Abstract

Scholars trying to understand attitudes toward the European Union (EU) are increasingly interested in citizens’ basic predispositions, such as the “Big Five” personality traits. However, previous research on this particular relationship has failed to provide sound hypotheses and lacks consistent evidence. We propose that looking at specific facets of the Big Five offers a deeper understanding of the associations between personality predispositions, their measures, and EU attitudes. For this purpose, the 60-item Big Five Inventory-2, which explicitly measures Big Five domains and facets, was administered in a German population sample. We applied a variant of structural equation modeling and found that personality predispositions promoting communal and solidary behavior, cognitive elaboration, and a lower tendency to experience negative emotions predicted support for further European integration. Greater support of European integration might thus reflect, in part, basic psychological predispositions that facilitate adapting to the political, social, and cultural complexity posed by Europeanization. The study thus contributes to our understanding of deep-rooted patterns in thoughts and feelings that can shape citizens’ EU attitudes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Policy-makers and researchers alike seek to understand why citizens differ so profoundly in their attitudes toward the European Union (EU)—not just since the recent economic crisis and the so-called refugee crisis. Trying to understand support for the EU is vital, because the position on European integration might become another super issue besides the ideological left–right axis, thus shaping new political conflict lines (Otjes and Katsanidou 2017). However, while numerous socio-economic and attitudinal antecedents have been identified to link with pro-/anti-EU attitudes (see, e.g., Hobolt and de Vries 2016), very little attention has been given to fundamental predispositions, namely citizens’ deep-rooted personality differences.

The present study aims to contribute to a very recent strand of research that addresses antecedents of EU attitudes from a psychological or individual difference perspective, thus focusing on citizens’ personality predispositions (see, e.g., Curtis and Nielsen 2018). Personality traits are usually described as relatively stable individual differences in behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. These differences can also affect individuals’ political preferences. A common argument, which is called the cognitive-motivational approach, is that political preferences (or belief systems) resonate with citizens’ deep-rooted social–psychological needs and interests, i.e., personality (Jost 2017).

Personality trait theories have mostly built on the “Big Five” framework, which describes the traits Open-Mindedness (or Openness to Experience), Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Negative Emotionality (or Neuroticism), and Extraversion as global personality “domains” (see Soto and John 2017; labels in brackets by Costa and McCrae 1995). Meanwhile, a considerable body of literature has studied how personality traits predict left–right or liberal–conservative orientations (see Gerber et al. 2011; Jost 2017), but only recently has scholarly work looked at these factors with regard to EU attitudes (e.g., Bakker and de Vreese 2015; Curtis and Nielsen 2018; Curtis 2016; Nielsen 2016, 2018; Schoen 2007).

There are good reasons to believe that citizens’ level of “default support” for the European project resonates with their personality. However, we argue that previous research has thus far failed to (1.) provide sound theoretical expectations, (2.) present consistent empirical evidence, and (3.) overcome certain methodological limitations related to measuring and analyzing personality traits.

In this study, we aim to elaborate on a set of hypotheses and we present novel data as well as a framework for analyzing associations with specific personality traits, so-called facets. In particular, we distinguish between specific personality facets among the global Big Five domains (see Costa and McCrae 1995) when looking at associations with EU attitudes. For this purpose, we investigate European integration attitudes using unique data from a German population sample where the 60-item Big Five Inventory-2 (BFI-2; Soto and John 2017; see Danner et al. 2019 for the German version) was administered. The article closes by discussing the findings’ contribution to our understanding of how deep-rooted patterns in thoughts and feelings can shape the way citizens approach EU politics.

Issue 1: previous expectations on the Big Five and EU attitudes

Very few studies have so far investigated associations between the Big Five traits and EU-related attitudes (see Table 1). Regarding the dependent variable, apart from Curtis (2016) who specifically looks at European identity or Bakker and de Vreese (2015) who also consider trust and affect, these studies generally measured attitudes on “strengthening” the EU (Boomgaarden et al. 2011), i.e., approval of deepening/widening of the EU, policy transfer, and extended decision-making competencies. In what follows, we thus particularly focus on this dimension (“strengthening”), considering that different dimensions of EU attitudes are likely to have different predictors (see also Boomgaarden et al. 2011).

As can be seen, there is an apparent lack of consensus regarding the theoretical underpinnings of associations with the dependent variable (see Table 1, column “Hypotheses”). Yet, one might object that the studies mentioned are quite heterogeneous in terms of the attitudinal concepts, i.e., EU support, being measured (the D.V.), they differ in the measures used to assess the Big Five (the I.V.), the countries studied (context), and the control variables employed (confounders). Still, the measures (standardized scales/items) and cases (apart from Poland, older EU member states) bear some similarity. Having said that, when studying basic traits, such as the Big Five, one could argue that we can expect universal patterns that transcend the specific operationalization used or even the context.

Issue 2: the evidence so far

As can be seen in Table 1, it is also safe to say that there is a lack of consistency in empirical results obtained so far (see also Curtis and Nielsen 2018). In sum, studies have often faced “unexpected associations between personality traits and EU attitudes” (Bakker and de Vreese 2015, p.37) or, in other words, erratic associations. Apart from Open-Mindedness (or Openness), there is basically no agreement in the associations between “strengthening” the EU and Big Five traits (see Table 1, column “Effects”). In summarizing, it seems that the literature on this topic still faces lots of preliminary evidence.

A different argument, however, would be that relationships between dispositional variables and political preferences are necessarily contingent on the “context” or the political discourse individuals are exposed to (see Federico and Malka 2018). In particular, this might have to do with the prevailing perception of a country’s EU membership or the EU as a political actor as well as how citizens’ EU attitudes are aligned with other ideological attitude dimensions.

Issue 3: measuring and analyzing personality traits

A number of methodological concerns can also be raised in relation to research on personality and politics. This problem has been stressed by other authors in the personality politics literature, such as Gerber et al. (2011, p. 280), who note that “[…] measurement issues may also explain some of the inconsistencies in findings […].” As will be explained below, the main reasons are three interrelated issues.

First, extensive personality inventories used in psychological assessment, such as the famous NEO PI-R (Costa and McCrae 1995), cannot be used for practical reasons.Footnote 1 As can be seen in Table 1 (column “Measure”), previous works have therefore used diverse measures of the Big Five with shorter scales of 10 up to 60 items. Using (extremely) short measures, however, naturally comes at the price of lower reliability and validity and could entail a misrepresentation of empirical relationships (Bakker and Lelkes 2018; Credé et al. 2012; Gerber et al. 2011).

Second, because of using shorter scales, it follows that the lower-level structure of the Big Five domains (i.e., the facet-level traits; see Table 2) has been neglected thus far. Inconsistent results might also be explained by the fact that various short-form Big Five batteries naturally differ in their weight they assign to personality facets, which are then covered by the measure (see also Gerber et al. 2011, p. 280; Bakker and Lelkes 2018, p. 1312). Donnellan et al. (2006) report that the two most frequently used scales, Mini-IPIP and TIPI, emphasize certain facets of the Big Five more so than others. However, the two measures show a similar pattern of content coverage, i.e., they exhibit similar associations with Big Five facets. Overall, this would allow for comparability of broad domain-level associations with the Big Five between Mini-IPIP and TIPI, given that (un)reliability has been taken into account.

Moreover, there might be theoretically more sound associations between specific facets and EU attitudes (i.e., fidelity). In particular, because of higher fidelity, facet-level analyses should yield higher predictive power for attitudes or behavioral outcomes (Paunonen and Ashton 2001). One reason is that facets are less abstract (e.g., the trait interpersonal Trust, rather than Agreeableness) and, hence, they operate at a similar level of abstraction as policy attitudes. Additionally, if associations with subfacets exhibit different magnitude, no association or even opposing signs, the overall domain effect is less clear. Gerber et al. (2011, p. 282) therefore recommended that “facet-level personality measures may help to address this measurement issue.”

A third problem is imperfect measurement reliability of manifest scale scores (i.e., the sum score of items), which generally decreases with the number of items used (e.g., Bakker and Lelkes 2018). Short-form measures of the Big Five are therefore particularly prone to this problem. As a consequence, observed/manifest variable associations will usually be attenuated by unreliability and the results for a standard regression model, for instance, can be very different with and without correction for measurement errors (e.g., Saris and Revilla 2016). We therefore argue that the method of structural equation modeling (SEM) is generally better suited than manifest variable analysis, as also discussed below. Note, however, that none of the studies reported in Table 1 applied SEM. Therefore, we also compared our substantive results to other classical modeling strategies in the results section.

In sum, the present study aims to substantiate the extant evidence and tries to overcome the limitations mentioned.

Hypotheses

Below, we now provide a brief sketch of the Big Five personality trait domains and facets (see Table 2) in order to clarify and put forward explicit hypotheses, stressing potential facet associations with attitudes on strengthening the EU or support for European integration.

Open-Mindedness describes a “mental tendency” for a “wide versus narrow range of perceptual, cognitive, and affective experiences” (Soto and John 2017, p. 120). It might relate to tolerance of diversity (Nielsen 2016), “broadness of one’s own cultural interest,” as well as support for “international involvement” (Schoen 2007, p. 412), and it should resonate with developing a European identity (Curtis 2016). Accordingly, we hypothesize that Open-Mindedness should generally have a unique positive association with strengthening of the EU. As regards facet-level associations of Open-Mindedness, previous research suggested that facets of openness to new ideas, others’ values, or curiosity might matter more for one’s political views than experiential aspects, such as aesthetic appreciation or creativity (see Sibley and Duckitt 2010). We hence expect that the former aspects/facets (BFI-2 Intellectual Curiosity and Creative Imagination) are more important for explaining EU attitudes, because higher Open-Mindedness allows individuals to more easily adapt to the political, social, and cultural complexity posed by Europeanization.

Agreeableness generally describes the “quality” of interpersonal behavior and interaction. We hypothesize that Agreeableness resonates with strengthening of the EU, because it facilitates trust in strangers beyond the in-group, it is a basis for institutional trust (Easton 1975), and it facilitates feelings of sympathy and solidarity with people from other EU member states.Footnote 2 Another aspect of Agreeableness relates to the desire to relate and cooperate with others, also labeled Communion (Bakan 1966). As regards facet associations in the BFI-2, we therefore expect that Trust in the benevolent intent of others, concerns about benevolence of others or Compassion might matter more than politeness or Respectfulness aspects (see Hirsh et al. 2010). Interestingly, however, Bakker and de Vreese (2015) found even a negative or no associations between domain-level Agreeableness and EU attitude dimensions.

Conscientiousness can have proactive sides, such as need for achievement and commitment, and inhibitive sides. Previous works (see Table 1) basically stress the latter aspect, arguing that conscientious people are traditional, reluctant to change, favor the status quo, and like order (inhibitive, BFI-2 Organization). Yet, this also bears some resemblance to authoritarian attitudes. Following this notion of Conscientiousness, one should expect a negative association with a desire for strengthening the EU. Schoen (2007, p. 413) further speculates that individuals high in Conscientiousness “may regard international involvement as an appropriate means to pursue a goal,” which would relate to aspects of proactive behavior (BFI-2 Productiveness or Dutifulness) or overall Agency (see Bakan 1966). Using this very argument, Nielsen (2016) postulated a positive correlation with pro-EU attitudes, whereas Schoen (2007) finally postulated a negative association. We follow the notion that facets of proactive behavior (or Agency) might even positively link with pro-EU attitudes.

Negative Emotionality describes a tendency toward negative emotional experiences. We hypothesize that Negative Emotionality and strengthening of the EU will be negatively related, because of the motivation to avoid uncertainty or social complexity entailed by Europeanization (Nielsen 2016) as well as to avoid social isolation in a supra-national community (Curtis 2016). This notion disagrees with Bakker and de Vreese (2015), who expect a positive association between Negative Emotionality with deepening/widening of the EU, because the EU could accommodate the experienced fear caused by globalization (Europeanization). We postulate that tendencies described by BFI-2 Anxiety and Depression are likely to have a negative impact, because political, social, and cultural complexity may entail greater distress.

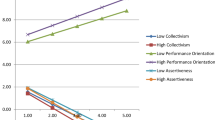

Extraversion is a “social tendency” that describes openness to and the preferred quantity of social experiences. However, it is often mistaken for behavioral traits attributable to high Open-Mindedness and low Conscientiousness, arguing that more extraverted people seek new information, they challenge established beliefs, and are more adaptable (see, e.g., Nielsen 2016). Given this ambiguity and the typical non-correlation with political orientations (Gerber et al. 2011), we have no strong expectations about specific Extraversion facets and EU support. However, from what has been said so far, individual pro-sociality (Sociability), approach behavior (Energy Level), and goal attainment (Assertiveness) could, overall, facilitate a preference for more international involvement and strengthening of the EU.

Data and analysis

Case

We tested our predictions in the German context. Traditionally, the German electorate shows overwhelming support for EU membership, despite clear criticism by supporters of the AfD and, to a minor extent, also by the Left. This majority in favor of the EU has even increased since the Brexit referendum in June 2016. For example, around the time of the interviews (in May 2017), according to Eurobarometer data (EB 87), 23% and 52% of Germans reported that they feel “very” and “fairly” attached to the EU (vs. 17% and 46%, respectively, on EU average). Trust in the EU increased from a record low in May 2016 (28%) to 37% in Fall 2016 and 44% in May 2017.

Regarding the association between EU attitudes and ideological attitudes, it can be expected that EU attitudes in Germany strongly blend into the sociocultural issues dimension, such as positions on immigration or authoritarian attitudes, rather than economic issue attitudes (see, e.g., Otjes and Katsanidou 2017). Thus, it is more likely that personality predictors of support (strengthening) of the EU also resemble those of the former dimension, rather than the latter dimension.

Sample and measures

In order to test our hypotheses, we make use of a unique study conducted in Germany. Respondents were interviewed online (CAWI) by a German commercial online access panel (Respondi AG) in December 2016. The sample was a quota sample (based on age, gender, and education) according to the German census 2011. As a quality indicator, participants who either failed an attention check question or answered items in less than 3 s or more than 30 s on average were excluded ex-ante (n = 114 in total), which resulted in an initial sample size of n = 1224.

Respondents were asked whether European unification has gone too far (0) or should go further (10) (M = 4.7, SD = 3.1), a measure frequently used in social and political surveys that fits with the “strengthening” dimension of EU attitudes (Boomgaarden et al. 2011). We use it as the dependent variable in our analysis.Footnote 3

Personality was measured with the 60-item Big Five Inventory-2 (BFI-2). The BFI-2 aims to measure the five major personality domains and a hierarchical structure with three facets within each domain (see Table 2 above; Soto and John 2017). Each facet was measured with four items formulated as short, mostly behavioral self-descriptions (e.g., “I am compassionate, have a soft heart”; see Soto and John 2017 or Danner et al. 2019 for the full list). To mitigate acquiescence bias two items per facet were positively poled and two negatively poled, respectively. Items could be answered on a fully labeled 5-point rating scale (1 = disagree completely to 5 = agree completely). This represents one of the most detailed measurements included in recent population surveys, thus allowing a fully fledged investigation of personality facets and EU attitudes.

The following control variables were included in the analyses, because these might correlate with EU attitudes and personality self-ratings: age in years; gender (male = 1); formal education (“lower secondary education,” “intermediate secondary education,” and “upper secondary or higher education”); personal net income using the means of income categories (M = € 1593, SD = € 1092); and individual religiosity (0 = not at all to 8 = absolutely; M = 2.0, SD = 2.5). In a second modeling step, we further control for respondents’ self-placement on a traditional left–right scale (0 = left to 10 = right) to ensure that personality effects are not the result of mere mediation via differences in ideological core attitudes (see also Curtis and Nielsen 2018).

Analysis: structural equation modeling

Two problems stand out when trying to analyze specific personality traits (facets). Manifest scale scores would include the commonality shared with the global domain as well as facet-specific variance (e.g., overall Open-Mindedness and Aesthetic Sensitivity; see McCrae 2015). Hence, these cannot be accurately distinguished. Second, manifest scale scores additionally exhibit imperfect reliability (measurement error) which, as already mentioned, generally biases correlations with a criterion (i.e., outcome) measure (Saris and Revilla 2016).

In this study, a so-called bifactor structural equation model (SEM) was employed for modeling and analyzing the hierarchical structure of personality domains and facets. Bifactor models are very common in intelligence assessment, for instance, where general intelligence is distinguished from its facets, such as verbal, spatial, mathematical, and analytic abilities. Facets (i.e., the factors loading on facet-specific items) thus represent the incremental information beyond the global domain (i.e., the factors loading on all items of a domain). These different factors—domains and facets—can be distinguished using latent variables in SEM, which allows analyzing both at the same time (e.g., Chen et al. 2012). The bifactor SEM used here specifies that global domain factors were correlated, all latent facet variables were uncorrelated, and an orthogonal method factor was included to partial out acquiescence bias.Footnote 4 Note that, because facet and domain variables are uncorrelated in bifactor models, we can assess their unique contribution (incremental predictive validity) in a regression model (Chen et al. 2012).

Furthermore, when using SEM the structural relationships between variables are corrected (disattenuated) for measurement errors. For the final SEM specification, attitudes toward European integration were regressed on the facet and domain variables, the socio-demographic controls and, in a second step, on left–right self-placement (14% of the initial sample had missing values on this variable).Footnote 5 We hence restrict our sample size to respondents with non-missing values in these variables (n = 899).

Results

We, first, investigated the overall goodness-of-fit criteria of a bifactor measurement model to fit the theoretical structure of the BFI-2. This model showed acceptable fit, but suggested that five of the hypothesized facets could not be sufficiently identified.Footnote 6 We also ran a 5-factor EFA model to see whether item cross-loadings could produce model misfit (See Online Supplemental Materials). After this first step, we proceed with a bifactor model excluding one item (i42r) due to high cross-loadings and exclude the five facets that were insufficiently identified.

The model fit indices for the bifactor model used were as follows: χ2(1602) = 5273.5; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.833; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.047 [0.045; 0.048]; SRMR = 0.073. Note, however, that, judging based on commonly used fit measures for SEM (e.g., Hu and Bentler 1999), the model fitted the data rather adequately. The more sensitive RMSEA (< 0.06) and SRMR (< 0.08) indices suggested that the model was accurately specified, only the CFI is just below standard requirements of “sufficient” model fit (< 0.90). However, it is likely that a low CFI is also due to weak observed variable correlations and slightly non-normal data. We are nevertheless confident that the bifactor models were overall correctly specified and proceeded by accepting and interpreting its results.

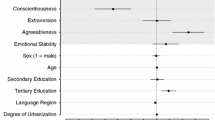

Table 3 presents the results for the bifactor SEM which regressed support for European integration on the latent personality domains and facets, including socio-demographic covariates (Model 1) and, additionally, left–right self-placement (Model 2). The results in Table 3 suggest unique and statistically significant contributions of specific personality facets over and above the global Big Five domains. As can be seen, Aesthetic Sensitivity was the facet of Open-Mindedness that had a unique and significant impact on support for European integration. In turn, this suggests that domain-level Open-Mindedness had little explanatory power beyond this specific facet. Furthermore, two of the Agreeableness facets, Compassion and Trust, were each positively and significantly associated with supporting European integration. In other words, both facets exhibit unique and incremental explanatory power. Contrary to expectations, Conscientiousness played virtually no role in predicting people’s EU attitudes. In turn, the overall domain trait Negative Emotionality was negatively and significantly related to support for European integration, whereas narrow facets showed no additional contribution over and above the general domain. Finally, neither the Extraversion domain nor its facet variables were significantly related with support for European integration. Finally, in line with previous research, a strong impact of higher formal education on positive EU attitudes was corroborated.

When including the left–right scale (Model 2), the aforementioned effects decreased somewhat, i.e., they were picked up (mediated) by ideological orientations to some extent, but remained statistically significant. In particular, the results clearly showed that respondents who consider themselves as ideologically right-wing were generally more critical of further European integration.

Supplemental analysis: SEM vs. alternative modeling strategies

We also compared the substantive results to other commonly applied modeling strategies (see the Online Supplemental Materials): standard regression analysis with manifest sum scores and regression on second-order factors in SEM (see Chen et al. 2012).Footnote 7 In general, regression analyses on either Big Five domain scores or second-order latent factors using SEM were very similar, because the reliability of the Big Five domain variables was relatively high (≥ 0.79). Also, all models agree that higher Open-Mindedness and higher Agreeableness favor EU support.

According to the alternative models’ results, however, Extraversion was negatively associated with EU support. When running a regression model with manifest facet scores instead, only Aesthetic Sensitivity turned out statistically significant, whereas none of the Agreeableness facets seemed relevant. In summarizing, the domain-level associations found seem to underestimate and neglect the influence of important facet-level associations (hence, potential Type I error), whereas observed/manifest variable analyses generally suffer from varying bias due to unreliability (attenuation) and might neglect incremental predictive power of a personality facet (see Westfall and Yarkoni 2016).

What is more, employing a facet-level analysis and the SEM technique yielded relatively high predictive power for the European integration attitudes (see R2 values in Table 4). More precisely, in comparison with previous studies, this modeling strategy substantially exceeded the explained variance on top of other explanatory variables (ΔR2; see Tables 1 and 4, respectively). The incremental explanatory power was also higher in comparison with the other modeling strategies, namely manifest sum scores of domains or facets only and modeling second-order factors in SEM (see Table 4).

Discussion

Summary and implications

This study set out to investigate personality traits or deep-rooted patterns in thoughts and feelings that shape citizens’ attitudes toward EU politics. For this purpose, we analyzed a core measure of public opinion: (dis)approval of further European integration. This single-item measure is most commonly used and conveys a general notion of support for the EU, but of course has known limitations. As expected, we found associations between EU attitudes and facets of higher Open-Mindedness, facets of higher Agreeableness, and lower Negative Emotionality, though not with Conscientiousness or Extraversion.

The fact that the results resemble those of Big Five facet associations with sociocultural policy attitudes (e.g., immigration; see Aichholzer et al. 2018) provides some indication that, at least in Germany, EU attitudes are somewhat aligned with this ideological axis. Our findings by and large also agree with previous studies conducted in Germany (Schoen 2007; Curtis and Nielsen 2018 DE sample; though see Extraversion).

In the introduction, we specifically set out to tackle a number of issues identified in previous works: elaborate on sound theoretical expectations, add to the existing but sparse evidence, and try to overcome methodological limitations by using Big Five facet-level analysis and bifactor SEM. We postulated that specific personality traits could better explain EU attitudes in terms of the substantive meaning we can attach to these associations, on the one hand, and with regard to explanatory power, on the other hand. Eventually, a more detailed measurement of Big Five facet-level traits in the BFI-2 and employing SEM allowed us to substantiate previous evidence and to overcome previous limitations. In particular, we did so by also comparing our results to more classical modeling strategies.

The proposed facet-level analysis provided a nuanced picture and revealed that more specific associations with citizens’ personality predispositions exist. Individual differences in Aesthetic Sensitivity (similar to Openness to Aesthetics), which originally measures sensitivity to and appreciation for art, mattered most for explaining support for strengthening the EU. This was contrary to our facet-level expectations. One explanation could be that it is a more “typical” facet of the Openness trait. Yet another interpretation is that Aesthetic Sensitivity represents aspects of cognitive elaboration and comfort with complexity (Onraet et al. 2011, p. 195). This facet might actually link with traits such as the Need for Cognitive Closure (negative association) or the Need for Cognition, subsumed as “cognitive style.” It could thus reflect an important default “epistemic” predisposition related to processing the complex political information entailed by Europeanization. These potential relationships thus deserve to be studied further.

The significant and unique effects for Compassion and Trust have to be seen in the light of Agreeableness being a domain that describes social and communal behavior. Dispositional Trust serves as the basis for trust vis-à-vis strangers (i.e., social trust) and could hence foster trust in other EU nationalities. On the other hand, Trust could provide a basis for institutional trust, a prerequisite when handing over political sovereignty to EU institutions. The Compassion facet (similar to Altruism) of Agreeableness, in turn, describes a tendency to helpful and unselfish behavior and might resonate with concerns over social equality and solidarity with other people from other EU countries. This is particularly important in the light of a potential “solidarity crisis” in recent years.

That people high in Negative Emotionality generally seemed to disapprove of further deepening or widening of the EU can also be interpreted from a cognitive-motivational perspective, which postulates that individuals’ political preferences are driven by epistemic and existential needs to deal with uncertainty and minimize perceptions of threat (Jost 2017). Increasing sociocultural variety, political uncertainty, and perceived lack of control entailed by Europeanization might impose a threat to individuals who already exhibit anxious, worrying, and emotionally unstable tendencies. Yet, the role of emotions more generally and emotions toward the EU also deserve to be studied further.

Conclusions

It is fair to say that the future of the EU, its legitimacy, and European integration depend on citizens’ approval. On a more general level, these and other results tap into citizens’ differential threshold for a “default support” for the European project. In sum, rejection of further European integration seems to reflect, in part, basic psychological predispositions that facilitate adapting to the political, social, and cultural complexity posed by Europeanization. Hence, this study highlights the importance of looking at more deep-rooted predispositions that potentially drive other important predictors of pro-/anti-EU attitudes, especially so-called identity-driven motivations (e.g., Hobolt and de Vries 2016).

Another important question is “what do citizens currently have in mind when thinking about European integration?” Traditionally, in many countries, pro-/anti-EU attitudes were aligned with immigration attitudes, while in other countries that were affected most by the Eurozone-wide economic crisis after 2009, they are increasingly tied to economic policies (Otjes and Katsanidou 2017). Future research might thus investigate to what extent personality predictors of EU attitudes resemble those of other (left–right) issue positions and whether or not they are actually contingent on the country context. Eventually, there is still much to be learned about the differentiation in EU attitudes or dimensionality (Boomgaarden et al. 2011). While we could not address the multi-faceted nature of EU attitudes in more detail (due to data limitations), we clearly elaborated on the explanatory variables side. It has yet to be studied whether or not personality domains and facets are differently associated with European identity, for instance.

Finding out which specific personality traits, such as the Big Five facets, matter the most for EU attitudes is also important for conducting future research. The results of this study could provide guidance on relevant moderators, for instance. This is particularly relevant when studying the impact of political communication, persuasion, and media effects, which might only apply for certain individuals. However, in lieu of extensive personality inventories, this might require that researchers also turn to the “nuances” captured by single items of commonly used personality scales (e.g., Mõttus et al. 2019).

Notes

The NEO Personality Inventory—Revised (NEO PI-R; see Costa and McCrae 1995) is perhaps the most widely used instrument in psychological research and clinical practice and covers 30 personality facets using 240 items.

In contrast, Curtis (2016) argues that the conflict-avoidant nature of agreeable individuals hampers European identification, because it might reinforce proclivities for the in-group.

Note that, ideally, one would have several indicators to also account for measurement errors in the dependent variable, which was unfortunately not possible.

This restriction was imposed in order to be able to identify the full model.

For model specifications and full output of the Mplus software, see the Online Supplemental Materials.

Note that the facets Respectfulness (A), Productiveness (C), Responsibility (C), Anxiety (N), and Energy Level (E) reflected mainly the variance of single items (see Online Supplemental Materials). In other words, the items supposedly measuring these facets do not share a common factor over and above the general domain factor and therefore the facet has little incremental validity (see Chen et al. 2012).

Modeling only the facets as first-order latent factors in SEM was not feasible and resulted in estimation problems, because the general domain factor is omitted and facets are by definition almost perfectly correlated (multicollinearity problem).

References

Aichholzer, J., D. Danner, and B. Rammstedt. 2018. Facets of personality and “ideological asymmetries”. Journal of Research in Personality 77: 90–100.

Bakan, D. 1966. The duality of human existence: An essay on psychology and religion. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Bakker, B.N., and C.H. de Vreese. 2015. Personality and European Union attitudes: Relationships across European Union attitude dimensions. European Union Politics 17: 25–45.

Bakker, B.N., and Y. Lelkes. 2018. Selling ourselves short? How abbreviated measures of personality change the way we think about personality and politics. The Journal of Politics 80: 1311–1325.

Boomgaarden, H.G., A.R. Schuck, M. Elenbaas, and C.H. de Vreese. 2011. Mapping EU attitudes: Conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support. European Union Politics 12: 241–266.

Chen, F.F., A. Hayes, C.S. Carver, J.P. Laurenceau, and Z. Zhang. 2012. Modeling general and specific variance in multifaceted constructs: A comparison of the bifactor model to other approaches. Journal of Personality 80: 219–251.

Costa Jr., P.T., and R.R. McCrae. 1995. Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment 64: 21–50.

Credé, M., P. Harms, S. Niehorster, and A. Gaye-Valentine. 2012. An evaluation of the consequences of using short measures of the Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102: 874–888.

Curtis, K.A. 2016. Personality’s effect on European identification. European Union Politics 17: 429–456.

Curtis, K.A., and J.H. Nielsen. 2018. Predispositions matter… but how? Ideology as a mediator of personality’s effects on EU support in five countries. Political Psychology 39 (6): 1251–1270.

Danner, D., B. Rammstedt, M. Bluemke, C. Lechner, S. Berres, T. Knopf, and O.P. John. 2019. Das Big Five Inventar 2: Validierung eines Persönlichkeitsinventars zur Erfassung von 5 Persönlichkeitsdomänen und 15 Facetten. Diagnostica 65: 121–132.

Donnellan, M.B., F.L. Oswald, B.M. Baird, and R.E. Lucas. 2006. The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment 18 (2): 192–203.

Easton, D. 1975. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457.

Federico, C.M., and A. Malka. 2018. The contingent, contextual nature of the relationship between needs for security and certainty and political preferences: Evidence and implications. Advances in Political Psychology 39 (S1): 3–48.

Gerber, A.S., G.A. Huber, D. Doherty, and C.M. Dowling. 2011. The Big Five personality traits in the political arena. Annual Review of Political Science 14: 265–287.

Hirsh, J.B., C.G. DeYoung, X. Xiaowen, and J.B. Peterson. 2010. Compassionate liberals and polite conservatives: Associations of Agreeableness with political ideology and moral values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36: 655–664.

Hobolt, S.B., and C.E. de Vries. 2016. Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science 19: 413–432.

Hu, L.T., and P.M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55.

Jost, J. T. 2017. Ideological asymmetries and the essence of political psychology. Political Psychology 38: 167–208.

McCrae, R.R. 2015. A more nuanced view of reliability: Specificity in the trait hierarchy. Personality and Social Psychology Review 19: 97–112.

Mõttus, R., J. Sinick, A. Terracciano, M. Hřebíčková, C. Kandler, J. Ando, and K.L. Jang. 2019. Personality characteristics below facets: A replication and meta-analysis of cross-rater agreement, rank-order stability, heritability, and utility of personality nuances. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 117: e35–e50.

Nielsen, J.H. 2016. Personality and Euroscepticism: The impact of personality on attitudes towards the EU. Journal of Common Market Studies 54: 1175–1198.

Nielsen, J.H. 2018. The effect of affect: How affective style determines attitudes towards the EU. European Union Politics 19: 75–96.

Onraet, E., A. Van Hiel, A. Roets, and I. Cornelis. 2011. The closed mind: ‘Experience’ and ‘cognition’ aspects of openness to experience and need for closure as psychological bases for right-wing attitudes. European Journal of Personality 25: 184–197.

Otjes, S., and A. Katsanidou. 2017. Beyond Kriesiland: EU integration as a super issue after the Eurocrisis. European Journal of Political Research 56: 301–319.

Paunonen, S.V., and M.C. Ashton. 2001. Big Five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 524–539.

Saris, W.E., and M. Revilla. 2016. Correction for measurement errors in survey research: Necessary and possible. Social Indicators Research 127: 1005–1020.

Schoen, H. 2007. Personality traits and foreign policy attitudes in German public opinion. Journal of Conflict Resolution 51: 408–430.

Sibley, C.G., and J. Duckitt. 2010. Personality geneses of authoritarianism: the form and function of openness to experience. In Perspectives on authoritarianism, ed. F. Funke, T. Petzel, J.C. Cohrs, and J. Duckitt, 169–199. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Soto, C.J., and O.P. John. 2017. The next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113: 117–143.

Westfall, J., and T. Yarkoni. 2016. Statistically controlling for confounding constructs is harder than you think. PLoS ONE 11 (3): e0152719.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers, Carolina Plescia, and Davide Morisi for comments on previous versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aichholzer, J., Rammstedt, B. Can specific personality traits better explain EU attitudes?. Acta Polit 56, 530–547 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00164-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00164-6