Abstract

The UK voted by a narrow margin to leave the European Union in a referendum on 23 June 2016. This article examines why this was the result and brings out comparative implications. Building on previous findings that expectations about the impact of Brexit were central to voters’ decisions, we seek to improve understanding of how these expectations mattered. On average across a range of issues, our analysis suggests that Leave would have won if voters had expected things to stay much the same following Brexit. A big exception is immigration, for which “no change” is associated with Remain voting. But there was a clear expectation that immigration would fall after Brexit (as most voters wanted). That consideration strengthened the Leave vote, and did so sufficiently to overwhelm a more important but less widely and strongly held expectation that the economy would suffer. We also find that those who were uncertain about where Brexit might lead were more likely to back the status quo. This supports a posited tendency towards status quo bias in referendum voting, notwithstanding a widespread belief that this bias failed to materialize in the Brexit vote. Our methods and findings have valuable implications for comparative research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Referendums on European matters take many forms. The Dutch referendum of April 2016 was a citizen-initiated vote on a relatively peripheral matter. The referendum held in the United Kingdom 11 weeks later was initiated by government and concerned the most fundamental EU question that could be asked in a single country: whether to remain a member. Despite this difference in structure, the outcome resembled that in the Netherlands: the European project and the bulk of the domestic political establishment were defeated. In the UK’s case, this was no minor inconvenience. It was the greatest policy failure for any UK government since the Suez crisis of 1956—indeed, at least one former prime minister said it was worse (The Scotsman 2016). It was also the greatest setback for the EU in the organization’s history. Its repercussions will likely dominate UK—and, to a lesser extent, EU—politics for years.

Existing studies have already shed considerable light on how this unexpected outcome came about. We seek here to build on that work, specifically by examining how expectations of the effects of the decision on Brexit affected voting. We adopt this focus for three reasons, which we elaborate in depth below. First, voters in the UK long held a largely instrumental view of EU membership, weighing it in terms of its perceived costs and benefits. This implies that voters’ decisions on whether to remain in the EU should have involved calculations of those costs and benefits too. Second, the comparative literature on referendum voting leads to the expectation that voting in a high-salience referendum such as this should have been strongly influenced by issue perceptions. Third, the emerging literature on the Brexit referendum itself supports the same conclusion.

We thus take a predominantly issue-based model as our focus. Moreover, the issues we expect mattered most and focus on are the prospective ones about the future outside as opposed to inside the EU. We consider what people’s expectations were about the consequences of leaving for a variety of social and economic outcomes, how these changed over the campaign, and how they affected voting.

In addition, while examining the effects of these expectations in general, we also give particular attention to one aspect of them: namely, uncertainty. That is, we look at the effects of not having clear expectations. We again do this for three reasons. First, politicians’ and campaigners’ assumptions about the effects of uncertainty were central to the real-world dynamics of the referendum. Specifically, campaigners on both sides assumed that uncertainty would lead voters to favour the status quo, which affected how they campaigned and, indeed, why Prime Minister David Cameron called the referendum in the first place. Second, the role of uncertainty in shaping the dynamics of opinion during referendum campaigns is an important but understudied aspect of referendums in general. Third, while this aspect of opinion formation has received attention in studies specifically of the Brexit referendum, we believe that this work has had major limitations. We adopt what we think is a methodologically innovative approach to take it further.

The first two sections of this article prepare the ground by elaborating upon the points set out in the preceding paragraphs. Section “Background: origins and dynamics of the Brexit referendum” explores the background to the 2016 Brexit referendum, focusing particularly on what it tells us about underlying opinion and expectations. Section “Explaining the referendum outcome” examines the comparative literature on referendum voting and the emerging literature on the Brexit referendum to build the foundations for our own expectations. It states hypotheses that we subsequently test. Section “Data” describes our data and methods. Section “Analysis” analyses these data, looking at how evolving expectations of the effects of remaining in or leaving the EU affected vote choice. Section “Conclusion” draws out conclusions and comparative implications.

We find that Remain campaigners lost, above all, because they failed to convince enough voters that leaving the EU would cause economic harm. By contrast, most voters did think Brexit would bring the benefit (as they saw it) of lower immigration. Voters who were uncertain of Brexit’s effects were more likely to support the status quo than those who thought Brexit would make no difference. Both our methods and our findings have important comparative implications.

Background: origins and dynamics of the Brexit referendum

Voters in the UK have long differed from those in most other European countries in their scepticism towards the EU and the “European project”. They have rarely thought themselves European, let alone believed in the vision of ever closer European integration: the annual British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey has never seen the proportion of respondents professing a European identity rise above one-sixth (Curtice 2016a, p. 11); the proportion wanting increased EU powers has been a sixth or lower in all years but one since 1998 (Curtice 2016a, p. 6). Most Britons have viewed EU membership as purely transactional.

As Evans et al. (2018) argue, this underlying Euroscepticism is important background for any analysis of the Brexit referendum. But it does not on its own explain why the referendum was called. While voters were sceptical of the EU, this was not an issue to which they devoted much attention. By the time David Cameron pledged to hold the referendum, in January 2013, the Ipsos MORI issues index, which asks respondents what the important issues facing Britain are, had not seen mentions of EU membership or powers hit double figures since June 2005—see the thick black line in Fig. 1. Only in 2016, as the referendum itself approached, did this issue rise to any prominence.

Source: Ipsos-MORI (2017)

Ipsos MORI Issues Index: Top Ten Issues, January 2005–November 2016. Notes: Ipsos-MORI asks two open-ended questions: ‘What would you say is the most important issue facing Britain today?’; and ‘What do you see as other important issues facing Britain today?’ Figures show the percentage of respondents giving a response falling within each category in response to either question. Ipsos-MORI divided the ‘Race relations/immigration/immigrants’ category in 2015 into ‘Race relations’ and ‘Immigration’. We have added these categories together in order to maintain continuity across years. The immigration category has varied between 34 and 56%; the race relations category has ranged from 0 to 7% (the highest figure being in July 2016, immediately after the referendum)

Rather, Cameron made his pledge in part because of hostility towards the EU within his own Conservative Party (Oliver 2016, pp. 9–10; The Economist 2013a) and in part under the impact of sections of public opinion as mediated through the party system. As Fig. 1 shows, while few voters took much interest in the EU per se, immigration (shown by the thick grey line) had long been a major concern, fuelled in part by high immigration from the East European countries that joined the EU in 2004. This fed rising support for the anti-EU UK Independence Party (UKIP), which averaged just over 10% across 27 polls completed in December 2012 (authors’ calculation from data in UK Polling Report 2017), compared to 3.1% in the 2010 general election (BBC News 2010). Many Conservatives saw this as a threat to their own electoral chances and “delighted in the prospect of spiking the guns of the UK Independence Party” through the referendum pledge (The Economist 2013a). Cameron may also have hoped that his pledge would limit any electoral threat from Labour, which faced a quandary in deciding whether to match it (The Economist 2013b).

Cameron’s pledge thus reflected the exigencies of managing his own party internally and seeking electoral advantage over competing parties. In addition, it emerged amidst a political discourse that for several decades had increasingly linked EU debates to the idea of holding some kind of referendum. Such referendum talk had first mushroomed in 1991–1992 during debates over the Maastricht Treaty. From 1997 onwards, all three main parties—the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats—had made EU-related referendum pledges in every one of their general election manifestos. Thus, by the time of David Cameron’s speech in January 2013, the idea of a referendum on the EU was familiar and easy.

The crucial final spur to Cameron’s pledge was his expectation that he would win the referendum. This expectation had two roots. First, the early polls put Remain ahead: across all the polls conducted between September 2015 (when the final wording of the referendum question was decided) and 20 February 2016 (when the referendum date was announced), Remain support (excluding don’t knows) averaged 53% (authors’ calculation from data at What UK Thinks 2017). Second, the government drew from past referendums the lesson that opinion tends to shift towards the status quo as polling day approaches.

Indeed, this was a key assumption made by campaigners, pollsters, and commentators across the board. Both campaigns assumed that voters—particularly swing voters—would be risk-averse. A diplomatic memo leaked a year before the referendum said Cameron “believes that people will ultimately vote for the status quo if the alternatives can be made to appear risky” (Nardelli and Watt 2015). Cameron’s Director of Communications says the Remain campaign “assumed the undecideds would turn to the status quo. … It had been the case at the general election and the pattern of the vast majority of referenda around the world. The reason for this is that the status quo is almost invariably the less risky option—the alternative, in our words, ‘a leap in the dark.’” Oliver (2016, p. 385). The Leave campaign, meanwhile, sought to undermine the idea that a Remain vote would simply preserve the status quo: the Chief Executive of Vote Leave, Matthew Elliott, says, “one of our key objectives in the campaign was to basically show the status quo wasn’t an option” (Bennett 2016, p. 294). Vote Leave’s key slogan—“Take back control”—was meant to evoke the idea of a return to something more secure (Cummings 2017). Leave campaigners pushed the possibility of Turkish EU membership and the creation of an EU army to promote the idea that staying in was a risk not worth taking (e.g. Bennett 2016, pp. 292–4). They even produced condoms printed with the slogans “The safe choice” and “It’s riskier to stay in” (Bennett 2016, p. 227).

Figure 2 shows the basic pattern of support for Remain as revealed in polls between September 2015 and referendum day. Three key features can be highlighted. First, while Remain generally led in the early polls, the size of that lead depended greatly on the polling method: telephone polls showed a very large advantage for Remain, while online polls showed a much more balanced race. The reasons for this difference were subject to much speculation and analysis (e.g. Curtice 2016b; Singh and Kanagasooriam 2016), but remain unclear. The divergence means we can be less certain about where opinion stood at the start of the campaign than we might hope. Second, there is no sign, in either polling mode, of any aggregate shift in opinion towards the status quo. Third, the two modes suggest different conclusions as to how far opinion in fact moved away from the status quo: telephone polls showed a large shift; online polls showed only a marginal change.

This overall pattern raises the question of whether the usual break towards the status quo among uncertain voters in fact failed to materialize. Campaigners certainly thought so. According to Oliver (2016, p. 385), the Remain campaign’s internal analysis concluded that, in the key swing voter groups, “a narrow majority thought that remaining was more risky. They believed that staying in the EU meant continued uncontrolled immigration and spending £350 million a week on the EU, not the NHS”. Dominic Cummings, Campaign Director of Vote Leave, says, “the now-mocked conventional wisdom that ‘the status quo almost always wins in referendums like this’ obviously has a lot of truth to it and it only proved false this time because of a combination of events that was improbable”. We shall examine below whether these interpretations are justified.

Explaining the referendum outcome

The comparative study of referendum voting has advanced considerably over the past quarter century. As it developed in the 1990s and early 2000s, this literature fell largely into two main camps. First, issue-based models posited that voters decide on the basis of their perceptions of the issues in the referendum question (e.g. Siune and Svensson 1993; Svensson 2002). Second, cue-based models proposed that voters decide on the basis of the “cues” provided by parties and politicians: either they treat cues as information shortcuts and vote with the politicians they trust (Lupia 1994), or they treat referendums as second-order contests and punish the politicians they dislike (Franklin et al. 1995). More recent research typically blends these approaches: issue voting tends to grow the higher the salience of the issue in question; cues gain importance as salience falls (e.g. Franklin 2002; Garry et al. 2005; Hobolt 2009; Hobolt and Brouard 2011; Schuck and De Vreese 2008; Svensson 2007; for an overview, see Renwick 2017, pp. 443–448).

Brexit was clearly an exceptionally salient issue, producing the highest turnout in a UK-wide vote for almost a quarter of a century. This leads us to posit that issue voting should have mattered.

The emerging literature on the Brexit referendum itself supports this hypothesis. That literature is already rich. Some authors focus on particular factors: Eurosceptic attitudes (Evans et al. 2018); concerns about immigration (Goodwin and Milazzo 2017); divisions between those who attended university and others (e.g. Evans and Tilley 2017, pp. 201–206); voting among traditional white working class voters who feel neglected by the main parties (Ford and Goodwin 2017); and economic deprivation and insecurity (Becker et al. 2017; Halikiopoulou and Vlandas 2018). Other studies that examine the impacts of a broad range of potential causal factors are particularly instructive. Clarke et al. (2017, p. 456) argue that a combination of factors were relevant for the Brexit referendum, but that issue-based cost/benefit assessments were most important. Hobolt (2016) tests four models of the determinants of the vote and finds the issue voting model to have the highest explained variance (pseudo R-squared), suggesting that issue voting was “the most proximal cause of vote choice” (Hobolt 2016, p. 1270). Curtice (2017a) conducts a similar exercise and concludes that both issue voting and identity-based voting mattered. On the former, he says:

Of all the variables that were potential candidates for inclusion in our model, the perceived impact of leaving the EU on the economy proved to be the variable that was most strongly related to how people voted, and it remained strongly related even after the inclusion of other variables. Those who thought the economy would suffer as a result of leaving the EU were much less likely to vote to leave the EU than were those who thought it would be strengthened. (Curtice 2017a, p. 31).

These findings further ground our initial expectation, that issue voting mattered and that investigating further its internal workings is worthwhile.

As we noted in outlining the background to the Brexit referendum, one aspect of issue voting that particularly mattered to politicians and campaigners was the belief that uncertainty breeds caution and tends to produce a shift towards the status quo as voters’ minds focus with increasing seriousness on the choice before them. Such beliefs are widespread among political activists in many countries, and as such deserve careful analysis. So far, however, they have received only limited attention from political scientists. In a study of the UK’s previous national referendum—a vote on the electoral system in 2011—Whiteley et al. (2013) posited a tendency for opinion to shift towards the status quo; they christened this pattern “LeDuc’s Law”, attributing its identification to LeDuc (2003). In fact, however, LeDuc stated no such general pattern, emphasizing, rather, the unpredictability of opinion change during referendum campaigns (LeDuc 2003, p. 165). Clarke et al. return to this theme in their study of the 2016 referendum. They posit:

Prior to the beginning of a referendum campaign sizable numbers of people tell pollsters that they support the change being proposed. But, as the campaign progresses and decision day nears, some have misgivings, reconsider and, after a period of indecision, end up voting to keep things as they are. (Clarke et al. 2017, p. 445)

They test this through a measure of voters’ perceptions of the riskiness of leaving the EU, ranging from 0 (“not risky”) to 10 (“very risky”). We have profound misgivings about this, however, as a way to test a hypothesis about uncertainty. Respondents who thought leaving the EU “very risky” were not uncertain: rather, they were very confident that Brexit posed major dangers. We therefore develop an alternative approach below. This focuses specifically on voters who said they were uncertain as to what the effects of Brexit would be.

In sum, taking our cue from campaigners, comparative political scientists, and students of the Brexit referendum itself, we focus mainly on issue-based voting. Our main contribution to the debate on voting at the Brexit referendum is not to establish that issue voting mattered but to elucidate how it mattered. We focus particularly on voter expectations about the consequences of leaving, uncertainty in those expectations, and how those things changed over the campaign.

The theoretical analysis above, combined with the findings of existing studies of the Brexit referendum, leads us to formulate four hypotheses:

H1

Expectations of the effects of Brexit influence voting: an expectation of a harmful effect boosts support for Remain, and vice versa.

H2

Those who are uncertain of the effects of Brexit are more likely to support the status quo than those who think Brexit will have no effect.

H3

This uncertainty should fall as the campaign proceeds and voters receive more information.

H4

If their indecision is rooted in uncertainty, voters who are undecided between Leave and Remain should ultimately opt for the status quo. But their indecision could also derive from indifference, leading to no expected skew either way.

We do not, however, make hypotheses about the content of people’s expectations: these are to be discovered through empirical analysis. While the discussion above of the background to the referendum leads to some hunches in this respect—such as that most UK voters would likely be sceptical of any positive effects of EU membership—we confine our hypotheses to points that are theoretically grounded.

Data

We use the British Election Study (BES) internet panel, administered by YouGov. This is a multiwave panel study that started in 2014 and continued beyond the referendum. The main waves of interest here are the pre-referendum campaign wave 7 (14th April—4th May 2016), the rolling campaign wave 8 (6th May—22nd June), and the post-referendum wave 9 (24th June—4th July 2016). The rolling campaign wave 8 involved daily random samples allowing us to analyse the dynamics of opinion over the final 2 months of the campaign.

Given what we have seen about the divergence between telephone and online polls, the fact that the BES uses an online panel is likely to affect our conclusions. While relative support for Remain over Leave declined during the campaign for both kinds of polls, the trend was much more dramatic in telephone polls, especially over the final 2 months that are our main focus. Self-selected online panels have disproportionately highly politically engaged respondents who may have formed opinions early and been relatively unlikely to change them. This might be particularly the case for the BES panel for which half the wave 7 and 8 respondents also completed all of waves 1–6: they had been willing to complete eight lengthy questionnaires on politics in 2 years. The panel data are thus likely to understate the degree of change. There are no telephone polls with repeated questions during the final 2 months on perceptions of the consequences of Brexit with which we can compare our findings. Still, it is comforting that the trends in the online and telephone poll vote intention figures are in the same direction and that the error in the final online polls was smaller than in the telephone polls.

Thinking of the referendum decision as a cost/benefit calculation, it matters what people thought would happen if Britain left compared with remaining in the EU. So we focus on questions asked in waves 7 and 8 of the BES about expectations of the potential effects of leaving the EU on ten specific dimensions:

-

Regarding working conditions for British workers, the general economic situation in the UK and “my personal financial situation”, respondents were asked “Do you think the following would be better, worse or about the same if the UK leaves the European Union?” The response options were on a five-point scale from “much worse” to “much better”.

-

Regarding unemployment, international trade, immigration to the UK, the risk of terrorism and Britain’s influence in the world, the question was “Do you think the following would be higher, lower or about the same if the UK leaves the European Union?” Again there was a five-point response scale, this time from “much lower” to “much higher”.

-

Finally, respondents were asked “If the UK *leaves* the European Union, how much more likely is it that big companies would leave the UK” and a similar question about the likelihood that “Scotland would leave the UK”. The five-point response scale for these questions ran from “much less likely” to “much more likely”.

For the regression models below, these questions were re-centred on a zero mid-point meaning “about the same”. Our key methodological innovation is that, in order to model the effects of voters’ uncertainty about the impact of Brexit, we use separate dummy variables to indicate Don’t Know responses to these questions. This is, we think, an innovative approach, and it allows a more nuanced analysis of this issue than in any previous referendum study.

One concern about expectations questions such as these is that responses will primarily reflect the cognitive biases of those who have already decided what side they are on. Responses on different items are often correlated, suggesting some such bias (cf. Evans et al. 2018, p. 390). But not all the items are correlated with each other. For two of the main ones, the economy and immigration, there is a reasonable but not strong correlation: − 0.31 excluding Don’t Knows. This suggests that respondents were maybe somewhat, but not solely, giving patterned responses reflecting their partisan and Eurosceptic/Europhile propensities. For this reason, and because we are interested in the relative importance of different issues, we do not combine the items into composite indices as Clarke et al. (2017) and Evans et al. (2018) do.

Since one of our hypotheses is that people may have been more inclined to support the status quo because of uncertainty, we also consider responses to the question, “How sure are you about what would happen to the UK if it left the EU or if it remained in the EU?” Responses for both Leave and Remain were on a scale of very unsure, quite unsure, quite sure, to very sure.

Control variables are detailed in the notes to tables. They are collectively more comprehensive than those in previous research. There are some different operationalizations but they effectively encompass all the main findings in Hobolt (2016), Curtice (2017a) and Clarke et al. (2017). Overall the choice of control variables made little difference to our results.

Analysis

We analyse the evidence in four steps. First, we describe perceptions of the consequences of Brexit in the early stages of the campaign (wave 7). We made no hypotheses about this above, but treat it as a matter for empirical determination. Second, we assess whether these perceptions affected vote intention, taking account both of positive/negative perceptions (H1) and of uncertainty (H2). Third, we examine how perceptions changed between waves 7 and 8 and over the final 2 months of the campaign (wave 8). Again, we have not formulated hypotheses for this, except that uncertainty should have fallen (H3). Finally, we analyse what the post-referendum survey tells us about the impact of perceptions of Brexit’s consequences on vote decision at the end of the campaign, allowing us to return to H1 and H2, and to consider how previously undecided voters made up their minds (H4).

What did people think the consequences of Brexit would be?

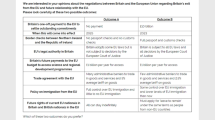

Table 1 shows that, in the early stages of the campaign, people thought little would change if the UK left the EU. This is true of all the issues asked about except the chances of Scottish independence (thought to be more likely) and immigration (thought likely to fall). For all the other outcomes, “about the same” was the modal response, and the balance of opinion was fairly even. On the economic issues the average view was typically that things would get worse but not by much, and not many more thought this than thought things would get better. The balance of opinion on economic issues only marginally favoured Remain, but that on immigration strongly favoured Leave: most people wanted immigration to fall; only 17% wanted it to rise.

How did perceptions about the consequences of Brexit affect vote intention?

Table 2 shows two logistic regressionsFootnote 1 of intention to vote Leave instead of Remain in wave 7 as a function of responses to the questions listed above about what would happen if Britain left the EU. Both models include Don’t Know responses to the expectations questions as separate dummy variables. The first model is without controls, while the second includes sociodemographic and attitudinal controls and a lagged-dependent variable (wave 6 vote intention). Here and in later tables, introducing controls substantially reduces the available sample size, but Model 1 coefficients barely change if fitted using the same cases as for Model 2 (results not shown).

By comparison with a model using sociodemographic controls only (not shown), inclusion of attitudinal control variables (such as government approval and leader evaluations) increases the R-squared by 0.07 and does not change the general pattern of coefficient size and direction. This implies that issue-based considerations either were much more important than or at least mediated the effects of more general political attitudes. More broadly, the fact that the coefficients of the expectation terms do not change much after inclusion of controls provides strong evidence that there is a causal effect from expectations to vote choice rather than responses to the expectation questions merely reflecting the vote intention.Footnote 2

With so many expectations questions of the same form that are cognitively demanding we might expect substantial multicollinearity problems. Instead, it is remarkable that all the questions operate in the expected direction and that all but one (on Scottish independence) are statistically significant. All of this fits strongly with H1.

The broad pattern of coefficients fits with research suggesting that the economy and immigration were the main issues (Curtice 2017a). The immigration question has a negative effect because most people want immigration to fall. For the few who want greater immigration there was no statistically significant relationship. Also, beliefs about economic consequences are more important the more the respondent approved of the government. Other sensible interaction effects have also been identified in further analysis, but they are not shown because none affect the overall fit of the model considerably.Footnote 3 That perceptions on so many issues work in theoretically prescribed ways further indicates a strong cognitive basis to the referendum vote: as expected, issue voting mattered.

Model 1 in Table 2 also tells us about the political consequences of those perceptions. As we said above, we re-centred the expectation questions so that 0 corresponds to the “about the same” response category (or equivalent). The intercept for model 1 of 11 suggests that, had everyone in late April 2016 thought that leaving the EU would leave all the factors mentioned unchanged, Leave would have won 53% of the vote.Footnote 4 In fact, the 1% of respondents who actually said little would change to all the questions mainly voted Remain. But this was because those who thought immigration rates would not change were strongly Remain. Since the model intercept essentially averages across issues it does not let this feature of the immigration question responses totally dominate. So we should interpret the intercept as meaning that people would marginally have preferred to leave the EU if they thought it would make little social or economic difference to their lives on average across the set of issues. This accords with the view that Britain’s membership of the EU has long been fundamentally transactional, sustained by the perception of benefits being greater than the costs.Footnote 5

Still, 53% would have been a close result. To win comfortably each side needed to develop some kind of advantage in perceived costs and benefits of leaving versus remaining. The online polls at the time of wave 7 were showing a neck-and-neck race (see Fig. 2) and the overall BES wave 7 vote intention question had Leave on 49% (after excluding Don’t Knows). Since this figure is relatively close to the intercept of model 1, public expectations for Brexit, taking account of the relative importance of the different issues, must have been balanced only slightly in favour of Remain.

We turn now to H2, relating to uncertainty. For all but three of the issues in Table 2, the coefficient of Don’t Know is negative. Although they are often statistically insignificant (especially in model 2), this is due to multicollinearity, and their cumulative impact means that those who were unclear what they thought would happen were more inclined to support the status quo than if they had thought more confidently that Brexit would not change much. This fits with the hypothesis that uncertainty leads people towards the status quo.

This interpretation of the coefficients of “Don’t Know” indicator variables is further supported by the models in Table 3, which consider the direct questions in wave 7 about certainty over what would happen in the events of a Leave or Remain vote. More certainty about what would happen if Leave won is associated with more Leave voting and similarly with respect to Remain. Model 2 shows the effects are diminished but robust to controlling for all the variables in Table 2 model 2.

How did perceptions of the consequences of Brexit change over the final three months?

Having analysed perceptions of Brexit and voting intentions at the start of the campaign, our next step is to consider how these changed over the course of the referendum campaign. As before, we do not, for the most part, have prior hypotheses about the content of people’s expectations: whether people changed their minds about what they thought the consequences of Brexit would be is a matter for empirical examination.

As it turns out, both analysis of changes from wave 7 to wave 8 and analysis of trends within wave 8 suggest that expectations changed somewhat, but not much. With the exception of trade, between waves 7 and 8, people generally became more likely to believe that Brexit would have negative economic consequences and that immigration would fall. To this extent they increasingly believed the main planks of both the Leave and Remain campaigns.Footnote 6 It was not simply that prior supporters of both sides strengthened their views on the issues that most advantaged their side: expectations about the economy and personal finances following Brexit worsened for both Remain and Leave supporters. But the changes were modest. The largest was on the economy in general, but that was just a 0.07 drop in the mean on the five-point scale. There were no significant changes between waves 7 and 8 in perceived consequences for the risk of terrorism, Scottish independence or British influence abroad. This fits with the view that the campaign messaging during the final 2 weeks was dominated by immigration and economic issues (Shipman 2016).

Figure 3 shows the patterns of change for selected itemsFootnote 7 during wave 8. Again, there is very little change, but there is some. The fact that the patterns are not all the same, both between waves 7 and 8 and within wave 8, suggests that people were reflecting on the issues separately and that their responses were not simply the product of some latent propensity to support or oppose Brexit, as suggested by Clarke et al. (2017) and Evans et al. (2018).

Most lines show trendless fluctuations. For instance, the perceived consequences of Brexit for the NHS started positive and became more so but then dropped in the final 2 weeks. One or two have more noticeable trends, but they were not cumulatively to either side’s advantage. Remain’s advantage on international trade was neutralized, but the perceived consequences of leaving the EU for the economy as a whole got slightly worse. Overall there was little change, and so it mattered far more that opinion as to whether things would get better or worse was fairly balanced on most issues—except immigration, where there was consensus that it would drop on leaving the EU.

Our one prior hypothesis regarding the content of people’s Brexit expectations related to uncertainty: since campaigns are supposed to inform people, we posited a decline in the numbers saying they did not know what would happen in the event of a Leave vote (H3). It turns out that, indeed, on each issue there was a small drop of around a percentage point from wave 7 to wave 8 in the number of Don’t Knows. However, the consistency of the size of the drop and the trends over wave 8 across issues are so strong that it seems implausible that this was due to information and learning. That mechanism should have led to greater declines in Don’t Knows for some issues (perhaps those most discussed or those previously neglected) than others. Instead, it looks like there was simply a tendency for those who responded later in the campaign to be slightly less likely to say Don’t Know across all items.

Similarly, there was an improvement in self-reported certainty between waves 7 and 8. The percentage saying they were at least “quite sure” what would happen increased by 8 points when asked about a Leave win, and by five-points for a Remain win. However, there was no systematic trend in self-reported certainty as to what would happen for either outcome over the final 2 months. Overall then, there is little sign, notwithstanding H3, that the final 3 months of the campaign substantially improved voters’ perceived knowledge of the effects of either side winning. This is perhaps because the campaign added as much confusion as information, or because voters learnt that their prior uncertainty was well founded. But we should remember that this may be because the BES panel were already fairly well informed early on.

How did expectations at the end of the campaign influence the final vote?

We finally consider how changing expectations affected voting. Table 4 mirrors Table 2 in structure, but this time the dependent variable is the recall vote from the post-referendum wave 9 survey. The main expectation variables in both models are those from wave 8, instead of 7. Model 2 of Table 4 includes sociodemographic and attitudinal controls,Footnote 8 lagged vote intention and lagged perceptions of the consequences of a Leave vote. The latter are included to provide a still more rigorous test of the causal relationship posited in H1. If the eventual vote choice was influenced by changing opinion during the campaign, the wave 8 expectations should be much more powerful predictors than the wave 7 expectations. That is precisely what we see. Had responses to the expectation questions just been noisy reflections of prior Euroscepticism then the wave 7 expectations should also be good predictors, or both should be weak because of multicollinearity. But that is not what the model shows. Modest though the changes in perceptions of the consequences of Brexit were, they clearly affected the eventual vote.

Comparing model 1 in Table 2 with model 1 of Table 4, we see broadly similar magnitudes of coefficients for the main variables. This suggests the (relative) importance of the issues changed little.

With regard to uncertainty (H2), the effects of saying Don’t Know are slightly changed in Table 4 compared with Table 2 depending on the issue, but not systematically and they are still mainly negative.Footnote 9 The main tendency was for uncertainty over the consequences still to be associated with Remain voting, as expected.

Looking at those who responded to the BES in the final 2 weeks of the campaign suggests that Leave won the campaign modestly. This fits with the trend in the opinion polls in Fig. 2. Among those who responded to wave 8 in the final fortnight, 4% switched from Remain in April to Leave in June, but only 2% switched the other way. Such switching was related to perceived consequences of Brexit. Those moving from Leave to Remain tended to have become more convinced of the negative economic consequences of leaving and less convinced that immigration would fall. The reverse is true of those who switched the other way. Those who changed their vote changed their expectations in a corresponding direction and much more than those who did not change their vote intention. Perhaps most telling is the extent to which those who switched from Remain to Leave simultaneously took a much more favourable opinion of the economic consequences of leaving. This suggests primarily a failure of the Remain campaign to persuade swing voters of their main argument.

While vote switching between April and June was more towards Leave, the BES data also suggest that between the final few days of the campaign and the vote there was a small late swing to Remain of about 1 percentage point. While this is too modest to claim that there was reversion to the status quo, equally there is no support for the notion that undecided voters came to perceive Leave as the safer option.

Our final hypothesis, H4, supposes that the eventual vote choice of those who were previously undecided would depend on the source of their indecision. The confirmation of H2 in Table 4 suggests that those who did not know which side to vote for late in the campaign because they were uncertain as to the consequences of Brexit would be more likely, if they did vote, to support Remain on referendum day. Overall those who were still undecided in the final 2 weeks but did nevertheless vote split 53:47 for Remain. The split was more favourable for Remain the more frequently they responded “Don’t Know” to the expectations questions, but because of small numbers, not statistically significantly so.

Conclusions

We can draw out conclusions from the preceding analysis regarding two broad questions. First, what do we learn about this referendum in particular—about why Leave won the 2016 Brexit referendum? Second, what do we learn about referendum dynamics in general—what are the implications of the present analysis that deserve to be studied comparatively?

Regarding the first question, Leave won only narrowly, so many factors with very small effects could have determined the outcome. Such factors include many variables we have not discussed here, including partisanship, leader evaluations, ideology, and turnout. There is little sense in trying to single out any one thing as decisively switching the result.

But we can say that most of those factors appear to have been at least mediated by expectations about the consequences of leaving the EU. These expectations were the most powerful and proximate factors affecting vote choice, regardless of whether they were based on accurate or misleading sources.

Supporting the view that UK voters see EU membership in purely instrumental terms, our analysis shows that Leave would have won if the public thought little change would result from leaving the EU. That is, however, on average across a range of issues. Immigration is a big exception, on which those who thought that rates of net in migration would be just as high after Brexit were likely to vote Remain.

Economic issues were the most important factor for the public. The key question is not why the public did not care enough about the economic consequences to generate a Remain victory, but why they did not sufficiently believe that the consequences would be negative: the public were much clearer that immigration would fall than that the economy would suffer in the event of a Leave vote. Had people expected economic harm from Brexit as much as they expected falling immigration, the UK would have voted strongly to Remain. The Leave vote was primarily based on the expectation that Brexit would reduce immigration—a conclusion also supported by analysis of high-quality face-to-face probability sample data (Curtice 2017b).

Over the course of the campaign people became more likely to believe both that Brexit would have negative economic consequences and that immigration would fall. But overall, we see little evidence that voters’ confidence that they understood the consequences of Brexit rose substantially. In this sense, the campaign failed. As expected—and in contrast to the post-referendum conclusions of campaigners—voters who were uncertain about the consequences of Brexit were more likely to back the status quo than were voters who thought Brexit would make little difference.

These findings help to elucidate the dynamics of opinion in the Brexit referendum. As indicated by our second question, they are also of much broader comparative significance. Our conclusion that issues mattered in this vote (in line with H1) is not surprising: it further supports existing comparative evidence that issue voting matters in high-salience referendums. More original are our insights regarding uncertainty (H2). Though it is widely presumed that uncertainty about the consequences of a referendum decision generates support for the status quo, we believe that our approach to modelling voters’ uncertainty offers the first rigorous examination of this proposition. We see clear support for the proposition in the Brexit referendum. This should be a topic for further comparative research in the future.

There is also scope for further consideration of how different issues and expectations matter in conjunction with each other as opposed to independently, and how they may matter differently for different kinds of people. For instance, we noted earlier that government supporters put more weight on economic considerations, but it is not clear why. It could be that, by emphasizing economic consequences, the government raised the salience of the economy more among its own supporters, but it could also be that Conservative voters tend to be more concerned about macroeconomic outcomes than issues such as worker’s rights. There are also other possible explanations. Puzzles such as this deserve further investigation. Here, we hope we have adequately shown that voter expectations, and the lack of them, matter, even across a wide range of different economic and social outcomes.

Notes

See, for example, Long and Freese (2005) for model equations. Linear probability regression models, here and later, give qualitatively very similar results. More detailed analyses with all the expectation questions treated as factor variables show that there are deviations in the linearity of relationships, but that all relationships are monotone. We present the models assuming linearity because they are much more parsimonious. Our conclusions would be stronger, if anything, with full categorization of explanatory variables.

A further even stronger test uses wave 8 data with which we can include lagged values of the expectations variables as well as lagged vote intention and socio-demographics. Such an analysis in effect shows that individual-level changes in perceptions are associated with vote intention, in the direction expected, for nearly all variables.

For instance, expectations about the consequences for the rights of British workers matter more for those who want more redistribution.

Note that the intercept for model 2 cannot be so interpreted because of the lagged dependent variable and controls.

The version of the model with expectations as factor variables (in footnote 1) suggests an even stronger Leave advantage of 55% among those who thought things would stay much the same after Brexit.

Note that this implies that people were not just becoming more favourable to one side and so adjusting their perceptions to fit their vote intention. Further analysis of the correlations between individual-level change on different items shows a complex pattern.

The NHS item was not asked in wave 7.

As for the analysis in Table 2, the attitudinal control variables make barely any difference to the coefficients of the expectation variables.

Immigration appears to have become a case where being unclear about the consequences of Brexit was associated with more Leave voting, but this needs to be understood relative to the high Remain vote for those who thought that immigration levels would not change after Brexit (Curtice 2017b).

References

BBC News. 2010. Election 2010—National Results. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/election2010/results/. Accessed 2 March 2017.

Becker, S.O., T. Fetzer, and D. Novy. 2017. Who Voted for Brexit? A Comprehensive District-Level Analysis. Economic Policy 32 (92): 601–650.

Bennett, O. 2016. The Brexit club: The inside story of the leave campaign’s shock victory. London: Biteback.

Clarke, H.D., M. Goodwin, and P. Whiteley. 2017. Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cummings, D. 2017. How the Brexit Referendum Was Won. The Spectator (Online), 9 January. Accessed 3 April 2018.

Curtice, J. (2016a) How Deeply Does Britain’s Euroscepticism Run? London: NatCen. British Social Attitudes Report no. 33

Curtice, J. 2016b. Are Phone Polls More Accurate than Internet Polls in the EU Referendum? What UK Thinks blog, 30 March. http://whatukthinks.org/eu/are-phone-polls-more-accurate-than-internet-polls-in-the-eu-referendum/. Accessed 12 March 2017.

Curtice, J. 2017a. Why Leave Won the UK’s EU Referendum. Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (S1): 19–37.

Curtice, J. 2017b. The Vote to Leave the EU: Litmus Test or Lightening Rod? http://bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/39149/bsa34_brexit_final.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2017.

The Economist. 2013a. Hero for a Day (Bagehot). 26 January.

The Economist. 2013b. The Gambler. 26 January.

Evans, G., N. Carl, and J. Dennison. 2018. Brexit: The Causes and Consequences of the UK’s Decision to Leave the EU. In Europe’s Crises, ed. M. Castells, O. Bouin, J. Caraça, G. Cardoso, J.B. Thompson, and M. Wieviorka, 380–404. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Evans, G., and J. Tilley. 2017. The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ford, R., and M. Goodwin. 2017. Britain After Brexit: A Nation Divided. Journal of Democracy 28: 17–30.

Franklin, M.N. 2002. Learning from the Danish Case: A Comment on Palle Svensson’s Critique of the Franklin Thesis. European Journal of Political Research 41 (6): 751–757.

Franklin, M.N., C. van der Eijk, and M. Marsh. 1995. Referendum Outcomes and Trust in Government: Public Support for Europe in the Wake of Maastricht. West European Politics 18 (3): 101–117.

Garry, J., M. Marsh, and R. Sinnott. 2005. ‘Second-Order’ versus ‘Issue-Voting’ Effects in EU Referendums: Evidence from the Irish Nice Treaty Referendums. European Union Politics 6 (2): 201–221.

Goodwin, M., and C. Milazzo. 2017. Taking Back Control? Investigating the Role of Immigration in the 2016 Vote for Brexit. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (3): 450–464.

Halikiopoulou, D. and Vlandas, T. 2018. Economic Insecurity and the Brexit Vote. In: B. Leruth, N. Startin, and S. Usherwood (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism. Abingdon: Routledge, ch. 34 (no page numbers).

Hobolt, S.B. 2009. Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hobolt, S.B. 2016. The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent. Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1259–1277.

Hobolt, S.B., and S. Brouard. 2011. Contesting the European Union? Why the Dutch and the French Rejected the European Constitution. Political Research Quarterly 64 (2): 309–322.

Ipsos MORI. 2017. Issues Index Archive. https://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/2420/Issues-Index-Archive.aspx. Accessed 1 March 2017.

LeDuc, L. 2003. The Politics of Direct Democracy: Referendums in Global Perspective. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press.

Long, J.S., and J. Freese. 2005. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 2nd ed. Texas: Stata Press.

Lupia, A. 1994. Shortcuts Versus Encyclopedias: Information and Voting Behavior in California Insurance Reform Elections. American Political Science Review 88 (1): 63–76.

Nardelli, A. and Watt, N. 2015. David Cameron Plans EU Campaign Focusing on ‘risky’ Impact of UK Exit. The Guardian (Online), 26 June. Accessed 5 April 2018.

Oliver, C. 2016. Unleashing Demons: The Inside Story of Brexit. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Renwick, A. 2017. Referendums. In The Sage Handbook of Electoral Behaviour, ed. K. Arzheimer, J. Evans, and M. Lewis-Beck, 433–458. London: Sage.

Schuck, A.R.T., and C.H. de Vreese. 2008. The Dutch No to the EU Constitution: Assessing the Role of EU Skepticism and the Campaign. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 8 (1): 101–128.

The Scotsman. 2016. “Brexit is worse than Suez, says Gordon Brown”. 29 June. https://www.scotsman.com/news/uk/brexit-is-worse-than-suez-says-gordon-brown-1-4165195. Accessed 14 April 2018.

Shipman, T. 2016. All Out War: The Full Story of How Brexit Sank Britain’s Political Class. London: William Collins.

Singh, M. and Kanagasooriam J. 2016. Polls Apart: An Investigation into the Differences between Phone and Online Polling for the UK’s EU Membership Referendum. Populus and Number Cruncher Politics report, March. http://www.populus.co.uk/2016/03/polls-apart/. Accessed 12 March 2017.

Siune, K., and P. Svensson. 1993. The Danes and the Maastricht Treaty: The Danish EC Referendum of June 1992. Electoral Studies 12 (2): 99–111.

Svensson, P. 2002. Five Danish Referendums on the European Community and European Union: A Critical Assessment of the Franklin Thesis. European Journal of Political Research 41 (6): 733–750.

Svensson, P. 2007. Voting Behaviour in the European Constitution Process. In Direct Democracy in Europe: Developments and Prospects, ed. Z. Pállinger, B. Kaufmann, W. Marxer, and T. Schiller, 163–173. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

UK Polling Report. 2017. Voting Intention since 2010. http://www.ukpollingreport.co.uk/voting-intention-2. Accessed 2 March 2017.

What UK Thinks. 2017. Referendum Vote Intention Poll of Polls. http://whatukthinks.org. Accessed 12 March 2017.

Whiteley, P., H.D. Clarke, D. Sanders, and M.C. Stewart. 2013. Affluence, Austerity, and Electoral Change in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fisher, S.D., Renwick, A. The UK’s referendum on EU membership of June 2016: how expectations of Brexit’s impact affected the outcome. Acta Polit 53, 590–611 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0111-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0111-3