Abstract

This paper investigates household seasonal food expenditure inequality in the rural Lake Naivasha Basin, Kenya using the extended decomposition of Gini and primary data referred from February 2018 to January 2019. The new elements introduced by the paper are the disaggregation of the food expenditure by source of access (purchase, auto-consumption, and gifts); inclusion of traditional species in the food categories; the features of the area investigated; a novel focus on household economic disparities in flower enclave; and the comparison between the annual and monthly level of inequality to understand the seasonality in household inequality. The results highlight the positive contribution of the subsistence sector to the reduction of inequality during the harvesting period of respective food category; and the need for a well-coordinated set of poverty, food security and agricultural development policies to contribute to the achievement of the first goal of Agenda 2030.

Resume

Cet article analyse les inégalités dans les dépenses alimentaires saisonnières des ménages au bassin rurale du Lac Naivasha au Kenya, utilisant une décomposition étendue de données Gini et de données primaires soumises entre Février 2018 et Janvier 2019. Cet article introduit des nouveaux éléments, notamment : la désagrégation des dépenses alimentaires selon leur source d’accès (achat, autoconsommation, cadeau) ; l’inclusion d’espèces traditionnelles dans les catégories alimentaires ; les caractéristiques de la zone étudiée ; plus d’attention prêtée aux disparités économiques entre les ménages dans la zone où se trouve l’enclave dédié à la cultivation de fleures ; et la comparaison entre les niveaux d’inégalité annuels et mensuels, afin de comprendre la saisonnalité dans les inégalités des ménages. Les résultats soulignent la contribution positive du secteur de subsistance à la réduction de l’inégalité pendant les périodes de la récolte ; et la nécessite de politiques qui coordonnent les interventions en matière de pauvreté, sécurité alimentaire, et développement agricole afin d’atteindre le premier objectif de l’Agenda 2030.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Following the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals in September 2015 and their core principle of leaving no one behind, the attention on inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa has gained substantial attention (Odusola 2017). Income disparity is one of the areas of concern. The benefits of an acceleration in economic growth remain unevenly distributed, and Sub-Saharan Africa is still one of the most unequal regions in the world (Cogneau et al. 2007; Okojie and Shimeles 2006; Van de Walle 2009; Go et al. 2007).

In this context, rural areas deserve specific attention due to the high incidence of poverty and unequal development (Dercon 2009; World Bank 2013), which is undermining the advantages from technological progress including those in agriculture (Go et al. 2007). Research on income inequality in Africa has developed only recently with the availability of household budget surveys. Assessments of income inequality at the national or regional level are now available for all the African countries. The majority of the literature refers to the Gini index to measure the inequality and distinguishes between urban and rural areas. Moreover, due to data availability, these studies primarily use expenditure as a proxy for income (Ferreira and Ravallion 2009). However, as indicated by Lazaridis (2000), one of the problems associated with the use of total expenditure is that households may declare zero expenditure of a certain item only because they have not purchased the specific good or services during the survey recall period. The possible case in point is household expenditure on education, which might occur only during the school period, or the life-long durable goods that are purchased only occasionally. For this reason, the literature considers the distribution of total expenditure on food as an acceptable proxy for income despite its limitations. Following the decomposition of the extended Gini coefficient introduced by Lerman and Yitzhaki (1985), this body of the literature also investigates the contribution of the different food items to overall food expenditure inequality. The distribution of food expenditure patterns also represents a critical aspect of the evaluation of food policy issues.

While calculating the food consumption expenditure as a proxy for household income, along with the main food groups specified by the FAO, our study also includes the traditional species among the food categories. The traditional species have an important role in food and nutrition security (Muthoni and Nyamongo 2010), and the Government of Kenya has a specific policy focus on the increase of their production for food availability, food accessibility, and nutrition improvement (Republic of Kenya 2011, 2013, 2016).

There are various sources from where the household can access different food items. The literature typically emphasizes the food consumption expenditure for items purchased from the market. However, none of these studies captures the specificities of the household food sources in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the region, household access to food is through three different sources, i.e. the market, own production, and transfers from public programmes or other households. Despite some studies indicating a change in household consumption in Africa towards a dependence on the market (Bricas et al. 2016), subsistence production remains an important component in total food consumption, especially for poor households. A study by Chauvin et al. (2012), based on a sample of 19 Sub-Saharan countries, shows that the auto-consumption of the households in the first income quintile is on average 35%; this incidence decreases to an average of 22% for the households in the last quintile. Similarly, food transfers represent an important source of earnings, especially for poor households and, therefore, in the distribution of income and wealth.

The distinction among typologies of household food access sources in income inequality analysis is of specific importance from the policy point of view. In fact, each of these components reacts to a specific set of policies introduced to reduce food expenditure inequality. For example, taxes or subsidies can reduce inequality through their application on food purchased while agricultural policies affect production in the subsistence sector to improve the auto-consumption. The issue is even more complex when the direction of the effect of the components on income inequality is different. For this reason, studies on inequality require incorporating these aspects based on a detailed data collection in order to define even more effective and robust growth strategies. On the contrary, the available secondary data does not provide the appropriate information to address the issue.

Our paper covers this gap in the literature taking advantage of a rare dataset that we constructed to assess food insecurity in the rural lower and middle catchment of the Lake Naivasha basin. Based on the extended decomposition of Gini, we provide an analysis of food consumption inequality of a representative sample of households distinguished in terms of food category and access typology, i.e. food purchased in the market, auto-consumed, and given as a gift. In order to capture these aspects, we collected primary data for each month from February 2018 to January 2019 for a statistically representative sample of 601 households.

The final new element covered by our study is to highlight the seasonal fluctuation in food expenditure inequality among rural households in Naivasha Basin. In rural Kenya, almost 80% of the population works as a small farmer producing predominantly for subsistence using rainfed agriculture. They usually harvest once in a year and are highly vulnerable to weather-related shocks (droughts and floods) and climatic conditions (WFP 2016). Therefore, food production in rural Kenya faces seasonal variation that affects food availability and consumption inequality.

Our study has collected monthly data on food consumption expenditure on different items rather than relying on the conventional annual level data to capture the seasonal food expenditure inequality. Though the seasonal variation in food expenditure inequality is a well-admitted fact in the literature, most of the existing studies on the Gini coefficient decomposition of the food expenditure inequality has mainly used annual data for their analysis (Bose and Dey 2007; Lazaridis 2000). Our paper has compared the results using both the annual and monthly data, which provides numerous advantages, among which enabling the better targeting period of the inequality reduction policies is the most important one to mention.

The recent Human Development Report by UNDP (2019) propounds that the measurement of inequality should go beyond income, averages, and today. In line with that, our paper has considered food consumption expenditure from different access sources instead of income, and monthly data instead of using average annual values. The understanding of the seasonal food expenditure inequality in the rural areas around Lake Naivasha is an interesting case because a flower enclave is shaping its economic development. The dominating large flower sector coexists with a system of smallholder farms (Ghawana 2008). According to the literature, the floriculture industry creates job opportunities that smallholder farmers consider as a way to diversify their livelihood (Agustina 2008). The scant literature on floriculture refers to the farming system perspective addressing issues such as land acquisition and competition, business model, and employment generation. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet verified the state of seasonal income inequality in these areas.

The paper is organized as follows: next section presents the dataset used in the paper and the data collection procedure, followed by the subsequent two sections dedicated to the description of the empirical strategy, and the presentation and discussion of the empirical results. The last section concludes.

Data

The dataset used in this paper refers to a longitudinal survey, structured in accordance with the theoretical framework of Sassi (2012, 2015, 2018) and developed following the Cochran (1997) steps, aimed at collecting information on poverty and food insecurity in the lower and middle basin of Lake Naivasha. Our longitudinal survey, conducted from February 2018 to January 2019, is the first comprehensive survey that not only tracks the household consumption expenditure over time but also allows us to capture the seasonal pattern of such expenditure in our research area.

We dedicated specific attention to the sample selection. We used the clusters adopted by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. We selected them according to the master frame known as the fifth National Sample Survey and Evaluation Program that was developed in 2012 to conduct household budget surveys (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics 2014). According to this sampling method, Nakuru County has 149 clusters, further sub-divided into rural and urban. We selected the households as statistically representative of the seven rural clusters in the lower and middle catchment basin of the Lake Naivasha in the sub-counties of Gilgil and Naivasha.

With the support of the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, we selected 601 households from a total population of 28,939 households using the Cochran’s formula (1997). We used a 5% probability of error and the desired margin of error of 4%. According to this formula, our sample size should include 588 households. However, we considered a larger sample to avoid its possible reduction below the representative level due to missing values or possible mistakes in data collection.

We used the data collected in the section ‘Food Basket’ of the questionnaire, and we classified the 80 food items that it provides into the following seven categories: ‘Maize’, ‘Rice’, ‘Other cereals’, ‘Tubers’, ‘Vegetables and fruits’, ‘Animal and vegetable proteins’, and ‘Traditional species’. We selected food categories based on their relative nutritional importance as well as on their relative share in relation to the total consumption expenditure. Concerning the ‘traditional species’, we noted that there is no official definition and common understanding of the term in the investigated area. According to some households, traditional species are foods associated with a certain tribe or community, and the majority of them are staple foods. Others suggest that the term ‘traditional species’ in some instances is a misnomer. In most cases, it refers to indigenous species that are mostly undomesticated and could, therefore, be foraged. Over time, most of these species' germplasm are harnessed and multiplied to the extent that the seeds can be bought and planted. Even under such circumstances, the vegetables retain the tag ‘traditional vegetables’ since they preserve their original characteristics and require very little (if any) complex agronomic husbandry. Some other traditional vegetables remain as ‘wild vegetables’ and only spontaneously sprout when it rains. We decided to consider those crops as ‘traditional species’ that respondents identified with in accordance with this latter denomination during the survey.

The section ‘Food Basket’ of our questionnaire provides the quantities of food items purchased from the market, auto-consumed, and received as a gift, and their corresponding unit price.

In our survey, ‘gifts’ is a category that includes the food items given or offered to the respondent as opposed to those purchased, exchanged (barter) or produced.

We computed the monetary value of the food items purchased from the market multiplying the quantity by the unit price. For the food auto-consumed and received as a gift, we used the unit price paid by the household to purchase the same category of food from the market. In a very limited number of cases, this information was not available. In order to overcome the problem, we used the median unit price of the food item computed over the whole sample of households. To control for the effect of inflation on the prices of food items, we divided all the prices in each respective month by consumer price index (CPI) as obtained from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

We controlled for differences in consumption across households due to different household sizes or composition by transforming the household-level consumption into the individual consumption based on an equivalence scale (Deaton and Muellbauer 1980). More precisely, we transformed the food expenditure by item in adult equivalent terms using the following OECD (1982) scale: 1 for the first adult, 0.7 for any other adult member, 0.5 for each household members below 15 years old, i.e. those not in the labor force according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (Haughton and Shahidur 2009). This criterion assumes the same basic needs for all the household members, and therefore, is an approximate measure of individual welfare.

At the end of the twelve-month survey, we conducted seven focus group discussions, one in each cluster, to gain an in‐depth understanding of the investigated phenomena. Each focus group comprised of eight members, purposively selected among the respondents to the questionnaire survey while also ensuring the gender balance of elderly and adult participants. The purposive selection of the participants was based on the respondents’ capacity to provide relevant information as verified during the questionnaire survey by the enumerators. In each group, a trained facilitator guided the discussion based on a set of predefined key questions designed around the most important research objectives of the study. We devoted special care in creating a non-threatening environment for participants to share their responses freely and openly.

Empirical Strategy

In this paper, we studied income inequality and the role of the different sources of household access to food using the decomposition of the extended Gini coefficient proposed by Lerman and Yitzhaki (1985) following the work of Stuart (1954). In the work of Lerman and Yitzhaki (1985) the standard Gini coefficient takes the following form,

where \(y\) is the household total food expenditure, F(y) its cumulative distribution, \(\overline{y}\) its arithmetic mean.

We have further captured the seasonal pattern of income inequality and its decomposition by incorporating a time dimension in our analysis as:

where t denotes the month of the year ranging from February (month 1) to January (month 12).

Using the properties of the covariance and denoting the ith food expenditure component at time t by \(y_{it}\), this formula can be rewritten as

Multiplying and dividing each component in Eq. (3) by \(cov\left[ {y_{it} ,F\left( {y_{t} } \right)} \right]\) and \(\overline{y}_{it}\) yields

where \(R_{it} G_{it} S_{it}\) is the inequality contribution to overall Gini index from food expenditure it time t, if this expenditure were the only source of income differences.

Following Stark et al. (1986), \(R_{it}\) in Eq. (4) is the Gini correlation coefficient representing the inequality resulting from the correlation coefficient between the food expenditure of a given category (\(y_{it} )\) and the distribution of total household fooexpenditure (\(y_{t}\)) at time t. It is given by

A negative sign of \(R_{it}\) implies an income distribution unbalanced towards the poorest individual and vice versa. The element \(G_{it}\) is the Gini coefficient for the food expenditure \(y_{it} {\text{at time }}t\). It is of the form

This component explains whether the expenditure for a given category of food is distributed equally or unequally. Zero represents absolute equality and one absolute inequality.

Finally, \(S_{it}\) is the share of \(y_{it}\) in total food expenditure at time t. It is given by

This component informs on the significance of the expenditure for an ith category of food in relation to total food expenditure at time t.

If an ith food expenditure category is a large share of total food expenditure, wmight also expect to have its large impact on total inequality. We can verify this possibility using the contribution from the ith food expenditure component to overall inequality at time t, which is given by

From this equation, it is easy to note that the impact of the ith food expenditure on total inequality depends on the value of its components. As explained in Eid and Aguirre (2013) and Sing (2015), if \(G_{it}\) is equal to 0, i.e., food expenditure in the ith category is equally distributed, then it cannot affect inequality even in the case of a high value of \(S_{it}\). If the \(S_{it}\) and \(G_{it}\) are large (an important source of expenditure unequally distributed), the source of food expenditure will positively contribute to inequality if \(R_{it}\) is positive and large, i.e., the expenditure is disproportionate towards those at the top of the distribution.

Eation (4) allows us to estimate the impact of a small exogenous change in each household’s food expenditure category i at time t on overall inequality by a factor e, where e tends to 1. The exogenous change can be due to the introduction of a tax or a subsidy. The impact is given by

Dividing by the standard Gini coefficient, we obtain

According to this equation, the relative effect of a marginal percentage change in food expenditure category i at time t is given by the relative contribution of the food item i over total inequality (\(C_{it}\)) minus its relative contribution to total food expenditures (\(S_{it}\)). It should be noted that the overall Gini in each month (\(G_{t}\)) remains unchang if all food expenditure components are multiplied by e (Lerman and Yitzhaki 1985).

The sign of this marginal effect is important from a policy point of view. In fact, when it is positive (negative) a decrease in the expenditure on food item i will reduce (increase) inequality.

Since \(S_{it}\) and \(G_{it }\) are positive, the sign of the marginal effect depends on the sign of \(R_{it}\) and \(R_{it} G_{it} - G_{t}\). If the Gini correlation (\(R_{it} )\) is negative or zero, the marginal effect is negative. If \(R_{it}\) is positive, the sign of the marginal effect depends on that of \(R_{it} G_{it} - G_{t}\). It is positive, if \(R_{it} G_{it} > G_{t}\), and vice versa.

Changes in inequality have ambiguous implications for social welfare. As explained in Stark et al. (1986), ceteris paribus, a small increase in income of any member of the society may increase inequality. We added a time dimension to the social welfare function introduced by Yitzhaki (1982) and Stark and Yitzhaki (1982) as:

According to this function, an increase in income or a reduction of inequality improves social welfare, independent of the shape of the initial income distribution.

From this measure, we obtain the effect of a small change (e) in income from source i on welfare at time t as

Aexplained in Stark et al. (1986), Eq. (8) shows that the effect on welfare (\(W_{t}\)) at time t from a small percentage increase in income is the result of two components, an income effect (\(\overline{y}_{it}\)) and a distributional effect \(\overline{y}_{it} R_{it} G_{it}\). The sign of the former component is positive while that of the second depends on the sign of \(R_{it}\). However, the distributional effect is always lower than the income effect because \(R_{it}\) and \(G_{it}\) are ls than one. Therefore, the distributional effect can enhance or weaken the income effect.

Iour paper, we used the welfare effect formula in percentage terms defined as follows:

Equation (9) shows the percentage change in household welfare of a 1 percent increase in income from different food items at time t.

Following Yitzhaki (1990), we can use \(R_{it}\) and \(G_{it}\) to compute the Gini elasticity (\(E_{it}\)) of the aggregate earning for food item i at time t with respect to the aggregate food enings. It is given by

As shown by Yitzhaki (1990), this elasticity supports the Engel aggregation. According tthe value of \(E_{it}\), we can distinguish three typologies of food items: ‘luxury’ when the elasticity is greater than one, ‘necessities’ when it is between zero and one, and ‘inferior’ if it is negative. Therefore, the Gini elasticity complements the analysis on the impact of policy interventions on welfare.

Iral, following Malá and Červená (2012), if \(E_{it}\) is higher than 1, the ith category of food expenditure is inequality-increasing at time t in the sense that an addition increment of that source of income, distributed in the same manner as the original unit, contributes to the growth of total inequality. If it is lower than 1, the expenditure category is inequality-decreasing. If it is equal to 1, there is a neutral effect.

Results and Discussion

Gi Coefficient and Decomposition by Access Typologies

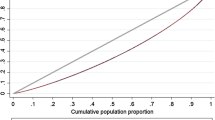

In this section, we present prevailing income inequalities in our research area, and its decomposition in terms of food access typologies referring to market purchase, auto-consumption, and gifts in each month during our study period (February 2018—January 2019). The relevance of longitudinal data on analysing inequalities is evident in Fig. 1. It shows that if the Gini index were calculated annually, as in the dominant literature, it would have disregarded the existing relevant seasonal variation of income inequality. More specifically, we observe that the annual Gini index underestimates the consumption inequality in the initial three months, in February, March, and April, when there is a sparse production of food crops. Afterwards, the annual level of inequality begins to show upward trends in May as opposed to what would have been observed on a monthly basis, thus, overestimating the household income inequality. The harvesting season of vegetables and cereals starts in May as suggested by Sassi (2019), and it is, thus, unsurprising that the level of inequality coincides with the seasonality of harvesting season for crops. This seasonal variation in consumption inequality calls for an analysis of its sources that might exhibit different patterns in different months over the year, and therefore, requiring specific policy solutions to ensure that the fluctuating levels of inequality in food consumption do not progress into chronic nutrition and food insecurity in the research area.

As discussed in the introduction, most of the studies on the consumption inequality focus only on food items purchased from the market, thus, ignoring other important typologies of food access, like auto-consumption (crops produced by households themselves) and gifts (food provided as gifts or as a part of food aid). However, Table 1 reveals that auto-consumption and gifts form a substantial proportion of total household food expenditure in our research area. Though market purchase is the dominant source of expenditure, on an average, auto-consumption comprises almost one-third of share in the total food expenditure, which is not negligible.

Figure 2 provides a graphical summary of the decomposition of the Gini index by access typology in each of the months during our study period. It highlights that inequality is highest when we consider only the purchased food consumption. However, if we aggregate both purchase and auto-consumption, the inequality decreases significantly. The inequality further shows an additional minor decrease if we add food gifts. Our observation indicates that if all the foods were only obtained through market purchases in contrast to other access typologies, the inequality would have been the highest. In contrast, the auto-consumption exerts the most positive role in bringing down the total inequality than what would have occurred if all the food were only purchased. The food gifts have a very limited equalizing role in reducing the total inequality in comparison to the auto-consumption. Consequently, our analysis provides clear evidence on the highest potential of own production in reducing income inequality.

The rationale behind the prominent equalizing role of own production can be understood from Fig. 3. It highlights that the consumption inequality within auto-consumption is higher than among those purchased. This result might appear to be contradictory to the previous result on the positive contribution of auto-consumption in lowering the total inequality. However, auto-consumption has a lower Gini Correlation (on an average 0.52) in relation to the total consumption inequality suggesting its disproportionate share towards the poor, which, therefore, counteracts the higher inequality within the purchased consumption (on an average 0.65) for poor. The literature also supports this unbalanced concentration of consumption of own-produced foods, as the poor smallholders are more involved in subsistence farming to producing their food in Kenya (FAO 2015).

We also observe that gift is the most unequally distributed source of food among households. However, the share of gifts on total household consumption expenditure is very low (on an average of 6.07%), and its contribution to consumption inequality is very minimal (on an average of 7.74), which constraints its equalizing role. Moreover, gifts are not entirely concentrated towards the poor section. As explained during the focus group discussions, the transfer of gifts in kind to the poor is uncommon except where churches and humanitarian organizations are involved. The culture in the investigated area dictates that whenever individual purposes to visit another (either a relative or friend), this person carries a 'gift' for the visited household. Usually, the visitor may most likely bring a gift that is not in season, or is rare or is an item that distinguishes the recipient as someone held in high esteem, implying that the prices of these gifted items would be higher. Depending on the social and power structure, we also noted that this cultural norm is mostly applied by poor people visiting the richer folks in seeking some form of favour, such as job opportunities or inviting the rich to be a guest-of-honour in a special event. Given the importance of auto-consumption in reducing inequality, our study suggests a stronger policy focus on the promotion of productivity of the agriculture sector rather than solely improving the market mechanisms.

Gini Decomposition by Food Categories

In the previous section, we highlighted the equalizing role of auto-consumption in reducing consumption inequality. However, the importance of this equalizing role might vary for different food groups, more so due to the variation in the consumption pattern of these food categories in different months based on their respective harvesting season and food availability. Figure 4 shows this variation in the consumption pattern illustrating the average percentage share of total household consumption expenditure in each of the seven food categories during our study period. In the figure, we can observe that maize and rice are the most dominant food items consumed by the households throughout the year, and are, thus, staple cereals. On the contrary, the protein sources have the lowest share in the consumption expenditure, thus, indicating a very low level of protein in the dietary composition of households in all the months. More importantly, Fig. 4 also suggests a fluctuation in the household level dietary composition and diversity in different seasons. We can observe that the dietary composition is particularly more diverse after the harvesting season of Maize (after August) than during the season of long rains (March, April, and May) when households replace the consumption of vegetables and fruits with traditional species as the production of vegetables and fruits gets relatively low (Sassi 2019).

To further ascertain the seasonal pattern and the role of auto-consumption, we have further decomposed the total income inequality into its sources in terms of food access typologies in each of these seven food categories. The results of our decomposition analysis suggest three food groups based on the role of auto-consumption in reducing inequality. These considered food groups are 1) food categories for which auto-consumption contributes the most; 2) food categories for which the role of auto-consumption is inconsistent; and 3) food categories for which the role of auto-consumption is minimal.

Food Group for Which Auto-consumption Contributes the Most to Reduce Inequality

We found that the auto-consumption of maize, tubers, and traditional species contributes the most in reducing total inequality. Among these three food categories, Fig. 5a indicates that the auto-consumption of maize has the most significant equalizing role in reducing the total inequality especially after its harvesting season in August when the inequality within the purchased maize begins to rise sharply until the year-end. Moreover, our analysis reveals that unlike the purchased maize, the auto-consumption has a negative marginal effect, more so after the harvesting season. During that period, an increase in auto-consumption accentuates inequality towards the poor segment of the analyzed population, further reducing total inequality. In addition, the self-consumption of maize exhibits the highest welfare effect among all the own produced crops.

Furthermore, comparing the value of Gini correlation (\(R_{it}\)) and the marginal effect, we have found that the purchased maize is always an inequality increasing luxurious item, whereas, as previously noted, the auto-consumed maize is an inequality decreasing normal good, especially after the harvest season. Another food category, tuber, constitutes the second-highest expenditure share among the auto-consumed food after maize. As illustrated in Sassi (2019), the harvest period of tubers starts in May, and it is when the positive effect of auto-consumed tubers in reducing the total income inequality begins to get more pronounced (Fig. 5b). Similar to the maize, we found the auto-consumed tubers to be an inequality decreasing normal good, and also to exhibit a high welfare effect.

These results suggest the relevance of policies aimed at promoting smallholder farmers’ maize and tuber production for income inequality reduction. Therefore, there is a need to create synergies with the agricultural policy and those especially aimed at decreasing income inequality. This aspect is even more critical if we consider the fact that the Government of Kenya is sensitive to the development issue of poor farmers through maize and tuber production. The key issues of the National Agriculture Policy of Kenya are concentrated on increasing the efficiency of maize production for smallholder farmers and emphasizing on irrigation to reduce over-reliance on rain-fed agriculture in the limited high potential agricultural land (Alila and Atieno 2006). Moreover, in our research region Nakuru, USAID has intervened to increase the capacity of production and consumption of maize of the smallholders through Kenya Maize Development Program (KMDP) (USAID 2012). In the case of tubers, Kenya has more recently developed the National Root and Tuber Crops Development Strategy (2012–2019) to improve the production of roots and tubers, especially among the smallholders. The strategy mainly focuses on introducing drought and pests resistant improved seeds to tackle the seasonal fluctuation in the production of roots and tubers, and in improving the value chains among stakeholders (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation 2019).

Regarding the traditional species, we have found that households consume more of auto-consumed traditional crops than those purchased. This result is unsurprising due to an observation revealed during the focus group discussion that the households, particularly with lower income, collect wild foods that are available freely, especially during the long rainy season when vegetables and fruits are sparsely produced. The role of traditional species in reducing the total income inequality becomes more prominent during the early dry season (February and March) when the production of other food groups is limited. This inequality decreasing effect can be explained by the fact that traditional species are well-adapted to the climatic conditions of the study region, and hence, are immune to seasonal fluctuations. Consequently, traditional species form an important source of nutrition, especially for poor households in the dry season (Muthoni and Nyamongo 2010), thus, contributing to minimizing the gap in the consumption among rich and poor households.

Food Categories for Which the Role of Auto-consumption is Strongly Inconsistent

Among all the food categories, only animal and vegetable protein sources exhibit the inconsistent role of auto-consumption in equalizing the consumption inequality in the research area, as can be observed in Fig. 6. The figure highlights that the contribution of own production of animal and vegetable protein sources in reducing the overall inequality is particularly limited in the initial four months (February, March, April, May), but gradually increases in the subsequent months, and begins to narrow towards the year-end. This inconsistency is largely explained by the disproportionate concentration of protein sources among higher-income households with the Gini index close to 1, irrespective of food access typologies. We found that protein sources are inequality increasing luxurious food items and their inclusion in the dietary composition is minimal throughout the year. As a result, its auto-consumption exhibits a limited role in decreasing the overall inequality. Nonetheless, we observe a positive effect of its auto-consumption with the increased availability of vegetable protein sources after the harvesting season of beans in May, as beans constitute a major component of protein sources in our research area (Sassi 2019).

The Gini correlation of purchased vegetable and animal protein sources has very high value (on average, \(R_{it} = 0.764\)), indicating that the market accessibility of protein is mostly limited to richer households. Nonetheless, this group of food categories is very crucial in improving the nutritional adequacy of diet (de Bruyn et al. 2016), particularly given their limited consumption by poor households. Therefore, the income inequality interventions can be supported by the nutritional policies to ensure the access of nutritious protein items to poor households, which will result in a decrease in income inequality simultaneously.

Food Categories for Which the Role of Auto-consumption is Minimal

This group of food categories comprises of rice, other cereals, and vegetables and fruits, for which the auto-consumption contributes most minimally in reducing the total income inequality in our study area, as can be observed in Fig. 7a–c. In fact, on the contrary to the other two food categories, this category portrays a higher effect of gifts in reducing the consumption inequality than that of auto-consumption.

In regard to individual food categories, we have observed that the household consumption of rice is mostly obtained from the purchase in all the months, which limits the role of its auto-consumption in reducing inequality. The share of consumption expenditure in the purchased rice gets considerably higher after the harvesting season of maize when households’ purchasing power improves after the sale of produced maize. However, rice is an inequality increasing luxurious food item as its consumption, throughout the year, including the post-harvest period of maize, is particularly concentrated among the wealthier households. In Kenya, rice is the third most important cereal crop after maize and wheat. The demand for rice consumption is increasing more rapidly than its production at an average rate of 11% since 1960, thus, making Kenya predominantly a rice importing country (Ouma-Onyango 2014). Rice is grown mainly by small-scale farmers as a cash crop (Gitonga 2016), and thus, carries a strong potential to improve the food security and livelihoods of poor smallholder farmers. On the policy front, the Kenyan government has recently formulated the National Rice Development Strategy (NRDS) for the period 2008 – 2018 towards increasing the use of improved seeds, pests and disease control, and land quantity in irrigation schemes (Ministry of Agriculture of Republic of Kenya, n.d.). However, even with such measures for increasing the productive capacities of poor farmers, domestic rice production is still lagging in Kenya.

As captured in the ‘other cereals’ food group of our analysis, wheat is the important cereal in the diets of Kenyan households. However, similar to rice, Kenya’s domestic wheat production is also limited due to a low selling price and only meets less than one-quarter of its annual demand. Consequently, the domestic production of wheat is offset by imports (Gitonga 2016). As a result, it has a low share in auto-consumption and prevailing inequalities in consumption.

Finally, Fig. 7c suggests that the role of auto-consumption and gifts in decreasing inequality is minimal for the food category ‘vegetables and fruits’, throughout the year. In fact, we observe that the households are primarily dependent on market purchases for their consumption of vegetables and that such purchased consumption is disproportionately concentrated towards the wealthier households, thus, contributing to the increase in the total inequality. On the contrary, auto-consumed vegetables and fruits are found to be inequality decreasing normal food, however, exhibiting a very low share among the auto-consumed crops. Nevertheless, fruits and vegetables are an important source of micronutrients in the diet.

Conclusions

This paper examines the variation between annual and monthly income inequality in the rural lower and middle catchment of the Lake Naivasha basin using a dataset that allows distinguishing among food categories and access typology for each month of the year. Despite the flourishing floricultural sector in the investigated area, income inequality is still a problem, which is, in part, mitigated by food auto-consumption and gifts.

The paper mostly highlights the important role of production for self-consumption in reducing inequality, especially after the harvesting period of each food group. It emphasises the role played by different crops in different periods, and the effect of their specific seasonal calendar on the local production for smallholders. However, our paper contradicts the literature that considers the subsistence sector as an impediment to economic growth, at least at first. On the other side, it adds to the literature that recognizes subsistence agriculture as a way for rural people to survive under extremely difficult and risky conditions, and also as a way to reduce inequality. Furthermore, our analysis emphasizes the noteworthy link between seasonal inequality and the four pillars of food security (availability, access, utilization and stability of food). Policies need to take additional steps to study the best ways to improve the productive efficiency of the small farmers in the harvesting months when most of the food groups have the highest potential to reduce inequality.

Maize represents an interesting case. It is the most important staple food in Kenya, and for this reason, it is policy sensitive. Therefore, the support to production for self-consumption seems to be a more reasonable policy intervention than the imposition of tax, even if regressive, on its consumption price to reduce inequality. Moreover, the auto-consumption of maize has the highest welfare effect after its harvesting season. Though the National Agriculture Policy of Kenya and many programs are targeted to improve the production efficiency of maize by small farmers, there is still a need to intensify these efforts further, as strongly suggested by the evidence gathered by our analysis and due to the persistent levels of food consumption inequality.

The auto-consumption of another category that deserves specific attention is the traditional species. In the policy framework of the Government of Kenya, these species are important for increasing agro-biodiversity, for their nutritional content and to improve food affordability and availability (Republic of Kenya 2016). This food category is playing a very positive role in the consumption of poor households during the dry season. Therefore, Kenya has set an objective to increase the utilization of traditional species by 10 percent by 2020 and promote their production (Republic of Kenya 2016).

Among all the food groups, the contribution of the auto-consumption of rice and wheat is the least to decrease inequality as they are usually imported and their consumption is mostly derived from the market purchase in Kenya.

However, the demand for their consumption is increasing day by day, and therefore, they are gradually having a high share in households’ consumption expenditure. In this case, Kenya should utilize its potential of smallholders and arable land to improve the agricultural production of these highly demanded food items.

Our results also suggest that food utilization interventions may contribute to reducing inequality. An example is the need to promote a diet diversification among poor households towards higher protein food. Both the production and consumption of the vegetables, fruits and protein sources are very limited among all the access typologies. Besides the staple cereals, the policy and programs should also initiate and promote the programs focusing on the vegetable garden and livestock rearing. However, these considerations also highlight the need to understand the constraints that may inhibit small farmers’ production of higher protein food and introduce appropriate measures to deal with these possible constraints.

The empirical evidence calls for a strong integration among the targeting time of the policies and interventions aiming to reduce income inequality, to promote the agricultural development, and to ensure food and nutrition security for closing economic disparities among households in the investigated area.

Change history

29 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00394-0

References

Agustina, S.R. 2008. Land Use/Farming System and Livelihood Changes in the Upper Catchment of Lake Naivasha, Kenya. MSc Thesis, International Institute for Geo-Information Science And Earth Observation, Enschede, The Netherlands.

Alila, P.O., and R. Atieno. 2006. Agricultural policy in Kenya: Issues and processes. Nairobi: Institute for Development Studies, University of Nairobi.

Bose, M.L., and M.M. Dey. 2007. Food and nutritional security in Bangladesh: Going beyond carbohydrate counts. Agricultural Economics Research Review 20 (482): 203–225.

Bricas, N., C. Tchamda, and F. Mouton. 2016. L'Afrique à la conquête de son marché alimentaire intérieur. Enseignements de dix ans d’enquêtes auprès des ménages d’Afrique de l’Ouest, du Cameroun et du Tchad. Collection Études de l’AFD, AFD 12.

Cochran, W.G. 1997. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed. New York: Wiley.

Cogneau, D., T. Bossuroy, P.D. Vreyer, C. Guénard, V. Hiller, P. Leite, C. Torelli, and S. Mesplé-Somps. 2007. Inequalities and Equity in Africa. Paris: Agence Française de Développement - Research Department.

Colen, L., P.C. Melo, Y. Abdul-Salam, D. Roberts, S. Mary, Y. Gomez, and S. Paloma. 2018. Income elasticities for food, calories and nutrients across Africa: A meta-analysis. Food Policy 77: 116–132.

de Bruyn, J., E. Ferguson, M. Allman-Farinelli, I. Darnton-Hill, W. Maulaga, J. Msuya, and R. Alders. 2016. Food composition tables in resource-poor settings: Exploring current limitations and opportunities, with a focus on animal-source foods in sub-Saharan Africa. British Journal of Nutrition 116 (10): 1709–1719.

Deaton, A., and J. Muellbauer. 1980. Economics and Consumer Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Depetris Chauvin, N., F. Mulangu, and G. Porto. 2012. Food production and consumption trends in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prospects for the Transformation of the Agricultural Sector. UNDP Africa Policy Notes 2012-011.

Dercon, S. 2009. Rural poverty: Old challenges in new contexts. World Bank Research Observer 24 (1): 1–28.

Eid, A., and R. Aguirre. 2013. Trends in income and consumption inequality in Bolivia: A fairy tale of growing dwarfs and shrinking giants. The Latin American Journal of Economic Development 20: 75–110.

FAO. 2015. The economic lives of smallholder farmers. Fao 4 (4): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.5296/rae.v6i4.6320.

Ferreira, F., and M. Ravallion. 2009. Poverty and Inequality: The Global Context. In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality, ed. W. Salverda, et al., 599–636. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ghawana , T. 2008. Flowering Economy of Naivasha Impacts of Major Farming Systems on the Local Economy. Enschede: International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation.

Gitonga, K. 2016. Kenya Corn, Wheat and Rice Report. Global Agriculture Information Network.

Go, D., D. Nikitin, X. Wang, and H.-F. Zou. 2007. Poverty and inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Literature survey and empirical assessment. Annals of Economics and Finance 8: 251–304.

Haughton, J., and R.K. Shahidur. 2009. Handbook on poverty + inequality. The World Bank 53 (9): 1689–1699. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Basic Report on Well-Being in Kenya. Kenya integrated Household Budget survey (KiHBs). Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Lazaridis, P. 2000. Decomposition of Food Expenditure inequality: An application of the extended Gini coefficient to Greek Micro-data. Social Indicator Research 52: 179–193.

Lerman, I.R., and S. Yitzhaki. 1985. Income inequality effects by income source: A new approach and applications to the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics 67: 151–156.

Malá, Z., and G. Červená. 2012. The relation and development of expenditure inequality and income inequality of Czech households. Economic Annals, LVI I (192): 55–78.

Ministry of Agriculture,Livestock And Fisheries. 2019. National Root And Tuber Crops Development Strategy 2019–2022. Republic Of Kenya.

Ministry of Agriculture. (n.d.). National Rice Development Strategy (2008–2018). Republic of Kenya.

Muthoni, J., and D.O. Nyamongo. 2010. Traditional food crops and their role in food and nutritional security in Kenya. Journal of Agricultural & Food Information 11 (1): 36–50.

Odusola, A., G.A. Cornia, H. Bhorat, and P. Conceição. 2017. Income Inequality Trends in sub-Saharan Africa. Divergence, Determinants and Consequences. New York: UNDP.

OECD. 1982. The OECD List of Social Indicators. Paris: OECD.

Okojie, C., and A. Shimeles. 2006. Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Synthesis of Recent Research on the Levels, Trends, Effects, and Determinants of Inequality in its Different Dimensions. Report of the Inter-Regional Inequality Facility. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Onyango, A.O. 2014. Exploring options for improving rice production to reduce hunger and poverty in Kenya. World Environment 4 (4): 172–179. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.env.20140404.03.

Republic of Kenya. 2013. County Integrated Development Plan (2013–2017). Nairobi: Republic of Kenya.

Republic of Kenya. 2016. National Food and Nutrition Security Policy Implementation Framework 2017–2022. Nairobi: Republic of Kenya.

Republic of Kenya. 2011. National Food and Nutrition Security Policy. Nairobi: Government of Kenya.

Sassi, M. 2012. Short-term determinants of malnutrition among children in Malawi. Food Security 4 (4): 593–606.

Sassi, M. 2015. Seasonality and trends in child malnutrition: Time-series analysis of health clinic data from the Dowa District of Malawi. Journal of Development Studies 51 (12): 1667–1682.

Sassi, M. 2018. Understanding Food Insecurity—Key Features, Indicators, and Response Design. Cham: Springer.

Sassi, Maria. 2019. Seasonality and Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture in Kenya: Evidence from Mixed-Methods Research in Rural Lake Naivasha Basin. Sustainability. 11: 6223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226223.

Sing, A. 2015. The changing structure of inequality in India, 1993–2010: Some observations and consequences. Economic Bulletin 35 (1): 590–603.

Stark, O., and S. Yitzhaki. 1982. Migration, growth, distribution and welfare. Economics Letters 10: 243–249.

Stark, O., J.E. Taylor, and S. Yitzaki. 1986. Remittances and inequality. Economic Journal, 722–740.

Stuart, A. 1954. The correlation between variate-values and ranks in samples from the continuous distribution. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 7: 37–44.

UNDP. 2019. Human Development Report 2019 Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century. (Director: Pedro Conceição, Ed.), United Nations Development Programme (p. 366). New York, USA. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf

USAID. 2012. Kenya Maize Development Programme II Performance Evaluation-2012. Pan African Research (PARS).

Van de Walle, N. 2009. The Institutional Origins of Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Annual Review of Political Science 12: 307–327.

World Bank. 2013. Global Monitoring Report 2013: Monitoring the MDGs. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

WFP. 2016. Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Survey: Summary report Kenya 2016. World Food Programme, 1–12.

Yitzhaki, S. 1982. Stochastic dominance, mean variance and Gini’s mean difference. American Economic Review 72: 178–185.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.. This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research within the Sustainable Agrifood Systems Strategies (SASS) project awarded as of relevant national interest [Delibera n. 71/2016 (17A01736) GU Serie Generale n. 56 del 08-03-2017].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: During the correction process some typos have been overlooked.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sassi, M., Trital, G. & Bhattacharjee, P. Beyond the Annual and Aggregate Measurement of Household Inequality: The Case Study of Lake Naivasha Basin, Kenya. Eur J Dev Res 34, 387–408 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00380-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00380-6