Abstract

International business scholars have recognized the impact of political and economic nationalism on the multinational enterprise (MNE). We complement these approaches by highlighting the sociological manifestations of nationalism and their implications for the MNE. We argue that nationalist sentiments, i.e., widely shared assumptions of superiority over other nations and cultures, constitute an under-researched but critical element in international business (IB). Drawing insights from organizational sociology, we elucidate how nationalist sentiments manifest in the MNE’s external and internal environment. Specifically, we suggest that nationalist sentiments accentuate national institutional logics, generate status-based categorizations of foreign and domestic firms, and heighten emphasis on national organizational identities. These manifestations impact the MNE’s operations by limiting room for hybridization of dissimilar practices and routines, increasing the risk of discrimination and stereotyping by local audiences, and entrenching resistance to foreign ideas and practices among organizational members. We suggest that MNEs have three strategic choices in responding to nationalist sentiments: avoid their manifestations, mitigate their implications, or leverage nationalist sentiments to the MNE’s advantage. In sum, our framework provides a starting point for IB scholars to examine the strategic implications of nationalist sentiments for the MNE.

Plain language summary

Recent years have seen a resurgence of nationalism – a sense of pride and superiority tied to one's own nation. This trend has significant implications for multinational enterprises (MNEs) companies that operate in multiple countries) and across different cultures. While previous research has explored the impact of political and economic nationalism on MNEs, there is a gap in understanding the effect of societal-level nationalist sentiments – personal beliefs and attitudes about national superiority expressed in daily life. This article contributes to filling this gap by discussing the impact of nationalist sentiments and how MNEs can respond. This article incorporates insights from organizational sociology to discuss how nationalist sentiments can emphasize national logics (the values and societal traits that form national identity), reinforce status differences between foreign and domestic companies, and increase emphasis on the MNEs’ national organizational identity. The paper is conceptual, meaning it develops a theoretical framework rather than conducting experiments or collecting data. The work helps us understand how MNEs can manage operations effectively across countries, when nationalist sentiments vary. The authors suggest that nationalist sentiments can restrict the blending of practices, lead to discrimination and stereotyping of foreign MNEs, and cause resistance to foreign elements within MNEs. They also discuss strategies MNEs can use to avoid, reduce, or leverage these effects. For instance, MNEs might avoid markets with strong nationalist sentiments, work to alter negative stereotypes, or highlight their national identity to gain competitive advantages. The paper argues that nationalist sentiments can significantly shape the strategies and operations of MNEs. It suggests that MNEs need to develop effective strategies in response to societal-level nationalism in the countries they operate in. The potential impact of this work is significant, as it can guide MNEs in navigating the complexities of international business in an era where nationalism is on the rise. This text was initially drafted using artificial intelligence, then reviewed by the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Résumé

Les chercheurs en affaires internationales ont reconnu l'impact du nationalisme économique et politique sur les entreprises multinationales (Multinational Enterprise - MNE). Nous complétons ces approches en mettant en lumière les manifestations sociologiques du nationalisme et leurs implications pour les MNEs. Nous argumentons que les sentiments nationalistes, c'est-à-dire les suppositions largement partagées de supériorité par rapport à d'autres nations et cultures, constituent un élément cardinal mais pourtant sous exploré dans la recherche en affaires internationales. Nous appuyant sur la sociologie des organisations, nous expliquons comment les sentiments nationalistes se manifestent dans l'environnement externe et interne de la MNE. Plus précisément, nous suggérons que les sentiments nationalistes accentuent les logiques institutionnelles nationales, génèrent des catégorisations basées sur le statut des entreprises étrangères et nationales, et mettent l'accent sur les identités organisationnelles nationales. Ces manifestations ont un impact sur les opérations de la MNE en limitant les possibilités d'hybridation de pratiques et de routines différentes, en augmentant le risque de discrimination et de stéréotypes de la part des publics locaux et en enracinant la résistance aux pratiques et idées étrangères parmi les membres de l'organisation. Nous suggérons que les MNEs ont trois choix stratégiques pour répondre aux sentiments nationalistes : éviter leurs manifestations, atténuer leurs implications ou exploiter des sentiments nationalistes à l'avantage de la MNE. En résumé, notre cadre apporte aux chercheurs en affaires internationales un point de départ pour examiner des implications stratégiques des sentiments nationalistes pour la MNE.

Resumen

Los académicos de negocios Internacionales han reconocido el impacto del nacionalismo en la empresa multinacional (EMN). Complementamos esos enfoques resaltando las manifestaciones sociológicas de nacionalismos y sus implicaciones para la EMN. Discutimos que el sentir nacionalista, es decir, la suposición ampliamente compartida de superioridad sobre otras naciones y culturas constituye un elemento crítico, pero poco estudiado en negocios internacionales (NI). Basándonos en los aportes de la sociología organizacional, ponemos de manifiesto como el sentir nacionalista se manifiesta en el entorno externo e interno de la empresa multinacional. Específicamente, sugerimos que el sentir nacionalista acentúa las lógicas institucionales nacionales, genera categorizaciones basadas en estatus y las empresas locales, y alza el énfasis en las identidades organizacionales nacionales. Estas manifestaciones impactan las operaciones de las empresas multinacionales al limitar el espacio para hibridación de las prácticas las rutinas diferentes, aumentando el riesgo de discriminación por estereotipación por las audiencias locales, y afianza la resistencia a ideas y a prácticas extranjeras entre los miembros extranjeros. Sugerimos que las empresas multinacionales tengan tres opciones estratégicas al responder al sentir nacionalista: evitar las manifestaciones, mitigar sus implicaciones, o apalancar el sentir nacionalista como ventaja para la empresa multinacional. En resumen, nuestro marco da un punto de entrada para los académicos de Negocios Internacionales examinen las implicaciones estratégicas del sentir nacionalista de las empresas multinacionales.

Resumo

Acadêmicos em negócios internacionais têm reconhecido o impacto do nacionalismo político e econômico sobre empresas multinacionais (MNE). Complementamos essas abordagens destacando as manifestações sociológicas do nacionalismo e suas implicações para as MNE. Argumentamos que os sentimentos nacionalistas, ou seja, suposições amplamente compartilhadas de superioridade sobre outras nações e culturas, constituem um elemento pouco pesquisado, mas crítico, em negócios internacionais (IB). Com base em insights da sociologia organizacional, elucidamos como sentimentos nacionalistas se manifestam no ambiente externo e interno de MNE. Especificamente, sugerimos que sentimentos nacionalistas acentuam a lógica institucional nacional, geram categorização baseada em status de empresas estrangeiras e domésticas, e aumentam a ênfase em identidades organizacionais nacionais. Essas manifestações impactam as operações de MNE ao limitar o espaço para hibridização de práticas e rotinas distintas, aumentam o risco de discriminação e estereotipagem por parte de públicos locais, e enraizam a resistência a ideias e práticas estrangeiras entre membros da organização. Sugerimos que MNEs têm três escolhas estratégicas para responder a sentimentos nacionalistas: evitar suas manifestações, mitigar suas implicações ou alavancar sentimentos nacionalistas a favor da MNE. Em suma, nosso modelo fornece um ponto de partida para acadêmicos de IB examinarem as implicações estratégicas dos sentimentos nacionalistas para as MNE.

摘要

国际商务学者已经认识到政治和经济民族主义对跨国企业(MNE)的影响。我们通过强调民族主义的社会学表现及其对MNE的启示来补充这些方法。我们认为, 民族主义情绪, 即普遍认为优于其它国家和文化的假设, 构成了国际商务(IB)中研究不足但至关重要的元素。我们借鉴组织社会学的见解, 阐明了民族主义情绪如何在MNE外部和内部环境中体现。具体来说, 我们认为民族主义情绪强调国家制度逻辑, 对国内外企业进行基于地位的分类, 并高度强调国家组织认同。这些表现形式限制了不同行为及惯例的混合空间, 增加了来自当地受众的歧视和成见的风险, 并加深了组织成员对外国想法和做法的抵制, 从而影响了MNE的运营。我们建议MNE在应对民族主义情绪时采取三种战略选择: 避免其表现、减轻其影响或利用民族主义情绪为MNE带来优势。总之, 我们的框架为IB学者研究民族主义情绪对MNE的战略启示提供了一个起点。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past decade, scholars have become increasingly interested in the organizational and managerial implications of nationalism (e.g., Alvarez & Rangan, 2019). International business (IB) scholars have made important contributions by highlighting the resurgence of economic and political forms of nationalism, including heightened trade barriers, domestic subsidies, and government discrimination (Kim, & Siegel, 2024; Lubinski & Wadhwani, 2020; Tung, Zander, & Fang, 2023; Zhang & He, 2014). Drawing on international relations theory and political science, this stream of work has highlighted how nationalist state policies and geopolitical rivalries reshape the market conditions in which multinational enterprises (MNEs) function.

In many countries, the rise of political and economic nationalism has been accompanied by an increase in societal-level nationalist sentiments (Heath, Taylor, Brook, & Park, 1999), that is, wide-spread social attitudes and beliefs about superiority over other nations (Ariely, 2012). Nationalist sentiments constitute a sociological form of nationalism (Bonikowski, 2016) because they manifest in the language, behaviors, and beliefs of individual members of society. While political and economic nationalism typically impact the MNE through external regulatory institutions and political pressures, nationalist sentiments permeate the MNE’s organization through the everyday interactions of employees, managers, customers, and other stakeholders.

Accordingly, we develop a framework for understanding the implications of nationalist sentiments for the MNE. To do so, we build on insights from organizational sociology, which has long focused on the socio-cultural forces influencing organizational activities. Specifically, we draw on three distinct but inter-related literatures – institutional logics, status-category theories, and organizational identity – to theorize the implications of nationalist sentiments for the MNE. Based on the institutional logics literature, we suggest that nationalist sentiments accentuate national logics in both the home and host countries of MNEs, resulting in limits to hybridization of practices and knowledge sourced from different locations. Integrating work on organizational status and categorization, we argue that nationalist sentiments reinforce categorical status distinctions between foreign and domestic firms, leading to greater discrimination and stereotyping of foreign MNEs. Drawing from the organizational identity literature, we propose that nationalist sentiments increase emphasis on national organizational identity, which, we argue, increases resistance to foreign elements.

We discuss how each of these implications of nationalist sentiments impact the MNE’s unique ability to effectively manage operations in multiple country locations. Recognizing nationalist sentiments as a contextual factor, rather than a coercive institutional pressure, we also examine different ways in which MNEs may respond to nationalist sentiments, both at home and abroad. Specifically, we focus on how MNEs may avoid, mitigate, and leverage the manifestations and implications of nationalist sentiments.

By directing attention to nationalist sentiments, we complement and expand current works on nationalism that predominantly draw on international relations and political science. In particular, by building on mechanisms from organizational sociology, we develop a flexible framework that can be applied to the managerial and organizational aspects of the MNE. Finally, by conceptualizing the different potential responses available to MNEs, we hope to stimulate new research questions and further scholarship on the effects of nationalist sentiments on the MNE.

Nationalism and nationalist sentiments

Nationalism is not new to the study of the MNE and international business. Political and economic nationalism were important drivers of European trading companies in the 17th and 18th centuries (Lubinski & Wadhwani, 2020), as well as imperialist market expansions of the 19th century and early 20th centuries in Africa, Asia, and South America (e.g., Donzé & Kurosawa, 2013). Concerns about nationalist policies and their impact on foreign direct investment featured prominently in foundational research on the MNE in the 1960s and 1970s (e.g., Perlmutter, 1969). While the emphasis on nationalism faded during the era of liberalization and globalization that began in the late 1970s, recent developments have renewed interest in the topic.

Notably, one of the commonalities across both older and more recent works is that they focus almost exclusively on economic and political nationalism, which emanates from government policies and regulations. By contrast, our focus is on nationalist sentiments, i.e., widely shared beliefs and assumptions about shared national identities that manifest in daily actions, languages, and decisions (e.g., Hjerm & Schnabel, 2010). Such “everyday nationalism” (Bonikowski, 2016) matters: marketing scholars have highlighted how consumer nationalism lowers demand for foreign goods and services (Balabanis, Diamantopoulos, Mueller, & Melewar, 2001), while management research indicates that nationalist sentiments may deter collaborations with foreign partners (e.g., Ertug, Cuypers, Dow, & Edman, 2023). Nationalist sentiments are also relevant for internal organizational processes. Ayub and Jehn (2006) uncover how nationalist sentiments aggravate conflict in nationally diverse workgroups, while Köllen, Koch, and Hack (2020) find that organizations’ national identity, and its embedded nationalism, has an adverse effect on foreign employee retention.

Although these works provide arguments and evidence that nationalist sentiments matter for MNEs, their attention is directed at specific mechanisms and outcomes. Missing from the literature is a broader framework of nationalist sentiments and their implications that can be applied across different facets of the MNE. We contribute to addressing this lacuna by offering a theoretically grounded conceptualization of nationalist sentiments and their impact on the MNE.

Defining nationalist sentiments

We follow Kosterman and Feshbach’s (1989) widely used definition to conceptualize nationalist sentiments as “a perception of national superiority and an orientation toward national dominance [that] consistently implies downward comparisons of other nations.” While nationalist sentiments have been conceptualized in multiple ways by political scientists and sociologists, we suggest that Kosterman and Feshbach’s definition is particularly suitable for IB scholars, for several reasons.

First, by conceptualizing nationalist sentiments in terms of perceptions and assumptions, the definition follows a sociological approach to nationalism, which emphasizes how meanings and affective orientations shape nationalistic behaviors (Bonikowski, 2016, p. 428). As such, Kosterman and Feshbach’s definition allows us to clearly distinguish nationalist sentiments from the economic and political dimensions of nationalism that have been the focus of most work in IB. The emphasis on everyday nationalism in Kosterman and Feshbach’s definition also distinguishes nationalist sentiments from nation-building political movements and anti-colonialism. We do not suggest that nationalist sentiments should replace these economic and political perspectives; rather, we see nationalist sentiments as a complement to the economic and political approaches, all of which together make up the nationalism concept.

Second, Kosterman and Feshbach’s definition delineates both the specific attributes of nationalist sentiments and the nation as their common basis. It highlights how nationalist sentiments emphasize the distinction between members of a nation and non-member outsiders, as well as the sense of “superiority” and “dominance” over “other nations.” While distinctions between in- and outgroup members and feelings of superiority and dominance can arise from numerous factors (e.g., individual or organizational beliefs, cultural differences, etc.), Kosterman and Feshbach’s conceptualization explicitly designates the nation as the primary antecedent for such beliefs and attitudes. In doing so, it aligns with IB’s emphasis on the nation as a central unit of analysis.

Finally, by identifying the attributes of nationalist sentiments – and by articulating their specific antecedents in the nation state – Kosterman and Feshbach’s definition provides a means for IB scholars to investigate their theoretical and empirical implications for the MNE. As we discuss further below, the attributes of nationalist sentiments can be linked directly to existing work in IB. Moreover, the conceptualization of nationalist sentiments itself has been empirically validated (Ariely, 2012), using large, publicly available, multi-year data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). In sum, Kosterman and Feshbach’s definition offers a robust theoretical conceptualization of nationalist sentiments, with a readily available empirical application.

The manifestations and implications of nationalist sentiments

To consider the implications of nationalist sentiments, we draw on literature from the organizational sociology perspective (e.g., Greenwood, Meyer, Lawrence, & Oliver, 2017). Organizational sociology examines how meanings, identities, and social interactions shape managerial behaviors and strategies, both inside and outside the organization. As such, it is particularly well-suited for analyzing and theorizing the implications of nationalist sentiments, while at the same time complementing the emphasis on formal institutions, power, and policy that prevails in economic and political approaches to nationalism.

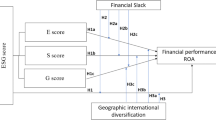

We discuss the manifestations and implications of nationalist sentiments through three perspectives in organizational sociology: institutional logics, status-categorization theories, and organizational identity. While these perspectives are anchored at different levels of analysis, they share an emphasis on narratives and meanings, cultural symbols, and normative beliefs and assumptions, all of which are central to nationalist sentiments. Using these three literatures as lenses, we suggest that nationalist sentiments result in accentuated national logics, status-categorization of foreign and national firms, and increased emphasis on national organizational identity. We argue that these manifestations generate three implications for the MNE: limits to hybridization, increased discrimination and stereotyping, and greater resistance to foreign elements.

The three perspectives from organizational sociology also offer insights into how MNEs may respond to nationalist sentiments, i.e., by avoiding exposure to the manifestations of nationalist sentiments, mitigating the implications of these manifestations, or attempting to leverage the manifestations and implications to their advantage. Figure 1 highlights the relationship between nationalist sentiments, its various manifestations, their implications, and the MNE’s potential responses. To re-emphasize a point made earlier, while this framework builds on a particular definition of nationalism, other perspectives on nationalism have been offered by scholars around the world, some of which might be more pertinent for different questions and concerns. We revisit this matter in our discussion section.

Accentuated national logics

A hallmark of the MNE is that it operates in highly complex settings that encompass multiple societal and national institutional logics (e.g., Newenham-Kahindi & Stevens, 2017). Institutional logics are “socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices […] by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences” (Thornton, Ocasio, & Lounsbury, 2012:2). Cultural symbols are themes that individuals use to interpret their surroundings and make decisions, while material practices constitute the behaviors and actions that embody and reproduce institutional logics. Institutional logics originate in various societal sectors – including the state, the family, the community, etc. – yet they typically overlap within the same organizational field, leading to high levels of complexity (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, 2011).

In the case of the MNE, we suggest that this institutional complexity is compounded by the presence of national logics (e.g., Luo, 2007). National logics are the collection of values, symbols, and societal characteristics that together form the basis for identifying what it means to be a member of a national polity. While national logics often incorporate elements from religious, state, or family logics, they are distinct in that they locate at the country level, as opposed to societal sectors. National logics thus constitute a form of meta-logic that provide an over-arching narrative and guide to authentic national identity (Frank, Meyer, & Miyahara, 1995). Although national logics emerge in the process of nation-building and are central to the modern nation state, they are not synonymous with nationalism; in many countries, the national logic is but one element of the complex institutional environment of the MNE, co-existing with – and often subservient to – other logics, including those of the market, the corporation, or the community. In such contexts, the national logic is typically vaguely defined, allowing actors to populate it with a wide variety of meanings, symbols, and values, depending on their own interests and interpretations.

The advent of nationalist sentiments, we suggest, changes both the nature of national logics and their position in the institutional environment. Since nationalist sentiments constitute common beliefs about shared national identities (e.g., Hjerm & Schnabel, 2010), their salience serves to crystallize and demarcate the particular symbols, meanings and values associated with the national logic. While elements of some sectoral logics (such as religion or community) may be encompassed underneath the now dominant national logic, elements from other logics (such as the market or the corporation) may be actively excluded from it. In effect, nationalist sentiments tighten (Gelfand, Nishii, & Raver, 2006) societal members’ understanding of what the core attributes of their national logic are, resulting in less room for actors to define the national logics according to their own interests and interpretations (Aguilera, Judge, & Terjesen, 2018).

Through the lens of nationalist sentiments, the cultural values and characteristics associated with the national logic come to be seen as the “foundation of the moral order of modern society” (Greenfeld, 2016:90), thus elevating their position within the complex multifaceted institutional environment. In doing so, nationalist sentiments also accentuate the “dominance” and “superiority” of the national logic over other logics that also exist in the institutional environment (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989). Specifically, the “downward comparison” that Kosterman and Feshbach (1989) identify as central to nationalist sentiments results in critical and disapproving appraisals of those values, symbols, and material practices that diverge from those of the national logic. Such alternatives become designated as “minority logics” (Durand & Jourdan, 2012), and organizations that embody them are seen as deviants from the prevailing logic.

Importantly, the accentuation of national logics does not eject minority logics from the field as such; rather, it serves to create a stratified hierarchy of logics, one in which other logics are subservient to and dominated by the national logic. As nationalist sentiments accentuate the national logic and elevate its position in the hierarchy, minority logics may become increasingly peripheral and fringe to the field. In this way, the accentuation of the national logic bifurcates the previously heterogeneous institutional field into a hierarchy dominated by the national logic.

Implications of accentuated national logics: Imposing limits on hybridization

In complex markets with multiple co-existing logics, organizations typically engage in hybridization, i.e., the combination of multiple practices and cultural values, drawn from different logics (e.g., Yoshikawa, Tsui-Auch, & McGuire, 2007). Hybridization provides not only a means to maintaining legitimacy vis-à-vis multiple stakeholders (Battilana & Dorado, 2010), but also a source of learning, innovation and the recombination of practices into new knowledge (Besharov & Smith, 2014). Hybridization is particularly critical for MNEs as it allows them to combine practices from the variegated logics they face due to their geographically dispersed presence. In doing so, hybridization not only ensures that MNEs can strike a balance between home and host-country practices, but also serves to enable the firm’s recombination of knowledge and capabilities.

Successful hybridization requires that the underlying logics themselves are flexible and pliable, and that the institutional environment tolerates heterogeneity, contestation, and non-conformity in organizational responses to multiple logics (Besharov & Smith, 2014). Nationalist sentiments undermine these requirements, both because the tightening of the national logic reduces flexibility, and because the distinct hierarchy of national and non-national logics limit room for contesting and combining different logics. In home countries, the primacy placed on national logics may force MNEs to tone down or abandon the adoption of elements from alternative logics, especially those that are seen as being foreign or associated with other national logics. For example, certain governance models may be viewed as incompatible with the values and norms of the national logic, making it difficult for MNEs to adopt these at home. Consequently, MNEs may find it difficult to transfer best practices that are linked to foreign logics from subsidiaries to headquarters. In host countries, MNE subsidiaries may struggle to reconcile practices and behaviors that are inherited from the home country with the local national logic. For example, Fortwengel and Jackson (2016) highlight how German-style apprenticeship practices failed to gain traction in the U.S. because such practices defied the local national logics’ emphasis on individualism and open labor markets.

Status-categorization of foreign firms

Nationalist sentiments may also manifest in how external stakeholders – including customers, suppliers, competitors, and allies – categorize and rank foreign and domestic firms. According to categorization theories, stakeholders classify organizations based on characteristics and attributes that signify value and meaning (Negro, Kocak, & Hsu, 2010). As such, categorization has implications for authenticity and distinctiveness. Status theory, in turn, indicates that stakeholders order field-level categories hierarchically, with ascending levels of worth (e.g., Sharkey, 2014). In this way, categories are used to make sense of and distinguish between different organizational groupings, particularly under conditions of uncertainty and ambiguity.

One of the defining aspects of the MNE is that it operates as a foreign entity in host-country environments. While stakeholders might categorize MNEs based on various organizational attributes – including their capabilities, country-of-origin, and past performance – we suggest that the MNE’s foreignness may become a more prominent and leading evaluation criterion when nationalist sentiments are prevalent. Nationalist sentiments entail a comparison between the in- and outgroup, i.e., between those who are members of the nation and those who are not (Ertug et al., 2023). In- and outgroup membership is not limited to individuals but also applies to organizations. As a result, the increased salience of ingroup and outgroup membership that is associated with nationalist sentiments may lead to greater distinction between foreign and national firms.

For example, stakeholders may become more likely to group foreign firms together in one category, and also clearly distinguish between the foreign and domestic category. Moreover, because firms are grouped based on whether they are foreign or not, heterogeneity within the category (i.e., among foreign firms) may become less salient for stakeholders. To be sure, audiences may distinguish some foreign firms due to historical home–host-country relationships or inter-country animosity (Arikan & Shenkar, 2013), yet for most foreign entrants, country-of-origin and organization-specific elements will be of secondary importance to their categorization as foreign entities.

Implications of status-categorization: Increased risk of discrimination and stereotyping

Categories exhibit varying ascriptions of worth and value (Sharkey, 2014), with some categories enjoying high status positions (Jensen, Kim, & Kim, 2011). Status positions are based not only on objective measures of value, but also on the level of adherence to criteria that are recognizable and meaningful to evaluators (e.g., Zuckerman, 1999). While a foreign categorization can be a boon to MNEs, particularly in segments with strong status-connotations (e.g., luxury, finance, or advanced technologies), in countries where nationalist sentiments are strong, membership in the national category is likely to function as a key determinant of status, with local MNEs enjoying the advantages of being seen as national champions and a source of national pride. Conversely, the “downward comparison” of foreigners that is integral to nationalist sentiments implies that, in these circumstances, foreign MNEs may be viewed as low-status entities (Kim, & Siegel, 2024).

Categorization as a low-status foreign firm may increase discrimination and stereotyping in various ways. Foreign MNEs may be excluded from local networks, industry associations, and professional organizations (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). Such “outsidership” and lack of embeddedness reduces a foreign MNE’s access to local knowledge and practices, limiting its interactions with host-country stakeholders. Discrimination may also increase consumer animosity (Amine, 2008) and make local partners less willing to engage in partnerships or collaborations (Ritvala, Granqvist, & Piekkari, 2021; Zhang & He, 2014). Additionally, the status distinction between foreign and local categories may make it difficult for foreign MNEs to adopt local practices, as they may be seen as inauthentic and penalized for trying to pass themselves off as domestic firms.

Importantly, because the “foreign” categorization places all non-domestic firms in the same grouping, discrimination and stereotypes are often applied to foreign firms in general, regardless of their firm-specific capabilities. While some firms may face discrimination due to their specific country-of-origin, these effects are in addition to the overall status-categorization of foreign firms. As a result, MNEs may face increased risk of illegitimacy-by-association (Jonsson, Greve, & Fujiwara-Greve, 2009), as the misbehavior or poor performance of one foreign firm is seen as indicative of that category at large. Consequently, MNEs face potential discrimination costs due not only to their own actions, but also those of other foreign firms.

National organizational identities

Nationalist sentiments also manifest at the firm level, specifically in the MNE’s national organizational identity. An organizational identity is the members’ collective understanding of those features of the firm that are central, distinctive, and adaptively enduring over time (Dennis A Gioia, Schultz, & Corley, 2000). Arising through the interaction of individual members’ assumptions, beliefs, values and personal identities, organizational identities are expressed through the use of “key values, labels, products, service or practices” that signal “who we are” as a firm (Gioia, Patvardhan, Hamilton, & Corley, 2013). In MNEs, organizational identities facilitate the coordination of complex knowledge flows across subunits, as well as the delegation of authority to subsidiaries. MNEs’ identities often originate in their home country, where local institutional environments have an imprinting effect on the organization’s initial practices, routines, and organizational structures (Christopher Marquis & Qiao, 2023). While the identity evolves as the MNE internationalizes (Fortwengel, 2021), the national identity component typically remains an integral part of who the organization is (Pant & Ramachandran, 2017).

Strong nationalist sentiments may have a particularly powerful imprinting effect on the MNEs’ national organizational identity. Nationalist sentiments embody assumptions of superiority (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989), and individual organizational members may express these assumptions and beliefs through their daily work (Bonikowski, 2016). Executives may incorporate nationalist language and phrases into internal documents and memoranda, and workspaces may be adorned with flags, emblems and paraphernalia linked to national identity. MNEs may also adopt policies that align more closely with their national identity, including language requirements, dress codes, or employee classification systems (Köllen et al., 2020). The daily interactions of individuals may also become imbued with symbols, phrasing, and values that reflect sentiments linked to national identity (e.g., Koveshnikov, Tienari, & Vaara, 2020). Collectively, these expressions heighten attention to, and emphasis on, the MNE’s national identity.

While the MNE’s national organizational identity may be most prominent at headquarters, it is also likely to permeate the identities of foreign subsidiaries. Subsidiary organizational identities typically represent a balance between the imprinting effect of headquarters and host-country environments (e.g., Pant & Ramachandran, 2017). This balance may tilt towards headquarters in MNEs with strong national organizational identities that are rooted in home country nationalist sentiments. Through the transfer of organizational practices, the deployment of home country expatriates, and selective hiring of like-minded “foreign” locals (e.g., Caprar, 2011), the values and belief systems of headquarters find their way into the organizational identity of subsidiaries.

Implications of national organizational identities: Resistance to foreign elements

As organizations that operate within and across multiple cultural and institutional contexts, MNEs are regularly exposed to foreign ideas, norms, and practices that diverge from their core organizational principles. The ability to learn from, adopt, and transfer these foreign novelties is a critical capability, one where the MNE’s organizational identity plays a crucial role (Kogut & Zander, 1996). We suggest that national organizational identities shaped by nationalist sentiments increase resistance to such foreign elements.

Because they define not only who the organization is but also who it is not, organizational identities often shape firms’ willingness to engage with novel ideas and technologies. Specifically, ideas, practices and technologies that are associated with the outgroup, i.e., that which the organization is not (Ashforth & Mael, 1989), are frequently discounted and viewed as illegitimate by organizational members. While such discounting happens in all firms, it may be particularly prevalent in MNEs with strong national organizational identities because, by definition, all foreign ideas and practices fall within the outgroup. Compared to other organizational identities, where the outgroup may be based on industry- or technology-specific identities, the sheer scope of the national organizational identity’s outgroup significantly narrows the range of acceptable practices, norms, and ideas.

Moreover, since nationalist sentiments entail a “downward comparison” of other countries and cultures, the opposition to foreign elements may be more potent in national organizational identities, as compared to other organizational identities. Rather than being ignored or discounted, foreign ideas, practices, routines, and norms may be actively opposed by members who view them as inferior or threatening to the central and distinctive features of the organizational identity. For example, labor representatives in German firms vehemently opposed the introduction of U.S.-style shareholder-oriented corporate governance practices on the grounds that these challenged traditional values of workplace cooperation (Fiss & Zajac, 2004).

We are not suggesting that all foreign elements are automatically ignored or resisted; rather, our argument is that in MNEs with strong national organizational identities, foreign ideas, practices, and other elements will, on average, find less fertile ground for adoption and dispersion throughout the MNE’s global network. MNE subsidiaries may, for example, curtail their exploration and learning in the host country, under the belief that foreign ideas are unsuitable to their core identity. Strong national organizational identities may also entail less transfer of new knowledge among the MNE’s subunits, in the belief that valuable knowledge should come from headquarters. Resistance to foreign elements may also have implications for MNEs’ willingness to hire foreign nationals or to promote cultural and national diversity within the organization. They may also impact human capital development, as knowledge of the home-country language and culture become central to promotion and career advancement (Hinds, Neeley, & Cramton, 2014).

MNE responses to nationalist sentiments

Taken together, the logics, status-categorization, and organizational identity literatures provide a lens by which to examine the implications of nationalist sentiments for MNEs across multiple levels. As these literatures highlight, the effects of nationalist sentiments lie not only in the bias of legal and regulatory institutions, or the political risks of expropriation and regulatory discrimination, but also in the shared meaning systems, cognitive categorizations, and personal and organizational identification. As we discuss below, however, the three theoretical lenses also offer insights into different ways by which MNEs might avoid, mitigate, and even leverage the manifestation and implications of nationalist sentiments. Table 1 offers an overview of these three response strategies in relation to the different manifestations and implications of nationalism. In the following we discuss each of these in greater detail.)

Avoiding the manifestations of nationalist sentiments

We first look at how MNEs can avoid nationalist sentiments, specifically by sidestepping their manifestations at different levels. Avoidance may be a particularly relevant response strategy when the impact of nationalist sentiments is either exogenous to the MNE (i.e., beyond the firm’s control and influence) or too costly to engage with directly. Effective avoidance strategies thus seek to position MNEs outside the boundaries within which nationalist sentiments manifest.

Avoiding accentuated national logics

As we have noted, nationalist sentiments may limit the MNE’s scope for hybridization by accentuating nationalist logics over alternative logics. Logic accentuation tends to be exogenous, especially in the host country, which suggests that – if the constraints on hybridization are a major concern – MNEs may do best to avoid these conditions altogether. The most obvious means to do so is to refrain from entering markets with strong nationalist sentiments or, alternatively, to divest from host countries where nationalist sentiments have made national logics increasingly salient. This response aligns with the classical view of national institutional environments as selection mechanisms that filter out deviant and non-isomorphic organizations.

An alternative approach, emphasized in the institutional logic perspective, is for MNEs to carve out minority spaces and niche geographies in countries with accentuated nationalist sentiments (Christopher Marquis & Lounsbury, 2007). Rather than exiting a market altogether, such strategies represent defections to alternative venues that offer room for greater multiplicity and diversity in underlying logics (Negro, Hannan, & Rao, 2011). Applied to the MNE, such an avoidance response may take the form of niche market entries that focus on sub-regions where nationalist sentiments are relatively weak. MNEs may, for example, limit their operations to global cities and cosmopolitan regions where national logics are less salient. Notably, such niche avoidance strategies are not necessarily limited to host countries, as MNEs may constrain their operations to cosmopolitan settings in the home country in order to avoid confrontations with home-country nationalist sentiments (Antia, Kim, & Pantzalis, 2013).

Avoiding status-categorizations based on foreignness

Status-based categorizations are constructed by specific audience groups, including customers, suppliers, competitors, and other stakeholders, who contrast and compare organizations operating in different categories (Hsu & Grodal, 2021). Consequently, MNEs seeking to avoid status-categorizations based on foreignness should focus on market segments and niches where audience evaluations are not informed by nationalist sentiments. For example, in host market sectors where domestic competitors are non-existent, local audiences will struggle to juxtapose foreign and non-foreign firms. Here, the MNE may be able to operate without facing a disadvantaging status-categorization based on their foreignness, even if nationalist sentiments are strong in the country overall.

Audiences also find it difficult to establish category-based status evaluations when organizations are boundary-spanners that simultaneously operate across multiple categories (Roberts, Simons, & Swaminathan, 2010). In such cases, firms can often continue operating without facing discrimination and sanctions (e.g., Vergne, 2012). Applied to the MNE, these insights suggest that status-categorizations based on foreignness can be avoided in markets where incumbent host-country competitors collaborate with foreign firms, as this might make it difficult for audiences to sharply distinguish between foreign and local entities.

Avoiding national organizational identities

MNEs’ national organizational identities are typically imprinted by the home country’s institutional environment (Christopher Marquis & Qiao, 2023). One option to avoid imprinting is for MNEs to move their headquarters to locations where nationalist sentiments are less pronounced. In an effort to sidestep nationalist sentiments in their home countries, several MNEs have shifted their headquarters to cities and regions with high levels of global trade but weaker nationalist sentiments. MNEs may also sidestep nationalist sentiments by reducing the role of headquarters or decoupling them from the rest of the MNE. Such strategies may be particularly effective for MNEs that follow a multi-domestic strategy, with considerable subsidiary autonomy. Decoupling may allow subsidiaries to function largely independent of the home-country imprinting effect at headquarters.

MNEs can also avoid the effects of host-country nationalist sentiments through selective hiring. Organizational identities are derived from the shared meanings and assumptions of members; hence researchers have highlighted how staffing and employment can influence the trajectory and shape of identification (Battilana & Dorado, 2010). By screening for nationalist sentiments and hiring employees whose values and meanings align with the firm, both at home and in subsidiaries, MNEs can minimize the imprinting effects of nationalist sentiments on their identities.

Mitigating the implications of nationalist sentiments

In contrast to avoidance, mitigation strategies engage directly with the implications of nationalist sentiments with the goal of reducing or offsetting their impact on the MNE. Consequently, mitigation is most effective when the implications of nationalist sentiments are within the MNE’s control and influence.

Mitigating the limits to hybridization

As noted previously, limits to hybridization have a negative impact on the MNE because they reduce its ability to transfer and recombine practices that stem from different institutional logics. To overcome these limitations, organizations can engage in structural compartmentalization (Besharov & Smith, 2014), whereby different logics are housed in distinct sub-units and functions of the organization, and knowledge transfer is managed by boundary spanners who can navigate multiple logics. In the case of the MNE’s foreign subunits, compartmentalization entails distinguishing between practices that adhere to the host-country national logic, and those that follow the logic of the home country. Compartmentalization may depend on dual-identity expatriates (Vora & Kostova, 2007), who can be boundary-spanners sharing knowledge between both logics.

The limits to hybridization may also be overcome by proactive efforts to integrate ideas from minority or foreign logics into the dominant national logic. Organization scholars have shown how novel and illegitimate ideas can be absorbed into prevailing logics through the use of discursive strategies. For example, Vaara and Tienari (2011) highlight how the proponents of an international merger among four Nordic banks deployed various cultural narratives to motivate the combination of practices and values originating in different national logics. By drawing on narratives, MNEs can thus mitigate the homogenizing effects of accentuated national logics, both at home and abroad.

Mitigating discrimination and stereotyping

Organizations can work to restrain discrimination and stereotyping by external audiences in several ways. Most directly, organizations can reduce the impact of negative evaluations by adopting norms and practices that signal conformity with field-level norms and practices. While such isomorphism strategies have long been a central focus in IB research, their effectiveness may be limited when the discrimination and stereotyping is based on the MNE’s foreign categorical membership or country-of-origin, as opposed to its discrete actions and behaviors.

A more proactive mitigation strategy calls for engaging directly with audiences to change their discriminatory stereotypes. MNEs can for example employ legitimation strategies to help valorize and de-stigmatize low-status categories. Newenham-Kahindi and Stevens (2017) show how foreign mining companies operating in Tanzania were able to overcome their liability of foreignness by working in tandem with local communities to establish common norms and shared goals. MNEs can also work proactively to shift the overall image of both foreign firms and specific countries. Notably, because nationalist sentiments lead to stereotyping of foreign firms as a group – as opposed to individual firms – mitigation strategies need to focus at the category level, i.e., to change local attitudes to foreign firms in general. Effective mitigation strategies may thus require coordination among foreign firms, as well as monitoring and controlling to ensure individual “rogue” foreign firms do not damage the status and image of the category as a whole.

Finally, MNEs can also mitigate discrimination and stereotyping by changing or obscuring their category membership (Delmestri & Greenwood, 2016). Such “category shifts” create uncertainty in audience evaluations, thereby reducing the potential for negative stereotyping and discrimination. For example, Pant and Ramachandran (2017) document how the Hindustan Unilever proactively managed its external image so as to avoid being categorized as a foreign entity during an eras of strong nationalist fervor in India.

Mitigating resistance to foreign elements

Extant research suggests that MNEs can mitigate internal resistance to foreign ideas, routines, practices and other elements by emphasizing a more dynamic understanding of the MNE’s national organizational identity (Gioia et al., 2013), one that explicitly incorporates change, flexibility, and novel ideas. Scholars increasingly recognize that organizational identities are malleable and evolutionary in nature, as opposed to rigid and unchanging (Gioia et al., 2000). Indeed, many organizational identities survive specifically because they effectively absorb new ideas and practices without abandoning that which is distinctive, central, and enduring.

To enable such flexibility, however, organizational leaders must work proactively to instill employees with a sense of confidence and security in their underlying identity (Arikan, Koparan, Arikan, & Shenkar, 2019). MNEs can, for example, ensure that members maintain a focus on the national organizational identity, while at the same time incorporating foreign employees, practices and mindsets from other national systems and cultures. As an illustration, Fortwengel (2021) documents how an internationalizing German automotive company managed to build a coherent MNE identity that encompassed significant cultural and organizational variety, while at the same time maintaining the critical elements of its original German identity. Alternatively, firms may designate some elements and labels as core to the MNE identity, while others as being transmutable. When entering foreign markets, for example, the Swedish furniture retailer IKEA allowed lower-level practices and peripheral organizational attributes to be adapted, while at the same time making sure to maintain its core philosophy and vision, which were closely linked to its Swedish identity (Jonsson & Foss, 2011).

Leveraging the implications of nationalist sentiments

Finally, MNEs may also be able to leverage nationalist sentiments for their own benefit, in both the home country and beyond. Leveraging can encompass a reactive component (i.e., positioning the firm to take advantage of opportunities that arise exogenously due to nationalist sentiments) as well as a more proactive component (wherein firms actively seek to accentuate and strengthen the manifestations and implications of nationalist sentiments).

Leveraging limits to hybridization

Limits to hybridization can serve as a competitive opportunity for MNEs in their home countries because they are especially disadvantageous for foreign entrants. To take full advantage of their firm-specific capabilities, foreign entrants typically adapt their products, practices, and strategies in some way to fit the host-country market. Such adaptation often takes place through processes of translation and bricolage, by which foreign firms create hybrid forms that combine elements of different logics. By placing limits on hybridization, accentuated national logics not only stymie this adaptation process; they also increase pressures for isomorphism on foreign firms. In addition to being costly in time and resources, isomorphism may limit the foreign entrants’ ability to leverage strategic organizational practices that are central to their competitive advantage. In this way, home-country MNEs can take advantage of the exogenous forces that arise due to nationalist sentiments by positioning themselves in product and resource markets where the limits to hybridization create the biggest disadvantage for foreign entrants.

MNEs may also seek to further accentuate national logics – and thus the limits on hybridization – by purposely emphasizing and playing up nationalist sentiments. This may be done by highlighting the superiority of organizational practices that align closely to the national logic (e.g., Mordhorst, 2014) or by purposely recalling historical events that are specific to the national logic (e.g., Sasaki, Kotlar, Ravasi, & Vaara, 2020). By reinforcing the cultural authenticity and uniqueness of the national logic, such measures further limit foreign entrants’ room for hybridization, thereby benefiting MNEs in their home country.

In some cases, the limits to hybridization can also be leveraged by MNEs operating in host country settings. Specifically, the alternative to isomorphism is for foreign firms to explicitly distance themselves from the national logic. As noted previously, the accentuation of a national logic does not imply that alternative logics are expunged from that country. Instead, the result is a hierarchy of logics, where alternatives to the national logic exist, but are deemed to be lower-ranked minority logics. Such minority logics are still legitimate and viable (Christopher Marquis & Lounsbury, 2007), yet they command less attention from field members. The limits to hybridization that arise from accentuated logics, combined with the inherent hierarchy of logics, imply that most home-country firms will refrain from employing practices that are associated with minority logics, even when doing so might be beneficial. This creates an opportunity for foreign firms to adopt practices that are primarily available to adherents of the minority logic (Edman, 2016).

For example, Siegel et al. (2019) show how foreign firms in South Korea were able to take advantage of a strong social norms related to gender and work. According to the authors, most South Korean firms operated along a national logic that defined managerial roles as inherently male-oriented positions, hence they largely refrained from hiring talented women. Rather than adopt these practices, foreign firms instead adhered to a minority logic, one that viewed managerial roles as non-gender specific. This gave foreign firms advantageous access to an underutilized and highly talented labor pool of women, which engendered real economic advantages for the foreign firms, as compared to their domestic competitors.

Leveraging discrimination and stereotypes

At home, MNEs can leverage their higher status positions to gain advantages in both the local labor market and among domestic consumers (Fischer, Zeugner-Roth, Katsikeas, & Pandelaere, 2022). Home-country MNEs can also benefit when uniform categorical stereotypes are applied to foreign firms, since such stereotypes blur firm-specific heterogeneity, making it difficult for individual foreign firms to stand out. More proactively, home-country MNEs can use foreign firms’ low status and associated stereotypes as an argument for excluding them from industry associations and critical knowledge networks. Home-country MNEs may also purposely categorize foreign competitors as one homogeneous (out-)group.

When operating in host countries, MNEs can leverage discrimination and stereotypes about foreign firms to carve out niches away from the dominant market segments. Rather than trying to compete with local firms in the established market (where their foreignness becomes a disadvantage), foreign entrants can use local stereotypes as an excuse to enter under-served markets or alternative segments. Edman (2016), for example, shows how stereotypes that applied to foreign firms in the Japanese banking market provided them with a “license to deviate” from prevailing norms to introduce a new disruptive lending format that challenged the status-quo. In this way, being categorized as foreign may often shield the MNE subsidiary from institutional pressures and local audience expectations. As above, the foreign MNE can further accentuate these exogenous benefits by actively encouraging and contributing to the distinction between foreign and non-foreign firms.

Leveraging resistance to foreign elements

Organizational resistance to foreign elements can also offer opportunities for MNEs, in various ways. For example, subsidiaries that exhibit a strong resistance to foreign elements may be more reliant on home-country headquarters as a source of knowledge and new practices; as a result, headquarters may enjoy greater control over these individual units. Resistance to foreign elements may also increase the efficiency of knowledge transfers, as MNE subunits with strong resistance to foreign elements may be more willing and motivated to adopt and implement strategic practices that emanate from MNE headquarters in the home country.

Resistance to foreign ideas and practices can also translate into greater loyalty and commitment to the organization’s own routines and structures, thereby increasing productivity and loyalty. By resisting the introduction of foreign elements, employees may strengthen the organizational identity itself, making the firm less sensitive to both short-term fads and disruptive external threats that challenge its central, distinctive, and enduring attributes. This may be particularly important during times of uncertainty and upheaval, as it provides a common template for employees to reference (Vaara & Tienari, 2011).

Discussion

Our study urges IB scholars to add a sociological lens to the prevailing emphasis on the political and economic forms of nationalism. A sociological perspective recognizes nationalism as a societal-level phenomenon, embodied in the shared assumptions and beliefs of the national populace. While political and economic forms of nationalism typically manifest in the rhetoric of politicians, or discriminatory government policies, a societal-level approach focuses on nationalist sentiments, i.e., nationalism expressed in the everyday attitudes and behaviors of individuals, including employees, managers, customers, partners, and suppliers. Therefore, nationalist sentiments have the potential to permeate and impact the operating environments both within and outside the MNE. Management scholars increasingly recognize how shared societal norms, values, and cultural narratives shape the structure of both individual organizations and broader markets. We argue that nationalist sentiments play an equally important role in shaping the organization and strategy of MNEs.

Broadening the conceptualization of nationalism to include nationalist sentiments opens new avenues of research. Firstly, it raises the question of how societal-level nationalisms interact with political and economic manifestations. While the different nationalisms often move in parallel, they are distinct in terms of the levels of analysis (e.g., societal vs. governmental), manifestations (actions and behaviors vs. policies and rhetoric), and implications (social exclusion and illegitimacy vs. legal and political discrimination). Accordingly, an important topic of future research is to compare the effects of different nationalism types on aspects of the MNE. Scholars can also examine whether and how the effects of sociological, political, and economic nationalism vary across different functions of the MNE (e.g., corporate governance, HR, market entry, etc.), as well as across different institutional settings (e.g., emerging markets vs. developed markets).

The dynamics of MNEs and nationalist sentiments

MNEs can act as carriers of nationalist beliefs and assumptions, both in the home and host country. This might be particularly true for MNEs who favor leveraging responses that accentuate and further nationalist sentiments. This raises questions about how MNE activity might shape nationalist sentiments. For example, do acquisitions of host-country firms by foreign MNEs spur nationalist sentiments (even if such activities might have little impact on economic and political expressions of nationalism)? In the home country, does offshoring by domestic firms increase nationalist sentiments? Anecdotal evidence suggests MNEs can trigger nationalist sentiments, as exemplified by how foreign MNEs’ decisions to stop sourcing cotton from China’s Xinjiang providence provoked a backlash from Chinese consumers. An emphasis on nationalist sentiments provides future work with a theoretical framework to investigate these interactions in greater detail.

Future research can also focus on the interaction between the different implications of nationalist sentiments, and MNE responses to these. While we have distinguished between logics, categorizations, and organizational identities for the sake of conceptual clarity and parsimony, these three factors are typically intertwined and mutually reinforcing. Consequently, an important avenue for future research is to examine when and how accentuated national logics drive categorization effects and an impetus of national organizational identity, as well as how these two manifestations serve to further accentuate logic hierarchies. In a similar fashion, future work can also examine how MNEs may combine different responses across the different implications; MNEs may, for example, seek to avoid accentuated national logics while simultaneously leveraging status-based categorization effects and mitigating resistance to foreign ideas and practices.

Conceptualizations of nationalism

Even though we have discussed the suitability of the nationalism definition we use, and noted its acceptability within social sciences, it is not exempt of qualifiers. In particular, this definition has been developed by two Western scholars. It will come as no surprise, given the importance of the phenomenon, that scholars from around the world have offered their own perspectives on nationalism (as a necessarily miniscule and arbitrary selection to illustrate the variety of approaches, see e.g., Chatterjee, 1986; Mboya, 1986; Shin, 2006; Yoshino, 2019; Zhou, 2006). Whether with respect to their motivation, emphasis, and scope, these other perspectives on nationalism differ both from the conceptualization we use and from each other. It is also worth noting that perspectives that have ties to a particular region of the world also differ among themselves, so there is no ethnic or natural essentialism implied. Indeed, as expected for a topic such as nationalism, historical, geographical, political, and intellectual contingencies, as well as the individual background and social milieu of the scholars, all play a role in the emergence and articulation of a given perspective on nationalism. Future research can leverage this diversity in nationalism conceptualizations by invoking, refining, or combining one or more of these perspectives to better understand phenomena that relate to MNEs, as well as topics of concern to IB and international management more generally. In total, our field is bound to benefit from such inquiries that harness the richness of perspectives that exist around the world.

Operationalizing nationalist sentiments

A critical question is how to measure nationalist sentiments. Data collection and methodologies that are designed to provide proxies for societal attitudes, values and perceptions are commonly used in IB research, generally relying on large-scale surveys of respondents across countries. Although rarely used in management research (but see Ertug et al., 2023 for a recent example), large-scale survey data on nationalist sentiments are available and have been used in sociology and political science.

A commonly used dataset for this purpose is the National Identity Module in the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), a collaborative research effort covering over 50 countries. The National Identity module is available in several waves, allowing for both cross-country and temporal analysis. The two items in this module that are commonly used to create a scale that capture nationalist sentiments are: “The world would be a better place if people from other countries were more like the [country nationality]” and “Generally speaking, [country] is a better country than most other countries.” These items capture respondents’ perceptions and assumptions of the ingroup (i.e., their country) versus the outgroup (i.e., foreigners) and to what extent they look downward on them, which aligns with our conceptualization of nationalist sentiments.

Scholars interested in the implications of individual employees’ or managers’ nationalist sentiments can also rely on experimental approaches to prime nationalist sentiments in experimental settings. Alternatively, scholars may use natural language processing models (NLPs) to gauge nationalist sentiments in text sources such as annual reports, media coverage and online commentary (Yiu, Wan, Chen, & Tian, 2022).

Practical implications: Recognizing and responding to nationalist sentiments

Our framework also offers practical insights for managers. Work on identity hybridization (e.g., Pache & Santos, 2012) and productive tensions around competing logics (Smets, Jarzabkowski, Burke, & Spee, 2014), for example, shows how organizations might overcome limits to hybridization by effectively balancing and recombining dominant and minority logics in host countries. Similarly, research on category-spanning (Hsu, Hannan, & Kocak, 2009) and status mobility (Delmestri & Greenwood, 2016) provide guidance for overcoming discrimination and stereotyping, and work on imprinting and identity transformation (D.A. Gioia et al., 2013) will be helpful for MNE managers seeking to build organizational identities that attenuate nationalists identities and resistance to foreign ideas.

Conclusion

While international management scholars have predominantly focused on the implications of economic and political nationalism, we argue that a sociological approach adds a critical dimension to our understanding of how nationalism impacts the MNEs. By highlighting various ways in which nationalist sentiments manifest, both at home and abroad, the implications of nationalist sentiments for the MNE, as well as possible response strategies, we add a new dimension to nationalism in international business, for both scholars and practitioners.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Judge, W. Q., & Terjesen, S. A. (2018). Corporate governance deviance. Academy of Management Review, 43(1), 87–109.

Alvarez, S., & Rangan, S. (2019). Editors’ comments: The rise of nationalism (Redux) – An opportunity for reflection and research. Academy of Management Review, 44(4), 719–723.

Amine, L. S. (2008). Country-of-origin, animosity and consumer response: Marketing implications of anti-Americanism and Francophobia. International Business Review, 17(4), 402–422.

Antia, M., Kim, I., & Pantzalis, C. (2013). Political geography and corporate political strategy. Journal of Corporate Finance, 22, 361–374.

Ariely, G. (2012). Globalization, immigration and national identity: How the level of globalization affects the relations between nationalism, constructive patriotism and attitudes toward immigrants? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(4), 539–557.

Arikan, I., Koparan, I., Arikan, A. M., & Shenkar, O. (2019). Dynamic capabilities and internationalization of authentic firms: Role of heritage assets, administrative heritage, and signature processes. Journal of International Business Studies, 1–35.

Arikan, I., & Shenkar, O. (2013). National animosity and cross-border alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1516–1544.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Ayub, N., & Jehn, K. A. (2006). National diversity and conflict in multinational workgroups: The moderating effect of nationalism. International Journal of Conflict Management, 17(3), 181–202.

Balabanis, G., Diamantopoulos, A., Mueller, R. D., & Melewar, T. C. (2001). The impact of nationalism, patriotism and internationalism on consumer ethnocentric tendencies. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1), 157–175.

Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

Besharov, M. L., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: Explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 364–381.

Bonikowski, B. (2016). Nationalism in settled times. Annual Review of Sociology, 42(1), 427–449.

Caprar, D. V. (2011). Foreign locals: A cautionary tale on the culture of MNC local employees. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 608–628.

Chatterjee, P. (1986). Nationalist thought and the colonial world: A derivative discourse: Zed Books.

Delmestri, G., & Greenwood, R. (2016). How Cinderella became a queen theorizing radical status change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(4), 507–550.

Donzé, P.-Y., & Kurosawa, T. (2013). Nestlé coping with Japanese nationalism: Political risk and the strategy of a foreign multinational enterprise in Japan, 1913–45. Business History, 55(8), 1318–1338.

Durand, R., & Jourdan, J. (2012). Jules or Jim: Alternative conformity to minority logics. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1295–1315.

Edman, J. (2016). Cultivating foreignness: How organizations maintain and leverage minority identities. Journal of Management Studies, 53(1), 55–88.

Ertug, G., Cuypers, I. R., Dow, D., & Edman, J. (2023). The effect of nationalism on governance choices in cross-border collaborations. Journal of Management.

Fischer, P. M., Zeugner-Roth, K. P., Katsikeas, C. S., & Pandelaere, M. (2022). Pride and prejudice: Unraveling and mitigating domestic country bias. Journal of International Business Studies, 53(3), 405–433.

Fiss, P., & Zajac, E. J. (2004). The diffusion of ideas over contested terrain: The (non)adoption of a shareholder value orientation among German firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 501–534.

Fortwengel, J. (2021). The formation of an MNE identity over the course of internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 1-27.

Fortwengel, J., & Jackson, G. (2016). Legitimizing the apprenticeship practice in a distant environment: Institutional entrepreneurship through inter-organizational networks. Journal of World Business, 51(6), 895–909.

Frank, D. J., Meyer, J. W., & Miyahara, D. (1995). The individualist polity and the prevalence of professionalized psychology: A cross-national study. American Sociological Review, 360-377.

Gelfand, M. J., Nishii, L. H., & Raver, J. L. (2006). On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1225.

Gioia, D. A., Patvardhan, S. D., Hamilton, A. L., & Corley, K. G. (2013). Organizational identity formation and change. Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 123–193.

Gioia, D. A., Schultz, M., & Corley, K. G. (2000). Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 63–81.

Greenfeld, L. (2016). Advanced introduction to nationalism: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Greenwood, R., Meyer, R. E., Lawrence, T. B., & Oliver, C. (2017). The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism: Sage.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371.

Heath, A., Taylor, B., Brook, L., & Park, A. (1999). British national sentiment. British Journal of Political Science, 155-175.

Hinds, P. J., Neeley, T. B., & Cramton, C. D. (2014). Language as a lightning rod: Power contests, emotion regulation, and subgroup dynamics in global teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(5), 536–561.

Hjerm, M., & Schnabel, A. (2010). Mobilizing nationalist sentiments: Which factors affect nationalist sentiments in Europe? Social Science Research, 39(4), 527–539.

Hsu, G., & Grodal, S. (2021). The double-edged sword of oppositional category positioning: A study of the US E-cigarette category, 2007–2017. Administrative Science Quarterly, 66(1), 86–132.

Hsu, G., Hannan, M. T., & Kocak, O. (2009). Multiple category memberships in markets: An integrative theory and two empirical tests. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 150–169.

Jensen, M., Kim, B. K., & Kim, H. (2011). The importance of status in markets: A market identity perspective. Status in Management and Organizations, 87-117.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411–1431.

Jonsson, A., & Foss, N. J. (2011). International expansion through flexible replication: Learning from the internationalization experience of IKEA. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(9), 1079–1102.

Jonsson, S., Greve, H., & Fujiwara-Greve, T. (2009). Undeserved loss: The spread of legitimacy loss to innocent organizations in response to reported corporate deviance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54, 195–229.

Kim, J. H., & Siegel, J. I. (2024). Paying for legitimacy: Autocracy, nonmarket strategy, and the liability of foreignness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 69(1), 131–171.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? Coordination, identity, and learning. Organization Science, 7, 502–518.

Köllen, T., Koch, A., & Hack, A. (2020). Nationalism at work: Introducing the “Nationality-Based Organizational Climate Inventory” and assessing its impact on the turnover intention of foreign employees. Management International Review, 60(1), 97–122.

Kosterman, R., & Feshbach, S. (1989). Toward a measure of patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. Political Psychology, 10(2), 257–274.

Koveshnikov, A., Tienari, J., & Vaara, E. (2020). National identity in and around multinational corporations. In A. D. Brown (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Identities in Organizations (pp. 602–607). Oxford University Press.

Lubinski, C., & Wadhwani, R. D. (2020). Geopolitical jockeying: Economic nationalism and multinational strategy in historical perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 41(3), 400–421.

Luo, X. (2007). Continuous learning: the influence of national institutional logics on training attitudes. Organization Science, 18(2), 280–296.

Marquis, C., & Lounsbury, M. (2007). Vive la resistance: Competing logics and the consolidation of U.S. Community Banking. Academy of management journal, 50, 799.

Marquis, C., & Qiao, K. (2023). History Matters for Organizations: An Integrative Framework for Understanding Influences from the Past. Academy of Management Review, Advance online publication: https://journals.aom.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2022.0238.

Mboya, T. (1986). Freedom and after: East African Publishers.

Mordhorst, M. (2014). Arla and Danish national identity – business history as cultural history. Business History, 56(1), 116–133.

Negro, G., Kocak, Ö., & Hsu, G. (2010). Research on Categories in the Sociology of Organizations. In G. Hsu, G. Negro, & Ö. Kocak (Eds.), Categories in Markets: Origin and Evolution (Vol. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, pp. 3-35).

Negro, G., Hannan, M. T., & Rao, H. (2011). Category reinterpretation and defection: Modernism and tradition in Italian winemaking. Organization Science, 22(6), 1449–1463.

Newenham-Kahindi, A., & Stevens, C. E. (2017). An institutional logics approach to liability of foreignness: The case of mining MNEs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of International Business Studies, 49, 881–901.

Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2012). Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to conflicting institutional logics. Academy of Management Journal, Amj., 2011, 0405.

Pant, A., & Ramachandran, J. (2017). Navigating identity duality in multinational subsidiaries: A paradox lens on identity claims at Hindustan Unilever 1959–2015. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(6), 664–692.

Perlmutter, H. V. (1969). The tortuous evolution of the multinational corporation. Columbia Journal of World Business, 4(1), 9–18.

Ritvala, T., Granqvist, N., & Piekkari, R. (2021). A processual view of organizational stigmatization in foreign market entry: The failure of Guggenheim Helsinki. Journal of International Business Studies, 52, 282–305.

Roberts, P. W., Simons, T., & Swaminathan, A. (2010). Crossing Categorical Boundaries: The Implications of Switching from Non-Kosher Wine Production in the Israeli Wine Market. In G. Hsu, G. Negro, & Ö. Kocak (Eds.), Categories in Markets: Origin and Evolution (Vol. 31).

Sasaki, I., Kotlar, J., Ravasi, D., & Vaara, E. (2020). Dealing with revered past: Historical identity statements and strategic change in Japanese family firms. Strategic Management Journal, 41(3), 590–623.

Sharkey, A. J. (2014). Categories and organizational status: The role of industry status in the response to organizational deviance. American Journal of Sociology, 119(5), 1380–1433.

Shin, G.-W. (2006). Ethnic nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, politics, and legacy: Stanford University Press.

Siegel, J., Pyun, L., & Cheon, B. Y. (2019). Multinational firms, labor market discrimination, and the capture of outsider’s advantage by exploiting the social divide. Administrative Science Quarterly, 64(2), 370–397.

Smets, M., Jarzabkowski, P., Burke, G., & Spee, P. (2014). Reinsurance trading in Lloyd’s of London: Balancing conflicting-yet-complementary logics in practice. Academy of Management Journal, 58(3), 932–970.

Thornton, P., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process. London: Oxford University Press.

Tung, R. L., Zander, I., & Fang, T. (2023). The Tech Cold War, the multipolarization of the world economy, and IB research. International Business Review, 32(6), 102–195.