Abstract

Mobilisations opposed to vaccinations and other Covid-19-related measures have dominated the protest arena in the recent years of the pandemic. Radical right collective actors, whether newly emerging or revitalised, have successfully shaped public discourses and gained significant roles on the streets and in party politics. This paper analyses the radical right (RR) mobilisation that takes place in response to the pandemic, looking at the main actors, demands and strategies behind protest events, and paying particular attention to the relationship between movements and parties. The analysis focusses on Italy and Hungary, two European countries characterised by favourable political opportunities for radical right mobilisation in recent years. The argument is that the pandemic offered a new window of opportunities for the empowerment of (new and old) radical right collective actors, leading, however, to different outcomes in terms of ‘movement–parties’ relations (or ‘movement–parties’ formation). The article draws on a mixed method approach including a protest event analysis based on newspapers and police records (2021–2022), comprising more than 300 events, and 30 in-depth interviews with radical right and anti-vax activists and leaders in both countries. The findings highlight that while health-related demands are the most important issues in both countries, the outcomes of such protests are different, both in terms of the intensity of radical right mobilisation (including violence) and in the movement–party relations. In the Italian case, the protest against vaccines gives birth to a strict division of labour or ‘conflict’ between RR movements (which remained the main actors of the street protest) and political parties (in institutions), while in Hungary the two sides are characterised by ‘cooperation’. These results demonstrate that in the two analysed countries, anti-vax and Covid-19-related protests have different impacts on national politics and the conflict arena, which require investigation of movement–party relations to be fully grasped.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The 'No Green Passes' movement will present itself in the next Italian elections under the label of ‘Freedom Movement’.

The promoter is Franco Corbelli, leader of the ‘Movement for Civil Rights’ during the anti vax protest: ‘"We will unite all the various protests around vaccines in Italy to give voice and representation in Parliament to these people who have been courageously fighting for months against the authoritarian drift of the Italian Government which has brutally suppressed citizens’ rights and freedom".

(https://www.agi.it/cronaca/news/2021-11-02/no-vax-nasce-movimento-per-la-liberta-14413456/)

Introduction

Mobilisations opposed to vaccinations and other COVID-19-related measures have dominated the protest arena during the recent pandemic. New radical right (RR) collective actors have emerged, while others have revitalised, successfully shaping public discourses and gaining significant roles, both on the streets and in party politics.

This study analyses, in a comparative perspective, the radical rightFootnote 1 mobilisation related to the pandemic, with particular attention to the relationship between movements and parties (Cooperation? Conflict? Co-optation?), looking at the main actors organising protest events, their demands, and their strategies (including violence) and relating them to the opportunities of the context and group’s resources (della Porta and Diani 2020). The paired comparison method offers numerous benefits achieving a balanced blend of descriptive depth and analytical complexity (Tarrow 2010).

The analysis of the phenomenon of anti-vaccinationism has received conspicuous attention in recent years (just to quote a few, Harambam and Voss 2021, Eslen-Ziya and Giorgi 2022), with works focussing on the progressive and regressive social reactions in response to anti-containement measures in various countries and from different analytical perspectives (Gerbaudo 2020; Liao 2022; Mathias 2020; della Porta 2022; della Porta and Lavizzari 2022, 2023; Fominaya 2022). In this paper, we adopt a social movement approach applied to the RR (Caiani et al.2012) and focus on Italy and Hungary, two European countries characterised by favourable political opportunities for radical right mobilisation in recent years. Similarities and differences between the different types of radical right-wing groups and countries in both the degree and forms of anti-vax mobilisation are showed and linked to the cultural and political–discursive opportunities of the context. The main assumption is that the pandemic offered a new window of opportunities for the empowerment of (new and old) RR collective actors, leading, however, to different outcomes in terms of ‘movement-parties’ transforming in such a way the political conflict arena (Borbáth et al. 2021).

The article draws on a mixed method approach including a protest event analysis (Hutter 2014) based on newspapers and police records (from the outset of vaccine measures to mid-2022), encompassing over 30 in-depth interviews with radical right and anti-vax activists and leaders in both countries. Moving from a processual and dynamic approach to collective action we will pay close attention to the agents, namely, the actors’ perceptions of the context as well as the groups’ resources, possessed as organisations or created as frames of the protest.

The findings highlight that while health-related demands are the most important issues in both countries, the outcomes of such protests are different, both in terms of the intensity of radical right mobilisation and in the movement–party relations. In the Italian case, the protest against vaccines gives birth to a strict division of labour (when not ‘conflict’, Caiani and Císař 2018) between RR conservative movements (which remain the main actors of the street protest) and political parties; while in Hungary they were characterised by ‘cooperation’ (or indifference), with consequences in the long term such as the consolidation of new RR ‘movement-parties’ in the political system, as showed by the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary elections.

In the following, after illustrating the analytical guiding concepts, our cases and the method (Sects. “Cases and method”), we investigate the intensity and trends of radical right mobilisation in the anti-vax protests in the two countries (Sect. “Empirical analysis—political opportunities and RR anti-vax mobilisation: country and time”), reflecting on the use of different strategies of actions (including violence) and organisational targets, issues and networks (Sect. “The social characteristics of radical right anti-vax mobilisation: which are the most active groups and actors?”, “Radical right anti-vax mobilisation: issues and frames”, “Networks in the anti-vax RR protest and ‘movements–parties’ relations”). In the conclusion (Sect. “Conclusion: pandemic, a similar ‘critical juncture’, two different outcomes of the movement–party mobilisation”) we critically assess the results, reflecting on the changes in radical right politics in the twenty-first century.

The article, contributes, on the one hand, to the literature on contentious politics ‘in times of crisis’, of which the Covid-19 crisis is an example, usually focussed on progressive protests (Gerbaudo 2020); and, on the other hand, on radical right research, usually focussed on party politics and electoral behaviour or right-wing extremism, neglecting regressive movements. It provides an empirical contribution and some conceptual reflections on the relations between various types of actors and strategies, such as movements and parties, in times of increasing street mobilisation of radical right politics (Hunger et al. 2023).

Background and guiding concepts

The radical right in the age of COVID-19 has been studied from a political party perspective (Wheeler 2020), assessing the positive relation between the contexts, that is, the intensity of the pandemic (and the severity of lockdown measures) and the vote for the RR (Peacock and Biernat 2022). Studies suggest a causal connection between vaccine scepticism and support for RR populist parties in Western Europe, particularly in Italy (Kennedy 2019; Rietdijk 2021). In contrast, Heinze and Weisskircher (2022), while observing anti-vax mobilisation in Germany revealed how political parties had responded to street protests, labelling them as ‘pariahs’, i.e. radicals or extremists; and how various containment policy strategies against anti-vaxxers have been implemented by ruling political parties in Europe (Plümper et al. 2021). The anti-vax protest has also been interpreted as ‘anti-politics’ (Russell 2022), and research did shed light on alternative forms of knowledge, which has been produced by anti-vaxxers targeting scientific (i.e. “pseudo-science”, “troll and counter-science”, Eslen-Ziya and Giorgi 2022). The potential of the COVID-19 crisis to foster frame alignment strategies within the field of contestation has been also pointed out (Zeller 2021), as well as the existence of overlapping activism among different types of organisations, overcoming through frame activity possible identity tensions (Rulli and Campbell 2022). Furthermore, scholars suggest that the pandemic brought about changes in collective actors’ tactics in protest (Kowalewski 2021), in times of social distancing.

Against this background, in order to capture a broad picture of the current developments in the RR political mobilisation during the Pandemic, we propose an analysis of the radical right and anti-vax protest as a social movement (see each empirical sections). Indeed, an important aspect to be explored is whether we are witnessing an intensification and hybridisation of street and institutional politics of (RR) mobilisation, which—as we argue in this study—may be enhanced by the Pandemic.

If the radical right has been traditionally addressed through breakdown theories vs. left-wing radicalism analysed from the perspective of mobilisation theories, social movement studies, rarely although increasingly applied to research on the RR (e.g. Caiani et al. 2012; Castelli Gattinara et al 2022), pay more attention to the ‘agents’ and the link between structure and agency. They stress, for right-wing mobilisation too as for any other collective actor, the importance of political opportunities and the ‘framing’ of them (Caiani 2023) instead of ‘grievances’; action repertoires instead of violence or elections; and organisational networks and dynamics rather than structures (della Porta 2012). Consequently, there is a gap in the current literature on the non-institutional side of radical right politics, and more specifically on the interrelation of parties, grassroot movements, and the wider radical right milieu (Malthaner and Waldmann 2014).

If on a macro level, it is generally assumed that collective action results from discontent and relative deprivation related to objective conditions, as the ones brought by the Covid-19 Pandemic, which created societal tensions (van der Zwet et al. 2022), these opened political opportunities to challenge government (Brooks et al. 2020) need to be politicised to become the basis for collective action.

In particular, first of all, we will look at the organisational structure (i.e. networks) of the radical right milieu and the anti-vax contention, considering the complex interplay among various actors linked to each other in co-operative as well as, sometimes, competitive interactions. They (i.e. right-wing actors) are networks of more or less formal groups and individuals, and the extent and structure of these networks defines their mobilising capacity (della Porta 2012).

Second, we suggest that these networks use a broad repertoire of collective action: instead of solely focussing on electoral behaviour or on violent actions, we analyse the different forms of protest used by the radical right to mobilise against vaccines, addressing the ways in which the (perceived) available resources and political opportunities, do influence these strategic choices (including violence). Third, we consider the frames (i.e. issues) through which the collective actors involved in the radical right anti-vax protest construct and communicate their (internal and external) political and social reality, concerning the Pandemic. Ideas play an intermediate role (Laumond 2020), between external factors and individuals, in the emergence of collective action (even radical).

While looking at the trends and characteristics of anti-vax RR mobilisation in the two countries according to a social movement approach in this study we will pay particular attention to ‘movement-parties’. The relations between right-wing movements and parties, or streets and elections (Hutter and Borbáth 2019), can conceptualised at least in two ways (Caiani and Císař 2018). On the one hand the concept of ‘movement-party’ has been elaborated, indicating a new type of political organisation, which is increasingly prominent and successful in mobilising voters (Kitschelt 2006), both on the radical right and the radical left (della Porta et al. 2017) in Europe. They are likely to emerge in times of political and economic crisis, when traditional cleavage structures are transformed and new societal grievances are not addressed by the existing political actors. They usually exhibit a strongly anti-establishment attitude, deploying a populist discourse of ‘us’ (the people) against ‘them’ (the political elite), and drawing on society’s mistrust of the dominant political class in times of crisis. On the other hand, it can conceptualised as relations between the two sides: movements and parties (Rucht 2018). In this study we will look at both dimensions of this novel concept. These relations can take several forms, according to the context of opportunities and constraints, as well as the characteristics of the organisational milieu from which they derive and are embedded in (e.g. strength of RR competing social movements, weaknesses or vacancy of institutional RR parties, Caiani and Císař 2018). They may include: competition (when political parties and social movements struggle to obtain a similar goal)Footnote 2; co-optation/penetration (when there is a top-down relation, e.g. the formal representative subsumes or assimilates the informal representative, but also when the demands voiced by the social movement becomes part of the political party manifesto); cooperation (when a voluntary agreement between a political party and a social movement in which both engage in what they conceive as a mutually beneficial exchange, according to a ‘reformist view’ of representation). Finally, also rejection (with the exclusion of a social movement claim, or the actively repression, silence or social demobilisation of the claims voiced by a social movement performed by a political party) or non-reaction (i.e. indifference) can be possible.

For the sake of this study, focussing on the radical right and anti-vax protests, ‘movement-parties’ are thus considered as a new ‘brand’ of radical right politics, ideally bridging the forms, organisation and practices of political parties and social movements.

Cases and method

The paired comparison provides several advantages: it provides a ‘balanced combination of descriptive depth and analytical challenge’ as an intermediate step in theory-building between single-cases and multi-cases (Tarrow 2010, p. 243). As for cases, this study focuses on anti-vax right-wing protests in Italy and Hungary (January 2021–June 2022), two European countries characterised by favourable ‘political opportunities’Footnote 3 for radical right anti-vax mobilisation, albeit having two institutional contexts (including ‘allies’ in power-i.e. RR political parties in parliament) which are very different in many other respects.

First, both countries were severely hit by the pandemic (Cerqua and Di Stefano 2022),Footnote 4 and are characterised by the presence of a strong RR milieuFootnote 5 (see Table D in the Appendix in Supplementary Material). Italy and Hungary had a similarly strict approach to the COVID-19 crisis in terms of curfews, lockdowns, and vaccination (for a timeline see Table B in the Appendix in Supplementary Material) hence, providing a fertile breeding ground for anti-government sentiment.

However (second), in terms of the institutional context within which the mobilisation of the radical right may take place, the ruling party in Hungary, although not identifiable as a radical right party, takes on some elements of it (Bene and Boda 2021; Batory 2022). In Italy, the pandemic crisis has been managed by a “center-left” government during the first emergency phase and the subsequent vaccination phase, and later by a technical government that included populist and right-wing parties, acting however in continuity with the previous government.

Furthermore (third), in terms of ‘protest policing’, which may affect the intensity and forms of collective mobilisation (della Porta and Diani 2020), there were significant differences between the two countries in how the governments handled public assemblies and political protests. In Hungary, prohibition on public events and gatherings was introduced on 16 March 2020; then, in November, restrictions were tightened. According to the decree, participants in public demonstrations could be fined up to 1450 Euros; moreover, the organisers could be fined up to twice that. On 31 May 2021, the Hungarian government eased the total ban on demonstrations, and finally, on 7 March 2022, all restrictions were lifted. In Italy the ‘policing of protest’ (della Porta and Diani 2020) remained in place, with more restrictions and stronger reactions to demonstrations—making it more likely to radicalise the protest. These differences in the severity of the emergency and each national government’s reactions to it show that more contingent circumstances of politics differ in the two countries.

In terms of methods, we adopted a mixed method approach. First, a protest event analysis (PEA),Footnote 6 based on national newspapers, police recordsFootnote 7 and online news media web pages (Caiani and Susánszky 2020), with the aim of investigating the intensity and characteristics of the anti-vax mobilisation (actors, issues, target, action strategies, etc.) in the two countries.Footnote 8 The protest events related to the anti-vax mobilisation were searched using key words and resulted in 2000 relevant articles found on Italy (IT) and 46 on Hungary (HU), comprising a total of 343 coded protest events (157 in IT and 186 in HU) (for details on the key words, sources and codebook used, see Table C in the Appendix in Supplementary MaterialFootnote 9).

The PEA was integrated with 29 in-depth interviews with RR anti-vax radical right activists and leaders of various organisations in the two countries,Footnote 10 including party and non-party groups (23 interviews in ItalyFootnote 11 and 6 in Hungary; see Table B in Appendix in Supplementary Material), designed to explore the same analytical variables from a more constructivist perspective, focussing on the reasons and rationale of the protest and its forms, beliefs and positions, as well as the actors’ perceptions of the context of political and discursive opportunities and constraints within which their protest was located (for details, see Table A in the Appendix in Supplementary Material).

Empirical analysis—political opportunities and RR anti-vax mobilisation: country and time

In the following section, we look at the degree and characteristics of right-wing and anti-vax protests, as well as their scope and action strategies.

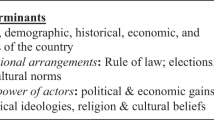

The literature on collective action has emphasised that levels and forms of mobilisation by social movements are strongly influenced by the so-called political and discursive opportunities, namely the set of opportunities and constraints that are offered by the institutional structure and political culture of the political system in which these groups operate (Tarrow 1994; Koopmans 2005). Movement organisations mobilise when and where channels of access open up (or are perceived as such)—which in fact tends to facilitate protest though moderate its form. Furthermore, dynamic and contingent factors (such as the shift in the configuration of allies and opposition, new laws, or changes in power relations) are referred to in order to account for the amount and forms of collective action. While open opportunities imply easy access for new rivals in the political system, the lack (or the closing) of these opportunities often culminates in escalation (della Porta, 1995).

What is therefore the level of mobilisation that characterises the radical right anti-vax protest in Italy and Hungary? Firstly, our protest event data confirm that right-wing mobilisation is a significantFootnote 12—and increasing—aspect in the period under analysis, despite considerable variations over time (Fig. 1): 343 total actions initiated by these groups have been identified (157 in Italy and 186 in Hungary). In both countries, protests started after the first protective measures (e.g. school closures), following a sharp rise in the number of protest events, as the mandatory use of the vaccination certificates was progressively extended to more contexts, with a peak in the last quarter of 2021 (see also della Porta and Lavizzari 2022).Footnote 13 For example, in Italy, the number of RR protest events increased from a few dozen events in the first months of the year (when the vaccines campaign began) to 131 at the end of 2021 (with 3 major peaks of events in April, July and October, which is the month of the violent attack in Rome against the left-wing Union CGIL).Footnote 14 After this period, the intensity of radical right mobilisation significantly declines, and during early 2022, there was a maximum of 12 registered cases per month. Nevertheless, no marked variations across the two contexts exist, with stable or increasing levels of right-wing mobilisation, correlating to the openess/closeness of the institutional opportunities (i.e. more intense when closed, but also more radical when a stricter policing of protest prevails).

As well as the number of actions, the number of participants at RR and anti-vax events is a key factor in RR mobilisation (see Fig. 1b in the online Appendix in Supplementary Material). According to our data, the scale of the anti-vax events organised by right-wing groups in Italy varies a lot with large numbers (such as in the case of the No Green Pass demonstration on 6th of October 2021 in Rome with roughly 15,000 people, or the parade organised by the committee against the Green pass in Milan on 31 July 2021, numbering 10,000) to smaller gatherings (20–30 people). Examples of events mobilising only a couple of dozen participants are the sit-in organised by the Forza Nuova in Rome on the 16th of October 2021, or the occupation of buildings at the University of Turin by the student organisation Studenti no green pass on the 26th of January 2022.

According to our data, the scale (i.e. mobilisation capacity) of anti-vax protest events was smaller in Hungary. The most significant protest eventFootnote 15 (Approx. 2000 protesters) was organised by the Our Homeland Party in collaboration with civil organisations such as the Doctors for Clarity on November 20th, 2021. The recently founded movement-parties (i.e. Normális Élet Pártja, Our Homeland Party) organised numerous (and populated) protests in larger cities as well, with numbers in attendance ranging from a couple of dozenFootnote 16 to a few hundred.Footnote 17

Explaining the patterns in the intensity of mobilisation: the perception of contextual opportunitiess and threats

Hungary: soft repression and unresponsiveness of the power-holders

The fluctuating trends shown by the PEA are confirmed and better explained through our interviews and the actors’ own perceptions of the open or closed opportunities for their mobilisation. In Hungary, what emerged is what we may term: Soft repression and unresponsiveness of the power-holders. When enquiring about interviewees’ perceptions of the political and cultural opportunities as well as constraints of the context for their mobilisation, the activists often cite ‘obstacles’ to their mobilisation: in effect a ‘soft repression’ by the Hungarian state. That is, non-violent techniques applied by authorities against dissidents to demobilise existing and potential activists, (Jämte and Ellefsen 2020) and the low level of citizens’ protest readiness. The former, according to many, comprises stigmatisation, silencing and the use of ‘negative frames in news media’ (Susánszky et al. 2022). In particular, some activists stress the (‘high’) risks of state surveillance for participating in the protest and that many organisations must refrain from discussing sensitive information via video chat platforms (HU.4). Some anti-vax activists complained that the ruling party, Fidesz, interfered with the distribution of the protest campaign propaganda (such as leaflets, and calls for demonstrations). Furthermore, activists perceive the government as unresponsive to their protests (‘..politicians do not respond to us”, HU.4), and their mobilisations as ineffective in influencing COVID-19 policies (i.e. sense of ‘political inefficacy’). Another obstacle to mobilisation is Hungarians indifference to politics, as explained, ‘people only care for their own private life’ (HU.5), they ‘… don’t have the inclination to protest’ (HU.6), and ‘Hungarians are mentally castrated’ (HU.3). In fact, Hungarians are less inclined to participate in protests than citizens of Western European countries (Hooghe and Quintelier 2014; Kostelka 2014). On the other hand, COVID-19 protests receive limited mass media news coverage and any grievances and claims made by different collective actors to their audiences are rarely conveyed (Susánszky et al. 2022).

On the whole, our results demonstrate that Hungarian anti-vax actors perceive a ‘closing space’. Restrictions and soft repression affect different sectors within the entire civil sphere, including human rights, environmental issues and women’s organisations (Gerő et al. 2022).

Italy: changing opportunities and the importance of societal support

Similarly, Italian anti-vax activists consider the political opportunities structure of the context closed to their claims. As in the Hungarian case, all actors interviewed agreed that the parliamentary political parties are completely opposed to their demands, and thus, are considered as ‘the main enemies’ of the movement. Although some Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) members of parliament (MPs)“try to make things less restricted” (IT.3) by listening to activists’ demands, the party officially refuses to make policy initiatives based on the movement’s requests. Moreover, Italian anti-vax protesters believe that the political environment in the country is more hostile too due to increased police repression which has significantly restricted the RR space for political activism. “With the Covid emergency the spaces for the radical right forces were restricted and police repression is stronger than in the past, when they used to tolerate us…now we always need authorization to move” (IT.11). However, the context of opportunities is also seen as dynamic by RR anti-vax activists and positively changing with time,Footnote 18 especially in terms of Italian public opinion as regards the movement’s causes, described as “the most important element affecting (our) protest” (IT.3). In particular, there is a strong correlation both with the movement’s strategies (whether they use violence or not) and with the government’s decision to adopt more restrictive measures. All in all, Italian radical right actors believe that public opinion is less hostile to their ideas than it was before the pandemic “the pandemic made our demonstrations larger, more people came to our demonstrations (IT.1), people that might not share our ideology, but were willing to join us in the streets”, (IT.10 and IT.9). In addition, the mass media, initially perceived as hostile to the anti-vax movement (‘they are aligned to the government’s positions), are seen to be slowly changing their attitudes (e.g. “now they leave us talk a bit, although we are still criticized…”, IT.3).

Contrastingly, in Hungary, mass media appear to have little interest in the anti-vax protest, as was confirmed by our analysis of the media coverage of Covid related protests, which by pro-government media and public media is quite low and/or distorted in reporting anti-vax demonstrations (see Table 1 in Appendix in Supplementary Material).Footnote 19 These results are in line with our interview data since the activists point out that anti-vax protesters “could not establish a relationship with mainstream news media” (HU. 1),Footnote 20 and anti-vax demands remained under-reported in Hungarian media outlets.

The social characteristics of radical right anti-vax mobilisation: which are the most active groups and actors?

Several studies have shown that contextual dimensions alone are not sufficient to describe the forms and development of right-wing mobilisation, which are tied to internal organisational factors.Footnote 21 For example, as social movement scholars suggest, the strategic action options of different types of organisations, beyond being a message that the organisation gives its members (Kitschelt 1988) also include the specific reactions of the groups to the context (the various structural, political, cultural, and technological factors) in which they are embedded and mobilise (della Porta 1995).

Looking more closely at the protagonists of RR anti-vax mobilisation in our analysed period (see Fig. 2, showing the distribution of the protest events by type of actors between 2021–22), we can observe that the most active groups in Italy are political movements (43.3% of cases) with individual/generic right-wing activists accounting for 26.1%, while political parties mostly kept a distance (10.2%). In contrast, political parties play a dominant role in Hungary on the streets (41.4%), but also non-institutionalised actors, like individual activists, were quite active (30.1%). Moreover, the analysis of the organisational structure of the anti-vax field in Italy and Hungary indicates statistically significant cross-country differences (Cramer’s V = 0.43***).

In the category of ‘political parties’, we included groups defining themselves as political parties. In the Italian anti-vax protest arena, Forza Nuova is the most active party, while in Hungary, it is Our Homeland Movement party (Mi Hazánk Mozgalom), a recent formation, which can be defined as a ‘movement-party’. This was founded in 2018 by politicians from the former extreme right party, Jobbik (Pytlas 2015) who emerged as one of the prominent organisers of the protests in the country. The party entered parliament in the 2022 parliamentary elections, winning six seats.

In the category of ‘political movements’, we included those non-institutionalised organisations that do politics as a main activity without participating in elections. In Italy, this includes various student organisations, such as the ‘Studenti contro il Green pass’ that emerged during the anti-vax protest to protest against government measures (i.e. the green pass, lockdown, and vaccines) linked to RR parties, political journals, magazines, and reviews. In Hungary, political movements include traditional radical right organisations such as the Save the Nation Radical Association (Nemzetmentő Radikális Egyesület) and new groups against restrictions (‘Stop restricting our freedom!’ along with single-issue groups like the teacher and healthcare workers’ organisations, as well as Doctors for Clarity and Children’s Health Defence. The third group of organisers contains ‘general reference’ to ‘anti-vax’ actors or protesters, individual and anonymous actors, that contrarily to past waves of RR mobilisation (e.g. Caiani and Parenti 2013) emerge as particularly active during the Covid related protests (Fig. 3).

‘Cultural right-wing groups’ have initiated anti-vax protest events to a smaller extent, in both countries, and include religious associations, parents’ groups mobilising on the basis of conservative values as well as neo-fascist/neo-Nazi groups or activists on anti-vax. Examples include the motorcycle clubs in Hungary, the parents’ associations protesting against vaccines based on traditional values (e.g. ‘Giu le mani dai bambini’Footnote 22), and Catholic ultra-traditionalist organisations (such as Militia Christi in Italy). However, there are also many RR individual activists among the anti-vax protest organisers, as explained by one Hungarian core activist, mobilising also on the basis of traditional and new RR conspiracy theories (including the argument that ‘COVID-19 was created and intentionally released by the Illuminati-Masonic network in order to reduce the population’.Footnote 23 In the RR milieu, in both countries, freemasonry is an anti-Semitic trope. Finally, in the category ‘other’, we grouped those protest events initiated by single-issue groups, such as commercial organisations mobilised in the anti-vax protest, and the restaurant owners’ protests that were prevalent in both Italy and Hungary.

Looking at the specific action strategies adopted in the recent anti-vax mobilisations of the radical right, we indeed observe that (Fig. 4), first of all, right-wing groups have a variegated repertoire of action, made up of conventional, demonstrative, expressive, confrontational, and violent (including both mild violence and heavy violence) actions.Footnote 24 Secondly, right-wing action strategies vary a lot from one country to another.Footnote 25 We can indeed detect significant differences between the two countries in the tactics chosen by the collective actors to express their claims.

In particular, both countries’ demonstrations are the most recurring form of action (accounting for 59% of protest events between 2021 and 2022, of which 47% in Italy vs 69% in Hungary). As regards confrontational actions, violence is more prevalent in ItalyFootnote 26 (where political movements and single ‘lone wolf’ activists were prominent in the anti-vax protest), while Hungarian protests (mainly dominated by RR political parties) rely much more on the least radical forms of action, i.e. conventional actions, used in 13% of cases in the country.

Violent anti-vax actions range from acts of ‘light’ violence against people or things, such as, for example, insults or threats against parliamentarians and politicians supporting the green pass; graffiti or slogans against vaccines and/or lockdown measures (such as the graffiti against leftist Unions, 6th June 2022, Palermo); speeches inciting people to violence; to acts of ‘heavy’ violence, such as assaults against political adversaries (e.g. the destruction of some Italian political parties Gazebos during the anti-vax paradesFootnote 27); attacks against offices of political opponents or journalistsFootnote 28; but also clashes with the police during the protest events (e.g. 28th August 2021, Naples, 23th October 2021, Milan).

Examples of demonstrative actionsFootnote 29 include the weekly demonstrations of activists against the green pass outside of town halls protesting against government restrictions on un-vaccinated people; the Students against the Green Pass protest against the Ministry of Education for the mandatory green pass in universities; or, the demonstrations carried out by local committees protesting against the closure of shops.

This further confirms for the radical right, as noted in social movement studies, the relationship between the type of organisation and tactic strategic choices in collective action, with more institutionalised actors more likely to use conventional forms of actions and informal groups more disruptive ones (Caiani and Parenti 2013). These findings, which are also in line with previous studies showing the comparatively low level of RR violent mobilisations in Hungary vs Italy (Pirro et al. 2021), are better explicated through our interviews, which comprehensively provide the reasons and impetus for various strategic action decisions by participants.

First of all, we find a relationship (predominantly in Italy) between the internal organisational structure of right-wing groups (horizontal vs. hierarchical) and the tactics selected, with hierarchy coupling with violence. For example, Forza Nuova, as a traditional Italian right-wing party with a very hierarchical organisational structure centred around the leader, justifies violence as a legitimate (and necessary) means of action to be used in the anti-vax protest too, as explained within, “in the radical right milieu, whoever fights more gets more attention and wins more supporters. FN is always on the front line and whenever we have to fight, we simply do it…” (IT.9). On the other hand, other Italian RR organisations mobilising in the anti-vax protest, such as Casa Pound and Movimento Nazionale, which internally have a “kind of inner democracy” (IT.10), all the while accepting violence in the main as a tool of protest,Footnote 30 give consideration to the ‘high costs’ of this strategic option: “We have to consider the costs of violence and its consequences especially after what happened to FN [i.e. the banning of the organisation after the violent attacks against the Unions]. Italians distance themselves from the overall movement and anti-vax protest and the reactions of the government was strong (…) the attack against the Unions gave the government an excuse to fight us” (IT.11). Finally, the Students against the Green Pass, a sizable part of the Italian right-wing anti-vax milieu, who, following horizontal decision making processes, tend to adopt expressive and conventional actions to underpin their demands, stress that “violence is useless, it’s not a solution to the problem” (IT.5), “we want to express our demands through speeches and peaceful protest” (IT.3).

Secondly, especially in Hungary, demonstrations remained non-violent, as the activists preferred peaceful means of protest in order not to undermine public opinion (HU.4), as well as avoiding any police response (“We don't want the police to punish anyone …, we didn't want any political repercussions”, HU.4).

Finally, we also found some tactical innovations (mostly in Italy) deployed by the RR during the protest. In order to ‘adapt and penetrate’ the broader anti-vax movement, RR organisations and activists participate in protests without their symbols (“we leave our flags behind”, IT.2); trying to use a less radical repertoire of contention (similar to Hungary) and, promote a strategy of ideological political neutrality, so as to recruit more people to their cause (protesting together with “ordinary” people is “our first aim”, IT.10). Finally, the perception of the high cost of violence in terms of ‘de-legitimisation’ of the movement, convinced the RR in Italy from homogeneously adopting violence as a strategy.

Radical right anti-vax mobilisation: issues and frames

A third type of explanation for collective action (beyond the context, and the type of organisation) link forms of action to situational characteristics, such as specific issues and targets, as well as interactions with different types of actors. This section will focus on issues, the next one on networks. Indeed, some scholars have suggested investigating extreme right mobilisation by observing its preferences for specific political arenas (i.e. topic of mobilisation) and argue that its emergence can be explained based on the different fields of issues. For example, Kriesi et al., (2008) have shown that opposing immigration and European integration (i.e. key issues linked to cultural and political globalisation) has become central for the current populist right’s programmatic offer.

In our study, when examining the main issuesFootnote 31 of which the Italian and Hungarian radical right mobilise in the anti-vax protest in recent times (Fig. 3), health was confirmed as a key issue of the current radical right (68% of anti-vax-related events), in spite of some country specificities. We see, indeed, that secondly political (15%) and socio-economic (19%) issues are prominent in Italy (accounting for almost one-third of all events registered), while Hungary health issues stand out (85% of events). Surprisingly, cultural issues in Hungary are almost absent, while in Italy they are significant (accounting for 16% of anti-vax protest events) and conducive for networking and overlapping between the radical right and other conservative movements mobilising in the anti-vax wave, such as religious and conspiracy-inspired groups (della Porta and Lavizzari 2023).

Along with contrasts, we also found commonalities between the two states. As transpired in the interviews, COVID-19-related demonstrations encompassed a melange of demands and interpretations of the COVID-19 crisis. Nonetheless, both countries follow similar paths in respect to frames and demands. The interviews carried out revealed the rationale and justification for the mobilisation (i.e. frames or ‘cognitive schemes’ making sense of external reality by collective actors, Caiani 2023) and some common RR frames were identified (and reportedly quite widespread) in the anti-vax ‘regressive’ camp in Italy and Hungary. As already noted for the progressive movements (della Porta 2022), new frames specific to the Covid crisis were built on existing frames, constructing overly comprehensive ‘master frames’ and a narrative resonating with new emerging knowledge.

Firstly, the two countries’ anti-vax activists have interpreted their campaign against the Green Pass as a battle for ‘freedom and liberty’. Most of the interviewed activists agreed that mandatory vaccination and the respective governmental measures restrict their freedom of choice, while some with a stronger view accuse the government of establishing a “sanitary dictatorship” (IT.1). Other activists have demanded more transparent decisions and information about vaccines and Covid tests or have criticised the government for restricting human rights (“We think that our freedoms are violated, (…) our fundamental human rights, our sacral rights, our right to a clean body”, HU.4; “government measures violate fundamental rules of the Italian Constitution” (IT.5).

Secondly, there is a broad claim of ‘discrimination (by the state) among citizens’, i.e. the un-vaccinated citizens “The Green Pass becomes a logic of absolute discrimination, people must be free to choose whether they want the vaccine or not” (IT.17). In that sense, anti-vax activists agreed with the idea that the restrictive measures imposed by national governments are not simply a response to the Covid crisis but are in fact the national governments’ strategic plan to impose social control over civil liberties. In this sense, and thirdly, traditional ‘conspiracy theories’ are re-mobilised. Activists (HU.2, HU.3 and HU.6) claim that the pandemic is a part of a plot by global elites to establish a ‘New World Order’ (“In my opinion, Covid is all about only one thing, how we can turn everyone into an even better slave”, HU.2), (“just a framework for controlling people” HU.6), and that ‘the Green Pass will be connected with a barcode and points system to be used for other purposes, beyond the health emergency’ (IT.5).

Networks in the anti-vax RR protest and ‘movements–parties’ relations

Social movement scholars have long since highlighted the importance of investigating collective action, so as to insert it into the broader ‘organisational field’, of which it is a product. Importantly, right-wing mobilisation does not happen in a vacuum, but in the interaction among social and political actors which extreme right groups refer to and whom they address (e.g. anti-racist groups, political institutions, other adversaries, but also potential ‘allies’ in power, della Porta 2012, p. 77). Moreover, social networks are the basis for movement recruitment and the path to popular mobilisation (Diani 2015), while grievances alone are not enough to create the mobilisation (Buechler 2000).

If we assess the RR anti-vax networks, we can see that Italian radical right organisations rarely organise protest events alone (see Table G in Appendix in Supplementary Material): roughly 20 per cent of registered events (31) are co-organised with one or more organisations within the broader anti-vax movement. They primarily include: single-issue groups and economic actors (for instance, the ‘Io apro’ association); other RR groups (e.g. CasaPound; the subcultural milieu of the right-wing soccer fans known as Ultras); right-wing politicians including local representatives of the Italian party Fratelli d’ Italia, Forza Nuova and Lega; as well as ‘unorganised and anonymous activists’ and youth organisations such as ‘students associations’. In contrast, Hungarian anti-vax protest events are mainly organised by a single actor, even if some right-wing groups, such as Our Homeland movement-party, have been particularly active in this respect, staging protests with some civil society organisations (such as the ‘Doctors for Clarity’ group or the ‘Libertarian’ “Cut the 75% of Taxes Party” (LA75) party.

Our interviews revealed that these horizontal networks are very important for reinforcing ‘the overall cohesion of the protest’ (IT.1), as well as the internal ties within the Italian RR organisational milieu (as testified by the collaboration between the National Movement and CasaPound Italia, IT.10). As explained, “the pandemic opened a new page for the Italian radical right (…). During the battle against governmental measures, our organisation started to broaden its connections with religious groups, incorporating the catholic movement Militia Christi (…). Actors that previously did not protest, are now on the streets with us and even during Covid, joined our organisation” (IT.10). As asserted “once the campaign against the governmental restrictions was launched, anti-vax activists created local committees in each city, in order to organise local weekly demonstrations and national protests” (IT.23). Those local committees created in turn “online groups on Facebook with the aim of recruiting new members and coordinating national actions” (IT.14) including previously non-politically active individuals who wanted to protest against the governmental measures (IT.10). We find a lot of overlapping membership between these committees, student organisations and small radical right groups (IT.5). During the anti-vax protest the limits between activists’ memberships became increasingly blurred.

In both cases, however, as emphasised in our interviews, these ties (horizontal and vertical) are reinforced during protest events (‘nurtured on the protest field’,Footnote 32 ‘in attempts to organise common actions’), which therefore work as ‘eventful protest’ (della Porta 2020), enhancing further the relational, cognitive and emotional resources for later protests—as it is explained, “we also created a common platform for the next national elections in four years from now” (IT.10). In this sense, the same protest events appear to function as spaces of political interaction between actors resulting in new potential coalitions (Van Dyke and Amos 2017), as, in Italy, was the case of the religious group Militia Christi with the radical right movement The National Movement of the National Patriots Network.

In spite of the allegedly close political opportunities of the context (see Sect. “Empirical analysis—political opportunities and RR anti-vax mobilisation: country and time” above), the protest events and the relationships created during them seem to act as ‘resources’ for the mobilisation. Indeed, although these protests tend not to affect the policies and have limited effect on the public (especially in Hungary), activists stress psychological changes associated with their activism. As explained by one Hungarian interviewee: “I get people closer to me, I’m not so distant, and my faith in God has also strengthened. And that’s important” (HU.1). The protests we organised “brought people together, the patriots of this county; my conscience is clear, and that’s the most important thing” (HU.6).

In Hungary, it is predominantly vertical networks that are built, and the addressees of the protest are generally the national institutions and political parties (in 90% of cases, tab 2A in Appendix in Supplementary Material). However, many actors also stress the need to cooperate extensively (horizontally) with other RR organisations in the country. For instance, much contact was made between right-wing actors and spiritual groups or single-issue groups who opposed government measures in the wake of the pandemic such as the Association of Owners of the Hungarian StateFootnote 33, which refutes the Hungarian constitution and organised alternative PoliceFootnote 34; as well as the civic organisation Doctors for clarity (see Table D in the Appendix in Supplementary Material for description) and the Our Homeland Movement party who are the most central figures within the field.

Movement–parties interactions are abundant, as our data have shown, albeit, at times ambiguously in nature between cooperation and conflict. In Italy, despite the official distance from the anti-vax movement taken by both right-wing parliamentarians of FdI and the Lega parties, some candidates (mainly at the local level) from both political parties were open towards the claims of the protesters and even supported their cause by participating in some protest events is a good case in point. Anti-vax activists perceive this type of indirect support from the institutional radical right as an ‘opportunistic strategy’, but they also firmly consider it an opportunity (“only radical right parties can be seen as our allies”, IT.5). Italian RR mainstream parties, on the other hand, appeared to purposefully follow a dual strategy in their political discourse: on the one hand supporting most of the government restrictions, on the other hand, at a personal ‘non-party’ level as ‘open’ toward the challengers. At the same time, radical right ‘movement-parties’ mobilising in the protest arena (such as Forza Nuova, Casa pound) believe that the mainstream ‘allies in power’ (i.e. in Parliament), in particular FDI, share the same agenda as them (as stressed “FdI has the same thinking as us”, IT.11; they “talk about our issues (…)” IT.9). In sum, many radical right interviewees feel that their demands can be voiced via radical right institutional parties because of an “established network of connections and communication channels” (ibid.). Nonetheless, the two spheres (street and institutions) remain divided.

In Hungary, contrastingly, the main right-wing movement-party ‘Our Homeland Movement’ (see the Appendix in Supplementary Material, Table D for description) has emerged as a prominent anti-vax actor in the street and works in close connection with the institutions. As explained by one Hungarian activist: “Basically, we distance ourselves from the parties; they do not work for us, so whichever way you look, they are pretending to be doing politics. But we have a relationship with Our Homeland Movement [party]” (HU.1). Activists in both countries perceive many of the parliamentary political parties as “enemies” of the movement, though they view a few of them differently. So, how can Our Homeland Movement party’s high prestige be explained among great scepticism of political parties in Hungary? It is a result of the country’s extreme political polarisation, where anti-vax activists do not want to cooperate with either the government/Fidesz or the opposition parties (“We have strictly banned political connections, so we have not allowed any political actors to participate in our events”, HU.4). Contrary to the mainstream parties, Our Homeland Movement party is seen as a new extra-parliamentary party outside of the “corrupt political elite”. Thus, it is considered trustworthy for issues such as anti-vaccination.Footnote 35

In the Hungarian case, therefore, there was cooperation only between the movement-parties (mostly the RR’Our Homeland Movement party’) and the civil organisations/movements. The mainstream parties in parliament have mostly ignored the anti-vax movement and their claims, while the democratic, liberal and left-wing opposition parties criticised the government’s measures restricting civil liberties (freedom of press, speech and assembly) and the expensive procurements. These parties have not shown any inclination to cooperate with the anti-vax movement.

Conclusion: pandemic, a similar ‘critical juncture’, two different outcomes of the movement–party mobilisation

Although the contemporary radical right is a diverse and multi-faceted phenomenon that influences both electoral and protest arena (Minkenberg 2019), shared insights between electoral and protest studies are still rare (McAdam and Tarrow 2010). Yet, the interconnectedness between political parties and social movements in the restructuring of political conflicts, especially in times of crises is increasingly pointed out (Hutter and Kriesi 2020; Borbáth et al. 2021).

In this study, we investigated the right-wing anti-vax protest comparatively as a social movement, focussing on the perceptions of the opportunities and constraints of the context by various types of actors (including movements and parties); the processual dynamics between the context and the protesters linked one another with various organisational and informal interrelations; and the broad repertoires of action and frames created by the actors themselves, as further resources for supporting the mobilisation.

Firstly, we found that grievances alone were insufficient to explain either the radical right mobilisation or its emerging features. Our study showed that radical right anti-vax protest is a notable and widespread phenomenon in the countries analysed; especially in Italy, which has also emerged as the country characterised by more favourable political opportunities, including a lively right-wing milieu. This also includes the capacity of the extreme right groups to mobilise a large number of people (mainly in the Italian case), which, although discontinuously in time and space, appears in our study to be on the rise as well. The patterns of mobilisation indicated that protests tend to correspond with shifts in contextual institutional opportunities and constraints. Protests intensify when government-imposed COVID-19 measures become stricter, and more radical when authorities respond less inclusively to the challengers, illustrating the complex dynamics of collective mobilisation. However, the intensity of anti-vax right-wing protest was higher than in Hungary, despite sharing similar pandemic-related grievances.

Secondly, it became evident that for understanding these mobilisations the existing political, societal and discursive opportunities of the country interact with the availability of organisational resources of the actors. Our analysis has pointed out that the main protagonist of the anti-vax protest differs in the two countries. Radical right parties play a prominent role in Hungary, whereas in Italy, social movements and individual right-wing activists are more active. Consequently, also the repertoire of collective action employed varies. In Hungary, where political parties are prominent, the movement tends to adopt a more moderate approach, utilising conventional and demonstrative actions. In contrast, Italy experienced a more radical form of protest, reaching violent peaks, characterised by the fluidity and movement-like nature of the demonstrations. This confirms the importance of the type of actors making strategic choices (della Porta 1995). Nevertheless, we can also relate the development of right-wing mobilisation and its forms (violent) to the organisational characteristics of the protesters, as our study emphasised that also the ‘symbolic and material’ resources linked to different organisational types (McCarthy and Zald 1977, della Porta 2012) seem to affect the mobilisation (and strategic choices) of right-wing groups, with Italian anti-vax protest being more disruptive.

Thirdly, to reach a full understanding of the development of radical right anti-vax protests it was necessary to explore their cognitive framing of them. Our research showed that, like other social movements, extreme right mobilisation is more likely to occur where political–discursive and cultural–discursive opportunities are more open (McAdam et al. 2001), like in Italy, for what concerns the presence of societal support (vs. the dismantled media independence and freedom as seen in Hungary). Also more specific context opportunities and circumstances (della Porta 2012), like historically rooted traditions as well as different salient issues and targets, can be referred to in order to understand some other features of right-wing mobilisation seen, as the higher orientation toward a socio-economic and political framing of the anti-vax protest in Italy. In this sense, the COVID-19 crisis has revealed and amplified shared grievances (Smith and Graham 2019) and successfully re-mobilised by the RR. In addition, the ‘paradox’ of the frequently recurring ‘libertarian frames’ (actually novel for the European right-wing tradition) in the analysed protest further indicated that radical right actors, in both the countries, have strategically changed their discourse to adapt it with the broader demands of the no-vax wave. Also research in non-European contexts confirm these findings, pointing out as the far-right is increasing placing emphasis on bodily freedom and personal choice rhetoric (Eslen-Ziya and Pehlivanli 2022).

Lastly, our study underlines the stark difference between how the (populist) radical right parties in Italy and Hungary respond to anti-Covid mobilisation, showing how political protest may sharpen the polarisation of party politics. Orban is an example of a populist leader (who, however, has not followed a denialist approach like Trump and Bolsonaro (Brubaker 2021); Italy, as a multi-populist country, has parties like the Lega and especially the M5S, who helped fuel the anti-vax view when in opposition, but abandoned the cause once in government. Similarly, our study highlighted the more nuanced yet important differences in responses by established Italian and Hungarian mainstream parties. These findings invite further investigation into the link between populism and anti-vax (in relation to the radical right), since also current studies on epistemic populism and conspiracy theories stress the broadening of discursive opportunities that elites might offer to protest politics on these topics (Eslen-Ziya and Giorgi 2022).

To sum up, although opposition to vaccination mandates is no new (Hussain et al. 2018), we argue that the pandemic offered new opportunities for the empowerment of (new and old) radical right collective actors, allowing for various interactions between movements and parties. Re-shaping in this way institutional politics and the protest arena as well. As seen, ‘movement-parties’ are more active and prevalent in Hungary, as the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary elections further demonstrated, with the entry into parliament of the (new) radical right-wing political party that had been prominent during the pandemic protests. In Italy, political movements and other radical right and conservative social movements (like radical Catholic ones) are, by contrast, the most significant anti-vax actors. When investigating the networks of the anti-vax mobilisation, with a special view on ‘movement–parties’ interactions, signals of a strict division of labour between the two sides are visible in Italy, while more collaborations (or sometimes indifference), as well as the consolidation of new actor (as the case of the movement–party formation Our Homeland party), characterises Hungary. The Italian anti-vax mobilisation is more adversarial towards vertical politics, investing more on horizontal networking within and beyond the right-wing milieu, while in Hungary vertial contacts with natioal institutions and (not mainstream) political parties are frequent (on horizontal vs. vertical ties by social movements see also Cinalli and Füglister 2008).

Οur study indicates that the pandemic acted as a critical juncture (della Porta 2022), significantly influencing the relationship between social movements, protest and institutional politics. It empowered certain new and established RR actors while disempowering others, resulting in different outcomes, as we summarise in Table/Fig. 3a in Supplementary Material.

In both cases the no vax protest represented an occasion for the RR to make new recruits (as first time protesters) and re-mobilise usual RR activicts and groups, however, in terms of Movement–parties interactions, while in Italy RR political parties (also in power) are not aligned with the anti-vax mobilisation and claims; in Hugary while mainstream parties mostly ignore the anti-vax movement and issues (even the liberal and left-wing opposition criticising the government’s measures), some other parties own the Anti-vax issue, and co-opt and cooperate with the movement (before entering the Parliament).

We argue that using the lens of movement-parties, as well as other traditional theories of social movement studies, might offer valuable insights into the causes (and consequences) of radical right mobilisation in the protest arena, as well as more broadly into the understanding of radical right politics in the 21th, characterised by increasing interactions and fluidity between these groups (Busher 2015; Caiani and Cisar 2018; Hadj Abdou and Rosenberger 2019; Nissen 2020; Pirro and Gattinara 2018; Pirro et al. 2021). Focussing on the interactions between electoral and protest politics seems especially important for studying the segments of the population that tend to express their grievances not through street protest, but through the protest vote, which is more common among people siding with the radical right than it is among movements on the political left (Hutter 2014).

Movement-parties appear to be of particular scholarly (and social) relevance today in a ‘Europe in crisis mode’ (i.e. Covid, the Ukraine crisis), which has seen only moderate policy response from the political mainstream. Throughout the world, we can see street mobilisations turning into new political parties (such as Jobbik) and vice versa, i.e. established political figures spawning political mobilisations (Tea Party movement, FIDESZ). Beyond our study, limited in scope and time, we can identify various other ‘movement parties’ that have mobilised on the (radical) right in Europe. We can even find (self-proclaimed) movement parties that have successfully connected mainstream and extreme variants of right-wing ideology, as is the case of various Eastern European countries (as showed by other contributions in this special issue, but also, Herman 2016; Císař and Štětka 2016; Císař 2017).

Data availability

The dataset is available from the corresponding author, Manuela Caiani, upon reasonable request.

Notes

Acknowledging the complexity of the terminological debate, which is beyond the scope of this article to address in detail, we use the term radical right to refer to those groups that exhibit in their common ideological cores the characteristics of nationalism, xenophobia (ethno-nationalist xenophobia), anti-establishment critiques and socio-cultural authoritarianism (law and order, family values) (Mudde 2019). This deliberately includes political party and non-party organisations, even subcultural violent groups as well as cultural associations and think tanks. Other scholars, prefer to use a broad and inclusive meaning of the ‘far-right’ category, which encompasses other labels commonly used in the literature such as ‘radical right’ or ‘populist radical right’ (Wondreys and Mudde 2022).

According to the ‘transformative approach’ (Hilgers 2005), a social movement might evolve into a political party, attracting voters.

Namely, the set of opportunities and constraints that are offered by the institutional structure and political culture of the political system in which these groups operate (Tarrow 1994; Koopmans 2005). The concept came about primarily looking at the degree of ‘closure/openness’ of a political system (e.g. in terms of electoral system, degree of centralisation, configuration of power between allies and opponents, etc.) Furthermore, it is formed in terms of more inclusive or exclusive cultural contexts vis-à-vis the challengers (e.g. the political culture of the elites and the way collective action is managed by authorities).

The mortality rate in Hungary was more than one and a half times higher than in Italy (505 deaths per 100,000 VS 311 in Italy); https://COVID-19virus.jhu.edu/data/mortality.

In terms of organisational milieu the RR in Italy is a complex galaxy of organisations (including political parties, ‘movement-parties’ and social movements, with subcultural and juvenile groups, conservative and catholic organisations), although sometimes divided by ideological diatribes (Caiani and Parenti 2013). In Hungary, the RR milieu is less developed than in Italy or in other Western European countries (Caiani and Susánszky 2020). We can find the same types of actors (parties, movements, subcultural groups etc.) as in Italy, albeit with fewer supporters and members, and thus, with less mobilisation potential.

Despite its limitations (media selection bias), PEA allows for systematisation and assessment of collective action (Hutter 2014).

In Hungary we used the Hungarian Protest Event Database—HPED (https://openarchive.tk.mta.hu/599/). The dataset relies on the official records of the police on registered demonstrations. For the analysis, we filtered out (1) the cancelled demonstrations, (2) the incorrectly reported events (e.g. religious mass procession, private events), and finally, (3) the party campaign events (e.g. disseminating party campaign materials. The dataset references the protest events’ issue, organiser, the place and time.

Although the intersection between radical right actors and the regressive side of anti-vax protests has been underlined by many works (e.g. della Porta and Lavizari 2022; Wondreys and Mudde 2022); it is important to recognise that not all anti-vax protests are exlusively driven by the RR. In fact these movements have been multi-faceted, representing a cross-section of society (Gerbaudo 2020). In our protest event analysis and interviews we focus only on events organised (or co organised) by radical right actors in the two countries and leaders or activists of self- defined radical right organisations as interview partners (for details on the newspaper articles retrival and relevant’protest events’, as well as on interview partners recruitment, see respectively tables A, C and D in the appendix in Supplementary Material).

Articles were coded by two independent coders into ten variables.

The interviews were conducted mainly in person from January 2021 to June 2022. To reach right–wing activists, we used snow ball techniques and positional methods. Gaining access to the field was challenging, but we managed to overcome difficulties by following the instructions of previous research on the topic (Blee 2003). The interview partners were variably selected by age, gender, group, their role in the movements (either organiser/founder or member), and geography (urban/rural or periphery).

We included a few ‘expert interviews’ in both cases (i.e. journalists, academic professors, chief of police, etc.).

To a greater extent in Italy, vis-a-vis grievances conducive to the emergence of protest in both countries.

Similarly, it was found that the anti-vax protest tends to proceed though peaks and cycles, often linked to an institutional decision on the pandemic.

Further, the mass media are understood to be changing their attitudes vis-a-vis the anti-vax movement over time (i.e. more favourable in the central months of the given timeframe, as noted in the intensity of the protest based on our PEA). As underlined by one activist, “now they leave us talk a bit, although we are still criticized…” (IT 3).

In the case of Covid related protests, we can see important differences among the different media sources. While the government-critical media covered every fourth demonstration, pro-government media and public media reported about only 8 and 1 percent of the events. This is also confirmed by previous studies, indicating media biases regarding protest events in contemporary ‘illiberal’ Hungary (Susánszky et al. 2022): government-leaning media use discrediting frames depicting protesters and protest events as insignificant, negligible, or violent.

“Before the demonstrations, we used to contact various media in order for the demonstrations to be covered, …however they usually reject us” (HU.4).

For the classification of the radical right organisations and anti-vax protesters initiating the events, we followed (Caiani et al. 2012) and the most diffused classification of the RR used in protest event analysis of its mobilisation (see also Castelli Gattinara et al 2022). Radical right ‘parties’ (or specifically ‘movement-parties’ such as the Italian Forza Nuova and Casa Pound) are those groups which define themselves as such and participate in elections. In the category ‘political movements’, we included groups that openly take part in political activities, without participating in elections. We also included youth organisations close to the ER (e.g. ‘Students against Green pass’, https://www.studenticontroilgreenpass.it/.), RR magazines and media, as well as new actors such as the various Committees and coordinating networks against green pass/vaccines emerging in the wake of the COVID-19 protest such as ‘Napoli no Green Pass’, ‘Comitato Libera scelta’, and ‘No Green Pass Trieste’. Within the category ‘cultural conservative organisations’ we grouped traditional cultural RR organisations (for example, the ‘Associazione Nazionale Arditi d'Italia’ https://arditiditalia.com/), and the Catholic ultra-traditionalist organisations, such as Militia Christi), as well as Identitarian RR and groups, and some parents’ groups mobilising nt he basis of conservative issues and values. The category ‘generic ref./individual/anonymous’ is a generic reference to RR groups and individuals or anonymous RR actors as initiators of the protest event. Finally, in the category ‘other’ we grouped: single-issue groups (e.g. organisations fighting against vaccines and government measures on the basis of juridical-civil-individual rights—such as ‘Romagna Costituzionale’, and ‘Dubbi e Precauzione’, https://generazionifuture.org/dupre/, Emilia Romagna FB page), as well as economic groups which mobilised together the RR anti-vax movement, on the basis of instrumental – economic reasons on the heterogeneity of anti-vax protest actors even beyond the RR (see also della Porta and Lavizzari 2022).

In order to classify different forms of action, we grouped the strategies that emerged from the analysis of protest events into six categories. The category ‘conventional actions’ includes those political actions associated with conventional politics (e.g. organising press conferences, distributing releases, organising electoral campaigns, etc.). The category ‘demonstrative actions’ includes actions intended to mobilise large numbers of people (e.g. rallies, petitions, street demonstrations). The category ‘expressive actions’ includes actions mainly directed (internally) towards the members of the group, in order to reinforce the in-group cohesion and identity (e.g. commemorations, cultural events, etc.). The category ‘confrontational’ includes actions which are non-violent, but usually illegal, the aim being to disrupt official policies or institutions. Moreover, the ‘violent actions’ category includes those events that imply some form of physical violence (e.g. violent clashes with political adversaries or the police, etc.). For this classification see Caiani et al. (2012). Finally, the category ‘online’ action includes online events by right-wing groups reported in the press.

This is also confirmed by a high and significant Cramer’s V Coefficient between ‘action form’ and ‘country’ (0.45***).

The proportion of unconventional forms of action (e.g. clashes with police, inciting violence in a press release) is almost three times as high as it is in Hungary (42% vs. 15%).

Against Forza Italia on the 24th July 2021, Pescara; against the 5SM on the 28th August 2021, Milan.

E.g. on the 11th September 2021 in Milan; against the Newspaper, La Nazione on the 7th August 2021, Florence.

Instances of marches, rallies, street protests or petitions (such as the anti-government and parliament mobilisations in several Italian cities against compulsory vaccination for citizens over 50 (e.g. on the 8th January 2022, Turin); against the healthcare system and government health policies (e.g. 28th July 2021, Rome; 8th January 2022, in Bologna); against the government’s and the pope’s positions on vaccines (e.g. 25th September 2021, Rome); the various ‘no green pass’ strikes (e.g. on the 11th November 2021, Turin); the demonstrations against the health agency AIFA (e.g. 1st of August 2021, Rome); demonstrations in front of symbolic places like the Town Hall of the Capital, the main train station (16th January 2022); the various ‘no green pass’ parades (e.g. 15th October 2021, in many cities such as Turin, Messina or Florence); the sit-in (e.g. 13th November 2021, Milan); ‘no green pass’ torchlight marches (e.g. 28th July 2021, Turin, Rome), as well as the ‘no green pass’ and pro Putin parade (2nd April 2022, Modena); the 'no green pass’ strikes (11th November 2021, Turin; 15th October 2021, Genoa).

E.g. as one activist commented, “we are the ones with the military presence so we know how to be respected and sometimes we need some weapons…” (IT.10).

In our analysis, we classified the various issues of radical right mobilisation into six categories (see also Caiani et al. 2012): ‘health issues’ related to COVID-19; ‘social and economic issues’, which includes all events related to the social and economic consequences of the COVID-19 regulations (e.g. schools and economic activities’ lockdown measures, etc.); ‘political issues’ which includes events related to political life and the COVID-19 governance in the country (e.g. decisions on vaccines, green pass); ‘conservative values’, which includes all anti-lockdown/green pass/masks/anti-vax protest events related to conservative values and issues (e.g. religious, law and order, family); ‘life of radical right organisations’, which refers to events related to the internal life of the radical right milieu (e.g. stigmatisation of the ER and anti-vax protest; radical right groups and strategies, relations with the judiciary, etc.). ‘Globalisation and European integration’, which entails COVID-19 issues and supranational politics (e.g. regulations and the EU, etc.) but also events focussed on the pandemic and neoliberal globalisation and/or its presumed principal promoters (including the G8, WTO); ‘migration&nation’, which includes all events giving a perspective on the COVID-19 protest as regard immigration and/or nationalism (import of the virus from abroad; security, economic and cultural situation of immigrants vs. Italians amid the pandemic in the country, etc.).

After the first protests, “a WhatsApp chat group was created, among leaders of various radical right Italian organisations, designed to organise and hold offline meetings to coordinate anti-government actions” (IT.14).

magyar-allam-tulajdonosai.com.

This cooperative party-movement nexus, however, changed after the parliamentary elections in April 2022, as recognised by some activists, a trend toward moderation of the party in institutions. As the Our Homeland Movement party activist explains, “[If an organisation] contacts us to organize a crowd for their demonstration and generate media appearances, it’s double-edged, …because now that we are a parliamentary party, we have to be more careful than when we were just a movement party on the street” (HU.2).

References

Batory, A. 2022. More power, less support: The Fidesz government and the COVID-19virus pandemic in Hungary. Government and Opposition, 1–17.

Bene, M., and Z. Boda. 2021. Hungary: Crisis as usual—populist governance and the pandemic. In Populism and the politicization of the COVID-19-19 crisis in Europe, 87–100. Cham: Springer.

Blee, K.M. 2003. Inside organised racism: Women in the hate movement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Borbáth, E., S. Hunger, S. Hutter, and I.E. Oana. 2021. Civic and political engagement during the multifaceted COVID-19-19 crisis. Swiss Political Science Review 27 (2): 311–324.

Brooks, S.K., R.K. Webster, L.E. Smith, L. Woodland, S. Wessely, N. Greenberg, and G.J. Rubin. 2020. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet 395 (10227): 912–920.

Brubaker, R. 2021. Paradoxes of populism during the pandemic. Thesis Eleven 164 (1): 73–87.

Buechler, S.M. 2000. Social movements in advanced capitalism: The political economy and cultural construction of social activism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Busher, J. 2015. The making of anti-Muslim protest: Grassroots activism in the English Defence League. London: Routledge.

Caiani, M., D. della Porta, and C. Wagemann. 2012. Mobilizing on the extreme right: Germany, Italy, and the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caiani, M. 2023. Framing and social movements. Discourse Studies 25 (2): 195–209.

Caiani, M., and O. Císař, eds. 2018. Radical right movement parties in Europe. London: Routledge.

Caiani, M., and L. Parenti. 2013. European and American Extreme Right Groups and the Internet. London: Ashgate.

Caiani, M., and P. Susánszky. 2020. Radical-right political activism on the web and the challenge for European democracy: A perspective from Eastern and Central Europe. In Democracy and fake news, 173–187. London: Routledge.

Castelli Gattinara, P., C. Froio, and A.L. Pirro. 2022. Far-right protest mobilisation in Europe: Grievances, opportunities and resources. European Journal of Political Research 61 (4): 1019–1041.

Cerqua, A., and R. Di Stefano. 2022. When did coronavirus arrive in Europe? Statistical Methods & Applications 31 (1): 181–195.