Abstract

We introduce the topic of this Special Issue on the “Role of Financial and Legal Institutions in International Governance”, with a particular emphasis on a notion of “international mobility of corporate governance”. Our discussion places the Special Issue at the intersection of law, finance, and international business, with a focus on the contexts of foreign investors and directors. Country-level legal and regulatory institutions facilitate foreign ownership, foreign directors, raising external financial capital, and international M&A activity. The interplay between the impact of foreign ownership and foreign directors on firm governance and performance depends on international differences in formal/regulatory institutions. In addition to legal conditions, informal institutions such as political connections also shape the economic value of foreign ownership and foreign directors. We highlight key papers in the literature, provide an overview of the new papers in this Special Issue, and offer suggestions for future research.

Résumé

Nous introduisons le sujet de ce numéro thématique sur le “Rôle des institutions financières et légales dans la gouvernance internationale” avec un accent particulier sur la notion de “mobilité internationale de la gouvernance d’entreprise”. Notre discussion place le numéro thématique à l’intersection du droit, de la finance et de l’international business, avec un focus sur les contextes des investisseurs et des directeurs étrangers. Les institutions légales et réglementaires au niveau des pays facilitent la propriété étrangère, la nomination de directeurs étrangers, la levée de capitaux financiers externes et l’activité de F&A internationales. L’interaction entre l’impact de la propriété étrangère et les directeurs étrangers sur la gouvernance d’entreprise et la performance dépend des différences internationales dans les institutions formelles/réglementaires. En plus des conditions légales, les institutions informelles telles que les connexions politiques façonnent aussi la valeur économique de la propriété étrangère et des directeurs étrangers. Nous mettons en lumière les textes de référence dans la littérature, nous proposons une vue d’ensemble des nouveaux textes dans ce numéro thématique, et nous offrons des suggestions pour la recherche future.

Resumen

Presentamos el tema de esta Edición Especial sobre “el rol de las instituciones financieras y legales en la gobernanza internacional” con un énfasis particular a la noción de “la movilidad internacional en la gobernanza corporativa”. Nuestra discusión pone esta Edición Especial en la intersección entre el derecho, las finanzas, y los negocios internacionales, con un enfoque en los contextos de los inversionistas y los directores extranjeros. Las instituciones legales y regulatorias a nivel nacional facilitan la propiedad internacional extranjera, los directores extranjeros, la obtención de capital extranjero externo, y la actividad internacional de fusiones y adquisiciones. La interacción entre el impacto de la propiedad extranjera y los directores internacionales en la gobernanza y el rendimiento de la empresa depende de las diferencias internacionales en las instituciones formales/regulatorias. Además de las condiciones legales, las instituciones informales como las conexiones políticas también determinan el valor económico de la propiedad extranjera y los directores extranjeros. Destacamos artículos clave en la literatura, damos una perspectiva de los nuevos artículos en esta Edición Especial y ofrecemos sugerencias para futuras investigaciones.

Resumo

Apresentamos o tema desta Edição Especial sobre o “Papel das Instituições Financeiras e Jurídicas na Governança Internacional”, com uma particular ênfase na noção de “mobilidade internacional da governança corporativa”. Nossa discussão coloca a Edição Especial no cruzamento entre direito, finanças e negócios internacionais, com foco nos contextos de investidores estrangeiros e conselheiros. Instituições legais e reguladoras nacionais favorecem a propriedade estrangeira, conselheiros estrangeiros, levantando capital financeiro externo e atividades internacionais de fusões e aquisições. A interação entre o impacto da propriedade estrangeira e conselheiros estrangeiros sobre a governança e o desempenho das empresas depende das diferenças internacionais nas instituições formais/regulatórias. Além das condições legais, instituições informais como conexões políticas também moldam o valor econômico da propriedade estrangeira e conselheiros estrangeiros. Destacamos artigos chave na literatura, fornecemos uma visão geral dos novos artigos nesta Edição Especial e oferecemos sugestões para pesquisas futuras.

概要

我们推出本特刊主题“国际治理的金融和法律制度的作用”,并特别强调“公司治理的国际流动性”的概念。我们的讨论将本特刊放置于法律、金融和国际商务的交汇处,关注点是外国投资者和董事的情境。国家层面的法律和监管制度促进外国所有权、外籍董事、外部融资和国际并购活动。外国所有权和外国董事对公司治理和业绩的影响之间的相互作用取决于正式/监管制度的国际差异。除了法定条件之外,非正式制度如政治关系也塑造外国所有权和外国董事的经济价值。我们突出文献里的重要论文,提供此特刊新论文的概述,并为今后的研究提出建议。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

International Business (IB), economics and finance scholars have developed a significant body of research focused on the international mobility of capital, labor and goods. Two main theoretical approaches to international business strategy – internalization theory and the resource-based view (RBV) – assume that the most efficient firm strategy will be that which maximizes rents from the firm-specific assets and thus maximizes the long-run value of the firm. The role of management in such theories is essentially to identify and implement this efficient strategy. Organizational control processes are equally important in terms of creating value in the context of globalization. These processes facilitate accountability, monitoring and trust within and outside of the firm, and should ultimately lead to improvements in the firm’s performance and long-term survival.

Although prior IB and international finance studies have identified a number of governance factors that may affect global strategy both at the headquarter and subsidiary levels of a multinational company (MNC), this research generally considers corporate governance functions and processes as being location-specific (Filatotchev & Wright, 2011). The underlying assumption in the vast majority of governance papers in the context of globalization is that governance is immobile, and various governance mechanism are location-bound unlike international flows of factors of production, goods and services that form a core research area of IB. The focus in traditional international business has been on labor, capital, and goods, as well as the control processes around these inputs. Common control and governance processes facilitate trust within and outside of a firm. In a repeated game, trust plays a role that limits defections. Ownership or foreign direct investment (FDI) in an international business context is the key to creating a repeated game. Therefore FDI may facilitate the creation of trust through the overseas extension of governance practices.

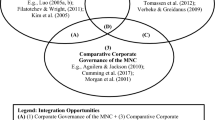

Corporate governance research from an IB perspective has traditionally not considered the mobility of corporate governance. However, there is a growing body of theoretical and empirical evidence pointing out that corporate governance structures and processes are becoming increasingly mobile internationally. Mobility of corporate governance in this context refers to scenarios where firms export or import governance practices in the process of internationalization. For example, a firm may export its governance practices to its acquisition target in an overseas location. Likewise, a local firm may import overseas governance practices by appointing foreign directors on its board or attracting foreign investors through a cross-listing on a foreign exchange. In this introduction, we focus on four related channels through which corporate governance may be internationally mobile and highlight the contributions of the papers in this Special Issue: (1) international mergers and acquisitions (Ellis, Moeller, Schlingemann, & Stulz, 2017; Renneboog, Szilagyi, & Vansteenkiste, 2017), (2) foreign ownership (Aguilera, Desender, López-Puertas, & Lee, 2017; Calluzzo, Dong, & Godsell, 2017), (3) foreign political connections (Sojli & Tham, 2017), and (4) foreign directors (Miletkov, Poulsen, & Wintoki, 2017). Overall, the recognition of corporate governance mobility presents an important opportunity for further theory building in the contest of both IB and finance research, and this is a focal point of this Special Issue.

Further, we build on an established tradition in the IB and finance areas focused on the role of formal and informal institutions and show that the mobility of corporate governance is strongly associated with diverse institutional contexts within firms operate domestically and globally. As Bell, Filatotchev, & Aguilera (2014) argue, firms are embedded in different national institutional systems, and they experience divergent degrees of internal and external pressures to implement a range of governance mechanisms that are deemed efficient in a specific national context. Therefore we suggest that formal institutional factors such as legal or regulatory, as well as informal (cognitive and cultural) institutions may shape the process of governance mobility. Likewise important is that cross-national institutional differences may pose a barrier for an international transfer of governance practices.

The ideas of mobile governance in different institutional contexts form a theoretical foundation for the papers included in this Special Issue. The call for papers for this Special Issue drew 84 submissions written by authors stemming from 24 nations. Thirteen papers were accepted for a paper development workshop in London in February 2016, and six of those papers appear in this Special Issue (an additional three appear in regular JIBS issues). Taken together, these papers provide a novel contribution to IB research by focusing on international dimensions of corporate governance mobility and the implications of macro-level, institutional factors on the governance processes and outcomes across national borders.

This introduction to the Special Issue is organized as follows. The next section discusses institutional aspects of corporate governance. The section thereafter discusses the mobility of corporate governance. We then introduce the specific topics pertaining to mobility in the case of international mergers and acquisitions, foreign owners, and foreign directors. We provide evidence of the growing importance of these topics in relation to more traditional topics in international business. The last section offers concluding remarks and suggestions for further research.

Institutional Aspects of Governance

In their seminal review of corporate governance research, Shleifer & Vishny (1997 p. 773) provide the following definition of corporate governance: “Corporate governance deals with the agency problem: the separation of management and finance. The fundamental question of corporate governance is how to assure financiers that they get a return on their financial investment.” As corporate governance research has evolved, studies have broadened the definition of “good governance” by considering it as a process-driven function that facilitates value creation. These processes develop over time across countries and within firms. The financial impact of good governance on the firm is unambiguously positive, both in terms of short-term efficiency outcomes and longer-term sustainability of the business. Perhaps most intuitive is that good governance, which minimizes the chance of managerial tunneling – defined by Johnson, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer (2000) as the expropriation of corporate assets or profits – leads to an enhanced capability of the firm to raise external capital (Aggarwal, Klapper, & Wysocki, 2005). Gompers, Ishii, & Metrick (2003) and Bebchuk, Cohen, & Ferrell (2009) provide important metrics for the robustness of governance at the firm level and find that good governance firms have higher firm value, profits, and sales growth. The finance literature also suggests that good governance leads to an increase in Tobin’s Q (Daines, 2001) and higher firm value in M&A (Cremers & Nair, 2005), among other factors. The drivers of “good governance” and its financial benefits can come from monitoring by the Board of Directors (see, e.g., Huson, Parrino, & Starks, 2001), institutional investors (see, e.g., Li, Moshirian, Pham, & Zein, 2006), creditors (Nini, Smith, & Sufi, 2012), whistle blowers (Dyck, Morse, & Zingales, 2010) and the market for corporate control (Masulis, Wang, & Xie, 2012).

Management and IB perspectives have further broadened research on “good corporate governance” by considering different organizational and institutional contexts as well as their effects on the firm’s internationalization. Some studies, for example, indicate that monitoring, though important, is not the only function of corporate governance. Indeed, good governance can also be viewed as having top managerial competency (Kor, 2003) or investment in firm-specific human capital that can enhance the quality of decision-making (Mahoney & Kor, 2015). Governance is particularly important to firms in less competitive industries (Giroud & Mueller, 2011) or in family-controlled firms (Anderson & Reeb, 2004). Importantly, good governance provides legitimacy to managerial actions (Lipton & Lorsch, 1992; Aguilera & Jackson, 2003) such that investors feel protected from management consuming private benefits of control. The extent of this legitimacy can differ across countries depending on laws, culture and levels of corruption (Judge, Douglas, & Kutan, 2008).

A growing number of studies suggest that firm-level governance mechanisms are institutionally embedded (e.g., Aguilera & Jackson, 2003; Bell et al., 2014; McCahery, Sautner, & Starks, 2017), and their functioning as well as organizational impact may be different, even in country settings that appear similar legally. This leads to two significant extensions of previous research based on a universalistic agency framework. First, governance problems at the firm level are not universal; they may differ depending on the firm’s institutional environment. Second, the effectiveness of governance remedies aimed at mitigating agency conflicts may depend on formal and informal institutions. “Law and finance” research has made the first inroads into exploring how national settings may lead to different firm-level governance models around the world.

In seminal papers, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny (1997, 1998, 2000) and La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Pop-Eleches, & Shleifer (2004) suggest that legal origin is influential in a nation’s protection of outside investors (investors other than management or controlling shareholders), which the authors suggest is largely the purpose of corporate governance. Though legal tradition (“common law” and “civil law”) succeeds in explaining many cross-sectional differences in corporate finance, critics argue that these broad categories belie the true complexity of a nation’s legal system. The US and UK economies serve as a good example. While both countries belong to the same “Anglo-Saxon” model of corporate governance, describing their legal environment solely as common law ignores differences in formal and informal “rules of the game” that may significantly impact the forms and efficacy of corporate governance mechanisms in the two countries. Consistent with this notion, Short & Keasey (1999) suggest that managers in the UK become entrenched at higher ownership levels than managers in the US. They attribute this difference to better monitoring and fewer firm-level takeover defenses in the UK. Bruton et al. (2010) and Cumming & Walz (2010) show that performance outcomes of ownership concentration and retained ownership by private equity investors may differ depending on the legal system and institutional characteristics of the private equity industry in a specific country.

Characteristics of Boards of Directors, such as goals, structure and representation may likewise be expected to differ across institutional contexts, even within broad institutional categories. Wymeersch (1998), for example, finds that in some countries, the law does not specifically dictate the role of the board of directors, so its priorities may well differ from the typical shareholder wealth maximization. Regarding board structure, some jurisdictions have two-tier boards while others have unitary boards. Rose (2005) suggests that the unitary (or one-tier) boards are typically from common law nations and two-tier boards predominate in civil law nations, however, Danish firms have adopted aspects of both. Moreover, O’Hare (2003) suggests that there may be an increase in oversight if firms with unitary systems change to a two-tier structure. Regarding representation on boards, nations differ with regard to their take on the wisdom of including directors that are insiders versus outsiders (Adams & Ferreira, 2007) as well as local versus global (Masulis et al., 2012).

A large literature, much of it in the accounting field, suggests that information environment, which includes the extent of corporate disclosure, reporting standards, the reliability of financial reporting, etc., is important to corporate governance (Bushman, Piotroski, & Smith, 2004; Leuz & Wysocki, 2016). Corporate disclosure of information through publicly accessible accounting statements serves to enhance investor trust (Bushman & Smith, 2001). Much of this literature examines the use of financial accounting in managerial incentive contracts. This research has been examined in the context of takeovers (Palepu, 1986), boards of directors (Anderson et al., 2004), shareholder litigation (Skinner, 1994) and debt contracts (Smith & Warner, 1979). The worldwide adoption of International Financial Reporting Standards has been an important development in this literature and has motivated research in this area. The positive impact of enhancing reporting standards around the globe is arguably evidence consistent with the notion that disclosure is an important mechanism in corporate governance.

Related to both the finance and accounting literature, the legal structure in a nation plays a central role in corporate governance of firms. Though firms may adapt to poor legal environments individually (Coase, 1960), research suggests that regulation leads firms to develop good governance. Mandatory disclosure can serve to reveal the true quality of a firm overall, and even managers at that firm (Wang, 2010). Firms can opt into regulatory environments by bonding to external legal environments that enhance legal requirements (e.g., with cross-listing) or opt out through going private, delisting or even foreign incorporation. Much of this literature examines changes in regulation in the US such as Regulation Fair Disclosure and Sarbanes–Oxley, but there are some international studies, such as Leuz, Nanda, & Wysocki (2003) and Dyck & Zingales (2004) that corroborate the positive association between corporate governance and a legal system that mandates disclosure. Some studies highlight the costs of regulation, both direct and indirect (e.g., Coates & Srinivasan, 2014), suggesting that the mandatory nature of disclosure is not as straightforward as its relation to corporate governance might imply.

To summarize, prior law, economics, finance and IB studies not only explore efficiency and effectiveness of various governance practices, but also identify significant national differences in how these practices are implemented at the firm level. In the following sections, we take this collective body of research a step further and discuss how national differences may facilitate or create barriers for the mobility of governance practices across national borders.

Mobility of Governance

An integration of the mainstream IB research with institutional theory from finance, law and economics, provides new interesting dimensions to the discussion of corporate governance mobility. Traditional IB studies have identified how different forms of institutional distance may affect the way MNCs tap into international factors markets and develop their strategies in terms of global diversification of their product and services (Brouthers, 2002; Tihanyi, Griffith, & Russell, 2005). What is not clear, however, is how these institutional factors may affect the exporting of governance and its implications.

Given the predominant focus in extant literature on internal, organizational aspects of corporate governance, there is limited prior work on potential roles of the firm’s institutional environments in terms of their impact on the link between governance factors, international business strategy and ultimately performance. Aguilera & Jackson (2003), for example, suggest that because business organizations are embedded in different national institutional systems, they will experience divergent degrees of internal and external pressures to implement a range of governance mechanisms that are deemed efficient in a specific national context. Therefore contrary to the universalistic predictions of agency-grounded research, different social, political and historic macro-factors may lead to the institutionalization of very different views of firms’ role in society as well as what strategic actions and their outcomes should be considered as acceptable.

More recent sociology-grounded research suggests that governance is a product not only of coordinative demands imposed by market efficiency, but also of rationalized norms legitimizing the adoption of appropriate governance practices (Bell et al., 2014). Legitimacy is the “generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate, within some socially- constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, 1995, p. 574). This perspective focuses less attention on the individual efficiency outcomes of structural governance characteristics that are at the core of agency perspective, and instead concentrates more on theoretical efforts to understand how governance mechanisms affect the firm’s legitimacy through perceptions of external assessors, or the stakeholder “audiences”.

Research within institutional theory and social psychology fields differentiates between various types of legitimacy judgments that include, in addition to instrumental (pragmatic), also cognitive and moral dimensions. More specifically, institutional theorists predict that regulative, normative and cognitive institutions put pressure on firms to compete for resources on the basis of economic efficiency. However, institutional pressures may also compel firms to conform to expected social behavior and demands of a wider body of stakeholders. In other words, the ability of organization to achieve social acceptance will depend on, in addition to efficiency concerns, the ability of its governance systems to commit to stewardship management practices, stakeholders’ interests, and societal expectations.

These theoretical arguments may have far-reaching implications for corporate governance in an IB context. First, the firm’s quest for legitimacy may lead to changes in its corporate governance practices and processes. For example, some firms, in addition to enhancing the monitoring capacity of boards, may also incorporate stakeholder engagement mechanisms into their formal governance structures by assigning responsibility for sustainability to the board and forming a separate board committee for sustainability. Consistent with this notion, the co-determination system of corporate boards in Germany ensures that representatives of key stakeholders, including employees, have a direct say in governance matters. A system of remuneration that involves not only financial performance benchmarks, but also factors associated with longer-term sustainability may be another governance factor contributing to moral legitimacy. Similarly, some companies introduce wider performance criteria and definitions of risk in their risk-movement systems that use non-financial indicators. Therefore unlike studies in finance, economics, and strategy fields, institutional framework considers corporate governance as an endogenous, socially-embedded mechanism that may be highly responsive to various legitimacy pressures (Filatotchev & Nakajima, 2014).

These arguments shed new light on our notion of internationally mobile corporate governance by suggesting that firms may adjust their governance mechanisms strategically when venturing into overseas factor and product markets. For example, Moore, Bell, Filatotchev, & Rasheed (2012) advance a comparative institutional perspective to explain capital market choice by firms going public via initial public offering (IPO) in a foreign market. Based on a sample of 103 US and 99 UK foreign IPOs during the period 2002–2006, they find that internal governance characteristics (founder-CEO, executive incentives, and board independence) and external network characteristics (prestigious underwriters, degree of venture capitalist syndication, and board interlocks) are significant predictors of foreign capital market choice by foreign IPO firms. Their results suggest foreign IPO firms select a host market where its governance characteristics and third party affiliations fit the host market’s institutional environment. The basis for evaluating such fit is the extent to which isomorphic pressures exist for firm attributes and characteristics to meet legitimacy standards in host markets. Thus differences in internal governance characteristics and external ties are associated with strategic capital market choices such that an increased fit results in a higher likelihood of choosing one market over another. In other words, when firms select between different stock markets for their foreign IPO, they try to “import” governance standards that they perceive as more legitimate by investors in a specific market. These findings are particularly important given that Syvrud, Knill, Jens, & Colak (2012) find that, on average, foreign IPOs result in less proceeds.

Further, research by Bell et al. (2014) focuses on legitimacy in the stock market, where investor perceptions of the foreign IPO firm’s overall legitimacy fall at the intersection of the cognitive and regulatory institutional domains. These domains are aligned with the firms’ governance bundle and its home country legal environment, respectively. IPO firms originating from countries with institutional environments granting weak minority shareholder protections, such as China or Russia, will have to adopt a larger number of governance practices to gain the same level of legitimacy as IPOs from strong governance jurisdictions. This international mobility of firm- and macro-level governance factors can go both ways.

In a more recent paper, Krause, Filatotchev, & Bruton (2016) observe that institutional characteristics of foreign product markets influence the structure of boards of directors of US firms active in these markets. They argue that allocating greater, outwardly visible power to the CEO will build the firm’s legitimacy among customers who are culturally more comfortable with high levels of power distance. Scholars rarely conceptualize boards as tools firms can use to manage product markets’ demand-side uncertainty, but the results of this study suggest they should. Further, existing research in comparative corporate governance (e.g., Aguilera & Jackson, 2003) has argued that national institutions affect firm-level governance mechanisms, but this research also focuses almost exclusively on home country institutions. Clearly, institutional characteristics of foreign product markets can also have an effect on a firm’s governance, even if the firm is incorporated and headquartered in the United States.

To summarize, the legitimacy perspective suggests novel dimensions to the notion of corporate governance mobility. From the agency perspective, MNCs may export/import corporate governance to obtain access to superior resources and achieve efficiency outcomes. For example, by importing foreign directors, firms in emerging markets can gain access to enhanced managerial expertise and monitoring capabilities that may help them to be more competitive in an international market (Giannetti, Liao, & Yu, 2015). In addition, from an institutional perspective, MNCs may adjust their governance systems to adhere to expectations and governance standards in a foreign product and factor markets, and therefore increase their legitimacy among local stakeholders, including investors and customers. These two perspectives differentiating between efficiency and legitimacy are not orthogonal, and the extent of governance mobility is determined by a complex interplay of firm- and industry-level factors, as well as financial, legal and cognitive institutions in the home and host countries.

Institutional factors may also create significant barriers for corporate governance mobility. In terms of formal institutions, differences in national governance regulations may impede a transfer of governance practices across national borders. For example, until recently the Chinese government imposed restrictions on foreign ownership of local companies that had a limiting effect on how much influence Western institutional investors may have when deciding on various governance matters. Differences in informal institutions, such as culture, may also create barriers for the transfer of governance when, for example, imported governance practices are not considered locally as legitimate. Cultural differences influence governance not only directly, but also indirectly through its influence over time in shaping institutions. For example, culture can influence governance and other managerial decision-making through beliefs or values that influence individual agents’ perceptions, preferences, and behaviors. As a result, culture ultimately affects the utilities of agent’s choices, both at the individual level and-as frictions are always present-at the firm and national levels, when local players may have difficulties adopting best governance practices due to behavioral and cognitive biases. Culture also affects governance and managerial decision-making by influencing national institutions, which can be viewed as a path-dependent result of cultural influences and historical events (David, 1994). Recent examples surround governance tensions in Japan, China and other South-East Asia economies between local investors on one hand, and foreign board members and CEOs coming from the Western economies, indicating that cultural differences may create barriers for the transfer of “good governance” concepts that local participants in corporate governance mechanisms find difficult to accept. Although our emphasis here was on how institutional factors may facilitate the transfer of corporate governance, institutional barriers to this transfer represent an important but relatively less explored area.

Specific Modes of Transferring Governance

If the firm-level corporate governance structures and their organizational outcomes in terms of strategies and performance are institutionally embedded, then the extent of governance mobility as well as its effects on exporting/receiving firms is far from universal. They may depend on institutional differences in home/host locations. Exactly how institutional factors affect the mobility of corporate governance and its implications depends on firm-level corporate governance, the mode(s) in which corporate governance is transferred, and the institutional environments from and to which governance is transferred.

The mobility of governance depends on the mechanisms used partly because there is differential evidence on the extent to which governance can be learned, copied, or imitated. Consistent with this notion, Doidge, Karolyi, & Stulz (2007) find significant heterogeneity in firm-level corporate governance within countries. Prior research has shown that investors themselves learn about the value of governance, and as such the returns to investment based on governance disappear over time. Indeed, Subramanian (2004) shows that the advantages to incorporating in Delaware differ across small versus large firms and disappear over time (counter to Daines, 2001). Bebchuk, Cohen, & Wang (2013) show that the value of the Gompers et al. (2003) governance index in predicting stock returns over time disappears as investors learn about the value of such governance; that is, the price of well governed stocks goes up and the returns go down. Nevertheless, while investors appear to learn about the value of governance, it is difficult for some firms to observe, learn, and adopt best practices in governance due to differences in internal process of the firm, behavioral and cognitive biases which limit the ability to copy well (Amin & Cohendet, 2000; Klapper & Love, 2004). Learning is local, requires skill acquisition, acclimation to the right mindset, interactions with the right people, and a thirst for external reputation. Also, learning requires overcoming bad governance. For example, Romano (2005) suggests that there are mistakes made by policymakers when they adopt minimum governance standards. Policy implications on governance standards is a partisan topic, however. Involved in these policies are two controversial topics: globalization versus nationalization, and government involvement in the corporate world. The law and economics/finance literature is fairly consistent in their conclusion that legal institutions, both public and private (La Porta et al., 2006; Jackson & Roe, 2009; Cumming, Knill, & Richardson, 2015), are good for firm access to capital and financial development in general. Consistent with this notion, policymakers who find this research compelling should support legislation supporting the exporting or importing of good corporate governance, especially in nations where legal institutions are lacking.

At the same time, fairly recent events, such as the Great Recession, “Brexit” in the UK and an increase in the popularity of nationalism among citizens in some nations have moved some policymakers to take a more protective stance with regard to foreign ownership. As international trade and capital flows contract, the International Monetary Fund acknowledges that globalization is not without risks. Taking into consideration both of these trends, it is difficult to discuss with any specificity global policy implications.

In this Special Issue, the papers comprise analyses of four types of international transfer of corporate governance: international M&As (Ellis et al., 2017; Renneboog et al., 2017), foreign investors (Aguilera et al., 2017; Calluzzo et al., 2017, foreign political connections (Sojli & Tham, 2017) and foreign directors (Miletkov et al., 2017).

The popularity of the international M&A literature has been growing markedly over time. Figure 1 shows that articles that reference international business in general have declined over time relative to articles that reference international acquisitions, shareholder rights, and creditor rights. Some key papers in the literature on international M&As and related topics of loans and creditor rights are summarized in Table 1. Esty & Megginson (2003), Bae & Goyal (2009), Haselmann, Pistor, & Vig (2010), Cumming, Lopez-de-Silanes, McCahery, & Schwienbacher (2015), and Qi, Roth, & Wald (2017) show that loan structures and debt tranching depend significantly on creditor rights and shareholder rights. In turn, international M&As, which are often financed with significant leverage, depend on access to debt finance and international levels of creditor and investor protection. Bris & Cabolis (2008) and Martynova & Renneboog (2008) find evidence that the cross border mergers have a higher impact on target firms share prices in countries with better investor protection, and when the target is from a country of better investor protection. In the context of leveraged buyouts (LOBs), however, Cao, Cumming, & Qian (2014) find evidence that cross-border LBOs are more common from strong creditor rights countries to weak creditor rights countries. Further, LBO premiums are lower in countries with stronger creditor rights and lower among cross-border deals. Cao, Cumming, Goh, & Qian (2015) show that the impact of country-level investor protection on deal premiums is stronger for LBO than non-LBO transactions.

Google Scholar hits on international acquisitions, creditor rights, and related topics. This figure displays the number of Google Scholar hits as a percentage of the hits in 2008 for different search terms: Acquisitions (54,100 hits in 2008), International Acquisitions (290 in 2008), Creditor Rights (835 in 2008), Shareholder Rights (1380 in 2008), Shell Companies (288 in 2008), and International Business (134,000 in 2008).

Two papers in this Special Issue contribute to this literature on cross-border M&As. Ellis et al. (2017) show that acquirers benefit from good country governance, such that the acquirer’s stock price reaction to acquisitions increases with the country level governance distance between the acquirer and the target. Renneboog et al. (2017) examine the impact of M&As on bondholders. Bondholder returns are larger in countries with stronger creditor rights and more efficient claims enforcement. These papers are important, as they show that the country-level distance between the acquirer and target affects the magnitude of transfer of governance, and this benefit is shared by shareholders and bondholders alike.

Table 2 highlights key papers in the literature on foreign ownership, foreign political connections, and foreign directors. Figure 2 shows that these topics have been substantially increasing in popularity over time, in contrast to work on directors more generally for example, which has been in relative decline in recent years. Foreign investors focus on different types of stocks, as shown in early work by Kang & Stulz (1997). Foreign investors do not destabilize markets (Choe, Kho, & Stulz, 1999). Foreign investment reduces the cost of capital (Stulz, 1999), and financial integration across countries lowers transactions costs and greater economic welfare (Martin & Rey, 2000), even though foreign money managers have transaction costs disadvantages (Choe, Kho, & Stulz, 2005). Foreign investors increase the expected value of private firms backed by venture capitalists (Cumming, Knill, & Syvrud, 2016), The positive effect of foreign ownership on firm value has been attributed to larger shareholders and higher long term commitment and involvement of such shareholders (Douma, George, & Kabir, 2006); however, in some cases international ownership is associated with deficient environmental standards (Dean, Lovely, & Wang, 2009).

Google Scholar hits on foreign directors, foreign shareholders, and related topics. This figure displays the number of Google Scholar hits as a percentage of the hits in 2008 for different search terms: Directors (84,300 hits in 2008), Foreign Directors (84 in 2008), Shareholders (32,400 in 2008), Foreign Shareholders (438 in 2008), Political Connections (2370 in 2008), and Sovereign Wealth Funds (1510 in 2008).

Cross-listing enables foreign ownership, and firms to bond to higher governance standards abroad to take advantage of more stringent securities laws in a host country’s capital markets (Coffee, 2002; Doidge, Karolyi, & Stulz, 2004; Doidge et al., 2007; Karolyi, 2012; Pagano, Roell, & Zechner, 2002). But the bonding explanation is incomplete as not all firms desire to cross-list (Coffee, 2002), and there is still a large effect of local national governance on firm value amongst firms that do cross-list (Cumming, Hou, & Wu, 2017). International adoption of other jurisdictions’ monitoring technology (Cumming & Johan, 2008) and regulations (Cumming, Johan, & Li, 2011) can enable the international transfer of governance and superior stock market outcomes such as new listings and liquidity. Regulators adopt from other jurisdictions monitoring technology (Cumming & Johan, 2008) and regulations (Cumming et al., 2011) that enable superior governance and stock market outcomes.

The mobility of governance is also facilitated by the increasing internationalization of the investor base. Specifically, global investors include sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), such as United Arab Emirates’s Abu-Dubai Investment Authority. SWFs may enforce governance standards in their portfolio firms that are different to the general governance practices in a specific location (Knill, Lee, & Mauck, 2012). Moreover, SWFs have a differential preference for private firms without a stock exchange listing, particularly in countries with lower legal standards (Johan, Knill, & Mauck, 2013), where the lack of transparency is suggestive of greater agency problems. Once companies become publicly listed, there is substantially more information released to the market, depending on the legal and cultural factors in a particular country (Boulton, Smart, & Zutter, 2017).

Another mechanism that can transfer governance includes CEO migration. MNCs can export monitoring technology and similar practices across national borders, and CEOs that have experience in foreign countries with stronger institutional environments may transfer knowledge about good governance (Cumming, Duan, Hou, & Rees, 2015). Generally, internal control systems and processes can be learned, therefore they are transferable/exportable, particularly in the context of emerging markets (Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, 2000; John & Senbet, 1998).

Further, foreign directors represent another channel of governance mobility as they may bring good governance standards from their home countries to the focal firm, especially if it is located in a country with low governance standards (Giannetti et al., 2015). Foreign directors have been shown to positively impact firm performance (Choi, Park, & Yoo, 2007), particularly when foreign directors have higher levels of foreign degrees and political connections (Rhee & Lee, 2008). There is some contrasting evidence, however, that while foreign directors make better M&A decisions, they are less often engaged in firm activities thereby worsening performance and requiring more earnings restatements, among other problems (Masulis et al., 2012).

Four important papers in this Special Issue contribute to the literature on foreign investors, foreign directors, and political connections. Aguilera et al. (2017) show that, in the presence of foreign investors, managers tend to be more optimistic in their early earnings forecasts, but have more long-term and timely adjustments relatively and avoid making last minute decisions. Calluzzo et al. (2017) show that sovereign wealth funds are attracted to firms that are more engaged in campaign finance, and hence can have a political influence in the target firm’s country. Sojli & Tham (2017) show that foreign political connections create large increases in firm value, improve access to foreign markets, and improve access to government contracts. Foreign board members coming from countries with more advanced institutions may export good governance to a local firm operating in a relatively less advanced institutional environment, and this improvement may be stronger when institutional differences between “exporting” and “importing” countries are high (Miletkov et al., 2017). These papers show that the identity of foreign owners is significant and may have interplay with foreign directors and political connections, and can substantially influence the governance and performance of firms in different institutional environments. All of these papers show that governance is mobile and a key competitive advantage.

Last but certainly not least, it is important to note that bad governance is also internationally mobile. Allred, Findley, Nielsen, & Sharman (2017) show that many firms flaunt international standards by setting up internationally shell corporations. Even among OECD countries, there are substantial numbers of shell companies that are not compliant with international standards. Tax haven based firms, by contrast, are more compliant with international standards. The popularity of research on shell companies is growing significantly (Fig. 1). Future research could continue to seek a better understanding of the causes and consequences of these shell companies.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our review of the literature suggests that mobility of corporate governance is very context specific in respect of the country level institutional conditions as well as the mode of international governance transfer. Insights into the causes and consequences of firm-specific international governance transfer can be gleaned from interdisciplinary analyses involving law, finance, management and related fields. There is a massive scope for further work on topic that makes use of these interdisciplinary perspectives that we have highlighted here.

In this introduction, we specifically emphasized four main ways in which governance is internationally mobile: international M&As, foreign investors, foreign directors, and foreign political connections. These related topics are the focus of the important papers in this Special Issue. As a limitation we note that these four channels are not the only ways in which governance practices may be transferred across countries. For example, prior studies identify other channels of the transfer of corporate governance, such as the proliferation of governance codes around the globe and the harmonization of accounting standards, which have been discussed in the related literature. Future IB studies should develop a more holistic picture of the mobility of corporate governance by looking at these diverse channels.

Examining multi-stakeholder perspective may reveal new important dimensions of the mobility of corporate governance, bearing in mind that the traditional view of corporate governance is heavily anchored on mechanisms for solving agency problems arising from conflicting interests between top management and outside shareholders. Debates about US-based board governance, including its optimal size, composition, and independence, are largely influenced by this convention. However, agency conflicts arising from other stakeholders have implications for the design of corporate governance intended to solve managerial agency problems. For instance, in an environment where we also have debt agency problems (Djankov et al., 2008), an optimally designed corporate board should represent a balance between the interests of outside shareholders and outside debtholders. Debtholder representation on the board is observed frequently outside the U.S. and U.K. corporate sectors, and future research may explore how some elements of the multi-stakeholder governance model can be transmitted from one country to another within the context of MNE global operations.

The papers in this Special Issue highlight important managerial and policy implications associated with the mobility of governance. International acquisitions benefit both acquirer and target firms, and particularly those firms with a greater institutional distance between them (Ellis et al., 2017; Renneboog et al., 2017). Foreign investors affect managerial behavior (Aguilera et al., 2017), and can have a political influence (Calluzzo et al., 2017). Foreign political connections positively affect firm value (Sojli & Tham, 2017). Foreign directors can positively affect firm value, particularly in countries with weak legal standards (Miletkov et al., 2017). The only negative aspect of mobility of governance is seen with the establishment of shell companies that are common and not compliant with international standards (Allred et al., 2017). Policymakers should work to encourage mobility of governance. At the same time, regulators could further cooperate to enforce international standards to prevent improper governance standards from being transferred across countries. Given recent events such as the Global Financial Crisis and all of its implications, this balance in policy could prove particularly challenging.

The impact of financial regulation on governance is particularly important in the contest of financial firms. To the extent that countries and regions vary in terms of regulatory schemes, the governance structure varies accordingly. Again, this is one example where the interaction between multiple agents and stakeholders matters in the design and mobility of governance. In fact, the design of bank management compensation and its incentive features play a vital role in the design of optimal banking regulation (John, Saunders, Senbet, 2000). Traditional banking regulation focuses on a two-party game with conflicting interests between the bank and the regulator. However, bank management is the key decision maker, and the bank risk incentives depend on the incentive structure of bank management compensation. John et al. (2000) show that, if these incentive features (e.g., bonus, salary, equity participation) are an input to the pricing of deposit insurance, an optimal banking regulation can be designed. Thus, the transmission mechanisms for governance mobility are broader when financial firms are considered. They arise from cross-border regulation and regulatory coordination.

In addition, development partners, as well as international financial institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank, can be transmission sources of governance for developing economies. This arises partly through technical assistance in financial sector development programs, but extends into non-financial firms as well. The quality of corporate governance is among the design features in the reform of financial systems in developing countries. This suggests an interesting research question into the relationship between governance and financial development with a focus on low income countries.

To conclude, this Special Issue poses important questions for corporate governance researchers in all of the respective fields, including IB, finance, economics, accounting and law. With the growing scale and scope of internationalization of business activities, the challenges facing executives in the global arena are considerably more demanding than those encountered in a domestic environment. The global context increases the diversity of stakeholders whose interests must be considered as well as the complexity of the governance problems facing MNCs and their leaders. Furthermore, companies competing in the global marketplace face a fundamental dilemma – how to balance the need for global consistency in corporate governance practices with the need to be sensitive to the demands and expectations of local stakeholders (Filatotchev & Stahl, 2015). Finding the appropriate balance between these competing demands is not always easy, and papers in this Special Issue help to map out future research directions in this increasingly important field.

References

Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. 2007. A theory of friendly boards. Journal of Finance, 62, 217–250.

Aggarwal, R., Klapper, L., & Wysocki, P. 2005. Portfolio preferences of foreign institutional investors. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29, 2919–2946.

Aguilera, R. V., Desender, K. A., López-Puertas, M., & Lee, J. H. 2017. The governance impact of a changing investor landscape: Foreign investors and managerial earnings forecasts. Journal of International Business Studies, this issue.

Aguilera, R. V., & Jackson, G. 2003. The cross-national diversity of corporate governance: Dimensions and determinants. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 447–465.

Allred, B., Findley, M. G., Nielsen, D. L., & Sharman, J. C. 2017. Anonymous shell companies: A global audit study and field experiment in 176 countries. Journal of International Business Studies, forthcoming.

Amin, A., & Cohendet, P. 2000. Organizational learning and governance through embedded practices. Journal of Management and Governance, 4(1), 93–116.

Anderson, R. C., Mansi, S. A., & Reeb, D. M. 2004. Board characteristics, accounting report integrity, and the cost of debt. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 37, 315–342.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. 2004. Board composition: Balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 209–237.

Bae, K.-H., & Goyal, V. K. 2009. Creditor rights, enforcement and bank loans. Journal of Finance, 84, 823–860.

Bebchuk, L. A., Cohen, A., & Ferrell, A. 2009. What matters in corporate governance? Review of Financial Studies, 22(2), 783–827.

Bebchuk, L. A., Cohen, A., & Wang, C. Y. 2013. Learning and the disappearing association between governance and returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(2), 323–348.

Bell, G., Filatotchev, I., & Aguilera, R. 2014. Corporate governance and investors’ perceptions of foreign IPO value: An institutional perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 57(1), 301–320.

Boulton, T., Smart, S., & Zutter, C. 2017. Conservatism and international IPO underpricing. Journal of International Business Studies, forthcoming.

Bris, A., & Cabolis, C. 2008. The value of investor protection: Firm evidence from cross-border mergers. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 605–648.

Brouthers, K. D. 2002. Institutional, cultural and transaction cost influences on entry mode choice and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 203–221.

Bruton, G., Filatotchev, I., Chahine, S., & Wright, M. 2010. Governance, ownership structure and performance of IPO firms: The impact of different types of private equity investors and institutional environments. Strategic Management Journal, 31(5), 491–509.

Bushman, R., Piotroski, J., & Smith, A. 2004. What determines corporate transparency? Journal of Accounting Research, 42, 207–252.

Bushman, R., & Smith, A. 2001. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 237–333.

Calluzzo, P., Dong, G. N., & Godsell, D. 2017. Sovereign wealth fund investments and the US political process. Journal of International Business Studies, forthcoming.

Cao, J., Cumming, D. J., Goh, J., Qian, M., & Wang, X. 2014. The impact of investor protection law on takeovers: The case of leveraged buyouts. Working Paper, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1100059.

Cao, J., Cumming, D. J., Qian, M., & Wang, X. 2015. Cross border LBOs. Journal of Banking & Finance, 50(1), 69–80.

Choe, H., Kho, B. C., & Stulz, R. M. 1999. Do foreign investors destabilize stock markets? The Korean experience in 1997. Journal of Financial Economics, 54(2), 227–264.

Choe, H., Kho, B. C., & Stulz, R. M. 2005. Do domestic investors have an edge? The trading experience of foreign investors in Korea. Review of Financial Studies, 18(3), 795–829.

Choi, J. J., Park, S. W., & Yoo, S. S. 2007. The value of outside directors: Evidence from corporate governance reform in Korea. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 42(4), 941–962.

Coase, R. H. 1960. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 56(4), 1–44.

Coates, J. C., & Srinivasan, S. 2014. SOX after ten years: A multidisciplinary review. Accounting Horizons, 28(3), 627–671.

Coffee, J. C., Jr. 2002. Racing towards the top? The impact of cross-listings and stock market competition on international corporate governance. Columbia Law Review, 102(7), 1757–1831.

Cremers, K., & Nair, V. 2005. Governance mechanisms and equity prices. Journal of Finance, 60, 2859–2894.

Cumming, D. J., Duan, T., Hou, W., & Rees, B. 2015. Do returnee CEOs transfer institutions? Evidence from newly public Chinese entrepreneurial firms. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2780680.

Cumming, D. J., Hou, W., & Wu, E. 2017. The value of home country governance for cross-listed stocks. European Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Cumming, D. J., & Johan, S. 2008. Global market surveillance. American Law and Economics Review, 10, 454–506.

Cumming, D. J., Johan, S. A., & Li, D. 2011. Exchange trading rules and stock market liquidity. Journal of Financial Economics, 99(3), 651–671.

Cumming, D. J., Knill, A., & Richardson, N. 2015b. Firm size, institutional quality and the impact of securities regulation. Journal of Comparative Economics, 43(2), 417–442.

Cumming, D. J., Knill, A., & Syvrud, K. 2016. Do international investors enhance private firm value? Evidence from venture capital. Journal of International Business Studies, 47, 347–373.

Cumming, D. J., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., McCahery, J., & Schwienbacher, A. 2015. Tranching in the syndicated loan market around the world, Working Paper, York University.

Cumming, D. J., & Walz, U. 2010. Private equity returns and disclosure around the world. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4), 727–754.

Daines, R. 2001. Does Delaware law improve firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 62, 525–558.

David, P. A. 1994. Why are institutions the carriers of history? Path dependence and the evolution conventions, organizations, and institutions. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 5(2), 205–220.

Dean, J. M., Lovely, M. E., & Wang, H. 2009. Are foreign investors attracted to weak environmental regulations? Evaluating the evidence from China. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 1–13.

Djankov, S., Hart, O., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. 2008. Debt enforcement around the world. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 1105–1149.

Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. 2007. Private credit in 129 countries. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 299–329.

Doidge, C., Karolyi, G. A., & Stulz, R. M. 2004. Why are foreign firms listed in the US worth more? Journal of Financial Economics, 71(2), 205–238.

Doidge, C., Karolyi, G. A., & Stulz, R. M. 2007. Why do countries matter so much for corporate governance? Journal of Financial Economics, 86, 1–39.

Douma, S., George, R., & Kabir, R. 2006. Foreign and domestic ownership, business groups, and firm performance: Evidence from a large emerging market. Strategic Management Journal, 27(7), 637–657.

Dyck, A., Morse, A., & Zingales, L. 2010. Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? Journal of Finance, 65(6), 2213–2253.

Dyck, A., & Zingales, L. 2004. Private benefits of control: An international comparison. Journal of Finance, 59, 537–600.

Ellis, J. A., Moeller, S. B., Schlingemann, F. P., & Stulz, R. M. 2017. Portable country governance and cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, this issue.

Esty, B. C., & Megginson, W. L. 2003. Creditor rights, enforcement, and debt ownership structure: Evidence from the global syndicated loan market. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38, 37–60.

Filatotchev, I., & Nakajima, C. 2014. Corporate governance, responsible managerial behavior, and CSR: Organizational efficiency versus organizational legitimacy? Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 289–306.

Filatotchev, I., & Stahl, G. 2015. Towards transnational CSR: Corporate social responsibility approaches and governance solutions for multinational corporations. Organizational Dynamics, 44, 121–129.

Filatotchev, I., & Wright, M. 2011. Agency perspective on corporate governance of multinational enterprises. Journal of Management Studies, 48(2), 471–486.

Giannetti, M., Liao, G., & Yu, X. 2015. The brain gain of corporate boards: Evidence from China. Journal of Finance, 70(4), 1629–1682.

Giroud, X., & Mueller, H. M. 2011. Corporate governance, product market competition, and equity prices. Journal of Finance, 66(2), 563–600.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. 2003. Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 107–155.

Haselmann, R., Pistor, K., & Vig, V. 2010. How law affects lending. Review of Financial Studies, 23(2), 549–580.

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. 2000. Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249–267.

Huson, M., Parrino, R., & Starks, L. 2001. Internal monitoring mechanisms and CEO turnover: A long-term perspective. Journal of Finance, 56(6), 2265–2297.

Jackson, H., & Roe, M. 2009. Public and private enforcement of securities laws: Resource-based evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 93, 207–238.

Johan, S. A., Knill, A., & Mauck, N. 2013. Determinants of sovereign wealth fund investment in private equity vs public equity. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(2), 155–172.

John, K., & Senbet, L. W. 1998. Corporate governance and board effectiveness. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(4), 371–403.

John, K., Saunders, A., & Senbet, L. W. 2000. A theory of bank regulation and management compensation. Review of Financial Studies, 13(1), 95–125.

Johnson, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2000. Tunneling. American Economic Review, 90(2), 22–27.

Judge, W. Q., Douglas, T. J., & Kutan, A. M. 2008. Institutional antecedents of corporate governance legitimacy. Journal of Management, 34(4), 765–785.

Kang, J.-K., & Stulz, R. M. 1997. Why is there a home bias? An analysis of foreign portfolio ownership. Journal of Financial Economics, 46(1), 3–28.

Karolyi, G. A. 2012. Corporate governance, agency problems and international cross-listings: A defense of the bonding hypothesis. Emerging Markets Review, 13(4), 516–547.

Klapper, L. F., & Love, I. 2004. Corporate governance, investor protection, and performance in emerging markets. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10(5), 703–728.

Knill, A., Lee, B. S., & Mauck, N. 2012. Bilateral political relations and the impact of sovereign wealth fund investment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(1), 108–123.

Kor, Y. Y. 2003. Experience-based top management team competence and sustained growth. Organization Science, 14(6), 707–719.

Krause, R., Filatotchev, I., & Bruton, G. 2016. When in Rome look like Cesar? Investigating the link between demand-side cultural power distance and CEO power. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1361–1384.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Pop-Eleches, C., & Shleifer, A. 2004. Judicial checks and balances. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 445–470.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2006. What works in securities laws. Journal of Finance, 61(1), 1–31.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1997. Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131–1150.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1115–1155.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 2000. Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1–2), 3–27.

Leuz, C., Nanda, D., & Wysocki, P. D. 2003. Earnings management and investor protection: An international comparison. Journal of Financial Economics, 69(3), 505–527.

Leuz, C., & Wysocki, P. D. 2016. The economics of disclosure and financial reporting regulation: Evidence and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Research, 54, 525–622.

Li, D., Moshirian, F., Pham, P. K., & Zein, J. 2006. When financial institutions are large shareholders: The role of macro corporate governance environments. Journal of Finance, 61(6), 2975–3007.

Lipton, M., & Lorsch, J. W. 1992. A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. The Business Lawyer, 48, 59–77.

Mahoney, J. T., & Kor, Y. Y. 2015. Advancing the human capital perspective on value creation by joining capabilities and governance approaches. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29, 295–308.

Martin, P., & Rey, H. 2000. Financial integration and asset returns. European Economic Review, 44(7), 1327–1350.

Martynova, M., & Renneboog, L. 2008. Spillover of corporate governance standards in cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(3), 220–223.

Masulis, R., Wang, C., & Xie, F. 2012. Globalizing the boardroom—the effects of foreign directors on corporate governance and firm performance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(3), 527–554.

McCahery, J., Sautner, Z., & Starks, L. 2017. Behind the scenes: the corporate governance preferences of institutional investors. Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Miletkov, M. K., Poulsen, A. B., & Wintoki, M. B. 2017. Foreign independent directors and the quality of legal institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, this issue.

Moore, C., Bell, G., Filatotchev, I., & Rasheed, A. 2012. Foreign IPO capital market choice: Understanding the institutional fit of corporate governance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(8), 914–937.

Nini, G., Smith, D., & Sufi, A. 2012. Creditor control rights, corporate governance and firm value. Review of Financial Studies, 25(6), 1713–1761.

O’Hare, S. 2003. Splitting the board by stealth, Financial Times, January 14.

Pagano, M., Roell, A., & Zechner, J. 2002. The geography of equity listing: Why do companies list abroad? Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2651–2694.

Palepu, K. G. 1986. Predicting takeover targets. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 8, 3–35.

Qi, Y., Roth, L., & Wald, J. 2017. Creditor protection laws, debt financing, and corporate investment over the business cycle, Journal of International Business Studies, forthcoming.

Renneboog, L., Szilagyi, P. G., & Vansteenkiste, C. 2017. Creditor rights, claims enforcement, and bond performance in mergers and acquisitions, Journal of International Business Studies, this issue.

Rhee, M., & Lee, J.-H. 2008. The signals outside directors send to foreign investors: Evidence from Korea. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(1), 41–51.

Romano, R. 2005. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the making of quack corporate governance. The Yale Law Journal, 114(7), 1521–1611.

Rose, C. 2005. The composition of semi-two-tier corporate boards and firm performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13, 691–701.

Ruigrok, W., Peck, S., & Tacheva, S. 2007. Nationality and gender diversity on Swiss corporate boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14(4), 546–557.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1997. A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783.

Short, H., & Keasey, K. 1999. Managerial ownership and the performance of firms: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5, 79–101.

Skinner, D. 1994. Why firms voluntarily disclose bad news. Journal of Accounting Research, 32, 38–60.

Smith, C. W., & Warner, J. B. 1979. On financial contracting: An analysis of bond covenants. Journal of Financial Economics, 7, 117–161.

Sojli, E., & Tham, W. W. 2017. Foreign political connections, Journal of International Business Studies, this issue.

Spamann, H. 2010. The “Antidirector Rights Index” revisited. Review of Financial Studies, 23(2), 467–486.

Stulz, R. 1999. Globalization, corporate finance, and the cost of capital. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 12(3), 8–25.

Subramanian, G. 2004. The disappearing Delaware effect. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 20(1), 32–59.

Suchman, M. C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Syvrud, K., Knill, A., Jens, C., & Colak, G. 2012. Are all international IPOs created equally? Florida State University and Tulane University Working Paper.

Tihanyi, L., Griffith, D. A., & Russell, C. J. 2005. The effect of cultural distance on entry mode choice, international diversification, and MNE performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 36, 270–283.

Wang, X. 2010. Increased disclosure requirements and corporate governance decisions: Evidence from chief financial officers in the pre- and post-Sarbanes–Oxley periods. Journal of Accounting Research, 48, 885–920.

Wymeersch, E. 1998. A status report on corporate governance rules and practices in some continental European states. In K. J. Hopt, H. Kanda, M. J. Roe, E. Wymeersch, & S. Prigge (Eds.), Comparative Corporate Governance. The State of the Art and Emerging Research (pp. 659–682). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by John Cantwell, Editor-in-Chief, 12 December 2016. This article was single-blind reviewed.

Accepted by John Cantwell, Editor-in-Chief, 12 December 2016. This article was single-blind reviewed.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cumming, D., Filatotchev, I., Knill, A. et al. Law, finance, and the international mobility of corporate governance. J Int Bus Stud 48, 123–147 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0063-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0063-7