Abstract

Megaprojects are returning to play a key role in the transformation of rural Africa, despite controversies over their outcome. While some view them as promising tools for a ‘big push’ of modernization, others criticize their multiple adverse effects and risk of failure. Against this backdrop, the paper revisits earlier concepts that have explained megaproject failures by referring to problems of managerial complexity and the logics of state-led development. Taking recent examples from Kenya, the paper argues for a more differentiated approach, considering the symbolic role infrastructure megaprojects play in future-oriented development politics as objects of imagination, vision, and hope. We propose to explain the outcomes of megaprojects by focusing on the ‘politics of aspiration’, which unfold at the intersection between different actors and scales. The paper gives an overview of large infrastructure projects in Kenya and places them in the context of the country´s national development agenda ‘Vision 2030′. It identifies the relevant actors and investigates how controversial aspirations, interests and foreign influences play out on the ground. The paper concludes by describing megaproject development as future making, driven by the mobilizing power of the ‘politics of aspiration’. The analysis of megaprojects should consider not only material outcomes but also their symbolic dimension for desirable futures.

Resume

Les mégaprojets jouent à nouveau un rôle clé dans la transformation de l'Afrique rurale, en dépit de leurs résultats controversés. Si certains les considèrent comme des outils prometteurs permettant un «grand pas » vers la modernisation, d’autres critiquent leurs multiples effets néfastes et leur risque d’échec. Dans ce contexte, l'article revisite des concepts antérieurs qui ont expliqué les échecs des mégaprojets en faisant référence aux problèmes de complexité managériale et à la logique du développement dirigé par l'État. L’article s’inspire d’exemples récents au Kenya et fait un plaidoyer pour une approche différenciée, en prenant en compte le rôle symbolique que jouent les mégaprojets d'infrastructure dans les politiques de développement orientées vers l'avenir en tant qu'objets d'imagination, de vision et d'espoir. Nous proposons d’expliquer les résultats des mégaprojets en nous concentrant sur la «politique de l’aspiration», qui se trouvent au croisement entre les différents acteurs et les différentes envergures. L’article donne un aperçu des grands projets d’infrastructure au Kenya et les positionne dans le contexte du programme de développement national du pays, «Vision 2030». Il identifie les acteurs concernés et examine la manière dont les aspirations, intérêts et influences étrangères controversés s’articulent sur le terrain. L’article conclut en décrivant le développement des mégaprojets comme étant créateur d’avenir, sous l’impulsion du pouvoir fédérateur de la «politique de l’aspiration». L'analyse des mégaprojets doit tenir compte non seulement des résultats matériels, mais également de leur dimension symbolique qui forge un avenir attrayant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Africa is currently witnessing an unprecedented boom of investments in large infrastructure projects, commonly referred to as megaprojects. New roads, railways, airports, deepwater harbours, power lines, dams and irrigation schemes are mushrooming all over the continent. Megaproject development, as it seems, is implemented with the force of bulldozers, cutting corridors of economic growth into rural hinterlands and pushing the frontiers of modernization towards the margins. This present phase of spatial development began shortly after the year 2000, accompanied by large-scale land acquisitions and a ‘new scramble for Africa’ (Carmody 2011), and gained momentum when China announced its Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 (Chen 2016). A growing body of literature provides interpretations of the historical legacies of the ‘infrastructure scramble’ (Enns and Bersaglio 2019), highlighting the return of state-led development visions (Mosley and Watson 2016), modernist logics (Dye 2019), green economy (Bergius et al. 2020) and other forms of land investments (Lind et al. 2020), the emergence of a state-building frontier (Stepputat and Hagmann 2019) and the underlying fascination for ‘dreamscapes of modernity’ (Jasanoff and Kim 2015; Müller-Mahn 2020). Yet the resurrection of megaprojects is hard to understand in so far as large-scale projects have long been criticized for notorious under-performance and cost overrides, a phenomenon described as the ‘megaprojects paradox’ (Flyvbjerg et al. 2003). Against this backdrop, the question arises as to how we can explain the renewed fascination for ‘thinking big’ in spatial development, and the often rather meagre outcomes of megaprojects.

This paper takes cases from Kenya to investigate the political rationality and performance of megaprojects in the context of national development. Kenya is a particularly telling example, since it is the country with the highest concentration of large infrastructure projects in East Africa (Enns 2017). In line with a neoliberal, investor-friendly tradition, successive Kenyan governments have attempted to attract foreign and domestic capital, and to channel funds into showpieces of progress. Development corridors play an important role in this context, while national planning envisions transformation into a middle-income country. Recent studies have highlighted various aspects of corridor development in East Africa, such as territorial restructuring (Greiner 2016), societal exclusion and inclusion (Chome 2020), complex rural responses (Enns 2017, 2019), diverse forms of knowledge production and resistance by rural land users (Enns and Bersaglio 2020), the use of discursive tactics and spatial imagination (Aalders 2020), and the importance of corridors as instruments for the expansion of global value chains (Dannenberg et al. 2018).

The paper contributes to the debate on megaproject development by highlighting an aspect, which has attracted relatively little attention. We propose to view megaprojects as huge constructions that explicitly affect the future, or more specifically, as tools of ‘future-making’ in the sense proposed by Appadurai (2013). Appadurai distinguishes anticipation, imagination and aspiration as cultural practices that make the future an issue in the present. While anticipation refers to probabilities, and imagination to designs and collectively held beliefs, aspiration aims at desirable futures, possibilities and hope. Thus, we assume that aspiration is important for understanding how megaprojects are conceived and performed as promises of future improvements, as pathways to modernity, and—to use a metaphor—as ‘beacons of hope’. We propose to consider megaproject development as part of the ‘politics of aspiration’, in which hope is produced and performed in public debates, political negotiations, and planning processes.

The history of large-scale projects in Africa saw a first boom after independence, when national development followed visions of modernity and state-driven development and was aimed at rapid societal transformation (Scott 1998). The character of large infrastructure projects changed substantially after the neoliberal turn in the 1980s. With the roll-back of the state, ‘the envisioning of megaprojects was limited to those that could at least be partially funded by the private sector’ (Schindler et al. 2019: 2). Today, megaprojects are back on the political agenda, but embedded in complex institutional settings. They involve governmental and non-governmental actors, the private sector and international funding agencies, resulting in a more decentralized and partially fuzzy governance structure (Mosley and Watson 2016).

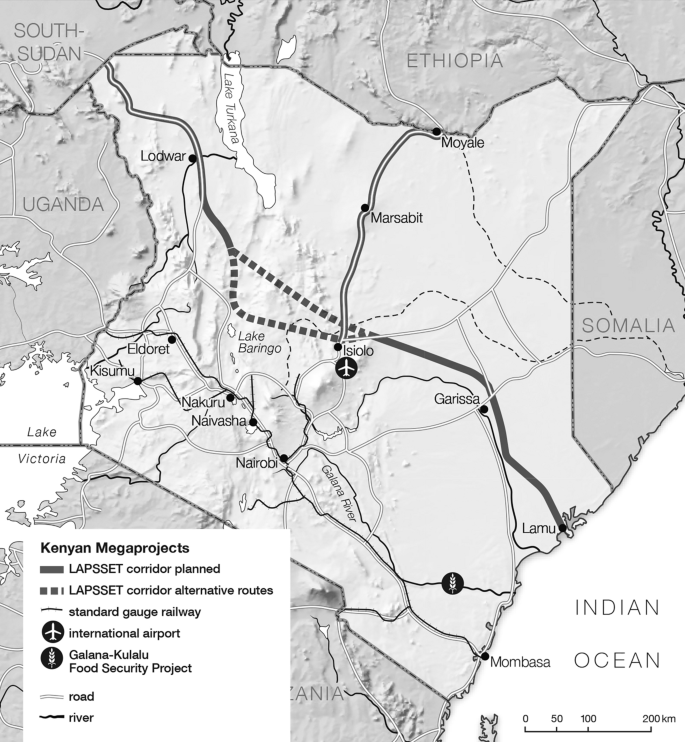

We will first explain our conceptual framework in respect of the so-called ‘megaproject paradox’ and the significance of aspiration. Then we will present three cases of megaprojects in Kenya: the standard gauge railway from Mombasa to Nairobi, the LAPSSET corridor with the construction of an international airport and an abattoir at Isiolo, and the Galana-Kulalu Food Security Project. In the discussion, we will come back to the question formulated in the title of this paper by looking at the relationship between the politics of aspiration and the outcome of such megaprojects.

Conceptual explanations for the success or failure of megaprojects

The history of problematic megaprojects may be traced back to the Tower of Babel, which became a metaphor for over-ambitious construction schemes ending up in chaos. Until today, megaproject developments arouse ambivalent feelings, fluctuating between enthusiasm and scepticism. James Scott (1998), in his seminal work entitled Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed, presents a number of cases exemplifying the ‘fiasco’ and even ‘full-fledged disaster’ of large state-led projects. Yet there are no absolute criteria for characterizing a project as ‘mega’ or as a failure, since these are both relative terms. Megaprojects may be viewed as huge development schemes which are particularly ambitious, expensive, and difficult to manage, with a tendency to fail to meet the initial objectives (Schindler et al. 2019). On the basis of a literature review, we distinguish four conceptual approaches to explaining the outcome of megaprojects.

The first of these four approaches focuses on the complexity of large-scale engineering projects, which are generally difficult to manage and control (Salet et al. 2013). Flyvbjerg et al. (2003) present a number of spectacular multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects, such as the Channel Tunnel, Denver International Airport, and other examples in the Global North, which started with high-flying expectations and ended up with extreme cost-overruns. The examples highlight the gap between promises and achievements, a phenomenon the authors call the ‘megaprojects paradox’. They argue that the disappointing performance of megaprojects is not accidental, but part of the project logic. Exaggerated promises, weak governance structures, lack of control, and insufficient accountability serve to generate exceedingly high profits. In sub-Saharan Africa, this combination of problems is all too common (Sobják 2018).

A second line of explanation links the outcome of megaprojects to political regimes and the state. Scott (1998) relates the failure of large-scale development schemes to a combination of several elements culminating in ‘high modernism’, i.e. a system of beliefs that relies on science and technology, the transformation of nature, and the power of authoritarian states. On the basis of case studies of large schemes from various parts of the world, including an example from Tanzania, Scott argues that ‘it is the systematic, cyclopean shortsightedness of high-modernist agriculture that courts certain forms of failure’ (Scott 1998: 264). State-led, top-down projects do not work, because they do not fit into local conditions. This argument is supported by recent studies on high-modernist megaprojects on the African continent. Van der Westhuizen (2007), for example, points to the importance of political symbolism to explain the costly construction of Gautrain, a metropolitan high-speed train network in South Africa, which was aimed not only at improving public transport but also at presenting South Africa as a modern state on the occasion of the 2010 Football World Cup. Ballard (2017) interprets housing schemes in South Africa as attempts to strengthen the legitimacy of the state, especially in the context of upcoming elections. This explains why housing megaprojects serve other interests beyond their material dimension. Ballard and Rubin (2017) attribute the shift from small to big housing schemes to the ‘megaprojects policy turn’ in South Africa in the years 2014–2015. In a similar vein, Hannan and Sutherland (2014) explore controversies around urban megaprojects in Durban, South Africa, which they attribute to conflicts between short- and long-term goals, and between pro-poor and pro-growth orientations. Projects are criticized for high economic risk, frequent delays, lack of transparency and accountability, and as ‘elite playing fields’ (Hannan & Sutherland 2014: 2).

A third argument points to the vulnerability of megaprojects in the context of social and economic change. Ansar et al. (2017) give an overview of ‘theories of big’, which they interpret as a tendency to undertake ever bigger projects under conditions of economies of scale. They argue that, contrary to their ambitious goals, big projects are characterized by a particularly high degree of ‘fragility’ due to their exposure to uncertainties. The authors conclude that ‘to automatically assume that “bigger is better”, which is common in megaproject management, is a recipe for failure’ (Ansar et al. 2017: 3).

Finally, a fourth approach highlights the symbolic dimension of large-scale infrastructure projects, especially regarding their role as symbols of progress and focal points of aspiration. Megaprojects capture the imagination, they are ‘imagined before they come to exist’ (Schindler et al. (2019: 2), and in doing so, they create ‘imagined futures’ (Beckert 2016) which serve as pacemakers of development. Imagined futures may become effective drivers of change, if the imagination is shared by a sufficiently large number of actors, based on the promises of transformation, and the ‘enchantments of infrastructure’ (Harvey and Knox 2012). The power of megaprojects comes not only from their physical impact but also from the power they exert over the minds of the people affected by rural transformation. Thus, they may be considered as aspirational projects aiming at ‘dreamscapes of modernity’ (Jasanoff and Kim 2015; Müller-Mahn 2020). Such aspirations promote speculation and jostling for position, which can easily lead to conflicts (Elliot 2016). Further, interference with land rights, ecology and social conditions may lead to project delays if these injustices are protested. Lastly, the projects may be impractical, since they are largely driven by elite imaginations with little attention to participatory processes involving the local communities. This suggests that local input is not only morally desirable but also practically necessary (Stetson 2012; Mkutu et al. 2019).

Development planning in Kenya

The first megaproject in Kenya was the nearly 600-mile-long railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria, constructed in 1896–1901, which aimed to consolidate British control in the region and succeeded in opening up the southern part of Kenya (Jedwab et al. 2015). In the postcolonial period, there was an intermittent focus on infrastructural development as a driver of economic growth. After independence, Kenya’s economic policy was formulated as African socialismFootnote 1—although it was in fact a mixed economic policy, focusing chiefly on high potential areas (Zelezer 1991). Later policies briefly favoured redistributive ideals, and then donor-driven structural adjustment policies took over in the 1980s in which the private sector and civil society were seen as key drivers of growth. Policies produced during this period were aimed at employment opportunities in industry and agriculture, while roads, power and water supply were prioritized. Industrialization continued to be emphasized in the 1990s and again in the 2000s.

The year 2008 saw the creation of Kenya’s Vision 2030 whose aim was the pursuit of global competitiveness and prosperity in order to offer Kenyans a high quality of life by 2030. Key features of the plan include investment in the arid and semi-arid lands (ASAL), focusing on infrastructural development to connect different parts of the country through roads, railways, ports, airports, waterways and telecommunications, which would then stimulate private sector investments. The first medium-term plan (MTP) of Vision 2030 (2008–2013) outlined the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project. According to claims by the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, the corridor will ‘inject between 2 and 3% of GDP into the [Kenyan] economy’. Officials further estimate that LAPSSET might even yield higher growth rates ‘of between 8 and 10% of GDP when generated and attracted investments finally come on board’.Footnote 2 These claims lie behind the project slogan: ‘Building Africa’s Transformative and Game Changer Infrastructure to Deliver a Just and Prosperous Kenya’. As Browne (2015:7) rightly points out, LAPSSET ‘echoes the modernist developmental approach of African governments in the 1960s but differs from the infrastructural visions of the past in both its magnitude and rationale’. It is part of a continent-wide ambitious development vision, which copies models of transboundary integration and modernization from Europe and North America (Chome et al. 2020).

In 2012, in line with Vision 2030, the government produced Sessional Paper No. 8 of 2012 ‘National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Northern Kenya and other Arid Lands’, which deliberately focused on reversal of the previous policy of concentrating development efforts on high potential areas. The paper articulated the need to close the gap between these areas and the rest of the country, while at the same time protecting and promoting the mobility and institutional arrangements which are so essential to productive pastoralism amidst the threat of climate change and the need for food security. The paper acknowledged the potentials of ASAL regarding cross-border trade, livestock, tourism, natural minerals and renewable energy, with special mention of the LAPSSET project.

The second MTP (2013–2017) continued to emphasize infrastructure development, amongst others, while the third MTP (2018–2022) prioritizes a so-called Big Four Agenda: food security (which includes irrigation and development of the blue economy), affordable housing, affordable healthcare for all and manufacturing (which includes creation of special economic and industrial parks and increasing agro-processing). Additionally, it proposes oil and minerals development, and the expansion and modernizing of infrastructure. These plans are considered inclusive by virtue of the devolved structure now in place following Kenya´s 2010 constitution.

One problem with this timeline of Kenya’s visions is that implementation is characteristically poor (Zelezer 1991). Referring specifically to the LAPSSET project, Browne (2015) comments that there have been delays in implementation, confused and sometimes contradictory announcements, and many concerns over land grabbing and compensation issues, as well as social and environmental impacts, raised by a very active civil society. Below, we present a number of case studies as examples of megaproject development in Kenya.

The case of the Standard Gauge Railway

The 485 km long Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Nairobi to Mombasa was completed in 2017 as Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since independence.Footnote 3 It was funded and built by the Chinese at a cost of $3.2 billion US dollars loaned from China Exim Bank and is also operated by the Chinese.Footnote 4 As of June 2019, Kenya owes $6.5 billion to China following the further extension of the railway to Naivasha,Footnote 5 but China declined further loans to take the railway to Kisumu as originally planned.Footnote 6 The project has been mired in controversy due to the non-competitive manner in which the Chinese company was awarded the tender.Footnote 7

The final terminus of the SGR is to be a dry port in Maai Mahiu near Naivasha town, partially occupying land which was privately grabbed by high ranking politicians.Footnote 8 Around 40 km away in Suswa town, Narok County, 405 ha of land is being set aside for an industrial park.Footnote 9 The SGR was intended to recoup its costs through cargo transportation, although so far it is mainly a passenger service. In September 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Infrastructure issued a directive that all cargo be transported by rail on the new railway from Mombasa to Nairobi and on to Naivasha, thus, bypassing Mombasa town. This met with strong protests over the loss of thousands of jobs in clearing and forwarding agencies, and in the fuel and transport sectors, and a shrinkage of Mombasa’s economy by over 16%.Footnote 10 The directive was subsequently officially suspended in October 2019,Footnote 11 likely due to pressure from elites who own trucking companies operating between Kenya and the Great Lakes countries.Footnote 12

A World Bank report highlights numerous negative impacts of the SGR project in Narok, such as increasing crime and prostitution, pollution and deforestation, with particularly severe consequences for local pastoralists.Footnote 13 An estimated 10,000 families are expected to be displaced by the inland container depot and associated developments. A Maasai community went to court to oppose the developments, saying that the 1619 ha they were offered to replace their land is insufficient.Footnote 14 The shaky provisions for compensation of community-land owners have been described, but the enactment of the Land Value Index Act (2018) has made it even more difficult to get timely and adequate compensation. The Act is meant to prevent delays over compensation disputes by allowing the government to go ahead with the project as cases are resolved, but there are concerns that this could also allow community rights to be overridden more easily. Further, the Act only recognizes the market value of the land, and it only acknowledges permanent occupiers, which is insensitive to pastoralist realities and the value of the land for pastoralist livelihoods. Currently, compensation is marred by corruption, including the taking of bribes by Maasai elites.Footnote 15 Furthermore, some influential persons, including members of parliament, have bought land cheaply from locals and sold it at exorbitant prices to the Chinese company constructing the SGR. In Suswa, one man’s farm was bought for KES 40,000 (USD 400) and sold on for millions. It is expected that land sales will continue to increase in the area in which former Maasai group ranches have been extensively subdivided.Footnote 16 When interviewed, a Maasai elder explained his fears concerning the loss of pasture and water in the Kedong valley in which Suswa town is located:

Changes are coming, the previous life we were living seems to be gone… We might have to start zero grazing (bringing cattle feed), when Kedong is gone… Now we are being pushed out. What will happen? People will suffer...our living will be like Kibera (slum in Nairobi).Footnote 17

This case illustrates how weak land laws allow elites to benefit from infrastructure developments at the expense of marginalized citizens. Poor planning of such a huge project, which is at the same time dominated by elite visions, caused the project to become a financial failure and transferred the debt burden to future generations of Kenyan taxpayers.

LAPSSET projects: Isiolo International Airport and Abattoir

Like the SGR, projects in the LAPSSET corridor such as the upgrading of the small airfield of Isiolo to an international airport have raised temperatures over land rights, with irregularities in respect of land acquisition, resettlement and compensation. Covering an area of 260 ha, the airport terminal lies in Isiolo County, while the runway extends into Meru County. The total cost for the Kenyan government amounts to 27 million US dollars. At its opening, the airport was heralded as a ‘game changer’ for the economy of the northern counties. However, the airport, which had been built for over 6000 passengers per week, currently operates far below its capacity, handling only one small weekly flight (Atieno 2019). Moreover, the airport is still not equipped to handle commercial or cargo flights because it lacks a control tower, landing lights and a sufficiently long runway.Footnote 18 One of the immediate challenges has been the downturn in the global demand for the soft drug miraa (also known as khat), which was banned in Europe in 2017. The plant is grown widely in Meru, and it was anticipated that the trade in miraa would benefit greatly from the facility. Another challenge has been delay in the completion of the Isiolo abattoir, to be discussed below (Atieno 2019). Thus, the current failure of the airport is related to its complex interdependency with other segments of the LAPSSET megaproject.

The airport was built on trust land—an old designation referring to land owned on a communal basis, often by pastoralist groups, and held in trust by local authorities. Such land was compulsorily acquired by the government or grabbed by elites, sometimes in league with local councils, as rights holders were rarely aware of their rights to consultation, appeal and compensation or relocation, and had little capacity to fight for them. The Land Act of 2012 and the Community Land Act of 2016 re-designated trust land as community land and strengthened the legal framework for its users, providing for registration by communities. This will protect them against land grabbing and allow direct compensation in the event of compulsory government acquisition. However, the process of implementation of this law is slow, even as the pace of change in northern Kenya is rapid.

In 2004, a team of councillors and elders was appointed to look at the number of people who would be affected by the airport project.Footnote 19 A ballot process for which people paid KES 1000 (USD 10) was used to allocate replacement plots to displaced residents. However, initial estimates of those displaced swelled, and the situation became increasingly complicated. Outsiders also benefited from allocations.Footnote 20 In a World Bank report, a former county council administrator described the confusion:

The initial 700 were to be relocated to Mwangaza, but the number increased over time to 1,500. As a result, some of the people were relocated to Kiwanjani location (Wabera Ward) but there were only 450 plots, and 50 squatters were already occupying the area, so approximately 400 in number were to move to Chechelesi, which had 1,900 plots. However, although the ballot was done, no land has yet been given out. Tension resulting from political interference and the change of leadership meant that even the Mwangaza area has not yet been occupied by the allocated people …. It’s now more than politics and has turned into a blame game.Footnote 21

The process was marred by delays and also by double allocation of new plots, which is the result of both corruption and confusion. The situation was further complicated by devolution. Several plots were acquired by elites following the passing of the mantle from the former Isiolo County Council to the County Government in 2013. A bishop estimated that there were around 100 internally displaced households as a result of the flawed relocations, and he believed that the new county government had behaved irregularly. Chiefs and ward administrators concurred that the county government had grabbed and consolidated 10 to 20 plots that were balloted, and later prepared a new fake map to facilitate the sale or gift of the plots to their cronies, especially in the Chechelesi area. Illegally produced and invalid documents were given out. In the words of a local chief, ‘the problem is corruption within the land office’.

Several respondents warned of the potential for ethnopolitical conflict as a result of the airport expansion. The runway extends into Nyambene in Meru County, where people who lost their land for construction purposes have been compensated, while those affected in Isiolo have not, because here the land was trust land. This plays into an existing volatile boundary dispute between Isiolo and Meru counties which has already been exacerbated as a result of LAPSSET, since the boundary determines which county benefits from compensation and economic development in the disputed area.

Interestingly, a top official from the Vision 2030 directorate denied in an interview that genuine people had not been compensated and reiterated that LAPSSET is a game changer with positive effects for the local population.Footnote 22 This viewpoint fails to acknowledge that not everyone is a winner from this project, and that shared prosperity may remain a dream due to institutional weaknesses, corruption, elite capture and pre-existing ethnopolitical competition.

Another example to illustrate the complexity of activities tied into the LAPSSET corridor is the construction of an abattoir at Isiolo town. Isiolo Holding Ground (also known as Livestock Marketing Division or LMD) is a 124,200 ha site, occupying parts of Burat and Oldonyiro wards, and bordering Laikipia, Samburu and Meru counties (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Marketing, 2006). It was established by the colonial government as a disease control buffer zone for protecting settlers’ cattle from pastoralist cattle migrating southwards during times of drought, and for quarantining and livestock marketing purposes. The ground continues to be used for quarantining and disease screening, as well as fattening and watering, but for some years it has not been operating as effectively as intended, due to poor management, land claims and overgrazing. It is occupied by a number of users including different armed pastoral groups belonging to Dorobo (iltorrobo, hunter gatherers turned Maasai), Samburu, Turkana, Meru and settled Somali communities.

In line with other planned developments in northern Kenya, the new abattoir is expected to boost the economy of the north through meat export and to allow farmers to receive direct payment for their livestock without being exploited by middlemen. It has the capacity to slaughter 1000 sheep and goats, 200 cows and 100 camels daily. Realization of the vision was delayed due to lack of funds provided by the previous county government and poor workmanship, but there are hopes that private investment and World Bank funds may help to make up the shortfall.Footnote 23 In an interview, an official from the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority was very positive about the potential for international export of animal products, saying that ‘this abattoir will be one of the major economic achievements that can facilitate growth along this corridor especially within the pastoralist counties’.

In contrast to the airport, there was a general sense of optimism and hope amongst many community members regarding the abattoir. It may be that this aspect of Vision 2030 is truly appropriate to local needs and more likely to bring shared prosperity, once the problems have been overcome. Further, its potential success does not rely on other infrastructural developments, although it does harmonize with the airport plans. Some concerns remain, however, such as a potential rise in conflict due to the large number of people from different ethnic groups settled in the LMD, so that the improved market for livestock could potentially exacerbate cattle raiding for cash.Footnote 24 Lastly, Isiolo abattoir was initially envisioned to serve the neighbouring counties, but the governments of three other counties have decided to build their own.

Galana-Kulalu: a failed ‘million-acre’ food security project

Large-scale agricultural development schemes are not new in Kenya. From the mid-1950s, the colonial government sets up the Perkerra, Hola and Mwea-Tebere irrigation schemes on ‘native reserves’. After independence, the Ministry of Agriculture took over the management of these projects, and in 1966, the National Irrigation Board (NIB)Footnote 25 was established with the mandate to develop, improve and manage national irrigation schemes in Kenya (Ngigi 2002). NIB spearheaded the development of Ahero, Bunyala, West Kano and Bura irrigation schemes between the mid-1970s and early 1980s.

Closely related to these projects is the million-acre idea, which is traceable to the early 1960s when focus shifted to the re-Africanization project dubbed the ‘million-acre settlement scheme’. It targeted lands that the colony had previously set aside for European settlement (Bradshaw 1990; Chambers 1969; Kanyinga 2009; Leo 1981). The million-acre scheme aimed at land redistribution and conferment of tenure rights on indigenous communities for settlement and agricultural development, while the large irrigation schemes were a response to food security challenges and the management of risks associated with unpredictable rainfall patterns. Irrigation and settlement schemes are driven by the politics of aspiration, because their purpose goes beyond addressing the underlying challenges. Essentially, they are central to the realization of the independence dream and are, thus, designed to win the support of the masses and to draw potential international development aid. The big promises justified external financing of such projects. For example, between 1977 and 1986, the World Bank financed the Bura Irrigation Project to the tune of USD 40 million.

To what extent have these centralized projects lived up to expectations? About six decades on, most public irrigation schemes in Kenya perform way below average (Muema et al. 2018). Ngigi (2002) notes that ‘the intended benefit of improving the living standards, to say the least, has not been realised’ and that some, like Bura, are no longer functional. Moreover, some irrigation schemes and large-scale agricultural investments are linked to human rights abuses especially through land dispossession (Otieno 2016). However, central to the failure of these schemes is the complexity of management and control as exemplified by Flyvbjerg et al. (2003). Bradshaw (1990) blames this on challenges around ownership, management, uneven resource distribution, water allocation and scarcity, which contribute to underdevelopment.

In 2010, as part of Vision 2030 and in line with UN goals,Footnote 26 Kenya embarked on a renewed push for the return of mega irrigation projects. Arguably, these visions and imaginations of the future are essentially anchored in global discourses and existential threats, which helps to give them currency and a strong bargaining position in the state decision-making apparatus. Despite the proven failure of the schemes already discussed, the idea of megaprojects was presented afresh, with renewed fascination and new aspirations that captured the imagination of the masses, as well as that of development partners, capitalizing on their link to the country’s development blueprints within the internationally favoured devolved governance structures.

Nine large-scale schemes were identified, three of which became flagship irrigation projects: the Galana-Kulalu Food Security Project (GKFSP), Mwea Irrigation Development Project and Bura Irrigation Rehabilitation Project. The GKFSP is more recent than the others, having been launched in 2014 with completion planned for 2017. The project was one of the key campaign promises that the Jubilee administration made in its manifesto. The idea was to make Kenya a food-secure nation through the one-million-acre land irrigation initiative (Leshore and Minja 2019). Below, we will describe the nature of the project and the conditions under which this massive agricultural investment collapsed.

The project was planned to be implemented in three phases: a Model Farm of 10,000 acres, to be developed into a Pilot Farm covering 100,000 acres, and finally the larger GKFSP with 1.75 million acres (NIB 2015). As located in one of Kenya’s poorest, semi-arid counties, the proposed million-acre irrigation scheme promised to secure the country against hunger, increase agricultural exports and transform a previously ‘underutilized’ landscape through large-scale production of maize, sugarcane, vegetables and fruits, and through market-oriented livestock production for both local and international markets. Water from the Galana River was meant to irrigate hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland located primarily within the controversial Agricultural Development Corporation (ADC)Footnote 27 land at Kulalu ranch. Such a massive project required big financing and technical expertise that exceeded the country’s capacity. Through NIB, the Kenyan government engaged Israel’s leading agricultural consulting firm, Agri-Green Consulting Ltd, for technical and operational support. The selection of this firm went along with financial assistance from Israel for implementation of the project and to cement Israel-Kenya relations. In September 2014, the government awarded Agri-Green Ltd the contract at KES 14.5 billion (USD 145 million), which was later revised down to KES 7.2 billion (USD 72 million). Popular opinion has it that the contract may have been deliberately overpriced for personal gain.

The launch of the project elicited much excitement and expectations that a previously ‘forgotten’ space could become the engine for national food security. However, this anticipation would soon turn into heated criticism and resistance, particularly from coastal Kenya, where the project is located. Expectations of job opportunities for young people were disappointed, leading to feelings of betrayal and deception, as elite-owned consulting firms controlled even the lowest jobs, like bush clearing. From the onset of the project, there was strong centralized management, which meant lack of ownership and support at the local level. Such grievances quickly led to crime and insecurity, as armed groups in the region expressed their displeasure over the agricultural investment. The location of the project next to the Tsavo East National Park also meant that a new frontier for human-wildlife conflict was created, coupled with increasing cases of poaching. This begs the question whether the state and other stakeholders bothered to consider the possible consequences of such a massive investment. It would appear that fascination with the scheme blinded its founders to the realities on the ground: ongoing conflicts between Orma pastoralists and the management of Galana-Kulalu ADC ranches over grazing land; human-wildlife conflicts; challenges of service delivery; poverty and poor education (NIB 2015).

Other contextual and politico-economic factors that are blamed for the slow pace of the project and its eventual collapse include poor road networks, mismanagement of funds, and lack of basic amenities like electricity, potable water and health facilities.Footnote 28 Indeed, this marginalized area had deep-seated problems and social inequalities that needed serious state intervention before setting up such a huge project. However, it seemed as though there was a rush to push the financing through to demonstrate that the political regime was working towards its development goals. The ease with which billions of shillings were disbursed within a very short period of time in contrast to the quality of work done became the greatest point of public concern. For example, the Senate Agricultural Committee probing the stalled Galana-Kulalu model farm learnt that the government paid KES 580 million for bush clearing on only 10,000 acres of land, a job that was apparently done to a poor standard.Footnote 29 According to NIB, at least KES 6.1 billion was paid to the contractor out of which KES 2.55 billion was paid by the government of Kenya.Footnote 30 The lack of tangible results for the money spent raised public suspicion, as noted in a national newspaper:

The project was a good idea but now it seems difficult to avoid the conclusion that it ended up being a cash cow for a few individuals… the expected production from the project turned out to be about a quarter of what had been expected. This, after more than Sh5 billion has been spent on the project. How could a project to be carried out on 1.75 million acres and having the engagement of a firm from Israel – which is renowned for its success in dryland agriculture and advanced irrigation techniques – have failed?Footnote 31

Some critics have interpreted this feeling of deception among the inhabitants of the region as a deliberate strategy by the state to undermine development in coastal Kenya and thus weaken its political relevance. The NIB links the failure of the project to the lack of capacity on the side of the contractor, Agri-Green Consulting Ltd, yet the firm had a strong record of delivering similar projects in worse ecological conditions and it was the responsibility of NIB to vet the firm’s capacity before awarding the contract. Israel’s envoy to Kenya, Noah Gendler, resigned after barely two years in the job, noting that he had ‘failed to add value to the country’. He linked the failure to political and economic sabotage, particularly by farmers and their politicians in Kenya’s maize growing areas, and pitiless cartels involved in maize importation, both of whom thrive on shortages that allow them to reap billions. The scheme, according to him, was the first ever in the history of Israel’s government-to-government development projects to fail.Footnote 32 Despite the failure, neither the government nor the contractor has accounted for the billions of shillings lost.

Notwithstanding the big promises made by the state and the high expectations of the local communities, Galana-Kulalu adds to the list of failed large-scale irrigation projects in Kenya. A similar story comes from the Napuu II irrigation scheme in Turkana County, which seems to have even intensified hunger.Footnote 33 Likewise, the Tana Delta Irrigation Project, which was funded through the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), failed to achieve its intended promise, though the Tana and Athi Rivers Development Authority (TARDA) invested KES 70 million (US$ 700,000) to rehabilitate the collapsed scheme.Footnote 34 The Perkerra irrigation scheme is also reportedly on the brink of collapse due to insufficient water supply. Nevertheless, NIB continues to line up dozens of large irrigation projects for funding, whilst facing a political tussle revolving around the governance and management of projects in specific devolved units.

The example of Galana-Kulalu illustrates how the state originally envisioned massive agricultural investment as promising quick economic and social transformation, which then became overcomplicated and suffered from a lack of accountability and other institutional deficiencies. As a response, the state and some politicians sold part of the scheme to private investors, convinced an international partner to participate in providing technical solutions, and attracted foreign donor assistance. The over-ambitious imaginations around the project blinded its makers to unintended consequences, accountability or possible failures. Similarly, in their review of three large dams in West Africa, Bazin et al. (2017) note that decisions to invest in large dams and irrigation schemes are not always based on realistic hypotheses. Instead, they argue, initial design studies often rely on overestimated assessments of irrigable potential or economic performance of irrigation projects, or under-estimate their cost and the time needed to realize them, in order to make the economic case for a project. For Kenya, such has been the game, where rushed projects end up failing due to contextual and political economy factors.

Discussion: megaproject ambiguities

What do the Kenyan examples tell us about megaprojects and failed developments? The following aspects are key to explaining the often rather ambiguous outcome of megaprojects, the role of aspiration and the meaning of failure.

First, we would argue that the older conceptual approaches mentioned at the beginning of this paper need to be critically revisited in the light of recent developments and scientific debates. Management problems do of course play a role, as observed by Flyvbjerg et al. (2003), but this does not sufficiently explain why projects go wrong. Likewise, Scott’s (1998) analysis of the state as an authoritarian modernizer does not capture the complexity of governance systems, as Li (2005) has pointed out, and it has little to do with Kenya (Mosley and Watson 2016). Instead, we believe that it would be more appropriate to describe the role of the Kenyan state as moderating the interplay between multiple actors in cross-scalar connections, and seeking to create an investor-friendly climate.

Second, our analysis highlights the symbolic dimension of megaprojects as showcases and ‘dreamscapes’ of modernity (Jasanoff and Kim 2015; Müller-Mahn 2020). They serve as strategic tools to foster optimistic outlooks and ‘fictional expectations’ (Beckert 2016), thus, taking centre stage in the politics of aspiration. A telling example is the Galana-Kulalu scheme, which Kenyan public media presented as the ‘new food basket’ of the country.Footnote 35 It is important to note that megaprojects contribute to future making, regardless of whether they achieve their declared goals or not.

Third, using the politics of aspiration does not mean that planners and politicians are blind to risk, but it explains why they often do not tell the whole story, or prefer to talk about ‘chance’ instead of ‘risk’. Decision makers tend to take an attitude of ‘wishful thinking’ by presenting and performing ‘desirable futures’ as if they were real, because it helps to convince investors, donors and local populations. The ‘enchantment’ of large infrastructures (Harvey and Knox 2012) is used to justify risky investments, while fuzzy time frames make it almost impossible to measure project delivery. As long as the promised future has not (yet) arrived, one cannot say that a megaproject has definitely failed.

Fourth, megaprojects hardly ever end with complete success or failure, but somewhere in between. To do justice to the complex setting, the performance of megaprojects should be assessed relative to the promised benefits. In the same vein, projects should be evaluated relative to time, i.e. accepting that there may be good reasons if they fail to deliver on the promises and within the expected timeline. Failure may have many causes which are not necessarily part of the project itself, but may be due to its complex environment and the conflicting visions of the multiple actors involved. In the case of the SGR, for example, the section from Naivasha to Malaba cannot be completed because of debt, Tullow Oil’s uncertain stake in Turkana, and several changes of the LAPSSET route and resort city sites. When building the international airport at Isiolo, planners could not foresee that the export of khat, one of its purposes, was going to be banned. In the building of the Isiolo abattoir, it was not foreseen that other counties would want to build their own, using their devolved funds, with the result that the abattoir may never function to capacity. In some cases, projects are deliberately delayed to serve other political purposes. For example, previous presidents have used slogans like ‘Kazi iendelee’ (work should continue) during their re-election campaigns, to indicate that their regime needs another term in power in order to realize their promises—which either never happens or provides the impetus for more promises.

Fifth, megaprojects are characterized by lack of accountability, which can best be seen in the case of the Galana-Kulalu scheme. For LAPSSET as a whole, the promises and economic returns were deliberately overestimated. So far, only the SGR, one berth of Lamu port, and a road from Isiolo to Moyale have been completed and have resulted in large debts and unpaid compensation claims. This is far less than originally planned, but the promises served their purpose.

People imagine megaprojects as if they are already complete—without factoring in the complexity, local conditions, and the hidden risks and agendas. Indeed, such imaginations contribute enormously to shaping and changing both space and people’s lives. In the cases discussed here, expectations concerning infrastructure such as valorization of land and other previously peripheral resources became the basis for communal land subdivision, commodification and privatization. This change of social arrangements follows the popular narrative that people are ‘leaving the rural behind’ and jumping into modernity. The meanings and aspirations that people at the local level associated with these megaprojects as systems to enable the circulation of goods, knowledge, meaning, people and power (Graham and Marvin 2001), have been reduced to mere hopes.

However, as one might argue, if all potential challenges were foreseen, nothing would ever get off the ground. If planners in early colonial times had listened to criticisms of the Kenya-Uganda railway, the ‘train from nowhere to nowhere’ would never have led to the development of the interior, albeit with violence and injustice. Thus, while big unrealistic visions may be useful for mobilizing action, they simultaneously offer opportunities for everyone to aspire to effective participation and address the structural injustices upon which these projects are often superimposed. Despite the challenges, setbacks and perceived failures, these very visions of development, prosperity and independence ironically shape contemporary economic and sociol-political discourses, as well as development partnerships. Big promises and megaprojects continue to be powerful tools that legitimize massive external borrowing, the burgeoning foreign debts notwithstanding.

In conclusion, we have shown that certain megaprojects in Kenya started with over-ambitious goals, which they failed to meet during implementation. Even so, a critical assessment of megaprojects should focus not only on material outcomes, but also on their symbolic dimension. The fuzziness of ‘mega’ and ‘failure’ is part of the answer: ‘mega’ refers to the big promises that underpin large-scale projects, pointing to the politics of aspiration as a driver of investment and change. ‘Failure’ must be understood not in absolute terms, as a total collapse, but rather as a relative category in which achievements are compared to the originally declared goals. Megaprojects are always ambiguous: they often do not deliver as planned, they may be misused for various purposes, but at the same time, they serve as tools of future making, as iconic landmarks of transformation, and as ‘beacons of hope’ (Fig. 1).

Notes

Government of Kenya (1965), Sessional Paper No 10.

LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority n.d.

Peralta, Eyder (2018). ‘A new Chinese-funded railway in Kenya sparks debt-trap fears’. 8 October. See https://www.npr.org/2018/10/08/641625157/a-new-chinese-funded-railway-in-kenya-sparks-debt-trap-fears. Accessed 2nd November, 2019.

Ibid.

Dominic Omondi (2019). Kenya debt to China hits Sh650b as SGR takes up more funds. The Standard, 31 August. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/business/article/2001340176/kenya-debt-to-china-hits-sh650b-as-sgr-takes-up-more-funds Accessed 2 November, 2019.

Olingo, Allan (2019) ‘Kenya fails to secure $3.6b from China for third phase of SGR line to Kisumu’ The EastAfrican, 27 April. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/kenya-fails-to-secure-3-6b-from-china-for-third-phase-of-sgr-line-to-kisumu-1416820 Accessed 29 July, 2020.

Muthoni (2020) Government illegally hired a Chinese firm to build SGR, court declares. The Standard, 20 June. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001375723/court-declares-sgr-deal-illegal Accessed 7 July, 2020.

World Bank (2020) Rapid Assessment of Crime and Violence in Narok County (Washington DC: World Bank).

The Star (2019a, 2019b, 2019c) Sit for Naivasha Dry Port Finally Identified, 18 April. https://www.the-star.co.ke/business/2019-04-18-site-for-naivasha-dry-port-finally-identified/ Accessed 2 November, 2019.

Ahmed and Cece (2019) Uproar in Coast over SGR leaves Governor Joho at a crossroads, Sunday Nation, 29 September, p. 22.

Njagih and Chepkwony (2019) State stops SGR policy after talks with leaders. The Standard, October 4. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001344289/we-got-a-deal-on-sgr-coast-leaders-say

Kitimo (2020) Uganda backs out of compulsory use of container port in Naivasha. The EastAfrican, 30 May. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/uganda-backs-out-of-compulsory-use-of-container-port-in-naivasha-1442320. Accessed 29 July 2020.

World Bank (2020) Crime and Violence Rapid Assessment in Narok County (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Murage, George and Martin Mwita (2019) Sh150Bn Nairobi-Naivasha SGR complete, Uhuru to launch, 15 October. https://www.the-star.co.ke/business/2019-10-15-sh150bn-nairobi-naivasha-sgr-complete-uhuru-to-launch/ Accessed 2 November, 2019.

Interview, Maasaielder, Suswa, 19 October, 2019.

World Bank (2020) Crime and Violence Rapid Assessment in Narok County (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Interview, Maasai elder, Suswa, 19 October, 2019.

Marete (2019) Isiolo Airport Mostly Idle after 2.7bn Upgrade. Business Daily, 7 May. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/shipping/Isiolo-Airport-mostly-idle-despite-Sh2-7bn-upgrade/4003122-5104960-mwawtm/index.html. Accessed 2 November, 2019.

Isiolo County Council (2004) The report of the sub-committee of the council appointed to look into the resettling of people affected by the expansion of Isiolo Airstrip. 10 December.

FGD with 14 Chiefs from Isiolo town, Isiolo town 9 May, 2017.

Mkutu and Abdullahi Boru (2019) Rapid Assessment of the Institutional Architecture for Conflict Mitigation. (Washington D.C. World Bank).

Interview, Vision 2030 official, Nairobi, 15 February 2019.

Kenya News Agency (2019) Farmers to benefit from private investment once the modern slaughter house is operational. 19 July http://www.kenyanews.go.ke/farmers-to-benefit-from-private-investment-once-the-modern-slaughter-house-is-operational/ Accessed 2 November, 2019.

Interview, official from Ministry of Livestock and Agriculture, Isiolo Town, 9 May, 2017.

The NIB recently changed its name to the ‘National Irrigation Authority’ (NIA) following the enactment of the Irrigation Bill (2020).

Dubbed the Big 4, Agenda 4 represents the government’s four main pillars of development, at the top of which is food security.

ADC farms are public lands set aside for agricultural development in most parts of Kenya since the 1960s. Progressively, however, these large tracts of land became victim to massive land grabbing, mostly by political and business elites.

Brendon Cannon (2019) ‘Unique Challenges face the Galana-Kulalu Irrigation Scheme’, Kenya Engineer, 17.10.2019, https://www.kenyaengineer.co.ke/unique-challenges-face-the-galana-kulalu-irrigation-scheme/

Capital New, 21.05.2019, ‘Senators’ shock at Sh580mn to clear bush for Galana-Kulalu project’, https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/news/2019/05/senators-shock-at-sh580mn-to-clear-bush-for-galana-kulalu-project/

The Star, 16.03.2019, ‘Coast region mourns the death of Galana Kulalu’, https://www.the-star.co.ke/siasa/2019-03-16-coast-region-mourns-the-death-of-galana-kulalu/

Daily Nation (15.09.2019) A sad envoy, pitiless maize cartels and Israel’s first failure. https://www.nation.co.ke/oped/opinion/A-sad-envoy--pitiless-maize-cartels/440808-5273496-eu9imtz/index.html.

The Star (21.03.2019) White Elephant: Hungry Turkanas protest failed KVDA food project. https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/rift-valley/2019-03-21-hungry-turkanas-protest-failed-kvda-food-project/.

The Coast (13.04.2019) TARDA avails Sh70 m to revive the Tana Delta Irrigation Schemes. http://thecoast.co.ke/2019/04/13/tarda-avails-sh70-m-to-revive-the-tana-delta-irrigation-schemes/03/23/agriculture/thecoast/492/17/.

References

Aalders, T. 2020. Ghostlines. Movements, Anticipations, and Drawings of the LAPSSET Development Corridor in Kenya. PhD dissertation, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg.

Ahmed, M & Cece, S 2019. Uproar in Coast over SGR leaves Governor Joho at a crossroads. Sunday Nation, 29 September, p. 22.

Ansar, A., B. Flyvbjerg, A. Budzier, and D. Lunn. 2017. Big is fragile: An attempt at Theorizing Scale. In The Oxford handbook of megaproject management, ed. B. Flyvbjerg, 60–95. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Appadurai, A. 2013. The future as cultural fact. Verso, London: Essays on the Global Condition.

Atieno, E. 2019. The implications of large-scale infrastructure projects to the communities in Isiolo County: The case of the LAPSSET corridor. MA thesis, US International University-Africa.

Ballard, R., and M. Rubin. 2017. A “Marshall Plan” for human settlements: How megaprojects became South Africa’s housing policy. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 95: 1–31.

Ballard, R. 2017. Prefix as policy: megaprojects as South Africa’s big idea for human settlements. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 95: 1–18.

Bazin, F., I. Hathie, J. Skinner, and J. Koundouno. 2017. Irrigation, food security and poverty – Lessons from three large dams in West Africa, International Institute for Environment and Development, London. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: UK & The International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Beckert, J. 2016. Imagined futures: Fictional expectations and capitalist dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bergius, M., T.A. Benjaminsen, F. Maganga, and H. Buhaug. 2020. Green economy, degradation narratives, and land-use conflicts in Tanzania. World Development. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104850.

Bradshaw, Y. 1990. Perpetuating underdevelopment in Kenya: The link between agriculture, class, and state. African Studies Review 33 (1): 1–28.

Browne, A.J. 2015. LAPSSET: The history and politics of an Eastern African megaproject. London: Rift Valley Institute.

Cannon, B. 2019. Unique Challenges face the Galana-Kulalu Irrigation Scheme. Kenya Engineer, 17 October. https://www.kenyaengineer.co.ke/unique-challenges-face-the-galana-kulalu-irrigation-scheme/.

Carmody, P. 2011. The New Scramble for Africa. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Chambers, R. 1969. Settlement schemes in tropical Africa: A study of organizations and development. London: Routledge.

Chen, H. 2016. China’s ‘one belt, one road’ initiative and its implications for Sino-African investment relations. Transnational Corporations Review 8 (3): 178–182.

Chome, N. 2020. Local transformations of LAPSSET Evidence from Lamu, Kenya. In Land investment & politics: Reconfiguring Eastern Africa´s Pastoral Drylands eds. Lind, J., Okenwa, D., and Scoones, E., 33–42. James Currey.

Chome, N., E. Gonçalves, I. Scoones, and E. Sulle. 2020. ‘Demonstration fields’, anticipation, and contestation: Agrarian change and the political economy of development corridors in Eastern Africa. Journal of Eastern African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2020.1743067.

Daily Nation 2019, 'A sad envoy, pitiless maize cartels and Israel’s first failure', Daily Nation, 15 September, <https://www.nation.co.ke/oped/opinion/A-sad-envoy--pitiless-maize-cartels/440808-5273496-eu9imtz/index.html>.

Dannenberg, P., J. Revilla Diez, and D. Schiller. 2018. Spaces for integration or a divide? New-generation growth corridors and their integration in global value chains in the Global South. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie 62 (2): 135–151.

Dye, B. 2019. Dam building by the illiberal modernisers: Ideology and changing rationales in Rwanda and Tanzania. In: SSRN Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3351344.

Elliot, H. 2016. Planning, Property and plots at the gateway to Kenya’s new frontier. Journal of Eastern African Studies 10 (3): 511–529.

Enns, C., and B. Bersaglio. 2019. On the coloniality of “new” mega-infrastructure projects in East Africa. Antipode 52 (1): 101–123.

Enns, C., and B. Bersaglio. 2020. Negotiating pipeline projects and reterritorializing land through rural resistance in Northern Kenya. In Social movements contesting natural resource development, ed. J.F. Devlin, 42–59. New York: Routledge, Abingdon.

Enns, C. 2017. Infrastructure projects and rural politics in northern Kenya: the use of divergent expertise to negotiate the terms of land deals for transport infrastructure. The Journal of Peasant Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1377185.

Enns, C. 2019. Infrastructure projects and rural politics in northern Kenya: The use of divergent expertise to negotiate the terms of land deals for transport infrastructure. The Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (2): 358–376.

Flyvbjerg, B., N. Bruzelius, and W. Rothengatter. 2003. Megaprojects and risk. An anatomy of ambition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Government of Kenya. 1965. African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya, Sessional Paper No. 10, Government of Kenya, Nairobi.

Government of Kenya. 2012. National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Northern Kenya and other Arid Lands, Sessional Paper No. 8, Government of Kenya, Nairobi.

Graham, S., and S. Marvin. 2001. Splintering urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. New York: Routledge.

Greiner, C. 2016. Land-use change, territorial restructuring, and economies of anticipation in dryland Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies 10 (3): 530–547.

Hannan, S., and C. Sutherland. 2014. Mega-projects and sustainability in Durban, South Africa: Convergent or divergent agendas? Habitat International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.02.002.

Harvey, P., and H. Knox. 2012. The enchantments of infrastructure. Mobilities 7 (4): 521–536.

Isiolo County Council. 2004. The report of the sub-committee of the council appointed to look into the resettling of people affected by the expansion of Isiolo Airstrip. Isiolo, Kenya: Isiolo County Council.

Jasanoff, S., and S.-H. Kim. 2015. Dreamscapes of modernity: Sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jedwab, R., E. Kerby, and A. Merabi. 2015. History, path dependence and development: Evidence from colonial railways, settlers and cities in Kenya. The Economic Journal 127 (603): 1467–1494.

Kanyinga, K. 2009. The legacy of the white highlands: Land rights, ethnicity and the post-2007 election violence in Kenya. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 27 (3): 325–344.

Kenya News Agency. 2019. Farmers to benefit from private investment once the modern slaughter house is operational. Kenya News Agency, 19 July. Accessed 2 November 2019. http://www.kenyanews.go.ke/farmers-to-benefit-from-private-investment-once-the-modern-slaughter-house-is-operational/.

Kitimo, A. 2020. Uganda backs out of compulsory use of container port in Naivasha. The EastAfrican, 30 May. Accessed 29 July 2020. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/uganda-backs-out-of-compulsory-use-of-container-port-in-naivasha-1442320.

LCDA. n.d. LAPSSET, LAPSSET corridor development authority. Accessed 01 February 2021. https://www.lapsset.go.ke/

Leo, C. 1981. Who benefits from the million-acre scheme? Toward a class analysis of Kenya’s transition to independence. Canadian Journal of African Studies 15 (2): 201–222.

Leshore, L., and D. Minja. 2019. Factors affecting implementation of vision 2030 flagship projects in Kenya: A case of the Galana-Kulalu irrigation scheme. International Academic Journal of Law and Society 1 (2): 395–410.

Li, T.M. 2005. Beyond “the state” and failed schemes. American Anthropologist 107 (3): 383–394.

Lind, J, Okenwa, D & Scoones, I. 2020. Land investment & politics. Reconfiguring Eastern Africa´s pastoral drylands. James Currey.

Marete, G. 2019. Isiolo airport mostly idle after 2.7bn upgrade. Business Daily, 7 May. Accessed 2 November 2019. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/shipping/Isiolo-Airport-mostly-idle-despite-Sh2-7bn-upgrade/4003122-5104960-mwawtm/index.html.

Mkutu, K., and Boru, A. 2019. Rapid assessment of the institutional architecture for conflict mitigation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Mkutu, K., T. Mkutu, M. Marani, and A.E. Lokwang. 2019. New oil developments in a remote area: Environmental justice and participation in Turkana. Journal of Environmental Development 28 (3): 223–252.

Mosley, J., and E.E. Watson. 2016. Frontier transformations: development visions, spaces and processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies 10 (3): 452–475.

Muema, M.F., P.G. Home, and J.M. Raude. 2018. Application of benchmarking and principal component analysis in measuring performance of public irrigation schemes in Kenya. Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture8100162.

Müller-Mahn, D. 2020. Envisioning African futures: Development corridors as dreamscapes of modernity. Geoforum 115: 156–159.

Murage, G., and Mwita, M. 2019. Sh150Bn Nairobi-Naivasha SGR complete, Uhuru to launch. The Star, 15 October. Accessed 2 November 2019. https://www.the-star.co.ke/business/2019-10-15-sh150bn-nairobi-naivasha-sgr-complete-uhuru-to-launch/.

Muthoni, K. 2020. Government illegally hired a Chinese firm to build SGR, court declares. The Standard, 20 June, Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001375723/court-declares-sgr-deal-illegal.

National Irrigation Authority (NIA). 2020. Galana Kulalu irrigation development project. National Irrigation Authority. Accessed 28 January 2021. https://irrigation.go.ke/index.php/projects/flagship-projects/galana.

Ngigi, S. 2002. Review of irrigation development in Kenya. In The changing face of irrigation in Kenya: Opportunities for anticipating change in eastern and southern Africa, eds. Blank, H.G., Mutero, C.M., and Murray-Rust, H. Colombo: International Water Management Institute.

NIB. 2015. Environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) report for the model farm in Galana-Kulalu. Nairobi: Government of Kenya.

Njagih, M., and Chepkwony, M. 2019. State stops SGR policy after talks with leaders. The Standard, October 4. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001344289/we-got-a-deal-on-sgr-coast-leaders-say.

Olingo, A. 2019. Kenya fails to secure $3.6b from China for third phase of SGR line to Kisumu. The EastAfrican, 27 April. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/kenya-fails-to-secure-3-6b-from-china-for-third-phase-of-sgr-line-to-kisumu-1416820. Accessed 29 July 2020.

Omondi, D. 2019. Kenya debt to China hits Sh650b as SGR takes up more funds. The Standard, 31 August. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/business/article/2001340176/kenya-debt-to-china-hits-sh650b-as-sgr-takes-up-more-funds. Accessed 2 November 2019.

Otieno, S. 2016. Agricultural investments: The new frontier of human rights abuse and the place of development agencies. Journal of Food Law and Policy 12: 141–162.

Peralta, E. 2018. A new Chinese-funded railway in Kenya sparks debt-trap fears. NPR, 8 October. https://www.npr.org/2018/10/08/641625157/a-new-chinese-funded-railway-in-kenya-sparks-debt-trap-fears. Accessed 2 November 2019.

Salet, W., L. Bertolini, and M. Giezen. 2013. Complexity and uncertainty: Problem or asset in decision making of mega infrastructure projects? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (6): 1984–2000.

Schindler, S., S. Fadaee, and D. Brockington. 2019. ’Contemporary megaprojects. An Introduction. Environment and Society: Advances in Research 10: 1–8.

Scott, J.C. 1998. Seeing like a state. How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

Sobják, A. 2018. Corruption risks in infrastructure investments in Sub-Saharan Africa. OECD Anti-Corruption and Integrity Forum. https://www.oecd.org/corruption/integrity-forum/academic-papers/Sobjak.pdf

Stepputat, F., and T. Hagmann. 2019. Politics of circulation: The makings of the Berbera corridor in Somali East Africa. EPD Society and Space 37 (5): 794–813.

Stetson, G. 2012. Oil politics and indigenous resistance in the Peruvian Amazon: The rhetoric of modernity against the reality of coloniality. Journal of Environment & Development 21: 76–97.

The Coast. 2019. TARDA avails Sh70 m to revive the Tana Delta Irrigation Schemes. The Coast, 13 April. http://thecoast.co.ke/2019/04/13/tarda-avails-sh70-m-to-revive-the-tana-delta-irrigation-schemes/03/23/agriculture/thecoast/492/17/.

The Star. 2019a. Sit for Naivasha dry port finally identified. The Star, 18 April. https://www.the-star.co.ke/business/2019-04-18-site-for-naivasha-dry-port-finally-identified/. Accessed 2 November 2019.

The Star. 2019b. Coast region mourns the death of Galana Kulalu. The Star, 16 March. https://www.the-star.co.ke/siasa/2019-03-16-coast-region-mourns-the-death-of-galana-kulalu/.

The Star. 2019c. White Elephant: Hungry Turkanas protest failed KVDA food project. The Star, 21 March. https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/rift-valley/2019-03-21-hungry-turkanas-protest-failed-kvda-food-project/.

Van der Westhuizen, J. 2007. Glitz, glamour and the Gautrain: Mega-projects as political symbols. Politikon 34 (3): 333–351.

World Bank. 2020. Rapid assessment of crime and violence in Narok County, World Bank, Washington DC.

Zelezer, T. 1991. Economic policy and performance in Kenya since independence. Transafrican Journal of History 20: 35–76.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers of this article, and to DFG for funding the collaborative research center “Future Rural Africa”.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller-Mahn, D., Mkutu, K. & Kioko, E. Megaprojects—mega failures? The politics of aspiration and the transformation of rural Kenya. Eur J Dev Res 33, 1069–1090 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00397-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00397-x