Abstract

This study aims to explore, in the case of the Over-The-Top (OTT) sector, Millennials’ perceptions of brand experience in relation to the well-established brand Netflix. In particular, the work addresses a clusterization of Millennials on the basis of their experience with the brand. The study first explores the theoretical background, highlighting current perspectives on Over-The-Top industry and on brand experience as a strategic process for creating holistic customer value, achieving differentiation and sustainable competitive advantage. Second, it offers a quantitative study (using a survey) and highlights the principal results related to the brand. Moreover, this work will attempt to use cluster analysis methodology exploiting brand experience validated scale and other related brand and behavioural constructs to cluster consumers. Both academics and marketing managers should focus on approaches able to deliver strong and memorable brand experiences. A positive and durable brand experience is related to other important consequences for consumer action and behaviour, such as the willingness to place brand trust, consumer loyalty towards the brand, an enduring consumer-brand relationship, repurchase intentions, and lastly, the long-term life of the brand

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Brand experience has emerged as an important marketing concept aimed at creating unique, pleasurable and memorable experiences. It is a relatively established concept in both theory and practice, which has gained greater attention in recent decades, particularly in the last three decades. Furthermore, it has lived a sort of renaissance in the last years (Andreini et al. 2018). Scholars and marketers define it as a strategic process for creating holistic customer value, achieving differentiation and sustainable competitive advantage (Carbone and Haeckel 1994; Pine and Gilmore 1998; Shaw and Ivens 2002; Gentile et al. 2007; Verhoef et al. 2009; Schmitt 2009; Brakus et al. 2009).

Currently, traditional goods or services value propositions are no longer effective when involving customers or creating differentiation, and brands need to focus on the emotional and experiential facets of consumption (Holbrook and Hirschman 1982). Thus, with the same level of importance given to goods and services functional benefits, a shift towards memorable, satisfying and total experiences is required (Carbone and Haeckel 1994). On this point, Gronroos (2006) states that “customer value is not created by one element alone, but by the total experience of all elements.” On this basis, organizations are reformulating their strategies in order to develop an offering that is capable of delivering “personalized, co-created experiences” (Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004). This shift means managing brands and businesses from another more holistic perspective (e.g., the experiential perspective). It needs the development of new capabilities and skills in creating and managing thrilling consumer experiences that provide satisfying experiential memories in the consumer mind.

Moreover, the importance of this topic is seen by the fact that managing each consumer experience is perhaps one of the most important factors in building brand loyalty (Crosby and Johnson 2007; Brakus et al. (2009); Iglesias et al. 2011; Khan and Fatma 2017). Moreover, many scholars also believe that experiences resulting from various interactions with brands have a substantial impact on other important variables of consumer behaviour (Pine and Gilmore 1998; Schmitt 1999; Brakus et al. 2009).

Customer trust and loyalty towards a brand have traditionally been regarded as a fundamental determinant of long-term positive customer behaviour. The more satisfied and loyal a customer is with respect to a brand, the greater is his or her repurchase intention and, ultimately, the brand wealth.

The concept of brand experience has been explored several times and in several areas such as FMCG, fashion, apparel and food sectors during these last years (Brakus et al. (2009), Khan and Fatma 2017; de Oliveira Santini et al. 2018; Das et al. 2019) using empirical models tested with SEM technique or analogues. Although this interest, to the best of our knowledge, this concept has not been investigated yet in the particular Over-The-Top (OTT) sector who is living a period of rapid expansion, as better explained later, determining the attention of academics, practitioners and governments. As enlightened better far ahead, OTT sector refers to video contents provided via a high-speed Internet connection rather than a cable or satellite provider (some of the main player are Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, Disney+).

Another mega-trend over the past few years is the importance given to the consumer segmentation in order to deliver the most personalized and satisfying experience. According to many important authors, segmentation is one of the fundamental cornerstones of modern marketing (Kotler 1997). In fact, marketing theory suggests that businesses adopting an appropriate segmentation approach to their consumers can improve their organisational performance (Kotler 1997). The principal logic is that segmentation can enhance marketing effectiveness and increase an organisational ability to derive competitive advantage from marketing opportunities (Beane and Ennis 1987; Weinstein 1987). Furthermore, on this point, it should be said that great importance today is given to specific clusters of customers because it allows brands to deliver the best possible experience among their variegated targets.

This work will focus on Millennials generation for many reasons. Millennials (or Generation Y) characterize the cohort born between 1982 and 2000 (Strauss and Howe 2000). From 2017 this generational cohort has exceeded the Baby Boomers spending power and because of its growing market power, it currently represents the focus of marketers’ targets (Beuchamp and Barnes 2015; Moore 2012). Millennials are moreover important for the investigated sector of OTT because represent the first high-tech generation, preferring innovative brands, goods or services (Norum 2003; Moore 2012). Finally, being the highest technologically savvy cohort, they tend to share both delighting and bad brand experiences also through their social networks (Gurau 2012). Relating to the above mentioned Millennials’ features it could be interesting to explore this generation related to an Over-The-Top brand, such as Netflix especially because, to date, research has not investigated yet the relation among the construct of brand experience in OTT sector in the case of Millennials generational cohort.

Thus, drawing on the above, this study aims to explore, in the case of the OTT sector, Millennials’ perceptions of brand experience in relation to the well-established brand Netflix.

In particular, the study addresses the following research questions: Do Millennials share similar perceptions of brand experience? How can Millennials be clustered on the basis of their experience and other brand-related constructs (brand loyalty, brand trust and brand originality)?

To answer these questions, this study first explores the theoretical background, highlighting current perspectives on brand experience. Second, it offers a quantitative study (using a survey) and highlights the principal results related to the brand.

At the same time, given that most of the previous researches used empirical models tested statistically with SEM technique or similar, this work will attempt to use cluster analysis methodology exploiting brand experience validated scale and other related brand and behavioural constructs to cluster consumers. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, following the study by Zarantonello and Schmitt (2010), this is the first study that attempts to group consumers with cluster analysis on the basis of experiential aspects. As said, the research uses Netflix as a case study, one of the most important OTT players today and because to date, there is been no research on brand experience in this particular sector.

Theoretical framework

Netflix consumption

Just before analyze the brand selected for this study is important to frame the reference market. Over-The-Top (OTT media service) industry refers to streaming media services offered directly to consumers (e.g. subscribers) via Internet. Companies act as a provider or distributor of contents bypassing cable, broadcast, and satellite television platforms. The term often is a synonymous of subscription-based video-on-demand (SVoD) services that offer access to film and television contents (including new and original movies of series specifically produced by the Over-The-Top company, as well as existing contents acquired from other producers). Over-The-Top services are typically availed via websites on personal computers, via apps on mobile devices (such as smartphones and tablets), digital media players (including video game consoles), as well as televisions with integrated Smart TV networks. Some of the main worldwide players are Netflix, Hulu, Disney + and Amazon Prime Video.

Netflix—one of the major global Over-The-Top companies—was the brand selected for this study for two main reasons: (1) the brand has high brand awareness (Interbrand 2020) and (2) it is a very well-known brand. Moreover, Netflix is an innovative and growing brand in the media industry and there is no research on brand experience regarding this kind of companies.

Prior to the advent of Netflix, consumers went to the cinema, rented VHS tapes and later DVDs, and viewed whatever was being broadcasted on television. In the present time, consumers can stream content instantly to any device, anywhere, anytime. Thus, from relatively modest beginnings as a DVD-by-mail service, Netflix has grown into one of the most influential media streaming services in the world. The Company was one of the first to see the potential of streaming technology and began to convert to a subscription video-on-demand model in 2007. Since this transition, annual revenue has grown from 1.36 billion to around 15.8 billion US dollars in just ten years (total Netflix 2019 revenue is $20.2 billion) (Businessofapps.com 2020). The number of Netflix subscribers has followed a similar trend, growing from less than 22 million in 2011 to nearly 195 million at the end of 2020 (Statista 2020).

Therefore, Netflix has changed how consumers access film and TV. Consumers are no longer limited to the TV and compelled to sit through commercials. They now have accessible contents and prefer the flexibility of viewing what they want, when they want.

One of the most significant factors for consumers deciding how to view content is scheduling. Consumers would rather avoid paying for content they are unlikely to watch. Netflix spent a staggering $17,3 billion on content in 2020, with around 85% of that going to original shows. Original content is what stands out to viewers (Forbes 2019). They can access multiple platforms in multiple places and screens but unusual content can only be found on Netflix. From the above, it is not difficult to understand how the concept of experience, and brand experience, has become a crucial element in this type of sector.

The concept of brand experience and its related constructs

Traditionally brands were focused on managing the functional aspects of their offering. As has been widely pointed out over the past years, they did not manage strategically the emotional attributes (Shaw and Ivens 2002). Although functional aspects are essential to achieve customer satisfaction (Mosley 2007), brands cannot focus solely on ensuring functional efficiency above all else, if their interest lies in differentiating and delivering a strong and positive brand experience (Westbrook and Oliver 1991). On this basis, brands that are capable of conveying a superior brand experience can elicit positive behavioural outcomes from their consumers, building important relations such as brand trust, brand loyalty, and brand equity (Brakus et al. 2009; Biedenbach and Marell 2010; Iglesias et al. 2011; Jung and Soo 2012; Zarantonello and Schmitt 2013; Lin 2015; Khan and Fatma 2017; de Oliveira Santini et al. 2018; Das et al. 2019).

From an academic point of view, revisiting the literature on brand experience some important features of this hyped marketing construct begin to emerge.

First of all, brand experience can be conceptualized as a multidimensional construct involving cognitive, emotional, behavioural, sensorial, social, and spiritual responses to all interactions with a firm (Schmitt 1999, 2009; Brakus et al. (2009); ; Lemon and Verhoef 2016; Bolton et al. 2014; Gentile et al. 2007; Lemke et al. 2011; Verhoef et al. 2009).

Secondly, brand experience can also be viewed as a psychological construct. In fact, every interaction, and so every experience, is a reflection of internal, subjective and unique mental processing by a consumer (Brakus et al. (2009); Andreini et al. 2018; Carbone and Haeckel 1994; Palmer 2010; de Oliveira Santini et al. 2018; Das et al. 2019).

A third important feature of brand experience is that it can be co-created through an alignment between the customer goals and the marketing offering. Thus, the consumer becomes co-creator of the experience (Andreini et al. 2018; Black and Veloutsou 2017; Chandler and Lusch 2015; De Keyser et al. 2015; Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004) and he or she can be viewed as an actor in the experiential process (Jain et al. 2017).

Moreover, it is also important to recognize brand experience as a consequential process shaped by multiple factors, which at the same time produces its own consequences of its own. That is to say, once the experience between consumer and brand has taken shape, the experience affects consumer behaviour (Morgan-Thomas and Veloutsou 2013; Khan and Fatma 2017).

Lastly, brand experience puts the basis for a holistic evaluation of the brand (Khan and Rahman 2015; Nysveen et al. 2013). Thus, behavioural intentions are influenced by emotions during the pre, actual, and post-consumption stages (Oliver 1999; Cronin et al. 2000; Barsky and Nash 2002; Palmer 2010).

Building on this, it is consequent to note that even if the brand has provided all the functional, emotional and experiential aspects for achieving positive customer affective and cognitive behaviour, each individual can nonetheless perceive all these inputs in quite different ways, implying that each customer may develop diverse behavioural responses, such as brand loyalty, brand trust and repurchase intention (Brakus et al. 2009; Andreini et al. 2018; Khan and Fatma 2017).

According to the literature, brand experience is linked to a number of behavioural constructs. Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) define brand trust as “the willingness of the average consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function.” Doney and Cannon (1997) suggest that the construct of trust comprehends a "calculative process" based on the capability of a subject to maintain over time its promises and on an evaluation of the costs versus benefits in remaining in the relationship. Thus, trust is an expectancy of positive (or at list nonnegative) outcomes that one can receive based on the expected action of another part (e.g. a brand) (Bhattacharya et al. 1998). Moreover, authors highlight that trust regards an inference about the goodwill of the brand to performance in the best interests of the consumers based on shared objectives and values (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). Trust is therefore a dimension that is established over time. Consumers, desiring a positive experience and at the same time trust the brand who provide the service or product (Kim et al. 2011). Thus, more recently brand trust has been defined as ‘‘a feeling of security held by the consumer in his/her interaction with the brand, such that it is based on the perceptions that the brand is reliable and responsible for the interests and welfare of the consumer’’ (Ha and Perks 2005). Building on this definition and in according with Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Aleman (2001) it can be said that if a consumer feels a sense of confidence during its journey with a brand it will likely to establish a good brand experience. In other words, consumers can generate a better experience interacting with a brand when during this process he can feel a sense of trustworthiness toward that brand (Rose et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2011; Morgan-Thomas and Veloutsou 2013; Chen et al. 2014).

Second and third constructs taken into consideration for this study are brand loyalty and repurchase intention, which are moreover and in a certain sense very correlated. Literature shows a strong relationship between brand experience and brand loyalty as demonstrated by numerous researches (Brakus et al. (2009), Iglesias et al. 2011; Khan and Fatma 2017). Oliver (1999, p. 34) defines brand loyalty as a “deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize a pre- ferred product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same brand or same brand-set purchasing, despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behaviour”. From this first definition Chaudhuri and Holbook (2001) recognize two sub-dimensions of brand loyalty: Attitudinal brand loyalty that includes a grade of commitment in terms of values associated with the brand and behavioral, or purchase loyalty that consists in repeated purchases of the same brand (Chaudhuri and Hoolbrook 2001). On this point brand loyalty and repurchase intentions are correlated since companies have started to measure loyalty as a high proportion of the same brand choice, a high intention of positive word-of-mouth and high rate repurchase intention (Yi and La 2004). This means that even if the relationship between brand loyalty and repurchase intentions is more complicated that it appears it is reasonable assume a strong relationship between these two constructs.

Drawing on this reasoning, it is plausible study consumers taking into consideration this four variables simultaneously. It is therefore clear that it is important to try and understand how consumers can, on the one hand, be clustered according to their experiences; and, on the other hand, according to their behavioural responses.

The Millennials generational cohort

Millennials, broadly defined as the Generation Y (Howe and Strauss 2000; Meister and Willyerd 2010; Wilson and Gerber 2008) depict the generational cohort born between 1982 and 1995 (Strauss and Howe 2000). It presently represents the focus of academics and practitioners’ interests above all because by 2017 this cohort has surpassed the Baby Boomers spending power and currently this is the cohort with the most important growing spending power (Beuchamp and Barnes 2015; Moore 2012).

Millennials group is the chosen cohort in this study for many reasons. First of all, they are important for the investigated Over-the-Top industry because they are early adopters of new technologies and extensive users of the internet, they represent the first high-tech generation and usually they looking for innovative brands and experiences (Norum 2003; Moore 2012). Additionally, the emotional value of a brand has a more marked effect on satisfaction than economic value (Eastmann and Liu 2012; Burnsed and Bickle 2015). Finally, they want brands mirroring their personality and showing consistency between promise and delivery, otherwise the decline of trust may happen (Gurău 2012; Pattuglia and Mingione 2017). Being the highest technologically savvy cohort, they tend to share both delightful and bad brand experiences through their social networks.

Drawing on the above and given also many recent studies about this two buzzed topics (Millennials and brand experience) (Lantos 2014; de Kerviler and Rodriguez 2019; Jiménez Barreto et al. 2019) the relation about Millennials perception of brand experience related to an in ferment industry could be interesting to explore because of the great modernity of the subjects and also because to the best of authors’ knowledge no studies until now have explored these themes intertwined.

Methodology

To measure attitudes towards the OTT Company Netflix, a data collection questionnaire consisting of an exhaustive list of 23 items (with control questions) was developed using a convenience sampling procedure. To answer to the initial research questions this study employed a quantitative procedure, using at the beginning the reliability and factor analysis to ensure the validity of all the constructs and, after that, data were analysed through the cluster analysis methodology (with hierarchical method), performed on SPSS in order to investigate if some consumers showed similar characteristics or not.

Data were gathered through an internet survey (uploaded to the Netflix online communities and blog) that was carried out in Italy (Italian consumers) in March 2019 with the millennial generation as target. Even if the literature about millennials is sometimes divergent in terms of age range, as Millennials we targeted people born between 1982 and 2000 (Howe and Strauss 2000).

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first section gathered standard demographic information such as age, region of origin, gender, and education level. The second part concerned behavioural data regarding Netflix viewing and consumption. To set up the third section of the survey (see Table 1), the study adapted scale items of four constructs (brand experience, brand loyalty, brand trust and repurchase intentions) from existing literature. A 12-item scale given by Brakus et al. (2009), which has been applied consistently in the literature, was used to measure brand experience. Brand loyalty was measured with a four-item scale recommended by Odin et al. (2001). Brand trust was based on the survey used by Sung and Kim (2010) with a four-item scale. Lastly, to measure repurchase intentions, we adapted a three-item scale from the study of Hsu et al. (2014). A seven-point Likert scale was used in all cases.

Actually there was a previous screening question at the very beginning of the questionnaire that was: “Are you a Netflix subscriber?” with option to flag “yes” or “no” allow the respondent to continue with the questionnaire only if the answers would “yes.” This choice was made by the awareness that only a subscriber of Netflix would have answered in reliable way to experience, loyalty or repurchase questions.

Findings

The survey resulted in a total of 520 responses, though 81 respondents were not Netflix subscribers (for the initial question: “Are you a Netflix subscriber?” they flagged “no”). Consequently, all 81 non-subscriber questionnaires were deleted from the sample. This decision was made on the basis that many of the questions concerned behaviour based on the consumption and usage of Netflix, and thus in order to avoid discrepancies and low reliability those questionnaires were excluded. Therefore, the final survey resulted in 438 usable responses.

The table below shows some descriptive statistics.

The data was further analysed for its reliability by measuring Cronbach’s alpha for all the scales used in this research. Table 2 presents the results of the reliability test.

As suggested in the literature (Fornell and Larcker 1981), all Cronbach alpha values were found to be above 0.7 in the study, which confirms the internal consistency of the constructs.

Before proceeding with the cluster analysis, constructs were further tested with their discriminant validity. Therefore, a Factor Analysis with principal component method was performed on SPSS.

As shown in the scree-plot (Fig. 1), Factor analysis confirmed 4 different variables (Gorsuch 1983), as expected from the questionnaire. Moreover, Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were estimated to examine the internal consistency and validity of each construct. Studies recommend that for CR the generally accepted threshold level for these tests is 0.7 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). All CR values were found to be above 0.7 in the study (see Table 3), which confirms the internal consistency of the constructs. Also, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981), to clear the convergent validity test, AVE values should exceed 0.5. AVE values exceeded the benchmark of 0.50, indicating that all values satisfied the suggested criteria (see Table 4).

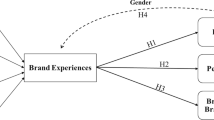

In order to investigate similarities or dissimilarities among consumers this study adopted the cluster analysis methodology to group all those consumers that showed similar characteristics. Thus, as a next step, hierarchical clustering analysis using Ward’s method, which has been considered an effective tool to examine multidimensional constructs (Staake et al. 2012) and performed with SPSS software, was used for clustering consumers. Since the cluster analysis showed 4 different but homogeneous clusters (see the dendrogram in the Fig. 2), with different scores, meanwhile was created a matrix using two (brand experience and brand loyalty) out of four variables investigated, to map in a coherent way the consumers grouped in clusters and as further step all the four constructs were used to analyze each cluster.

Thus, through consumer feedback obtained in the survey and collected data, 4 clusters contained within a grid were created (Fig. 3). As said, the level of brand experience (from non-positive “-” to positive “ + ”) forms the x-axis; whereas the brand loyalty level (from low “-” to high “ + ”) forms the y-axis.

The nomenclature was further created in order to mirror and reflect with just a word the consumers’ groups. Thus, the emerged taxonomy from the 4 clusters is the following:

-

Positive brand experience and high brand loyalty: the Addicted

-

Positive brand experience and low brand loyalty: the Jumpers

-

Non-positive brand experience and high brand loyalty: the Trapped

-

Non-positive brand experience and low brand loyalty: the Strangers

As mentioned, every cluster reveals, in addition to different levels of brand experience and brand loyalty, a different grade of the two other behavioural variables: the willingness to subscribe again (e.g., repurchase intentions) and an inclination to confidence in that brand (e.g., brand trust). Figure 4 depicts the average scores of each variable per each cluster.

Discussion

To date, a majority of studies and research on brand experience have focused mainly on the relationships between the concept of brand experience and other related brand constructs in order to identify possible antecedents and outcomes.

Findings in the present study reveal a new way to view (Italian) young consumers in relation to their OTT consumption, in particular in the case of Netflix.

The first group to emerge is that of the “Addicted”. They undergo a strong and positive experience and thereby become more loyal towards that brand, as shown in previous research (Brakus et al. (2009); Iglesias et al. 2011; Khan and Fatma 2017). Moreover, they feel a large sense of trust and will likely renew their subscription over successive months (high level of repurchase intention).

The second group, termed the “Jumpers”, is a whole new level. Although the brand experience with Netflix is positive (even if perhaps lower than the Addicted), they do not feel at all loyal toward this brand. The sense of trust is medium–low, and very likely they will not renew with Netflix and will change their OTT membership as soon as they can.

The third group includes the “Trapped”, people who have a Netflix subscription yet do not achieve a strong and positive brand experience. Similar to the Addicted, they are loyal consumers but such loyalty is due to functional, personal, or objective factors rather than a sense of delight or satisfaction with respect to the brand.

Lastly, the group termed the “Strangers” concerns all those people who are Netflix consumers yet will likely change the OTT brand or in any case, will not continue their annual subscription. All the brand experience, brand loyalty, brand trust and repurchase intentions levels are very low.

From the preceding observations, it can be said that the present study enhances the knowledge concerning the brand experience phenomenon in various ways.

The results support brand experience as an important variable related to other important consumer behavioural responses, such as brand loyalty, brand trust and repurchase intentions (Brakus et al. 2009; Biedenbach and Marell 2009; Iglesias et al. 2011; Sahin et al. 2012; Jung and Soo 2012; Zarantonello and Schmitt 2013; Lin 2015; Khan and Fatma 2017) but explore this construct from another point of view to add knowledge on this field.

As with previous findings, it could be noted that although the many efforts to personalize the offering with the so called “recommended for view” this research carries out the understanding that now more than ever is essential to clustering and segmenting own consumers on the basis of the behavioural characteristic. This can ensure the transition from good brand experience to a high level of brand equity (Iglesias et al. 2011; Zarantonello and Schmitt 2013; Lin 2015).

Moreover, the segmentation that emerges can represent a starting point for qualitative research that contributes to theoretical advances in brand experience.

Future research could examine all these relationships in other contexts, bringing about a deeper and clearer understanding of the effects of brand experience on consumers.

Managerial implications

The present study, in addition to the aforementioned theoretical contributions, highlights relevant implications for practitioners and marketing managers.

Firstly, results highlight the fact that marketing managers should invest in strategies able to provide strong and memorable brand experiences. This is because a positive and enduring brand experience can trigger other important consequences for consumer action and behaviour, such as the willingness to place brand trust, consumer loyalty towards the brand, an enduring consumer-brand relationship, repurchase intentions, and lastly, the long-term life of the brand. This is especially true and necessary in the OTT sector because the nature of the industry is highly innovative and variable.

Secondly, OTT managers and marketers should make efforts regarding some core features and touchpoints to create a strong and coherent brand offering (and therefore influence Millennials’ expectations) and to deliver it as promised.

From a more operational approach, this study suggests marketers should understand their consumers as much as possible; in particular, managers need to design strategies to preserve “addicted” and “trapped” Millennials, enlarging these groups by dynamically managing a sophisticated algorithm in Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system. This could be useful, especially because in the OTT environment consumers decide which OTT platform to subscribe to, not only for the mere satisfaction of a primary need (simply viewing films or series) but also to receive gratifying brand experience (thanks also to a sense of community, fluency and the user friendly portal).

The findings also highlight that if consumers find a brand satisfying as well as in line with what they want, they become more inclined to remain with that brand to gain and share new and positive brand experiences with other consumers on a daily basis.

Another important consequence is, therefore, the need for marketers to develop marketing strategies that are enticing, emotional, and personalized for all consumer types.

Moreover, nowadays, with the rapid evolution of the internet and related technologies, marketing and communication managers need to better communicate the brand and improve the targeting of their digital communication campaigns—an aspect that is of great importance in the case of Millennials. They would more easily connect with the one-to-one logic, develop greater satisfaction, and in turn develop loyalty to the brand. This becomes valid for each type of segment.

Segmentation also helps businesses allocate financial and other resources more effectively (McDonald and Cristopher 2003). By focusing these resources on the most attractive areas, segmentation encourages businesses to play better with their strengths.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Although Netflix is one of the major companies in the OTT industry, this research regards a single case. Moreover, the study was carried out in a single country. Further research should aim to extend this result through a multi-brand investigation. Furthermore, findings are context-specific, and therefore future studies should explore other countries and generational cohorts to compare them and to create an ad hoc taxonomy for each.

References

Andreini, D., G. Pedeliento, L. Zarantonello, and C. Solerio. 2018. A renaissance of brand experience: Advancing the concept through a multi-perspective analysis. Journal of Business Research 91: 123–133.

Barsky, J., and L. Nash. 2002. Evoking emotion: Affective keys to hotel loyalty. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 43 (1): 39–46.

Beane, T.P., and D.M. Ennis. 1987. Market segmentation: A review. European Journal of Marketing 21 (5): 20–42.

Beauchamp, M.B., and D.C. Barnes. 2015. Delighting baby boomers and millennials: Factors that matter most. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 23 (3): 338–350.

Bhattacharya, R., T.M. Devinney, and M.M. Pillutla. 1998. A formal model of trust based on outcomes. Academy of management review 23 (3): 459–472.

Biedenbach, G., and A. Marell. 2010. The impact of customer experience on brand equity in a business-to-business services setting. Journal of Brand Management 17 (6): 446–458.

Black, I., and C. Veloutsou. 2017. Working consumers: Co-creation of brand identity, consumer identity and brand community identity. Journal of Business Research 70: 416–429.

Bolton, N.R., A. Gustafsson, J. McColl-Kennedy, N.J. Sirianni, and D.K. Tse. 2014. Small details that make big differences: A radical approach to consumption experience as a firm’s differentiating strategy. Journal of Service Management 25 (2): 253–274.

Brakus, J.J., B.H. Schmitt, and L. Zarantonello. 2009. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing 73 (3): 52–68.

Burnsed, K.A., and M.C. Bickle. 2015. Comparison of US generational cohorts’shopping mall behaviors and desired features. International Journal of Sales, Retailing & Marketing 4 (4): 18–30.

Carbone, L.P., and S.H. Haeckel. 1994. Engineering customer experiences. Marketing Management 3 (3): 8–19.

Chandler, J.D., and R.F. Lusch. 2015. Service systems: A broadened framework and research agenda on value propositions, engagement, and service experience. Journal of Service Research 18 (1): 6–22.

Chaudhuri, A., and M.B. Holbrook. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing 65 (2): 81–93.

Chen, H., A. Papazafeiropoulou, T.-K. Chen, Y. Duan, and H.-W. Liu. 2014. Exploring the commercial value of social networks: Enhancing consumers’ brand experience through Facebook pages. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 27 (5): 576–598.

Cronin, J.J., Jr., M.K. Brady, and G.T.M. Hult. 2000. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing 76 (2): 193–218.

Crosby, L.A., and S.L. Johnson. 2007. Experience required: Managing each customer’s experience might just be the most important ingredient in building customer loyalty. Marketing Management 16 (4): 20.

Das, G., J. Agarwal, N.K. Malhotra, and G. Varshneya. 2019. Does brand experience translate into brand commitment?: A mediated-moderation model of brand passion and perceived brand ethicality. Journal of Business Research 95: 479–490.

Delgado-Ballester, E., and J. Luis Munuera-Alemàn. 2001. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing 35 (11/12): 1238–1258.

de Kerviler, G., and C.M. Rodriguez. 2019. Luxury brand experiences and relationship quality for Millennials: The role of self-expansion. Journal of Business Research 102: 250–262.

De Keyser, A., J. Schepers, and U. Konuş. 2015. Multichannel customer segmentation: Does the after-sales channel matter? A replication and extension. International Journal of Research in Marketing 32 (4): 453–456.

de Oliveira Santini, F., W.J. Ladeira, C.H. Sampaio, and D.C. Pinto. 2018. The brand experience extended model: A meta-analysis. Journal of Brand Management 25 (6): 519–535.

Doney, P.M., and J.P. Cannon. 1997. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing 61 (2): 35–51.

Eastman, J.K., and J. Liu. 2012. The impact of generational cohorts on status consumption: An exploratory look at generational cohort and demographics on status consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29 (2): 93–102.

Fornell, C., and D.F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50.

Gentile, C., N. Spiller, and G. Noci. 2007. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal 25 (5): 395–410.

Gorsuch, R.L. 1983. Factor analyses. Hillsdale: Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

Grönroos, C. 2006. On defining marketing: Finding a new roadmap for marketing. Marketing Theory 6 (4): 395–417.

Gurău, C. 2012. A life-stage analysis of consumer loyalty profile: Comparing Generation X and Millennial consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29 (2): 103–113.

Holbrook, M.B., and E.C. Hirschman. 1982. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research 9 (2): 132–140.

Hsu, M.H., C.M. Chang, K.K. Chu, and Y.J. Lee. 2014. Determinants of repurchase intention in online group-buying: The perspectives of DeLone & McLean IS success model and trust. Computers in Human Behavior 36: 234–245.

Kim, S., J. Cha, B.J. Knutson, and J.A. Beck. 2011. Development and testing of the Consumer Experience Index (CEI). Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 21 (2): 112–132.

Iglesias, O., J.J. Singh, and J.M. Batista-Foguet. 2011. The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. Journal of Brand Management 18 (8): 570–582.

Jain, R., J. Aagja, and S. Bagdare. 2017. Customer experience: A review and research agenda. Journal of Service Theory and Practice 27 (3): 642–662.

Jiménez Barreto, J., N. Rubio, and S. Campo Martínez. 2019. The online destination brand experience: Development of a sensorial–cognitive–conative model. International Journal of Tourism Research 21 (2): 245–258.

Jung, L.H., and K.M. Soo. 2012. The effect of brand experience on brand relationship quality. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 16 (1): 87–98.

Khan, I., and M. Fatma. 2017. Antecedents and outcomes of brand experience: an empirical study. Journal of Brand Management 24 (5): 439–452.

Khan, I., and Z. Rahman. 2015. Brand experience anatomy in retailing: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 24: 60–69.

Kotler, P. 1967. Marketing management: Analysis planning, and control. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Kotler, P. 1997. Marketing Management Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control, 9th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall International.

Lantos, G.P. 2014. Marketing to millennials: Reach the largest and most influential generation of consumers ever. Journal of Consumer Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-03-2014-0909.

Lemke, F., M. Clark, and H. Wilson. 2011. Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 39 (6): 846–869.

Lemon, K.N., and P.C. Verhoef. 2016. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing 80 (6): 69–96.

Lin, Y.H. 2015. Innovative brand experience’s influence on brand equity and brand satisfaction. Journal of Business Research 68 (11): 2254–2259.

McDonald, M., M. Christopher, and M. Bass. 2003. Market segmentation. In Marketing, 41–65. London: Palgrave.

Meister, J.C., and K. Willyerd. 2010. Mentoring Millennials. Spotlight on Leadership. The Next Generation. Harvard Business Review 88 (5): 67–72.

Moore, M. 2012. Interactive media usage among millennial consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing 29 (6): 436–444.

Morgan-Thomas, A., and C. Veloutsou. 2013. Beyond technology acceptance: Brand relationships and online brand experience. Journal of Business Research 66 (1): 21–27.

Mosley, R.W. 2007. Customer experience, organisational culture and the employer brand. Journal of Brand Management 15 (2): 123–134.

Norum, P.S. 2003. Examination of generational differences in household apparel expenditures. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 32 (1): 52–75.

Nysveen, H., P.E. Pedersen, and S. Skard. 2013. Brand experiences in service organizations: Exploring the individual effects of brand experience dimensions. Journal of Brand Management 20 (5): 404–423.

Odin, Y., N. Odin, and P. Valette-Florence. 2001. Conceptual and operational aspects of brand loyalty: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research 53 (2): 75–84.

Oliver, R.L. 1999. Whence consumer loyalty? The Journal of Marketing 63: 33–44.

Palmer, A. 2010. Customer experience management: A critical review of an emerging idea. Journal of Services Marketing 24 (3): 196–208.

Pattuglia, S., and M. Mingione. 2017. Towards a new understanding of brand authenticity: Seeing through the lens of Millennials. Sinergie Italian Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.7433/SRECP.FP.2016.29.

Pine, B.J., and J.H. Gilmore. 1998. Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review 76: 97–105.

Prahalad, C.K., and V. Ramaswamy. 2004. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 18 (3): 5–14.

Rose, S., N. Hair, and M. Clark. 2010. Online customer experience: A review of the business-to-consumer online purchase context. International Journal of Management Reviews 13 (1): 24–39.

Sahin, A., C. Zehir, and H. Kitapci. 2012. The effects of brand experience and service quality on repurchase intention: The role of brand relationship quality. African Journal of Business Management 6 (45): 11190–11201.

Schmitt, B. 1999. Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management 15 (1–3): 53–67.

Schmitt, B. 2009. The concept of brand experience. Journal of Brand Management 16 (7): 417.

Shaw, C., and J. Ivens. 2002. Building great customer experiences, vol. 241. London: Palgrave.

Staake, T., F. Thiesse, and E. Fleisch. 2012. Business strategies in the counterfeit market. Journal of Business Research 65 (5): 658–665.

Strauss, W., and N. Howe. 2000. Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York: Vintage.

Sung, Y., and J. Kim. 2010. Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychology & Marketing 27 (7): 639–661.

Verhoef, P.C., K.N. Lemon, A. Parasuraman, A. Roggeveen, M. Tsiros, and L.A. Schlesinger. 2009. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing 85 (1): 31–41.

Yi, Y., and S. La. 2004. What influences the relationship between customer satisfaction and repurchase intention? Investigating the effects of adjusted expectations and customer loyalty. Psychology & Marketing 21 (5): 351–373.

Weinstein, A. 1987. Market segmentation. Chicago, IL: Probus Publishing Company.

Westbrook, R.A., and R.L. Oliver. 1991. The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research 18 (1): 84–91.

Wilson, M., and L.E. Gerber. 2008. How generational theory can improve teaching: Strategies for working with the millennials. Currents in Teaching and Learning 1 (1): 29–44.

Zarantonello, L., and B.H. Schmitt. 2010. Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. Journal of Brand Management 17 (7): 532–540.

Zarantonello, L., and B.H. Schmitt. 2013. The impact of event marketing on brand equity: The mediating roles of brand experience and brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising 32 (2): 255–280.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amoroso, S., Pattuglia, S. & Khan, I. Do Millennials share similar perceptions of brand experience? A clusterization based on brand experience and other brand-related constructs: the case of Netflix. J Market Anal 9, 33–43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-021-00103-0

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-021-00103-0