Abstract

Bangladesh has made progress in advancing adolescent girls’ education, but there remain substantial evidence gaps around age and gender differences in motivations, retention, and access to education for adolescents living in urban slums. This article draws on quantitative and qualitative data collected in 2017 and 2018 by Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) with adolescents aged 10–17 across three low-income areas in Dhaka to explore adolescent educational attainment, aspirations, and environmental factors that constrain both. We find high educational and professional aspirations among adolescents and their parents, with parental support being an important predictor of both current enrolment and adolescent aspirations. Location is also an important predictor of adolescent aspirations and enrolment, highlighting the importance of infrastructure and services, integration into the city, and stability of the community (including schools and facilities), along with higher incomes and better employment opportunities for households.

Resume

Il est essentiel d’accroître l'accès à l'éducation et d’améliorer les résultats scolaires pour faire en sorte qu'aucun·e adolescent·e ne soit laissé·e pour compte. Le Bangladesh a fait des progrès dans la promotion de l'éducation des adolescent·es. Cependant, il reste des questions quant aux motivations des adolescentes, aux taux de retention et d’abandon, ainsi qu’au passage vers l'enseignement secondaire et au-delà. Il existe notamment des lacunes dans les données sur les différences d'âge et de sexe dans les bidonvilles urbains. Le programme de recherche Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (Genre et Adolescence: des données probantes mondiales ou GAGE) a collecté des données autour de Dhaka (2017–2018) par le biais de méthodes mixtes, auprès d'adolescent·es âgé·es de 10 à 17 ans. Le programme a constaté que les aspirations éducatives des adolescent·es et de leurs parents sont élevées, en particulier pour les filles, et que l'éducation est considérée comme une voie légitime vers une vie meilleure. Cependant, ces aspirations peuvent échouer car les filles et les enfants les plus pauvres sont affecté·es de manière disproportionnée par divers obstacles socio-économiques et structurels. Il existe un manque de systèmes pour aider les adolescent·es qui travaillent et marié·es à poursuivre leurs études, afin qu'aucun·e adolescent·e ne soit laissé·e pour compte.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents living in urban slums in the world’s megacities are particularly vulnerable to dropping out of school compared with urban adolescents living outside of slums—due to higher rates of poverty and child labour. Girls living in such environments are twice as likely to be married before the age of 18 as those in better-off households (Greene et al. 2015; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) 2012), with parents as principal decision-makers, which further contributes to reduced enrolment rates for girls (Raj et al. 2014). While there is extensive research on adolescents in rural settings, we know less about the challenges facing adolescents in urban settings and the opportunities available to them (Bradshaw et al. 2017). With growing urbanisation and subsequent diversification of urban spaces into informal settlements and slums, understanding these contexts and inequalities becomes urgent if we are to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) pledge to leave no one behind. Education is a powerful instrument for reducing inequality by contributing to higher incomes and enabling individuals to improve their quality of life and broaden their options (Khan and Williams 2006).

Bangladesh’s capital city, Dhaka, is thought to have the largest slum population and highest proportion of slum dwellers of any other large city (Bangladesh Planning Commission 2015, p. 102). Residents in these areas have low levels of education; jobs are scarce and precarious, and structural violence and pervasive crime further heighten personal and social insecurity (Banks 2012; Rashid 2006; Wood 1998). Moreover, 28% of the city’s population are under 14 years of age, making adolescents a large share of Dhaka’s rapidly growing population (National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), 2014). Understanding the impact of poverty on the development and, especially, educational attainment of adolescents in urban slums is therefore critical to improving the future trajectory of the country’s development.

This paper uses mixed-methods data collected in 2017 and 2018 as part of the Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence (GAGE) programme with adolescents (aged 10–12 and 15–17) living in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh, to explore their aspirations and attainment, and the barriers to both. We find that aspirations for continued education—among adolescents and their caregivers—are high (95% of adolescents in our sample aspired to complete secondary school), but only 75% were enrolled in school, indicating barriers to realising those aspirations. We find that location factors––such as infrastructure and services, integration into the city, and stability of the community (including schools and facilities)––along with higher incomes and better employment opportunities for households have important implications for adolescents in relation to paid work and early marriage. These are also important factors in determining educational aspirations. Our findings contribute important evidence in support of the ‘leave no one behind’ agenda and its focus on transforming systems in conjunction with efforts to alleviate poverty.

As well as contributing to the scant literature on the challenges facing adolescents in highly urbanised contexts, this article contributes to the evidence on the gendered nature of educational outcomes and the particular vulnerabilities of adolescents who are most at risk—such as those at risk of early marriage or child labour. Bangladesh has the lowest proportion of children in secondary school in South Asia, with an enrolment rate of 50% compared to 70% in neighbouring India (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2020). Increased dropout rates among girls are due to parental fears of sexual harassment of their daughters, which often drives early marriage. A survey by ActionAid found that 69% of girls reported being harassed on the way to school (Karim 2007), while UNICEF (2020) reports that Bangladesh has the fourth highest rate of child marriage globally. More generally, dropout (whether from primary or secondary school) is driven by vulnerabilities such as poverty, gender discrimination, disability status, ethnic background, and living in areas that are hard to reach (Sarker et al. 2019).

While there is a great deal of evidence about girls’ educational outcomes, there is less evidence on boys’ outcomes, and, over time, less attention has been given ‘to disentangling the factors and processes that lead to different outcomes’ (Presler-Marshall and Stavropoulou 2017, p. 4). Moreover, most research is quantitative, precluding it from unpacking the context that would enable better programming (ibid.). The mixed-methods nature of the GAGE data, as well as the programme’s focus on understanding gender and age differences, allows us to address both those gaps, particularly in relation to insights into adolescents’ educational and professional aspirations. We also provide insights into the role of community (including infrastructure and wealth) in educational trajectories by including adolescents living in three different low-income urban contexts that vary in terms of the duration and stability of the community, as well as in access to health and education services.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. “Conceptual Framework and Background” section gives the context of Bangladesh’s progress on education and elaborates on the GAGE conceptual framework. “Data and Methods” section presents the study locations, sample, research data, and methods. “Results” section presents the main results from quantitative and qualitative analysis around our three themes: educational and professional aspirations; continuing education; and school and community infrastructure. “Implications for Policy and Practice” concludes by setting out the implications of our findings for policy and practice.

Conceptual Framework and Background

Conceptual Framework

Our analysis is situated within the GAGE conceptual framework (GAGE consortium 2019), which focuses on adolescents’ multidimensional capabilities in six key domains: education and learning; health, nutrition, and sexual and reproductive health; bodily integrity and freedom from violence; psychosocial wellbeing; voice and agency; and economic empowerment. The framework also emphasises the interconnectedness of the ‘3 Cs’––capabilities, change strategies, and contexts––in order to understand what works to support adolescents’ development and empowerment. The conceptual framework is useful for analysing educational outcomes situated at the family, community and global levels, which must be considered in efforts to deliver transformative change.

The concept of aspirations is closely related to the capability approach upon which the GAGE conceptual framework is built, although it has also been used in the literature more narrowly with educational and career-related achievements. Hart (2016) shows how aspirations are converted to capabilities and functioning, analyses the processes through which this happens, and shows how certain capabilities become functioning, defining them as being ‘relational, (…) dynamic, often connected to other aspirations held by the individual as well as by others… [and being] institutional, political, legal and shared by family members’ (ibid, p. 326). However Hart emphasises that the freedom to aspire has then to be transformed into capabilities, where the judgements of people around the adolescent, regarding the feasibility of aspirations play a role in determining how those aspirations are transformed into actions. Likewise, Appadurai (2004, p. 67) has argued that ‘aspirations are never simply individual. They are formed in interaction and in the thick of life’. Both conceptualisations align with GAGE’s conceptual framework.

Educational aspirations have been found to be strongly correlated with poverty, in that low-income households often have lower aspirations due to resource constraints; they are also linked to growth in inequality due to the role they play in determining whether and where an individual invests effort into realising a goal (Dalton et al. 2016; Genicot and Ray 2017). If we take aspirations to be a reflection of parents’ and children’s values, in line with other studies (Kingdon 2005), recent analysis has found that there are profound inequalities between children from different social groups, and also between children within households (Dercon and Singh 2011). In higher-income contexts, both adolescent and parental aspirations have been found to be positively related to achievement and educational attainment (Gorard et al. 2012; Khattab 2014). However, evidence from lower-income contexts is thin, highlighting the need for more research in low-income settings.

Context

In the past decade, Bangladesh has made significant progress in increasing educational attainment. The literacy rate (for those aged 15+) has increased from 58.8% in 2011 to 73.9% in 2018, evidencing the country’s progress toward the goal of Education for All by 2021. Disaggregated by gender, the literacy rate rose from 62.5 to 76.7% (males) and from 55.1 to 71.2% (females) (World Bank Development Indicators 2020).

In Bangladesh, education is seen as a pathway to achieving a better life, and educational aspirations––among adolescents and their parents––are high. Moreover, there is evidence of increasing aspirations across generations; for example, women who married as adolescents want their children to pursue an education and get a job (Kabeer et al. 2011). This desire for education as a route to employment is part of a broader trend: in the past 10–15 years, educational aspirations for girls (their own aspirations and their parents’) have increased alongside an increase in employment opportunities in the garment sector, which has in turn increased the economic value of education (CARE 2016; Heath and Mobarak 2012; Heissler 2011). However, Heissler also points out that formal schooling has not always delivered chakri by which are meant more secure and better-paid jobs with status.

Increases in educational aspirations for girls have also occurred independently of improved employment opportunities. Del Franco (2010) finds that the shift toward adolescents remaining enrolled through secondary school creates spaces for young women to reflect on their self-perception and develop personal expectations and aspirations separate from the dominant social norms. In other contexts, girls’ education is perceived more in terms of better marriage prospects rather than school performance or job aspirations, highlighting both poor quality of schooling and rigid gender segregation within labour markets (Mahmud and Amin 2006).

This article focuses on two important constraints that are especially relevant for adolescents living in urban slums: paid work and early marriage. Research has found that children who work and attend school fall behind their peers in term of age progression; the more hours the child works, the more they fall behind (ILO and UNICEF 2021). Likewise, early marriage is significantly negatively associated with educational attainment. Girls with no education are nearly four times more likely to be married early compared to those who have completed secondary education or higher, and girls with primary but incomplete secondary education are three times more likely to be married early compared to those with secondary education or higher (Biswas et al. 2019).

Although education reforms in Bangladesh represent an important step toward improving access and outcomes, certain factors––inequality and social exclusion (due to lack of access to quality schools), systems of assessment, and discipline (including corporal punishment)––prevent education from being transformative for young adolescents living in poverty (Cameron 2010). Differences in attainment are aggravated by social and economic inequalities, as various studies have demonstrated (Asadullah et al. 2019; Hossain and Hickey 2019).

Data and Methods

This article draws on quantitative and qualitative data collected by GAGE in 2017 and 2018 across three low-income study sites in Dhaka. These locations were chosen to capture variation in the duration and stability of the community, access to health and education services, and integration into Dhaka.

Study Locations

Community A is a large settlement of 8,400 households (37,000 people) peripheral to Dhaka city. This slum is located in the newly urbanised area near the industrial area of Tongi, on land leased from the government, and is reported by its residents as being secure. Compared to the two other communities (see below), access to health and education services is much better: there is a government secondary school, 14 private schools, and a 300-bed hospital nearby. In community A, adolescents mainly work in the garments factories, or selling vegetables or fish. Poorer adolescent boys pull rickshaws. Older and more educated adolescent girls work in show rooms (frequented by well-off households) and tutorial centres for students.

Community B is a small, private slum, with 300 households in compounds, located in central Dhaka. There is a high level of migration and limited access to services, and no other NGO or healthcare facilities apart from a women’s health facility (run by an international NGO) and a hospital 3 km away. The area has electricity but no access to gas, after illegal gas lines were disconnected. Roads and alleyways are uneven and of poor quality. Child labour is prevalent, indicating higher levels of poverty, with female study respondents reporting that younger and older adolescent boys work as labourers in grocery shops or with truck owners to load and unload bricks and sand. Younger boys are tempo (‘tuk tuk’) helpers; some work in factories such as tanneries and some even do hazardous occupations such as welding. Community B is separated from the city and facilities such as hospitals by a main road, which is difficult to cross.

Community C, with approximately 3000 households, is situated in central Dhaka and has fairly good roads constructed by an international NGO. This slum was originally a rehabilitation camp for people who had lost their homes and livelihoods due to river erosion; it is built on government-leased land. It has three NGO schools and one government school. There are several service delivery organisations active in the slum. Adolescent boys in community C mentioned that both boys and girls from poorer households work in the printing and garments factories. Overall, adolescents reported having access to services, such as vaccinations and other free health services, from a government urban health project. Most residents claimed to have legal electricity and gas connections, although people living in the inner area, which is much poorer, relied on illegal connections and paid much more than others for access.

Data Collection

Data collection took place during December 2017 and January 2018 and entailed quantitative interviews with 780 adolescent girls and boys and qualitative interviews with a subsample of 36 adolescent girls and boys, aged 10–12 and 15–17. To identify potential respondents, a household listing was conducted in all three locations in November and early December 2017.Footnote 1 Households with at least one adolescent aged 10–12 or 15–17 were randomly selected to participate in the study to ensure representativeness of the sample. If the household had more than one eligible adolescent, a single adolescent was randomly selected for the survey.Footnote 2 The qualitative research sample was drawn from the quantitative sample using a stratified random approach.Footnote 3

Quantitative surveys were conducted with the adolescent and their primary female caregiver. The survey included questions about the adolescent’s life across all six GAGE capability domains, including adolescent and caregiver aspirations around education and professional careers, educational attainment, paid work, and early marriage (Baird et al. 2019a, b). Quantitative data was also collected from schools that serve adolescents in the three slums, focusing on infrastructure, programming, and amenities (Baird et al. 2019c).

Separate ethical reviews were carried out for both the qualitative and quantitative study components. For the adolescent respondents, we obtained both the consent for their guardians and their assent before carrying out the survey and the in-depth interviews.

Qualitative and Participatory Research Methods

In-depth qualitative and participatory research was conducted with a subset of adolescents, their parents and siblings. A qualitative toolkit was designed to mirror the ‘3 Cs’ GAGE conceptual framework (see also Jones et al. 2018, 2019). GAGE adapted one tool, A Few of My Favourite Things (originally used in longitudinal qualitative research with UK adolescents) (Thomson et al. 2011; Thomson and Hadfield 2014), to explore adolescent capabilities. Interviewers probed the significance of an object chosen by the adolescent in his or her life and how it related to the six capability domains. The toolkit included a number of group-based exercises such as a community timeline and a tool on social norms that was used in focus group discussions (FGDs) with adults to elicit information on significant changes in the community and normative beliefs on issues such as education and marriage. These adult-focused discussions were complemented by community mapping with adolescents to reveal their access to and familiarity with various community spaces. Researchers also conducted key informant interviews with government officials and civil society representatives at community, district, and regional levels.

Quantitative Measures

To measure educational aspirations, we asked adolescents to identify the highest level of schooling they would like to attain assuming no constraints, and classify aspirations into two categories: (1) aspire to less than post-secondary education; and (2) aspire to at least some university education.Footnote 4 Educational outcomes are school enrolment status and highest grade attained, measured in years of schooling, including the grade of current enrolment.

We explore a number of dimensions that affect school enrolment and aspirations of adolescents, including their own employment aspirations, parental support, engaging in paid work, experiencing early marriage, household poverty, and community infrastructure. We asked adolescents what career they would choose and to classify responses into ‘skilled labour’, ‘unskilled labour’, ‘agricultural work’, ‘professional work’, ‘retail work’, ‘unpaid work’, or ‘other’. In this article we focus on adolescent aspirations for professional careers––the category requiring the highest levels of education. We measure parental support through caregiver aspirations for the adolescent’s educational attainment: a binary indicator that the caregiver aspires the adolescent to attain at least some university education. Household poverty is measured with a binary indicator for the literacy of the household head and an asset wealth index constructed using principal component analysis (PCA) following Filmer and Pritchett (2001). We control for community infrastructure with community fixed effects. In addition to these measures, we provide more context on the experiences of adolescents in our sample through descriptive statistics on school infrastructure in the three study locations, and the reasons for dropping out of school among key subgroups.

Quantitative Analysis Methods

This article utilises descriptive statistics to describe the environment and experiences of adolescents in relation to education, and regression analysis to explore the association between adolescent aspirations and school attainment and environmental factors. For the regression analysis, we use ordinary least squares (OLS) for both continuous and binary outcomes. In all models, in addition to environmental factors, we include binary indicators for gender (female compared to male), age cohort (younger, 10–12 years, compared to older, 15–17 years), and location (community A, B, or C) to explore how varying degrees of vulnerability manifest in adolescents’ experiences. We also control for whether the adolescent has any physical disabilities, the adolescent’s normalised score on a Raven’s cognitive test to control for innate ability (Strauss et al. 2016),Footnote 5 and use an indicator for being a household with multiple adolescents, for sampling design considerations. All means and models utilise sample weights to make results representative of the study locations, and standard errors are clustered at the community level. All quantitative analysis is complemented by qualitative data on the same areas of enquiry.

Results

The State of Educational Aspirations and Enrolment

You see, we have got admitted to school. We may have our wishes. But our wishes are never meant to be fulfilled, no? It’s because we can’t fulfil our wishes ourselves; if God is not willing, how can we fulfil our wishes? I don’t have any wishes. However, if God is willing, I will continue my studies so I can be a pilot someday. (11-year-old girl, community B)

Most adolescents see education as a pathway to achieving a better life, which suggests that they have internalised government messaging (since the 1990s) that education leads to better livelihood opportunities. In qualitative interviews, many adolescents mentioned dreams of having a high-status and well-paid job, such as a teacher, or at least getting a university degree, which many believed would lead to those opportunities. Others wanted to at least complete their Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) exam, which would allow for some entry-level jobs (such as shop assistant), as many realise that they will not be able to continue education beyond secondary school level because of their family’s economic status.

Table 1 corroborates qualitative accounts of high education and professional aspirations. It shows that 95% of adolescents aspire to complete at least some secondary school, 62% of in-school adolescents aspire to attain at least some university education, and 72% of adolescents aspire to a professional career. Interestingly, girls have higher aspirations than boys for university education (57% vs 49%) and for attaining a professional career (85% vs 59%).

However, despite high aspirations for secondary education, only 75% of all adolescents in the sample were currently enrolled in school, and only 55% of the older cohort. Looking to variation in aspirations and enrolment rates by location points to one explanation for the gap between aspirations and reality. Although aspirations for secondary education are relatively similar across locations (varying from 89% in community B to 99% in community A), they vary widely when it comes to enrolment rates, from as low as 55% in community B to 85% in community A—aligning with the relative wealth and stability of community A compared to community B. Indeed, on average, adolescents in community B have attended just under five years of schooling, indicating that the transition from primary to secondary school is the time when many drop out. Aspirations for university education appear to be more closely correlated with community stability.

Community B is the poorest of the three study locations. Despite being located centrally, residents are not connected to the services and facilities of Dhaka, and employment opportunities for adults and adolescents are limited. The community has a high proportion of recent migrants, and is the least stable i.e. its status is the most precarious in terms of security of tenure of the three sites studied. Housing conditions were poor and community-level interviews highlighted that drug abuse was common among both adolescents and adults. The GAGE school survey found that there were no government-run schools in the area and, of the seven non-government schools that were there, none had computers, only 14% had girls’ clubs, 28% had co-ed clubs, and 43% had programmes on sexual and reproductive health (SRH), and none had special needs programming. In contrast, community A has 15 schools, one of which is government-run; 13% of those schools have computers, 13% have SRH programming, and 13% have special needs programming, although there are no clubs. Though enrolment is lower in community C than in community A, the former is relatively well-developed and stable, with many schools; 60% report having computers, 20% have girls’ clubs, 20% have co-ed clubs, 60% have SRH programming, and 20% have special needs programming.

Table 2 provides summary statistics for the most common reasons for dropping out of school. Poverty is the most common reason, with over 40% of adolescents reporting a reason directly related to poverty (such as school fees and supplies being too expensive, travel being unsafe or too expensive, engaging in paid work, lack of food, or early marriage). Poverty appears to be the largest barrier for older girls: 29% reported dropping out of school because of school fees and supplies being too expensive, and 9% dropped out due to early marriage. Qualitative interviews highlight the role of poverty in educational attainment despite aspirations to continue schooling. A 16-year-old girl from community B stated: ‘My mother told me that she would continue supporting my studies till she has the last drop of blood in her veins. But we are poor. I don’t know if I would be able to continue my studies. But both my mother and I have the same wish regarding continuing my studies.’

Nearly a third (30%) of adolescents reported dropping out because of lack of interest, and this was particularly common among the younger male cohort (45%). The qualitative interviews heard reports of unsatisfactory school experiences among younger boys who felt that they received less attention and support from teachers and parents than did girls. Attendance of boys at secondary school was also lower than that of girls. Both these factors––low attendance and dropping out for lack of interest––may be explained by the poor quality of education, with teachers not being able to retain adolescent boys’ interest. Qualitative data also shows that girls are more focused on going to school and studying harder. It could be that given their limited mobility compared to boys, girls have fewer distractions and more time to concentrate on studying. Also they may want to avoid getting married early. The qualitative observations and interviews with boys and their parents highlighted that adolescent boys have greater freedom, which can distract them from studying; parents also have less control over how boys spend their time, given the increasing extra-curricular activities taking place in the slums and in the city (such as joining gangs, hanging out in youth clubs or internet cafes, and playing soccer or cricket).

Surprisingly, although bullying and corporal punishment were mentioned in the qualitative interviews as a disincentive for continuing school, only 2% of adolescents (and 8% of younger boys) reported this as a reason for dropping out. This may be due to corporal punishment being so widespread that it has become normalised—82% of adolescents reported experiencing corporal punishment and 76% reported being physically abused by a teacher.

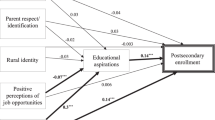

Drivers of Educational Aspirations and Attainment

We now turn to regression results to understand the importance of environmental factors in influencing aspirations and educational attainment. Table 3 presents estimation results for educational aspirations in columns 1 and 2, and for educational attainment in columns 3 and 4. Columns 1 and 3 present estimates over the whole sample of adolescents, while columns 2 and 4 present estimates for the younger cohort only, which allows us to explore the role of parental aspirations in shaping adolescent aspirations and attainment.

Adolescent Aspirations

Both quantitative and qualitative data also suggests that adolescents understand that more education is needed for professional careers, as those who aspire for professional careers are 14.7% points more likely to aspire to university education among the younger cohort (p < 0.10, column 2) and are 15.4% points more likely to be currently enrolled in the whole sample (p < 0.05, column 3). Moreover, adolescents who aspire to at least some university education are 12% points more likely to be enrolled in school (p < 0.05, column 3), aligning with other literature on the positive relationship between aspirations and educational attainment.

Qualitative interviews provide more context. A 12-year-old girl from community C was adamant about enrolling in one of the best schools in the area, perceiving that this would lead to better occupations and opportunities: ‘I want to study in a very good college… But my father wants me to study in the colleges nearby. I really want to be a doctor. If I can’t study there, then I am finished!’ Moreover, adolescents who are currently enrolled in school have consistently higher aspirations for education and professional careers, indicating that they adjust their expectations according to their realities. But some adolescents remained fearful as to whether their aspirations were realistic, given their socioeconomic status, as a 16-year-old girl from community B noted: ‘I want to be a teacher. But do dreams ever come true for a poor man’s daughter?’.

Parental Aspirations and Role Models

Adolescents with female caregivers who aspire for them to attain some university education are 33% points more likely to aspire to the same (p < 0.01, column 2) and are 6.9% points more likely to be currently enrolled in school (p < 0.05, column 4).

Female caregiver aspirations for their children are high, with 97% of primary female caregivers aspiring for the adolescent to attain at least some secondary education and 44% aspiring for at least some university education. In qualitative interviews, parents from all three locations shared that compared to their own parents, they are far more supportive of their children going to school and try to meet their children’s educational needs. They also reported regretting that they had not prioritised education when they were young, and some regretted not having completed primary education: ‘I have made many mistakes. I would not allow them to do the same. I would support [them] to continue their study’ (father of adolescent in community A).

Parental aspirations for their adolescents mostly centred on enabling their child to have a better future––better than the one they had. As the mother of an adolescent girl in community C said: ‘My future? My dream is now very big. My dream is to educate my children, get them jobs. Then they will earn. I will complete all of this and then get them married. This is my dream now.’

This was echoed in her daughter’s aspirations: ‘I want to stand on my own feet… How? Well I want to study. The more I study, the more it will increase my interest. And it will create better opportunities for me to stand on my own feet. After all, education is the key to the future.’

Adolescent girls and their parents also recognise the value of education in opening up different trajectories, as a means to greater independence, finding better employment, and improving their position in negotiating their rights after marriage.

The father of a girl in community C explained that education would enable his daughter to avoid being completely dependent financially on her (future) spouse: ‘If my girl passes an honours degree or master’s, then if the husband is not quite right, she will be able to live by teaching, by giving private tuition. She will stand on her own feet. So, the future will be better.’

Younger adolescents with a role model outside the household are 14.6% points more likely to aspire to some university education (Table 3, column 2). In qualitative interviews, both boys and girls mentioned that their aspirations were influenced by people they considered role models. These included parents, teachers and, in some cases, celebrities. Some girls mentioned female teachers as role models (aligning with their aspirations for a professional career), explaining that they admired them because they are educated and empowered. For example, a 12-year-old girl in community C mentioned that her private tutor is very vocal and confident: ‘She talks very nicely. She can explain things well. If she sees anything wrong happening, she can protest.’

Paid Work

Table 3, column 3, shows that adolescents who are engaged in paid work are 42% points less likely to be enrolled in school. While this association holds both for boys and girls, it is most common for boys. In unreported results, boys who engage in paid work are 53% points less likely to be enrolled in school (p < 0.01) and girls who engage in paid work are 31% points less likely to be enrolled (p < 0.01). This association came out strongly in the qualitative research. As some key informants remarked, there are very few educational institutions that cater for working children; once they enter the workforce, they generally cannot continue their education. Some of the girls in the qualitative sample were able to do home-based sewing to earn a supplementary income but the boys who were working were doing so outside the home on a full-time basis (except a few who helped out in their parents’ shop).

Young boys face pressure to drop out of school to start earning an income, whether they want to or not. The quantitative survey found that boys are more involved with paid work than girls: 29% of boys reported having engaged in paid work in the past 12 months compared to 20% of girls. Older boys were also more involved with paid work than younger boys (52% compared with 15%). Data also shows that increased work is aligned with decreased enrolment, with 86% of younger boys enrolled compared to 54% of older boys.

Families’ financial constraints lead to boys dropping out, especially if they are not doing well in school. This is accommodated by availability of informal paid work for boys. Adult men in community C felt that 70%–80% of children in the area dropped out of school because of poverty. According to one adult male respondent in community C, ‘doing badly in studies is also a cause of dropout. Then the family gives them pressure, saying that if you do badly at studies, you should eat by working. This is because of being less economically solvent.’ Parents also want boys to be involved in paid work rather than education so that they can contribute to the household finances. For example, a 16-year-old boy from community B migrated from Bhola (a poor remote island) with his parents, who put him to work so that they could control his income. According to the father of an adolescent boy in community B, ‘nowadays in Dhaka even 6-year-olds are earning thousands and thousands of taka [the local currency]. They work in multiple shops, they collect rubbish, they collect discarded iron parts, and they collect many different things. This is an income source for them.’ If we compare our three sites, most school dropouts and working adolescent boys are living in communities B and A. This is because these two communities are poorer, and different types of jobs (including street hawking and begging) are available there compared to community C.

Early Marriage

Bangladesh has the fourth highest rate of early marriage in the world, with 59% of girls married by the age of 18, and 22% married by the age of 15 (UNICEF 2020). Early marriage is an important barrier to girls’ education; as Table 3, column 3 shows, ever-married adolescents are 47% points less likely to be enrolled in school than their unmarried peers.

The GAGE survey found that across all three locations, 2.3% of all adolescents were ever married, with older girls the most likely to have ever been married at 11.8%Among older cohort girls who were married, the average age at marriage was 15 years; 40% of them had known their partner for less than a year. The majority (65%) were arranged marriages, and 73% of the 15 girls who had had an arranged marriage had agreed to it. Less than half (44%) of older cohort married girls were ready to be married. Unmarried older girls (15–17 years), on average, stated that they would like to get married at age 21 (range was from 17 to 30) and 12% mentioned that they would like to choose their spouse.

Table 4 presents the estimation results from the same model as in Table 3, but on a sample that is restricted to the older cohort of girls only. While educational aspirations among married and unmarried girls are not statistically different (column1), married girls are 28.5% points (47%) less likely to be enrolled in school than unmarried girls (column 2). Similarly, in the qualitative research, many respondents reported that while a few girls were able to continue studying after early marriage, some families do not let their daughter-in-law go to work or go back to school after marriage. Also, many schools do not encourage married girls to continue their studies.

The qualitative interviews found that family pressure and coercion both played a role in early marriage among adolescent girls. While parents and community members were aware of the negative consequences of early marriage for girls, some of the parents were motivated by social and cultural expectations and concerns. Financial constraints and costs of paying higher amounts of dowry were other motivating factors for early marriage, as generally, the younger the girl, the lower the dowry costs demanded by the groom and his family.Footnote 6 Interestingly, despite the fact that community C has less poverty and better schools than communities A and B, the rate of marriage among older girls was highest there, at 16%, compared to 14% in community B and 8.6% in community A.

Implications for Policy and Practice

We find that adolescents in urban low-income areas in Dhaka have high educational and professional aspirations, and their parents have high aspirations for them as well. Parental support for education is an important predictor both for current enrolment and grade attainment. Increasing aspirations for adolescents’ education in Bangladesh is a major achievement, reflecting government and NGO efforts over recent years to increase the value placed on education. However, actual levels of enrolment and retention do not reflect these aspirations; it seems that adolescent and parental educational aspirations are not being transformed into capabilities due to a range of social, economic, and institutional barriers. Location is an important predictor of aspirations and attainment, highlighting the importance of infrastructure and services, integration into the city, and stability of the community (including schools and facilities), along with higher incomes and better employment opportunities for households.

To address these gaps, policymakers should focus on ensuring that educational infrastructure, facilities and services (including secondary schools and vocational education centres) are provided equitably across all parts of the city so that all adolescents can enrol and complete secondary education. These facilities and services should be fully accessible to adolescents with disabilities, and have the necessary equipment and staff, including computer labs. While better-off families will be able to provide educational opportunities for their children through the private sector, it is essential that government provisioning compensates for differences in availability of educational infrastructure across different areas of the city.

Children and adolescents from poorer households need supplementary support and remedial education to attain the minimum standards so that they can finish secondary schooling; if they can achieve the required standards, their parents (and the adolescents themselves) will be more inclined to continue their schooling. Extracurricular activities, vocational training, and computer education in schools would provide poorer children with better opportunities and a broad range of skills, including life skills. Relatedly, school teachers and authorities should pay attention to the motivational aspects of schooling for boys and girls, so that they are more eager to continue and complete their education. Providing quality education with adequate stimulation through sports or cultural activities can increase boys’ motivation, who are most at risk to drop out due to lack of interest in education.

Finally, the education system should develop strategies so that adolescent boys at risk to dropout for paid work and adolescent girls at risk to dropout due to early marriage can continue their education. First, these strategies should support the development of policies and systems that enable adolescents to combine work and home responsibilities with schooling, as well as enable girls to continue education after marriage and childbirth. This includes innovative forms of schooling with flexible hours, combining general education with vocational education. Second, stakeholders (government and non-government) should also collaborate to implement comprehensive and multi-pronged interventions targeting the drivers of paid work and early marriage, focusing on secure housing, free schooling and basic services, and livelihood opportunities. In particular, greater access to vocational education would give adolescent girls an alternative to general education, which would help them develop market-related skills and provide them opportunities for earning incomes as an alternative to getting married. Moreover, stipends have been a key strategy of the Government of Bangladesh to increase educational attainment among adolescent girls (Hahn et al. 2018). Government policy is now being changed so that boys from poorer families who attend secondary school will receive stipends as well. Loans, stipends and other schemes targeting adolescents from the poorest families in the most poverty-stricken urban areas ease family financial constraints that drive adolescent dropout.

Change history

22 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00469-y

08 October 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00476-z

Notes

Due to the close timing of the household listing and quantitative data collection, there was little difficulty reaching selected households. In cases where the household was unavailable for interview or it was found that the adolescent was not eligible within our defined age range, other households were randomly drawn from each area to serve as replacements.

For more detailed discussion of the sampling methods and challenges in data collection, see Seager et al. (2021).

All of the authors were involved in the research design. Two were directly involved in collecting and analysing the quantitative data and three were directly involved in collecting and analysing the qualitative data.

Educational aspirations are commonly measured in other quantitative studies as the highest level of education desired, and have been found to correlate to higher educational achievement, even when aspirations are beyond what the adolescent expects or is achievable in the given labour market or context (Khattab 2014).

The adolescent’s raw Raven’s score ranges from 0 to 12, with a mean of 6.9. The raw scores are standardised to the sample mean and standard deviation, and included as a control.

Dowry is a payment usually given by the bride’s family and expected by the groom’s family upon marriage.

References

Appadurai, A. 2004. The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition. In Culture and Public Action, ed. V. Rao and M. Walton, 59–84. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Asadullah, M.N., A. Savoia, K.T. Sen 2019. Will South Asia achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030? Learning from the MDGs experience. ESID Working Paper No. 126. Manchester, UK: University of manchester, Effective States and Inclusive Development.

Baird, S., J. Hicks, N. Jones, J. Muz, and the GAGE consortium. 2019a. Dhaka, Bangladesh Baseline Survey 2017/2018. Adult Female Module. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence.

Baird, S., J. Hicks, N. Jones, J. Muz, and the GAGE consortium. 2019b. Dhaka, Bangladesh Baseline Survey 2017/2018. Core Respondent Module. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence.

Baird, S., J. Hicks, N. Jones, J. Muz, and the GAGE consortium. 2019c. Dhaka, Bangladesh Baseline Survey 2017/2018: Community module. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence.

Bangladesh Planning Commission. 2015. Millennium Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2015. Dhaka: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Planning Commission.

Banks, N. 2012. Urban poverty in Bangladesh: Causes, consequences and coping strategies. In Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper 178. Manchester, UK: University of Manchester.

Biswas, S., R. Azmi, S. Mowri, S. Ahsan, R. Sultana, and S.F. Rashid. 2019. Early Marriage Among Adolescent Boys and Young Men in Urban Informal Settlements in Bangladesh. In Dreaming of a Better Life: Child Marriage Through Adolescent Eyes, ed. G. Crivello and G. Mann. Oxford: Young Lives/International Development Research Centre.

Bradshaw, S., S. Chant, and B. Linneker. 2017. Gender and Poverty: What We Know, Don’t Know, and Need to Know for Agenda 2030. Gender, Place and Culture 24 (12): 1667–1688.

Cameron, S. 2010. Access to and Exclusion from Primary Education in Slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. CREATE (Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity). Research Monograph no 45, September 2010, University of Sussex, Centre for International Education.

CARE. 2016. The Cultural Context of Child Marriage in Nepal and Bangladesh. Geneva: CARE International.

Dalton, P.S., S. Ghosal, and A. Mani. 2016. Poverty and aspirations failure. The Economic Journal 126 (590): 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12210.

Del Franco, N. 2010. Aspirations and self-hood: Exploring the meaning of higher secondary education for GIRL college students in rural Bangladesh. Compare 40 (2): 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920903546005.

Dercon S., and A. Singh. 2011. From Nutrition to Aspirations and Self-efficacy. Gender Bias Over Time Among Children in Four Countries. Working Paper 71. Oxford: Young Lives.

Filmer, D., and L.H. Pritchett. 2001. Estimating Wealth Effects Without Expenditure Data––or Tears: An Application to Educational Enrollments in States of India. Demography 38 (1): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088292.

GAGE consortium. 2019. Gender and Adolescence: Why Understanding Adolescent Capabilities, Change Strategies and Contexts Matters, 2nd ed. London, UK: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence.

Genicot, G., and D. Ray. 2017. Aspirations and inequality. Econometrica 85 (2): 489–519.

Gorard, S., B.H. See, and P. Davies. 2012. The Impact of Attitudes and Aspirations on Educational Attainment and Participation. York, UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Greene, M.E., S. Perlson, A. Taylor, and G. Lauro. 2015. Engaging Men and Boys to Address the Practice of Child Marriage. Washington, DC: GreeneWorks and Promundo.

Hahn, Y., A. Islam, K. Nuzhat, R. Smyth, and H.-S. Yang. 2018. Education, Marriage, and Fertility: Long-Term Evidence from a Female Stipend Program in Bangladesh. Economic Development and Cultural Change 66 (2): 45.

Heath, R., and M. Mobarak. 2012. Does Demand or Supply Constrain Investments in Education? Evidence from Garment Sector Jobs in Bangladesh. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Heissler, K. 2011. ‘We are poor people so what is the use of education?’ Tensions and Contradictions in Girls’ and Boys’ Transitions from School to Work in Rural Bangladesh. The European Journal of Development Research 23: 729–744. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2011.40.

Hossain, N., and S. Hickey. 2019. The Problem of Education Quality in Developing Countries. In The Politics of Education in Developing Countries: From Schooling to Learning, ed. S. Hickey and N. Hossain. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

International Labour Office and United Nations Children’s Fund. 2021. Child Labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward. ILO and UNICEF, New York, 2021. License: CC BY 4.0.

Jones, N., L. Camfield, E. Coast, F. Samuels, B. Abu Hamad, W. Yadete, W. Amayreh, K.B. Odeh, J. Sajdi, S. Rashid, M. Sultan, E. Presler-Marshall, and A. Małachowska. 2018. GAGE baseline qualitative research tools. Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence, London, UK.

Jones, N., E. Presler-Marshall, A. Małachowska, E. Jones, J. Sajdi, K. Banioweda, W. Yadete, K. Gezahegne, K. Tilahun. 2019. Qualitative Research Toolkit: GAGE’s Approach to Researching with Adolescents. London, UK: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence.

Kabeer, N., S. Mahmud, S. Tasneem. 2011. Does Paid Work Provide a Pathway to Women’s Empowerment? Empirical Findings from Bangladesh. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

Karim, S. 2007. Gendered Violence in Education: Realities for Adolescent Girls in Bangladesh. Dhaka: ActionAid Bangladesh.

Khan, H., and J.B. Williams. 2006. Poverty Alleviation Through Access to Education: Can E-learning Deliver? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1606102.

Khattab, N. 2014. How and When Do Educational Aspirations, Expectations and Achievement Align? Sociological Research Online 19 (4): 7. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3508.

Kingdon, G. 2005. Where Has All the Bias Gone? Detecting Gender Bias in the Household Allocation of Educational Expenditure in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change 53: 409–452.

Mahmud, S., and S. Amin. 2006. Girls’ Schooling and Marriage in Rural Bangladesh. In Children’s Lives and Schooling across Societies, vol. 15, ed. E. Hannum and B. Fuller. Research in the Sociology of Education, 71–99. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT). 2014. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key Indicators. Dhaka: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International.

Presler-Marshall, E., and M. Stavropoulou. 2017. GAGE Digest: Adolescent Girls’ Capabilities in Bangladesh: A Synopsis of the Evidence. London: Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence.

Raj, A., M. Ghule, M. Battala, A. Dasgupta, J. Ritter, S. Nair, N. Saggurti, J.G. Silverman, and D. Balaiah. 2014. Brief Report: Parent–Adolescent Child Concordance in Social Norms Related to Gender Equity in Marriage—Findings from India. Journal of Adolescence 37 (7): 1181–1184.

Rashid, S.F. 2006. Marriage Practices in an Urban Slum: Vulnerability, Challenges to Traditional Arrangements and Resistance by Adolescent Women in Dhaka. Bangladesh: SSRN Electronic Journal.

Sarker, M.N.I., M. Wu, and M.A. Hossin. 2019. Economic Effect of School Dropout in Bangladesh. International Journal of Information and Education Technology 9 (2): 136–142.

Seager, J., S. Baird, J. Hamory Hicks, S. Faiz Rashid, M. Sultan, W. Yadete, and N. Jones. 2021. Finding the Hard to Reach: A Mixed Methods Approach to Including Adolescents with Disabilities in Survey Research. In Leaving No Child or Adolescent Behind. A Global Perspective on Addressing Inclusion Through the SDGs, ed. S. Chatterjee, A. Minujin, and K. Hodgkinson. London: Gender and Adolescence.

Strauss, J., F. Witoelar, and B. Sikoki. 2016. The Fifth Wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey: Overview and Field Report. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Thomson, R., M.J. Kehily, L. Hadfield, and S. Sharpe. 2011. Making Modern Mothers. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Thomson, R., and L. Hadfield. 2014. Day-in-a-Life Microethnographies and Favourite Things Interviews. In Steps to Engage Young Children in Research: Volume 2, The Researcher Toolkit, ed. V. Johnson, R. Hart, and J. Colwell, 126–130. Brighton: Bernard Leer Foundation, University of Brighton.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). 2012. Marrying too young: End child marriage. New York: UNFPA.

UNICEF. 2019. Education for adolescents. UNICEF webpage. https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/more-opportunities-early-learning/education-adolescents.

UNICEF. 2020. Ending child marriage. UNICEF webpage. https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/ending-child-marriage.

Wood, G.D. 1998. Security and Graduation: Working for a Living in Dhaka Slums. Discourse. Journal of Policy Studies 2 (1): 26.

World Bank. 2020. World Bank Development Indicators. World Bank webpage. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Due to an unfortunate oversight Jennifer Seager’s family name has been given incorrectly in the original version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sultan, M., Seager, J., Rashid, S.F. et al. ‘Do Poor People’s Dreams Ever Come True?’ Educational Aspirations and Lived Realities in Urban Slums in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Eur J Dev Res 33, 1409–1428 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00439-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00439-4