Abstract

The Welch et al. (J Int Bus Stud 42(5):740–762, 2011) JIBS Decade Award-winning article highlights the importance of the contextualization of international business research that is based on qualitative research methods. In this commentary, we build on their foundation and develop further the role of contextualization, in terms of the international business phenomena under study, contemporaneous conversations about qualitative research methods, and the situatedness of individual papers within the broader research process. Our remarks are largely targeted to authors submitting international business papers based on qualitative research, and to the gatekeepers – editors and reviewers – assessing them, and we provide some guidance with respect to these three dimensions of context.

Résumé

L’article de Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki et Paavilainen-Mäntymäki’s (2011) - lauréat du JIBS Decade Award - met en lumière l’importance de la contextualisation dans la recherche en affaires internationales basée sur les méthodes qualitatives. Dans ce commentaire, nous nous appuyons sur leur fondement et développons davantage le rôle de la contextualisation, plus spécifiquement, les trois dimensions du contexte, à savoir le contexte du phénomène d’affaires internationales à l’étude, le contexte des conversations contemporaines sur les méthodes de recherche qualitative, et la contextualisation des papiers particuliers dans le processus de recherche plus large. La cible principale de nos remarques est double : d’abord, elles s’adressent aux auteurs qui soumettent les articles portés sur les affaires internationales et basés sur la recherche qualitative ; ensuite, elles sont aussi destinées aux gardiens - éditeurs et évaluateurs - en charge de les évaluer. Nous apportons également quelques orientations liées à ces trois dimensions du contexte.

Resumen

El artículo ganador del premio de la Década de JIBS de Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki y Paavilainen-Mäntymäki (2011) resalta la importancia de la contextualización de la investigación en negocios internacionales que se basa en métodos de investigación cualitativos. En este comentario, nos basamos en sus fundamentos y desarrollamos aún más el papel de la contextualización, en términos de los fenómenos de negocios internacionales que se estudian, las conversaciones contemporáneas sobre los métodos de investigación cualitativa y donde se sitúan los artículos individuales en el proceso de investigación más amplio. Nuestras aportaciones se dirigen en gran medida a los autores que presentan trabajos sobre negocios internacionales basados en investigación cualitativa, y a los controladores de acceso (editores y evaluadores) en la evaluación de estos, y damos algunas orientaciones con respecto a estas tres dimensiones del contexto.

Resumo

O artigo vencedor do JIBS Decade Award de Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki (2011) destaca a importância da contextualização da pesquisa de negócios internacionais que se baseia em métodos qualitativos de pesquisa. Neste comentário, desenvolvemos a partir de sua base e desenvolvemos ainda mais o papel da contextualização, em termos dos fenômenos de negócios internacionais em estudo, conversas contemporâneas sobre métodos de pesquisa qualitativa e a situação de artigos individuais dentro do processo de pesquisa mais amplo. Nossos comentários são amplamente direcionados a autores que enviam artigos de negócios internacionais com base em pesquisa qualitativa e aos gatekeepers - editores e revisores - que os avaliam, e fornecemos algumas orientações com relação a essas três dimensões de contexto.

摘要

Welch、Piekkari、Plakoyiannaki 和 Paavilainen-Mäntymäki (2011 年) 的JIBS 十年获奖文章强调了基于定性研究方法的国际商务研究情境化的重要性。在这篇评论中, 我们就所研究的国际商务现象、定性研究方法的同期对话和更广泛的研究过程中个别论文的定位, 在他们的基础上进一步开发了情境化的作用。我们的评论主要针对的是提交基于定性研究的国际商务论文的作者和对这些论文进行评估的看门人——编辑和审稿人, 我们就情境的这三个维度提供了指导。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

More than a decade ago, Catherine Welch, Rebecca Piekkari, Emmanuella Plakoyiannaki and Eriikka Paavilainen-Mäntymäki looked over the landscape of qualitative international business (IB) research and found it wanting. They believed there was a dearth of choices in methodological approaches to qualitative research, which led to limited diversity in methods and, more seriously, to a paucity of theoretical insights being generated. As a response, they developed a typology of approaches to case study research and published it in the article “Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research” (Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki, & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, 2011). This article (hereafter referred to as WPPP) has received the 2021 JIBS Decade Award, and we are honored to be invited to write a commentary on it ten years after it was published.

The Decade Award recognizes the most influential paper published in JIBS in a given year, and the selection committee articulated three main reasons for the influence of WPPP. It has been highly and widely cited. It initiated a much-needed discussion about making and articulating explicit and consistent methods-related choices that raised the quality expectations of authors and reviewers. And it emphasized the importance of contextualization in IB theory developed through qualitative research, which is what we focus on in this commentary. These are important and impactful outcomes to celebrate.

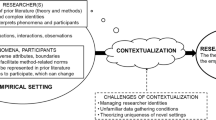

In this commentary we extend their discussion by highlighting three aspects of the contextualization of IB research. First, we examine the contextualization of the international business phenomena under study. Second, we consider the context in which papers are written, in terms of contemporaneous conversations about qualitative research methods. Third, we discuss the situatedness of individual papers within the broader research process. Our remarks are largely targeted to authors submitting IB papers based on qualitative research, and to the gatekeepers – editors and reviewers – assessing them, and we provide some guidance with respect to these three dimensions of context. Before our discussion of context, however, we first make some preliminary remarks on the WPPP typology.

THE TYPOLOGY

Despite the importance of WPPP, we disagree with some aspects of it, as is a normal part of scholarly discussions. In particular, we have some reservations about the typology itself. We believe that it mischaracterizes certain case-oriented research methods, particularly those associated with Eisenhardt (1989) and Yin (2009); for a more recent discussion of case methods, see Eisenhardt (2020, 2021) and Gehman, Glaser, Eisenhardt, Gioia, Langley, and Corley (2018). We are also confused by WPPP’s notions of the transferability of findings based on qualitative methods because the distinctions they make do not seem to be mutually exclusive. For example, “generalization to population” (associated with inductive theory building), “generalization to theory” (associated with natural experiments), and “contingent and limited generalization” (associated with contextualized explanations) (Welch et al., 2011: 745) seem simultaneously true of much qualitative research because the relevant population and extant literature are bounded. Finally, even though WPPP state that they aim to increase research plurality rather than to advocate for a particular approach, it is difficult not to see the WPPP typology (as depicted on p. 750) as a normative framework when one quadrant is labeled “weak, weak” and another quadrant is labeled “strong, strong” on qualities argued to be good. We find it particularly difficult to understand the denigration of induction, given that qualitative research is widely seen to be based on both inductive and abductive reasoning; see a discussion of this in two disciplines important to IB, management (Grodal, Anteby, & Holm, 2020; Harley & Cornelissen, 2020; Van Maanen, Sørensen, & Mitchell, 2007) and marketing (Dolbec, Fischer, & Canniford, 2021).

Given these misgivings, when we started to write this commentary, we sought to understand how the WPPP typology has been used in subsequent IB scholarship. It is not possible to assess whether WPPP has increased IB research plurality, because a “before” base rate does not exist. Instead, we followed the approach used by Lerman, Mmbaga, and Smith (2020) who studied how the ideas in Langley’s (1999) article on process data analysis were applied in subsequent research, and examined how WPPP ideas were applied in the JIBS articles that cite it. We found that while a few authors correctly classify their research according to the WPPP typology, more do so incorrectly or inconsistently, and some authors reference the article incorrectly. For example, some suggest that it recommends building theory inductively, which it does not. However, the majority of papers reference WPPP with what Lerman et al (2020) refer to as a “cursory nod.” These cursory nods are general statements, such as assertions that case studies are dominant in qualitative IB research or that case studies are well suited for theory development. The high rate of cursory nods seems characteristic of highly cited articles in general (see Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019; Lerman et al., 2020). More specifically, given the paucity of authoritative references on qualitative methods in IB in 2011, we believe that cursory nods to WPPP played an important role in legitimating qualitative research in general, and case studies in particular, when authors submitted an article or when reviewers requested methods-related justification. Thus, we do not view cursory nods negatively. Rather, we see them as pointing to claims that need to be legitimated. We return to this point later in the commentary. From this investigation, we found that the most references to WPPP relate to the contextualization of IB theory, which supported our interest in this aspect of the article. It is to this that we now turn.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT IN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS RESEARCH

WPPP note that contextualization of theory is particularly important in IB research given the diversity of national contexts (Welch et al., 2011: 741). It is therefore unsurprising that papers embracing the contextualization of IB phenomena have been influential in the field. To illustrate this influence, Table 1 lists the last ten Decade Award-winning articles in JIBS. It is evident from their titles that most of the articles are explicitly context-oriented and even a quick reading of the remaining papers reveals strong contextual undertones. Collectively, these award-winning papers span context conceptualized as: culture (Kirkman, Lowe, & Gibson, 2006; Shenkar, 2001; Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen, 2010); business networks (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009); institutions (Brouthers, 2002; Jackson & Deeg, 2008; Meyer & Peng, 2005); countries (Buckley, Clegg, Cross, Liu, Voss, & Zheng, 2007; Minbaeva, Fitzsimmons, & Brewster, 2003); and industries (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004). Table 1 also provides an excerpt from a commentary written about each award-wining article. These excerpts show that when scholars discussed the articles a decade after they had been published, they were calling for even greater scope and/or depth of contextualization. Context is not the only notion discussed in these articles and commentaries, of course, but it is invariably an important part of the discussion.

These Decade Award-winning articles are either conceptual or based on quantitative data, and the primary emphasis is on contextual differences; specifically, the papers focus on how and why outcomes vary across contexts. The articles are consistent with the assertion that “exploring the contingency effects of contextual differences on specific relations is central to the field of IB” (Beugelsdijk, Kostova, & Roth, 2017: 38). WPPP suggest that context can play a broader role in qualitative IB research methods and we agree. In the paragraphs that follow, we attempt to advance this agenda by examining the concept of context more closely. Guidelines relevant to the three aspects of context discussed in this commentary are shown in Table 2.

THE CONTEXT OF THE INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS PHENOMENA BEING STUDIED

A distinction we find useful is the difference between a paper’s empirical context and the theoretical concepts it can reveal. A case can be an empirical unit (e.g., the European sales division of a large multinational company) and also an instance of a theoretical category (e.g., an instance of subsidiary role evolution), to draw on Balogun, Jarzabkowski, and Vaara (2011) as an example. Cases as empirical units exist independently and are “found,” while researchers construct or “make” the claim that empirical cases can be used to learn (more) about certain theoretical constructs (see Ragin, 1992). Categorization therefore underlies the coupling of the empirical case and the theoretical construct (Cornelissen, Höllerer, & Seidl, 2021; Grodal et al., 2020). The value of an empirical case as an instance of a theoretical category is based on how it expands understandings of the theoretical conversation about the focal category (Walton, 1992). Keeping in mind this distinction between an empirical case context and theoretical constructs that can be abstracted from the empirical case can help authors in crafting contextualized papers and reviewers in assessing them.

Selecting Research Sites as Empirical Contexts

As WPPP assert, authors need to embed the theoretical explanations offered in a paper in the study’s empirical context. Thus, the selection of research sites is the bedrock on which the theoretical explanation rests, and we’re surprised that WPPP does not discuss this issue. Specific research sites and informants should be selected to ensure that the focal phenomenon can be observed in a manner which facilitates theoretic insights. Various approaches to doing this can be observed in papers published in JIBS.

One approach prioritizes contextual contingencies and attention to variance. The researcher can “bake” variance into the selection of empirical cases, in order to be able to explain the effects of different contextual conditions on outcomes. For example, Geary and Aguzzoli (2016) varied the institutional and organizational conditions of subsidiaries within a single Brazilian multinational enterprise (MNE) (the empirical context) and explained variation in HRM practices by the power relations and institutional change they faced (the theoretical matter of interest).

A second approach prioritizes theoretical or literal replication (Yin, 2009: 54) rather than variance. The researcher can identify the gap in the conversation related to the theoretical construct in the literature and select a set of research sites (empirical cases) where the theoretical phenomenon is most likely to be observed. Multiple cases are selected to achieve theoretical saturation: the point at which the analytical categories of the phenomenon are well specified and further data gathering is unlikely to yield little new to the conceptualizations (Corbin & Strauss, 2008: 263). For example, Monaghan and Tippmann (2018) selected MNEs selling software (the empirical context) to explain how companies multinationalize rapidly due to pressures for early market domination (the theoretical matter of interest).

A third approach prioritizes confrontation with existing theory. The researcher can select an empirical case that is known a priori to be at odds with current theoretical explanations (see Siggelkow, 2007). Jonsson and Foss (2011) followed this approach when they studied the retailer IKEA (the empirical context). While then-current theory on replication strategy emphasized the cost of deviating from precise replication (Winter & Szulanski, 2001), IKEA was known to be successful in combining replication with increasing local adaptation (the theoretical matter of interest). The purpose of the research was to extend existing theory on replication strategy by explaining how the company was able to do so.

This discussion shows that there are multiple ways for qualitative researchers to select empirical cases to develop explanations for new theoretical categories. At a fundamental level they should recognize the difference between an empirical context and the theoretical constructs that it may be an instance of, and the importance of selecting empirical cases based on theoretical considerations. Authors need a strong grounding in prior literature to do this well, to ensure that they are attuned to the theoretical implications of different empirical contextual features and recognize that some empirical contexts are likely to be richer in this respect than others. In papers undergoing review, authors should provide, and gatekeepers should insist on, an explanation of the theoretical constructs that are focal, and how they justify the selection of empirical research sites and informants. And once the empirical findings have been presented, authors should provide an explanation in the other direction, from the empirical context to the theoretical constructs, to show how their study has changed our collective understanding of the focal theoretical conversation.

Selecting Analytical Boundaries to Define Theoretical Constructs

Qualitative IB researchers have discretion over how they embed the empirical context in the theoretical explanations they provide through their research, but regardless of the approach they use, they can use only a small proportion of the empirical contextual conditions characterizing research sites and informants. Askegaard and Linnet (2011) point out that any particular empirical context is multidimensional, involving culture, nationality, geography, history, temporality, materiality, and so on. And Johns (2006) illustrates that the manifestation of a particular contextual feature can vary by salience and impact. Thus, any empirical research setting is characterized by a myriad of contextual features. In order to avoid particularism, where cases are incomparable because they are contextually unique, an analytical decision for authors is to select which of the contextual conditions characterizing the setting is relevant to the theoretical story they are telling in their paper (Askegaard & Linnet, 2011). In embedding their empirical study in a particular theoretical conversation, they are disconnecting it from other theoretical conversations, thereby articulating the basis on which their findings can be compared with those of other studies.

This suggests that delineating the boundary conditions (Busse, Kach, & Wagner, 2017) of the explanations provided by their study is an important task for authors, as WPPP assert. Tenzer, Pudelko, and Harzing (2014) provide an illustration of such delineation. To focus on variance in the theoretical phenomenon of interest (trust formation in multinational teams), they kept home country and industry constant. The authors recognized that the boundedness of the empirical context might constrain the transferability of their theoretical insights to other empirical contexts. Accordingly, they cautioned that “our findings are specific to our case companies of the Germany automotive industry, and care needs to be taken when transferring them to MNTs [multinational teams] in other corporations, home countries and industries” (Tenzer et al., 2014: 530). Failure to specify boundary conditions may lead to misleading foundations for future research. For example, a decade after their study on knowledge transfers in international acquisitions was published, Birkinshaw, Bresman, and Nobel (2010: 24) observed that the Swedish MNEs they studied were different than other MNEs and so their study “ended up putting forth a very ‘Swedish’ view of the world” that might not be reflected in a study of American or Japanese MNEs. Here the empirical context of the paper remains stable over time, but the authors have reinterpreted the theoretical transferability of the study with the passage of time.

THE CONTEXT OF CONVERSATIONS ABOUT QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

When authors write empirical papers, they often rely on authoritative methods-related references to justify their choices. This suggests that a second facet of context relevant to the plural ways in which qualitative IB researchers can theorize is the evolution of understandings about what constitutes good practice, or even “best practice.” Eisenhardt (2021) reminds us that methods-related discussions are always embedded in an institutional context, and that what is considered appropriate or advisable when it comes to gathering, analyzing, and writing up findings changes over time, and may be specific to certain fields (such as IB) or journals (such as JIBS) at a particular point in time.

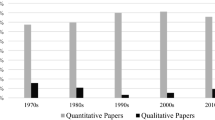

To put WPPP into its institutional context then, it is important to consider what methodological conversations and controversies about the conduct of qualitative research were current when WPPP was published in 2011. At that time, papers based on qualitative research in general, and qualitative case study research in particular, were increasingly being published in the broader field of management with which IB intersects; indeed, in the decade between 2000 and 2010, there were as many qualitative papers published in management journals as in the prior two decades combined (Bluhm, Harman, Lee, & Mitchell, 2011). Moreover, qualitative research was being recognized for the caliber of its contributions, with papers reliant on qualitative methods frequently being rated as offering the most novel and counter-intuitive theories (e.g., Bartunek, Rynes, & Ireland, 2006).

Within the field of IB at the time WPPP was published, then, qualitative research was in the process of gaining legitimacy, and it was becoming more likely that it would be published in JIBS. Yet barriers to publishing qualitative research persist, at least in part because reviewers have difficulty assessing the quality of this type of work (Pratt, 2009). And it seems that within the field of IB, authors who choose to conduct qualitative research are sometimes compelled to justify having done so. For example, the introduction to the methods section in Jonsson & Foss (2011) (which appeared in the same special issue as WPPP) begins with a defense of “small-N research designs” (by which they appear to mean any kind of qualitative research based on a small number of case studies). In part, it reads as follows:

Small-N research designs are often regarded as somewhat suspect, as heavy sample bias implies problems of external validity …. However, a basic lack of knowledge about which variables matter, how they are causally related, etc., often warrants small-N samples … [A]s Dyer and Wilkins (1991: 617) explain, if executed well, case studies can be extremely powerful [when] authors have described general phenomenon so well that others have little difficulty seeing the same phenomenon in their own experience and research ….. Such [well-executed cases] are successful in terms of identifying generative mechanisms that other researchers can recognize in the cases they investigate (Jonsson & Foss, 2011: 1083–1084).

Regardless of whether these lines were included in the original submission or whether the authors added them during the review process, they appear to suggest that, at that time, qualitative research struggled for acceptance, and was still regarded by some as “somewhat suspect.”

In their prevailing institutional context, then, it is not surprising that WPPP sought to systematize the craft of conducting qualitative research in general, and case studies in particular. Their efforts to delineate terminology and differentiate among types of case studies can be seen as offering guidance to qualitative researchers to help them improve their chances of conducting high quality work and ultimately navigating the review process successfully. This same goal can be discerned in work published in the broader field of management, both prior to and during the same time period, that offered “templates” (Langley & Abdallah, 2011) for conducting different kinds of qualitative research. Chief among these were Eisenhardt’s (1989) articulation of the multiple case study method, Langley’s tutorial on process theorizing (1999), and Gioia’s grounded theory inspired approach to data analysis (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, 2013). Though it was not necessarily the explicit intent of these authors (see Gehman et al., 2018), each of these templates offered aspiring qualitative researchers advice on how to craft a contribution that would not only be theoretically novel, but that would also be regarded as conforming to a credible genre of qualitative research by reviewers at a time when “boilerplates” (Pratt, 2009) were in scarce supply.

These reflections on the institutional context a decade ago raise questions about emerging aspects of the institutional context for qualitative research in international business today. Two striking trends are worth noting, given our goal of helping authors who seek to publish qualitative work, and gatekeepers who handle qualitative submissions to IB journals. The first of these trends, perhaps paradoxically, is a turn against templates of the type that have become popularized. Although templates have helped to de-mystify the qualitative research process for scholars and offer some methodological coherence, leading figures among the qualitative methods cognoscenti have begun to advocate moving away from the use of methodological templates both in conducting, and reporting on the conduct of, qualitative research (e.g., Corley, Bansal, & Yu, 2021: Eisenhardt, 2021; Eisenhardt, Graebner, & Sonenshein, 2016; Harley & Cornelissen, 2020; Pratt, Sonenshein, & Feldman, 2020b; Reay, Zafar, Monteiro, & Glaser, 2019).

There are multiple reasons for this “anti-template” turn. Seasoned qualitative researchers are observing that templates encourage formulaic, oversimplified approaches to conducting and reporting on the conduct of qualitative research that often violate the very spirit in which the original templates were proposed (e.g., Eisenhardt et al., 2016; Harley & Cornelissen, 2020; Pratt et al., 2020b). This arises in part because novice qualitative researchers fail to realize that templates cannot and should not fully specify how data collection or analysis should be undertaken. Moreover, close adherence to templates can restrict the methodological approaches to a much narrower set than is ideal, and may inhibit researchers from using appropriate, if less common, forms of qualitative data analysis (for example, narrative analysis, Pratt et al., 2020b). And templates can stifle novelty and creativity both in the approach to analyzing data, and in the theories that result (Corley et al., 2021). While these template-based approaches may reassure (some) reviewers that qualitative research has been done rigorously, leading methodologists reject this view, and argue that the standardization associated with templates must be resisted lest “rigor” give way to “rigor mortis” (Eisenhardt et al., 2016) and excessive conformity result in dull and uninspiring scholarship (Harley & Cornelissen, 2020; Reay et al, 2019).

The second trend of note is a decoupling of calls for transparency from those for replicability in qualitative research (e.g., Monroe, 2018; Pratt, Kaplan, & Whittington, 2020a). The “replication crisis” in experimental psychology has led some to suggest that in order for qualitative research to be transparent, it needs be replicable. This argument is flawed, however, on ontological, epistemological, and ethical grounds.

Ontologically, the notion that research should be replicable assumes that reality is static and unchanging. However, most qualitative research is anchored in an assumption that reality is not fixed and unchanging but rather is continuously changing and contextually contingent in complex ways. Epistemologically, the notion that research procedures can be fully determined in advance based on a priori hypotheses, while often applicable to experimental research, is inapplicable for qualitative research; qualitative research is not based on deductively testing hypotheses but is typically guided by a mixture of induction and abduction, which can only be realized if qualitative researchers are open to amending their research procedures based on insights they glean during data collection and analysis (Pratt et al., 2020a, 2020b). This is why pre-registration of studies is inappropriate for qualitative work (Pham & Oh, 2021). Ethically, certain procedures advocated for ensuring the replicability of experimental research can be inappropriate for qualitative research. In particular, calls that suggest that replicability will only be possible with full transparency in the form of public sharing of data fail to recognize that much qualitative data cannot be de-identified, and that it would therefore be unethical to store such data in public repositories (Monroe, 2018). Interview transcripts are difficult if not impossible to strip of all identifying information, and the same is often true of field notes. As Pratt et al. (2020a: 8) note, most ethics review boards would deem it inappropriate to share interviews in a publicly accessible archive because “doing so could allow members of the public, including those in power over the interviewee, to know the identity of the interviewee.”

Arguments against applying a replicability logic to qualitative research have gained such traction that a recent JIBS editorial declares: “Replication as a quality-related criterion is especially relevant for quantitative research, but rarely applicable to qualitative research …. For qualitative research, the rich reporting of evidence inside the article can assist the reader in verifying quality” (Beugelsdijk, van Witteloostuijn, & Meyer, 2020). As this statement suggests, the current consensus is that one of the best means of ensuring transparency in qualitative research is to include ample data within articles to support whatever theoretical claims are made (e.g., Jarzabkowski, Langley, & Nigam, 2021). Qualitative researchers also concur that transparency is aided by clearly describing and explaining the rationale behind methodological choices as they evolve over the course of a research project (e.g., Pratt et al., 2020b).

Taking into account the evolving institutional context facing qualitative IB researchers, it appears that – relative to the era when WPPP was published – there may be less need for authors to justify the very use of qualitative data. What they will need to be ever-more concerned with is explaining with clarity and detail the data they have collected and the specific approaches they have used in analyzing it. While the familiar templates are likely to serve some researchers’ purposes, authors will want to ensure that they are not adopting them automatically or inappropriately. And they will need to be transparent in revealing and justifying the choices that have guided the research process.

Gatekeepers, for their part, will need to be ever mindful that qualitative research crosses ontological boundaries (Eisenhardt, 2020; Pratt et al., 2020a) and should encourage methodological creativity rather than insisting on template conformity (Corley et al., 2021). At the same time, we believe gatekeepers should not automatically censor or discourage work that deploys familiar templates; let us not swing the anti-template pendulum that far! We would also encourage gatekeepers to refrain from policing some practices in favor of others. Although the WPPP typology may have led some to regard induction as a weak route to developing causal explanations that are well contextualized, there is no consensus on this view. We therefore encourage gatekeepers to recognize that researchers are bricoleurs whose approaches to developing theories should and will vary (see Denzin & Lincoln, 2000; Pratt et al., 2020b). Focusing on the quality of the insights developed, rather than on rigid rules or favored practices for developing theory, should only enhance the caliber of the contributions made by qualitative IB scholars.

THE CONTEXT OF THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Yet another way in which the notion of context applies to qualitative IB research relates to the contextualization of a particular paper within the research process. Often qualitative research endeavors are sprawling in nature: they are typically conducted over multiple years; they frequently involve multiple collaborators located in different regions or countries; those collaborators are normally engaged in other projects at the same time; and they are undergoing personal transitions (having children, losing parents) as well as professional ones (becoming tenured, taking on administrative posts, or moving from one university to another). In our experience, it is not unusual for research projects to span much of a decade once the phenomenon of interest has been identified, taking into account applying for funding, selecting the data to be collected, gathering and analyzing it, producing manuscripts and going through review processes.

Specific papers associated with a project also have peripatetic journeys. They might begin life as a conference submission or invited research presentation, be revised based on feedback, targeted to a specific journal, revised based on reviewer feedback, accepted at the original journal or redirected to a new journal following rejection, and eventually find a home after many rounds of reviewer feedback and revision. The time span from original submission to final acceptance of a qualitative research paper obviously varies greatly, but in our experience, it is rare for this process to conclude in less than a two-year period and it frequently takes longer than three.

Contextually, how does all this matter? First, consider how the contexts for research projects change over their life spans. For example, over the course of a multi-year data collection exercise, some of the very characteristics of the empirical context that drove the choice of cases (see our first point above) can evolve or be abruptly disrupted. And while this may create an opportunity for studying process or disruption, it means that the rationale for original choices may no longer hold. Another contextual factor that can change is the availability of data sources: key informants can change jobs, pass away, or simply change their mind about cooperating. Archival data sources such as speciality blogs or news aggregators can cease publication. Firms can go out of business, be purchased, or be jolted by unforeseeable external shocks, such as pandemics. Of course, the skilled qualitative researcher learns to pivot and adapt, but this may mean that the originally intended scope and goals of the project cease to be viable, and that new ones must be identified.

Yet another “moving part” in the contextual field of a given project is the theoretical conversation (or conversations) which the project is intended to join, extend, or revolutionize. Those conversations rarely stand still. And as new papers are published by other research teams that advance the targeted conversation, contributions originally envisioned at the outset of a project can be eclipsed or rendered incremental.

Researchers themselves are moving parts and can change over the course of a project. For example, over time different aspects of the data may capture their attention, and new collaborators may bring new interpretations. With so much in motion, the original design choices in any given project are rarely intact by the project’s conclusion.

Next, consider the context associated with particular papers. In the course of their journey through a review process (or processes), qualitative research papers often change dramatically owing to repeated rounds of review team feedback. Given the evolving context of reviewer feedback, authors of qualitative papers may need to: rethink what theoretical category their empirical phenomenon belongs to; revise their research questions; join different theoretical conversations than those originally envisioned; redo data analysis; collect additional data; and/or fundamentally reposition the paper’s theoretical contribution (cf., Corley et al., 2021).

Our experience also leads us to observe that data themselves might be regarded as part of the context that matters in a research project, or in writing a particular paper. Johns (1991) has noted that any data that is collected may be “constrained” in ways not anticipated by those collecting it. In our experience as qualitative researchers, it is not uncommon to find that the data that has been or can be collected for a particular case may stop short of allowing us to fully examine processes or patterns we intuitively believe should be present. Conceptual insights may be inspired by our knowledge of the empirical context and the data we have collected but not directly supported by the data itself. This means that qualitative researchers are often grappling not just with the question “what is this an instance of?” but also the question “what is this an instance of that my data can explain and that hasn’t been explained by the literature?”

What do these aspects of context mean for qualitative researchers? First, they mean that researchers should not imagine that research design choices can all (or even mostly) be made in advance. Articles that implicitly suggest that the choice of a specific approach to collecting and analyzing case data is a one point-in-time decision are not well aligned to the realities of conducting qualitative research. While WPPP’s four quadrant typology might distinguish different types of cases after the fact, this should not be taken to imply that researchers can make, and stick with, initial articulations about what kind of case studies they will conduct. Given the evolution of research projects and research papers, research designs will continue to change over the life of projects and particular papers. The contingent, unfolding nature of qualitative research projects and papers should not be regarded as a barrier to quality, but as something that can make good research even better. For example, the Bresman, Birkinshaw, & Nobel (1999) paper, winner of the JIBS Decade Award in 2009, was the result of combining insights from two different research projects (Birkinshaw et al., 2010). This is but one illustration of the emergent nature of research design. We encourage qualitative researchers to acknowledge emergent design choices in their methods section both on initial submission and as review processes evolve.

In parallel, we encourage gatekeepers to foster fuller transparency in the research design descriptions in manuscripts they review. In particular, gatekeepers should recognize and be tolerant of the fact that the justification of the selection of empirical cases may well be an after-the-fact justification versus an a priori one. In general, gatekeepers should anticipate that researchers whose work they are reviewing will have faced shifting contexts in the course of their research and will have had to adapt accordingly. Jarzabkowski et al. (2021: 72) have noted that that the appraisal of qualitative research (and indeed of research in general) needs to strike a balance between accountability and professionalism. Accountability directs us to expect that researchers’ actions and decisions are disclosed and well justified, while professionalism directs us to recognize that our fellow professionals need – and can be trusted – to have space for judgement and discretion. We whole-heartedly agree. And we believe that this insight should lead to us to encourage disclosure of, and adjudicate even-handedly, idiosyncratic twists and turns in the research designs of the papers we review.

CONCLUSION

We congratulate Catherine Welch, Rebecca Piekkari, Emmanuella Plakoyiannaki and Eriikka Paavilainen-Mäntymäki on receiving the 2021 Decade Award for writing the most influential paper published in JIBS in 2011. We acknowledge and appreciate the important role they have played in helping to legitimate qualitative research in IB. We hope that our reflections on their work will help to legitimate these methods further. Even more, we hope that our discussion of the various ways that context can be considered when using qualitative methods will help to advance an ever more plural future for international business research.

REFERENCES

Aguilera, R. V., & Grøgaard, B. 2019. The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(1): 20–35.

Askegaard, S., & Linnet, J. T. 2011. Towards an epistemology of consumer culture theory: Phenomenology and the context of context. Marketing Theory, 11(4): 381–404.

Balogun, J., Jarzabkowski, P., & Vaara, E. 2011. Selling, resistance and reconciliation: A critical discursive approach to subsidiary role evolution in MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(6): 765–786.

Bartunek, J. M., Rynes, S. L., & Ireland, R. D. 2006. What makes management research interesting, and why does it matter? Academy of Management Journal, 49(1): 9–15.

Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., & Roth, K. 2017. An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(1): 30–47.

Beugelsdijk, S., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Meyer, K. E. 2020. A new approach to data access and research transparency (DART). Journal of International Business Studies, 3(2): 887–905.

Birkinshaw, J., Bresman, H., & Nobel, R. 2010. Knowledge transfer in international acquisitions: A retrospective. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(1): 21–26.

Bluhm, D. J., Harman, W., Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. 2011. Qualitative research in management: A decade of progress. Journal of Management Studies, 48(8): 1866–1891.

Bresman, H., Birkinshaw, J. M., & Nobel, R. 1999. Knowledge transfer in international acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(4): 439–462.

Brouthers, K. D. 2002. Institutional, cultural and transaction cost influences on entry mode choice and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2): 203–221.

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, L. J., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. 2007. The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 499–518.

Busse, C., Kach, A. P., & Wagner, S. M. 2017. Boundary conditions: What they are, how to explore them, why we need them, and when to consider them. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4): 574–609.

Caligiuri, P. 2014. Many moving parts: Factors influencing the effectiveness of HRM practices designed to improve knowledge transfer within MNCs. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1): 63–72.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. L. 2008. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: Sage Publications.

Corley, K., Bansal, P., & Yu, H. 2021. An editorial perspective on judging the quality of inductive research when the methodological straightjacket is loosened. Strategic Organization, 19(1): 161–175.

Cornelissen, J., Höllerer, M. A., & Seidl, D. 2021. What theory is and can be: Forms of theorizing in organizational scholarship. Organization Theory, 2: 1–9.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. 2000. The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research: 1–28. London: Sage.

Dolbec, P., Fischer, E., & Canniford, R. 2021. Something old, something new: Enabled theorizing in qualitative marketing research”. Marketing Theory, 21(4): 443–461.

Dyer Jr, W. G., & Wilkins, A. L. 1991. Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Academy of Management Review, 16(3): 613–619.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4): 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 2020. Theorizing from cases: A commentary. In L. Eden, B. B. Nielsen, & A. Verbeke (Eds.), Research methods in international business: 221–227. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 2021. What is the Eisenhardt method, really? Strategic Organization, 19(1): 147–160.

Eisenhardt, K. M., Graebner, M. E., & Sonenshein, S. 2016. Grand challenges and inductive methods: Rigor without rigor mortis. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4): 1113–1123.

Geary, J., & Aguzzoli, R. 2016. Miners, politics and institutional caryatids: Accounting for the transfer of HRM practices in the Brazilian multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(8): 968–996.

Gehman, J., Glaser, V. L., Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D., Langley, A., & Corley, K. G. 2018. Finding theory–method fit: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(3): 284–300.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1): 15–31.

Grodal, S., Anteby, M., & Holm, A. L. 2020. Achieving rigor in qualitative analysis: The role of active categorization in theory building. Academy of Management Review.. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0482.

Harley, B., & Cornelissen, J. 2020. Rigor with or without templates? The pursuit of methodological rigor in qualitative research. Organizational Research Methods.. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120937786.

Jackson, G., & Deeg, R. 2008. Comparing capitalisms: Understanding institutional diversity and its implications for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4): 540–561.

Jarzabkowski, P., Langley, A., & Nigam, A. 2021. Navigating the tensions of quality in qualitative research. Strategic Organization, 19(1): 70–80.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. 2009. The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9): 1411–1431.

Johns, G. 1991. Substantive and methodological constraints on behavior and attitudes in organizational research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 49(1): 80–104.

Johns, G. 2006. The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2): 386–408.

Jonsson, A., & Foss, N. J. 2011. International expansion through flexible replication: Learning from the internationalization experience of IKEA. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(9): 1079–1102.

Kirkman, B. L., Lowe, K. B., & Gibson, C. B. 2006. A quarter century of culture’s consequences: A review of empirical research incorporating Hofstede’s cultural values framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(3): 285–320.

Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. 2004. Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 124–141.

Kostova, T., & Hult, G. T. M. 2016. Meyer and Peng’s 2005 article as a foundation for an expanded and refined international business research agenda: Context, organizations, and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(1): 23–32.

Langley, A. 1999. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4): 691–710.

Langley, A., & Abdallah, C. 2011. Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. Research Methodology in Strategy and Management, 6: 201–235.

Lerman, M. P., Mmbaga, N., & Smith, A. 2020. Tracing ideas from Langley (1999): Exemplars, adaptations, considerations, and overlooked. Organizational Research Methods.. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120915510.

Li, J., & Fleury, M. R. T. L. 2020. Overcoming the liability of outsidership for emerging market MNs: A capability-building perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(1): 23–37.

Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. 2005. Probing theoretically into Central and Eastern Europe: Transactions, resources, and institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(6): 600–621.

Minbaeva, D., Fitzsimmons, S., & Brewster, C. 2021. Beyond the double-edged sword of cultural diversity in teams: Progress, critique, and next steps. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(1): 45–55.

Minbaeva, D., Pedersen, T., Björkman, I., Fey, C. F., & Park, H. J. 2003. MNC knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity, and HRM. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(6): 586–599.

Monaghan, S., & Tippmann, E. 2018. Becoming a multinational enterprise: Using industry recipes to achieve rapid multinationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(4): 473–495.

Monroe, K. R. 2018. The rush to transparency: DA-RT and the potential dangers for qualitative research. Perspectives on Politics, 16(1): 141–148.

Pham, M. T., & Oh, T. T. 2021. Preregistration is neither sufficient nor necessary for good science. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1): 163–176.

Pratt, M. G. 2009. For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5): 857–862.

Pratt, M. G., Kaplan, S., & Whittington, R. 2020a. Editorial essay: The tumult over transparency: Decoupling transparency from replication in establishing trustworthy qualitative research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(1): 1–19.

Pratt, M. G., Sonenshein, S., & Feldman, M. S. 2020b. Moving beyond templates: A bricolage approach to conducting trustworthy qualitative research. Organizational Research Methods.. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120927466.

Ragin, C. 1992. “Casing” and the process of social inquiry. In C. Ragin, & H. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring foundations of social inquiry: 217–226Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ravamurti, R., & Hillemann, J. 2018. What is “Chinese” about Chinese multinationals? Journal of International Business Studies, 49(1): 34–48.

Reay, T., Zafar, A., Monteiro, P., & Glaser, V. 2019. Presenting findings from qualitative research: One size does not fit all! Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 59: 201–216.

Shaver, J. M. 2013. Do we really need more entry mode studies? Journal of International Business Studies, 44(1): 23–27.

Shenkar, O. 2001. Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3): 519–535.

Siggelkow, N. 2007. Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1): 20–24.

Stahl, G. K., Maznevski, M. L., Voigt, A., & Jonsen, K. 2010. Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4): 690–709.

Tenzer, H., Pudelko, M., & Harzing, A. W. 2014. The impact of language barriers on trust formation in multinational teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(5): 508–535.

Van Maanen, J., Sørensen, J. B., & Mitchell, T. R. 2007. The interplay between theory and method. Academy of Management Review, 32(4): 1145–1154.

Walton, J. 1992. Making the theoretical case. In C. C. Ragin, & H. S. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry: 121–138Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mantymaki, E. 2011. Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5): 740–762.

Winter, S. G., & Szulanski, G. 2001. Replication as strategy. Organization Science, 12(6): 730–743.

Yin, R. K. 2009. Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). London: Sage.

Zaheer, S., Schomaker, M. S., & Nachum, L. 2012. Distance without direction: Restoring credibility to a much-loved construct. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(1): 18–27.

Zander, I., McDougall-Covin, P., & Rose, E. L. 2015. Born globals and international business: Evolution of a field of research. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(1): 27–35.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Tima Bansal, Kathy Eisenhardt, Sinéad Monaghan, Innan Sasaki, and Esther Tippmann for their insights on earlier drafts of this commentary. We are grateful for the financial support of the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Alain Verbeke, Editor-in-Chief, 4 August 2021. This article was single-blind reviewed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reuber, A.R., Fischer, E. Putting qualitative international business research in context(s). J Int Bus Stud 53, 27–38 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00478-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00478-3