinjisu torofii chiryōzai no rinshō shiken kaishi (The first clinical trial starts with Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients), http://www.nippon-shinyaku.co.jp/company_profile/news.php?id=1960, accessed 20 October 2016.

Novas, C. (2006) The political economy of hope: Patients’ organizations, science an biovalue. BioSocieties 1: 289–305.

Novas, C. and Rose, N. (2000) Genetic risk and the birth of the somatic individual. Economy and Society 29 (4): 485–513.

Ogbogu, U. Rachul, C. and Cauldfield, T. (2013) Reassessing direct-to-consumer portrayals of unproven stem cell therapies: is it getting better?. Regenerative Medicine 8:3: 361–369.

Okamoto, E. (2001) Fujiyūnahito ni yasahī shakai o (For a compassionate society for disabled people). In H. Kaiya and the Japan Muscular Dystrophy Association (eds.) Idenshiiryō to seimeirinri (Genetic Medicine and Bio Ethics). Tokyo: Nihonhyōronsha, pp. 71–72.

Okano, T. (2012) Saibō sheet no kiseki (Miracles caused by cell sheets). Tokyo: Shōdensha.

Patra, P. K. and Sleeboom-Faulkner, M. (2011) Recruiter-patients as ambiguous symbols - bionetworking and stem cell therapy in India. New Genetics and Society 2: 155–167.

Petersen, A., Munsie, M., Tanner, C., MacGregor, C., and Brophy, J. (2017). Stem Cell Tourism and the Political Economy of Hope. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Petryna, A. (2002) Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rose, N. (2007) The Politics of Life Itself. Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sakagami, H. (2013) Saisei-iryō no hikari to yami (Lights and shadows of regenerative medicine). Tokyo: Koodansha.

Sakai, H., and Okano, T. (2013) Nihonhatsu, sekaihatsu no ‘saibō sheet kōgaku’ gijutsu ni yoru saisei iryō (First in Japan and in the world: Regenerative medicine with cell sheets). Tokugion, 271: 44–52. http://www.tokugikon.jp/gikonshi/271/271tokusyu6.pdf, accessed 20 October 2016.

Sakai, M. (2014) Patients’ commitment in a clinical trial program: Examining Japanese regenerative medicine for spinal cord injuries. Core Ethics 10: 97–108.

Salter, B, Zhou, Y. and Datta, S. (2015) Hegemony in the marketplace of biomedical innovation: Consumer demand and stem cell science. Social Science & Medicine 131: 156–163.

Shanti. (2013) Ichigata tōnyōbyō to iPS saibō ni tsuite (About DM1 and iPS cells). (About DM1 and iPS cells). http://www.shanti-ctm.com/blog/2013/03/ips.html, accessed 20 October 2016.

Shim-bun, A. (1996) Yūseihogohō kaisei tachiba no sa. (Different perspectives on the revision of the Eugenic Protection Law). 14 February.

Sleeboom-Faulkner, M. (2008) Claiming the futures of human embryonic stem cell research in Japan: Minority voices and their amplifiers. Science as Culture 17(1): 85–97.

Sleeboom-Faulkner, M., Chekar, CK., Faulkner, A., Heitmeyer, C., Marouda, M., Rosemann, A., Chaisinthop, N., Chang, HC., Ely, A., Kato, M., Patra, PK., Su, YY., Sui, SS., Suzuki, W. and Zhang, XQ. (2016) Comparing national home-keeping and the regulation of translational stem cell applications: An international perspective. Social Science & Medicine 153: 240–249.

Song, P. (2010) Biotech pilgrims and the transnational quest for stem cell cures. Medical Anthropology 29 (4): 384–402.

Song, P. (2017) Biomedical Odysseys: Fetal Cell Experiments from Cyberspace to China. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sui, S. and Sleeboom-Faulkner, M. (2015) Governance of stem cell research and its clinical translation in China. EASTS 9: 1–16.

Tamai, M. and Kasuga, M. (2009) ‘Chūzetsu taiji riyō no shōgeki’ o megutte (Dialogue on the shocking news about the use of aborted foetus cells). In: M. Tamai and S. Hiratsuka (eds.) Suterareru inochi, riyō sareru inochi (Life Thrown away, Life Made Use of), Tokyo: Seikatsu-shoin, pp. 11–30.

The Japan Times. (2014) Keio team to begin clinical trial of new spinal injury treatment, 18 June. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/06/18/national/science-health/keio-team-begin-clinical-trial-new-spinal-injury-treatment/#.WAeDizufpAY, accessed 20 October 2016.

Titchkosky, T. and Michalko, R. (2012) The body as the problem of individuality: A phenomenological disability studies approach. In: D. Goodley, B. Hughes and L. Davis (eds.) Disability and Social Theory. New Developments and Directions. Basingstoke: Palgrave and MacMillan, pp. 127–142.

Tremain, S. (2005) Foucault, governmentality, and critical disability theory: An introduction. In: S. Tremain (ed.) Foucault and the Government of Disability. Chicago: University of Michigan Press, pp. 1–24.

Welfare and Medical Service Network System. (2016) Koremadeno kaigohokenseido no kaisei no keii to heisei 27 nendo kaigohōkenhōkaisei no gaiyō ni tsuite (History of laws for care and security, and a summary of the revised 2015 law), http://www.wam.go.jp/content/wamnet/pcpub/top/appContents/kaigo-seido-0904.html, accessed 20 October 2016.

Winance, M., Marcellini, A., and de Léséleuc, E. (2015) From repair to enhancement: The use of technical aids in the field of disability. In: S. Bateman, J. Gayon, S. Allouche, J. Goffette and M. Marzano (eds) Inquiry into Human Enhancement. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 119–137.

Yasuda, S. (2012). Shinkinkōsoku ga okottara (What to do when heart attack occurs). National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, http://www.ncvc.go.jp/cvdinfo/pamphlet/heart/pamph92.html, accessed 20 October 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The online version of this article is available Open Access.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kato, M., Sleeboom-Faulkner, M. Motivations for seeking experimental treatment in Japan. BioSocieties 13, 255–275 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-017-0067-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-017-0067-y