Abstract

This article investigates two important research gaps in international business (IB): how entrepreneurs evaluate international entrepreneurial opportunities (IEOs) and the role of time in the evaluation process. Drawing on the literature on decision-making models and the philosophical foundation of opportunity, this study employs Gioia’s methodology and content analysis to examine how the founders of 15 early-internationalizing firms evaluated IEOs in the early- and late-stage of internationalization. The findings reveal that the interaction of time and three general rules of IEO evaluation that I coin ‘simple’, ‘revised’, and ‘complex’ influenced the entrepreneurs’ decisions. The findings show that the founders transitioned from simple to revised and to complex rules in the IEO evaluation process and that various contingent factors such as time pressure, resource availability, and type of stakeholders drove these transitions. The three general rules correspond to what I label as ‘opportunity actualization’, ‘revision’, and ‘development maximization’ processes, respectively. I propose a Time-based Process model that reconciles extant internationalization models’ (i.e., Process, Network, Economics, and Entrepreneurship) different explanations regarding why and how firms internationalize.

Résumé

Cet article étudie deux gaps de recherche importants en international business (IB) : comment les entrepreneurs évaluent les opportunités entrepreneuriales internationales (OEI) et le rôle du temps dans le processus d’évaluation. En nous appuyant sur la littérature concernant les modèles de prise de décision et le fondement philosophique de l’opportunité, cette étude utilise la méthodologie de Gioia et l’analyse de contenu pour examiner comment les fondateurs de 15 entreprises à internationalisation précoce ont évalué les OEI à l’étape initiale et à l’étape finale de l’internationalisation. Les résultats révèlent que l’interaction du temps et des trois règles générales de l’évaluation OEI que j’appelle ‘simple’, ‘révisée’ et ‘complexe’ ont influencé les décisions des entrepreneurs. Les résultats montrent que les fondateurs ont évolué des règles simples aux règles révisées et complexes dans le processus d’évaluation OEI et que plusieurs facteurs de contingence comme la pression du temps, la disponibilité des ressources et le type de parties prenantes ont conduit à ces transitions. Les trois règles générales correspondent à ce que j’appelle respectivement les processus ‘d’actualisation d’opportunité’, ‘de révision’ et ‘de maximisation de développement’. Je propose un modèle processuel fondé sur le temps qui réconcilie les différentes explications de modèles existants d’internationalisation (c’est-à-dire, processus, réseau, économie et entrepreneuriat) concernant pourquoi et comment les firmes s’internationalisent.

Resumen

Este artículo investiga dos brechas importantes de investigación en negocios internacionales: cómo los emprendedores evalúan las oportunidades empresariales internacionales y el rol del tiempo en el proceso de evaluación. Con base en la literatura en modelos de toma de decisión y la base filosófica de oportunidad, este estudio usa metodología de Gioia y análisis de contenido para examinar como los fundadores de 15 empresas que se internacionalizaron tempranamente evaluaron las oportunidades empresariales internacionales al comienzo y en la última etapa de la internacionalización. Los resultados revelan que la interacción de tiempo y las tres reglas generales de la evaluación de las oportunidades empresariales internacionales que denomino “simples”, “revisadas”, y “complejas” influencian las decisiones de los emprendedores. Los hallazgos muestran que los fundadores pasaron de reglas simples a revisadas y complejas en el proceso de evaluación de oportunidades empresariales internacionales y que varios factores contingentes como la presión de tiempo, disponibilidad de recursos, y tipo de grupos de interés impulsaron estas transiciones. Las tres reglas generales corresponden a lo que etiqueto como procesos de “oportunidad de actualización”, “revisión”, y “maximización de desarrollo”, respectivamente. Propongo un modelo de Proceso basado en el Tiempo que reconcilia las diferentes explicaciones de los modelos de internacionalización existentes (es decir, proceso, redes, economía y emprendimiento) sobre por qué y cómo las empresas se internacionalizan.

Resumo

Este artigo investiga duas importantes lacunas de pesquisa em negócios internacionais (IB): como os empreendedores avaliam as oportunidades empreendedoras internacionais (IEOs) e o papel do tempo no processo de avaliação. Com base na literatura sobre modelos de tomada de decisão e fundamento filosófico da oportunidade, este estudo utiliza a metodologia Gioia e análise de conteúdo para examinar como os fundadores de 15 firmas de precoce internacionalização avaliaram os IEOs nos estágios inicial e final da internacionalização. Os resultados revelam que a interação do tempo e três regras gerais da avaliação das IEO que eu nomeio de “simples”, “revisado” e “complexo” influenciaram as decisões dos empreendedores. As descobertas mostram que os fundadores passaram de regras simples para revisado e complexo no processo de avaliação de IEO e que vários fatores contingenciais tais como pressão de tempo, disponibilidade de recursos e tipo de atores direcionaram essas transições. As três regras gerais correspondem ao que rotulo como processos de “oportunidade de atualização”, “revisão” e “maximização do desenvolvimento”, respectivamente. Proponho um modelo de Processo baseado no Tempo que reconcilia modelos de internacionalização existentes (isto é, Processo, Rede, Economia e Empreendedorismo) diferentes explicações sobre por que e como as empresas se internacionalizam.

摘要

本文研究国际商务(IB)中两个重要的研究空白:企业家如何评估国际创业机会(IEO)以及时间在评估过程中的作用。借鉴关于决策模型和机会的哲学基础的文献,本研究采用Gioia的方法和内容分析来研究15个早期国际化企业的创始人如何在国际化的早期和晚期评估IEO。研究结果表明,时间和IEO评估的三个通用规则即我说的’简单’,’修订’和’复杂’的互动,影响了企业家的决策。研究结果表明,创始人在IEO评估过程中从简单到修订到复杂规则过渡,且各种偶然因素,如时间压力,资源可用性和利益相关者类型驱使这些过渡。三个通用规则分别对应于我标记为‘机会实现’,‘修订’和‘发展最大化’过程。我提出了一个基于时间的过程模型来调和现有的国际化模型(即过程,网络,经济和企业家精神)对企业为什么和如何国际化的不同解释。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing consensus in the international business (IB) literature is that internationalization is, in essence, an entrepreneurial behavior process that occurs over time (Jones & Coviello, 2005; Middleton, Liesch, & Steen, 2011). The internationalization process is based on assumptions about (1) the opportunity to create and capture economic value, (2) the decision-making process underpinning the evaluation of international entrepreneurial opportunities (IEOs), and (3) time, against which all decision-making processes can be explained (Chandra, Styles, & Wilkinson, 2009; Jones & Coviello, 2005; Maitland & Sammartino, 2015; Zahra, Korri, & Yu, 2005). Despite the burgeoning research on internationalization over the past four decades, decision-makers’ cognitive processes in internationalization decisions, and how the processes evolve over time, remain underexplored and poorly understood (Benito, Petersen, & Welch, 2009; Hennart & Slangen, 2015; Maitland & Sammartino, 2015; Zahra, Korri, & Yu, 2005). A growing number of IB scholars have repeatedly highlighted the need to study decision-makers’ decision styles, biases and cognitive processes (e.g., Barkema & Shvyrkov, 2007; Hennart, 2009; Hutzschenreuter, Pedersen, & Volberda, 2007; Williams & Grégoire, 2015) and “to explicitly incorporate the role and influence of time” (Jones & Coviello, 2005: 290) in internationalization research. However, empirical studies remain scarce.

Research on internationalization and on decision-making models underpinning opportunity evaluation has proceeded along fairly divergent tracks, although researchers have recognized the utility of conceptually linking them (Jones & Casulli, 2014; Maitland & Sammartino, 2015; Sarasvathy, Kumar, York, & Bhagavatula, 2014; Zahra et al., 2005). Among the three stages of internationalization, discovery → evaluation → exploitation (Oviatt & McDougall, 2005; Coviello, 2015), the evaluation process is central to the study of the entrepreneur’s decision-making and, arguably, the most critical construct in studies that will advance internationalization research and practices. Research on opportunity evaluation could help bridge the critical gap between opportunities and action (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Williams & Wood, 2015). This can reconcile the inconsistent findings in IB research regarding why and how firms internationalize (Axinn & Matthyssens, 2002; Benito, Petersen, & Welch, 2009; Buckley, Devinney, & Louviere, 2007; McDougall, Shane, & Oviatt, 1994) and to explain the emerging IB phenomena (e.g., ‘born globals’ from emerging markets, Cavusgil & Knight, 2015; Uner, Kocak, Cavusgil, & Cavusgil, 2013; ‘consumers as international entrepreneurs’, Chandra & Coviello, 2010; and the globalization of sharing-economy models like Uber, Laamanen, Pfeffer, & Van de Ven, 2016). Moreover, opportunity evaluation research entails a critical examination of the worldviews (i.e., philosophy or ontology) of IEOs, which could advance internationalization research through a new interpretation of ‘opportunity’ and its underlying assumptions in internationalization models. The lack of research on opportunity evaluation also plagues entrepreneurship research where scholarship has “advanced very little in our knowledge of how entrepreneurs evaluate [opportunities] … their decisions to exploit opportunities … [and that] entrepreneurship should be studied as a process” (Shane, 2012: 4).

One approach to exploring the opportunity evaluation gap employs the effectuation perspective (Sarasvathy, 2001). The effectuation perspective, derived from the entrepreneurial decision-making research, is a problem-solving approach that eschews prediction or planning and uses practices aimed to control uncertainty, including the affordable-loss principle, contingency leveraging, and market co-creation with stakeholders (Sarasvathy et al., 2014; Sarasvathy, 2001). The small body of internationalization research that employs the effectuation lens has studied the extent of effectuation in international new venture creation (Harms & Schiele, 2012), the application of effectuation on internationalization (Chetty, Ojala, & Leppäaho, 2015; Andersson, 2011), and the implications of effectuation on the internationalization process (Kalinic, Sarasvathy, & Forza, 2014). Despite their valuable contributions to internationalization research, these studies largely impose the effectuation concept on data (rather than ‘letting the data speak’ to inform theory development), and they focus on the static, atemporal aspect of the entrepreneur’s decision-making. Time is, first and foremost, a primary conceptual dimension to which explicit behavior may be understood (Ancona, Goodman, Lawrence, & Tushman, 2001). Time is fundamental to internationalization research because “each firm has a history … of internationalisation events occurring at specific points in time” (Jones & Coviello, 2005: 289–290). As a form of entrepreneurial behavior, internationalization is an accumulation of entrepreneurs’ actions over time (Covin & Slevin, 1991). Internationalization is subject to time and the influence of the wider environment. This raises the question as to whether and how entrepreneurs utilize decision-making models (e.g., effectuation, causation) to evaluate IEOs, and in what way(s) time influences the opportunity–evaluation processes. This also raises questions of whether and how entrepreneurs consider the different worldviews of IEOs (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016).

These are key research questions, and provide an opportunity to advance IB scholarship. Accordingly, this study asks: How do entrepreneurs evaluate international entrepreneurial opportunities? What role does time play in international entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation?

This article first reviews the influential internationalization models, which reveals that opportunity evaluation and temporal effects on decision-making remain unexplored. To fill this gap, this article places evaluation and temporal effects front and center. It does not assume, like most studies, that internationalization is a simple sequential process (i.e., IEO discovery → evaluation → exploitation). It also allows for a flexible interpretation of decision-making models to inform the IEO evaluation processes. In addition, the article explores the philosophical foundation of opportunity to understand the why and how of IEO evaluation processes.

This study’s empirical data are derived from interviews with the founders of 15 early-internationalizing (i.e., firms that internationalize between one to six years after firm inception) small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and their evaluations of 94 early- and late-stage IEOs. ‘Early stage’ refers to the entrepreneur’s evaluation of his/her first internationalization opportunity, plus other opportunities from 2 weeks to 2 months after initiating the first IEO. ‘Late stage’ refers to the entrepreneur’s evaluation of a subsequent internationalization opportunity from 3 to 15 years after the first internationalization. The aim of capturing the early vs late stage IEOs was to see if there are differences in how entrepreneurs evaluated opportunities across time and, if so, why. I conducted the in-depth interviews at multiple time intervals between 2005 and 2012 using both retrospective questions that required them to look back and discuss why and how they evaluated IEOs, and longitudinally to track their evaluation of opportunities ‘as they were happening.’ The interviews were supplemented with other primary and secondary data. The Gioia methodology, a process of coding and aggregating data into theoretical concepts using a data structure, along with a content analysis were employed to examine the founders’ IEO evaluation processes.

This study enhances the IB literature in two important ways. First, by placing opportunity evaluation and time as the central constructs in internationalization research, this article advances our understanding of entrepreneurs’ decision-making process for internationalization (Chetty et al., 2015; Harms & Schiele, 2012; Kalinic et al., 2014; Williams & Grégoire, 2015). This research offers deeply contextualized findings that identify three rules of IEO evaluation employed by early-internationalizing entrepreneurs. It also explains not only how time and the decision rules interact in IEO evaluation but why. Based on the data I collected, the entrepreneurs’ evaluation of early-stage IEOs involves much uncertainty and thus necessitates ‘simple rules’ to help in decision-making. The entrepreneurs used basic ‘or simple rules’ to transform unmet foreign market demand into actual opportunities, a process that I label ‘opportunity actualization’. For example, these simple rules include ‘Exploit any IEO that arises and see if it pays off’ and ‘Rely on the opinions of other entrepreneurial actors (e.g., suppliers, strangers, and business contacts)’. As entrepreneurs learn and make mistakes, they revise their rules. These are called ‘revised rules’ and enable them to differentiate between ‘possibly successful’ and ‘likely unsuccessful’ IEOs, and between major (highly promising) from minor (less promising) IEOs, a process that I label ‘opportunity revision’. For example, these revised rules include ‘The licensee didn’t pay his license fees’ and ‘The agents lost focus and didn’t sell anything’ which prompted them to emphasize on trust and performance as key evaluation criteria. The evaluation of late-stage IEOs, following the actualization and revision of opportunities, gives entrepreneurs a more objective view of the world, and their next step which requires the deployment of ‘complex rules’ that are based on finer heuristics-based and economic-driven criteria, a process that I label as opportunity ‘development maximization’. The simple rules, revised rules, and complex rules form the three general rules of IEO evaluation.

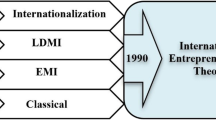

Second, this article develops new insights that reconcile and integrate the various assumptions of internationalization models using the general rules and the ontology of IEOs. In particular, the core logic of the Network model resembles the ‘opportunity actualization process’ of IEOs (following the critical realist view) through the use of the ‘simple rules.’ The simple rules found in this study contribute 10 new types of rules to the Network model, rules that can be categorized as heuristics-, emotion-, and action-based. The core logic of the Process model resembles what I term the ‘revised rules’ of IEOs or the ‘opportunity revision process’, which entrepreneurs need to separate the possible from unlikely IEOs and the major from minor IEOs. The core logics of the Economics and Entrepreneurial models of internationalization resemble what I label as the ‘opportunity development maximization’ process (following empiricist and constructivist views) of IEOs through the use of ‘complex rules.’ These models focus on the less mysterious state of IEOs so that entrepreneurs can better evaluate, search for, maximize and co-develop the IEOs. It demonstrates the workings of the different schools of opportunity in the internationalization process, offering a solution to the puzzle of the ontology of opportunity.

The next section presents the study’s theoretical background. It then discusses the methodology and findings that emerge, and presents a Time-based Process model of IEO evaluation. It discusses the results in light of the internationalization models and offers implications for theory, practice and future IB research.

Theoretical Background

In this section, I will discuss various decision-making models in IB, the ontology of opportunity in IB and re-interpret the Internationalization Models using the decision-making models and ontology of opportunity.

Decision-Making Models in IB: Effectuation, Causation, Rule-Based Reasoning

Decision-making is the core of all IB activities. As such, an understanding of the assumptions and elements of decision-making models is critical to advance IB research. Effectuation is an important decision-making model that lends insight into how entrepreneurs evaluate opportunities. It focuses on controlling uncertainty (rather than predicting or planning) and leveraging contingencies, and employs the affordable-loss principle and satisficing as evaluation criteria (Sarasvathy et al., 2014; Sarasvathy, 2001; Wiltbank, Dew, Read, & Sarasvathy, 2006). Effectuators start with the existing means (e.g., identity, knowledge, networks, resources) and ask how these can be transformed into products, organizations, markets and the like, by engaging stakeholder networks that help shape the means and goals.

Effectuators initiate the decision-making process by analyzing ‘Who am I?’ (e.g., a seasoned entrepreneur with a passion for high tech products), ‘What do I know?’ (e.g., I always relied on intuition to make decisions), ‘Whom I know?’ (e.g., my business contacts, A, B and C are in country X, Y, and Z and in the fields of D, E, and F) and ‘What I can do?’ (e.g., I can pursue a global opportunity by commercializing a new software developed by A and using the resources owned by B and C). In contrast, the causation approach aims to maximize expected returns, avoid surprises through careful prediction, planning and opportunity analysis. Those practicing the causal approach start with a goal and work backwards to find the means to achieve it. Causal thinkers analyze ‘What is my goal?’ (e.g., I need to make X amount of profit within Y number of years), ‘How do I optimize outcomes?’ (e.g., choose partner B and country Z as to get the best result), and ‘Which decision is less risky?’ (e.g., option A is better than other options based on data available; developing a careful market survey or business plan is a less risky approach to doing IB). Therefore, effectuation and causation are exact opposites. Entrepreneurs who espouse effectuation tend to (1) weigh predictive information (e.g., market research, demand estimates) more critically than causation adherents, and (2) draw on personal experience more than causation adherents, and iii) aim for affordability (Dew, Read, Sarasvathy, & Wiltbank, 2009; Jones & Casulli, 2014) more than causation types.

Rule-based reasoning, a more recent theoretical approach in entrepreneurship scholarship, is a structured approach to opportunity evaluation. It relies on rules so as to reduce uncertainty and to assess opportunities against specific criteria (e.g., financial return, competition level) to help decide if an opportunity is exploitable (Wood & Williams, 2014; Williams & Wood, 2015). Rules serve as “analytical knowledge structures” (Williams & Wood, 2015: 221) to make logical inferences (e.g., if S, then A, then C (S = situation, A = antecedent, and C = consequences)). For example, a rule-based thinker analyzes the IB market by asking: If country market A is too competitive then I will pursue country Y or Z (i.e., competition as a rule); if demand in country market B is lower than expected, then I will use approach X to succeed in that market (market demand as a rule). Despite its promise, few empirical studies show how rule-based reasoning occurs ‘over time’ (Williams & Wood, 2015: 230; Wood & Williams, 2014). As will be shown later, the rule-based reasoning literature offers a point of departure in developing a process model of the IEO evaluation process.

The Ontology of Opportunity in IB: Empiricism, Constructivism, Critical Realism

Opportunity is a central construct in entrepreneurship (Shane, 2012) and in IB because operating an international business involves the discovery, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities (Jones & Coviello, 2005). An understanding of the worldviews (i.e., ontological views, Harre, 2002; Tsoukas & Knudsen, 2003) of opportunity is critical to advancing IB research. The empiricist view (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016; Ramoglou, 2013) is based on an objective view of the world and assumes that opportunities ‘exist out there’ in international markets. Because opportunity exists in an objective realm, it can be evaluated based on its various attributes (e.g., production costs, labor supply, and stability of foreign government). In contrast, the constructivist view (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016) subscribes to a socially constructed (subjective) worldview and portrays opportunities as ‘created and or co-created’ through relationships and interactions among stakeholders in international markets. An ongoing debate between the two ontological views of opportunity focuses on whether opportunity is in actuality an objective or subjective phenomenon (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016; Suddaby, Bruton, & Si, 2015). The critical realist view (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016; Ramoglou, 2013), which recently entered the discourse, argues that opportunities are unrealized abstract possibilities that need to be concretized. This view recognizes that reality in IB is structured on three assumptions: (1) endless possibilities exist, represented by ‘the real world’, which offers the largest set of possibilities and where raw opportunities can be found internationally, (2) un-actualized possibilities exist, represented by ‘the actual world’, which contains unexploited IB opportunities and is a subset of ‘the real world’ and (3) observable reality, seen as ‘the empirical world’, which contains possible and unlikely IB opportunities as the smallest subsets. Hence, realists acknowledge unactualized opportunities that can be ‘evaluated’ and prospects that can be enhanced through market intervention (e.g., creating an entrepreneurship hub such as Silicon Valley) and that they also recognize that entrepreneurs’ efforts are necessary (e.g., mobilizing resources, creative marketing efforts) to actualize IB opportunities. Realists emphasize ‘opportunity belief’ (e.g., the degree of confidence about the presence of an opportunity) and the subsequent revision of such belief, and they consider failure as either an unidentified opportunity or un-actualized opportunity due to faults in the execution (i.e., failure due to a lack of competence or commitment or the wrong resource mix to realize an opportunity).

Re-Interpreting the Internationalization Models

Internationalization models essentially assume that opportunities are key for creating economic value and that certain decision-making logics underpin opportunity evaluation. The influential models of internationalization (Economics, Process, Network, and Entrepreneurship) ask different questions about IB opportunities and focus on different ontologies and decision-making aspects in opportunity evaluation. The Economics model (i.e., Ownership-Location-Internalization (OLI) advantages) of opportunity evaluation focuses on decisions that produce the best economic outcomes (e.g., location choice and entry mode), based on what a firm owns (e.g., products, brands, people) (Dunning, 1988, 2000). Those using the Economics model focus on firm-market fit and embrace optimization thinking in IEO evaluation. A typical question asked by a CEO or manager making an internationalization decision under the Economics model is “How can I optimize my company’s choice of location and entry mode given what this company owns, its aspirations and vision?” The Economics model is parallel to the Empiricist view of opportunity (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016; Ramoglou, 2013), which assumes that opportunities ‘exist out there’ in foreign markets and can therefore be evaluated objectively based on various criteria, such as market demand, raw materials supply, and cost factors. This objective view of foreign market opportunities means that firms can choose what they assess to be the best location and type of entry mode to optimally exploit such opportunities. The Economics model is also parallel to the Causation approach as it maximizes expected returns from operating internationally, avoids surprises through careful prediction strategies (e.g., cost–benefit analysis, optimization analysis) and thoroughly plans its steps and analyzes all current and possible problems. However, the Economics model lacks the time effects of opportunity evaluation. For instance, it does not explain whether and how a firm should evaluate early-stage IEOs (i.e., the first and second IEOs) and late-stage IEOs (e.g., IEOs considered many years after the first IEO).

The Process model (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990) focuses on learning and risk mitigation. It focuses on ways that firms can internationalize to new markets from culturally similar to culturally different markets (i.e., successively greater psychic distance) and/or to riskier and more committed entry modes (e.g., from exporting to foreign direct investment). It implies a loop in the evaluation of IEOs at time 1, which feeds into the evaluation at time 2, 3, 4 and so on. A typical question that a CEO or manager using the Process model asks is “How can my company take a safe, incremental approach to succeed in international markets?”, “Based on what we learn from three years of internationalization in the neighboring market X, how can we continue to expand to slightly different foreign markets or employ a riskier entry mode?” This model parallels the Critical Realist view of opportunity (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016; Ramoglou, 2013), which assumes that opportunities are unrealized possibilities in foreign markets but cannot be discovered (realized) unless a focal firm takes action to actualize them. It recognizes endless possibilities, un-actualized IEOs, and the importance of distinguishing between possible and unlikely IEOs as firms learn from foreign markets. The Process model is similar to rule-based reasoning where those evaluating opportunities use knowledge and commitment level as judgment rules. The model positions learning processes as central to the IEO evaluation but does not well explain how IEO evaluation evolves. For instance, do the IEO evaluation rules change across time, from the firm’s startup, growth and mature periods? If so, why and how? If not, why and how? Likewise, the Process model does not fully explain how IEO evaluation rules drive early internationalization.

According to Johanson and Mattsson (1986, 1988), the Network model sees markets as networks; they theorize that firms internationalize by networking with organizations through their formal and informal relationships and that the (often unintended) effects of these relationships help advance the internationalization process. A typical example of the Network model is an entrepreneur meeting a business person on a transcontinental plane trip and discovering an opportunity worth exploring through a long discussion ranging from their common interests, insights and experience. Like the Process model, the Network model aligns with the Critical Realist view of opportunity (Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016) and views networks as providing endless possibilities discovered through interactions with local and foreign networks. This model also aligns with the Effectuation approach as it emphasizes the unintentional process of networking and market entry, particularly for smaller firms. Despite its relevance to SMEs, the Network model lacks the time-sensitive aspects of IEOs evaluation. For instance, it does not explain the role of networks in the early vs late stages of IEO evaluation. Nor does it explain the logic behind the prevalent use of relationships in identifying IEOs.

The Entrepreneurship model (Coviello, 2015; Jones & Coviello, 2005; McDougall & Oviatt, 2000) shifts the discourse on internationalization to opportunities as it attempts to explain IB development patterns such as early or fast internationalization and international new ventures. It views internationalization as a process and outcome of entrepreneurial action under uncertainty. A typical question an entrepreneur using the Entrepreneurship model asks is “How do I make this new invention into a global business opportunity?”, “How can I work with partners to collaboratively pursue this opportunity as quickly as possible?” This model see opportunities as created or co-created by actors and their peers (Constructivist view) and discovered as realities ‘out there’ in foreign markets (Empiricist view; see Alvarez, Barney, & Anderson, 2013; Ramoglou & Tsang, 2016). Of the four internationalization models, the Entrepreneurship model is the only one to identify the opportunity-identification and exploitation-stages of opportunity (Chetty et al., 2015; Zahra et al., 2005).

As discussed above, the temporal aspect of IEO evaluation is largely overlooked in internationalization research. Importantly, very little research unpacks the decision-making models to explain how entrepreneurs evaluate international opportunities.

Method

Data Collection

Since the decision-making process used in evaluating IEOs is complex, we need to “unravel the underlying dynamics of phenomena that play out over time” (Siggelkow, 2007: 22). This suggests a need to gather rich, in-depth data. This study uses inductive research because it can help answer the core question of internationalization research: How do entrepreneurs evaluate opportunities? This study employs a process-oriented approach to examine multiple cases with an embedded design (Van de Ven & Engleman, 2004; Yin, 2003). That is, to study entrepreneurs’ evaluation processes, I gathered information from informants on the multiple IEOs that each considered.

Conducting multiple case studies, like conducting multiple experiments, enables replication that can enrich insights or challenge assumptions (Eisenhardt, 1989). Accordingly, it can advance theory-building research such as this. The theoretical constructs of interest – IEO evaluation and time – and the derivable insights influenced the choice of sampling for this research. A review of the extant research on decision-making models in IB (e.g., effectuation) reveals a lack of research beyond the European-focused context (e.g., Finland, Germany, Sweden; Andersson, 2011; Chetty et al., 2015; Harms & Schiele, 2012; Kalinic et al., 2014; Galkina & Chetty, 2015). Australia, the focal country in this study, has a relatively small open economy that is heavily reliant on export. As such, it offers a new comparative context to study IB decision-making models to help enrich, extend and even challenge existing knowledge – an important consideration for theory-building research.

For this study’s theoretical sampling, I selected cases that were early internationalizers (i.e., those internationalizing within 6 years after inception; Coviello, 2015; Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, 2000) and assessed whether and how their evaluation of early- and late-stage IEOs differed, and why. I selected the cases from a pool of SMEs based in Australia using business and government directories (i.e., Kompass database, Australian Technology Showcase, Australian Trade Commission), three leading Australian business magazines, Business Review Weekly, Australian Business Solutions, Business First Magazine, and three major Australian newspapers, The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald, Australian Financial Review. The cases contain well-experienced entrepreneurs and novice entrepreneurs from the knowledge-based (KB) and non-knowledge-based (NKB) economic sectors in an effort to rule out the possibility that experience and sector differences affect IEO evaluation. This purposeful sampling included locally owned small- to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (less than 200 employees) that were Proprietary Limited and/or Partnership entities (but not publicly traded or government-owned firms), in which the founders or key executives instrumental in the internationalization process were still at the helm and agreed to participate in the study.

Of the 60 firms contacted from the firm database described above, 15 firms responded positively and became the focus of this study. They comprise eight cases from the KB and seven cases from the NKB sectors. All 15 firms internationalized between 1 to 6 years after start-up. Table 1 offers a summary of these 15 cases. In total, I conducted 59 interviews with 39 individuals between 2005 and 2012 and tracked all the firms’ IEO evaluation over this period of time. These comprise 33 founders who were also CEOs of the focal cases and their close associates (i.e., co-founders, high-level managers), plus six expert informants outside the companies who were familiar with the founders (i.e., venture capitalists, government officials) to gain deeper insights into the cases. In addition, I collected 603 pages of internal documents (e.g., business contracts, business plans, product sheets) and conducted 40 on-site visits. The fieldwork generated 99 h of taped verbal data, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber. As Table 1 shows, the cases include entrepreneurs in the healthcare, manufacturing, software, fashion and beverage businesses. To provide anonymity, all of the firm’s names used here (e.g., OdorCo, SportCo) are pseudonyms. These pseudonyms also serve to aid recall and analyses; for instance, ‘OdorCo’ refers to a firm that manufactures chemicals for odor control, while ‘SportCo’ refers to a firm that manufactures sportswear.

The primary data were supplemented by on-site observations, email exchanges, phone and Skype conversations, and company public web-based materials and news articles. Specifically, I asked each informant to discuss how they evaluated international opportunities, specifically: (1) timing and considerations (i.e., early- vs late-stage opportunities: “What was your first (next, recent) international opportunity? What factors or issues did you consider when pursuing opportunity X? Did you consider other opportunities?”), (2) magnitude (i.e., “Was an opportunity a significant for you or not?”), and (3) failure/success (i.e., “What is difficult about doing business internationally? Did you ever fail, or make mistakes? Of all of your ventures, what was the most successful?”). I then probed for deeper meaning with follow-up questions such as “What do you mean by that? Can you provide examples of this?” (Lamb, Sandberg, & Liesch, 2011). I asked ‘who, when, where, what, which, how, why’ questions (Pettigrew, Woodman, & Cameron, 2001 : 700) to stimulate narratives that reveal the thinking behind decisions, actions, events and relationships. I also asked the entrepreneurs to indicate their firms’ overall performance over the period of the study using an ordinal scale of ‘low, medium, high, to very high.’ This information was cross-checked for consistency using the interviewees’ verbal responses on the overall state of the firms, the presence/absence of major deals and or financial losses and gains, and their confidence about the business.

The interviews were both retrospective and longitudinal for two reasons: first, to capture past internationalization events, decisions, actions that had occurred prior to the first interviews, and second, to follow each case’s important internationalization event ‘as it was happening’ (as much as possible), along with the informants’ thoughts, feelings, and perceptions (McMullen & Dimov, 2013). Rapport building with the interviewees was critical and so I frequently emailed them to say ‘Hello’ and to convey information about the study and its goals to enhance their willingness to share information throughout the 7-year period. For all 15 cases, interviews took place within a few days to one week after the internationalization event, defined as any signature inked on a deal or legally binding commitment (made on paper) made by the focal firm. This timely follow-up was made possible due to the close rapport developed between the researcher and informants. This step helped to mitigate recall bias. The interviews range from three to five times, except for two cases (i.e., WaterCo and SportCo, which had two interviews each; see Table 1), because the informants were busy. I promised anonymity and confidentiality (via a written and signed agreement) and was able to obtain a high level of candor and access to privileged documents and detailed information related to internationalization decisions. I requested and collected concrete evidence of internationalization (i.e., transaction sheets, client/partner’s specific name, year and significance of the internationalization event or decision, photos of products and the physical firms, sample products, and IB correspondence) again, with assurance of full confidentiality. The first-round of interviews (15 interviews for the 15 cases) were face-to-face and lasted 1 to 3 h and adhered to a semi-structured interview protocol. The subsequent interviews were conducted by telephone (19 interviews) or Skype (10 interviews) and others were face-to-face (15 interviews) and lasted between 30 min to 1 h. The multiple sources of evidence and informants’ confirmation of data content helped ensure research validity and reliability (Yin, 2003 ). Additionally, I asked the informants to review the interview transcript and confirm that the information, events and decisions were correct.

Data Analysis

The data collection and initial stages of data analysis overlapped over seven years during which time I cycled between the data, themes, concepts, dimensions and the relevant literature (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, 2013; Nag & Gioia, 2012). Thus the data and theory were considered together (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007). The data analysis focused on the entrepreneur’s or his/her leadership team’s actions and/or decisions in pursuit of IEOs. I started with within-case analyses and proceeded with cross-case analyses.

I coded all the data using computer-aided qualitative data analysis (RQDA) software, an open-source program within the R statistical computing environment (Chandra & Shang, 2017; Huang, 2014). I coded conservatively by including only what was explicit in the data; that is, I did not infer intentionality. For analytic clarity, ‘early stage’ IEO refers to the entrepreneur’s evaluation of his/her first internationalization opportunity. For entrepreneurs who evaluated a second (different) IEO near the first IEO, ‘early stage’ refers to doing so from 2 weeks to 2 months after initiating his/her first IEO. A ‘late stage’ IEO refers to the entrepreneur’s evaluation of subsequent internationalization between three and 15 years after his/her initial internationalization.

I identified and examined the decisions and/or events based on the primary and secondary data sources, with two IB experts critiquing the interpretation process (Gioia et al., 2013). I conducted consistency checks (Weber, 1990) and carefully coded all textual data, allowing multiple coding of each textual unit. For example, the response, “we signed up any agents and decided later if they were good for us” could be coded as the ‘exploit-then-evaluate’ rule because the action preceded evaluation, or as the ‘least-effort’ rule if the coder felt that easy-to-pass criteria were used).

Subsequently, I conducted a cross-case analysis and coded the textual data as first-level codes and further aggregated them to second-level codes and aggregate dimensions following Gioia’s methodology (e.g., Gioia et al., 2013; Nag & Gioia, 2012). For instance, during the data analysis “I target the most recognizable trade fairs, multinational companies, or locations”, “I just pursued whichever opportunities that came first”, “We don’t have a strategy like those taught in the textbook” were emerging in the first-level codes and coded respectively as ‘recognition rule,’ ‘least-effort rule,’ and ‘no-rule’ which I aggregated into ‘heuristics-based’ rules as a second-level code. This, along with other second-level codes such as ‘emotion-based, action-based and outside-opinion based’ rules were then abstracted as ‘simple’ rules (see Table 2). Following a peer review by two IB experts, the data structure was finally simplified into 30 first-level codes which were aggregated into 10 s-level codes – containing 10 IEO evaluation rules – and finally three aggregate dimensions – comprising three general IEO evaluation rules (Table 2). I then probed the data to find when in the decision process the entrepreneurs used each evaluation rule (i.e., early or late stage), and the drivers and outcomes of the rules used, as shown in Table 2.

Next, I formed two teams, myself and two IB experts on one team and two PhD students who had been trained to code on other team, to independently analyze the IEO-relevant data using the inductively derived variables (e.g., rules based on heuristics, emotions, or action) as the coding scheme. Collectively, the research team assessed 94 IEOs evaluated by the informants and coded 151 evaluative dimensions (see Table 3). The detailed case-by-case analysis, along with their IEO evaluation rules used across time are available in Web Appendices 4 and 5. Finally, I developed a grounded model that linked the various concepts and patterns that emerged.

Findings

This study revealed three central findings detailed in Figure 1. First, entrepreneurs’ decision-making models for developing IB centered on three general IEO evaluation rules labeled simple, revised and complex. Each general rule contains sub-rules, which offer more specific nuances of the types of opportunity evaluation used by the entrepreneurs (cf. Table 2). Second, time and other contingencies influenced IEO evaluation rules use, where entrepreneurs transitioned from simple to revised to complex rules over time. Third, there is a parallel between the three general IEO evaluation rules and each of the influential internationalization models (i.e., Process, Network, Economics, and Entrepreneurship) such that each model may guide entrepreneurs’ use of different IEO evaluation rules and their worldviews about opportunities. In the next section, I first report important contextual background and then present the most representative findings from each theme that emerged in the study.

First, all of the serial and novice entrepreneurs interviewed had substantial business and management and/or entrepreneurial experience (Table 1). None were fresh university graduates when they started the business. Half of the informants had no experience in the IEO business sector they entered (e.g., one had a background in accounting and another in biotechnology, SeaweedCo and BioactiveCo, respectively) and the rest had low to high experience in the business sector they entered (e.g., one had managed a cafe and started a grilled chicken restaurant (GrillCo) and another had SAP programming experience and entered SAP consulting (SAPCo)). Their IB experience ranged from high among the eight serial entrepreneurs to low among the seven novice entrepreneurs.

Second, during the startup phase, none of the entrepreneurs relied heavily on personal resources but embraced the bricolage principle (making do with what is at hand; Baker & Nelson, 2005) to start up the business. One entrepreneur, for example, repurposed machines previously used to manufacture industrial brushes for wine cork production (CorkCo), another used a management consulting office space he/she rented to start a DNA diagnosis equipment business (DNACo), and an another entrepreneur used a rent-free salon whose lease term was about to expire to experiment with a new no-frills salon concept (HairCo).

Third, all of the entrepreneurs internationalized early on – within 6 years after inception (see Table 1). Their early internationalization was driven by various factors including the time pressure to recoup investment amid their recognition of global opportunities (e.g., BioactiveCo, CorkCo, DNACo, SeaweedCo), serendipitous discovery by foreign businesses (e.g., OdorCo, HairCo, RipeCo, SportCo, ClothCo), the founder’s or co-founder’s existing contacts with foreign business players (e.g., ColorCo, SAPCo, TelcoCo, GrillCo), and familiarity with the IB environment such as Europe (e.g., WaterCo and JuiceCo).

In general, this study found differences in how the entrepreneurs evaluated IEOs across time (‘early vs late-stage’ IEOs) and that the evaluation rules to assess IEOs had influenced the firm’s performance. For the early-stage IEOs, the entrepreneurs were more focused on actualizing non-existent opportunities into actual opportunities and in so doing they relied on ‘simple’, ‘fast’ and ‘frugal’ approaches. At this stage, achieving high firm performance (i.e., sales and profit) was not on the entrepreneurs’ agenda, in fact 11 cases had ‘low’ firm performance (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). Through mistakes and learning in internationalizing their businesses, the entrepreneurs were able to refine the ways they evaluated IEOs and weed out promising from unlikely IEOs. In the late-stage IEOs, as the international markets had become less mysterious to the entrepreneurs, the entrepreneurs generally relied on ‘prudent’, ‘calculative’, and ‘optimizing’ approaches. In 10 cases, this led to ‘high and very high’ firm performance (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). Overall, the data suggest that the entrepreneurs engaged in ‘finding’ and ‘being found by’ opportunities. Regardless of the source of opportunities (finding or being found), what were the entrepreneurs’ decision-making processes in shaping the IEOs that led to firm internationalization? The next section discusses these processes in greater depth.

Simple Rules When Evaluating Early-Stage IEOs

All entrepreneurs employed ‘simple rules’ to evaluate early-stage IEOs. The data revealed that all entrepreneurs used 13 simple rules aggregated into four broad categories: (1) heuristic-based (“What shortcut can I use?”); (2) emotion-based (“What do I feel?”); (3) action-based (“What I can do?”); and (4) outside-opinion-based (“What do others say?”), described below. These revealed a mixture of use of rules of thumb, emotion, action, and opinions of other entrepreneurial actors to evaluate IEOs. Table 2 offers a broad overview of each of the 13 simple rules (along with other 17 rules in the study) and Web Appendix 1 shows detailed examples for the simple rules. Due to space limitations, I describe only the most important evaluation rules for each category.

Heuristics-Based Rules (“What Shortcut Can I Use”?)

The Recognition rule is a heuristics-based evaluation rule that refers to targeting the largest entities such as international clients, producers and tradeshows (see Table 2 and Web Appendix 1). For instance, the founders of DNACo and CorkCo referred to “the top three DNA labs in the US” and “the top 20 wine makers in the world” respectively as the main evaluation criteria of their early-stage IEOs. These founders relied on such evaluation criteria because the largest biotechnology and wine producer markets are centered in the US, Southern Europe and South America; so the targets were easily identifiable and recognizable. As well-illustrated by the founder of DNACo: “We focused on the largest conferences and trade exhibitions … our original thinking was to target the top three largest labs in the US … there were only 50 labs in the 50 US states and they all already had an older style of equipment.” This reflects the well-known recognition heuristic, where if individuals are presented with two objects to rate, and recognize only one, they will give a higher rating to the recognized object (Goldstein & Gigerenzer, 2002).

I developed the ‘no-rules rule,’ which uses no systematic structure or criteria in opportunity evaluation, by how the respondents described their approach as “embracing luck, having no strategy and being naïve” (OdorCo and BioactiveCo). The founders of OdorCo, an anti-odor chemical manufacturer, relied on the ‘no-rules’ rule in evaluating their first IEO. A few months before they founded OdorCo, they were approached by a US businessman who was looking for innovative odor control solutions for the US market. At that time, they did not have any experience or criteria upon which to evaluate the opportunity but believed that the potential US partner could sell some of the product to US consumers. This led to their early (and initial) internationalization. They also relied on simple calculus (having a pre-commitment from a foreign buyer) and the ‘fit’ rules (a match in product availability, quality and timing between two parties) and the pre-existing distribution networks of a US partner (a ‘low-cost’ solution to expand quickly with little risk). Therefore, the entrepreneurs relied on multiple rules. As an OdorCo founder commented:

I think it was just pure sheer dumb luck with us the way we have approached things [the international markets] because we weren’t following a strategy based on a Salesman 101 course. We are keeping it simple. … Just by coincidence an American businessman had come out to Australia looking for odor control and heard about us [via [an online] bulletin board system], probably via the university. So he placed an order with us … before we even named the product. We didn’t have anything [done] except the testing…. It’s really funny what happened. He’s a businessman and had an extensive distribution network in the US based on his existing business.

Emotion-Based Rules (“What Do I Feel?”)

This study found that some entrepreneurs appeared to be more emotion-driven than others in making decisions about IEOs. The use of emotion in evaluating IEOs comprises gut feelings, which is intuition-based, such as “This agent was the first person I met in China and it felt right” (ClothCo); and people-driven rule, evaluation based on personal characteristics, by being “attracted to someone’s personality” (HairCo), suggesting someone may be easy and enjoyable to work with. The role of emotion could have influenced entrepreneurs who did not plan to internationalize their businesses but encountered by chance a favorable situation or business people who they resonated with. Importantly, profit was not at the top of their agenda. A representative example of the emotion-based rule is shown by the founder of HairCo, a salon owner, who decided to start his first international franchisee when he met a businessman at a yoga retreat whom he felt good about. As HairCo’s founder described it:

I must say that I was attracted by the personality of this person [the first international franchisee, a New Zealander]. It wasn’t necessarily the dollars. I met him at a yoga retreat and we got chatting and that’s how it happened really. It was fate and I know that he had … people skills.

Action-Based Rules (“What I Can Do?”)

The data show that entrepreneurs also relied on real actions to make opportunities happen (i.e., ‘action-based’ rules) instead of waiting for IEOs to appear. The entrepreneurs who relied on these action-based rules appeared to be much more aggressive (as observed in their body language and tone during the interviews) and had lengthy entrepreneurial experience. The action-based rules comprise the ‘give-then-receive’ rule, by “giving free services so as to sell profitable products” (TelcoCo) or investing many months and sending product samples and emails to develop a conversation with foreign buyers (WaterCo) before their IEOs were actualized. Another frequently used action-based rule is the ‘exploit-then-evaluate’ rule, as exemplified by the founder of CorkCo, a new entrant in the synthetic wine cork business who acted first before making an evaluation and later used the outcome to decide which opportunities to focus on. This rule enabled him to find promising IEOs (i.e., high-performing agents) by the ‘process of elimination,’ as illustrated by his statement:

We signed up any agents who were interested in us and so once we had agents, we were pushing them to start selling. I think they [the first two foreign agents] just said “Yes we are trying very hard” but in the end they didn’t sell anywhere near enough so we had to say ‘Goodbye’. We made the change [hired a new agent] and the new guy is selling 10 times what they were selling.

Outside-Opinion-Based Rules (“What do others say?”)

Outside-opinion-based rules, or the reliance on others’ opinions, in this case, the opinion of other entrepreneurial actors in the evaluation of early-stage IEOs, also emerged. The data reveal the reliance on the ‘evaluated-by-others’ rule; for instance, as the respondents stated, “a manager of the Japanese firm watched the Davis Cup and saw we sponsored a team’s sportswear and enquired about our product” (SportCo) and “the Taiwanese supplier showed interest in being our agent” (OdorCo). Another rule, the ‘relationship-as-positive-cue,’ or treating an existing contact’s strong ties as a favorable opportunity signal; this is reflected in the narratives of our respondents, such as “one Fuji office introduced us to other Fuji offices” (ColorCo) and “our local franchisee’s brother in New Zealand was interested in us” (GrillCo). Another rule type is the leveraging others’ resources, where others’ resources are seen as a favorable opportunity signal, such as “we followed our German buyer’s route to enter the nutraceutical markets,” which revealed a new way of internationalizing (BioactiveCo).

The following illustrates how the evaluation by other actors (i.e., a new foreign supplier) positively influenced the entrepreneurs’ decision. It shows how a search for a foreign supplier (to develop a specialist product) led to a positive evaluation by the supplier, which led to a partnership in China. As the founder of ClothCo, a children’s fashion manufacturer, explained:

We had a presentation of our first [product line] of clothes. The [Chinese] manufacturer came and saw the [product line] in its entirety and was so impressed that she said that this would sell very well in China. So she approached us to go into partnership [with her] in China. It sort of fell into place because the Chinese [manufacturing] company approached us and said, “You should open a store in China.… Do you want to be a partner?” She was convinced it would sell very well, as it was a low-cost, [and had] no initial outlay.… It’s good for her because she manufactures the goods. I basically don’t have to do much, I will get a cut from the wholesaler.

Counting the Simple Rules Use

Table 3 provides the content analysis of the IEO evaluations (see also Web Appendices 4 and 5 for more details). This study finds no clear pattern in terms of the frequency and tendency to use particular types of simple rules that distinguish the knowledge-based from the non-knowledge-based sectors or the experienced vs less experienced entrepreneurs; they used all 13 simple rules. Some entrepreneurs used multiple simple rules to evaluate an IEO while others used one simple rule (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). The most observable difference is the substantially greater use of finer heuristics-based and economics-based rules in the evaluation of late-stage IEOs; these rules were not used in the early-stage IEOs – instead heuristics-, emotion-, action-based, and outside-opinion-based rules were used (to be discussed in more depth under the ‘Complex Rules’ subheading below).

The location and entry-mode decisions for early-stage IEOs across all 15 cases were based on the simple rules (see Table 3, Web Appendices 4 and 5). In terms of location decisions, no systematic and structured sequence of decision-making in foreign market selection was found (e.g., “choose foreign location first then pick the right entry mode,” or vice versa). Thus the location of internationalization was unpredictable, ranging from distant markets to culturally-similar markets. In terms of entry-mode, exporting, licensing and distributorship – essentially low-risk, low-commitment entry modes – were widely used in the cases because they are easy, not complicated (i.e., BioactiveCo, OdorCo, ColorCo, DNACo, WaterCo, SportCo), can fulfill the desire/request of the buyers/partners (i.e., OdorCo, SeaweedCo, RipeCo, SportCo, JuiceCo), and to tap the resources of buyers/partners (i.e., ColorCo, ClothCo). The reasoning behind the use of other entry modes includes letting the local experts sell quickly (i.e., master franchising model by HairCo and GrillCo; partnership by ClothCo) and match the focal firm’s business model (i.e., project-based mode for SAPCo and TelcoCo (both software developers)).

Why were the simple rules predominant in the evaluation of early-stage IEOs? Although prior knowledge of the sector (i.e., domain familiarity) did not appear to influence the IEO evaluation process, the findings reveal that entrepreneurs were influenced by time pressure to generate cash flow for survival, as they were running out of or lacking resources (i.e., SeaweedCo, BioactiveCo, WaterCo, DNACo, JuiceCo, SAPCo, TelcoCo, RipeCo, ClothCo, SportCo), or conserving resources (i.e., BioactiveCo, DNACo, WaterCo, OdorCo, ColorCo), which could have discouraged the use of the complex rules. Additionally, the entrepreneurs also admitted that they hate or do not trust market research (i.e., WaterCo, JuiceCo), and were science-, not marketing-driven – a belief in that they as scientists-turned-entrepreneurs do not follow business textbook recommendations (i.e., OdorCo). Moreover, some reported that they are specialists (producers of unique products not offered by mainstream players or unique market positioning) and therefore easily searched and evaluated by international players to which the entrepreneurs responded positively and quickly (i.e., BioactiveCo, JuiceCo, GrillCo, OdorCo, ColorCo, RipeCo, ClothCo, and SportCo) (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). For example, the founder of RipeCo, a maternity wear producer, stated that “When you’re selling a niche product … most countries don’t have that many suppliers. Like in Dubai for instance, they [an Australian woman] approached us [after fortuitously seeing their display in Queensland]. Being in a niche I think has helped [stimulate] people to have more interest in us.”

The above findings led to insights which are summarized in the following propositions:

Proposition 1:

Entrepreneurs of early internationalizing firms are more likely to use simple rules in their early-stage of internationalization.

Proposition 2:

The use of simple rules by entrepreneurs of early internationalizing firms is more likely to lead to unpredictable choice of location of internationalization, including distant and culturally similar markets, and the tendency to use low-risk and low-commitment entry modes.

Proposition 3:

The use of simple rules by entrepreneurs of early internationalizing firms is influenced by time pressure, entrepreneurs’ prior decision-making models, and the firms’ unique market positioning that enable the firms to be found by opportunities than systematically analyzing them.

Revised Rules When Evaluating Early-stage IEOs

During the first three years of internationalization, the data show that when evaluating early-stage IEOs, the entrepreneurs often made major mistakes or encountered setbacks in international markets. These experiences offer rich learning opportunities but most importantly, they allow the entrepreneurs to revise the simple rules to improve their IEO evaluation. The data reveal seven types of rules that the entrepreneurs revised that fall into three categories – externally- (“What do others help me learn?”), situation- (“Is it beyond my control?”), and internally-driven (“I wish I had known that in advance”) rules (see Table 2, Web Appendices 2, 4 and 5), described below.

Externally-Driven Rules (“What Do They Help Me Learn?”)

The externally-driven rules for the IEO evaluation include criteria based on problems caused by other players (e.g., false representations by agents) categorized into ethics and trust, commitment, and non-opportunity (Table 2). The problems forced the entrepreneurs to learn new things that they did not consider earlier in IB. The problems ended out causing significant financial losses for many firms (e.g., SeaweedCo, JuiceCo, HairCo, GrillCo, OdorCo, ColorCo, SAPCo, RipeCo, and SportCo; see Web Appendices 2, 4 and 5). These externally-driven rules include ethics and trust because some entrepreneurs were “cheated by foreign agents” (e.g., an old friend of a Taiwanese agent misrepresented himself as the agent and signed a new contract with OdorCo) or “dishonest licensees” (e.g., an Irish licensee refused to pay the license fees owed to SportsCo). They also include commitment criterion, that is avoiding those “not committed to the focal entrepreneur” (e.g., preferring potential foreign franchisees who are committed to do business together and willing to come and learn about the franchise; HairCo and GrillCo) and non-opportunity criteria, because certain markets are perceived as having an ethnocentric bias (e.g., some buyers question the quality of Australian products; SAPCo and SeaweedCo), presenting religious barriers (e.g., negative public reaction to an image of a brand perceived as obscene in a Muslim country; JuiceCo), or lazy agents (e.g., “the UK guys take our products, buried us but no one sells”; ColorCo and RipeCo). The following case described by the SportCo’s founder illustrates how new rules, added over time, such as those pertaining to ethics and trust, became important rules for the IEO evaluation as mistakes occurred that caused setbacks and substantial financial losses.

The first guy [a firm licensed to manufacture SportCo’s sportswear], got greedy so I had to then withdraw the license because he didn’t pay his license fee. Then I got another company to take over the license and … he had a partner who was a manufacturer and they had an argument 12 months into the joint venture. Everything was going alright and it was personal … he [got] involved with women or whatever and I lost the manufacturing arm. His partner was the person who had all the machines. So it nearly went under. (SportCo founder)

Situation-Driven Rules (“Is It Beyond My Control?”)

The second category of revised rules is situation-driven rules, and their criteria are temporal. These rules are driven by problems beyond the entrepreneurs’ control. These rules emerged after the entrepreneurs experienced financial or opportunity losses (e.g., SeaweedCo, BioactiveCo, CorkCo, DNACo, JuiceCo, OdorCo, ColorCo, and SAPCo; see Web Appendices 2, 4 and 5). One of the revised rules is ownership criteria which include stability in the ownership or management of foreign businesses which often affect IEOs (e.g., “the [major] licensing deal with XYZ [a multinational firm] fell off because our new management prefers a new direction,” JuiceCo; or “It went nowhere because the potential client was sold to a competitor,” DNACo). Another revised rule is performance criteria (e.g., “they [foreign agents] lost focus and didn’t sell anything,” ColorCo; “the [US] client’s son who took over the business was too busy with Ferraris and ignored us,” SeaweedCo). A representative example of these types of revised decision-making rules is the case of ColorCo, a software developer. The founder’s salesperson (a business partner who set up a separate company as a marketing arm) signed up resellers based on relationships from his 30 years in the printing industry. However he kept failing to find the right opportunities in certain foreign markets, losing the opportunity to generate international sales. As the ColorCo founder recalled:

[It] was a disaster—really useless. We were so excited in the beginning and then [the British reseller] just lost focus. So then we went to another dealer there who did nothing and then we had another dealer and another one. I think we are on to the 8th or 9th or 10th [resellers in the UK] one now.

Internally-Driven Rules (“I Wish I Had Known that in Advance”)

The third revised rule category is internally-driven rules, derived from the founders’ mistakes, some of which caused significant financial losses and even near-bankruptcy for some entrepreneurs (e.g., OdorCo, SAPCo, TelcoCo, and WaterCo; see Web Appendices 2, 4 and 5). These rules emerged from the entrepreneurs’ utter ignorance of what they were supposed to know to do IB successfully. These include marketing and planning criteria (e.g., “We didn’t know what we could say or couldn’t say” when marketing and labelling chemicals in international markets, OdorCo; “we felt naïve about this first foray [into Europe] and said we’d better re-think, re-plan and be a lot more patient,” SAPCo). The other revised rules also included logistics criteria (e.g., “we should have used a [local] reseller,” TelcoCo; “We mismanaged [the manpower and client servicing], it nearly put us out of business,” WaterCo). The case of TelcoCo, a software developer, illustrates how internally-driven rules changed how some entrepreneurs evaluated IEOs into the future. In the first three years of operation, the TelcoCo founder and his engineers realized that they lacked international logistics and operations knowledge (e.g., contract knowledge, the effects of time differences on service operations, failure to have their own employees at the client site) when servicing a large Hong Kong client. This resulted in near-bankruptcy. The setbacks enabled the founder to revise the rules for IEO evaluation and in turn, this enabled the firm to recover and successfully establish itself several years later. As TelcoCo’s founder stated:

We should have had local support on the ground—we lost day-to-day contact with the client and little problems were not resolved quickly enough. So we ended up with an unhappy client. You really need to be on the ground with local teams there to just smooth out some of those teething problems and work through them and we didn’t do that. So we learned our lesson.… So now we sign a Teaming Agreement on an opportunity-by-opportunity basis.

Counting the Revised Rules Use

A content analysis of the revised decision-making rules from the early-stage IEOs until the initial years of internationalization reveals that externally-driven rules develop with higher frequency than the situation- and internally-driven rules (see Table 3, and Web Appendices 4 and 5 for more detail). This may reflect the founders’ inability to control problems caused by other actors and illustrate why feedback and lessons learned from business interactions can help the founders improve their IEO evaluation. Overall, 11 out of the 15 firms had low-level firm performance in the early stage of internationalization. Those that had medium-level performance (e.g., CorkCo, JuiceCo, GrillCo, HairCo) were assisted by the relatively large domestic market demand compared to those that were more and fully dependent on international markets (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). These show that, for entrepreneurs of early internationalizing firms, the initial years of internationalization is more about learning about IEOs rather than ‘building wealth or making a lot of profit’ and a desire to improved decision-making rules for future success. In this IEO learning process, the entrepreneurs often stumble and face problems that they cannot control and cannot know of earlier leading to suboptimal selection of IEOs and eventually unfavorable firm performance. This insight led to the next proposition:

Proposition 4:

Entrepreneurs’ ability to revise opportunity evaluation rules during firm internationalization is more likely to lead to better selection of future opportunities.

Complex Rules When Evaluating Late-Stage IEOs

Turning to late-stage IEOs, the cross-case findings reveal that entrepreneurs’ evaluation of late-stage IEOs relies on nine types of rules categorized as finer heuristics-based (“Which option is better for us?”) and economics-based (“Which option is the best for us?”) rules (see Tables 2–3 and Web Appendices 3–5 for more detail), described below. However, for some cases, entrepreneurs use simple rules such as the outside-opinion-based rule (e.g., being approached by other entrepreneurial actors for their expertise) albeit in a more discerning way (“Carefully scrutinize what others say”). As shown below, many of these complex rules resemble the optimization and calculative logic used in the Economics model of internationalization.

Finer Heuristics-Based Rules (“Which Option is Better for Us?”)

The finer heuristics-based rules are refinements of the rules learned in a current venture; they are essentially more strategic than the simple rules (see Web Appendix 3 and Tables 2–3). The first of the three types of finer heuristics-based rules is the learned-and-tested rule, a rule that has passed ‘the test of time’ across multiple IEOs. This rule helped entrepreneurs to recognize ‘possible’ vs ‘unlikely’ IEOs. It reflects the entrepreneurs’ mental model about IEOs. As a consequence of this rule use, six of the 15 entrepreneurs found highly promising IEOs (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). For instance, after a decade of internationalization and five major setbacks with IB activities, the founder of ColorCo found the rule of ‘two distributors per country’ the most efficient approach to internationalization because it creates competition and therefore boosts the distributors’ motivation to sell more. The founder of WaterCo, a producer of branded mineral water, illustrates this rule. He initially used ‘simple’ rules (i.e., ‘give-then-receive’ and ‘good fit’) to evaluate early-stage IEOs, but after five years of internationalization, and after confronting buyers for their lack of commitment and high logistics costs, he developed a more precise and effective rule to assess late-stage IEOs:

I will do quick calculations saying, “Well there has got to be a 50% margin for the retailer, 30% margin for the distributor…” I do a quick conversion of your cost price … and I have a simple spreadsheet that I just plug those figures into and I can tell you whether I’m going to do business or not, whether we can be competitive against Evian, etcetera.

There are two other types of finer heuristics-based rules: ‘leveraging contingencies’ and ‘strategic fit’. The ‘leveraging contingencies’ rule is more calculative than the simple rules because the entrepreneurs, over time, become more knowledgeable about the ‘possible’ vs ‘unlikely’ IEOs. The ‘strategic fit’ rule is also more calculative than the ‘fit rule’ as the entrepreneurs emphasize the strategic match (e.g., products, business model, supply chain, firm size, and priority) between existing and new IEOs. One example is TelcoCo, a software developer, whose CEO realized that an optimal approach would be to partner with smaller firms that prioritized his firm’s needs because earlier, a large global consulting firm had locked them out from partnering with other firms. These rules helped nine of the 15 entrepreneurs to identify highly promising IEOs (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). A good example of the ‘more calculative leveraging contingency’ rule comes from OdorCo, the odor chemical manufacturer. After 15 years of internationalization, and after confronting several dishonest foreign agents, which led to lawsuits, its founders stated that their late-stage IEOs emerged from careful evaluation of unsolicited inquiries from overseas to ensure that only honest and capable agents were hired and that they strategically developed only existing IEOs because the existing agents had already proven their honesty and capability. As the OdorCo founder explains:

We no longer signed up anyone who found us [on Google] after all the mistakes we made. We have to be very careful [now] … there are many dishonest and horrible people … so finding the right agents takes time.… It’s easier to work with those we already know.

Outside-Opinion-Based Rule (“Carefully Scrutinize What Others Say”)

The data also reveal that nine of the 15 entrepreneurs used the outside-opinion-based rule – when approached (e.g., for a partnership) by a foreign firm based on these firm’s positive reputation, credibility, expertise, and/or specialty, do a thorough assessment of the outside fir – as an evaluation approach in late-stage IEOs (see Table 3, and Web Appendices 4 and 5). Although the outside-opinion-based rule can take place in late-stage IEO evaluation, the founders tend to be “more discerning” in responding to such opportunities compared with early-stage IEOs. SeaweedCo, a manufacturer of seaweed-based medicinal products, illustrates this rule. After internationalizing for five years and recognizing that it had a special advantage in selling seaweed as medical ingredients in the US and Japan, the SeaweedCo founder agreed to partner with a Canadian pharmaceutical company that approached them and offered a large, long-term contract manufacturing business:

The way we extract our GFS [a chemical element from seaweed] compound is [by] using a proprietary … process that retains the natural properties of [the seaweed], while competitors use solvents in their processes to extract it. That’s a big advantage [for us].… They [a large Canadian buyer] picked us and we had never even heard of them … it was a large, 15-year contract to develop the ingredients.

Economics-Based Rules (“Which Option is Best for Us?”)

Use of economics-based rules is the most explicit distinction between late- vs early-stage IEO evaluation across the cases. Twelve out of the 15 late-stage IEO evaluation cases used systematic and economically driven rules (see Tables 2, 3 and Web Appendices 3–5). As a consequence of the use of these rules, eight entrepreneurs found highly promising IEOs and four found promising IEOs (see Web Appendices 4 and 5). The data reveal six types of economics-based rules: complex calculus, ideal opportunity, large scale IEO search, large scale IEO development, efficiency and resource seeking, and long-term commitment rules (see Tables 2, 3). These rules all focus on identifying the best IB opportunity out of many opportunities that the entrepreneurs had exploited in the current venture. I discuss the most representative examples of economics-based rules below.

The ‘complex calculus’ rule requires the use of a more calculative approach to evaluating IEOs such as using business plans, conducting market research, analyzing multiple criteria, performing cost–benefit analyses, and identifying large IEOs and well-known foreign businesses in order to increase revenues. RipeCo, a maternity fashionwear manufacturer, offers an example of how the ‘complex calculus’ rule was used to evaluate a late-stage IEO. In its first internationalization to the Middle East, the founders of RipeCo relied on the ‘no-rules’ rule (e.g., “we pursued whichever opportunities that came first”) to export their maternity fashionwear, after an Australian mother from Dubai inadvertently found RipeCo in a department store in Brisbane. In contrast, after five years of internationalizing, RipeCo founders evaluated IEOs in a remarkably different way, relying on the complex calculus rule; they conducted market research and cost–benefit analysis as described by RipeCo’s founder:

After our entry into the US and the difficulties we [had] faced [earlier in the UK, Ireland, New Zealand], we became a quite serious exporter, so from that time [onwards] everything was different. Every time you enter a market now [you must be] much more calculating [about cost and benefits] and [do] a lot more research [on market demand, competition, logistics]. And we … have to weigh all of the other things when going into that market. We are quite strategic about new markets.

The ‘ideal-opportunity rule’ pertains to a type of opportunity that enables accelerated firm growth for revenue and cash flow. This is another type of economics-based rule. In late-stage evaluation, as a result of accumulated learning and an ability to distinguish possible vs unlikely IEOs, many of the entrepreneurs had recognized the ‘ideal’ opportunity – one that ultimately enabled them to become more economically driven in choosing IEOs. An example of this rule is ColorCo, the software developer, whose founder learned that being an OEM (original equipment manufacturer) for large multinational firms is a fruitful route for development and growth as it requires few resources and almost guarantees strong sales. ColorCo founder learned this after a decade of actively pursuing many IEOs (and making plenty of mistakes), as illustrated below:

Find more OEMs because it’s an easy way to grow, you don’t need any more staff, you don’t need any more people, it’s like you buy that company, it becomes yours and they sell your product. But because it’s got their name and once someone is an OEM they have to buy huge amounts from you each time and then they sell them. We discovered that recently.