Abstract

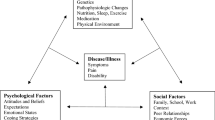

After briefly examining how expert authority has been constructed through an “associative” perspective, which privileges institutional relationships, I argue for the complimentary adoption of an “enactive” perspective, which centers on how experts demonstrate and earn authority with individual clients and communities. I synthesize scholarship revealing the uses of communication in expert–client relationships to argue that an enactive perspective allows for the study of how experts use “reiterative multivocality” to demonstrate to clients that they possess expert knowledge that is tailored to their interests, stakes, and values. Reiterative multivocality is the process of reaffirming, in different voices and formats, terms and symbols considered centrally important by other experts at the time. It allows experts to communicate authoritativeness through reiterating signs that reflect the collective’s efforts to maintain authority in response to shifts in client expectations. I focus on the case of expert authoritativeness in medicine, examining how it is constructed and maintained. The article argues that authority is not rooted solely in institutions but is developed and maintained by individual experts and clients, and that the language and processes used in the construction of authoritativeness is of central importance to sociologists. I expand upon the implications of both perspectives for method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At first blush, it may appear that the enactive perspective can be compared with the work of conversation analysts and ethnomethodologists interested in features of sequential ordering that comprise the interactions with those we refer to as experts (e.g., Maynard 1991). This is because the interactional processes that underpin authoritativeness described in the enactive perspective, like reiterative multivocality, also attend to careful parsing of episodes of talk and silence. However, those who take an enactive perspective toward authoritativeness are hesitant to reduce an understanding of episodes of authoritativeness to primarily reflect qualities of an “autonomous” sequence of interactional “turns.” This unwillingness to focus on the autonomous sequence originates not only in the empirical challenge presented by identifying those turns in venues where incipient experts, such as interrogated students in a law-school classroom, are learning their craft (Mertz 2007: 35–37). It also stems from the recognition that the enactive perspective captures features of culture often obscured by a focus on sequence, and attends to features of linguistic expression that, in Silverstein’s (1997: 632) terms, “appeal to multiple scopes of inclusiveness of what one might term ‘context.’” To be sure, in drawing attention to the enactive perspective my intention is not to revive perennial debates about scholars’ ability to capture context in studying interaction, because I recognize that any shared agreement towards defining an interaction’s context itself is likely unattainable (Duranti and Goodwin 1992: 2). Here, in synthesizing studies of authoritativeness in terms of an enactive perspective, I am merely reaffirming, with Hanks (2018: Chap 9), the importance of attending to a broader social backdrop in interpreting interactional dimensions of the scene at hand (see also Menchik 2019).

Relationships with peers are indeed important for maintaining authority. The collective is not an inert entity, but is rather the product of a group of people who set standards and develop norms, such as those that would lead doctors to call a peer a "quack." It is however outside of the scope of this paper to take up in detail the important issue of relationships to peers.

I do not mean to exclude communication and signification through, for instance, advertising or professional publication. But the focus of this article is on relationships with clients.

On the topic of clienthood, the enactive perspective offers a different way to understand variation in responsiveness to clients. Bourdieu (1991b) suggested that science and scholarship is a field in which practitioners are clients. The enactive perspective helps us to understand responsiveness to "clients" as a question of meaning, and not just institutional positioning or field autonomy. I thank a reviewer for pointing this out.

The apt description of experts’ “bringing into being” a client’s relational state is from Craciun (2016, p. 379).

The semiosis done by professionals likely cannot be reducible to the form discussed in the most common interpretation of Peirce’s (1955) index, which involves a physical trace and the memory of the person for whom it serves as a sign (107). Recognizing the differences in use and occasional controversy around the terms “index” and “indexical” in the sociology literature, in this paper I follow Rappaport’s (1999) reading of Peirce to conceptualize an index as “a sign which is caused by, or is part of, or, possibly, in the extreme case, is identical with, that which it signifies… they are perceptible aspects of events or conditions signifying the presence or existance of imperceptible aspects of the same events or conditions” (55). And so, “a rash indicates (is an index of) measles… the weathervane indicates the wind’s direction, the Rolls Royce indicates the wealth of its owner… the March on Washington of November 15, 1970 indicated the size and social composition of opposition to the war in Vietnam” (55).

Because it is indexical, some would argue that Foucault’s (1978, 1985) genealogical approach, one which would imply the relevance of work on expert authority along the lines of Larson (1984), is consistent with a semiotic one. But it is also the case that Foucault’s genealogical work is in fact rooted in the rejection of ideas that discourses are “authored” by humans, and a focus on what stands behind discursive forms (Carr 2011).

A vast range of post-WWII scientific production involves client-like stakeholders such as foundations, companies, or the state, a form of dependence with a long history (Baritz 1960; Biagioli 1994; Mukerji 2014). Sociologists have implicitly agreed that it is possible to compare these expert occupations; we’ve drawn upon and advanced theories developed in studies of scientists in research on medicine (e.g., Timmermans and Berg 2003), economics (Fourcade 2009), and finance (MacKenzie 2001).

Legal work has been a focus of enactive analyses since Riesman’s (1951) comparison between law and magic, in which he argued that non-lawyers assume you can know more about the law than is ultimately possible (125).

Panofsky (2018) shows how such “images of strength” can operate to bolster fields mired in controversy.

This emphasis on the relationship of rhetoric to expert authority makes the perspective compatible with the formulation of Friedrich (1958, p. 35), who argued that the communication of authority has a relationship to reason and reasoning, and need not be demonstrated through rational discourse, but rather possesses “the potentiality of reasoned elaboration – [those speaking] are ‘worthy of acceptance’.”

These examples suggest that in some communities it is likely that efforts at expert authoritativeness may benefit from the kind of disidentification processes engaged by more marginalized groups (c.f., Muñoz 1999).

Collins and Evans (2007) have identified an interactional expertise gained by some speakers who learn to answer and ask informed questions about a topic. However, questions remain about how convincingly the speech patterns they have learned to emulate will operate as indexes that reference multiple memberships that are pervasive in doctor talk (e.g., as teacher, scientist, lab colleague, member of an invisible college), a process Goffman referred to as footing (1979).

Such catchphrases serve as ethno-metapragmatic labels (Silverstein 2003), acting as a kind of shorthand caption for a particular emerging transformation in the occupation that broadcasts, in an aspirational and advertising way, its continued relevance in light of cross-occupation competition for business. The aspirational quality of these catchphrases makes them a likely means through which new institutional formations are propelled.

In one experiment, respondents shown images of a physician in a white coat were statistically significantly more willing to behave in multiple ways reflecting acceptance of physician authority, specifically to share their social, sexual, and psychological problems, to describe a strong intention to trust that doctor, to comply with their recommendations, and return for follow-up (Rehman et al. 2005).

References

Abbott, A. 1981. Status and Status Strain in the Professions. American Journal of Sociology 86: 816–835.

Abbott, A. 1988. The System of Professions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Agha, A. 2007. Language and Social Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baer, H.A. 1981. The Organizational Rejuvenation of Osteopathy: A Reflection of the Decline of Professional Dominance in Medicine. Social Science & Medicine 15 (5): 701–711.

Bail, C.A. 2016. Cultural Carrying Capacity: Organ Donation Advocacy, Discursive Framing, and Social Media Engagement. Social Science & Medicine 165: 280–288.

Balfe, M. 2016. Why Did U.S. Healthcare Professionals Become Involved in Torture During the War on Terror? Bioethical Inquiry 13 (3): 449–460.

Barker, K. 2009. The Fibromyalgia Story: Medical Authority and Women's Worlds of Pain. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Barthes, R. 1977. The Death of the Author. Image, Music, Text (trans: Heath, S.). (pp. 142–148). New York: Hill and Wang.

Bell, A. 1984. Language Style as Audience Design. Language in Society 13: 145–204.

Bellon, R. 2014. A Sincere and Teachable Heart: Self-denying Virtue in British Intellectual Life, 1736–1859. Leiden: Brill.

Berlant, J.L. 1975. Profession and Monopoly. Oakland: University of California Press.

Berliner, H.S. 1985. A System of Scientific Medicine. London: Tavistock Publications.

Biagioli, M. 1994. Galileo, Courtier. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blumhagen, D.W. 1979. The Doctor's White Coat: The Image of the Physician in Modern America. Annals of Internal Medicine. 91: 111–116.

Bourdieu, P. 1991a. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. 1991b. The Peculiar History of Scientific Reason. Sociological Forum 6: 3–26.

Breiger, R.L. 1974. The Duality of Persons and Groups. Social Forces 53 (2): 181–190.

Briggs, C.L. 2003. Stories in the Time of Cholera. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bosk, C. L. 1979 [2003]. Forgive and Remember. Managing Medical Failure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Callon, M., and V. Rabeharisoa. 2008. The Growing Engagement of Emergent Concerned Groups in Political and Economic Life: Lessons from the French Association of Neuromuscular Disease Patients. Science, Technology, & Human Values 33 (2): 230–261.

Carr, E.S. 2010. Enactments of Expertise. Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 17–32.

Carr, E.S. 2011. Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clemens, E.S. 1986. Of Asteroids and Dinosaurs: The Role of the Press in the Shaping of Scientific Debate. Social Studies of Science. 16 (3): 421–456.

Cohen, A.C., and S.M. Dromi. 2018. Advertising Morality: Maintaining Moral Worth in a Stigmatized Profession. Theory and Society. 47: 175–206.

Collins, H., and R. Evans. 2007. Rethinking Expertise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Conley, J.M., and W.M. O'Barr. 2005. Just Words: Law, Language, and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Craciun, M. 2016. The Cultural Work of Office Charisma: Maintaining Professional Power in Psychotherapy. Theory and Society 45 (4): 361–383.

Davie, G. 2015. Poverty Knowledge in South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Domhoff, W. G. 1967 [2006]. Who Rules America? Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Duranti, A., and C. Goodwin (Eds.) 1992. Rethinking Context: Language as an Interactive Phenomenon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erikson, E., and J. Parent. 2007. Central Authority and Order. Sociological Theory 25 (3): 245–267.

Evans, J.A., and P. Aceves. 2016. Machine Translation: Mining Text for Social Theory. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 21–50.

Eyal, G. 2013. For a Sociology of Expertise: The Social Origins of the Autism Epidemic. American Journal of Sociology 118: 863–907.

Eyal, G., and G. Pok. 2015. What is security expertise? From the sociology of professions to the analysis of networks of expertise. In Capturing Security Expertise, ed. T. Berling and C. Bueger. London: Routledge.

Foucault, M. 1978. The History of Sexuality, Volume I. New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. 1985. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality, Volume II. New York: Vintage.

Fourcade, Marion. 2009. Economists and Societies: Discipline and Profession in the United States, Britain, & France, 1890s to 1990s. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Friedrich, C.J. 1958. Authority. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Freidson, E. 1968. The Impurity of Professional Authority. In Institutional Office and the Person, ed. H.S. Becker et al. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

Freidson, E. 1970. Profession of Medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gal, S., and J. Irvine. 2019. Signs of Difference: Language and Ideology in Social Life. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Ginzburg, C., and A. Davin. 1980. Morelli, Freud and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method. History Workshop 9: 5–36.

Goffman, E. 1979. Footing. Semiotica 25 (1/2): 1–30.

Hanks, W. F. 2018. Language and Communicative Practices. Routledge.

Hasty, J.D. 2015. Well, He May Could Have Sounded Nicer: Perceptions of the Double Modal in Doctor-Patient Interactions. American Speech 90 (3): 347–368.

Hymes, D. 1972. On Communicative Competence. In Sociolinguistics, ed. J. Pride and J. Holmes, 269–293. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Iser, W. 1978. A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Johnson, T.J. 1972. Professions and Power. London: MacMillan.

Kempner, J. 2014. Not Tonight: Migraine and the Politics of Gender and Health. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kiesling, S.F. 2001. ‘Now I Gotta Watch What I Say’: Shifting Constructions of Masculinity in Discourse. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11 (2): 250–273.

Konrád, G., and I. Szelenyi. 1979. The Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power. San Diego: Harcourt.

Krause, E.A. 1996. Death of the Guilds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Larson, M.S. 1984. The Production of Expertise and the Constitution of Expert Power. In The Authority of Experts, ed. T. Haskell, 28–80. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Light, D.W. 2000. The Medical Profession and Organizational Change: From Professional Dominance to Countervailing Power. In The Handbook of Medical Sociology, ed. C. Bird, P. Conrad, and A. Fremont, 201–216. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Liu, S. 2006. Client Influence and the Contingency of Professionalism: The Work of Elite Corporate Lawyers in China. Law & Society Review 40 (4): 751–782.

Liu, K., M. King, and P.S. Bearman. 2010. Social Influence and the Autism Epidemic. American Journal of Sociology 115 (5): 1387–1434.

MacKenzie, D. 2001. Physics and Finance: S-terms and Modern Finance as a Topic for Science Studies. Science, Technology, & Human Values 26 (2): 115–144.

Masco, J. 2010. Bad Weather: On Planetary Crisis. Social Studies of Science. 40 (1): 7–40.

Maynard, D.W. 1991. Interaction and Asymmetry in Clinical Discourse. American Journal of Sociology 97: 448–495.

McDonnell, T.E., C.A. Bail, and I. Tavory. 2017. A Theory of Resonance. Sociological Theory 35 (1): 1–14.

McGrath, B.P. 1996. Is White-Coat Hypertension Innocent? The Lancet 348: 630.

McLean, P.D. 2007. The Art of the Network. Durham: Duke University Press.

Menchik, D. 2014. Decisions About Knowledge in Medical Practice: The Effect of Temporal Features of a Task. American Journal of Sociology 120: 701–749.

Menchik, D. 2017. Interdependent Career Types and Divergent Standpoints on the Use of Advanced Technology in Medicine. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 58: 488–502.

Menchik, D. 2019. Tethered Venues: Discerning Distant Influences on a Fieldsite. Sociological Methods and Research 48: 850–876.

Menon, A.V. 2017. Do Online Reviews Diminish Physician Authority? The Case of Cosmetic Surgery in the US. Social Science & Medicine 181: 1–8.

Mertz, E. 2007. The Language of Law School. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Milroy, J., and L. Milroy. 1985. Linguistic Change, Social Network and Speaker Innovation. Journal of Linguistics 21 (2): 339–384.

Mukerji, C. 2014. A Fragile Power: Scientists and the State. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Muñoz, J.E. 1999. Disidentifications. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Navarro, V. 1986. Crisis, Health, and Medicine: A Social Critique. London: Tavistock Press.

Navon, D. 2017. Truth in Advertising: Rationalizing ads and knowing consumers in the early twentieth-century United States. Theory and Society 46 (2): 143–176.

Panofsky, A. 2018. Rethinking scientific authority: Behavior genetics and race controversies. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 6 (2): 322–358.

Parsons, T. 1951. The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

Padgett, J.F., and C.K. Ansell. 1993. Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400–1434. American Journal of Sociology 98 (6): 1259–1319.

Peirce, C.S. 1955. Philosophical Writings of Peirce. New York: Dover. Publications.

Pescosolido, B.A., and J.K. Martin. 2004. Cultural Authority and the Sovereignty of American Medicine: The Role of Networks, Class, and Community. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 29 (4): 735–756.

Phillips, D. 1998. Black Minority Ethnic Concentration, Segregation and Disperal in Britain. Urban Studies 35 (10): 1681–1702.

Podesva, R.J. 2011. Salience and the Social Meaning of Declarative Contours: Three Case Studies of Gay Professionals. Journal of English Linguistics 39 (3): 233–264.

Prentice, R. 2012. Bodies in Formation: An Ethnography of Anatomy and Surgery Education. Durham: Duke University Press.

Quadagno, J.S. 2004. Physician Sovereignty and the Purchasers’ Revolt. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 29 (4): 815–834.

Rappaport, R. 1999. Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reed, I.A. 2016. Between Structural Breakdown and Crisis Action: Interpretation in the Whiskey Rebellion and the Salem Witch Trials. Critical Historical Studies 3 (1): 27–64.

Rehman, S.U., et al. 2005. What to Wear Today? Effect of Doctor’s Attire on the Trust and Confidence of Patients. The American Journal of Medicine 118 (11): 1279–1286.

Riesman, D. 1951. The Lonely Crowd. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rudwick, M.J.S. 1985. The Great Devonian Controversy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sarat, A., and W. Felstiner. 1998. Divorce Lawyers and their Clients: Power and Meaning in the Legal Process. London: Oxford University Press.

Schudson, M. 2011. The Sociology of News. New York: WW Norton.

Shapin, S. 1988. The House of Experiment in Seventeenth-Century England. Isis 79 (3): 373–404.

Silverstein, M. 1997. Commentary: Achieving Adequacy and Commitment in Pragmatics. Pragmatics, 7 (4): 625–633.

Silverstein, M. 2003. Indexical Order and the Dialectics of Sociolinguistic Life. Language & Communication 23 (3): 193–229.

Silverstein, M. 2016. Semiotic Vinification and the Scaling of Taste. In Scale, ed. E. Carr and M. Lempert, 185–212. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stampnitzky, L. 2013. Disciplining terror: How experts invented “terrorism”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Starr, P. 1982. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books.

Thomas, W.I., and F. Znaniecki. 1918. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tian, X. 2014. Rumor and Secret Space Organ-Snatching Tales and Medical Missions in Nineteenth-Century China. Modern China 41 (2): 197–236.

Timmermans, S. 2005. Death Brokering: Constructing Culturally Appropriate Deaths. Sociology of Health & Illness 27 (7): 993–1013.

Timmermans, S., and M. Berg. 2003. The Gold Standard: The Challenge of Evidence-Based Medicine and Standardization in Health Care. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Traweek, S. 1992. Beamtimes and Lifetimes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Traweek, S. 2009. Beamtimes and Lifetimes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Treakle, A.M., et al. 2009. Bacterial Contamination of Health Care Workers' White Coats. American Journal of Infection Control 37 (2): 101–105.

Viechnicki, G., and J. Kuipers. 2006. “It’s all Human Error!”: When a School Science Experiment Fails. Linguistics and Education 17 (2):107–130.

Vinson, A.H. 2016. ‘Constrained Collaboration’: Patient Empowerment Discourse as Resource for Countervailing Power. Sociology of Health & Illness 38 (8): 1364–1378.

Waitzkin, H. 1979. A Marxian Interpretation of the Growth and Development of Coronary Care Technology. American Journal of Public Health 69: 1260–1268.

Waller, W. 1932. The Sociology of Teaching. Hoboken: Wiley.

Warner, J.H. 1992. The Fall and Rise of Professional Mystery: Epistemology, Authority, and the Emergence of Laboratory Medicine in Nineteenth-Century America. In The Laboratory Revolution in Medicine, ed. A. Cunningham and P. Williams, 110–141. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whooley, O. 2014. Knowledge in the Time of Cholera: The Struggle over American Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilkins, E. M. 1983 [1958]. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Acknowledgements

For comments on the ideas presented here, I am grateful to Larry Busch, Kevin Elliott, Susan Gal, Laura Hirshfield, Dan Hirschman, Tania Jenkins, Joe Martin, Kelly Underman, Alexandra Vinson, Owen Whooley, and Suzanne Evans Wagner. This essay is dedicated to Michael Silverstein, for his support and inspiration as I developed many of these ideas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menchik, D.A. Authority beyond institutions: the expert’s multivocal process of gaining and sustaining authoritativeness. Am J Cult Sociol 9, 490–517 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00100-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00100-3