Abstract

Charities engage customers with their cause to encourage charity support behaviours (CSB) and often use storytelling to create that impact. We argue that mechanisms underpinning this process manifest in the story recipients’ engagement with a sequence of focal objects—from the story (i.e. through narrative transportation) to the cause it concerns (i.e. customer engagement), to the charity that supports the cause (i.e. CSB). An online survey (n = 585) required participants to alternatively read a story of a person experiencing homelessness or a general text about homelessness. Results show that narrative transportation leads to CSB through different cognitive, affective, and conative customer engagement paths. Using both narrative and non-narrative text, managers can appeal to specific dimensions of customer engagement to elicit high and low involvement CSB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Competition in the non-for-profit sector (Hou, Eason, and Zhang 2014) sees many charities using stories to distinguish themselves from others (Mitchell and Clark 2021), as a strategy to elicit support behaviours from the public (Wymer and Akbar 2019). Organisations and brands use stories to create and convey meaning (Bublitz et al. 2016; Key et al. 2021), enhance brand perceived value (Ganassali and Matysiewicz 2021) and foster relations with customers (Sanders and Krieken 2018), as they, in turn, create meaning through awareness of thoughts, feelings, behaviours in the rhythm of the unfolding story (Smith and Liehr 2014).

While storytelling as a tool for marketing communication, engagement, and behaviour change has established itself in other domains, its use in speaking for others (Fenton 2021) and engaging people in charitable behaviour (Song 2021) poses additional challenges. In the context of charity support behaviours (CSB) (Peloza and Hassay 2007), the benefits are not distributed to the story recipient and potential helper, making the link between engagement with the story and behavioural outcomes more challenging. Apart from benefits being shared, delayed or given up (Lay and Hoppmann 2015), there are two additional challenges for prosocial storytelling. In contrast to commercial stories that appeal to positive emotions and therefore lower resistance (van Laer et al. 2019), narratives raising awareness of broader societal problems are more likely to evoke negative emotions that can reduce willingness to help; they are also less clear about the expected behaviours (Moore et al. 2021). Similar lack of clarity about the value of prosocial action can create barriers in social interactions. Both giver and receiver calculate the value of their behaviour but take different approaches: givers would expect to be reciprocated based on the cost of their behaviour, whereas receivers would primarily (or exclusively) reciprocate on the basis of the benefit they received—such perceived imbalance and inefficiencies pose another challenge for prosocial context (Zhang and Epley 2009). Nevertheless, narratives—through facilitating empathetic and emotional responses (Walkington et al. 2020; Herrera et al. 2018), can lead to more beneficial behavioural intentions towards marginalised and stigmatised groups (Olivier 2012). This paper addresses this complex scenario and explores the links between engagement with a story, the cause it concerns, and ultimately with the charity supporting this cause.

Storytelling literature conceptualises the use of storytelling to encourage customer engagement (Dessart and Pitardi 2019) or charity support behaviours (Bublitz et al. 2016); however, there are no studies that comprehensively consider the interplay between the different forms of engagement in this context. Empirical studies in a prosocial context consider narrative transportation (Bal and Veltkamp 2013; Morris et al. 2019; Rathje et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2019), or customer engagement (Robiady et al. 2021) in isolation, or omit these engagement concepts as mechanisms between storytelling and charity support (Correa et al. 2015; Nguyen 2015; Shreedhar 2021). Although some studies take a more comprehensive view on a variety of charity support behaviours (Hou et al. 2014; Matos and Fernandes 2021; Wymer and Akbar 2019), storytelling is not considered as a tool to evoke them. Our research is a response to the fragmentation and discordance of empirical studies on potential mechanisms of storytelling’s influence on charity support behaviours. The extended study of antecedents and consequences of narrative transportation (van Laer et al. 2014), the model of individual charity giving behaviours (Sargeant 2014), analyses of multidimensional volunteering engagement (Conduit et al. 2019), and charity support activities mapped against the dimensions of perceived benefits (Faulkner and Romaniuk 2019) each constitute promising foundations for more comprehensive studies of the role of engagement in charity support behaviours. This paper addresses this challenge and seeks to understand how the considered focal object of engagement and the dimensionality of engagement inform charity support.

Sparse empirical research into the use of storytelling in eliciting a spectrum of charity support behaviours, and the lack of a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms underlying this impact underpins the need for this study. We propose that the path of charity supporters’ engagement leads from narrative transportation (i.e. engagement with a story about a person experiencing homelessness), through customer engagement with a cause (i.e. engagement with the cause of homelessness), to charity support behaviours (i.e. behavioural engagement with the charity—in this instance, an organisation supporting people experiencing homelessness). Engaging with a sequence of different focal objects has yet to be considered in the engagement literature and is the essence of the mechanisms described in this paper and, as such, contributes to theory, literature, and practice.

As storytelling is a tool for preserving and transmitting information (Weedon 2018), narratives not only help people understand issues and explore reality but also draw them into another world (van Laer et al. 2019); transported people express story-consistent attitudes (Green 2014). The theoretical assumptions of the project are based on two pillars: narrative transportation theory (Green 2008) and customer engagement theory (Brodie et al. 2011). The theory of narrative transportation posits that when consumers lose themselves in a story, their attitudes and intentions change to reflect that story (Green 2008), hence the interest to marketers, especially in the charity support context. The theoretical foundations of customer engagement emphasise that the context determines not only the intensity and complexity of customer engagement, but also its specific antecedents and consequences (Brodie et al. 2011). The consistent contextual setting of the focal objects (the story, the cause, the charity related to homelessness) aims to investigate the mechanisms of engagement underlying the impact of storytelling on charity support behaviours through customer engagement with the cause. We posit that transported story recipients engage cognitively, affectively, and behaviourally with the cause the story is about, and finally direct their engagement to the charity supporting the cause (Bowden et al. 2017). We also recognise that the desired charity support behaviours (CSB) may be purely cause-driven (high involvement CSB), but can also stem from other, value-driven motivations (low involvement CSB)—paths leading through narrative transportation and customer engagement to both outcomes will be reflected in this paper.

Our research contributes by exploring the mechanisms of engagement to understand how storytelling impacts charity support behaviour (CSB). It explicates consumer engagement with both the story and the cause as mechanisms that facilitate the relationship between storytelling and charity support behaviours; hence contributing to narrative transportation and customer brand engagement literature. We contribute to the literature on customer brand engagement by providing a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the interplay among engagement with three focal, interconnected objects (i.e. the story, the cause, and the charity organisation). This addresses a recent call from Hollebeek et al. (2023) for further studies of additional engagement objects (beyond the brand and social media content) and the interplay among these objects. While the relationship between storytelling and charity support has been previously examined, the research has been fragmented and produced mixed results. By considering customer engagement as a multidimensional construct, we contribute to the literature by demonstrating the different effects of cognitive, affective, and conative dimensions, and expand our understanding of negatively valenced engagement by exploring positive effects of negative affective responses to a story. We investigate both high and low involvement CSB to explore customers’ cause and value-driven motives when supporting a charity. Therefore, we bring implications for researchers and practitioners of customer engagement in a challenging prosocial context.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Storytelling in a prosocial context

Storytelling, a process of composing narratives, translating the concept (a story) into the material product of telling the story (a narrative) through medium (Sibierska 2017), serves to move a recipient away from the here and now (Gerrig 1993) and forms a basis of the narrative transportation effect. The best stories are the ones people get lost in (Weedon 2018), but the narrator is not the only architect of that experience; therefore, storytelling opens the way for the recipient to change attitudes and beliefs, and exhibit post narrative behaviours.

A review of the literature on storytelling in various contexts/fields, as well as studies on charity support behaviours not considering storytelling (see Appendix B), identified three main issues: fragmentary considerations of narrative transportation and customer engagement as mechanisms of storytelling’s multi-context and prosocial outcomes, an unsystematic approach to charity support behaviours as consequences of storytelling, and finally, ambiguity and challenges of additional mechanisms considered in the storytelling literature.

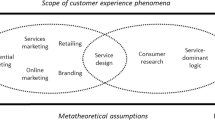

While researchers have attempted to build conceptual frameworks explaining the impact of storytelling on customer engagement (Dessart and Pitardi 2019) or its use in encouraging charity support behaviours (Bublitz et al. 2016), the empirical research to date is piecemeal and addresses narrative transportation (Bal and Veltkamp 2013; Green 2004; Morgan et al. 2009; Morris et al. 2019; Rathje et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2019), or customer engagement (Robiady et al. 2021) independently, or omit these mechanisms from conceptual models (Correa et al. 2015; Merchant et al. 2010; Nguyen 2015; Shreedhar 2021). Both constructs are addressed only outside the context of prosocial behaviour (Coker et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2016), which opens a gap we want to address in this research.

Moreover, storytelling researchers take a fragmented approach to charity support behaviours, analysing mainly donations (Barraza et al. 2015; Nguyen 2015; Rathje et al. 2021), general helping behaviours (Kossowska et al. 2020), or supporting the cause (Herrera et al. 2018). Going beyond donations (Choi et al. 2020; Maleki and Hosseini 2020) or volunteering (Hansen and Slagsvold 2020; Harp et al. 2017) and taking a more complex approach to CSB is rare (Bennett 2013; Matos and Fernandes 2021; Wymer and Akbar 2019), and does not consider storytelling as a trigger. These gaps highlight the need for a more comprehensive analysis of a range of charity support behaviours evoked by stories.

In contexts other than prosocial, narrative transportation is recognised as a means to influence attitudes (Boukes and LaMarre 2021), learning outcomes (Moore and Miller 2020) or health (Cole 2010), and some researchers suggest customer engagement as one of the mechanisms of storytelling’s impact (Coker et al. 2021; Kemp et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2016). Although some researchers recognise cognitive, affective, and conative effects as mechanisms of storytelling’s impact (Ben Youssef et al. 2019; Dessart and Pitardi 2019), the findings are mixed and only applicable in certain contexts (i.e. include boundary conditions). Examples of these determinants include: the strength of facts presented in a story (Krause and Rucker 2020), an organisation’s capability of telling a story (Mitchell and Clark 2021), perceived behavioural control (Pressgrove and Bowman 2020), growth mindset (Carnevale et al. 2018), or story character and content (Shreedhar 2021). Researchers also suggest that customer engagement does not have to mediate the impact of storytelling technique on donations (Robiady et al. 2021), warn against inauthentic storylines that can evoke affective resistance (Appel 2022) and highlight the need for additional actions (going beyond storytelling) to mitigate a detrimental impact of negative emotions (Merchant et al. 2010). Addressing such uncertainties lies at the heart of this research.

Recognising the relatively wealthy research on storytelling and charity support behaviours (see Appendix B), yet addressing its ambiguities, challenges, and fragmentation from the empirical point of view, we propose that the impact of storytelling on charity support behaviours can be based on the mechanisms of engagement with various focal objects (Brodie et al. 2011): a story, a cause, and a charity.

Narrative transportation—engagement with a story

Narrative transportation (NT), engagement with a story, is the extent to which a story receiver empathises with the story characters, and the story plot activates their imagination and leads them to experience suspended reality during story reception (van Laer et al. 2014). It is argued that narrative transportation effect is stronger when the story falls into commercial (versus non-commercial) domain (van Laer et al. 2019), and research to date has identified several significant antecedents of this process. Some of them are under the control of the storyteller: identifiable story characters (Green 2004), an imaginable story plot, and verisimilitude (van Laer et al. 2014), while others, such as familiarity (Mulcahy and Gouldthorp 2016), attention (Polichak and Gerrig 2002), education (Green 2014), and gender (Green and Brock 2000) are related to the story receiver. According to narrative transportation theory (Green 2008), story recipients can disconnect from existing beliefs (Green 2004; Green and Brock 2000) and adopt story-consistent beliefs (Marsh and Fazio 2006), attitudes and intentions (van Laer et al. 2014) and are more willing to act (Dal Cin et al. 2007). In considering the distinction of cognitive, affective, and conative responses to a story (van Laer et al. 2014), and analysing the effects of narrative transportation, this research aims to understand narrative transportation as a vital variable in the process of changing human behaviour through storytelling, and a crucial phase of the audience’s engagement—with a story as a focal object.

Customer engagement—engagement with a cause

Although the concept of narrative engagement is considered in the literature as a substitute for narrative transportation (Samur et al. 2020), we utilise customer engagement as a distinct and different concept consistent with Brodie et al. (2011) and Hollebeek et al. (2019), as it is generally considered in marketing literature. Narrative transportation reflects the engagement that occurs between the reader as the focal subject and the story itself as the focal object. Whereas, customer engagement has been considered a broader construct representing motivational interactions going beyond story contexts (Dessart and Pitardi 2019), and a psychological state that occurs by interactive, co-creative customer experiences with a focal object in service relationships (Brodie et al. 2011). It is a multidimensional construct that considers the cognitive, affective, and conative (behavioural) investments in the interaction between the individual (focal subject) and the focus of the interaction, often the brand (Hollebeek and Chen 2014), a focal person of interest (Sim and Plewa 2017), or in this instance, the social issue of interest, i.e. homelessness. It is worth explaining that by a customer, we mean an active, voluntary contributor of resources (time, money, goods, knowledge, skills), a person actually and potentially interacting with a charity.

Although researchers consider negatively valenced brand engagement (Hollebeek and Chen 2014), the negative affective engagement that would lead to positive effects is not yet considered in academic literature. This is crucial in the context of cause-related marketing due to common sensitivity of the covered issues and emotional appeals used by charities. Negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours can lead to negative engagement with an organisation (Naumann et al. 2017), reduce customer brand engagement (Bowden et al. 2017) and induce negative word of mouth (Naumann et al. 2020). However, responding to a call for research on positive prosocial effects of negative emotions (Naimi et al. 2023), we explore the impact of negative affective engagement on charity support behaviours; this is one of the key contributions of this research. The question about the type of emotions and their role in the prosocial effects of engagement (Conduit et al. 2019) is justified; negative emotions often have a stronger impact on social implications than positive affective responses (Gross 2002), and moral guilt can initiate such social behaviour as volunteering or donations (McKay et al. 2013). Extending the dimension of affective engagement with negative responses allowed for a more in-depth analysis of engagement with the cause that the story concerned (i.e. homelessness).

The customer engagement literature has considered many outcomes, including word of mouth (Vivek et al. 2012), loyalty (Dessart et al. 2015), knowledge and skill development (Hollebeek et al. 2019), purchase or referral behaviour (Kumar and Pansari 2016). In terms of prosocial effects, hitherto research shows how engagement, linked to the availability of resources (Jones 2006), and prosocial values (Shantz et al. 2014), encourages volunteering, creates value to retain volunteers in organisations (Conduit et al. 2019), impacts charitable giving (Bennett 2013), or donations to corporate social responsibility programmes (Song 2021). With such a fragmented approach so far, this paper addresses the need for more comprehensive study of charity support behaviours (CSB).

Charity support behaviours—engagement with a charity

In commercial, entertainment or educational contexts, narratives emphasise benefits on the part of the story recipient, while engaging people in prosocial actions presupposes sharing, delaying in time or giving up emotional, financial, cognitive or psychological benefits (Lay and Hoppmann 2015). Prosocial responses to a story are reflected in low and high involvement charity support behaviours (CSB). Transportation to the world of the narrative is to modify the receivers’ perception of the real world (van Laer et al. 2019) and ultimately—through looking at the social problem from the perspective of the story’s character—engage with this problem and with an organisation through charity support behaviours—it is a complex system with multiple interactions.

Although sympathy and personal relevance of a cause are possible factors underlying the will to donate to particular types of charity (Bennett 2003), people can positively support charity despite not strongly identifying with the cause (Peloza and Hassay 2007). We adopt the typology of charity support behaviours (CSB) considering the degree of engagement with a charity organisation, and divide these behaviours into low and high involvement CSB (Peloza and Hassay 2007). The typology is based on a division between involved supporters, who are passionate about a specific charity or cause and driven by altruistic motivations to support the cause and thereby the charity, and uninvolved supporters with a more egoistic or utilitarian motivation, with little consideration for the charity or cause (Peloza and Hassay 2007). The latter group’s charity support behaviours are therefore not cause-driven, but value-driven and depend on a cost–benefit analysis (Bendapudi et al. 1996). High involvement CSB can take a form of donating time and energy to a charity organisation (volunteering, referrals), donating money and goods, purchasing goods with charity affiliations (CRM, charity products), or participation in charity events (cause-focused). Individuals who are less involved with the cause represented by the charity can still perform activities similar to the aforementioned behaviours. Community service, functional donations (with tax deduction in mind), gifts being a form of recycling/disposal, purchasing goods with charity affiliations (product-focused), event participation (event-focused) are also valued forms of charity support. Less involved forms of CSB can serve as a potential introduction to the charity and ultimately can lead to greater engagement and subsequent support (Peloza and Hassay 2007), as it is easier to increase engagement among people already supporting the charity than attract new ones (Hansen and Slagsvold 2020). Considering both types of CSB and the paths leading to them provides a more complete picture of the dependencies determining engagement with a charity organisation as another focal object of engagement after the story and the cause.

Hypotheses development

This project aims to explore the impact of storytelling on charity support behaviours and answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How does narrative transportation influence charity support behaviours?

RQ2: How does cognitive, affective, and conative engagement mediate the relationship between narrative transportation and charity support behaviours?

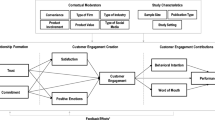

We investigate the audience’s engagement with the story (narrative transportation into the story of a homeless person) and the cause (engagement with homelessness as a social issue). When building the conceptual framework, we draw on principles of narrative transportation theory (Green et al. 2008) and customer engagement theory (Brodie et al. 2011) and consider customer engagement (cognitive, affective, and conative) as a mechanism leading to expected outcomes: engagement in charity support behaviours. Narrative transportation leads to charity support behaviours, and multidimensional engagement with the cause mediates this relationship. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model with hypotheses developed in the following discussion.

Narrative transportation and cognitive engagement

Narratives can exert a persuasive cognitive influence through several different mechanisms. First, transportation reduces counterarguing about the issues raised in the story or negative cognitive responding as the audience focuses on the plot unfolding (Nabi and Green 2015). While critical thoughts are reduced (Slater and Rouner 2002), story-consistent beliefs (Green 2014; Marsh and Fazio 2006) and narrative thoughts (van Laer et al. 2014) appear. Cognitive engagement remains (Chen and Chang 2017), even though instilling a bias in people’s information processing or reducing the degree of message elaboration (Krause and Rucker 2020) limits counterarguing against persuasive messages.

Second, narrative transportation can affect beliefs as it makes story events seem more like personal experience (Green 2004)—if readers or viewers feel like they have participated in narrative events, the lessons arising from these events seem stronger. Narrative transportation theory perceives an individual’s ability to process information through self-referencing, a cognitive process of comparing new messages with existing personal knowledge and beliefs (Rutledge 2015). Finally, identification with story characters can play a significant role in changing beliefs, and make their statements or experience of particular importance to the story receiver (Green 2008). Knowledge of a social problem, gained through insight through the story told, facilitates cognitive engagement with the cause; therefore, we propose:

H1a: Narrative transportation positively influences cognitive engagement.

Narrative transportation and affective engagement

Narrative transportation has a moderate positive correlation with empathy (Davis 1983), and emotional, empathic responses mediate the relationship between the tendency to become transported into narratives and attitudes (Mazzocco et al. 2010). Empathy, associated with a higher level of personal resonance, transportation, and mental story processing, can facilitate emotional contagion (van Laer et al. 2014). Emotions, vital in maintaining interest in narration (Nabi and Green 2015), are more often shared with others (Rimé 1995) and bring the audience back to the narrative, inspire search for new information and experiences, and help memorise the narrative message (Green and Brock 2002). Emotions are considered not as a feature of a narrative (Escalas, Moore, and Britton 2004), but as the audience’s affective responses, both positive and negative, evoked by a story and narrative transportation (Lamarre and Landreville 2009). The emotions evoked by the story fuel the affective engagement with the cause, and its nature can be both positive and negative. Hence, we posit:

H1b: Narrative transportation influences positive affective engagement.

H1c: Narrative transportation influences negative affective engagement.

Narrative transportation and conative engagement

Conation, as the aspect of mental process or behaviour directed towards action or change, connects cognition and affect to action (Militello et al. 2006), and the conative component of engagement, behavioural manifestations resulting from motivational drivers (van Doorn et al. 2010), seems crucial in the context of the actual narrative transportation effects on charity support behaviours. However, the intentions, motivations, the will to perform action, that is, the conative engagement with the cause resulting from storytelling and narrative transportation is not discussed. Research on intentions to share information (Kang et al. 2020) confirms the impact of narrative transportation on conative engagement, however, indicating that emotions strongly moderate this effect. Inviting people to a narrative allows them to engage more in behavioural interactions with the cause that the story concerns; for instance, searching for additional information or possible ways of support. As people are looking rather for experiences than things, the more experiences are created for the desired behaviours, the higher the chance of the change (Passon 2019). The goal of the immersive story is to lead the audience to the desired behavioural outcome (Bublitz et al. 2016) through engaging with the cause. Thus, we propose:

H1d: Narrative transportation positively influences conative engagement.

Narrative transportation and charity support behaviours

Although research on the impact of narrative transportation on overt behaviour is scarce, van Laer et al. (2014) propose that the more narrative transportation increases, the more story-consistent behaviour increases. As it is difficult to control current behaviour under the influence of far-reaching, distant aims, short-term, achievable goals help people succeed by controlling effort, resources, and activities. As such, a story that shows how to overcome potential barriers can increase self-efficacy and intention to act (Pressgrove and Bowman 2020). Stories often contain a key issue or moral to which recipients can return to control their behaviour in accordance with the values derived from the story. This increases the chances of a long-term or even deferred narrative transportation impact (van Laer et al. 2014), enhances the continuity of behaviour based on adapted patterns and helps formulate a virtuous cycle in which life and story build on, and sustain each other (Dunlop 2022). This is possibly crucial for initiating lasting prosocial behaviour, for example, in the form of charity support behaviours (CSB). Potential behavioural effects may be increased when two preconditions are met: (i) a person’s ability to perform a particular behaviour and (ii) a lack of constraints to inhibit the behaviour (Fishbein and Yzer 2003). The perceived ability to behave compares with any barriers to overcome, and the result of these considerations determines the action. Mental imagery, as one of the dimensions of narrative transportation, helps the story recipient imagine future behaviours, making actions easier and more probable to be taken (Gregory et al. 1982; Schlosser 2003). The direct path from engagement with a story to engagement with a charity, without deeper engagement with the cause (as their common denominator), might reflect impulsive, immediate behavioural responses facilitated by the instant opportunity to help (Merchant et al. 2010) or by high expectations of perceived effectiveness of support (Kossowska et al. 2020). As a result, we propose:

H2a: Narrative transportation positively influences high involvement CSB.

H2b: Narrative transportation positively influences low involvement CSB.

Cognitive engagement and charity support behaviours

Intentions are derived from normative and control beliefs, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control over behaviour (Ajzen 2011). Core determinants of people’s motivations and actions are knowledge, perceived self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, and the perceived facilitators and obstacles to the changes they want to implement (Bandura 2004). Human behaviours are both internally motivated and externally driven, contextual, and whether intentions predict actions depends sometimes on factors beyond the individual’s control. Nevertheless, cognitive assessment of the situation in terms of invested resources and potential benefits (personal, but also shared or offered to others) can be a strong determinant of action. For people with a lower or moderate level of empathy, it is a cognitive process of perspective-taking that contributes to a higher level of prosocial moral reasoning (Yagmurlu and Sen 2015). Engagement with an informative and rationally valuable story about a social issue supports the transition through the cognitive stage of the decision-making process. Positive evaluation of potential possibilities and control over socially desirable behaviour can strengthen the link between engagement with the cause and with the charity through support behaviours. Hence, we propose:

H3a(i): Cognitive engagement positively influences high involvement CSB.

H3a(ii): Cognitive engagement positively influences low involvement CSB.

Affective engagement and charity support behaviours

Affective engagement is often omitted when addressing socially significant problems with highly cognitive messages aimed at behavioural change (Burke et al. 2018). However, the affective component in the analysis of human behaviour appears in two ways: emotions serve as background factors influencing behavioural, normative and control beliefs or as catalysts for choosing already established and remembered norms (Ajzen 2011). Affective states systematically influence the strength, evaluation of beliefs, and their relevance in a given situation. A relationship between cognitive skills, intelligence and prosocial behaviour is derived from a better perception and understanding of the feelings and needs of others (Guo et al. 2019); this, in turn, contributes to more empathic reactions, and increase the willingness to help. Empathy (defined in both cognitive and affective dimensions) can evoke two different emotional responses: sympathy and personal distress (Yagmurlu and Sen 2015). Due to the controversial and sensitive narrative context (homelessness), we also included the negative aspect of the affective dimension of engagement. Moral emotions can have both positive and negative tones (for instance, anger, shame, guilt), and unfair story events related to a difficult social issue make recipients experience heightened activity in areas of the brain associated with negative emotional states. Such responses can lead to prosocial behaviours as corrective actions, both to stop morally inappropriate behaviour and to support the victim (Greenbaum et al. 2020). Negative emotional responses may be positively related to awareness and action (Borum Chattoo and Feldman 2017), and both the positive and negative affective reactions can predict behavioural changes beyond what the level of narrative transportation predicted (Murphy et al. 2011), reflecting the strong emotional engagement with the cause. The bidirectional nature of potential affective reactions reflects the proposed division into positive and negative affective engagement. It does not mean opposing influence on possible charity support behaviours but rather shows different potential routes and motivations. We consider both positive and negative affective engagement with the cause as a potential factor enhancing charity support behaviours (CSB):

H3b(i): Positive affective engagement influences high involvement CSB.

H3b(ii): Positive affective engagement influences low involvement CSB.

H3c(i): Negative affective engagement influences high involvement CSB.

H3c(ii): Negative affective engagement influences low involvement CSB.

Conative engagement and charity support behaviours

Customer engagement is recognised as the investment of (cognitive, affective, and conative) resources in interactions beyond transactions towards the focal object (Hollebeek et al. 2019). Therefore, when an individual is engaged with an idea or a cause, this translates to conative resource investment into the idea or cause as the focal object (Sim and Plewa 2017). Conation refers to the connection of knowledge (cognition) and affect to behaviour. It is a personal, deliberate, goal-oriented, and volitional aspect of behaviour (Baumeister et al. 1998). In the context presented in this research, we consider a scenario where the individual is willing to invest conative resources into the issue of homelessness through reading or other activities related to the social issue.

Engagement is contextually determined, and its intensity and valance are dependent on the situation in which it occurs and the focal object to which the engagement is directed (Brodie et al. 2011; Sim and Plewa 2017). Engagement research also shows that engagement with the focal object can spill over to engagement with other focal objects associated with the brand (Bowden et al. 2017). Further, research on cause-related marketing suggests that attitudes towards the cause are often transferred to the brand (Bergkvist and Zhou 2019) or the organisation; this is key in the context and knowledge development of this research. Initial conative engagement related to a particular social issue (e.g. homelessness) can become the seed of further prosocial (for instance, charity support) behaviours. Therefore, it is argued here that individuals prepared to offer behavioural resource (conative engagement) towards the cause are also likely to exhibit behavioural support for the brand (i.e. the charity) through charity support behaviours. We therefore propose:

H3d(i): Conative engagement positively influences high involvement CSB.

H3d(ii): Conative engagement positively influences low involvement CSB.

Method

Research context and sample

Homelessness was chosen as a context for this research as it is a contemporary global problem and is a focal point for many not-for-profit organisations, local action, social movements, community, and individual projects. The story of one of the beneficiaries of an organisation helping people experiencing homelessness is used in this study.

A quantitative online survey with closed-ended scale responses was constructed and administered using an online panel provider, Qualtrics. Respondents, drawn from the online panel, represented a general Australian population sample over 18 and under 75 years of age. To avoid bias, responses from not-for-profit organisations workers were excluded. The respondents were 53% female and 47% male and represented all age categories between 18 and 75 years. 52.8% of respondents completed tertiary education. The data is comparable to the population distribution of Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020, 2019).

In Scenario 1, before completing the survey, participants were asked to read a true story of a person experiencing homelessness, one of the beneficiaries of the organisation. 84% of participants declared no personal experience with homelessness, and 87.7% were unfamiliar with the organisation mentioned in the story. 41.3% of respondents declared supporting charity every few months, and 24.8%—once a year or less. The number of responses (n = 455) is considered sufficient for the chosen method (Delice 2010). To provide a comparison not exposed to a story, a smaller sample of participants were asked to read a general text about homelessness, based on facts and without a story narrative (Scenario 2). 88.5% of participants declared no personal experience with homelessness, and 89.2% were unfamiliar with the organisation. 40% of respondents declared supporting charity every few months, and 26.2%—once a year or less. 130 usable responses were obtained. See Appendix A for an example of the story (Scenario 1) and the general text (Scenario 2).

Data collection

A quantitative method using an online survey and structural equation modelling were used to examine relations between observed variables. The survey was constructed using existing measurement scales adapted to fit the research context. Transportation scale (Green and Brock 2000), customer brand engagement scale (Hollebeek et al. 2014), and a typology of charity support behaviours (Peloza and Hassay 2007) were used to measure respectively: narrative transportation, customer engagement, and charity support behaviours.

Due to the study context and the fact that the self-reported responses to an online survey were collected, the data could have become the subject of a potential bias. To limit social desirability bias, both direct (such as anonymity and confidentiality assurances) and indirect (face-saving alternatives in answer options for selected questions; for instance, about the experience related to homelessness) measures were used (Larson 2019). Common method bias was addressed through procedural measures by adding an interrupting question to reduce participants’ tendency to use previous answers to inform subsequent answers, protecting anonymity of responses, reducing the risk of pattern responses through careful survey design, using alternating scale formats, and reversed items (Podsakoff et al. 2012). Two different techniques were used to address the potential common method variance. Harman’s single factor test was applied and the total variance explained by the single factor met the criterion < 50% (39.448% in Scenario 1, and 36.511% in Scenario 2) (Kock 2021). However, since it is not the most stringent method of common method bias detection (Podsakoff et al. 2003), the variance inflation factors (VIF) were also considered (Kock 2015). Considering the complexity of the statistical model, the VIF threshold of 5 was employed (Kock and Lynn 2012), and this criterion was met for all the variables, confirming that data were not contaminated by common method bias.

Data analysis was applied using the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), which allows for estimating complex relationship models with latent variables (Latan and Noonan 2017). Respondents were informed about anonymity and the possibility to withdraw at any point of the survey. The quality of the responses (patterns, failure in quality checks, participants outside the targeted sample) was ensured by the panel provider and additionally assessed by analysis in terms of sample representativeness. The timing was used for some of the questions to ensure that respondents had enough time to complete the question. As reading the text was a vital part of the study, participants were alerted to the need to spend sufficient time on a question containing the text. Figures 2 and 3 show the statistical models for Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 with path coefficients and R2 for analysed variables and relations between them (Table 1).

Data analysis

All constructs were rigorously assessed using SmartPLS 3, and were found to be reliable, applying rigorous scale purification, including minimum loading of items of 0.7 and composite reliability scores in the range of 0.895–0.967 (Scenario 1) and of 0.880–0.976 (Scenario 2) (Fornell and Larcker 1981). As a result of this step, the high involvement CSB and low involvement CSB scales are not asymmetrical, an indication that low involvement CSB was constituted from fewer support behaviours than high involvement CSB. This does not compromise items’ predictive validity performance (Diamantopoulos et al. 2012). Discriminant validity was assessed using the HTMT matrix (Henseler et al. 2015) and evaluated until all HTMT rations met the 0.9 criterion (see Tables 2 and 3). Additionally, all average variances extracted (AVE) exceeded the squared correlations (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Collinearity among latent variables was assessed with VIF scores for each indicator less than the critical value of 10 (Hair et al. 2019), with the highest value being 4.577 in Scenario 1 and 5.677 in Scenario 2.

Results

Scenario 1

Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed to identify the relations between the key constructs within the conceptual model. The hypotheses were assessed through prediction accuracy (R2, adjusted R2) and predictive relevance (Q2) of exogenous constructs in the path model. To test the model in terms of the impact of narrative transportation on engagement, and narrative transportation and engagement on charity support behaviours, the coefficient of determination (R2) was examined and found to have satisfactory predictive accuracy (Hair et al. 2019) (see Table 4). The Q2 values, indicating predictive relevance of the structural model, were greater than 0 (except for the influence of conative engagement on low involvement charity support behaviours) and showed adequate predictive validity (Hair et al. 2019; Henseler et al. 2015).

The strength of the relations and individual effects of exogenous constructs were investigated by means of paths coefficients and their significance levels (Table 5).

First, the results showed that narrative transportation played a significant role in evoking engagement across all dimensions. The direct effects of narrative transportation on cognitive engagement (β = 0.763, p < 0.001), positive affective engagement (β = 0.407, p < 0.001), negative affective engagement (β = 0.493, p < 0.001), and conative engagement (β = 0.493, p < 0.001) were significant, supporting hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c, H1d.

Second, the direct effects of narrative transportation on high involvement CSB (β = 0.320, p < 0.001) was significant, supporting hypothesis H2a. However, the direct effect of narrative transportation on low involvement CSB (β = 0.120, p > 0.001) was nonsignificant, and hypothesis H2b was not supported.

Third, the impact of engagement on high and low involvement charity support behaviours varied across individual dimensions. Cognitive engagement positively and significantly influenced both high involvement CSB (β = 0.157, p < 0.05), supporting hypothesis H3a(i), and low involvement CSB (β = 0.383, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H3a(ii). Both positive and negative affective engagement proved to be predictors of low involvement CSB; their impact on high involvement CSB was insignificant. The direct effects of positive (β = 0.021, p > 0.05) and negative (β = 0.087, p > 0.05) affective engagement on high involvement CSB were nonsignificant, and hypotheses H3b(i) and H3c(i) were not supported. The direct effects of positive (β = 0.115, p < 0.05) and negative affective engagement (β = 0.167, p < 0.001) on low involvement CSB were significant, and the hypotheses H3b(ii) and H3c(ii) were supported. Conative engagement influenced both high and low involvement CSB. The direct positive effect of conative engagement on high involvement CSB (β = 0.263, p < 0.001) was significant, and hypothesis H3d(i) was supported. The direct negative effect of conative engagement on low involvement CSB (β = − 0.154, p < 0.05) was significant, and the hypothesis H3d(ii) was not supported.

Scenario 2

The same approach was taken as in Scenario 1 (see Tables 6 and 7).

First, narrative transportation proved to play an important role in evoking engagement in all its dimensions. The direct effects of narrative transportation on cognitive engagement (β = 0.666, p < 0.001), negative affective engagement (β = 0.647, p < 0.001), and conative engagement (β = 0.419, p < 0.001) were significant, supporting hypotheses H1a, H1c, H1d. The exception was the impact of narrative transportation on positive affective engagement, where the direct negative effect (β = − 0.010, p > 0.05) was nonsignificant, and hypothesis H1b was not supported.

Second, the results showed that the direct effect of narrative transportation on high involvement CSB (β = 0.292, p < 0.05) was significant, supporting hypothesis H2a. However, the direct effect of narrative transportation on low involvement CSB (β = 0.069, p > 0.001) was nonsignificant, and hypothesis H2b was not supported.

Third, there were differences in the impact of engagement on high and low involvement charity support behaviours in its individual dimensions. Cognitive engagement positively influenced only low involvement CSB. The direct effect of cognitive engagement on high involvement CSB (β = 0.002, p > 0.05) was nonsignificant, and hypothesis H3a(i) was not supported. The direct effect of cognitive engagement on low involvement CSB (β = 0.419, p < 0.05) was significant, and hypothesis H3a(ii) was supported. The impact of both positive and negative affective engagement on low involvement CSB was insignificant. The direct effects of positive (β = − 0.028, p > 0.05) and negative (β = 0.184, p > 0.05) affective engagement on low involvement CSB were nonsignificant, and hypotheses H3b(ii) and H3c(ii) were not supported. Although the direct effect of positive affective engagement on high involvement CSB (β = 0.015, p > 0.05) was nonsignificant (hypothesis H3b(i) was not supported), negative affective engagement was shown to as an important predictor of high involvement CSB. The direct effect (β = 0.277, p < 0.05) was significant, and hypothesis H3c(i) was supported. Conative engagement influenced high involvement charity support behaviours. The direct positive effect of conative engagement on high involvement CSB (β = 0.246, p < 0.05) was significant, and hypothesis H3d(i) was supported. The direct negative effect of conative engagement on low involvement CSB (β = − 0.158, p > 0.05) was nonsignificant, and hypothesis H3d(ii) was not supported. Table 8 shows the summary regarding hypotheses in both scenarios.

Discussion and implications

Research on storytelling in the context of charity support behaviours is fragmented, and empirical work on the behavioural outcomes of narrative transportation is particularly limited (van Laer et al. 2014). In an attempt to answer the question of how storytelling affects charity support behaviours, we looked at both the role of narrative transportation and customer engagement. The obtained results bring several theoretical and practical contributions.

Theoretical contribution

This study responds to a call for research on the behavioural effects of narrative transportation (van Laer et al. 2014), and investigates both direct and indirect effects on charity support behaviours. Results confirm the direct influence of narrative transportation on high involvement (cause-driven) charity support behaviours, contributing to theory in this area. Although studies on the behavioural results of narrative transportation have shown an indirect effect on health-related behaviour (Gebbers et al. 2017) or measurable effects related to energy saving and climate change (van Laer and Gordon 2017), our studies are the first to confirm a direct impact on prosocial, cause-oriented charity support behaviours. This is especially important in terms of understanding the mechanisms triggering the desired actions to the growing realm of cause-related marketing.

Further, this study links narrative transportation and customer engagement and thus considers the interplay of two types of engagement: engagement with the story and engagement with the cause it concerns. Although affective and cognitive aspects of narrative transportation have previously been considered in parallel with the dimensions of engagement, we emphasise the distinctiveness of the focal objects of these constructs. Considering narrative transportation as a potential antecedent of customer engagement (Brodie et al. 2011), we investigated the relationship between them and their importance in storytelling for prosocial outcomes. The results confirm the mediating role of customer engagement with the cause in the narrative transportation—charity support behaviours relationship. Consideration of the various dimensions of customer engagement demonstrates a significant enhancing role in using narrative transportation to provoke charity support behaviours; this contributes to knowledge in the fields of both storytelling and customer engagement. Different cognitive, affective, and conative pathways show that the independent effects of each dimension of customer engagement should be considered (Conduit et al. 2019).

The cognitive path of storytelling’s influence (through cognitive customer engagement with the cause) on charity support behaviours was the most influential. This is in line with the notion that the essential determinants of human motivation are knowledge, perceived self-efficacy, and expectations about results (Bandura 2004). Respondents who were exposed to the story scenario (i.e. read the story) declared both high and low involvement charity support behaviours. In contrast, among the respondents exposed to the informative text scenario, without additional factors related to the story: story-consistent beliefs (Green 2014; Marsh and Fazio 2006; van Laer et al. 2014) and narrative thoughts (Chang 2009; van Laer et al. 2014), only the path leading through cognitive engagement with the cause to low involvement CSB was significant. It should be noted that the influence of narrative transportation on cognitive engagement was more significant in the story scenario (Scenario 1) than in the no-story scenario (Scenario 2), supporting previous findings that narrative transportation reduces counterarguing (Nabi and Green 2015; Slater and Rouner 2002). The still strong influence of narrative transportation on cognitive engagement in the no-story scenario (Scenario 2) is in line with the claim that the reduction of critical thoughts may depend on the strength of the presented facts (Krause and Rucker 2020). The strength of arguments in non-narratives can prove to be persuasive to a similar degree as the use of narrative (Lien and Chen 2013).

Despite the significant influence of storytelling and narrative transportation on affective engagement (in line with findings of Chang (2009); Lamarre and Landreville (2009)), its further direct impact on prosocial behaviour is not particularly strong. This would confirm Ajzen (2011) approach that emotions serve as a foundation supporting beliefs or a catalyst for already established norms, not as a primary driver. Affective engagement (both positive and negative) prompted the respondents reading the story (Scenario 1) to declare a willingness to undertake low involvement charity support behaviours. This may result from a sense of lack of control or the ability to face a social problem presented in the story and a perception of cause-driven actions as impossible due to potentially too high emotional costs. While narrative transportation did not elicit positive affective engagement in the no-story scenario (Scenario 2), it substantially impacted its negative sub-dimension. It was also the only affective path leading to high involvement CSB. This finding confirms the study by Greenbaum et al. (2020) that negative emotional responses can lead to prosocial behaviour as corrective actions to change a morally disturbing situation and/or support the victim.

The impact of narrative transportation on conative engagement was significant for both scenarios. In both cases, it led to high involvement CSB, which, as cause-driven, seem to be a natural consequence of such engagement. This is consistent with research on intentions to share information (Dolan et al. 2019; Kang et al. 2020), where rational, informative content influenced the active engagement behaviour. Attitudes do not always have predictive power for actual action due to the spatial and temporal discrepancy between self-reported intentions and real actions (Trope and Liberman 2010). However, the significant conative path suggests that this dimension of engagement may also bring results in the form of charity support behaviours. This is in line with studies showing that engagement with one focal object (e.g. homelessness) can spread into engagement with other focal objects (e.g. not-for-profit organisations) (Bowden et al. 2017; Conduit et al. 2016) and that attitudes towards the cause are often transferred to the brand or organisation (Bergkvist and Zhou 2019). It is worth emphasising the negative relationship of conative engagement with low involvement charity support behaviours (significant in Scenario 1), as such behaviours are not facilitated by engagement with the cause, rather they result from evaluation of costs and benefits (Hess and Story 2005) than from a real engagement with the social problem raised in the text (Peloza and Hassay 2007).

The introduction of a negative sub-dimension of affective engagement, an approach often overlooked in customer engagement research (Naumann et al. 2020), made it possible to discover an additional pathway of the influence of narrative transportation on CSB in the no-story scenario (Scenario 2). Although the impact of negative emotions on prosocial behaviour was previously considered (Greenbaum et al. 2020), the analysis of negative affective engagement as a factor enhancing the impact of narrative transportation on charity support behaviours is, as far as we know, the first such study. Customer engagement literature considers negatively valenced affective engagement (Naumann et al. 2017); however did not explore its positive effects, crucial in the prosocial context (Naimi et al. 2023). The inclusion of a contrasting negative affective engagement could uncover several alternative pathways as it has done here by showing its effects on charity support behaviours as potential actions changing the situation provoking these negative emotional responses.

The analysis of high and low involvement charity support behaviours as engagement with the charity resulting from engagement with the cause reflects the spillover effect between two focal objects (Bowden et al. 2017) and addresses the call for studies exploring these effects (Hollebeek et al. 2023) and contributes to customer engagement literature. High involvement CSB can result from cognitive and conative engagement with the cause presented in the story and supported by the charity. Affective (both positive and negative) engagement with the cause led only to low involvement CSB, related to value-driven motives, with little to no consideration for the charity that supports this cause. Supporters’ loyalty towards a brand, a charity, an organisation can be achieved by eliciting cognitive and conative engagement with the associated cause. Emotional appeals still bring engagement with the cause and charity support behaviours; however, they do not guarantee closer ties with the charitable brand or organisation, as indicated by the lack of impact on high involvement CSB.

In conclusion, we have considered the combined effects of narrative transportation and customer engagement to show how they interdependently facilitate charity support behaviours. Significant effects of all the dimensions of customer engagement with the cause illustrate its effects as a mediator in the narrative transportation-charity support behaviours relationship, albeit the different effects of the dimensions confirm that this construct should be considered multidimensionally. The negative sub-dimension of affective engagement has brought new insight into narrative transportation’s potential use to provoke expected behaviour. The results do not support the claim that emotional mechanisms are responsible for helping identified victims (Lee and Feeley 2016) (like in Scenario 1), while supporting statistical victims (as portrayed in Scenario 2) is based on cognitive mechanisms (Kossowska et al. 2020)—the relationships governing human motivations to help are more complex. The varying dimensions of customer engagement with the cause, impact on whether high involvement or low involvement CSB eventuate. Although high involvement charity support behaviours are often considered of greater importance, CSB caused by other reasons should not be ignored. They may become an introduction to the charity and ultimately lead to greater engagement and subsequent support (Peloza and Hassay 2007). Hence, there is a need to consider the interplay of narrative transportation with each dimension of customer engagement to determine the desired effects on CSB.

Managerial implications

First, both the story and the informative text led to narrative transportation (engagement with the story); however, its impact on the individual dimensions of engagement (with the cause) and then on charity support behaviours (engagement with the charity) differed, which is crucial for guidelines for organisations with a prosocial profile. If organisations want people to respond with CSB motivated by the idea of helping, altruism (for the benefit of others) rather than mutualism (for the benefit of both parties) (Wittek and Bekkers 2015), they should use stories to influence the audience. This is confirmed by the analyses of the cognitive and conative engagement paths.

The most significant difference between the story (Scenario 1) and no-story (Scenario 2) scenarios appeared in the engagement’s affective dimension. The story triggered positive affective engagement with the cause leading to low involvement CSB. In contrast, the informational text showed a strong influence on negative affective engagement (with the cause) leading to high involvement CSB. While playing on emotions seems risky, they appear to be powerful catalysts for human behaviour. If both positive and negative affective engagement with the cause results in supporting charity, organisations can use empathetic positive stories and facts that elicit moral objection as triggers. Negative emotions can turn into positive experiences when the recipient has the opportunity to help a person in need, for example, through a donation. This can help strengthen donors’ emotional payout and their future prosocial intentions (Merchant et al. 2010). A remedy for potential detrimental impact of negative emotional appeals could be sharing restorative stories, showing negative experiences but highlighting the meaningful improvement of a story character (Moore et al. 2021) to add a positive value to the outcomes of potential charity support behaviours.

Results show that using stories to convey the meaning and value of a charity brand or organisation and engage customers in loyal supporting behaviours should be based mainly on cognition. Although the affective path did not lead to cause-driven behaviours focused on a certain organisation, they can be considered a good starting point for building a stronger relationship with customers. They still bring benefits to the organisation, can help build a brand community (Hassay and Peloza 2009), and should not be ignored in brand communication.

Limitations and future research

We note that self-reported responses may be subject to response bias and increased error in reliability, but care was taken to reduce this risk as far as possible. We also recognise that an existing story leaves little space for changes and manipulation of the scenarios. The topic’s sensitivity remains not without significance when it comes to cognitive, emotional, and behavioural appeals and the responses to them. The study of other socially significant topics using the proposed model is strongly encouraged. Since most respondents admitted that they had supported charity in the past, research comparing with a group not yet involved in helping would be advisable, especially since non-intenders are driven by their awareness of and attitudes towards specific charity or cause (Nguyen et al. 2022). Future research into dimensions of narrative transportation would help explore its effects in more detail. An analysis of the specific types of emotions accompanying the story reception would allow more thorough insight into engagement’s affective pathways. An interesting avenue for future studies also seems to be the influence of storytelling on altruistic intentions and prosocialness as a disposition to behave in a certain way. The use of different types of narrative (for example, different narrative points of view) or other media to communicate information may prove interesting for the clues of story creation and co-creation. Moreover, since repeated exposure to the same story (bedtime stories, narrative advertisements, organisational and brand stories) influences the recipient’s self-efficacy and thus supports the narrative transportation effect (Bandura 2004), future research might explore the impact of the re-experienced narratives on story-consistent behaviours. Although branded storytelling impacts customer engagement (Dessart and Pitardi 2019), customer brand storytelling (as compared to a firm-created brand story) can lead to more favourable brand attitudes (Hong et al. 2021). Such a co-creative approach should be explored by both researchers and practitioners.

Building on the acknowledged limitations of this research and the complexity of the analysed processes, the potential paths for further exploration form three main trends: factors on the storyteller side, those related to the audience, and the range of elements on the border of these two worlds. While addressing the challenge of extending the framework outlined by van Laer et al. (2014), this research focused on the customers’ journey through multifaceted engagement with three focal objects: the story, the cause, and the charity to examine the mechanisms of storytelling’s impact on charity support behaviours.

References

Ajzen, Icek. 2011. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychology & Health 26 (9): 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995.

Appel, Markus. 2022. Affective Resistance to Narrative Persuasion. Journal of Business Research 149: 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.05.001.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2019. Regional Population by Age and Sex. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2020. Education and Work, Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Bal, P. Matthijs., and Martijn Veltkamp. 2013. How Does Fiction Reading Influence Empathy? An Experimental Investigation on the Role of Emotional Transportation. PLoS ONE 8 (1): e55341–e55341. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055341.

Bandura, Albert. 2004. Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means. Health Education & Behavior 31 (2): 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660.

Barraza, Jorge A., Veronika Alexander, Laura E. Beavin, Elizabeth T. Terris, and Paul J. Zak. 2015. The Heart of the Story: Peripheral Physiology During Narrative Exposure Predicts Charitable Giving. Biological Psychology 105: 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.01.008.

Baumeister, Roy F., Ellen Bratslavsky, Mark Muraven, and Dianne M. Tice. 1998. Ego Depletion: Is the Active Self a Limited Resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74 (5): 1252–1265. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1252.

Ben Youssef, K., T. Leicht, and L. Marongiu. 2019. Storytelling in the Context of Destination Marketing: An Analysis of Conceptualisations and Impact Measurement. Journal of Strategic Marketing 27 (8): 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2018.1464498.

Bendapudi, Neeli, Surendra N. Singh, and Venkat Bendapudi. 1996. Enhancing Helping Behavior: An Integrative Framework for Promotion Planning. Journal of Marketing 60 (3): 33–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251840.

Bennett, Roger. 2003. Factors Underlying the Inclination to Donate to Particular Types of Charity. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 8 (1): 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.198.

Bennett, Roger. 2013. Elements, Causes and Effects of Donor Engagement Among Supporters of UK Charities. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 10 (3): 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-013-0100-1.

Bergkvist, Lars, and Kris Qiang Zhou. 2019. Cause-Related Marketing Persuasion Research: An Integrated Framework and Directions for Further Research. International Journal of Advertising 38 (1): 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1452397.

Chattoo, Borum, and Caty, and Lauren Feldman. 2017. Storytelling for Social Change: Leveraging Documentary and Comedy for Public Engagement in Global Poverty: Storytelling for Social Change. Journal of Communication 67 (5): 678–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12318.

Boukes, Mark, and Heather L. LaMarre. 2021. Narrative Persuasion by Corporate CSR Messages: The Impact of Narrative Richness on Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions via Character Identification, Transportation, and Message Credibility. Public Relations Review 47 (5): 102107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102107.

Bowden, Jana Lay-Hwa., Jodie Conduit, Linda D. Hollebeek, Vilma Luoma-aho, and Birgit Apenes Solem. 2017. Engagement Valence Duality and Spillover Effects in Online Brand Communities. Journal of Service Theory and Practice 27 (4): 877–897. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-04-2016-0072.

Brodie, Roderick J., Linda D. Hollebeek, Biljana Jurić, and Ana Ilić. 2011. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. Journal of Service Research 14 (3): 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703.

Bublitz, M.G., J.E. Escalas, L.A. Peracchio, P. Furchheim, S.L. Grau, A. Hamby, M.J. Kay, M.R. Mulder, and A. Scott. 2016. Transformative Stories: A Framework for Crafting Stories for Social Impact Organizations. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 35 (2): 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.15.133.

Burke, Miriam, David Ockwell, and Lorraine Whitmarsh. 2018. Participatory Arts and Affective Engagement with Climate Change: The Missing Link in Achieving Climate Compatible Behaviour Change? Global Environmental Change 49: 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.02.007.

Carnevale, Marina, Ozge Yucel-Aybat, and Luke Kachersky. 2018. Meaningful Stories and Attitudes Toward the Brand: The Moderating Role of Consumers’ Implicit Mindsets. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 17 (1): e78–e89. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1687.

Chang, Chingching. 2009. “Being Hooked” By Editorial Content: The Implications for Processing Narrative Advertising. Journal of Advertising 38 (1): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367380102.

Chen, Tsai, and Hui-Chen. Chang. 2017. The Effect of Narrative Transportation in Mini-film Advertising on Reducing Counterarguing. International Journal of Electronic Commerce Studies 8 (1): 25–47. https://doi.org/10.7903/ijecs.1476.

Choi, Jungsil, Yexin Jessica Li, Priyamvadha Rangan, Bingqing Yin, and Surendra N. Singh. 2020. Opposites Attract: Impact of Background Color on effectiveness of Emotional Charity Appeals. International Journal of Research in Marketing 37 (3): 644–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2020.02.001.

Coker, Kesha K., Richard L. Flight, and Dominic M. Baima. 2021. Video Storytelling Ads vs Argumentative Ads: How Hooking Viewers Enhances Consumer Engagement. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 15 (4): 607–622. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-05-2020-0115.

Cole, Courtney E. 2010. Problematizing Therapeutic Assumptions About Narratives: A Case Study of Storytelling Events in a Post-Conflict Context. Health Communication 25 (8): 650–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2010.521905.

Conduit, Jodie, Ingo O. Karpen, and Francis Farrelly. 2016. Student Engagement: A Multiple Layer Phenomenon. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Conduit, Jodie, Ingo Oswald Karpen, and Kieran D. Tierney. 2019. Volunteer Engagement: Conceptual Extensions and Value-in-Context Outcomes. Journal of Service Theory and Practice 29 (4): 462–487. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-06-2018-0138.

Correa, Kelly A., Bradly T. Stone, Maja Stikic, Robin R. Johnson, and Chris Berka. 2015. Characterizing Donation Behavior from Psychophysiological Indices of Narrative Experience. Frontiers in Neuroscience 9: 301–301. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00301.

Cin, Dal, Bryan Gibson Sonya, Mark P. Zanna, Roberta Shumate, and Geoffrey T. Fong. 2007. Smoking in Movies, Implicit Associations of Smoking With the Self, and Intentions to Smoke. Psychological Science 18 (7): 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01939.x.

Davis, Mark H. 1983. Measuring Individual Differences in Empathy: Evidence for a Multidimensional Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 (1): 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113.

Delice, Ali. 2010. The Sampling Issues in Quantitative Research. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri 10 (4): 2001–2018.

Dessart, Laurence, and Valentina Pitardi. 2019. How Stories Generate Consumer Engagement: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Research 104: 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.045.

Dessart, Laurence, Cleopatra Veloutsou, and Anna Morgan-Thomas. 2015. Consumer Engagement in Online Brand Communities: A Social Media Perspective. Journal of Product and Brand Management 24 (1): 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2014-0635.

Diamantopoulos, A., M. Sarstedt, S. Christoph Fuchs, and Kaiser, and P. Wilczynski. 2012. Guidelines for Choosing between Multi-Item and Single-Item Scales for Construct Measurement: A Predictive Validity Perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 40 (3): 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3.

Dolan, R., J. Conduit, C. Frethey-Bentham, J. Fahy, and S. Goodman. 2019. Social Media Engagement Behavior: A Framework for Engaging Customers Through Social Media Content. European Journal of Marketing 53 (10): 2213–2243. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2017-0182.

Dunlop, William L. 2022. The Cycle of Life and Story: Redemptive Autobiographical Narratives and Prosocial Behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology 43: 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.019.

Escalas, Jennifer, Marian Moore Edson, and Chapman, and Julie Britton, Edell. 2004. Fishing for Feelings? Hooking Viewers Helps. Journal of Consumer Psychology 14 (1): 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1401&2_12.

Faulkner, Margaret, and Jenni Romaniuk. 2019. Supporters’ Perceptions of Benefits Delivered by Different Charity Activities. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 31 (1): 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2018.1452829.

Fenton, Jennifer Kiefer. 2021. Storied Social Change: Recovering Jane Addams’s Early Model of Constituent Storytelling to Navigate the Practical Challenges of Speaking for Others. Hypatia 36 (2): 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2021.19.

Fishbein, Martin, and Marco C. Yzer. 2003. Using Theory to Design Effective Health Behavior Interventions. Communication Theory 13 (2): 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x.

Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312.

Ganassali, Stéphane., and Justyna Matysiewicz. 2021. Echoing the Golden Legends: Storytelling Archetypes and Their Impact on Brand Perceived Value. Journal of Marketing Management 37 (5–6): 437–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1831577.

Gebbers, Timon, J.B.F. de Wit, and Markus Appel. 2017. Transportation into Narrative Worlds and the Motivation to Change Health-Related Behavior. International Journal of Communication 11: 4886–4906.

Gerrig, Richard J. 1993. Experiencing Narrative Worlds. On the Psychological Activities of Reading. Yale University Press.

Green, M. C. 2014. "Transportation into narrative worlds: The role of prior knowledge and perceived realism." In The Effects of Personal Involvement in Narrative Discourse: A Special Issue of Discourse Processes, 247–266. Taylor and Francis.

Green, M.C., and T.C. Brock. 2000. The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79 (5): 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701.

Green, Melanie C. 2004. Transportation into Narrative Worlds: The Role of Prior Knowledge and Perceived Realism. Discourse Processes 38 (2): 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326950dp3802_5.

Green, Melanie C. 2008. Transportation Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Chichester: Wiley.

Green, Melanie C., and Timothy C. Brock. 2002. "In the mind's eye: Transportation-imagery model of narrative persuasion." In Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations., 315–341. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Green, Melanie C., Sheryl Kass, Jana Carrey, Benjamin Herzig, Ryan Feeney, and John Sabini. 2008. Transportation Across Media: Repeated Exposure to Print and Film. Media Psychology 11 (4): 512–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802492000.

Greenbaum, Rebecca, Julena Bonner, Truit Gray, and Mary Mawritz. 2020. Moral Emotions: A Review and Research Agenda for Management Scholarship. Journal of Organizational Behavior 41 (2): 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2367.

Gregory, W. Larry., Robert B. Cialdini, and Kathleen M. Carpenter. 1982. Self-relevant Scenarios as Mediators of Likelihood Estimates and Compliance: Does Imagining Make It so? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 43 (1): 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.1.89.

Gross, James J. 2002. Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences. Psychophysiology 39 (3): 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577201393198.

Guo, Q., P. Sun, M. Cai, X. Zhang, and K. Song. 2019. Why Are Smarter Individuals More Prosocial? A Study on the Mediating Roles of Empathy and Moral Identity. Intelligence 75: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2019.02.006.

Hair, Joseph F., Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. 2019. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31 (1): 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203.

Hansen, Thomas, and Britt Slagsvold. 2020. An “Army of Volunteers”? Engagement, Motivation, and Barriers to Volunteering Among the Baby Boomers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 63 (4): 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1758269.

Harp, Elizabeth R., Lisa L. Scherer, and Joseph A. Allen. 2017. Volunteer Engagement and Retention: Their Relationship to Community Service Self-Efficacy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 46 (2): 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016651335.

Hassay, Derek N., and John Peloza. 2009. Building the Charity Brand Community. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 21 (1): 24–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495140802111927.

Henseler, Jörg., Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2015. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 (1): 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

Herrera, Fernanda, Jeremy Bailenson, Erika Weisz, Elise Ogle, and Jamil Zak. 2018. Building Long-Term Empathy: A Large-Scale Comparison of Traditional and Virtual Reality Perspective-Taking. PLoS ONE 13 (10): e0204494–e0204494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204494.

Hess, Jeff, and John Story. 2005. Trust-Based Commitment: Multidimensional Consumer-Brand Relationships. The Journal of Consumer Marketing 22 (6): 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760510623902.

Hollebeek, Linda D., and Tom Chen. 2014. Exploring Positively- Versus Negatively-Valenced Brand Engagement: A Conceptual Model. Journal of Product and Brand Management 23 (1): 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2013-0332.

Hollebeek, Linda D., Mark S. Glynn, and Roderick J. Brodie. 2014. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 28 (2): 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.12.002.

Hollebeek, Linda D., Viktorija Kulikovskaja, Marco Hubert, and Klaus G. Grunert. 2023. "Exploring a customer engagement spillover effect on social media: the moderating role of customer conscientiousness." Internet Research ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-08-2021-0619

Hollebeek, Linda, Rajendra Srivastava, and Tom Chen. 2019. S-D Logic-Informed Customer Engagement: Integrative Framework, Revised Fundamental Propositions, and Application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 47 (1): 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0494-5.

Hong, JungHwa, Jie Yang, Barbara Ross Wooldridge, and Anita D. Bhappu. 2021. "Sharing consumers’ brand storytelling: influence of consumers’ storytelling on brand attitude via emotions and cognitions." The Journal of product & brand Management ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2019-2485.