Abstract

We contend that the Uppsala internationalisation process (IP) Model offers the basis, yet unrealised, for a process theory of growth of the internationalising firm. From the Model’s origins, particularly in Penrosean theory, we develop this potential by offering a theory extension that explicates the organisational changes within the firm required to sustain international growth. This repositioning distinguishes us from previous attempts to amend, supplant or extend the IP Model. In developing the theory extension, we specify how we remain faithful to the IP Model’s behavioural assumption ground. We provide a model of the internationalising firm that posits non-linear growth paths. This is due to the challenges of synchronising the external opportunity seeking of the firm as it expands internationally with the internal capacity building required to realise these opportunities. Introducing to the IB field this asynchronicity problem, an absence of temporal concurrence, we show its potential in explaining organisational changes and discontinuities in the internationalising firm’s development as it seeks to grow. By extending the IP Model to offer a theory of growth of the internationalising firm, we provide the basis for further process scholarship on this topic that addresses contemporary concerns and developments.

Plain language summary

In recent years, the Uppsala Internationalisation Process Model (IP Model) has been a key framework for understanding how firms expand globally. However, there is a gap in the Model's ability to explain the internal changes a firm must undergo to capitalize on opportunities in foreign markets. This study aims to bridge that gap by proposing a theory that integrates internal drivers of growth with the external opportunities highlighted by the IP Model. This study suggests that firms must align their internal managerial and technological capacities with their external market opportunities to sustain growth. The researchers argue that these internal and external processes often do not progress at the same pace, leading to asynchronicities (lack of synchronisation) that can hinder a firm's momentum. The research builds upon the IP Model's focus on experiential learning and market commitments by adding the concept of internal capacity building. This approach is important because it acknowledges that a firm's growth is not just about seizing external opportunities but also about developing internal strengths. The type of study is theoretical, proposing an extension to an existing model rather than reporting on new empirical data. The results of this theoretical study highlight the importance of synchronizing a firm's internal development with its external market activities. The key finding is that growth depends on the firm's ability not only to identify and pursue market opportunities but also to develop its internal capacities to exploit these opportunities effectively. The researchers conclude that addressing the asynchronicities between internal capacity building and external opportunity seeking is crucial for the sustained growth of internationalising firms. The potential impact of this research is significant for businesses looking to expand internationally. It suggests that firms should pay close attention to their internal processes and capabilities while pursuing international opportunities. Future implications of this work could lead to more nuanced strategies for international growth, taking into account the complex interplay between a firm's internal dynamics and its external environment. This study advances our understanding of international business growth and provides a more comprehensive framework for firms to navigate the challenges of global expansion.

Résumé

Nous estimons que le modèle Uppsala du processus d'internationalisation (Internationalisation Process—IP) offre la base, non encore réalisée, d'une théorie du processus de croissance de l'entreprise s'internationalisant. À partir des origines du Modèle, en particulier de la théorie de Penrose, nous développons ce potentiel en proposant une extension théorique expliquant les changements organisationnels au sein de l'entreprise nécessaires pour soutenir la croissance internationale. Ce repositionnement nous distingue des tentatives antérieures de modification, de remplacement ou d'extension du modèle IP. En développant cette extension théorique, nous spécifions comment nous restons fidèles au fondement de postulats comportementaux du modèle IP. Nous apportons un modèle d'entreprise en voie d'internationalisation lequel postule des trajectoires de croissance non linéaires. Cela s'explique par les défis de synchroniser la recherche d'opportunités externes par l'entreprise lors de son expansion internationale avec la construction des capacités internes nécessaire pour concrétiser ces opportunités. Introduisant dans le domaine des affaires internationales ce problème d'asynchronisme, une absence de concurrence temporelle, nous mettons en lumière son potentiel pour expliquer les discontinuités et les changements organisationnels dans le développement de l'entreprise en voie d'internationalisation, et ce lorsqu’elle cherche à croitre. En élargissant le modèle IP pour proposer une théorie de la croissance de l'entreprise en voie d'internationalisation, nous jetons les bases d'une recherche plus approfondie sur ce sujet, laquelle répond aux préoccupations et aux développements contemporains.

Resumen

Sostenemos que el modelo del proceso de internacionalización (IP por sus iniciales en inglés) de Uppsala ofrece la base, aún sin explotar, para una teoría del proceso de crecimiento de la empresa en proceso de internacionalización. A partir de los orígenes del modelo, en particular en la teoría de Penrose, desarrollamos este potencial ofreciendo una ampliación de la teoría que explica los cambios organizacionales dentro de la empresa necesarios para sostener el crecimiento internacional. Este reposicionamiento nos distingue de anteriores intentos de modificar, suplantar o ampliar el Modelo del Proceso de Internacionalización. Al desarrollar la ampliación de la teoría, especificamos cómo nos mantenemos fieles a los supuestos de comportamiento del Modelo del Proceso de Internacionalización. Proporcionamos un modelo de empresa en proceso de internacionalización que plantea trayectorias de crecimiento no lineales. Esto se debe a los retos que plantea sincronizar la búsqueda de oportunidades externas por parte de la empresa a medida que se expande internacionalmente con el desarrollo de las capacidades internas necesarias para materializar estas oportunidades. Al introducir al campo de Negocios Internacionales este problema de asincronía, una ausencia de concurrencia temporal, mostramos su potencial para explicar los cambios organizacionales y las discontinuidades en el desarrollo de la empresa que se internacionaliza a medida que busca crecer. Al ampliar el Modelo del Proceso de Internacionalización para ofrecer una teoría del crecimiento de la empresa en proceso de internacionalización, sentamos las bases para una mayor investigación sobre este tema que aborde las preocupaciones y los desarrollos contemporáneos.

Resumo

Afirmamos que o modelo do processo de internacionalização (IP) de Uppsala oferece a base, ainda não concretizada, para uma teoria do processo de crescimento da empresa que se internacionaliza. Desde as origens do Modelo, particularmente na teoria de Penrose, desenvolvemos este potencial pelo oferecimento de uma extensão da teoria que explica as mudanças intraorganizacionais necessárias para sustentar o crescimento internacional. Este reposicionamento distingue-nos das tentativas anteriores de alterar, suplantar ou ampliar o Modelo IP. Ao desenvolver a extensão da teoria, especificamos como permanecemos fiéis aos pressupostos comportamentais do Modelo IP. Fornecemos um modelo de empresa que se internacionaliza que postula caminhos de crescimento não lineares. Isto se deve aos desafios de sincronizar a busca de oportunidades externas da empresa à medida que ela se expande internacionalmente com a capacitação interna necessária para concretizar essas oportunidades. Apresentando ao âmbito de IB este problema de assincronicidade, uma ausência de concorrência temporal, mostramos o seu potencial na explicação de mudanças organizacionais e descontinuidades no desenvolvimento da empresa que se internacionaliza à medida que esta procura crescer. Ao estender o Modelo IP para oferecer uma teoria de crescimento da empresa que se internacionaliza, fornecemos a base para estudos adicionais sobre este tópico que abordam preocupações e desenvolvimentos contemporâneos.

摘要

我们认为, 乌普萨拉国际化过程 (IP) 模型为国际化公司成长的过程理论提供了基础, 但尚未实现。从模型的起源, 特别是在彭罗斯理论中, 我们通过提供理论扩展来开发这种潜力, 该理论扩展详细解释了维持国际成长所需的公司内部的组织变革。这一重新定位使我们有别于之前修改、取代或扩展IP模型的尝试。在理论扩展的开发中, 我们具体说明了我们如何仍然忠实于IP模型的行为假设基础。我们提供了一个设定了非线性成长路径的国际化公司的模型。这是由于公司在国际扩展过程中寻求外部机会与实现这些机会所需的内部能力建设同步所面临的挑战。通过向国际商务 (IB) 领域引入这种异步性问题 (即时间上缺乏并发性) , 我们展示了其在解释国际化公司在寻求成长过程中的组织变革和不连续性方面的潜力。通过扩展IP模型以提供国际化公司的成长理论, 我们为解决当代问题和发展的这一主题的进一步学术研究提供了基础。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, there has been a renewed debate on the Uppsala Internationalisation Process (IP) Model (Forsgren & Holm, 2021; Håkanson, 2021; Treviño & Doh, 2021). This attention is justified as the IP Model in its various versions remains among the most influential theoretical achievements in the international business (IB) field. Nonetheless, aspects of the model remain under-explored. Despite characterisation of the internationalisation of the firm “as a growth process” (Forsgren & Johanson, 1992: 11), we contend that the IP Model has not realised its potential as a theory of the growth dynamics of the internationalising firm. Our aim in this paper is to suggest a way forward to do so.

Not developed in the various Uppsala versions are the internal change processes in the firm that are required to exploit opportunities in international markets. Accordingly, we offer a process extension of the IP Model by incorporating internal drivers of growth (capacity building) that interact with the external drivers (opportunity seeking) that have remained the focus of the IP Model. Firms need to synchronise their internal managerial and technological capacity building with the decision to exploit the foreign market opportunities they perceive. However, the interdependence of these processes presents a growth dilemma: they are unlikely to proceed at the same pace, producing asychronicities that jeopardise forward momentum.

A theory of growth of the internationalising firm

The IP Model has, from its earliest formulation, been an explanation of dynamism in the firm through an iterative cycle of knowledge and commitment: experiential learning gained through acting in foreign markets reduces decision-makers’ risk perceptions and alerts them to the possibilities of further market opportunities. In specifying these conditions for international expansion, the IP Model represents the embryonics of a theory of growth. In this section, we fulfil this potential by proposing a theory extension. As is appropriate for a theory extension, we retain the growth mechanism that has remained at the core of the multiple versions of the IP Model: the external opportunity seeking of the firm that leads to tangible commitments in foreign markets. To this ‘outside–in’ mechanism we add an ‘inside–out’ growth mechanism: the internal capacity building required to realise these opportunities. This is consistent with the assumption ground of the original theory, reflecting Penrosean insights on the internal dynamics in the firm that are triggered when the firm grows.Footnote 1 Our extension can be described as theory adaptation (Jaakkola, 2020) with an ‘envisioning’ goal: that is, “to reconfigure, shift perspectives, or change” (MacInnis, 2011:138) how the IP Model is seen by the IB field. We commence with the assumption ground for our theory, situating it firmly in the behavioural tradition to which the IP Model also belongs.

Behavioural assumption ground

We develop our theory extension consistent with the intellectual traditions of the original IP Model, thus avoiding inappropriate theory blending in the form of theoretical additions that are incommensurate with the original (Okhuysen & Bonardi, 2011). Based on a behavioural theory of the firm, the original IP Model can be positioned in what was then the nascent field of organisation theory. This makes its assumption ground – with regards to the nature of the firm, the market, managerial decision-making and of theory itself – a decisive paradigmatic break with the neo-classical economics of the time (Vahlne & Johanson, 2014). We now explain how we adhere to these same assumptions, and highlight how, in doing so, we also align with a Penrosean view on the growth of the firm, a decisive influence on the IP Model that has been acknowledged, but not fully explored.

In relation to the first assumption – about the firm – we follow the IP Model in conceiving the firm as a “decision-making system” (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977: 26). This system is based on a behavioural process of managerial problem solving that relies on the accumulation of knowledge acquired through learning by doing. Decision-makers in the firm manage risk such that the firm does not exceed its level of ‘tolerable risk’ when making foreign market commitments. This conceptualisation aligns with Penrose’s view of the firm, which is that of an “administrative framework” (1959:149) for the productive utilisation of its resources.

The second assumption relates to the firm’s decision-making environment: the market. We follow the 2009 IP Model by augmenting a behavioural view of the firm with a behavioural view of markets. Accordingly, markets are networks of business relationships in which the firm invests (Richardson, 1972). This makes markets, that until then were “unknowable” in the Penrosean tradition, knowable (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009: 1426). Learning is about discovering the capabilities and potential (and limitations) of partners, as well as benefiting from their existing knowledge, and commitment is made to specific external partners. Business relationships assist in managing risk at a tolerable level as they generate trust and stability in exchanges. The firm’s opportunity horizon is broadened by the knowledge of its business relationship partners.

The third behavioural assumption concerns the nature of managerial decision-making. While we develop a firm-level theory – as did the IP Model before us – this necessarily rests on assumptions about how individuals make and follow through on organisational commitments. We follow the subjectivist view found in Penrose (1959) that also left its mark on the IP Model. In deciding on productive uses for its resources, “the firm strives to make a profit” (Penrose, 1959: 184), dependent on the judgements of its managers. That is, decision-making in the firm is based on the subjective ‘image’ that individual managers hold about the opportunities and risks that they face. Knowledge and experience shape this image. As Johanson and Vahlne (1977: 29) emphasise by saying that “the current state of internationalisation affects perceived opportunities and risks”, the firm’s current activities shape the possibilities that its decision-makers perceive for the productive use of its resources. In the 2009 version of the IP Model, Johanson and Vahlne (2009: 1424) assert knowledge of opportunities as “the most important element of the body of knowledge that drives the process”. Managerial capacities cannot, however, remove uncertainty, which is “unavoidable” and “irreducible” (Penrose, 1959: 62).

Fourth, consistent with the Penrosean tradition that emphasises the need for a process approach, we explain the course of events over time (Cornelissen, Höllerer, & Seidl, 2021). Penrose’s (1959) aim was to explain the “direction of the expansion” of the firm; that is, the how and why of a firm’s growth pattern, a history-dependent process based on the “cumulative growth of collective knowledge” (Penrose, 2009: 237). Process theories are explanatory rather than predictive, offering conceptual insights into how outcomes are produced. This makes their explanation historicist in nature (Stinchcombe, 1968). The IP Model take this historicist form, and explicitly so in its latest iterations (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). By positing a recurring knowledge–commitment cycle, Johanson and Vahlne (1977) offer a recursive process theory (Cloutier & Langley, 2020). That is, cycles of change produce a cumulative effect over time until the mechanism driving it is interrupted in some way. Growth is far from a pre-determined outcome.

The extended IP model

Consistent with a process approach, we now specify the change mechanisms for our theory extension. We commence with the growth mechanism that has been integral to the IP Model even in its original form: the opportunity development made possible by experiential learning.

The external (outside-in) growth mechanism

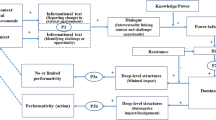

The firm positions itself in a foreign market by making commitments to other firms. If invested in over time, its position in this network of business relationships can potentially be an asset, and the basis for growth (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). In Fig. 1, our stylised representation of the internationalisation process as it unfolds over time, the firm’s external growth mechanism takes the form of developing opportunities through network positioning. The opportunity set consists of those opportunities that decision-makers perceive; that is, it is based on their subjective understanding of the possibilities available to them. As it actively positions itself as a network insider, an expansion of its opportunity set (t1 → t2, t2 → t5) and reduction in perceived risk due to the development of trust-based relationships, provides the firm with the potential basis for undertaking additional commitments in foreign markets. The firm will seek to adjust/extend its enterprise through further commitments that exist in its opportunity set such that its assessment of the risk in the new situation best approximates the risk that it is prepared to tolerate.

We propose that firms grow internationally by learning about opportunities in the process of committing to network partners, thereby retaining the core knowledge-commitment postulate of the IP Model. However, we contend that, as an explanation for firm growth, this is incomplete. Unlike Penrose’s theory, the IP Model in its various forms does not consider how change takes place within the firm as it grows. As Holm, Johanson and Forsgren (2015: 11) identified, the IP Model, “besides some specific assumptions about what the firm is or is not …, does not deal explicitly with processes inside the firm”. This is a considerable omission that we now address. The decision to commit to growth initiates, and in turn depends on, change processes within the firm. As a process that unfolds over time, growth is produced “by a creative and dynamic interaction between a firm’s resources and its market opportunities” (Penrose, 1960: 1). This leads us to propose a second mechanism that is necessary in driving growth: internal capacity building in the firm.

Internal (inside-out) growth mechanism

The knowledge–commitment cycle of the IP Model constitutes an ‘engine’ of growth driven by actions in the market, but, at the same time, growth is also driven by internal dynamics of the firm. Accumulating experiential knowledge is not just confined to learning about the opportunities in the markets in which the firm is active. Decision-makers also learn more about the additional uses and recombinations of the resources available to the firm, including how these resources can be augmented with those of its network partners. This is an endogenous driver of growth (Kor, Mahoney, & Michael, 2007; Tan, Su, Mahoney, & Kor, 2020) that makes growth path-dependent: the direction of the firm’s next expansion will be determined by its current technological capacities, its technological base. We represent this process of organisational change in Fig. 1. We now elaborate on the elements of this process.

Technological capacities and resource learning Penrose (1959) argued that firms that grow over an extended period of time invest in their technological capacities to provide a competitive positioning. Staff in the firm search for better uses of its resources, making its technology base inherently dynamic. Growth is driven by this process of discovering new possibilities for the firm’s existing technology base. We extend this Penrosean view to the technological bases of the firm’s business network partners that can also be leveraged to provide inter-organisational resource combinations. Finding new uses for the firm’s resources occurs through learning-by-doing and experimentation, including the formation of new external partnerships and resource links with other firms. As the experience of the firm’s decision-makers grows, so do the possibilities they identify for the resources available to the firm. While the resources of a firm are always limited, the potential applications of them need not be.

Identifying new productive uses for the firm’s resources is an act of innovation applying entrepreneurial intent. In seeking better (more productive) uses for the firm’s resources, decision-makers are not simply responding to increased demand, or satisficing. In a competitive environment, they are actively deliberating (Margolis, 1958) on where these better uses are to be found. This requires in-depth knowledge of the firm’s technological base, and of the resources that can be accessed from network partners. Such knowledge cannot simply be acquired from an external source because it is idiosyncratic to the firm. Experiential learning therefore does not only consist of learning about market opportunities, it is also about resource learning (Steen & Liesch, 2007). That is, experience enables learning about how the applications of the firm’s resources can be extended, including how it might be combined with the resources of external partners. In Fig. 1, resource learning takes place in the period between t1 and t3, enabling changes in the firm’s technological capacities by t4.

Entrepreneurial capacities and subjective opportunity perceptions Identifying and pursuing new productive uses for the firm’s resources require more than just the application of technical expertise and experience. Managerial acuity is essential for the firm to grow, and constitutes a component of the firm’s resources. Managerial capacity of the firm is of two kinds. The first is entrepreneurial in nature. Growth requires decision-makers with the capabilities to identify new productive possibilities for the firm’s resources, and to decide which are the most promising. For example, should the firm make further commitments to existing markets, or should it explore the opportunities that its network has opened up in a new market? Are managers able to match up market opportunities with the innovations that the firm has added to its technology base? This is depicted in Fig. 1: market opportunities exist in the network in which the firm positions itself, but these need to be perceived as such by decision-makers in the firm (t1 → t2, t4 → t5) as a precondition for an international commitment decision (t3, t6).

Coordination capacities and administrative reorganisation Managerial coordination consists of providing the administrative organisation needed for the efficient functioning of the firm. This is a skill set distinct from that of entrepreneurship, but is an equally important component of the managerial capacities required by a growing firm. It is because its activities and business functions need to be coordinated (Spender, 1994) that the firm is more than a bundle of resources. Coordination tasks include deciding on the administrative structure of the firm, maintaining operations while also planning and executing expansion, budgeting and making investment decisions, and accommodating the risks and acclimatising to the uncertainties involved. As the firm grows, the administrative organisation of the firm needs to be upgraded, placing higher demands on the firm’s managerial capacities. In Fig. 1, we incorporate the administrative reorganisation within the firm, showing it taking place in the period between t1 and t3. The firm is able to adjust its managerial capacities to the demands of growth by t4.

Coordination problems of growth are not avoided if the firm decides to grow by acquisition, or by inter-firm cooperation. The problems of post-merger integration are well known (Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy, & Vaara, 2017). The potential for acquisitions to create value for the acquiring firm is by no means assured. Coordination also needs to take place between firms, if inter-firm resource combinations are utilised to exploit market opportunities (Richardson, 1972). Inter-firm cooperation is demanding on both sides: it requires adapting plans, providing assistance and know-how, transferring while still protecting intellectual property, undertaking joint activities, building trust and managing interdependencies (Freytag, Gadde, & Harrison, 2017; Håkansson & Snehota, 1995). The pressures of growth can potentially be ameliorated through inter-firm cooperation, but not avoided.

In sum, growth relies on the mutual reinforcement over time of managerial (entrepreneurial and coordination) capacities on the one hand, and on the other hand, the material technology base that is available. This constitutes internal capacity building, and it enables the firm to identify and exploit the most productive uses of its resources, in the process potentially building an “impregnable” base from which to “adapt and extend its operations in an uncertain, changing, and competitive world” (Penrose, 1959: 137). Having such a renewable technological base, and with managers deliberating on opportunities for growing long run profits, cannot imply stasis in the firm. In fact, on the contrary, the firm will continue to find new uses for its technological specialisation in its state of “becoming” (Langley, Smallman, Tsoukas, & Van de Ven 2013:5) due to innovations by competitors and changing external conditions. Decision-makers in the firm know that it is risky to accept the status quo, as the risk of firm failure that could result from inaction is not inconsequential. In its management of risk, the firm has latitude to extend its risk frontier if the risk it is taking on is that of profitable opportunities, aligned with its organisational goals. As such, there is ‘good’ risk and there is ‘bad’, or uncompensated, risk (Kaplan & Mikes, 2012).

In our extended model, experiential learning remains a driver of the growth of the internationalising firm. Increased knowledge in the firm about new uses for its resources enables it to consider initiating a decision process on furthered commitment. Following the behavioural paradigm, our firm is continually searching in the ‘neighbourhood’ (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977) of its network for solutions to problems and for opportunities. However, managing expansion at the same time as managing the ongoing operations of the firm places demands on the firm’s management, with constraints on the managerial capacity in the firm likely to impose a limit on its potential for growth. In fact, Penrose (1959) famously nominates managerial capacity as the principal constraint on growth.

Managerial capacity is an even more acute problem in the geographically dispersed multinational, given the increased complexity of coordinating and orchestrating operations across geographical and institutional distances (Sun, Doh, Rajwani, & Siegel, 2021). Hence, the accumulation of experiential knowledge is insufficient as an explanation for firm growth: the firm also needs to develop the organisational capacity – structures, resources and people – to exploit this learning in order to grow. This produces the problem of asynchronicity: the temporal disjuncture between the firm’s internal capacity building and its external opportunity seeking.

Synchronisation

We propose that growth depends on the firm not just being able to accumulate market (that is, network) knowledge and to identify market opportunities through its current activities but it also needs to be developing its internal capacities to deliver on capturing these opportunities (Johanson & Johanson, 2021). If these do not align, growth may stall, or not occur at all. We consider that internal capacity building is likely to lag the identification of market opportunities, making this asynchronicity fundamental to the growth process. It takes time to commit to a decision and then to harness the necessary capacities to act on the decision. This time lag is represented in Fig. 1: an enlarged opportunity set is perceived in t2, but the organisational capacity for growth is only developed in t4, so the firm does not proceed to make a commitment decision in t3. Only in t6 do the perception of an opportunity and the availability of internal capacities coalesce to lead to a commitment decision to expand the firm’s foreign market activities.

Hence, our model posits that there needs to be a conjunction of conditions to occur in order for growth to eventuate: the firm needs to enlarge its opportunity set through network positioning and perceive the opportunity by exercising entrepreneurial capacities, as well as continuing its internal resource learning and further develop its coordination capacities, all of which take time. Were the firm to commit to expanding in t3, without these conditions being present, it would jeopardise its growth prospects: expansion abroad would be taking place without the firm having developed the internal capacity to support it. In short, the commitment to grow would be made prematurely.

We identify this as an asynchronicity problem, an absence of temporal concurrence, that emerges when multiple processes unfold in parallel but at differential rates, leading to a misalignment between them (Blagoev & Schreyögg, 2019). Because of asynchronicities, it is difficult to harmonise internal capacities with external opportunities when they arise so that the firm can act upon the opportunities. Even if the firm is able to act on the opportunity, before it is potentially lost to competitors, it may lack the internal capacity to exploit it effectively. Synchronisation problems in the firm provide an endogenous reason as to why growth in the firm is unstable and discontinuous, rather than a linear process over time.

We suggest three reasons for asynchronicities: investment delays (affecting resource learning), perceptual gaps (affecting the recognition of opportunities) and managerial limits (affecting coordination). The first reason is attributable to delays in making investments in the firm’s technology base and thereby realising the benefits of resource learning. Improving the organisational capacity and technological base of the firm requires championing a case in the firm for the change, investing in training, appointing new staff, building new production capacity and processes and cooperating with network partners to generate new resource combinations. These are the delays, risks and costs associated with innovation: introducing productive uses of resources that are new to the firm is more challenging than continuing to use them for the same applications. Recognising and reaching a consensus that the investment is needed, obtaining the approval and financing to make it happen, doing so at an appropriate scale, and reaching the point where the investment starts to provide a return are all time-consuming processes.

A second source of misalignment is a growing perceptual gap between those persons in the firm who are operating in the foreign market compared to those who are making the strategic decisions in the firm. The subjective opportunity sets of the two groups are likely to diverge at crucial points in time. Those managing foreign market operations will be the ones alert to potential opportunities, and developing new uses for the firm’s resources with other firms in their business network. However, transferring this experiential knowledge to other parts of the organisation – including to headquarters – is, as IB research informs us (Kogut & Zander, 1993), often problematic. Knowledge gained from personal experience is not readily transmissible, as it needs to be formalised into ‘objective’ knowledge that can be learned (Penrose, 1959: 53). That which managers in foreign markets perceive as promising opportunities may struggle to receive organisational support, in that headquarters is unlikely to always share the same subjective view of an opportunity set. Intra-firm conflict, assumed away in Penrose’s theory (Pitelis, 2007), is a likely consequence of these divergent subjective perceptions of market opportunities.

The third reason for asynchronicity stems from the greater coordination demands that are placed on the firm in periods of growth. We emphasise Penrose’s argument, in that managerial capacity, the ability of the management team to oversee and coordinate expansion, is crucial to growth, yet is among the scarcest of resources available to the firm. The current management team becomes stretched during a growth phase and, although this can be rectified through external hires, even if the need for additional talent has been recognised and new hires have been secured, it takes time to integrate them into the management team (Kor et al., 2007). Expanding the management team can require administrative reorganisations that disrupt existing routines and information flows.

As a result of these asynchronicities, the experiential knowledge that is gained may be dissipated or under-exploited by the firm, leading to a time lag between perceiving and acting on the opportunity (or recognising the problem) on the one hand, and, on the other hand, harnessing the internal capacities needed to capitalise upon that opportunity (or to resolve the problem). Growth in one time period can therefore produce the conditions for setbacks in the next. This may lead to organisational cycles in which periods of greater convergence between growth activities and internal capacities give way to rising tensions and divergence (Dooley & Van de Ven, 2017). This has been borne out in the experience of small firms, when rapid rates of international growth can lead to considerable strain on the firm’s ability to deliver for its customers (Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2003).

An exceptionally detailed illustration of asynchronicity can be found in Eriksson (2016:188), who observed in his case research on Atlas Copco’s expansion in China that “over time, more people got involved [in decision processes], managers had to start seeking commitments from other actors, and divergences and tensions increased ... Neither the subsidiary, nor the divisional HQ, nor any other actor …, could pursue the opportunity alone”. Threats to temporal concurrence of crucial events and activities, aggravated by more people in multiple locations becoming involved, resulted in foregone opportunities and managerial tensions.

Summary: asynchronicities as a dilemma of growth

While the IP Model, even in its most recent iteration, “assumes that commitments (resource allocation decisions) are made when there is a “reasonably positive” tradeoff between expected benefits and downside outcomes” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017: 1093), the Penrosean view that we adopt problematises this risk–benefit calculation. Penrose (1959) envisaged that organisational change for growth extends beyond decisions about resource allocation to include enhancements to the firm’s managerial (administrative and entrepreneurial) capacities. Growth requires entrepreneurship and innovation: applying experiential knowledge to combine resources in new ways and to broaden decision-makers’ subjective views of opportunities in the market. That is, the growth in the firm requires both managerially-intentioned, risk-managed opportunity seeking and internal capacity building.

Consistent with a process perspective and its axiom of there being no stasis, we recognise both enabling forces, such as those the IP Model has proposed, and inertial forces (Dow, Liesch, & Welch, 2018) which have potential to stymie change in the firm. This conceptualisation is consistent with that of Penrose’s (1959) administrative organisation. That is to say, internationalisation prospects in the firm’s opportunity set motivate decisions in the firm requiring change, but come up against resource and managerial capacity limitations that constrain development in the firm. The tensions, and their possible resolution, due to the asynchronicities of the two organisational processes is the change mechanism: the motor (Van de Ven & Poole, 1995) that transitions our firm to making new resource commitments, along the lines of Langley et al.'s (2013:5) firms which are “continually in a state of becoming”. The firm cannot remain unchanged in dynamic and uncertain contexts as decision-makers respond to situations of opportunity and of threats as they arise.

By explicitly incorporating these growth tensions into our model, we avoid making it deterministic. While growing the firm can be an organisational goal – a decision is taken to grow the firm – this does not imply growth is a necessary outcome. The operational dilemmas produced by the internationalisation process are recognised by Johanson and Vahlne (1977:26) in that “changes in the firm and the environment expose new problems [our emphasis] and opportunities”. We too acknowledge problems as a possible cause of no-growth or even ‘negative’ growth. In our model, we specify the nature of these problems and argue that they are constitutive of the growth process itself. Having introduced our theory extension, we now address its contemporary relevance.

Contemporary relevance

While there has been some debate about the ongoing relevance of the IP Model (in its various forms), we argue that this tradition of behavioural process theorising is valuable in understanding internationalisation in the current era dominated by digitalisation and global value chains, an era characterised by discontinuities and the reconfiguration of networks. We offer three domains of contemporaneity of our theory extension in this section.

First, digitalisation has introduced new manifestations of the ways in which international business is done (Nambisan, Zahra, & Luo, 2019). The establishment chain observed empirically by Uppsala researchers in the 1960s and 1970s continues to be transformed. In this modern digital context, there is a productive research agenda for exploring the asynchronicity problem. Has digitalisation increased the timeliness of firm responses to changing international market behaviours, and the speed at which opportunities are perceived and problems identified? Even assuming this is the case, it does not follow that the firm’s internal capacity adjustments to market signals are revolutionised with digitalisation, such that asynchronicity problems are moderated. Digitalisation may well make it easier for firms to detect and access opportunities, but this facility does not necessarily extend to internal capacity building. In fact, the velocity of external market dynamics may exacerbate the temporal gap between the emergence of market opportunities and the development of internal capacities.

Similarly, the rise and preponderance of global value chains entails coordination and orchestration challenges, and not just opportunities for growth. While global value chains provide expansion opportunities for insiders within these cross-border networks, asynchronicity problems may be exacerbated. We anticipate identification of both problems and opportunities to be challenging when production is organised in global value chains with their complex and opaque governance structures and knowledge asymmetries, as “searches in the area of the problem” (Cyert & March, 1963 in Johanson & Vahlne, 1977: 26) will be subject to informational difficulties, if not impossibilities. In this context of worldwide hyper-competition, we echo Buckley’s (2018:344) comment that “the international firm is the general case and the national firm is a special case”. There is opportunity to undertake comparative studies between internationalising firms fully adopting these new technologies and those lagging.

Second, we have demonstrated the IP Model’s ongoing theoretical merit. More can be done to develop our extension; in particular, to investigate asynchronicities empirically, and, further, to propose other – and perhaps competing – theoretical conclusions about the interdependencies between the firm’s internal developments and its opportunity seeking. We signal the potential for developing a organisational theory of change in the firm, consistent with our theorisation, and also applying it to the firm that chooses not to internationalise. We agree with Håkanson and Kappen (2017:1105), who recognise that the fundamentals of the IP Model have application beyond internationalisation to cover broader “strategic decision-making in firms”. We advocate further exploration of asynchronicities in these contexts, consistent with the IP Model’s intellectual heritage in Penrosean theory.

Finally, the IP Model remains the most prominent example of process theorising in the IB field where this theorising style remains an exception. The challenge for the field is to build on this heritage, and to explore other possibilities for process theorising. Unlike other research agendas that have been proposed, which are phenomenon-based (e.g. Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017), we advocate that a productive research agenda for the field is one that extends our theorising capacities (Cornelissen, 2017; Cornelissen et al., 2021). Understanding how firms change over time has always been a central question for the IB field, but has become more acute given the turbulence of the global business environment.

Limitations and future development

We accept that extending the IP Model as a process theory of growth could be perceived to have limitations, in that internationalising firms need not always aspire to grow. Our theory does not apply to all firms, and nor are we suggesting firms that aspire to grow will succeed. As we have defined it, growth in the firm can be an aspiration and, if this aspiration is not met with commensurate performance, a response will be initiated in the firm, and the decision will be taken to reduce its offshore commitments. In the event that performance falls short of aspirations, long-run profit expectations will not be met, risks in the existing situation will be assessed and related to those risks the firm is prepared to tolerate (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), and commitments will be adjusted. Repositioning, and possible withdrawal, are plausible as the firm searches in the neighbourhood of its declining performance for solutions, as Johanson and Vahlne (1977, 2009) envisaged. Negative growth and decline are accommodated in our theorising. Given the asynchronicities that are inherent to growth, the variations in internationalisation paths observed, and repeatedly reported as empirical evidence to reject the IP Model, are not necessarily exceptional.

We also acknowledge that growth can also be a consequence of the firm’s pursuit of other organisational goals, such as committing to customers who are dispersed internationally and require local representation (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989). We acknowledge that firm growth can also be a function of the growth of the industry in which it is positioned. However, our model focuses on firm-level mechanisms for growth, and does not incorporate these industry-level drivers. Our extension of the IP Model is, like the original, explanatory rather than predictive. We identify the mechanisms by which international growth occurs, and these mechanisms are amenable to empirical investigation. By proposing these mechanisms, it meets the test of an explanatory theory (Cornelissen, 2017) in that it “delves into underlying processes so as to understand the systematic reasons for a particular occurrence or non-occurrence” (Sutton & Staw, 1995:378).

Conclusion

We extend the IP Model to realise its potential as a process theory of growth of the internationalising firm, a shift in perspective for the field. We conceptualise this process as one that confronts the asynchronicities that develop between the internationalising firm’s external opportunity seeking on the one hand and its internal capacity building on the other. This process extension strengthens the IP Model’s origins as an incipient, albeit underdeveloped, theory of organisational change processes that has application beyond internationalisation. The process heritage that the Uppsala IP Model represents was pioneering and, with recent developments in process scholarship, potential remains for it to be explored in its own terms.

Notes

It is worth clarifying our use of terminology. Although our theory extension is firmly grounded in the Penrosean tradition, we have modified some of the terminology so that it is more in line with contemporary usage and with existing research on firm internationalisation. In particular, we settled on the term ‘internal capacity building’ to acknowledge our debt to the concept of ‘organisational capacity’ in Welch and Luostarinen (1988).

References

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Blagoev, B., & Schreyögg, G. (2019). Why do extreme work hours persist? Temporal uncoupling as a new way of seeing. Academy of Management Journal, 62(6), 1818–1847.

Buckley, P. J. (2018). How theory can inform strategic management education and learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 17(3), 339–358.

Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. (2017). Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48, 1045–1064.

Chetty, S., & Campbell-Hunt, C. (2003). Explosive international growth and problems of success amongst small to medium-sized firms. International Small Business Journal, 21(1), 5–27.

Cloutier, C., & Langley, A. (2020). What makes a process theoretical contribution? Organization Theory, 1(1), 1–32.

Cornelissen, J. (2017). Editor’s comments: Developing propositions, a process model, or a typology? Addressing the challenges of writing theory without a boilerplate. Academy of Management Review, 42(1), 1–9.

Cornelissen, J., Höllerer, M. A., & Seidl, D. (2021). What theory is and can be: Forms of theorizing in organizational scholarship. Organization Theory, 2, 1–19.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Dooley, K., & Van de Ven, A. (2017). Cycles of divergence and convergence: Underlying processes of organizational change and innovation. In A. Langley & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), The Sage handbook of process organization studies (pp. 593–600). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dow, D., Liesch, P. W., & Welch, L. S. (2018). Inertia and managerial intentionality: Extending the Uppsala model. Management International Review, 58(3), 465–493.

Eriksson, M. (2016). The complex internationalization process unfolded: The case of Atlas Copco’s entry into the Chinese mid-market. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Business Studies, Uppsala University.

Forsgren, M., & Holm, U. (2021). Complementing the Uppsala model? A commentary on Treviño and Doh’s paper “Internationalization of the firm: A discourse-based view.” Journal of International Business Studies, 52, 1407–1416.

Forsgren, M., & Johanson, J. (1992). Managing networks in International Business. London: Routledge.

Freytag, P. V., Gadde, L.-E., & Harrison, D. (2017). Interdependencies: Blessings and curses. In H. Håkansson & I. Snehota (Eds.), No business is an island: Making sense of the interactive business world (pp. 235–252). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Graebner, M. E., Heimeriks, K. H., Huy, Q. N., & Vaara, E. (2017). The process of postmerger integration: A review and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 1–32.

Håkanson, L. (2021). The death of the Uppsala School: Towards a discourse-based paradigm. Journal of International Business Studies, 52, 1417–1424.

Håkanson, L., & Kappen, P. (2017). The ‘Casino Model’ of internationalization: An alternative Uppsala paradigm. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9), 1103–1113.

Håkansson, H., & Snehota, I. (1995). Developing relationships in business networks. London: Routledge.

Holm, U., Johanson, J., & Forsgren, M. (Eds.). (2015). The Uppsala school of international business. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review: Academy of Marketing Science, 10(1), 18–26.

Johanson, J., & Johanson, M. (2021). Speed and synchronization in foreign market network entry: A note on the revisited Uppsala model. Journal of International Business Studies, 52, 1628–1645.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitment. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2006). Commitment and opportunity development in the internationalization process: A note on the Uppsala internationalization process model. Management International Review, 46(2), 165–178.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411–1431.

Kaplan, R. S., & Mikes, A. (2012). Managing risks: A new framework. Harvard Business Review, 90(6), 48–60.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1993). Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinational corporation. Journal of International Business Studies, 24, 625–645.

Kor, Y. Y., Mahoney, J. T., & Michael, S. C. (2007). Resources, capabilities and entrepreneurial perceptions. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7), 1187–1212.

Langley, A. N. N., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 1–13.

MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75, 136–154.

Margolis, J. (1958). The analysis of the firm: Rationalism, conventionalism, and behaviorism. Journal of Business, 31, 187–199.

Nambisan, S., Zahra, S. A., & Luo, Y. (2019). Global platforms and ecosystems: Implications for international business theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1464–1486.

Okhuysen, G., & Bonardi, J.-P. (2011). Editors’ comments: The challenges of building theory by combining lenses. Academy of Management Review, 36, 6–11.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Penrose, E. T. (1960). The growth of the firm—A case study: The Hercules Powder Company. Business History Review, 34(1), 1–23.

Penrose, E. (2009). The theory of the growth of the firm (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pitelis, C. N. (2007). Behavioral resource-based view of the firm. Organization Science, 18(3), 478–490.

Richardson, G. (1972). The organisation of industry. The Economic Journal, 82, 883–896.

Spender, J. C. (1994). Organizational knowledge, collective practice and Penrose rents. International Business Review, 3(4), 353–367.

Steen, J. T., & Liesch, P. W. (2007). A note on Penrosean growth, resource bundles and the Uppsala model of internationalisation. Management International Review, 47(2), 193–206.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1968). Constructing social theories. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sun, P., Doh, J. P., Rajwani, T., & Siegel, D. (2021). Navigating cross-border institutional complexity: A review and assessment of multinational nonmarket strategy research. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(9), 1818–1853.

Sutton, R., & Staw, B. (1995). What theory is not. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(3), 371–384.

Tan, D., Su, W., Mahoney, J. T., & Kor, Y. (2020). A review of research on the growth of multinational enterprises: A Penrosean lens. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(4), 498–537.

Treviño, L. J., & Doh, J. P. (2021). Internationalization of the firm: A discourse-based view. Journal of International Business Studies, 52, 1375–1393.

Vahlne, J.-E., & Johanson, J. (2014). Replacing traditional economics with behavioral assumptions in constructing the Uppsala Model: Toward a theory on the evolution of the Multinational Business Enterprise (MBE). In J. J. Boddewyn (Ed.), Research in global strategic management, 16, (Multidisciplinary Insights from New AIB Fellows) (pp. 159–176). Emerald.

Vahlne, J.-E., & Johanson, J. (2017). From internationalization to evolution: The Uppsala model at 40 years. Journal of International Business Studies, 48, 1087–1102.

Van de Ven, A., & Poole, M. (1995). Explaining development and change in organizations. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 510–540.

Welch, L. S., & Luostarinen, R. (1988). Internationalization: Evolution of a concept. Journal of General Management, 14(2), 34–55.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from feedback at an Uppsala Seminars in International Business presentation in November 2020 and a staff seminar at The University of Queensland in February 2021. We are grateful to Gabriel Benito and Ulf Holm for their extensive and constructive feedback on an earlier version of this paper, and Liena Kano for her editorial guidance. We dedicate this paper to the memory of Lawrence Welch. We hope we have written a paper he would have enjoyed reading, possibly one that he would have written himself.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Liena Kano, Guest Editor, 16 January 2024. This article has been with the authors for three revisions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liesch, P.W., Welch, C. Asynchronicities of growth: a process extension to the Uppsala model of internationalisation. J Int Bus Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-024-00702-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-024-00702-w