Abstract

Multinational enterprises (MNEs) and civil society (CS) interact in many ways across countries, with significant implications for these actors and for broader society. We review 166 studies of MNE–CS interactions in international business, general management, business and society, political science, sociology, and specialized non-profit journals over three decades. We synthesize this large and fragmented literature to characterize the nature (cooperation or conflict) and context (geography, industry, and issue) of MNE–CS interactions and uncover their antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Our review reveals important blind spots in our understanding of the antecedents and outcomes of MNE–CS interactions and uncovers substantial discrepancy between the contexts of real-world MNE–CS interactions and the contexts examined in the literature. We propose actionable recommendations to (i) better indicate and expand the contexts where MNE–CS interactions are studied; (ii) enrich understanding of the antecedents of MNE–CS interactions by leveraging institutional and cultural perspectives; (iii) reorient research on the outcomes of MNE–CS interactions by examining the temporal dynamics of MNE learning and legitimacy, and (iv) emphasize societal relevance as reflected, for example, in green capabilities and moral markets. We hope this review will inspire new inter-disciplinary perspectives on MNE–CS interactions and inform research addressing urgent societal challenges.

Résumé

Les entreprises multinationales (Multinational Enterprises - MNEs) et la société civile (Civil Society - CS) interagissent de nombreuses manières à travers les pays, avec des conséquences significatives pour ces acteurs et pour la société en général. Nous passons en revue 166 études sur les interactions entre les MNEs et la CS, publiées au cours des trois dernières décennies dans des revues spécialisées en affaires internationales, gestion générale, management et société, sciences politiques, sociologie, et management des organisations à but non lucratif. Nous synthétisons cette littérature abondante et fragmentée afin de caractériser la nature (coopération ou conflit) et le contexte (géographie, secteur d'activité et problématique) des interactions MNE–CS et de découvrir leurs antécédents, leurs conséquences et leurs modérateurs. Notre revue révèle d’importants angles morts dans notre compréhension des antécédents et des conséquences des interactions MNE–CS, et met en évidence une divergence substantielle entre les contextes des interactions MNE–CS dans le monde réel et les contextes examinés dans la littérature. Nous proposons des recommandations concrètes pour (i) mieux indiquer et élargir les contextes dans lesquels les interactions MNE–CS sont étudiées; (ii) enrichir la compréhension des antécédents des interactions MNE–CS en s’appuyant sur des perspectives institutionnelles et culturelles ; (iii) réorienter la recherche sur les conséquences des interactions MNE–CS en examinant la dynamique temporelle de l’apprentissage et de la légitimité des MNEs, et (iv) mettre l’accent sur la pertinence sociétale, telle qu’elle se reflète, par exemple, dans les capacités vertes et les marchés moraux. Nous espérons que cette revue inspirera de nouvelles perspectives interdisciplinaires sur les interactions MNE–CS et éclairera la recherche portée sur les défis sociétaux urgents.

Resumen

Las empresas multinacionales (MNEs por sus iniciales en inglés) y la sociedad civil interactúan de muchas diversas maneras en diferentes los países, con consecuencias significativas para estos actores y para la sociedad en general. Revisamos 166 estudios sobre interacciones entre multinacionales y la sociedad civil en negocios internacionales, administración general, empresa y sociedad, ciencia política, sociología, y revistas especializadas en empresas sin fines de lucro publicados a lo largo de tres décadas. Sintetizamos esta amplia y fragmentada literatura para caracterizar la naturaleza (cooperación o conflicto) y el contexto (geografía, industria y tema) de las interacciones entre las multinacionales y la sociedad civil y descubrir sus antecedentes, resultados y moderadores. Nuestra revisión revela importantes vacíos en nuestra comprénsion de los antecedentes y resultados de las interacciones entre empresas multinacionales y la sociedad civil y destaca una discrepancia sustancial entre los contextos de estas interacciones en el mundo real y los contextos examinados en la literatura. Proponemos recomendaciones prácticas para (i) indicar mejor y ampliar los contextos en los que se estudian las interacciones entre multinacionales y la sociedad civil; (ii) enriquecer la comprensión de los antecedentes de las interacciones entre las multinacionales y la sociedad civil utilizando perspectivas institucionales y culturales; (iii) reorientar la investigación sobre los resultados de las interacciones de las multinacionales con la sociedad civil examinando la dinámica temporal del aprendizaje y de la legitimidad de las empresas multinacionales, y (iv) enfatizar la relevancia social reflejada, por ejemplo, en las capacidades verdes y en los mercados morales. Esperamos que esta revisión inspire nuevas perspectivas interdisciplinaras sobre las interacciones entre las empresas multinacionales y la sociedad civil y sirva de base para la investigación sobre los desafíos sociales urgentes.

Resumo

Empresas multinacionais (MNEs) e sociedade civil (CS) interagem de diversas maneiras em diferentes países, com, consequências -significativas tanto para ambos esses atores como para a sociedade em geral. Neste artigo, revisamos 166 estudos sobre interações MNE–CS publicados em revistas especializadas em negócios internacionais, administração geral, empresas e sociedade, ciência política, sociologia e gestão de organizações sem fins lucrativos longo dase três últimas décadas. Sintetizamos esta ampla e fragmentada literatura para caracterizar a natureza (cooperação ou conflito) e o contexto (geografia, setor e problemática) das interações MNE–CS e desvendar seus antecedentes, consequências e moderadores. Nossa revisão revela importantes lacunas na nossa compreensão dos antecedentes e consequências das interações MNE–CS e sugere uma discrepância substancial entre contextos das interações MNE–CS do mundo real e os contextos examinados na literatura. Propomos recomendações concretas e práticas para (i) melhorar a identificação e abrangência dos contextos em que interações MNE–CS são examinadas; (ii) enriquecer a compreensão dos antecedentes de interações MNE–CS, utilizando perspectivas institucionais e culturais; (iii) reorientar a pesquisa sobre as consequências das interações MNE–CS, examinando a dinâmica temporal da aprendizagem e legitimidade das MNEs, e (iv) enfatizar a relevância social como refletida, por exemplo, em capacidades verdes e mercados morais. Esperamos que esta revisão inspire novas perspectivas interdisciplinares sobre interações MNE–CS e informe pesquisas que abordam desafios sociais urgentes.

摘要

不同国家的跨国企业 (MNE) 和公民社会 (CS) 以多种方式互动。这些互动 对这些参与者和更广泛的社会产生重大影响。我们回顾了 30 年来国际商务、管理学、商业与社会、政治学、社会学和专业非营利组织期刊中 166 项关于MNE–CS互动的研究。我们综合了这些庞大而零散的文献,以描述MNE–CS互动的本质(合作或冲突)和情境(地理、行业和话题), 并揭示其前因、结果和调节因素。我们的综述发掘了我们对MNE–CS互动的前因和结果的理解中的重要盲点, 并揭示了现实世界MNE–CS互动的情境与文献中所研究的情境之间的重大差异。我们提出了可行的建议,以 (i) 更好地指出和扩展MNE–CS互动研究的情境;(ii) 运用制度和文化视角丰富对MNE–CS互动前因的理解; (iii) 通过研究跨国企业学习和合法性的时间动态,重新定向对MNE–CS互动结果的研究,以及 (iv) 强调反映在例如绿色能力和道德市场的社会相关性。我们希望这篇综述将激发关于MNE–CS互动的新的跨学科视角, 并为解决紧迫的社会挑战的研究提供信息.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Civil society is defined as an area of organization, separate from both the state and the market, where individuals coalesce to take sustained action in pursuit of common interests. It comprises a diverse set of actors, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), grassroots organizations, community groups, trade unions, charitable and faith-based groups, as well as looser networks such as social movements (World Bank, 2000, 2007). Civil society actors have been frequently proposed as emerging actors on the international stage and in need of more attention as they increasingly affect the global business context (Buckley et al., 2017; Montiel et al., 2021; Teegen et al., 2004).

Civil society actors may enter spaces traditionally “owned” by market actors (Teegen, 2003), and comparative studies suggest that they play material roles in effecting cross-country differences in firms’ regulatory contexts (Bartley, 2003; Vasi, 2009). For MNEs specifically, civil society has manifested in both contentious targeting and collaborative action (Yaziji & Doh, 2009). For instance, an international activist campaign was launched in 1986 to pressure Royal Dutch Shell to divest from South Africa during the racist apartheid regime (Minefee & Bucheli, 2021), and civil society works together with MNEs such as Tesco or the Body Shop in the Ethical Trading Initiative, a multi-stakeholder partnership that aims to improve working conditions worldwide in a variety of industries (ETI, 2018). Such interactions with civil society actors can bring both substantial challenges and opportunities for MNEs, and studies demonstrate that civil society can impact MNEs’ transaction costs (Vachani et al., 2009), influence their liability of foreignness (Oetzel & Doh, 2009), shape their strategic decisions (Durand & Georgallis, 2018), and ultimately impress upon financial returns (Henisz et al., 2014).

The growing importance of civil society has led to a proliferation of studies of MNE–CS interactions rooted in a variety of research traditions, including international business, management, business and society, political science, sociology, and non-profit studies. These fields have examined the topic from different perspectives. Typically, IB and management scholars take firms as the focal actor and emphasize the implications of interactions with civil society for the MNE. The sociology and political science fields, in contrast, view civil society as the focal actor and emphasize the institutional context and power dynamics that shape civil society actors’ relations with MNEs. Finally, the nonprofit field focuses more on specific cases of cross-sector collaboration and conflict, positioning civil society actors at center stage in the analysis.

While reflective of the interests of the respective fields, these distinctive foci have also resulted in fragmentation of the literature. Therefore, nearly two decades after Teegen et al. (2004) called attention to civil society’s importance for IB research, there is still a possibility that scholars studying MNE–CS interactions will be blinded by an incomplete understanding of the same “elephant”. A systematic mapping of this literature is needed to consolidate findings on the range of interactions between MNEs and civil society, and to sow the seeds for a scholarly agenda that more explicitly connects IB theories with related disciplines examining this phenomenon.

The goal of our review is to consolidate the fragmented literature on MNE–CS interactions by specifying its conceptual and empirical bases and calling attention to critical blind spots. In so doing, we aim to highlight promising future research avenues and opportunities for more programmatic investigation to advance the potential of IB research in this domain. Our review focuses specifically on understanding interactions between MNEs and civil society actors. Studies included in our review examine, for example, the influence of local social movements on MNEs’ foreign investments (e.g., Soule et al., 2014), the engagement of MNEs with NGOs across geographical contexts (e.g., Kourula, 2010), and global business governance where civil society plays a role (e.g., Pope & Lim, 2020).

We review 166 articles published in 41 journals covering a period of more than three decades. Several key findings and missed opportunities emerge from our review. First, MNE–CS interactions are mostly studied in the context of resource-intensive industries, developing economies, and within host-country environments. Yet, there is limited knowledge on how country context affects the nature and outcomes of MNE–CS interactions across countries. Furthermore, by juxtaposing the countries where MNE–CS interactions frequently take place with those most often studied in the literature, our review illuminates understudied contexts. Second, most research on antecedents of conflictual MNE–CS interactions focuses on the (direct or indirect) negative impacts of the MNE, a rather narrow approach that does not fully explain why some MNEs are targeted by civil society while others are not, or why activists choose to target MNEs rather than other actors. Third, the study of consequences of MNE–CS interactions tends to focus mostly on MNE outcomes such as firms’ nonmarket and internationalization strategies. Less is known about other important outcomes for the MNE, and even less on societal outcomes – a surprising observation given that many MNE–CS interactions occur precisely to address societal problems. Finally, we observe that even when dealing with phenomena central to IB research, many articles do not mobilize IB theories and the proliferation of perspectives used to address MNE–CS interactions has not advanced connectivity between IB theories and those of related disciplines.

We conclude our review by suggesting avenues for future research. First, we offer a mapping of opportunities to expand the diversity of contexts in which MNE–CS interactions are examined, and provide suggestions to further explore the role of context in MNE–CS interactions. Second, we discuss opportunities for advancing knowledge on the antecedents of MNE–CS interactions by paying attention to the conditions that these actors find themselves in across different countries. Third, we propose that researchers broaden the range of MNE outcomes examined to shed light on the dynamics of MNE learning and contextual limits of MNE legitimacy in light of relevant MNE–CS interactions. Fourth, we offer suggestions for studying green capabilities and moral markets as outcomes of MNE–CS interactions and call for more attention to the study of outcomes related to crucial social issues that help address the most pressing issues facing the world today.

Literature review process

To review the research on MNE–CS interactions, and in line with other comprehensive literature reviews (e.g., Aguilera et al., 2019; Nippa & Reuer, 2019), we followed a systematic procedure that consisted of three stages: planning, data collection, and analysis.

Planning

During the planning stage we clarified key constructs and calibrated the overarching goal of the review. Following a careful assessment of previous research, we defined civil society in a way that integrates elements commonly used in prior conceptualizations. First, civil society is a sector separate from both the market and the state (Malena & Finn Heinrich, 2007). Second, civil society is characterized by collective or coordinated action (Teegen et al., 2004), as individuals unite around common interests to achieve outcomes typically not achievable by any individual alone (Olson, 1971). Third, civil society is delimited to cases where collective action is enduring, thus excluding events of an ephemeral nature such as single isolated protest events (Georgallis, 2017). Following this conceptualization, our review departs from earlier work in international business that focuses explicitly and exclusively on NGOs (e.g., Teegen et al., 2004) by including the diversity of actors that characterize the realm of civil society (Table 1 includes illustrative examples that showcase the broad range of civil society actors and of MNE–CS interactions). The review is also distinct from a recent review of institutional complexity and nonmarket strategy by Sun et al. (2021) which has a different focus (see Appendix A for details). Our overarching goal is to review studies of MNE–CS interactions, regardless of where these interactions occur and the form they take. We elaborate on the inclusion criteria below.

Data collection

Iterative pilot searches and discussions among the team of authors guided the process of journal selection, search, and article inclusion strategy. These are discussed below and summarized in Fig. 1.

Journal selection. Consistent with the goal of comprehensively assessing MNE–CS interactions, we selected articles from a wide range of leading journals in relevant fields. First, following earlier reviews at the interface between society and international business (Pisani et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2021), we started with three journal categories: international business journals, general management journals, and business and society journals. The journal selection for these three categories was the same as Pisani et al. (2017) because we expected MNE–CS interactions to be published in the same journals covering research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and international business. The only exception is that we added the recently launched Journal of International Business Policy to the IB journals category. Second, because civil society has often been studied in sociology and political science journals, we added a fourth journal category, selecting relevant journals as identified in Burstein and Linton’s (2002) seminal article. Finally, given their relevance to the topic, we added three specialized non-profit journals (Voluntas, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly and Mobilization) as a fifth journal category. This resulted in a comprehensive selection of journals, fitting with our aim of gathering the dispersed insights on MNE–CS interactions across research areas and disciplines. The full list of journals is available in Appendix B. A pilot search showed very few relevant articles before 1990, so we confined our sample to the period 1990 until 2020.

Search. We systematically searched these journals with an inclusive set of keywords that resulted from the planning stage to account for a variety of civil society actors, including formally constituted NGOs, other charitable, faith-based, labor and community organizations, activist groups, and broader social movements. Furthermore, to capture civil society topics relevant to IB and not business in general, we included additional keywords reflecting international components to the search terms used for the non-IB journals (Sun et al., 2021). The full search string employed is available in Appendix C. We searched the titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles published within our timeframe using Scopus and Web of Science, resulting in an initial set of 1372 articles.Footnote 1

Inclusion criteria. We manually inspected each article and assessed its fit with the scope of the review by reading the article abstract, or the full text when the abstract was indeterminate. An article was included if three criteria were strictly met: (i) the article examined an MNE actor, defined as “an enterprise which owns and controls activities in different countries” (Buckley & Casson, 1976, p.1), (ii) the article studied a civil society actor, and (iii) the article discussed a relational action taken by one of the two actors (either the MNE or the civil society actor), directed at the other actor. Such direct relational actions include instances such as MNEs being pressured to divest from countries with oppressive regimes (e.g., in South Africa during the apartheid regime) and MNEs collaborating with multiple civil society actors to improve working conditions in the global supply chain (e.g., the Ethical Trading Initiative). We included articles on MNE–CS interactions regardless of where they occur: the home country, the host country, or on the global level. In other words, if articles involved MNEs, we considered them to be pertinent to the domain of international business and to our review. All in all, this process resulted in a database of 166 articles on MNE–CS interactions.

Analysis

We iteratively analyzed this database, first by coding substantive elements such as primary theoretical perspectives and methodology, as well as descriptive data such as the publication year and journal. Regarding the classification of primary theoretical perspectives, we proceeded abductively: we started with a classification of theoretical perspectives from an earlier review in JIBS (Meyer et al., 2020). As new insights on employed theories emerged inductively from reviewing the articles, we iteratively modified our classification to ensure continued fit with this body of literature. Regarding the classification of methodologies, we distinguished articles as empirical (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) or conceptual (literature reviews, theory development articles, introductions to special issues and perspective or essay articles).

Next, we focused on iteratively developing an analytical framework to organize and integrate research insights. Considering our aim to synthesize knowledge on MNE–CS interactions, we were interested in what has been empirically examined (rather than just theorized) and therefore we limited this part of the coding to the 109 empirical articles of our dataset. Specifically, we followed the ‘antecedents–phenomenon–consequences’ logic (Pisani et al., 2017) as the focus of this review is on a phenomenon (MNE–CS interactions) and our interest was in uncovering what we know and what we do not know about the drivers and outcomes of this phenomenon. We coded the antecedents, specific characteristics, and the outcomes of the interaction. Key insights, emerging themes, and ideas identified through coding the articles were discussed on a regular basis by the team of authors.

Several important insights emerged inductively from this coding process. We observed that articles could be generally distinguished by the nature of the interaction studied (e.g., whether the interaction was conflictual or cooperative). We further observed that studies emphasize the importance of context, both as the background of MNEs’ activity and as a moderating condition of the relationships studied. Many studies focus on or explicitly examine moderators that condition the link between MNE–CS interactions and outcomes. Based on these insights, our coding was refined to account not only for the antecedents and outcomes of MNE–CS interactions but also for their nature, context, and moderators.

Regarding the nature of the phenomenon, we coded MNE–CS interactions as having either a conflictual nature, such as boycotts and protests, or a cooperative nature, such as donations and collaborations, in line with Odziemkowska (2022). There were also studies that looked at both conflictual and cooperative interactions, so our coding scheme allowed us to capture both conflictual and cooperative interactions as separate constructs in each article.

Many articles suggest context as an important theme for MNE–CS interactions. Indeed, studied interactions often showed similarities and common patterns in the economic development level of countries, the geographic context of the interaction, the industry, and the societal issue being examined. Therefore, we coded the country where the interaction took place for those studies that clearly identified this feature in the empirical sample. We then categorized countries using the United Nation’s country classifications of developed, in transition, and developing economies (United Nations, 2020). In addition, studied MNE–CS interactions appeared more prevalent in some industries than others, so we coded the industry in which the MNE operated using the Global Industry Classification Standard (GCIS).Footnote 2 Furthermore, we coded whether the interaction took place within (i) the MNE’s home country, (ii) the host country, (iii) the home and host country, or (iv) a global scope (for example, MNE–CS interactions in global governance initiatives). Finally, following the codebook from The Comparative Agendas Project (Baumgartner & Jones, 2002), we coded the societal issue(s) (e.g., civil rights, labor, environment) relevant to the MNE–CS interaction.

Finally, we coded the antecedents, outcomes, and moderators of the MNE–CS interactions. The antecedents were coded as being a driver for initiating the interaction on the part of either the MNE or the civil society actor. The outcomes were initially coded as outcomes for the MNE or for the civil society actor, outcomes for the interaction itself (e.g., outcomes for a multi-stakeholder initiative), outcomes for the external business environment (e.g., outcomes that impact the actors within the business environment surrounding the MNE such as its suppliers), and, lastly, outcomes for society at large. We did not treat the latter two as mutually exclusive because an outcome can be both relevant to the external business environment and society at large (e.g., studies that examine the impact of MNE–CS interactions on workers’ rights in supplier firms). Finally, we coded moderators that influenced the relationship between the MNE–CS interaction and its outcomes. An example of such a moderator is non-recoverable investments which can impact the link between conflictual interactions and how MNEs respond to them (Meyer & Thein, 2014). The moderators were coded accordingly and classified into three categories: MNE characteristics, CS characteristics, and country and issue characteristics.

Findings on MNE–civil society interactions

Overview of the literature

Trends and disciplinary origins

The data collection resulted in 166 articles on MNE–CS interactions. As illustrated in Fig. 2, research on MNE–CS interactions rose sharply since about 2008. Approximately two-thirds of this research has been published in the last decade (2010–2020). Close to 57% of this research is published in journals from the Business and Society category, compared to 22.3% in the International Business category and 11.4% in the General Management category. This observation is not surprising given that the Business and Society category includes journals publishing more articles per year. However, it also reflects the reality that earlier calls indicating the importance of civil society for IB research (e.g., Doh et al., 2010; Teegen et al., 2004) only recently began to bear fruit. Indeed, for the IB journal category, 75.7% of the articles were published in the last 10 years. Finally, approximately 9% of the articles were from the last two journal categories (Specialized Nonprofit Journals, and Sociology and Political Science). The relatively low percentage of articles from these categories suggests that while civil society actors are frequently examined in these literatures, their direct relations with MNEs may be of less interest, or are less commonly emphasized, in research published in these journals.

Theoretical and methodological foci

Table 2 shows the primary theoretical perspectives of the reviewed studies. Most articles adopt either a stakeholder or institution-based perspective in their examination of MNE–CS interactions. Only a small percentage builds primarily on international business theories, even though MNEs are central actors in these studies. Nonetheless, the general observation is that the field is characterized by considerable theoretical pluralism. As we coded up to two theoretical perspectives for each article, we were also able to examine co-occurrence of theories and observed that few papers made explicit connections between IB perspectives and theories from adjacent disciplines to study MNE–CS interactions. Finally, considering that sociology and political science have a long tradition and well-established theories to study civil society actors, it was surprising to see that a mere 11.3% of the papers draw substantially from sociological perspectives and 7.9% from political science perspectives. We elaborate on the ‘missing’ connections between IB and these other disciplines and propose remedies in the discussion section.

Of the papers we collected, 109 are empirical studies. Among these empirical papers, a large majority, namely 73.4%, are based on qualitative research and 22.9% are based on quantitative research. This overall discrepancy is largely due to the Business and Society category, where qualitative studies constitute the majority. In comparison, the General Management, International Business, Sociology and Political Science, and Specialized Nonprofit Journals categories are characterized by a more equal distribution between quantitative and qualitative studies. Finally, only around 3.7% of the empirical studies in our sample followed a mixed methods approach.

Nature of interactions

We found a roughly equal share of studies examining conflictual and cooperative interactions. A small minority of articles (8%) analyzed both conflictual and cooperative interactions in the same study. For conflictual interactions, research showed multiple tactics used by civil society in targeting MNEs, including demonstrations (Friedman, 2009), naming and shaming campaigns (Zhang & Luo, 2013), blocking MNE operations (Widener, 2007) and boycotts (Fassin et al., 2017). Research on cooperative interactions included donations (Jamali & Keshishian, 2009), collaborations on cause-related marketing initiatives (Singh & Duque, 2019), corporate volunteer programs (Caligiuri et al., 2013), local partnerships (Ritvala et al., 2014) and global multi-stakeholder initiatives (Kolk & Pinkse, 2007).

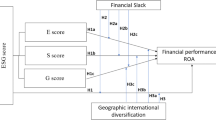

Figure 3 presents a stylized model of MNE–CS interactions that reflects our findings. We synthesize the literature by first presenting insights on the context of these interactions, and then on the antecedents and outcomes of our phenomenon of interest. Finally, we present moderators that condition the link between conflictual or cooperative interactions and outcomes, as indicated in the literature.

Context of MNE–CS interactions

Geographic context

One important dimension of MNE–CS interactions is whether they take place in the home country, in the host country, or are of global scope. We observe that most studies examine MNE–CS interactions that take place in an MNE’s host country (about 52%), while fewer studies examine interactions in the home country, or interactions that take place in both home and host countries, or on a global level. From the studies that state the country (or countries) where the interaction takes place, most (61.2%) examine MNE–CS interactions in developing economies. Approximately 34% of the studies examine MNE–CS interactions in developed economies and 4.5% of the studies examine interactions in economies in transition. Some studies examine interactions in multiple types of locations, such as in both developing economies and economies in transition.

To better understand the extent to which the geographical distribution of MNE–CS interactions examined in our review is consistent with patterns of actual interactions taking place around the globe, we collected data from GDELT (Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone), the largest and most comprehensive database of such events. We coded any event that reflected an interaction between an MNE and a civil society actor. Consistent with recent work in this area, we purposely selected actors based on their description in the GDELT codebook (in this case civil society actors) and adjusted for event count bias (Odziemkowska & Henisz, 2021).Footnote 3 Figure 4 shows particularly interesting patterns. First, it is clear that the interactions examined in the reviewed literature are not fully representative of actual interactions in practice (data from GDELT), which suggests conscious or unconscious bias in authors’ selections of sites. Countries such as the United States, China and India are disproportionally studied, while others such as Canada, Chile, or Indonesia show disproportionate MNE–CS action on the ground relative to studies of these settings. We elaborate on the implications of the global distribution of these discrepancies in the discussion section.

Note: Discrepancy between representative countries where actual MNE–CS interactions take place and countries studied in the literature as the context for MNE–CS interactions.Footnote

Studied interactions are based on articles that clearly specify the location where the interaction takes place. Actual interactions are based on the GDELT database.

Discrepancy is captured by the difference between the percentage of MNE–CS interactions in a specific country (over all interactions globally) and the percentage of studies that examine interactions in that country (over all studies in our review). Countries that are overrepresented (underrepresented) in the literature as contexts of MNE–CS interactions appear with negative (positive) valuesGap between practice and research on MNE–civil society interactions

Industry context

Industry is an important dimension of context as those industries perceived to negatively impact local community well-being – such as in the oil and mining sectors – are more scrutinized by civil society (Maggioni et al., 2019). When classifying studies according to the GCIS industry classification, we see that MNE–CS interactions are mostly studied in raw material industries (40 studies), followed by discretionary consumer goods (32 studies), food and other staples (21 studies), and energy (19 studies).

Issue context

Finally, MNE–CS interactions often relate to certain societal issues. Arguably all research included in the present review relates to some extent to societal challenges, given the presence of civil society actors; however, certain focal issues are predominant. Environmental issues are by far the most common (52.3%), followed by issues related to labor (33.9%). This aligns with the above result that most of the MNEs examined are from the energy, mining and raw materials, and discretionary consumer goods industries, where environmental and labor issues predominate. Other issues such as education, health, civil rights, or social welfare were found less frequently, and few studies examined interactions related to multiple issues (e.g., Berry, 2003; Gedicks, 2004).

Antecedents of MNE–CS interactions

Our review identified a variety of antecedents of both cooperative and conflictual MNE–CS interactions. The main antecedents of conflictual interactions include the societal impact of MNEs, MNE prominence, and institutional resonance. Antecedents of cooperative interactions include a need for legitimacy and resources for both MNEs and civil society and risk management for MNEs. These antecedents are explained in more detail below.

MNE societal impact

Research on conflictual MNE–CS interactions shows that conflict usually originates as a response to an MNE’s negative impact on society, and these conflictual interactions are typical in specific industry and geographical contexts. MNEs that operate in industries with high perceived environmental impact – particularly those using natural resources such as the forestry and the oil and mining industries – are often involved in both international disputes and local conflict with civil society actors (e.g., Fotaki & Daskalaki, 2021; Joutsenvirta & Uusitalo, 2010). This area of scholarship mostly examines interactions in developing and emerging countries, where the negative environmental and social spillovers from MNE activity are exacerbated by institutional voids (Oetzel & Doh, 2009), prompting civil society to mobilize against MNEs (Gifford et al., 2010; Skippari & Pajunen, 2010). Nevertheless, MNE–CS conflict is also witnessed in developed countries, for instance where marginalized communities face significant negative spillovers due to lack of effective governmental protection (Berry, 2003; Gedicks, 2004).

Furthermore, our review shows that MNEs can face protest in response to their involvement in broader societal issues related to their foreign operations. For instance, in the late 1990s, at the peak of controversy surrounding the actions of the military junta in Burma (now Myanmar), MNEs were confronted with civil society protests in their home country, with protesters demanding that these firms divest from Burma in response to the host governments’ numerous civil rights violations (Meyer & Thein, 2014; Soule et al., 2014).

MNEs are also being held accountable by civil society for societal issues occurring outside traditional firm boundaries. These indirect or secondary effects include, for example, environmental pollution by a firm’s suppliers (Moosmayer & Davis, 2016), sweatshop practices of global clothing brands’ suppliers (den Hond et al., 2014), and the sourcing of conflict minerals associated with human rights abuses (Rotter et al., 2014). These are cases where companies are construed by civil society as responsible for issues that initially appeared outside their strict domains of accountability (Reinecke & Ansari, 2016).

MNE prominence

Firms are not targeted exclusively based upon their (negative) behaviors; larger, and more reputable firms with well-established brands are more frequently targeted for their supply chain practices. The examples of Nike and Gap in Bartley and Child’s (2014) study help illustrate this point, which is also well reflected in related work on contentiousness in markets (King & McDonnell, 2015; King & Pearce, 2010).

Institutional resonance

An MNE’s activities can also be perceived as inadequate and lead to conflict when MNEs do not invest in learning about local values and fail to connect and align with the culture or values of the local community. These findings emphasize the importance of an MNE’s institutional resonance as a potential buffer against conflict with civil society (Dhanesh & Sriramesh, 2018; Suarez & Belk, 2017).

Need for legitimacy and resources

When it comes to cooperative interactions, our review shows that a need for legitimacy and resources motivates MNEs to cooperate with civil society, and that there are specific geographical and industry contexts that increase this need. First, MNEs facing a high liability of foreignness in the host country are motivated to develop legitimacy by cooperating with civil society actors (Caussat et al., 2019). Furthermore, MNEs in high-impact industries cooperate with civil society to establish the social stability needed to pursue operations, also referred to as the social license to operate (Gifford et al., 2010; Lucea, 2010).

Research also shows that MNEs are motivated to cooperate with civil society to gain access to complementary resources (Jamali & Keshishian, 2009). Firms are more likely to collaborate with civil society actors when there is a strategic fit (i.e., complementarity) between the resources of each party; for example, companies may lack knowledge on complex societal issues in the local environment, knowledge that local civil society groups may have in abundance (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017; Kourula, 2010).

A few studies examine what motivates civil society actors to cooperate with MNEs. The main reason cited in the literature is the need for funding (Bouchard & Raufflet, 2019; Lucea, 2010). Furthermore, such actors are motivated to cooperate by a need to increase legitimacy with their financial supporters, showing that they are not merely criticizing business but are also willing to work together with reputable MNEs to effect positive change (Burchell & Cook, 2013).

MNE risk management

MNEs are frequently motivated to cooperate with civil society to avoid anti-MNE campaigns and confrontation (e.g., Burchell & Cook, 2013; Friel, 2011). Furthermore, cooperative relations with civil society provide MNEs access to information and identify early warning signs (Kourula, 2010).

Outcomes of MNE–CS interactions

Our review uncovered multiple outcomes of MNE–CS interactions. The examined outcomes of conflictual interactions include MNE’s nonmarket strategy and MNE’s internationalization strategy. The outcomes of cooperative interactions include MNE’s internationalization strategy, outcomes for MNE’s stakeholders, and outcomes of the MNE–CS interaction for broader society.

MNE nonmarket strategy

A large proportion of the research on MNE outcomes concerns nonmarket strategy as a response to pressure from civil society in the host country. This includes subsidiary political activism (Nell et al., 2015) and CSR initiatives (Park & Ghauri, 2015). For example, Khan et al. (2015) show that campaigning by civil society and religious groups pressured MNEs into spending more on CSR and aligning their CSR strategy to local norms. Generally, researchers tend to examine developing or emerging host-country contexts, as these more volatile institutional environments require MNEs to proactively negotiate legitimacy (Nell et al., 2015). Nevertheless, this can be challenging considering that local stakeholders might judge MNEs more harshly, for example by ascribing negative behavior to MNEs’ intent and positive behavior to factors outside the firm’s control (Crilly et al., 2016).

Furthermore, our review provides insights into how MNEs deploy CSR activities to respond to conflict and to the demands of civil society. MNEs have been known to respond to conflict by initiating cooperation with civil society to establish their social license to operate (Idemudia, 2018). Partnering with civil society as a response to pressure can be seen by the MNE as a way to improve its image, signaling that the company cares about the well-being of local communities (Durugbo & Amankwah-Amoah, 2019). Research further shows that CSR practices in response to conflict should be both contextualized and substantive. For example, it is important for MNEs to create participatory relationships with local civil society and gain input on their demands so as to align CSR practices to these local needs and expectations; failing to do so, for example by following a unified set of global CSR policies, can perpetuate conflict (Mzembe, 2016; Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2012).

Finally, another nonmarket strategy employed by MNEs in response to civil society protest is that of astroturfing, characterized by largely inauthentic, instrumental efforts wherein MNEs set out to mobilize actors in favor of the company through a variety of engagements including the formation of company-sponsored NGOs, lobbying and/or approaching key actors in a focal movement and persuading them to change sides (e.g., Kraemer et al., 2013; Mzembe, 2016).

MNE internationalization strategy

A few studies show that conflictual interactions can impact strategic decisions related to an MNE’s internationalization (Fassin et al., 2017; Gedicks, 2004; Özen & Özen, 2011). Specifically, such interactions can present the MNE with uncertainty when establishing foreign operations, leading the MNE to withdraw from its initial plans (Berry, 2003) or to exit the country entirely by divesting (Soule et al., 2014). Alternatively, an MNE can pursue a low-profile strategy – focused on reducing exposure in order to limit negative publicity – in response to conflict concerning its host-country operations (Meyer & Thein, 2014).

Studies of cooperative MNE–CS interactions have also identified the internationalization process itself as an important outcome, illustrating how cooperative interactions with civil society support MNEs when entering new geographic markets (Kolk & Curran, 2017; Singh & Duque, 2019). Specifically, MNEs often rely on collaborations with civil society for market entry in contexts that differ from the MNE’s home country or are characterized by institutional voids. In these contexts, acquiring legitimacy can be difficult due to the firms’ liability of foreignness. Therefore, collaboration with civil society can contribute to co-developing legitimacy (Rana & Sørensen, 2021) and may draw on collaborative capabilities in these contexts to create or substitute for missing institutions, for example in base-of-the-pyramid markets. By collaborating with civil society groups, MNEs acquire access to local resources and the knowledge necessary to enter these markets successfully (Schuster & Holtbrügge, 2014; Tasavori et al., 2016). All in all, the results show that cooperative relations with civil society can help MNEs develop a fit with the local context at market entry (Elg et al., 2008).

Outcomes for MNE stakeholders

Few studies have examined outcomes for the MNE that are related to its stakeholders, such as consumers, employees, or the civil society actors themselves. These contributions show how cooperating with civil society, for example via cause-related marketing, has the potential to contribute to favorable consumer outcomes like positive product evaluations and sustainable product adoption (Moosmayer et al., 2019; Singh & Duque, 2019). Furthermore, corporate volunteer programs have the potential to lead to more employee engagement and capability development (Caligiuri et al., 2013). For the civil society groups themselves, our review shows that corporate volunteer programs (a cooperative interaction) can have a lasting impact on their ability to serve their beneficiaries, for example by transferring knowledge to the civil society group (Caligiuri et al., 2013). On the other hand, MNE–CS collaboration can also have downsides, such as decreasing the organizational identification that civil society employees and volunteers have with their organization (Boenigk & Schuchardt, 2015).

Societal outcomes

Only a few studies address outcomes of MNE–CS interactions for the broader society. Research on multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) has examined the number of participants in MSIs as an outcome, but this may not be the best criterion for judging MSIs’ effectiveness, as stricter enforcement and higher standards can be associated with lower business participation. For example, the Global Reporting Initiative has been successful in terms of business participation in sustainability reporting but has not contributed to solving issues central to the initiative such as NGO empowerment and stakeholder influence (Barkemeyer et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2010). As far as the impact of MSIs on societal development at the local level, the little evidence we have suggests that such initiatives often fail to address the root causes of the community ills linked to MNEs’ principal pursuit of their own commercial interests (Alamgir & Banerjee, 2019; Reinecke & Donaghey, 2021). This is also evidenced in a study by Khan et al. (2010) which showed that by failing to align the initiative to the needs of local beneficiaries, Western-led MSIs aggravated local poverty. By contrast, a study of MNE–union agreements showed that they had a positive impact on workers’ rights by facilitating a successful unionization campaign in a host country where union rights are otherwise regularly violated (Lévesque et al., 2018). Overall, despite the importance of learning whether and when MNE–CS interactions solve the societal challenges for which they were founded, most studies do not measure the direct societal impacts of these interactions.

Moderators of the link between MNE–CS interactions and their outcomes

Within the reviewed literature, some studies examined conditions that moderate the influence of MNE–CS interactions on various outcomes. We classify these moderators according to their focal variables as MNE-, CS-, or country-/issue-focused characteristics and discuss them below.

MNE characteristics

Some studies find that MNE-related factors such as government ties, experience, investments, and reputation moderate the link between conflictual MNE–CS interactions and their outcome. First, scholars have studied how an MNE’s relationship with home and host governments shapes the way MNE–CS interactions develop and the outcomes they produce. More specifically, research found that both strong support from the home government (e.g., in the case of state-owned MNEs) and strong bargaining power vis-à-vis the host government can result in MNEs not (adequately) responding to civil society’s demands (Skippari & Pajunen, 2010; Villo et al., 2020). Second, research shows that prior confrontation with activist demands (den Hond et al., 2014) and learning from peers’ experiences (Özen & Özen, 2011) can impact how MNEs respond to conflictual interactions. In addition, MNEs with unique business opportunities and high non-recoverable investments are more likely to pursue low profile strategies. When MNEs are faced with a high risk to their reputation, they are more likely to respond to civil society conflict by either exiting the host country or by pursuing a low-profile strategy (Meyer & Thein, 2014). Similarly, Zhang and Luo (2013) find that those MNEs with a public commitment to CSR and a high reputation in the host country are more likely to respond quickly to civil society campaigns.

Civil society characteristics

A few studies examine how characteristics of the civil society actors themselves or of their specific demands impact the response of MNEs to a given conflictual interaction, highlighting the role of legitimacy and power. Research shows that legitimacy is an important characteristic of civil society that contributes to the ability to persuade businesses to accede to their demands (Thijssens et al., 2015), and that, in certain circumstances, local stakeholders are seen as more legitimate than international stakeholders because they are more knowledgeable about local circumstances and more representative of local interests (Oetzel & Getz, 2012). Scholars have also shown that small communities with few resources are not powerless: they can achieve concessions by MNEs via coalition-building (Berry, 2003; Gedicks, 2004) or by ensuring the issue central to their action is framed broadly and is backed by the media (Halebsky, 2006).

Country and issue characteristics

Finally, research shows how some MNEs and industries can be more vulnerable to civil society campaigns depending on the opportunity structure within a given country or issue context. For instance, a home country with a strong corporate philanthropy logic provides an ‘opening’ for civil society to elicit faster responses to conflictual interactions by MNEs (Zhang & Luo, 2013). Relatedly, civil society exploited economic vulnerabilities and cultural logics in specific European countries to successfully oppose genetically engineered products (Schurman & Munro, 2009).

Country context matters for cooperative interactions as well. Pope and Lim (2020), for example, show that countries with strong connections to international NGOs (INGOs) often have higher business participation in certification and reporting frameworks. Furthermore, countries with economic linkages to developed countries exhibit more business participation in more stringent certification initiatives, reflecting the expectations of international trading partners on supply chain monitoring (Pope & Lim, 2020). Other findings, however, reflect what has been termed ‘organized hypocrisy’, where developed countries enforce compliance to global CSR norms on developing countries while simultaneously avoiding adherence to these norms themselves (Lim & Tsutsui, 2012). Finally, while countries with less efficient governance institutions exhibit more business participation in certification initiatives, countries with efficient governance institutions exhibit more business participation in reporting initiatives (Pope & Lim, 2020). Taken together, the results from these contributions signal that powerful companies are often involved in more lenient governance initiatives.

Finally, the issue context is also an important condition that moderates the link between MNE–CS interactions and their outcomes. Specifically, MNEs are more responsive to civil society demands when the issue is perceived as salient due to its implications; for example, in a study where the issue included deadly violence in the supply chain, MNEs felt greater urgency to respond (Oka, 2018).

Discussion

Our review details how a salient and increasingly important phenomenon—MNE–CS interactions—has been captured in the last three decades within research in IB, general management and related fields. We discuss below key findings regarding the context, antecedents, and outcomes of these interactions, as well as what we see as important gaps in the literature.

MNE–CS interactions are mostly studied in the context of resource-intensive industries such as the forestry, oil, and mining industries, in developing economies, within host-country environments, and in the context of environmental and labor related issues. Furthermore, the results show that conflictual interactions are mostly studied in resource intensive and therefore high-impact industries, and while context-sensitivity is one of the hallmarks of IB research, our results reveal two important oversights related to the treatment of context in the literature. First, the review uncovered multiple contextual characteristics that explain why MNEs might respond or not (adequately) respond, choose a specific type of response, or respond quickly to civil society’s demands. Yet, little is known about how cross-country differences in civil society characteristics affect the prevalence of MNE–CS interactions and the form they take, and about the role of cultural context in shaping the outcomes of MNE–CS interactions across countries. Second, there is a clear discrepancy between the country contexts in which MNE–CS interactions are more prominently studied and the country contexts in which they take place on the ground (see Fig. 4).

The antecedents of MNE–CS interactions differ for conflictual and cooperative interactions. Cooperation is typically driven by both MNEs’ and civil society’s need for legitimacy and resources, and risk management practices by the MNE. In resource intensive industries, MNEs’ negative impact on society leads them to cooperatively seek interactions with civil society to acquire a social license to operate. In host countries, MNEs are faced with a liability of foreignness which can also trigger cooperative interactions through a need for legitimacy. Antecedents of conflictual interactions include the (negative) societal impact of MNEs’ operations or relate to MNEs’ failure to align their practices to the host country’s local culture and norms. Finally, conflict is also triggered by issues beyond MNEs’ strict accountability boundaries, such as issues occurring within MNEs’ supply chains. Overall, most research on MNE characteristics that explain why conflictual MNE–CS interactions emerge focuses on the (direct or indirect) negative impacts of these companies, a rather narrow approach given that in practice activists do not always target the most egregious offenders (King & McDonnell, 2015). Relatedly, little is known about the broader macrolevel conditions that shape whether activists will choose to target MNEs rather than other actors (e.g., the state) and how they can promote sufficient mobilization for anti-MNE campaigns.

In terms of the consequences of MNE–CS interactions, there is more consistency across the different types of interactions, as strategic outcomes for the MNE are most common across both conflictual and cooperative interactions. Specifically, firms’ nonmarket and internationalization strategies are examined in several studies (see Sun et al., 2021 for a recent review of nonmarket strategy research) as outcomes of conflictual interactions, especially in IB journals. Strategic outcomes related to MNEs’ internationalization are relevant for cooperative interactions as well, with MNE market entry being the consequence of cooperative interactions studied most frequently. In addition, research has examined outcomes for MNE stakeholders, as well as the inclusiveness and diffusion of multi-stakeholder initiatives, and country characteristics that moderate diffusion. Yet a number of blind spots in the literature surface from the results. First, the study of consequences of MNE–CS interactions has borne fruitful insights into outcomes such as internationalization and nonmarket strategy, but this focus has not been matched by other outcomes relevant for MNEs such as MNE learning or legitimacy. Second, arguably all reviewed research relates to some extent to societal challenges (e.g., environmental or labor issues), but the primary focus has been on consequences for the MNE or its direct stakeholders, with very few studies explicitly examining societally relevant outcomes of MNE–CS interactions.

Table 3 summarizes the key gaps in the literature on MNE–CS interactions, as well as a set of recommendations for how future research can address them. In developing our recommendations, we kept in mind an additional, overarching limitation that characterizes this body of literature: that explicit connections between IB perspectives and theories from other disciplines are limited. This issue is reflective of a recurrent problem in IB research; despite its natural interdisciplinarity (Cheng et al., 2009), the IB field still appears very self-reliant and self-referencing, thus needing more communication with other fields. Our recommendations suggest ways in which the study of MNE–CS interactions can extend the influence of IB beyond business disciplines, which has been relatively modest thus far (Buckley et al., 2017).

We discuss our recommendations in the next section. While not exhaustive, we hope these suggestions will guide scholars to expand knowledge of this important phenomenon, strengthen connections between IB and other disciplines, and ultimately support efforts to confront important societal challenges.

A perspective on future research

Broadening (understanding of) the contexts of MNE–CS interactions

IB scholars’ sensitivity to context can be employed to better understand the role of context and further expand the types of contexts examined in this domain of research.

Contextualizing MNE–CS interactions

There is strong potential to further comprehend the context of MNE–CS interactions by examining characteristics of a country’s civil society base, such as the size, legitimacy, power, and prominence of civil society groups (Durand & Georgallis, 2018; Kourula, 2010). Few studies have explicitly addressed how national variation in civil society attributes affects MNE–CS interactions, yet such attributes likely hold strong explanatory power for understanding the prevalence and nature of MNE engagement with civil society. For example, cross-country differences in civil society’s orientation toward conflict could help explain why MNEs are targeted in some countries but not in others, and differences in the legitimacy of civil society within a given country may explain why MNEs seek to collaborate with civil society when entering new markets (i.e., antecedents to conflictual and cooperative interactions, respectively). In addition, the anticipated costs of protests by civil society in some market contexts may outweigh such markets’ economic attractiveness (Ingram et al., 2010; Lander et al., 2023), leading MNEs to locate their operations elsewhere to avoid such interactions at the outset. More generally, the examination of civil society as a country-specific advantage or disadvantage for MNEs operating across contexts presents itself as a promising direction for future research.

National cultural context is likely to impact both cooperative and conflictual interactions between MNEs and civil society. For instance, NGOs often encourage insider activism in corporations (Schifeling & Soderstrom, 2022), but the success of bottom-up employee activism may depend on the degree of egalitarianism or power distance accepted in society, as the voices of low-level employees are less likely to be heard in hierarchical cultures. The societal issue that civil society is advocating for may also determine variation in the outcomes of MNE–CS interactions across cultures: diversity issues, for example, may resonate less in subsidiaries located in masculine cultures and civil society’s framing of climate change as threatening to future generations might elicit stronger responses from managers in countries with a long-term orientation. Overall, cultural perspectives offer rich prospects for understanding the outcomes of MNE–CS interactions across different contexts.

Finally, we see opportunities for further contextualization of MSIs, interactions that involve actors from the market, state, and civil society sectors. IB as a field, and MSIs in particular, have been criticized for their overemphasis on Western perspectives that do “not travel well outside the Anglo-American context” in which they were created (Banerjee, 2018, p. 799); in this sense, a broader cultural understanding of MSIs would be valuable. For instance, local adaptation of global MSI guidelines could be enhanced by examining how cultural distance (Shenkar et al., 2022) or, more specifically, civil society distance (Kourula, 2010) affects MSIs. Based on our review, such a line of inquiry has received little attention, despite clear promise for IB research.

Extending the contexts of studied MNE–CS interactions

Our results, together with the analysis of GDELT event data, allow us to observe the geographic settings of actual versus studied MNE–CS interactions. Figure 4 shows evidence on the discrepancy between those country contexts used in the studies we reviewed and those where MNE–CS interactions take place. The figure indicates a concerning lack of research coverage of many countries where the intensity of MNE–CS interactions is significant. Interestingly, these neglected regions include not only countries that are typically less represented in extant management research, such as countries in Latin America, the Middle East and Africa, but also in developed countries in Europe and in the Asia Pacific region.

By neglecting several regions in studying MNE–CS interactions, researchers may well be missing novel types of interactions that could yield fruitful challenges to or complements for extant theory. For example, the interactions occurring in countries disproportionally underrepresented in research could differ in nature (e.g., be more frequently cooperative) or dynamics (e.g., become cooperative after a conflictual beginning) relative to those in contexts more frequently examined. Addressing these disparities presents tremendous opportunities to develop theory about areas still understudied in this domain. If this research area is to continue to develop new and valuable insights, it is critical that we expand the contexts studied beyond the ‘usual suspect’ countries, to elucidate MNE–CS interactions occurring in diverse contexts.

Extending knowledge of the country-level antecedents of MNE–CS interactions

The negative direct impacts of MNE activities have been (over)emphasized in the literature as the main driving factor behind civil society mobilization against MNEs, while more macrolevel factors have received less attention. We discuss below two avenues to address this gap by leveraging IB research together with social movement studies – one of the “scholarly growth industries” in the social sciences (McAdam et al., 1996; cf. Leitzinger & Waeger, 2023).

Institutional configurations as antecedents of MNE–CS interactions

Configurations of institutions (Jackson & Deeg, 2008) create political opportunities (McAdam et al., 1996) that may influence the scope and success of interactions between social movements and their corporate targets, especially MNEs. This presents an opportunity for IB research on institutions to penetrate social movement studies by informing sociologists and political scientists about antecedents of MNE–CS interactions. Comparative capitalism indicating that the way civil society is configured or positioned within a particular country’s constellation of institutions may relate to activists’ decisions to target MNEs versus the state. For example, states with a liberal market economy may be inviting to MNEs, while at the same time eliciting stronger anti-corporate activism due to their market orientation. In coordinated market economies, on the other hand, activists may primarily target governments as they see the state as more responsible for addressing social ills. Overall, the question of why (or when) activists target corporations versus states is an important but markedly understudied area that IB research on institutions can help tackle.

Culture as antecedent of MNE–CS interactions

Cultural perspectives can also extend the reach of IB to explain why some civil society groups target companies per se, and why they target certain companies but not others. For example, cultural elements such as collectivism can help explain why individuals form collaborative groups to protect communities from negative environmental impacts of MNEs. And less studied cultural values such as anti-globalization sentiment (Tung & Stahl, 2018) can help explain why civil society groups target certain prominent MNEs, or address variation in their interest to collaborate with such companies. Further, the concept of cultural distance echoes parallel ideas in social movement studies regarding the importance of cultural resonance: that the framing of issues by civil society needs to resonate with the public in order to achieve mass mobilization (Bailey et al., 2023; Benford & Snow, 2000; Lander et al., 2023). International NGOs may thus intend to protest against companies on the same issue across different countries but find varying success in mobilizing locals to support their cause, depending on the degree of cultural resonance that they achieve. As such, culture can determine whether and how conflictual interactions between MNEs and civil society emerge.

Broadening the range of examined MNE outcomes

Internationalization and nonmarket strategy decisions are among the consequences most frequently studied in this literature. Below we reflect on two understudied, but important, MNE outcomes and offer suggestions on how they can be examined.

MNE learning as an outcome of MNE–CS interactions

Our review revealed the importance of experience with MNE–CS interactions (den Hond et al., 2014; Özen & Özen, 2011), yet the extent to which MNEs learn from their prior interactions with civil society actors is relatively understudied. One perspective that can be useful for studying such questions is the CSA/FSA framework (Rugman & Verbeke, 1990). An MNE’s ability to interact with civil society actors can be conceptualized as a firm specific advantage (FSA) that helps offset their liability of foreignness in host countries. Specifically, in certain host-country environments, civil society can limit MNEs’ access to country-specific advantages such as natural resources (e.g., Holden & Jacobson, 2008; Idemudia, 2018). As a result, companies must build relationships with civil society in order to access these resources. The ability to form such relationships is especially important since failing to respond well to the demands of civil society can lead to conflict (Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2012). However, how do MNEs manage and learn from civil society relationships?

IB scholars can look to stakeholder theory and leverage the concept of stakeholder influence capacity (Barnett & Salomon, 2012), which posits that a firm’s ability to improve stakeholder relations depends on that firm’s accumulated stakeholder interactions. Consistent engagement affords firms an advantage in understanding their stakeholders, managing relationships with them, and, in the process, gaining credibility in their future attempts to engage with (other) stakeholders. Our review uncovered several studies that address how firms manage relationships with civil society in specific situations, but the dynamic nature of such interactions and whether firms learn from them remains a blind spot. Examining this FSA by drawing on work on returns to stakeholder engagement is an important opportunity for future research.

The domain-specificity of experience with MNE–CS interactions is another interesting research direction. The integration-responsiveness framework would suggest, for example, that if MNE–CS interactions can generate transferable capabilities, decisions on how to handle such interactions could be more efficiently made centrally rather than at the subsidiary level. As such, stakeholder influence capacity gained through prior experience could be globally actionable. If, on the other hand, learning from interactions depends more on idiosyncratic location features than on civil society features, localization of decision making may benefit the MNE (Newenham-Kahindi, 2011). Finally, learning could be more associated with the type of issue rather than actor or location, which could reveal yet different patterns and prescriptions for practice.

MNE legitimacy and temporal dynamics

While the need for legitimacy in the eyes of civil society is one of the most studied topics by IB researchers according to our review, much less is known about the contextual limits of the legitimacy that MNEs might gain. We call for advancing research on liability of foreignness by considering how MNE–CS interactions influence the legitimacy of MNEs and their subsequent ability to manage international investment risks across different institutional contexts (Albino-Pimentel et al., 2021; Darendeli & Hill, 2016; Holburn & Zelner, 2010).

Moreover, even the most up-to-date versions of the classic MNE–host country bargaining model could benefit from a more accurate consideration of MNE–CS interactions to include host-country civil society actors as independent principals in negotiations and as members of intra- and inter-sectoral coalitions in negotiations with firms. In this, we follow Teegen et al. (2004) and Skippari and Pajunen (2010) and call for more research on how specific civil society actors or collectives of civil society actors influence firms’ ability to obtain legitimacy by negotiating formal and social licenses to operate (e.g., Dorobantu & Odziemkowska, 2017). In expanding the three-sector bargaining model of states, firms, and NGOs, scholars can bring even more nuance into the plurality of actors and perspectives within civil society – from the more formalized organizations to the more informal grassroots actors – and their role in shaping MNE legitimacy across different institutional contexts.

Finally, the temporal dynamics of legitimacy-seeking collaborations, and MNE–CS interactions more broadly, need more attention. As mentioned above, some research suggests that MNEs’ efforts to appease local civil society to gain legitimacy can, instead, lead to ongoing conflict when the MNE does not respond adequately to civil society’s demands (Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2012). Less is known, however, about how conflictual relationships can turn cooperative, or about when MNE efforts to develop legitimacy through collaborations with civil society groups prevents targeting by other, more radical groups.

Examining outcomes related to crucial social issues

The relationships between MNEs and civil society are often tightly linked to crucial societal issues (e.g., those related to the environment, labor relations, or globalization), but the examination of societally relevant outcomes is conspicuously absent from the bulk of this research. By examining MNE–CS interactions, IB research can and arguably should help tackle important real-world problems. The two specific directions for future research discussed below highlight this potential.

Green capabilities as outcomes of MNE–CS interactions

Many MNE–CS interactions are ultimately about dealing with the environmental impact of MNEs and could be associated with the development and exploitation of green or environmental capabilities (Bu & Wagner, 2016; Maksimov et al., 2019), an MNE-specific and societally relevant outcome. To develop such capabilities, MNEs must actively connect within their stakeholder environment(s) to remain aware of potential changes and sense emergent opportunities (Maksimov et al., 2019). MNE–CS interactions can be valuable sources of information to help MNEs sense and ultimately seize opportunities across different contexts (Georgallis & Lee, 2020; Teegen et al., 2004). The use of the sensing–seizing–reconfiguring framework can be adjusted to reflect not only the relevance of local connectedness (Maksimov et al., 2019), but also the crucial importance of local civil society stakeholders that provide advantages for the acquisition and exploitation of green capabilities. This approach could help extend our understanding of MNE performance outcomes of immediate relevance for society, such as companies’ environmental performance.

Moral markets as outcomes of MNE–CS interactions

IB scholars can also advance understanding of the development of moral markets, sectors that emerge to offer market-based solutions to societal problems (Georgallis & Lee, 2020). Markets for organic goods, plant-based proteins, responsible investment, or ethical fashion have all benefited from civil society’s influence, either directly on production and consumption, or indirectly on regulations, standards, and certifications (Huybrechts et al., 2023; Sine & Lee, 2009; Vedula et al., 2022). Yet this line of research has fallen short of considering the role of MNEs in the creation and expansion of moral markets across contexts. We see two opportunities for bringing MNEs front and center in these investigations.

First, civil society groups often mobilize to support market solutions to sustainability challenges, while also providing information and resources useful for companies engaging in these markets (Georgallis & Lee, 2020; Sine & Lee, 2009). Scholars could examine to what extent such actions offer knowledge advantages for subsidiaries with civil society collaborations; and whether MNEs with such collaborations have an advantage in ‘sensing’ and ‘seizing’ market opportunities that address grand challenges. Second, given that civil society groups and MNEs often hold complementary resources (den Hond et al., 2015), MNE–CS collaborations constitute an important pathway to the development and effective functioning of moral markets. All in all, we see an interdisciplinary approach that explicitly engages with the development of moral markets as an important opportunity for IB scholarship to address ‘big questions’ and ‘grand challenges’ and help solve real-world problems (Buckley et al., 2017; Montiel et al., 2021).

Conclusion

This review has identified several avenues to advance research on MNE–CS interactions, while at the same time extending the reach of the IB field and its potential to impact practice. Incorporating MNE–CS relationships in IB theorizing may help scholars better understand and predict fundamental MNE strategy and operations in value creation around the world (Buckley et al., 2017). Such understanding offers the potential to evolve perspectives central to the corpus of IB while enabling our field to play a more vital role in positively impacting broader global issues, as MNE–CS interactions are critical mechanisms to address grand challenges. Indeed, such tackling of grand challenges by the academy is what is increasingly needed for our work to be considered valuable. Business leaders and policymakers continue to seek IB scholarship that reflects current and emergent realities and offers actionable guidance to productively shape the world of the future. This review presents promising avenues for IB scholars to address this challenge.

Notes

Our review was delimited to peer-reviewed articles published in the selected journals. For interested readers, we include a selected list of contributions in other formats in Appendix D. We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

We selected actors with primary issue focus in the following categories: ENV (environment); HRI (human rights); LAB (labor); HLH (health); EDU (education); NGO (catch-all NGO category). To adjust for event count bias, we divided the number of MNE–CS interaction events by the number of all events in the country.

Studied interactions are based on articles that clearly specify the location where the interaction takes place. Actual interactions are based on the GDELT database.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Marano, V., & Haxhi, I. (2019). International corporate governance: A review and opportunities for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(4), 457–498.

Alamgir, F., & Banerjee, S. B. (2019). Contested compliance regimes in global production networks: Insights from the Bangladesh garment industry. Human Relations, 72(2), 272–297.

Albino-Pimentel, J., Oetzel, J., Oh, C. H., & Poggioli, N. A. (2021). Positive institutional changes through peace: The relative effects of peace agreements and non-market capabilities on FDI. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(7), 1256–1278.

Bailey, E., Wang, D., Soule, S., & Rao, H. (2023). How Tilly’s WUNC works: Bystander evaluations of social movement signals lead to mobilization. American Journal of Sociology, 128(4), 1206–1262.

Banerjee, S. B. (2018). Transnational power and translocal governance: The politics of corporate responsibility. Human Relations, 71(6), 796–821.

Barkemeyer, R., Preuss, L., & Lee, L. (2015). On the effectiveness of private transnational governance regimes—Evaluating corporate sustainability reporting according to the Global Reporting Initiative. Journal of World Business, 50(2), 312–325.

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), 1304–1320.

Bartley, T. (2003). Certifying forests and factories: States, social movements, and the rise of private regulation in the apparel and forest products fields. Politics & Society, 31(3), 433–464.

Bartley, T., & Child, C. (2014). Shaming the corporation: The social production of targets and the anti-sweatshop movement. American Sociological Review, 79(4), 653–679.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (2002). Policy Dynamics. University of Chicago Press.

BBC. (2022). McDonald’s and Coca-Cola boycott calls grow over Russia. March 8, 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-60649214

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639.

Berry, G. R. (2003). Organizing against multinational corporate power in cancer alley: The activist community as primary stakeholder. Organization & Environment, 16(1), 3–33.