Abstract

There has long been a dominant logic in the international business literature that multinational corporations should adapt business practices to “fit” host cultures. Business practices that are congruent with local cultural norms have been advocated as effective and desirable, while practices that are incongruent have been deemed problematic. We examine and challenge this persistent assumption by reviewing the literature showing evidence for both benefits and acceptance of countercultural practices (i.e., practices that are seemingly incongruent with local cultural norms or values), and disadvantages and rejection of local practices. Drawing on the literature reviewed, we offer four types of theoretical (ontological, epistemological, causal, and functional) explanations as to why and when countercultural business practices might be preferred. Finally, we provide a springboard for a future research agenda on countercultural practices, centered around understanding the circumstances under which businesses and local stakeholders might benefit from the use of countercultural practices based on such factors as strategic intent, local preferences, institutional drivers, and social responsibility.

Résumé

Il existe depuis longtemps une logique dominante dans la littérature en affaires internationales selon laquelle les sociétés multinationales devraient adapter leurs pratiques commerciales pour être alignées sur les cultures d'accueil. Les pratiques commerciales conformes aux normes culturelles locales ont été considérées comme efficaces et souhaitables, tandis que les pratiques non conformes ont été jugées problématiques. Nous examinons et remettons en question cette persistante supposition en passant en revue la littérature démontrant à la fois les avantages et l'acceptation des pratiques contre-culturelles (c'est-à-dire des pratiques qui sont apparemment incompatibles avec les normes ou valeurs culturelles locales), ainsi que les inconvénients et le rejet des pratiques locales. Nous appuyant sur la littérature examinée, nous proposons quatre types d'explications théoriques (ontologiques, épistémologiques, causales et fonctionnelles) mettant en lumière pourquoi et quand les pratiques commerciales contre-culturelles pourraient être préférées. Enfin, nous élaborons un tremplin pour un futur programme de recherche sur les pratiques contre-culturelles, centré sur la compréhension des circonstances dans lesquelles les entreprises et les parties prenantes locales pourraient bénéficier de l'utilisation des pratiques contre-culturelles, et qui sont liées aux facteurs tels que l'intention stratégique, les préférences locales, les moteurs institutionnels et la responsabilité sociale.

Resumen

Hace mucho ha habido una lógica dominante en la literatura de negocios internacionales que las corporaciones multinacionales deben adaptarse a las prácticas de negocios para “ajustarse” a las culturas anfitrionas. Las practicas comerciales que ha son acorde con las normas culturales normales ha sido defendidas como efectivas y deseables, mientras que las prácticas que son incongruentes han sido consideras problemáticas. Examinamos y retamos este supuesto persistente al revisar la literatura que muestra evidencia para tanto los beneficios como para la aceptación de practicas contraculturales (es decir, prácticas que son aparentemente incongruentes con la normas o valores de la cultura local), y las desventajas y el rechazo de las prácticas locales. Con base en la literatura revisada, ofrecemos cuatro tipos de explicaciones teóricas (ontológica, epistemológica, causal y funcional) sobre por qué y cuándo las practicas comerciales contraculturales puede ser preferidas. Finalmente, ofrecemos un trampolín para una futura agenda de investigación sobre las prácticas contraculturales, centrada en el entendimiento de las circunstancias bajo las cuales los negocios y los grupos de interés locales pueden beneficiarse del uso de prácticas contraculturales basada en factores, como los objetivos estratégicos, las preferencias locales, los impulsores institucionales, y la responsabilidad social.

Resumo

Há muito existe uma lógica dominante na literatura de negócios internacionais de que corporações multinacionais devem adaptar práticas de negócios para "se adequar" a culturas anfitriãs. Práticas comerciais congruentes com normas culturais locais têm sido defendidas como eficazes e desejáveis, enquanto práticas incongruentes têm sido consideradas problemáticas. Examinamos e desafiamos esta suposição persistente ao revisar a literatura que mostra evidências tanto de benefícios quanto da aceitação de práticas contraculturais (ou seja, práticas que são aparentemente incongruentes com normas ou valores culturais locais) e desvantagens e rejeição de práticas locais. Com base na literatura revista, oferecemos quatro tipos de explicações teóricas (ontológicas, epistemológicas, causais e funcionais) sobre por que e quando práticas comerciais contraculturais podem ser preferidas. Finalmente, fornecemos um trampolim para uma futura agenda de pesquisa sobre práticas contraculturais, centrada na compreensão de circunstâncias em que empresas e stakeholders locais podem se beneficiar do uso de práticas contraculturais com base em fatores, como intenção estratégica, preferências locais, motivadores institucionais, e responsabilidade social.

摘要

长期以来, 国际商务文献中有一个主导逻辑, 即跨国公司应调整商务实践以“适应”东道国文化。与当地文化规范一致的商务实践被认为是有效和可取的, 而不一致的实践则被认为是有问题的。我们通过对反文化实践 (即看似与当地文化规范或价值观不一致的实践) 的好处和采纳以及对当地实践的弊端和抛弃的文献综述证据的显示, 来检查和挑战这一持久的假设。借鉴综述的文献, 我们提供了四种类型的理论 (本体论、认识论、因果关系和功能) 解释, 以说明为什么以及何时反文化商务实践可能会被偏好。最后, 我们为未来关于反文化实践的研究议程提供了一个跳板, 中心是了解企业和当地利益相关者在何种情况下可能受益于基于诸如战略意图、当地偏好、制度驱动力和社会责任等因素的反文化实践的运用。

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An enduring question for academics and practitioners in international business and management (IB/IM) is how to account for cultural differences when conducting business across borders (e.g., Hutzschenreuter et al., 2011; Kirkman et al., 2006; Newman & Nollen, 1996; Tsui et al., 2007). The literature has addressed this question as a tension between convergence and divergence of business practices across nations (e.g., Tregaskis & Brewster, 2006), as a balance between standardization and local differentiation of practices within multinational networks (e.g., Pudelko & Harzing, 2007), and as a dual imperative of global integration and local responsiveness of business strategies (e.g., Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989).

The fundamental assumption underpinning this research is that fit between business practices and local cultures matters. Following a seminal study by Newman and Nollen (1996) focused on the link between management practices and financial performance, it has been largely argued and accepted that multinational enterprises (MNEs) must adopt practices that are congruent with local cultural norms. In general, principles like alignment and fit have a positive connotation in the field, while misalignment and misfit are often seen as problematic. The argument for fit with local cultures has been formulated in both pragmatic terms (gaining legitimacy, reducing the liability of foreignness, enhancing locals’ acceptance; e.g., Jaeger, 1986; Ma & Allen, 2009; Mezias, 2002; Rosenzweig & Nohria, 1994) and ethical reasoning (cultural sensitivity as opposed to cultural imperialism; e.g., Calvano, 2008). The discussion of fit also reflects the fact that variation in practices across cultures has been repeatedly observed over time (e.g., Brewster et al., 2004; Lazarova et al., 2008; Schuler & Rogovsky, 1998). Case studies criticizing organizational and individual failure to conform to local norms and highlighting negative consequences associated with their lack of adaptation are also common in business and management research and education (e.g., Gao, 2013; Meyer, 2015).

While the preference for fit is pervasive in the academic literature, MNEs operating in foreign countries will, at times, for strategic or other reasons, eschew cultural adaptation and intentionally or inadvertently introduce practices that are inconsistent with local cultural norms (e.g., Aguzzoli & Geary, 2014; Edwards et al., 2016; Mellahi et al., 2016; Nelson & Gopalan, 2003). Companies will sometimes adapt their products and services to fit their markets, while their management and operations practices may remain rooted in their home cultures. At times, these organizations may become true “cultural incubators” (Caprar, 2011), shaping local norms and values even beyond the boundaries of the organization (e.g., Ritzer, 2018), as they purposefully or incidentally use countercultural business practices.

The use of countercultural practices (i.e., business practices not aligned with accepted local cultural norms), however, is not featured in IB/IM studies as a legitimate topic, and, if mentioned, it is often portrayed as a failure to achieve the ideal state of cultural fit. This failure is attributed to either ignorance (i.e., MNEs being unaware of the need to adapt their practices), difficulties with implementing adaptation (i.e., MNEs are aware of cultural differences, but find it challenging to adapt their tried and tested approaches), consistency with strategic choices (i.e., MNEs pursuing a global or international strategy, as opposed to a multi-domestic or transnational strategy), or managerial incompetence. Yet, by carefully examining studies focused on understanding the role of culture in IB/IM, one can see that countercultural practices may be less problematic than expected and are even, at times, more effective than local practices. This provides an ironic twist to the cultural fit literature, as empirical studies hypothesizing fit have, instead, found support for the use of countercultural practices. As the studies were designed to test cultural fit, the unexpected results are often considered anomalies in the data. We contend that these “anomalies”, collectively, offer an important insight into an existing phenomenon that deserves attention. Not only have some studies found countercultural practices to be used but they have also, at times, found such practices to be beneficial. For instance, in a meta-analysis of the link between high-performance work systems and business performance, Rabl et al. (2014), following the standing wisdom of cultural fit in the literature, predicted that high-performance work systems would be more effective when they fit with national cultural values. What they found was quite different: the relationship between high-performance work systems and business performance was stronger and positive in countries hypothesized to be cultural misfits for this approach. Similar examples of findings that are “puzzling, counterintuitive, and contrary to what the research literature suggests” (Von Glinow et al., 2002: 133) abound in the literature.

With these considerations in mind, we conducted a review of the literature with the specific objective of identifying studies that capture (intentionally or not) instances of countercultural practices, and, in particular, instances where the use of such practices was not problematic, and sometimes, even beneficial. Both anecdotal evidence from practice suggesting that countercultural practices are common, and that multiple studies, reporting evidence that they can even be effective, signaled the need for such a review. We have discovered that countercultural practices are one of those “compelling empirical patterns that cry out for future research and theorizing” and “that, once described, could stimulate the development of theory and other insights” (Hambrick, 2007:1350). Indeed, phenomenon-driven research has been highlighted as a priority for the field (Doh, 2015) in the context of ongoing calls for fresh perspectives in IB/IM research (e.g., Buckley, 2002; Buckley et al., 2017; Delios, 2017; Verbeke et al., 2018). Our focus on countercultural practices is consistent with such perspectives, both because this is a phenomenon that exists, yet has not been explored or theorized enough, and because it problematizes a fundamental assumption in the field (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2011). Problematization (i.e., identifying, scrutinizing, and reconsidering assumptions in the field) opens opportunities to forge new perspectives that prompt fresh research questions, which would otherwise be viewed as illegitimate, if even “viewed” at all.

It seems important to clarify that we are not disputing the value of cultural adaptation: the evidence for the importance of cultural fit is overwhelming (Daniels & Greguras, 2014; Earley & Gibson, 1998; Newman & Nollen, 1996; Schuler & Rogovsky, 1998; Tsui et al., 2007). However, in light of our observation that the field has accumulated significant empirical evidence showing that countercultural practices can be effective, we argue that the predominant focus on cultural fit precludes us from acknowledging the potential value of misfit under certain conditions. In other words, our work is not meant to dismiss the importance of cultural fit, nor to condone cultural imperialism. In fact, as we show later in our discussion, when multiple stakeholders are properly considered – including, for instance, the desire of local employees to depart from certain norms of their own culture (e.g., Caprar, 2011) – what constitutes fit and what is viewed as imposing cultural norms, etc. might change.

The premise of this review is to better delineate the benefits of intentional and considerate use of countercultural practices (instead of wishing them away or treating them as an anomaly undeserving of further exploration). By recasting the literature through a more intentional frame, and by encouraging the inclusion of perspectives that go beyond the interests of the organization, this review aims to make sense of empirical findings that contradict the dominant thinking in the field. This perspective is consistent with the emergent conversation on positive cross-cultural scholarship (e.g., Stahl et al., 2016, 2017): it is meant to bring about a more balanced view on culture, refocusing attention towards generative aspects of international business challenges, as opposed to taking the usual predominantly negative view of differences, diversity, and cultural distance (Stahl & Tung, 2015). We draw attention to the need to explore countercultural practices as an inevitable (and not necessarily deleterious) reality of IB/IM, and as a phenomenon that could open new avenues for research towards a better understanding of the nuances of conducting business across borders.

It seems important to acknowledge that we emphasize a cultural lens in our review, as opposed to other theoretical lenses that have been used to explore business practices in global operations. Studies informed by neo-institutionalism (e.g., Kostova & Roth, 2002; Kostova et al., 2008), and comparative institutionalism (Jackson & Deeg, 2008; Morgan et al., 2010), along with more recent explorations of power relations in the interaction between MNEs in their context (e.g., Geary & Aguzzoli, 2016), are also revealing instances of both isomorphic and non-isomorphic developments, akin to the cultural adaptation/non-adaptation perspective. Indeed, there is continued discussion around how culture and institutions relate to each other, or which perspective is most useful (e.g., Caprar & Neville, 2012; Hatch & Zilber, 2012; Suddaby, 2010). In our review, we acknowledge and discuss the relevance of institutional pressures, but focus on studies that explore business practices in relation to local cultures.

We begin by presenting the review methodology we adopted, which had to be tailored to the peculiar case of looking for research on a phenomenon that is not uncommon, but that has not been properly recognized as a legitimate topic in the field. We then discuss in more detail why the phenomenon of countercultural practices has remained undertheorized and underexplored, despite its relevance to the IB/IM. By exploring the roots of the cultural adaptation imperative and its development over time, we show that suggestions for a more nuanced view on the interplay between culture and business practices have been formulated in the literature all along, just not properly acknowledged. We then present empirical evidence showing that countercultural practices can be effective and welcomed, and related evidence showing that adaptation is not always beneficial. Finally, we develop potential theoretical explanations for such “surprising” findings, demonstrating that they can be explained and utilized for refining and further developing theory in IB/IM. We conclude with implications for theory and practice, setting up the foundation for a research agenda on countercultural business practices.

Review Methodology

Conducting a review of studies focused on countercultural practices in a field largely informed by the imperative for cultural adaptation required a particular approach: the field has not yet recognized the focus on this phenomenon as a topic of investigation, and, as such, researchers have not deliberately pursued it. Yet, as mentioned before, many studies have inadvertently detected instances of countercultural practices. Our task was to identify these studies despite the countercultural focus not being clearly signaled. Consequently, our review approach unfolded in two phases: a scoping phase and a focused phase.

In the scoping phase, we first identified seminal articles related to the topic of cultural adaptation and its variants (i.e., convergence/divergence, differentiation/integration, localization/standardization/contextualization). We searched for articles that both presented evidence of use and impact of countercultural practices and articles providing insights into why the need to achieve fit has become “almost axiomatic” (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1986: xii), despite not always being the only (let alone best) approach in practice (e.g., Caligiuri & Tarique, 2016). The seminal articles came to our attention through various avenues: scanning major journals in the field; receiving recommendations from colleagues; examining the articles cited in identified articles; and following up with new content alerts from journals, to name but a few. This scoping phase provided us with indications as to where (i.e., what journals) and how (i.e., what keywords) we would need to search for more literature on countercultural practices. Moreover, these additional empirical studies, theoretical and conceptual articles, literature reviews, and scholarly essays were helpful in elucidating the broader research context surrounding the focus of our review. Specifically, such articles allowed us to begin building an understanding of why exactly countercultural practices have long been “missing” in IB/IM research. An understanding of the drivers of this absence is crucial if, as we indeed argue later, more research will emerge on countercultural practices in the future.

In the focused review phase, we identified relevant empirical research in leading scholarly journals. One advantage of such an approach over others (e.g., broad searches using Google Scholar) is the ease of quality control over the research being reviewed. We selected journals taking into consideration the high impact journal list conventionally recognized in recent review articles (e.g., Aguilera et al., 2019), widely accepted journal ranking systems, such as the Financial Times 50 list, and the rankings provided by the Australian Business Deans Council. We ultimately derived a list of 23 relevant journals to include in our search through this process, including leading IB journals (Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of World Business, Journal of International Management, Management International Review, Journal of International Business, Global Strategy Journal, International Business Review), leading management journals (Academy of Management Journal, Human Relations, Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Management Studies, Strategic Management Journal, Journal of Management, Journal of Business Ethics, Organization Science, Organization Studies, Administrative Science Quarterly), HRM specialty journals (Human Resource Management, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources), and cross-cultural management journals (Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, International Studies of Management & Organization). We searched each journal for articles containing keywords that could be related to countercultural practices, such as: cultural adaptation; localization; liability of foreignness, liability of localness, asset of foreignness, advantage of foreignness, disadvantage of localness; cultural sensitivity; countercultural; contextualization; local adaptation; cultural distance; cultural friction; cultural change; cultural imperialism; local culture; and local legitimacy. In terms of timeframe, we limited our search to articles published between 1980 and 2020. We chose 1980 as the lower threshold for our search as this was the year in which Hofstede’s (1980) seminal work on cross-cultural management was published, which subsequently triggered a wave of research on issues of national culture in and around organizations.

At the conclusion of this process, we had identified a total of 95 empirical studies relevant to our exploration. Of these, 22 articles provided direct evidence that countercultural practices can be beneficial (Table 1). Another set of 18 studies captured situations where countercultural practices were found to be accepted or even preferred by locals (Table 2). During our search for articles related to countercultural practices, we also identified studies capturing negative consequences or perceptions of local(ized) practices (14 studies; Table 3). We have included these studies in our review as they also support the need to think critically about the efficacy of cultural adaptation, and the importance of giving more attention to countercultural practices. The remaining 41 studies, while not directly addressing the benefits or acceptance of countercultural practices (or the disadvantages/rejection of local practices), were relevant in terms of capturing a broader related argument suggesting that foreignness is not always a liability, or that localness is not always an advantage. We discuss these articles in more detail in the section on empirical evidence. It is also important to note that at least some results supporting the use and effectiveness of countercultural practices are most likely never reported: studies with results that disconfirm formulated hypotheses (which are usually built on, and consistent with, existing perspectives) are not usually published (Rosenthal, 1979). The fact we were able to identify such a significant number of articles on the success of countercultural practices provides further justification for greater attention to this topic.

Before describing the specific pieces of empirical evidence collated through our review, we first present a broader discussion of the evolution of the cultural adaptation tenet in the field, which helps to explain why the phenomenon of countercultural practices has not been recognized as a focal topic of inquiry in IB/IM. This discussion is important to make sense of the empirical findings, which we present in the subsequent section, and for developing a research agenda focused on countercultural practices, which we do towards the end of this article.

The Rise of the Cultural Adaptation Imperative

To understand why the phenomenon of countercultural practices has not been explored as a legitimate topic in IB/IM, a useful point of departure is evaluating the theoretical context (i.e., paradigms) dominating the field. Researchers are typically incentivized to present “incremental enhancements of wide-spread beliefs” (Starbuck, 2003: 349), and, as a result, new research tends not to depart too much from accepted mainstream thinking on any given topic (see also Kuhn, 2012 [1962]). Alvesson and Sandberg (2011) argue that researchers typically generate new theory by spotting or constructing gaps in existing theories – that is, exploring opportunities to extend existing understandings, which precludes an exploration of the underlying assumptions of such understandings – the “hidden” taken-for-granted perspectives that inform, and limit, the theorizing in a domain. Such assumptions can operate at different levels: they can be shared within a particular school of thought, they can manifest as broader metaphors about a particular object of study, or even at the level of paradigms, ideology, or fields of study. They are typically hidden (i.e., implicit and unspoken), but highly consequential in shaping research perspectives (Slife & Williams, 1995). Yet, by problematizing such assumptions (i.e., identifying, scrutinizing, and reconsidering them; cf. Alvesson & Sandberg, 2011), new research questions emerge in relation to “blind spots” in a particular field. In IB/IM, the cultural adaptation imperative is based on a broader field assumption that fit is inherently beneficial. We begin by exploring this assumption about the positivity of fit (and the theories that are built around it) in more detail as an explanation for why researchers to date have focused so intently on cultural adaptation, rather than acknowledging and studying countercultural practices. We then explore in detail the development of the cultural adaptation imperative, as this further explains why the phenomenon of countercultural practices has become something of a research “blind spot”, despite, as we show later, evidence suggesting both its occurrence and potential effectiveness.

The Overall Preoccupation with Fit in IB/IM

The need to achieve fit is “almost axiomatic” in business and management theories (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1986: xii). Grand management theories, such as population ecology theory (Van de Ven, 1976), contingency theory (Donaldson, 2001), and institutional theory (Scott, 2001), are all in some way connected to the fundamental notion that organizations must fit their environments to survive. Similarly, specific key IB theories, such as the internationalization of the firm, have for a long time highlighted the liability of foreignness (e.g., Zaheer, 1995). The word “liability” primes research to focus on the negative consequences of being culturally different, a challenge to be overcome. And while recently this focus has been challenged (e.g., Edman, 2016a; Taussig, 2017), these theories have promulgated an implied assumption that fitting with cultural norms is beneficial; a development that has left less theoretical oxygen for the possibility that countercultural practices may be effective and preferred under certain circumstances.

Given our focus on countercultural practices, when we use the term “fit” we refer to consistency between business practices (broadly defined) and local cultures, rather than other uses of the term, such as organizational internal consistency, or fit between strategic choices and internal or external organizational environments in general. However, we provide a brief overview of relevant theories, that have fueled a preoccupation with fit in general, as relevant to understanding the context of the more specific cultural fit imperative.

We begin with the population ecology theory. With roots in the Darwinist “survival of the fittest” perspective, the theory suggests that some varieties of organization survive (while others become extinct) through a natural selection process like that seen in nature. Surviving populations of organizations are believed to be those that adapt best to the demands of their environment (Hannan & Freeman, 1977), with such adaptations assumed to explain both the variety and the similarity of surviving organizational forms. Contingency theory has also emphasized the need for a multiplicity of organizational forms, with no one best way to manage, but rather, a variety of approaches adjusted to the internal and external environments of the organization (Donaldson, 2001). The essence of the argument made by contingency theorists was that organizational structures that fit such contingencies produce better organizational outcomes. Institutional theory, although often portrayed to be at odds with contingency theory (Meyer & Höllerer, 2014), also promotes the fundamental principle of fit, suggesting that organizations must attain social legitimacy by adopting managerial practices that are taken for granted by other organizations in the same field (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). Specifically, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) suggested that organizations are pressured to adopt practices that are legitimated by coercive, mimetic, and normative mechanisms.

Given the prevalence of a functionalist view of fit in such organizational theories, it is unsurprising that this perspective has also come to underpin much of the thinking about how to optimize international operations. For instance, in an evaluation of the environments of MNEs, Rosenzweig and Singh (1991) emphasized the need for MNEs to adapt to the local environment, adaptation that goes beyond coercive isomorphism dictated by local regulations and economic pressures: it is posited that MNEs must also reflect values, norms, and local practices (Westney, 1993), which are, obviously, the expression (and constituents) of the local culture.

The specific analysis of the adoption of organizational practices by subsidiaries of MNEs also revealed institutional effects imposed by characteristics of the host countries (Kostova & Roth, 2002). Zaheer (1995) argued that MNEs inherently suffer from a deficiency in local legitimacy due to what the MNE literature describes as the liability of foreignness (Hymer, 1960/1976). To compensate for the disadvantage of being foreign, Zaheer (1995) recommended that MNEs should imitate local firms, as conforming to local isomorphic pressures should enhance local legitimacy. Progressively, the field has embraced the premise that foreignness is a liability, and that this liability can be overcome by imitating local firms (e.g., Salomon & Wu, 2012).

These are just a few examples of the many arguments in the field that essentially praise congruence as beneficial and label misfit as problematic. Moreover, when applied to the global context (i.e., MNEs), foreignness is cast as a largely inescapable source of misfit. While these arguments were typically formulated at the organizational level, their influence on defining business practices in general has been pervasive. We next detail the manifestation of the fundamental fit assumption in IB/IM.

The Cultural Adaptation Imperative

In this section, we trace the development of the cultural adaptation imperative in IB/IM, showing that it has a achieved a dominant position for legitimate reasons. Unfortunately, such dominance, bolstered by the aforementioned positive outlook on fit in general, has crowded out the potential for a concerted research focus on countercultural practices.

Historical thinking on global business practices

Early theorizing about effective practices across cultures did not argue in favor of local adaptation. On the contrary, the economic development of highly industrialized (i.e., “Western”) economies, and a general tendency for a self-referential perspective on culture, prompted researchers from the developed world to formulate the recommendation that other countries should “evolve” towards a similar economic philosophy. For instance, initial comparisons of management approaches in Japan and the US concluded that the Japanese approach was inappropriate, simply because it did not comply with Western principles (Harbison, 1959). Such a statement nowadays would be deemed ethnocentric, but at that time it had a powerful influence on thinking in the field, setting up a conversation about the need for, and indeed inevitability of, convergence in business practices (e.g., Kerr et al., 1960). The later success of Japanese companies (Vogel, 1979), along with early comparative management studies (e.g., Gonzalez & McMillan, 1961; Oberg, 1963) challenging the universality of Western (i.e., American) approaches, made room for an alternative view, that practices consistent with cultural traditions (i.e., divergent) were not necessarily flawed, and may even be superior to a standardized Western model (Abegglen, 1973).

It did not take long, though, for researchers to move away from such exclusive perspectives and recognize potential benefits in both views. Three ideal types of organization were conceptualized based on the original contrasting American and Japanese models (Ouchi & Jaeger, 1978): Type A (North American and Western European), Type J (Japanese and Chinese), and the mixed Type Z (a modified American model with influences from Type J). The latter type was presented as more appropriate even for the American context, suggesting the potential value of countercultural practices: the model showed that some Japanese practices were appreciated and well regarded by American workers and managers. Although not directly stated as such, we identify the Type Z organization as an early attempt to focus on identifying best practices, where (not) adapting to the local culture was not the driving criterion. A detailed review of the debate applied to the evolution of the Japanese management concluded that the best feature of the Japanese approach was being “a flexible, innovative process of choice; it is understood that cultural values are only one important factor in achieving goals” (Dunphy, 1987: 454). This characterization seems to summarize very well what, later, Ralston et al. (1993) defined as “crossvergence”, a perspective that clearly attempted to reconcile the convergence (standardization) and divergence (localization) perspectives. The concept was further developed in subsequent studies including one that won the Journal of International Business Studies’ 2007 Decade Award; for an overview, see Ralston 2008), but the imperative for cultural adaptation continued to be reflected in most IB/IM studies, including those who cite this prominent work.

The cultural turn

The conversations around convergence and divergence of business practices were paralleled by increasing interest in cultural specificity (Laurent, 1986), an interest that perhaps can be attributed to Hofstede’s (1980) extremely popular study on culture’s consequences, which emphasized differences in national cultures. A coherent model of cultural fit was soon proposed (Kanungo & Jaeger, 1990; Mendonca & Kanungo, 1994), emphasizing the importance of the socio-cultural environment in defining an organization’s work culture and related human resources practices. An avalanche of theoretical models and empirical results followed that advocated the idea of fit between business practices and national cultures. For instance, Earley (1994) suggested in an experimental study that group-focused training would be more effective for collectivistic individuals, while self-focused training would be more effective for individualistic people. Kirkman and Shapiro (1997) proposed that the success of self-managing work teams in foreign subsidiaries may depend on how MNEs effectively reduce the culture-based resistance of local employees. Chen et al. (1998) also suggested that organizations are likely to effectively foster cooperation within a firm when organizational arrangements are well aligned to employees' cultural values.

From cultural sensitivity to cultural imperative

As evidence supporting the idea of cultural fit accumulated, researchers returned to testing the earlier model of cultural fit, further emphasizing the relevance of culture to business and management (e.g., Aycan et al., 2000). However, the study that seemed to have shaped the thinking in the field, often cited by most studies related to the topic, is the seminal piece by Newman and Nollen (1996): they directly tested the overall relationship between management-culture fit and performance, concluding that business performance is superior when management practices are congruent with the national culture. Consequently, they unequivocally recommended that management practices must be adapted to local cultures, a view that became central to the field of IB/IM. It is worth noting that Newman and Nollen’s (1996) study has been cited much more often in comparison to the earlier articles (e.g., Dunphy, 1987; Ouchi & Jaeger, 1978) proposing a more complex approach to culture fit.

Recent insights related to cultural adaptation. Pudelko and Harzing (2007) explored the presence of fit in a study of human resource management (HRM) practices in foreign subsidiaries. Using a large-scale sample of multinationals originating in the US, Japan, and Germany, along with their subsidiaries in these countries, Pudelko and Harzing (2007) tested the two dichotomies of HR practice implementation: convergence versus divergence, and standardization versus localization. In their study, standardization is the implementation of the convergence perspective, and localization reflects the divergence view. They further delineated standardization in two ways. One is the country of origin effect, which emphasizes the importance of maintaining headquarters’ practices across subsidiaries globally. The other is the dominance effect, in which “global” (often US-based) best practices are implemented around the world. While the country of origin and the dominance effects are both versions of standardization (and, therefore, in opposition to localization), the prevalence of the dominance effect implies the existence of global best practices. In addition, the dominance effect was also found to be increasing over time among the organizations studied. Research has also concluded that certain HRM practices are more likely to be bound to national-level institutional forces, requiring a higher level of divergence across countries, whereas other HR practices can be adopted similarly across countries, enabling convergence (Farndale et al., 2017).

The aforementioned findings provide especially useful insights into which HRM practices will likely vary across subsidiaries and which will be standardized. However, these findings do not allow for inferences regarding why the converging dominance effect is observed more often (and increasing over time), and implicitly does not allow for theory-based prescriptions. Moreover, the fact that dominance is stronger, and convergence is present, does not necessarily highlight the fact that these might be positive developments. However, based on the observation that most local subsidiaries converge towards a dominant model, Pudelko and Harzing (2007) concluded that “there is less need to localize than frequently believed” (2007: 553). We acknowledge this insight as critical, and consistent with our view that the cultural fit imperative needs to be explicitly challenged and better investigated for strategic nuances to emerge.

Empirical evidence of countercultural practices

While IB/IM theory evolved towards confirming the need to adapt practices to local contexts, many companies have continued doing what they know best: implementing practices that work in their home countries (standardization by the country of origin effect), or practices thought to be universally effective (standardization by dominance). Whether such approaches are intentional or just a result of inability (or unwillingness) to adapt is not the focus of our investigation. What is important is that such practices represent a reality of global business that remains largely unexplored in the field.

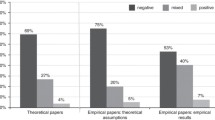

It seems important to reiterate that the empirical evidence supporting the use of countercultural practices shows up (most often “uninvited”) in studies aimed at validating the cultural fit imperative. In such studies, researchers sometimes serendipitously capture surprising findings: the expected positive effect of culturally congruent practices are not confirmed, while approaches that could qualify as perfect cases for “what not to do” do not have the expected detrimental outcome and may even have positive effects. Overall, the accumulated findings (summarized in Figure 1) suggest that the cultural adaptation imperative needs to be scrutinized, or at least supplemented with additional perspectives, which is an opportunity to further develop our understanding of the role of culture in international business, and to better define what constitutes “effective” IB/IM practices.

Benefits of Countercultural Practices

Many of the studies we identified presented some evidence that countercultural practices can be effective (i.e., have positive outcomes for organizations and/or employees). Such findings were often presented as contradicting hypotheses formulated based on existing theory (i.e., generally linking back to the dominant thesis of fit), and/or “tucked behind” more prominently discussed findings evidencing the efficacy of cultural adaptation. The 22 studies in this category are listed in Table 1, along with a summary of relevant findings from each study. Further analysis of these studies allowed us to see commonalities across them in terms of the type of management practice studied, which in turn facilitated the distillation of three broad themes: studies focused on leadership/management style and personnel; studies focused on human resource systems and practices; and studies focused on organizational culture and climate. We further discuss these themes below, and the studies associated with each of them.

Beginning with leadership/management style, we identified several studies demonstrating the efficacy of seemingly culturally incongruent leadership or management approaches. In a cross-cultural study of retail employees in China and Canada, Fock et al., (2012) found that the positive effect of empowering leadership on job satisfaction was more pronounced the higher the power distance values of the employee. Robert et al. (2000) similarly found a positive association between empowering workers and job satisfaction in the high power distance contexts of Poland and Mexico. In another study, of hotel workers in the autonomous Chinese region of Macau, the authors found that, despite the high level of power distance typically associated with Chinese culture, providing workers with autonomy and discretion in decision-making was associated with higher levels of motivation (Humborstad et al., 2008). Rao and Pearce (2016) documented similar results among those working in the high power distance Indian context: employees of managers who adopted an empowering leadership style reported better collaboration, innovation, and future team performance than employees of managers who adopted a more controlling leadership style.

We also found indications of seemingly culturally incongruent leadership/management styles having positive outcomes among individuals in the US. In an experimental study involving both US and Chinese business students, Chen et al., (2011a) found that leadership behaviors directed at the group-level (rather than any specific individual) had a stronger positive effect on psychological empowerment among the more individualistic US students (relative to the more collectivistic Chinese students). In another experimental study, Erez and Earley (1987) found that US students performed better on the experimental task when directed to set goals as a group instead of being individually assigned a goal.

While the results canvassed above tempt the conclusion that an empowering and/or group-oriented management style is universally effective across cultures, we also encountered evidence of the reverse effect: more control-based leadership styles having positive consequences in seemingly incongruent cultural contexts. In a study of several thousand managers (and their employees) across 50 countries, Hoffman and Shipper (2012) found that employees were more affectively committed to their organizations to the extent their manager demonstrated a control-based leadership style. This finding on its own is surprising given typical prescriptions about what constitutes “effective” leadership (at least in Western contexts), but the authors also found that this effect held irrespective of the power distance of the respondents: control-based leadership styles were positively associated with commitment even in cultural contexts low (as well as moderate and high) in power distance. Such findings obviously counter those presented earlier, but in concert, these results suggest that countercultural leadership/management approaches can produce positive outcomes under certain conditions.

Aside from studies focused directly on management style, we also identified three studies associating positive outcomes with employing foreign (rather than local) management personnel. Interestingly, all of these studies focused on Japanese managers assigned to foreign subsidiaries. Gong (2003) found that assigning Japanese leaders to foreign subsidiaries of Japanese MNEs was associated with higher labor productivity, and, surprisingly, that this effect was stronger to the extent the subsidiary’s host country was culturally distant from Japan, a finding that was virtually replicated in another study of Japanese MNE subsidiaries by Gaur et al. (2007). Consistent with these findings, but focusing specifically on Japanese MNEs with subsidiaries in China, Schotter and Beamish (2011) found that employment of Japanese general managers was positively associated with subsidiary performance, although only among subsidiaries operating in regions of China where levels of foreign direct investment were already high (e.g., Shanghai, Beijing). While acknowledging the different ways these results can be interpreted (consistent with our earlier discussion of Japanese management, perhaps the Japanese personnel were adept at managing in ways consistent with the local culture, or the typical management approach of Japanese has a certain level of universal efficacy), they nevertheless suggest that foreign managers adopting foreign management approaches can, in some cases, have a beneficial impact on the organizations and employees they lead.

Beyond the issue of leadership/management style, we encountered several studies showing certain human resource systems and approaches having positive outcomes that were unexpected or surprising given the cultural context(s) under study. In the aforementioned meta-analysis of 159 studies (covering 29 countries) of the high-performance work systems (HPWS)–business performance relationship, Rabl et al. (2014) followed the standing wisdom of cultural fit in the literature and predicted that HPWS would work better in cultures of low power distance, low collectivism, and high-performance orientation. Yet, they found that HPWS had a positive impact on performance across virtually all the cultures studied, and, even more surprisingly, that this effect was stronger in countries higher in power distance and collectivism. Along similar lines, Jiang et al. (2015) found that implementing human resource practices that encouraged worker participation and transparency of information flows had a stronger positive impact on the performance of subsidiaries of a US-owned MNE to the extent that the subsidiary was operating in a high (not low) power distance culture. Additionally, we found two studies reporting evidence of human resource approaches incorporating elements that would be considered typical of Western companies (e.g., ability-based rather than seniority-based promotion, pay based on individual performance) positively impacting employee attitudes in China (Gamble, 2006; Mayes et al., 2017), and an additional study reporting similar results in Bangladesh (Colakoglu et al., 2016).

While the above studies focus on the outcomes of certain forms of human resource systems writ large, we also found studies documenting positive outcomes of more specific human resource practices. By far the most common subfocus here was pay. The practice of pay-for-performance in particular has frequently been deemed inappropriate for collectivist cultures on account of the individualistic principles it embodies (e.g., Giacobbe-Miller et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2005). Yet, several studies we encountered provide counter evidence. Chang (2006) found that South Korean workers subject to pay-for-performance reported higher levels of work effort. Moreover, when pay-for-performance was used as a part of a broader effort of developing workers, the workers also reported higher levels of organizational commitment. Du and Choi (2010) showed that pay-for-performance was implemented with some success in China, which would seem countercultural for a collectivist culture. They found that pay-for-performance showed a positive impact on employees’ conscientiousness in China. They also observed that pay-for-performance enhances Chinese employees’ affective commitment and helping behaviors when employees are pleased with the performance appraisal system in their firm. In Bloom and Michel’s (2002) results, we also discovered evidence of countercultural pay practices being effective in a Western context: across 460 US companies, they found that firms with more egalitarian managerial compensation (i.e., lower levels of pay dispersion) had better rates of managerial retention, despite the US being an individualistic culture where one would generally expect egalitarianism to backfire.

Two other studies focused on specific human resource practices other than pay. The first is a mixed-methods case study of an MNE’s global rollout of an employee idea suggestion initiative, a typical US approach in which employee voice is valued. In this study, Bonache (1999) found that, despite the program initially being developed and deployed in the MNE’s US operations, it produced positive results (in terms of number of actionable suggestions made) when implemented unchanged in the MNE’s operations in other countries, including those where the exercise of employee voice would typically be seen as incompatible with local cultural norms (e.g., Brazil, Mexico). The second study (Siegel et al., 2019) was based on a large database of companies operating in South Korea. Despite being a cultural context with entrenched gender roles that heavily favor men (particularly in terms of career prospects), the authors found that aggressively hiring and promoting women was positively associated with firms’ productivity and performance.

Finally, we found two studies that spoke to the more general issue of organizational culture and climate. In the first, a study of several thousand employees of an MNE spread across 18 countries, Fisher (2014) presented evidence that a cooperative work climate helped to buffer the negative impact of role overload on organizational commitment irrespective of the level of individualism of the national culture in which the employees work. In the second study involving managers in Peru, where cultural norms generally inhibit employee participation in managerial and strategic decision-making, Parnell (2010) found that managers who viewed their organizations as more participative reported higher levels of organizational commitment than managers who viewed their organizations as less participative. It is worth noting, though, that the reverse relationship was found among the Mexican managers studied, an important reminder of our overarching thesis in this article: under certain conditions, countercultural practices can be effective.

Acceptance of Countercultural Practices

In addition to studies demonstrating the effectiveness of countercultural practices (i.e., in terms of outcomes such as firm performance, or individual motivation), we also identified 18 studies presenting evidence of openness to, and in some cases even endorsement of, countercultural practices by those subjected to them (Table 2).

One of the most frequently documented cases of locals’ preference for countercultural practices is the positive attitudes shown by employees of collectivistic cultural backgrounds (e.g., Chinese, Kenyan) towards individualistic reward arrangements (Chen, 1995; Chiang, 2005; Fadil et al., 2004; He et al., 2004; Lowe et al., 2002; Nyambegera et al., 2000). For instance, Bozionelos and Wang (2007) found that Chinese workers had positive attitudes towards individual performance-based reward systems, and negative attitudes towards equality-based reward systems. This finding countered their prediction that the cultural norms of saving face (‘Mianzi’) and emphasis on personal relationships (‘Guanxi’) would lead to Chinese holding negative attitudes towards reward arrangements based on individual performance. Studies also documented the reverse pattern: individuals from individualistic cultures being receptive to more group-based pay and reward arrangements (Chen, 1995; Chiang & Birtch, 2007, 2012; Lowe et al., 2002). Two other studies showed a preference among Japanese (Lee et al., 2011) and Hong Kong (Chaing & Birtch, 2006) workers for pay based on individual performance rather than seniority-based pay, the latter being a conventional practice in both cultures.

We also encountered studies showing a preference for countercultural leadership/management styles. Selmer (1996), for instance, observed that Hong Kong managers rated the leadership style of managers from the US and UK as most preferable, with managers from Asia surprisingly being rated as having the least preferred leadership style. Such findings align with those of Vo and Hannif’s (2013) qualitative study of Vietnamese MNE employees: despite the high power distance of Vietnamese culture, many employees were found to have favorable attitudes towards the more participatory, less autocratic leadership style that was typical in the US-owned MNEs that they worked for. Mellahi et al. (2010) similarly found that, in the context of the high power distance culture of India, employees responded positively to having more (not fewer) opportunities to exercise voice within their employing organizations.

We also found three studies that suggested a preference for practices that go against their own cultural norms. Varma et al. (2006) found that, despite the typical favoritism towards men in Indian culture (particularly in relation to work and professional matters), Indian employees showed a preference for working with female over male expatriates. Gong (2009) paradoxically found that consumers were more receptive to online shopping, a consumption channel typically viewed as riskier than physical shopping, in countries typically viewed as higher on the cultural dimension of uncertainty avoidance.

Taken together, the studies described above reinforce the findings reported earlier on the efficacy of countercultural practices and reiterate that they cannot simply be discounted as mere anomalies: people and groups do sometimes seem to prefer and desire work-related practices that are not necessarily aligned with, and in some cases even opposed to, the norms and values of their culture. Therefore, these studies, along with those we present in the next section, help to reveal the psychological elements of a causal chain linking countercultural practices to positive outcomes: certain countercultural practices, under certain conditions, can have real and legitimate benefits, not merely because of chance or luck but also because they are perceived favorably and consequently embraced by those subjected to them.

Negative Consequences and Perceptions of Local(ized) Practices

A third category of studies we have identified as relevant did not necessarily show the effectiveness or acceptance of countercultural practices, but revealed that culturally-congruent, normalized, or deliberately localized practices are not necessarily beneficial or perceived positively by locals. We identified 14 such studies in this category, presented in Table 3, which we elaborate below.

The most common variant of this class of studies were those focused on the Chinese practice of guanxi. Despite being a highly embedded aspect of Chinese culture, we encountered several studies in which Chinese employees held ambivalent and sometimes even adverse attitudes towards guanxi. For instance, Chen et al. (2004) found that the use of guanxi as a part of human resource management was negatively associated with Chinese employees’ trust in their managers. Using a mixed-methods approach, Warren et al. (2004) also documented the complex attitudes held by Chinese workers towards guanxi, finding that the perceived benefits and downsides of guanxi vary considerably, depending on other contextual considerations (e.g., the specific nature of the relationship between the connected parties), as well as the standpoint (e.g., manager, organization, community) from which the outcomes of guanxi are evaluated. Chen et al. (2011b) distinguished between interpersonal and group level guanxi, showing that the latter can have a negative impact on employee's procedural justice perceptions. More recently, Yang et al. (2021) observed that guanxi-based HR practices may make Chinese employees emotionally exhausted, and ultimately undermine their job performance. Locals’ negative responses to guanxi-like practices were also observed in other countries beyond China: Chen et al. (2017) reported that Brazilians responded negatively to the Jeitinho practice, a common form of relational favoritism in Brazil, while Boutilier (2009) presented qualitative evidence of Mexican workers holding negative attitudes towards nepotism, which they also perceived to be common in their culture.

The other studies we collected focused on a range of other aspects of local cultures, and revealed the potential downsides of such local(ized) practices and values. In Li et al.'s (2020) experimental study, for instance, it was found that Indian customers evaluated a certain marketing communication less favorably when it incorporated a highly symbolic local cultural artefact (the Ganges river). Azungah et al. (2018) presented qualitative data indicating that the locally prevalent authoritarian leadership style prevented Ghanaian employees from freely discussing their performance with managers. Peng and Tjosvold (2011) found that social face concerns were more salient for Chinese workers in interactions with Chinese as compared to Western managers, which in turn heightened the likelihood of employees acting passive aggressively towards managers. In the U.S., where individual-based performance pay is an established norm, Yanadori and Cui (2013) found that a high level of pay dispersion within R&D teams was negatively related to firm innovation. Prince et al. (2020) similarly found that, contrary to their predictions, the use of bonus payments based on individual performance was associated with higher turnover and worse firm performance among firms operating in cultures with strong performance orientations and high in individualism. Finally, Goby (2015) presents a case study of the many work- and employment-related challenges encountered by workers in the United Arab Emirates arising from the normalized practice of local companies relying on foreign workers.

Related Evidence: The Advantage of Foreignness and the Liability of Localness

An emerging stream of research that provides indirect support for the countercultural practices is the literature on advantages of foreignness, and the related conversation on potential disadvantages of localness. This literature is directly relevant to our investigation, as it also challenges the fundamental field assumption of a need for cultural fit; therefore, we provide here a brief overview of studies related to these topics, indicating links between existing research in IB/IM and the phenomenon of countercultural practices.

The advantage of foreignness has been defined as “intangible social-cognitive perquisites, benefits, and privileges towards foreign organizations via-a-vis indigenous organizations.” (Shi & Hoskisson, 2012: 104). Studies on the advantages of foreignness challenge the traditional IB theme positing that foreignness is a source of liability. For instance, Sethi and Judge (2009) found that American automobile companies enjoyed their “foreignness” in India where local government and customers regarded foreign companies more highly than domestic companies. Un (2011) found that, other things being equal, foreign firms are more likely to achieve better innovation performance than local firms. Taussig (2017) reasoned that foreignness provides multinational companies with the advantage of not being constrained by local norms and networks. This lack of local embeddedness consequently allows foreign companies to make flexible strategic decisions. Edman (2016b) found that foreign financial institutions operating in Japan capitalized on their foreign identity, which allowed them to introduce innovative products and services into local markets. Joardar and Wu (2017) explored the impact of foreignness at the individual level, showing that foreignness of entrepreneurs has a curvilinear relationship with their performance, where both low and very high level of foreignness are associated with higher business performance.

The inversion of the advantage of foreignness is the recently proposed concept of liability of localness: the disadvantages associated with domestic companies that operate only in their own country. Un (2016) found that the localness of a firm undermines its innovation performance. She argued that this is driven by the low level of multiculturalism and the lack of global networks through which new ideas can be generated. Husted et al. (2016) suggested that local firms suffer from the liability of localness as local stakeholders perceive their own domestic firms to be inferior to multinational corporations in terms of product quality, manufacturing systems, and sustainability activities. Perez-Batres and Eden (2008) found that the liability of localness becomes a serious concern in the context of emerging markets where institutional arrangements are rapidly changing. They argued that domestic local firms in emerging markets are disadvantaged compared to foreign companies, because their embeddedness in the old systems of cognitive, normative, and regulatory environments makes it difficult for them to adjust into newly emerged business environments. Extending this view, Jiang and Stening (2013) argue that the liability of localness may have enduring effects even long after institutional change has occurred.

The literature on the advantages of foreignness and the liabilities of localness is consistent with our discussion on countercultural management, in the sense that it challenges the notion that going against established norms necessarily undermines the effectiveness of managers or organizations. Many studies of liability of foreignness were inspired by early versions of neo-institutional theory, which emphasized the benefit of acquiring legitimacy by conforming to three pillars (cognitive, normative, and coercive) of institutional pressure (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). However, institutional theory scholarship has evolved to actively embrace the value of creative deviance, as exemplified in research on institutional entrepreneurship (e.g., Greenwood & Suddaby, 2006) and institutional work (Lawrence et al., 2011). These theoretical developments provide scholars with resources to conceptualize and legitimate the positive outcomes of going against established local norms and practices.

Making Sense of the Evidence on Countercultural Practices

The empirical evidence of countercultural practices we have canvassed above, while supportive of our argument, is rarely accompanied by theoretical explanations purposefully aimed at explaining why and when such practices work. As discussed earlier, the predominant focus on hypothesizing the need for cultural fit and adaptation renders such findings puzzling, inconclusive, and even problematic. As such, the typical explanations offered relate to study limitations, the peculiarity of the research context, and anomalies and outliers. We contend that, by adopting a lens of understanding that allows such findings to be significant, relevant, and legitimate, a variety of explanations can be offered. We have organized these explanations into four categories, each prompting, as we will show later, interesting avenues for future research in global work. These categories are: (1) ontological explanations (i.e., explanations that reside in the nature of the context of global work); (2) epistemological explanations (i.e., explanations related to the way the phenomenon has been understood, or rather, misunderstood); (3) causal explanations (exploring conditions and circumstances that lead to effectiveness of countercultural practices, along with explaining how such effects occur); and (4) functional explanations (referring to the potential purpose and utility of countercultural practices). We detail these categories below, along with providing a summary in Figure 2.

Ontological Explanations

Clearly, the investigation into why countercultural practices might be effective must begin with exploring the context of global work, and, in particular, the main protagonist in this story: culture. It is important to note that, in the context of research related to the relevance of culture to IB/IM, the focus is largely on the home-country culture, with limited understanding and consideration of local cultural features. Most models of local adaptation consider the host-country culture in terms of its “distance” from the home culture (Shenkar, 2001). As noted above, theory (and the practice that followed it) often depicts the host culture as homogeneous, well-defined, and consistent (Tung, 2008). Several major theoretical advancements in the study of culture demonstrate that such a view is inaccurate (e.g., Caprar et al., 2015), and offer explanations with regard to why countercultural approaches might sometimes be appropriate. The first development we bring to attention is the concept of tightness–looseness of cultures, associated with cultural change. The second important development is the distinction between desired cultural values and actual practices. Finally, the way culture is conceptualized in general is also relevant to our discussion. These well-documented culture-related phenomena have direct implications for understanding why countercultural practices are sometimes effective.

Cultural strength, cultural change, and acculturation

The concept of tightness–looseness has been long discussed in the study of culture as the strength of social norms and the degree of sanctioning within societies (e.g., Berry, 1967; Pelto, 1968; Triandis, 1989), yet its application is largely missing in the study of global work. The concept was brought back to attention by Gelfand et al. (2006), who proposed that the tightness–looseness dimension has implications both at the individual and organizational levels, influencing the amount of intra-cultural variance, and, implicitly, the variability across organizations. In terms of adapting business practices to local cultures, it is fair to expect that not only cultural distance but also the tightness–looseness of the host culture is important: a loose culture means norms are less clearly defined, and therefore difficult to identify, and when they can be identified, the level of “compliance” to such norms is limited, allowing for greater variability in terms of what is accepted and/or expected. Thus, in loose host cultures, the concern for cultural fit is less important.

Finally, cultures – especially loose ones – are likely to be experiencing a process of change. A range of factors has led to the development of a global culture that progressively impacts all corners of the world (Arnould, 2011; Ritzer, 2018). And this change can be manifested both at the societal and individual level, with many individuals becoming multicultural because of global mobility and globalization in general. That is, individuals can internalize more than one culture (Brannen & Thomas, 2010); as a result, different cultures can coexist both at the societal and individual level, and influence perspectives and preferences in multiple ways (Lücke et al., 2014; Maddux et al., 2021). Defining cultural sensitivity against traditional values measured at the country level that may, or may not, be reflected in the employees’ cultural profile defies its very purpose: modernized members of the culture might welcome non-local approaches (e.g., Caprar, 2011), and, indeed, perceive the use of localized (i.e., traditional) practices as outdated or unhelpful. All cultures are exposed to changing factors, but loose cultures are more likely to incorporate practices that are considered legitimate and/or efficient based on other external criteria, such as legitimacy or efficiency, as established in other cultures or at a global level. On the contrary, in tight cultures, the traditional model of localization may still be valid, as these cultures have clear norms that are highly sanctioned, thus inhibiting the degree to which such cultures welcome culturally unusual practices.

Desired cultural values and actual practices

As with any social construct, our understanding of what culture means is constantly evolving. Recently, several conceptualizations have helped to enhance our understanding of culture and its various features. In management studies, Hofstede’s (2001) notion of the cultural onion (placing values at the core of culture, and practices as a manifestation of values) gained a lot of popularity and generated extensive research focused on identifying major dimensions describing a culture. This assumption of a perfect relationship between cultural values and practices was challenged by the GLOBE study (House et al., 2004), where values and practices were measured separately, based on the observation that “what is” in any given culture does not necessarily match “what should be”. In fact, even Hofstede and his collaborators mentioned such a distinction in their study, given the fact that value items and practice items loaded on different factors, a distinction they recognized to be “present not only in the conception of the researchers, but also in the minds of the respondents” (1990: 295). While there is still debate regarding the advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches to measuring culture based on the above conceptualizations (e.g., Hofstede, 2006; Javidan et al., 2006; Smith, 2006), the data revealed by the GLOBE study indicate that there is a gap between “is now” societal culture scores and “should be” scores on certain dimensions. For instance, a study of leadership prototypes in the Middle East and North Africa using the GLOBE dimensions revealed that different values were reflected in the practice of leadership, and the preference for leadership in these countries (Kabasakal et al., 2012). Such findings also reflect the identity-related notion that people not only form perceptions of who they are at present but also ideal possible selves that detail who they wish to become in the future (Markus & Nurius, 1986). This dualistic perspective of culture might explain why certain cultures are more open than others to taking on new business practice that appears to be countercultural (when considered against the “is now” measures): if the complexity of culture is properly considered, such countercultural practices might in fact be consistent with the desired aspect of a given culture, and therefore welcomed by its members.

Beyond equating culture with nation

It is widely accepted that distinct cultures can emerge at virtually any level of human organization, from nations down to families and intimate friend groups. Closely related to the significant evolution on conceptualizing culture in IB/IM, beyond defining it using national borders (e.g., Au, 1999; Caprar et al., 2015; Taras et al., 2016; Tung, 2008; Tung & Stahl, 2018), it may be the case that certain practices that seem “countercultural” at a national level are, in fact, culturally congruent at subnational or cross-national levels (e.g., in terms of the culture of certain regions, communities, or organizations). For instance, researchers have begun to acknowledge the unique characteristics of global cities, defined as cosmopolitan environments (e.g., Goerzen et al., 2013), and have called for moving away from traditional mean-based measures of cultural distance towards an approach which accounts for within-country cultural variation (e.g., Beugelsdijk et al., 2015). Yet, most of the studies we identified through our review focused on national culture and did not consider or control for potential “glocal” cultural effects (see Gould & Grein, 2009), intra-country ethno-linguistic fractionalization (see Luiz, 2015), or the existence of transnational and subnational archetypes (Venaik & Midgley, 2015).

The focus on national culture in research studies would be less problematic if such studies employed samples that were truly representative of a country’s population (and thus its culture), but the inherent limitations of scholarly research (e.g., gaining access to data, resource constraints) mean that population-level samples are rarely the case. Rather, researchers usually make use of samples of firms or individuals from specific geographic areas, occupations, industries, organizations, and communities, all of which constitute subnational collectives that can have subcultures that differ from the culture of the country “as a whole”. Moreover, measurements and methodology that do not consider the large variability in cultural values and practices (deviation from the mean) within the population studied (Beugelsdijk et al., 2015), and a restricted range of methodologies (Nielsen et al., 2020), further limit the accuracy of understanding the relationship between business practices stemming from a home culture and the host/local culture. The MNE subsidiaries can themselves represent subcultures that challenge traditional geographical perspective on defining cultures (e.g., Caprar, 2011; Goerzen et al., 2013). In this way, practices that are in fact a good fit with a particular (sub)culture are incorrectly cast as “countercultural”, a label rendered by researchers’ overly blunt assumptions about the default culture of their study’s participants, rather than any mismatch between the culture and the practice in question.

Epistemological Explanations

The historical account on the development of the cultural fit thesis offered earlier suggests that it was not its unquestionable validity that made it so central to IB/IM. Rather, the exaggerated focus on cultural fit seems to be better described as a typical case of “more of the same” principle of problem formation (Watzlawick et al., 1974). In the initial stages of globalization, the typical approach was, indeed, culturally insensitive (as noted in our review): the companies may have been ignorant regarding the existence of significant cultural differences, or, if they recognized such differences, probably did not recognize their relevance to business. Furthermore, historical, political, and economic reasons might have supported an ethnocentric view on the part of Western companies, and on the part of Western academics. Such views – clearly expressed at the time, as we saw in our review – needed correction, and, naturally, the culturalist (or the culture-specificity) view developed. However, if the extreme of convergence (or culture-free approach to business) was biased, so was the corrective action of “fit”, especially when “fit” became a “more of the same” principle (an exaggerated emphasis on what has been ignored before), leading to ignorance of other aspects (i.e., “contexts”, as mentioned in some of the articles reviewed). In other words, the same exclusivity in focus that caused the initial problem also plagued the proposed solution. The obsession with demonstrating the importance of cultural fit (also fueled by an ideological stance expressed in the morality of cultural sensitivity) precluded some researchers from acknowledging that cultural fit is not always helpful.

In addition, due to a quest for parsimony and generalizability (Poole & Van de Ven, 1989), academic theories tend to oversimplify realities characterized by complexity and variation (Glynn et al., 2000). In tracing the development of the cultural fit thesis, we note that the debate between localization and standardization stems from a dichotomous logic, in which alternatives are seen as mutually exclusive (i.e., it is either standardization or localization, not both). However, as suggested by Ralston et al.’s (1993) findings, such absolutist views do not accurately describe the reality: evidence for both convergence and divergence has been found, prompting the development of the newly coined concept, “crossvergence”. It is still rather difficult to explain why this concept has not influenced thinking in the field to a greater extent; for instance, the Pudelko and Harzing (2007) study did not even mention it in their otherwise very meticulous review of the convergence/divergence debate. Perhaps one of the reasons is the complexity of the concept and the need to further explain its meaning (Witt, 2008). It is also possible that limitations emphasized by Tung (2008), who drew attention to the fallacious assumptions of cultural homogeneity and cultural stability over time (problems specific to most cross-cultural studies, in fact), also limited the theoretical appeal and applicability of the concept. In other words, there were conjectural factors that facilitated the development of a unilateral view (that of cultural fit), while hindering the recognition of possible and valuable alternative solutions. As Lewis (2000) noted – based on initial ideas formulated by Cameron and Quinn (1988) – there is a need for new perspectives in addressing the complex problems specific to the field, especially recognition of the paradoxical nature of certain phenomena. The topic explored here would undoubtedly benefit greatly from such new perspectives.