Abstract

As a way to manage political disagreements over public policies, political representatives might be tempted to avoid open discussions by depoliticising political issues—hoping that the conflict may eventually disappear. When decision-makers employ such strategies, it is up to the administration to make political priorities and manage unresolved policy conflicts. Earlier studies indicate that there are at least two strategies that administrators can employ to manage such ambiguities: (re)framing and technical depoliticisation. This article reveals that public administrators also employ a third framing strategy: repoliticisation, where administrators seek to endow their policy areas with political power by connecting politicians to the work and implementation of policies. The study is based on 38 interviews from 11 municipalities in Sweden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As a way to manage political disagreement over public policies, avoid blame and responsibility, and shy away from lengthy processes riddled with conflicts, policymakers might be tempted to disengage from discussions by depoliticising political issues. This can be done by reducing decisions to technical matters best handled by professionals (Chech 2013), or to agree on loosely formulated goals on which everyone can agree and delegate the issue to the administration, hoping that the conflict may eventually disappear. An example is when politicians from opposing camps agree on political goals stating that their city/municipality is to be inclusive, safe, and sustainable. A goal that is simultaneously difficult to be in opposition with and unclear as to what it means. This could be part of a ‘blame game’ where politicians seek to take credit and shift blame from voters (Hood 2002). When political decision-makers employ such strategies, it creates an ambiguous situation where administrators endeavour to interpret how to implement policies and make political priorities (Lipsky 1980), a responsibility that traditionally belong to democratically elected leaders. Depoliticised conflicts are here characterised by situations where existing political disagreements on issues are left unacknowledged or unresolved at political level and instead delegated to the administration.

The power dynamic between politicians and administrators is complex. While politicians are leaders and accountable to their voters for every action undertaken by their administration, they are dependent on the administrations will and ability to implement policies. This is in line with institutional depoliticisation, which refers to a formal principal-agent relationship in which the elected politician (the principal) sets wide-ranging boundaries for policies, while the administrator appointed (the agent) is in charge of the day-to-day operational management of the issue in question—within the framework set by the politicians (Flinders and Buller 2006, p. 298). Political and administrative levels are commonly separated by organisational boundaries when governmental organisations are designed. As organisational boundaries are normative, constituting rules and roles specifying who is expected to do what and how (Scott 1981), this separation shape the rules for how political conflicts are to be managed (Skoog 2021). Accordingly, delegation of responsibilities for political issues, i.e., decisions on ideas and policies that is the focus of political parties, from politicians to administrators has consequences for politicisation and how political an issue is perceived to be. The term ‘administrative level’ is here used to generally refer to the administrators who together populate the administrative arena.

This rationale is in line with the management-by-objectives doctrine favoured by advocates of New Public Management as a way to separate politics and administration (Bäck 2003). Proponents argue that placing issues at one remove from the conventional political arena is a way to shield the agent from short-term political considerations such as vote seeking and populism. Critics, on the other hand, argue that giving more responsibility to managers and turning more issues into technical matters, rather than ideological ones, might lead to a decrease in the capacity of politicians to execute policies by setting directions and intervening (Maor 1999). It can thus be argued that depoliticisation is part of a managerialist approach to governance.

The question of whether an issue should be considered political is at the heart of the relationship between politicians and administrators. While we know from earlier studies that administrators can shape and influence political decisions and implementation (see ex, Blom-Hansen et al. 2021), a classic assumption is that politicians should handle political matters and administrators and experts that should handle non-political issues (e.g. Rosenbloom 1983; Simon 1946).

However, it is frequently argued that the separation of roles is merely an ideal-type, and that in reality the roles and tasks allocated between politicians and administrators are complementary rather than oppositional (Svara 2006). There are also indications that public managers become politically astute in relation to the political will, rather than infringe on the political arena (Hartley et al. 2015; van Dorp and t’Hart 2019). There has even been a call for public administrators to act entrepreneurially (Moore 2014), which has been discussed in terms of the risk of democratic usurpation (Rhodes and Wanna 2007). This debate thus focuses on whether or not it is appropriate for public administrators to be involved in political matters and in what way they do so.

We argue that, rather than focusing on whether public administrators should be involved in political matters, we need to examine how issues come to be labelled as political or non-political by politicians and administrators. Additionally, as scholars within the field of public administration tend to neglect the role of conflicts (Lan 1997), little data is available regarding what strategies the administration has developed to manage unresolved policy conflicts which end up in the administrative arena via depoliticisation. If it is true that public administrators can take over responsibilities for political issues (Svensson 2018), we need to learn more about how they manage these issues, and study the relationship between politicians and administrators, while paying special attention to the process in which issues are framed as political or non-political, i.e. (de)politicisation. The aim is to broaden knowledge and understanding of how unresolved policy conflicts are managed in the political-administrative system at local level. In this article we investigate: Which strategies are developed at the administrative level to manage depoliticised political conflicts?

Swedish municipalities represent a suitable context in which to explore the tension between political conflicts and depoliticisation. In international comparisons, Sweden has large municipalities with extensive political responsibilities for welfare services (Sellers et al. 2020). Additionally, the interplay between politics and administration in Swedish local government is great. The combination of these two factors provides an appropriate context for a study with a research aim such as ours. The empirical focus is on cross-sector strategists. The study is based on 38 interviews with politicians and administrators from 11 municipalities at local level in Sweden.

Depoliticisation and administrative strategies

Conflicts in this study refer to situations where there are difficulties in reconciling different interests or disagreements over policies or objectives (Schmidt and Kochan 1972; Skoog 2019; Skoog and Karlsson 2022). Earlier scholars have studied depoliticisation from a wide range of perspectives (Etherington and Jones 2018; Evans and Tilley 2012; Hay 2007; Mouffe 2005; Wolf and Van Dooren 2018). Common themes regard the role and power of a dominant rationale, shifts in political reasoning, the reallocation of functions and responsibilities to independent bodies or panels of experts, and the exclusion of politics through the adoption of “rational” practices. It is often argued that depoliticisation serves the purpose of shielding politicians and their choices from critique and accountability. Burnham defines depoliticisation as “the process of placing at one remove the political character of decision-making” (2001, p. 128). Here, depoliticisation entail a shifting of arena, or delegation, away from being part of the day-to-day work of politicians towards the administrative arena—a less obviously politicised arena (Strøm et al. 2003). However, creating a dichotomy between politicisation and depoliticisation risks oversimplifying a complex relationship (Blinder 1997). It is here regarded as a matter of degree, not separate entities.

Public administrators at all levels experience ambiguity and cross-pressures to a varying extent and often adopt strategies, or coping mechanisms, to ease their pressure (Lipsky 1980; Svensson 2018). If they did not do this, their situation would be psychologically exhausting with never-ending demands (Nielsen 2006, pp. 864–866; Winter and Nielsen 2008, 128ff). Lipsky argued that such strategies are so common that they might lead policy implementation astray (Lipsky 1980), signalling that it has the potential to be relevant to several types of public administrators. We argue that managing depoliticised conflicts where loosely formulated goals at the political level mean that little guidance is provided to administrators as to what output is expected from their work, constitutes an ambiguity where it is likely that administrators develop coping mechanisms to facilitate a manageable work environment. There are several potential strategies actors can employ as coping mechanisms, such as timing and seeking support from civil society to bolster their work. Based in a tradition of interpretative policy analysis, politics consists of framing and deliberations. Meaning that actors use frames to steer perceptions of others and to understand a policy themselves (see ex Hajer and Wagenaar 2003). Thus, framing means to highlight certain aspects of a situation and tone down others, meaning that there are several ways a situation can be understood (Knaggård, 2016). Below we present two framing-strategies that previous studies have suggested are of relevance for the interplay between political representatives and administrators. Our hope in this study is that they also are of relevance for studying how depoliticisation is managed.

First, one strategic quality is the ability to frame a vision or idea at the right time and in the right place in a way that attracts the attention of key decision-makers (Chong and Druckman 2007; Hysing 2014; Olsson 2009). While some argue that it is a certain type of political actors that perform such actions, so called policy entrepreneurs (Kingdon 1984/1995), and who take advantage of opportunities in order to influence policy outcomes (Cairney 2018; Mintrom and Luetjens 2017; Mintrom and Norman 2009), administrators across the public sector can use such actions as a strategy, indicating that public administrators can sense or anticipate in which direction the political winds are blowing (Bengtsson 2012; Niemann 2013) and then use their sensibilities to frame a policy from one sector to another, thereby increasing the likelihood of it being adopted. Additionally, a sense of timing is crucial for this strategy to be successful; i.e., the ability to perceive and take advantage of windows of opportunity is required (Kingdon 1984/1995). The first strategy is thus to (re)frame issues from one policy sector to another.

Second, one strategy to depoliticise conflicts is to frame or construct an issue as having a single correct solution, i.e., technical depoliticisation. This strategy has also been labelled ‘preference-shaping’ (Flinders and Buller 2006) or ‘discursive (de)politicization’ (Wood and Flinders 2014). It entails discursive claims where political choice is downplayed and normative policy choices are presented as neutral expert opinions—i.e., ‘rational’ and technically correct (e.g. Chech 2013). Whereby anyone who disagrees are labelled ‘irrational’. While this tactic may demand a high level of political capital, the advantage is that little structural or legal resources are required (Flinders and Buller 2006). Earlier studies indicate that although tendencies towards depoliticisation can be found in practically every political issue, there are some issues that are more likely to be depoliticised. These are issues with a high degree of valence (positive as well as negative) (Cox and Béland 2013), or that are made more easily into technical matters that can, and should, be disconnected from political concerns (Chech 2013). This approach is a frame employed by politicians as a convincing approach in relation to a policy choice. However, in this study we investigate whether administrators also use this strategy as a way to convince both politicians and senior managers that their approach towards a specific policy problem is the only feasible alternative.

Both frames are dependent on the use of language, where actors use words to tilt how issues are perceived by others. In this context, we argue that (re)framing means to tilt an issue from one policy field to another—with the aim of not stepping into a potential political conflict. While technical depoliticisation means to frame issues as lacking political aspects by presenting them as a neutral and technical exercise. We will use these two strategies found in earlier studies as a guide when interpreting our empirical data. We will remain open to the possibility of uncovering new strategies, or coping mechanisms, that administrators have developed to manage depoliticised conflicts.

Research design and method

To explore depoliticisation and politicisation, we need to identify organizations where both options can occur. Local governments in Sweden are self-governing units with major political responsibility for welfare services, and ability to set their own political agendas and tax-rates (Sellers et al. 2020). Accordingly, Swedish municipalities are not mere implementers of political decisions made at national level; they are self-governing units with the ability to set their own political agendas. The high level of interplay between politics and administration in Swedish local governments, coupled with the fact that municipalities have extensive political responsibilities, provides an appropriate context for a study with a research aim such as ours, where the focus is on how the political-administrative system manages unresolved policy conflicts. Swedish municipalities thus hold methodological advantages and provide the possibility of generalising results to similar contexts.

We argue that the likelihood that depoliticisation will occur is highest in policy areas characterised by (1) strong normative acceptance (Cox and Béland 2013); (2) a high level of ambiguity regarding definition and interpretation (e.g., Carstensen and Schmidt 2015; Seabrooke and Wigan 2016); and (3) a multitude of stakeholders and sectors both inside and outside the political-administrative organisation. Such policy areas are often characterised by being defined as complex or “wicked” and in the need of collaboration, coordination, and policy integration (Svensson 2020; Christensen et al. 2019; Molenveld et al. 2020). Common examples are sustainability, human rights, equality, security, and economic growth. These characteristics enable political issues to be transformed into technical matters or to be expressed in ambiguous terms due to the uncomfortable and politically ungrateful task of addressing them as conflicts. Which might open for situations where the administration needs to develop strategies on how to manage unresolved policy conflicts. We focused our efforts on policy areas with the traits described above.

38 interviews in 11 municipalities were conducted with: leading local politicians (8), chief executive officers (CEO) (3) and cross-sector strategists (administrators who coordinate the work within in policy areas such as sustainability, equality, children’s rights, security, etc.) (27). The empirical emphasis on cross-sector strategists is due to the fact that they are critical actors for the interplay between the political and administrative level: they are administrators but hold positions that are placed close to the political level. Their work makes them responsible for administrative efforts on issues which have high potential for conflict.

The included municipalities represent urban and rural areas with populations ranging from 15,000 to 140,000 with: 3 small, 4 medium sized and 4 large municipalities. We included variations in political majority: 4 governed by left wing parties, 6 by centre/right parties, and 1 by a broad coalition of parties. We strived to avoid cases known for having an unusually high/low degree of conflicts, and to include cases that were as average as possible. The variation in size does not appear to affect the outcome in any crucial areas; on the contrary, we argue that the patterns we distinguish across these municipalities strengthen our claims. The same goes for the political majority; the patterns are similar across the municipalities regardless of political majority.

The interviews were semi-structured in nature, meaning that some of the questions and themes were predetermined, but it was possible to ask supplementary and follow-up questions. A basic interview guide with questions based on themes and topics generated from the theoretical framework was used. This meant that we asked questions regarding the relationship between politics and administration, how it was determined whether a question was the responsibility of political representatives or administrators, etc. The data has been analysed by thematically grouping the strategies used to manage depoliticisation.

Administrative strategies to manage depoliticised conflicts

In this section, we present findings from the interviews. The presentation starts with a description of the consequences of depoliticisation as perceived by the interviewees. This will contextualise the findings and illustrate potential challenges administrators face regarding depoliticisation. We then discuss aspects of, and strategies to cope with, depoliticisation; (re)framing, technical depoliticisation, and getting the attention of politicians. The division into sections constitutes categorisations based on the theoretical expectations presented in Sect. 2 and on findings from the interviews.

Consequences of depoliticisation

A theme in the interviews is the consequences of being handed policies with loosely formulated political goals, i.e., a characteristic of a depoliticised political conflict, and on paper given a great deal of discretion with regards to formulating what is to be done and within what time frame. Below, an administrator reflects on what this means:

R: On the surface, there seems to be a very extensive level of discretion. However, if it is to have any effect, it is actually quite limited. Because I can’t do it myself. I constantly need to base it on having others who pick up [the slack], others who take initiatives and who do their share. So, it is actually very limited if you are to wait for [the municipal leadership] to figure out that this is what we want and what we should do.

I: Does the fact that there is no clear definition of what you should do have any effect on the level of discretion?

R: Yes, it is very limiting. (…) You can sit there and be a pen pusher forever, but if your issue doesn’t come up, you become a hostage.

(Diversity strategist 1)

As highlighted by the quote, the extensive level of discretion is often accompanied by a lack of resources and a weak mandate in the organisation, creating a complex situation where it is difficult to get others in the organisation to assist with implementation of policies. A manager elaborates on this:

Everyone says this is important, but no one wants to share their own budget to finance it. There is an interest both from the administration and from politicians, but when it comes to the crunch, we often hear “Well, we have to spend one full pre-school teacher’s salary on this”, so that is why we cannot do it. It is the constant fight over scarce resources.

(Manager, Department for Development 1)

The necessity to make priorities is pointed out by administrators who highlight the problem of having vague goals for policy areas. To avoid vague political goals, political decision-makers must position themselves politically and make strategic priorities accordingly. Which politicians at times avoid doing. Below, a strategist describes the endeavour to bring activities within their policy area as close to the annual report for the whole municipal organisation as possible. This respondent is working on a “welfare balance sheet”, which is to serve as a source of information for making strategic political decisions on specifically equality and equity. However, as the respondent belongs to a political sub-unit, the welfare balance sheet ends up not becoming the political product it could be at the central municipal level:

I have tried to bring the ‘welfare balance sheet’ as close as I can to the annual report, to use it in the budget, that is, to set the direction of the goals based on the result. And public health funding has also been assigned, which has a bearing on the direction of these goals. But now I can’t get any further. There are several reasons for this, but the main reason is really that we are placed here. That I am placed here.

(Public Health strategist 4)

Even though the administrator has received some funding, and thus has had some success, it is now not possible to do much more. This means that when issues are delegated to the administration, the broad discretion that having loosely formulated goals entails becomes problematic when there are few resources or incentives given that would encourage others to support their work. In the above case, the problem is also related to political ownership. On paper, the welfare balance sheet is a product of the entire municipality. But delegating it away from politicians to the administrators, and locating it in a sub-unit, means that it is not considered a product of the entire municipality, but of that sub-unit. Which signals the low political support for the policy in question.

(Re)framing

Depoliticised issues are considered the task of the administration but developing them might still require resources and support. When a depoliticised issue needs political support, the situation is often managed through framing and reframing, which means that administrators try to position a certain issue under the label of another policy or policy area. In the quote below, a cross-sector strategist describes how they manage such a situation within equal health:

Equal living conditions are a very difficult concept for the political centre-right. Traditionally, it is the left-wing that has worked with this, for example with The Spirit Level.Footnote 1 That is why, perhaps I shouldn’t say it, but you can try to temper things. Not talk about equality too much, but rather say that there should be equal preconditions. You use different concepts, but you are still referring to the same thing. Because at the end of the day, the centre-right doesn’t want unequal conditions either, but you might need to call it something else.

(Public Health strategist 3)

The difficulty in attracting attention within the organisation can be due to lack of interest or, more commonly, that the concepts that are associated with a policy area are easily politicised or associated with party politics. As the quote shows, one way of managing this dilemma is to reframe the issue so that it fits within another concept that is perceived to be less political, making it easier to implement the issue effectively. The cross-sector strategist also mentions the importance of being sensitive to which way the political winds are blowing and striking while the iron is hot, illustrated here by a youth strategist:

When you are in city hall, you pretty soon get a feeling about what is on the table and what is not. Like when 75 per cent [of politicians] are discussing public health. You quickly realise which perspectives to use as a frame [for your issues]. But of course, there are logical reasons why the youth perspective should be placed under public health; we are really working in relation to the same target group. In general, it is just the feeling about what is on the agenda, and the public health perspective has become very prominent in the municipality during the last year.

(Youth strategist 1)

As illustrated, an important strategy is to be sensitive towards what is going on and to move policies in that direction. Earlier studies show that framing is often used to gain influence. But this shows that it is also a coping strategy to manage depoliticised policy conflicts. If they do not use language to reframe an issue, they run the risk of not being able to produce an outcome at all or to ignite a latent conflict. This process of reframing also has a depoliticising effect since, instead of highlighting a potential conflict between or within a policy area, such as prioritising between public health and youth work, it might also mean that potential conflicts stay hidden.

Technical depoliticisation

In the politico-administrative system of local governments, politicians direct the work of the administration and are in charge of making priorities between policy issues. However, as we have seen, politicians can be reluctant to make such political priorities. One strategy among administrators that emerges from the interviews is to use statistics and other “factual” information as a tool to strengthen the argumentation on how to prioritise:

R: You choose to make priorities. It is very important, like now, for example, when we have chosen to prioritise the conditions in which children and young people are brought up. The group for the elderly and the advisory board for pensioners ask: ‘What about the elderly, are they not important?’ And of course they are. We are not suggesting that nothing will be done for the elderly, but you have to make priorities because there are not enough resources to devote to everything.

I: How do you argue the case for it?

R: Statistics. The experiences of the administration. And the socio-economic approach – the cost of not preventing social exclusion. It is the cost of a whole life. But then again, there is of course also a cost if you fall and break your hip.

(Public health strategist 2)

As the quote shows, administrators use statistics as a tool to strengthen their argument regarding which policies to push. A cross-sector strategist for sustainability elaborates on why they use this strategy:

Maybe it is wrong to say something like this, but I see my mission as bigger, to facilitate the voices that politicians are actually there to hear. I do not perceive myself as just the extended arm of politics. I see it as my role to show that this is what society is like; you must form an opinion on it for us to provide proper material. Maybe that could be interpreted as an administrative regime, but I do not see it that way.

(Sustainability strategist 3)

As administrators do not have the discretion to tell politicians what to do, one tactic employed by the administrators is to “show [politicians] what society is like”. Using statistics as a tool to inform politicians of what is the right policy to push is here described as a strategy to nudge politicians to work to promote a policy. A leading political representative for a municipality describes how such a process can take shape:

I: What types of issues can administrators push for?

R: I think it happens all the time. I have a sense that… Well, one of the issues where it is particularly clear, that we have worked on in a more concentrated fashion lately, has been youth policies. We have established a guidance centre where all community members between the ages of 16 and 24 can go to obtain guidance on various matters. (…) The idea came from the administrative level, where there had been a number of governmental investigations and found that other municipalities had tried this, and they thought that this could be something for our municipality as we have a high unemployment rate among young people. (…) And so… an idea was born in the administration, and the political level said “Yes, let’s do it”.

(Chair of the Executive Committee)

The respondent describes the fact that the bulk of the relationships with administrators are in the form of controlling or supervising the administrative operations. However, administrators sometimes present findings from governmental investigations or inputs regarding work being done in other municipalities that can encourage the political representatives to act.

It is important to get things on the agenda – the project that was undertaken last year would not have happened had I not reported the things I saw and presented the reoccurring statistical numbers. And I see it as my role to convey what things are like. I can also convey the fact that things are better or worse compared to other municipalities, and then deciding whether it is a priority or not is up to the politicians. My role is to convey the images in any way I can, with differing levels of persistence and energy.

(Safety strategist 1)

As the quote above shows, this strategy of using statistics to ‘make your case’ can bear fruit and help nudge decision-makers to prioritise the policy area in question. It is also a strategy that can be used in order to talk about the policy area in a more politically neutral tone, thus making it more appealing to politicians from all political parties. A cross-sector strategist for public health elaborates on this:

We have a centre-right majority here, and you are thus directly reminded about politics to some extent. This [policy field] is mainly associated with the left wing, a lot of social democracy. (…) No one wants to just go ahead and take it on, and I think that might be because it feels highly political. So my approach to it is not that I have a political affiliation and value in relation it, but rather that it is important from a public health perspective. We have scientific backing, but it gets complicated, loaded, a bit tricky. And I think that’s because it kind of touches on and awakens so many connections of a political character. So what we have tried to do then, kind of from the micro level, is to be very alert. For example, (…) instead of talking about equality, you can talk about how all children in municipality X should have the same opportunities for a good life. If I choose to speak about equality, I am given the cold shoulder from a large proportion of the politicians.

(Public health strategist 3)

To recapitulate, as administrators are the agents in the principal-agent relationship within the municipal organisation, they are disinclined to tell politicians what to do and what priorities to make. One strategy that emerges from the interviews is that administrators can use statistics and other factual information to strengthen their arguments in favour of their policy area. This is a way to present the policy area in a politically neutral light, thereby increasing its appeal to politicians from all political parties. It is consequently a way to softly nudge decision-makers in the direction that favours their policy area.

Getting attention of politicians

Delegation is not just a way to divide the workload in a politico-administrative relationship, it is also a way to place issues at one remove from politicians. Even though some administrators accept this delegation, not all of them follow this traditional division. Meaning that in addition to the two previous framing strategies for managing depoliticisation, we find indications of a previously unknown strategy—repoliticisation. Below, a cross-sector strategist for security reflects on how this separation affects the ability of cross-sector strategists to implement policies, with the conclusion that the separation is a hindrance:

I used to be placed in the emergency services department. In a department, not even physically in the Town Hall. Which made me rather isolated from politics. And I could not really understand why I had a hard time pushing for my policy issues, why I was not able to move forward and get approval in certain situations. I understand that now. Because to move forward, you need to have the politics with you to obtain a stronger emphasis in the matter. (…) The politicians should not be kept away as much as possible, which was my approach in the beginning. That it was easiest to keep things within the administrative level. But no! Try to involve them, that is what makes it easy. Because then you get some instruments to apply pressure and actually move forward.

(Security strategist 3)

The administrator describes the fact that her perspective on the politico-administrative relationship has changed. When they started working in the municipal organisation, they endeavoured to keep politicians at arms length. But in recent years, the modus operandi has been the opposite, with the administrator instead working to involve politicians as much as possible. By attaching politicians and the political level to the implementation of policy issues, administrators strive to (re)politicise issues and counteract delegation.

Below, a cross-sector strategist reflects on what consequences an unexpected politicisation of the policy perspective has for the situation. In this particular situation, the social-conservative party Sweden Democrats were against the work with gender equality and, due to the party’s controversial position in Swedish politics, the other parties mobilised around this policy field in order to safeguard it:

Everything about gender equality that has passed through the council has been empowered to have an impact thanks to him [a Sweden Democrat politician] being like that. Being ‘No’. (...). I was in the Sweden Democrats’ programme for cutting costs, so I was kind of like ‘OK, kick me out’. And then my boss said, ‘You are the only one who is safe in the entire organisation’. (...) Do you understand? Opposition is actuation, there are many forces that empower a perspective, and every now and then the Sweden Democrats are a factor.

(Gender equality strategist 1)

As the quote shows, the administrator who is the leading coordinator for gender equality in the municipal organisation describes a situation where gender equality has suddenly risen to the top of the political agenda. When politicians from different political parties politicise issues and debate aspects of an issue, a spotlight is shone on the policy area and the administrators working with it. The renewed attention from politicians has empowered the work within gender equality.

A recurrent theme in the interviews is that administrators describe the fact that there is a constant risk of their perspectives being neglected. The strategists then feel that it is their responsibility to ensure that the organisation integrates these issues into municipal operations, which means that they have developed counter tactics in order to stay on the agenda. A strategist for sustainability provides this description:

It is also about lobbying for the issues within the organisation, because although politicians say ‘now we will work with this’, it still requires as an administrator that you have to… not defend, but you have to lobby for your policy field. That is, you have to make the issues visible and you have to create a good relationship with the public, civil associations or other parties. You also have to build a good relationship with politicians so that you always have a good line of communication.

(Sustainability strategist 3)

As the quote shows, the administrator describes that as a part of a repoliticisation strategy, they strive to counteract the risk of other actors neglecting their policy field by lobbying for their policy field and to create a good relationship with politicians. This means that they advocate for their policy field with the intention of influencing decisions in a direction that is favourable for their policy perspective.

How do local government administrations manage depoliticisation?

In this section, we discuss how respondents perceive depoliticisation as a whole and how their work might be connected to it. We will then move on to present findings from the interviews and link them to strategies for managing depoliticisation found by previous scholars in the field.

It is often argued that depoliticisation shields politicians and their actions from critique and accountability. In findings from this study, we also learned that when political representatives agree on loosely formulated objectives and delegate responsibility for a policy area to the administration, it often means that the administrator in charge is given far-reaching discretion, but with no resources allocated to assist with the work. This might mean that depoliticisation can be a tool politicians use to not only avoid critique, but also to manage conflicts that occur between political parties at political level—out of sight, out of mind. Moreover, institutional depoliticisation regards a formal principal-agent relationship, with the principal (the politician) setting directives and broad boundaries for policies, and the agent (the appointed administrator) in charge of the everyday operations. Delegation, or arena-shifting, is a way to divide the workload in a politico-administrative relationship. But it is also a way to situate issues at one remove from politicians—thus contributing to their depoliticisation. However, the administrators describe the fact that although they are aware of this division of labour, they do not always accept it.

One strategy that the administrators use is that while they feel there might be politicisable aspects to their policy field, they choose not to challenge the depoliticisation. Instead, they endeavour to reframe their work in a way that is perceived to be less political. This means that they are creative in terms of connecting solutions and problems in a convincing and innovative manner, which can be interpreted as making use of so-called “windows of opportunity” (Kingdon 1995). They use the legitimation their profession provides, and the discretion delegated to them to reframe a problem. Reframing to gain influence is well established in earlier studies, but our findings indicate that it is also a coping strategy used by administrators to manage depoliticised policy conflicts with the aim of avoiding igniting latent conflicts.

Technical depoliticisation means that issues are framed in such a way as to have a single rational or technically correct solution. As administrators do not have the discretion to tell politicians what to do, this strategy is employed by administrators to “show [politicians] what society is like”. This is done by using statistics and ‘factual’ information, such as governmental inquiries, that are regarded as objective or neutral. While statistics and facts can serve different purposes, they are here described as tools to build up an argumentation regarding what is a “correct” or rational course of action. The aim of this strategy is to enlighten political decision-makers of the importance of their policy areas and is intended to nudge politicians to form political opinions that favour their policies and to push for their policy fields. This can be interpreted as a soft approach that resembles knowledge management.

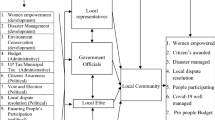

Findings revealed a third and less known framing strategy to manage this situation—to actively counter depoliticisation and to work to involve political representatives as much as possible. By connecting politicians and the political level to their work on policy issues, administrators attempt to repoliticise issues and to counteract the delegation and arena-shifting. The underlying reasoning for this strategy is that administrators do not always accept the delegation from the political arena to the administrative arena, and instead venture to actively involve politicians in the details of its operation. When politicians and other decision-makers insist that an issue lies outside political control it hampers the administration’s ability to work with the issue. As a part of this strategy, administrators also conduct lobbying, meaning that they advocate for their policy field within the municipal organisation with the aim of shedding light on its importance and political power. The intention is to influence political decision-makers and decisions in a direction that is favourable for their policy perspective (Table 1).

Discussion

From earlier scholars we learn that there are at least two framing strategies, (re)framing and technical depoliticisation, which administrators can employ to gain influence or to cope with ambiguous situations. We have argued that a context filled with unresolved policy conflicts can be understood as ambiguous, giving rise to mixed signals and cross pressures, and as such would prompt the use of these strategies. While our results showed that these strategies are employed, this study also reveals that public administrators employ a third and less known frame: repoliticisation. Before we can discuss the study’s implications, we will first discuss why unresolved policy conflicts exist.

Political representatives can, at times, attempt to avoid conflicts by agreeing to loosely formulated goals for the administration. Resulting in situations where unresolved conflicts from the political arena can be pushed, through so-called arena-shifting, into the administrative arena. This may lead to situations where conflicts between political parties are glossed over, hidden, or concealed. When different, and even conflicting, objectives are added on top of one another and delegated away from politicians, their inherent conflicts or political power are left formally unacknowledged. When administrators are given such loosely formulated goals and endeavour to implement them, they first need to find a more specific definition of their objective. As seen in Sect. 4.1, they are put in the ambiguous situation of being given wide-ranging discretion with regards to formulating what is to be done and in what time frame, but at the same time are often left with little to no resources to fund their work, making implementation of any real policy reforms problematic. One possible interpretation of why political leaders repeatedly put administrators in such situations is that it enables politicians to avoid blame for not having initiated administrative operations within a policy area, while at the same time also preventing them from being held accountable for implementing policies that can be perceived to be politically precarious or even risky. This means that perhaps the simple action of putting an administrator in charge of a policy area is a tool for conflict management used by political leaders, and that whether or not these administrators actually are effective in implementing their objectives is of secondary importance.

This study reveals that administrators use different strategies to manage depoliticisation. While some administrators may agree with, or at least accept, depoliticisation and at times contribute to it by hiding conflicts—others work to counteract the development and endeavour to repoliticise it and attract attention to their political power.

It could be argued that depoliticisation may lead to faster implementation where decision-makers can implement policies without drawing public attention to them. But it is only through democratic processes that we can find out which solutions are both appropriate and efficient. Depoliticisation gives rise to a democratic dilemma; political representatives are responsible for all matters undertaken by their administration, but when issues are depoliticised, the ability of citizens to hold their representatives accountable is disrupted. Moreover, it is not always possible to base solutions to political conflicts on reason or ‘common sense’, or to reduce them to technical issues best handled by professionals. Solutions to or outcomes of political decisions can, however, be the result of discussions or compromises where each political actor is made aware of the consequences of each choice (Gutmann and Thompson 2009; White and Ypi 2011) and where such disagreements are displayed openly, thereby fostering transparency and accountability. As conflicts also have productive qualities, such as preventing tunnel vision and spurring innovation (Cuppen 2011; Coppens 2014), attempting to depoliticise conflicts might also mean losing out on reaping their benefits. This means that the new strategy of repoliticisation, where administrators lobby to shed light on the political power of their policy field, may be of importance not only for the individual administrator’s ability to produce an outcome—but for the democratic systems ability to thrive in the long run.

Notes

The book The Spirit Level – Why more equal societies almost always do better by Kate Wilkinson and Richard Pickett, was published in Sweden in 2010 and generated strong reactions in the media.

References

Bengtsson, M. 2012. Anteciperande förvaltning. Ineko: Göteborg.

Blinder, A.S. 1997. Is government too political. Foreign Affairs 76: 115–126.

Blom-Hansen, J., M. Bækgaard, and S. Serritzlew. 2021. How bureaucrats may shape political decisions: The role of policy information. Public Administration 99 (4): 658–678.

Burnham, P. 2001. New labour and the politics of depoliticisation. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 3 (2): 127–149.

Bäck, H. 2003. Party politics and the common good in Swedish Local Government. Scandinavian Political Studies 26: 93–123.

Cairney, P. 2018. Three habits of successful policy entrepreneurs. Policy & Politics 46 (2): 199–215.

Carstensen, M.B., and V.A. Schmidt. 2016. Power through, over and in ideas: Conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy 23 (3): 318–337.

Chech, E.A. 2013. The (mis)framing of social justice: why ideologies of depoliticization of meritocracy hinder engineers’ ability to think about social injustices. In Engineering education for social justice, vol. 10, ed. J. Lucena. Dordrecht: Springer.

Chong, D., and J.N. Druckman. 2007. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 103–126.

Coppens, T. 2014. How to turn a planning conflict into a planning success? Conditions for constructive conflict management in the case of Ruggeveld-Boterlaar-Silsburg in Antwerp, Belgium. Planning Practice and Research 29: 96–111.

Christensen, T., O.M. Lægreid, and P. Lægreid. 2019. Administrative coordination capacity; does the wickedness of policy areas matter? Policy and Society 38 (2): 237–254.

Cox, R.H., and D. Béland. 2013. Valence, policy ideas, and the rise of sustainability. Governance 26 (2): 307–328.

Cuppen, E. 2011. Diversity and constructive conflict in stakeholder dialogue: Considerations for design and methods. Policy Sciences 45: 23–46.

Etherington, D., and M. Jones. 2018. Re-stating the post-political: Depoliticization, social inequalities, and city-region growth. Economy and Space 50 (1): 51–72.

Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2012. The Depoliticization of inequality and redistribution: Explaining the decline of class voting. The Journal of Politics 74 (5): 963–976.

Flinders, M., and J. Buller. 2006. Depoliticisation: Principles, tactics and tools. British Politics 1 (3): 293–318.

Gutmann, A., and D. Thompson. 2009. Democracy and disagreement. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Hajer, M., and H. Wagenaar, eds. 2003. Deliberative policy analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hartley, J., J. Alford, O. Hughes, and S. Yates. 2015. Public value and political astuteness in work of public managers: The art of the possible. Public Administration 93 (1): 195–211.

Hay, C. 2007. Why we hate politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hood, C. 2002. The risk game and the blame game. Government and Opposition 37 (1): 15–37.

Hysing, E. 2014. How public officials gain policy influence - lessons from local government in Sweden. International Journal of Public Administration 37 (2): 127–139.

Kingdon, J.W. 2003[1984]. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Knaggård, Å. 2016. Framing the problem: Knowledge brokers in the multiple streams framework. In Descision-making under ambiguity and time constraints, ed. Zohlnhöfer and Rüb, 109–123. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Lan, Z. 1997. A conflict resolution approach to public administration. Public Administration Review 57 (1): 27–35.

Lipsky, M. 1980. Street level bureaucracy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Mintrom, M., and J. Luetjens. 2017. Policy entrepreneurs and problem framing: The case of climate change. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (8): 1362–1377.

Mintrom, M., and P. Norman. 2009. Policy entrepreneurship and policy change. Policy Studies Journal 37 (4): 649–667.

Maor, M. 1999. The paradox of managerialism. Public Administration Review 59 (1): 5–18.

Molenveld, A., K. Verhoest, and J. Wynen. 2020. Why public organizations contribute to crosscutting policy programs: The role of structure, culture, and ministerial control. Policy Sciences 1–3.

Moore, M.H. 2014. Public value accounting: Establishing the philosophical basis. Public Administration Review 74 (4): 465–477.

Mouffe, C. 2005. On the political. London: Routledge.

Nielsen, V.L. 2006. Are street-level bureaucrats compelled or enticed to cope? Public Administration 84 (4): 861–889.

Niemann, C. 2013. Villkorat förtroende. Department of Political Science, Stockholm University.

Olsson, J. 2009. The power of the inside activist: Understanding policy change by empowering the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF). Planning Theory and Practice 10 (2): 167–187.

Rhodes, R.A.W., and J. Wanna. 2007. The limits to public value, or rescuing responsible government from the platonic guardians. The Australian Journal of Public Administration 66 (4): 406–421.

Rosenbloom, D. 1983. Public administrative theory and the separation of powers. Public Administration Review 43 (3): 219–227.

Schmidt, S.M., and T.A. Kochan. 1972. Conflict: Towards conceptual clarity. Administrative Science Quarterly 13: 359–370.

Scott, R.W. 1981. Organizations: Rational, natural, and open systems. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Seabrooke, L., and D. Wigan. 2016. Powering ideas through expertise: Professionals in global tax battles. Journal of European Public Policy 23 (3): 357–374.

Sellers, J., A. Lidström, and Y. Bae. 2020. Multilevel democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Simon, H. 1946. The proverbs of administration. Public Administration Review 6 (1): 53–67.

Skoog, L. 2019. Political conflicts - Dissent and antagonism among political parties in local government. Göteborg: Brandfactory.

Skoog, L. 2021. Where did the party conflicts go? How horizontal specialization in political systems affects party conflicts. Politics & Policy 49 (2): 390–413.

Skoog, L., and D. Karlsson. 2022. Perception of polarisation among political representatives. Political Research Exchange 4 (1): 2124923.

Strøm, K., W.C. Müller, and T. Bergman. 2003. Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Svensson, P. 2018. Cross-sector strategists. Dedicated bureaucrats in local government administration. Göteborg: Brandfactory.

Svensson, P. 2020. Komplex helhetsstyrning: Att integrera allt med allt. Socialmedicinsk Tidskrift 97 (4): 683–694.

Svara, J. 2006. Complexity in political-administrative relations and the limits of the dichotomy concept. Administrative Theory and Praxis 28 (1): 121–139.

van Dorp, E.-J., and ’t Hart, P. 2019. Navigating the dichotomy: The top public servant’s craft. Public Administration 97 (4): 877–891.

White, J., and L. Ypi. 2011. On partisan political justification. American Political Science Review 105 (2): 381–396.

Winter, S., and V.L. Nielsen. 2008. Implementering af politik. Aarhus: Academica.

Wolf, E.E.A., and W. Van Dooren. 2018. Conflict reconsidered: The boomerang effect of depoliticization in the policy process. Public Administration 96 (2): 286–301.

Wood, M., and M. Flinders. 2014. Rethinking depoliticisation: Beyond the governmental. Policy & Politics 42 (2): 151–170.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council under Grant [2017-02169].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skoog, L., Svensson, P. Hidden policy conflicts? Administrative strategies to manage depoliticisation. Acta Polit 58, 819–836 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00266-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00266-3