Abstract

In principle, the threat of partial or full revocation of the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) System’s charter by Congress should limit advances (collateralized loans) by FHLBs to member banks with high risks of failure that increase potential losses to the Deposit Insurance Fund. In practice, even as the risk of insolvency became apparent in the financial crisis, FHLBs renewed and in some cases increased lending to several large-bank members that eventually failed. We argue FHLBs continue to lend to large risky members both because the cooperative structure enables these banks to exert significant influence over their FHLBs, and because the risk of insolvency can be difficult to assess. Policy makers should consider regulatory or supervisory measures that limit the use of advances by large-bank members.

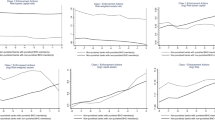

Sources: FFIEC Call Reports; FDIC Failed Bank List, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/individual/failed/banklist.html, accessed April 10, 2018

Sources: FFIEC Call Reports; FDIC Failed Bank List, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/individual/failed/banklist.html, accessed April 10, 2018; Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP)

Sources: FFIEC Call Reports; FDIC Failed Bank List, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/individual/failed/banklist.html, accessed April 10, 2018; Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP)

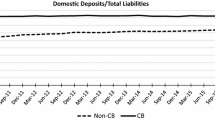

Source: FFIEC Call Reports

Source: FFIEC Call Reports

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Countrywide Financial Corporation. (2007) Form 10-Q for the quarterly period ended September 30, p. 30, accessed through S&P Capital IQ.

Schumer. C. (2007) Letter to Federal Housing Finance Board Chairman Ronald A. Rosenfeld. 26 November, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB119610390093704160. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

McKinley, V. 2014. Run, run, run: Was the financial crisis panic over institution runs justified? Cato Institute Policy Analysis 747: 1–36.

Bruck, C. (2018) Angelo’s Ashes: The man who became the face of the financial crisis. The New Yorker, 29 June, https://www.americanbanker.com/news/three-takeaways-from-the-seattle-des-moines-fhlb-merger. Accessed 5 Feb 2018.

Bennett, R.L., Vaughan, M.D., Yeager T.J. (2005) Should the FDIC Worry about the FHLB? The Impact of Federal Home Loan Bank Advances on the Bank Insurance Fund. FDIC Center for Financial Research Working Paper No. 2005-10. https://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/cfr/2005/wp2005/2005-10.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2018.

FDIC. (2017) Crisis and Response: An FDIC History, 2008–2013, https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/crisis, accessed 27 May 2018. Wachovia informed the OCC on September 26, 2008 that it would be unable to obtain the funds needed to pay creditor claims on September 29. On that day, the FDIC Board and the Federal Reserve Board recommended invoking the Systemic Risk Exception (SRE) for the first time, which would allow Citigroup to acquire Wachovia. However, Wells Fargo subsequently made a successful bid for Wachovia that negated the need for the SRE.

The number of FHLBs is now 11 after the merger of the Seattle and Des Moines FHLBs in 2015.

Ashcraft, A., M.L. Bech, and W.S. Frame. 2010. The federal home loan bank system: The lender of next-to-last resort? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42 (4): 551–583.

Nickerson, D., Phillips, R. J. (2002) Financial Déjà vu? The Farm Credit System’s Past Woes Could Strike the Federal Home Loan Bank System. Regulation. Spring: 40–45.

U.S. Code § 1442—Member financial information. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title12/pdf/USCODE-2010-title12-chap11-sec1442.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Ashley, L.K., E. Brewer, and N.E. Vincent. 1998. Access to FHL Bank advances and the performance of thrift institutions. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Economic Perspectives 22: 33–52.

Martinez, J., and Q. Li. 2011. Community Banks use of FHLB advances across the Kansas City (KC) and San Francisco (SF) Federal Reserve Districts. Southwestern Economic Review 38: 73–92.

Flannery, M.J., and W.S. Frame. 2006. The Federal Home Loan Bank system: the ‘other’ housing GSE, 33–54. Third Quarter: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review.

Stojanovic, D., M.D. Vaughan, and T.J. Yeager. 2008. Do Federal Home Loan Bank Membership and Advances Increase Bank Risk-Taking? Journal of Banking & Finance 32: 680–698.

Frame, W.S., and L.J. White. 2011. The Federal Home Loan Bank System: Current issues in perspective. In Reforming rules and regulations, ed. V. Ghosal, 255–276. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Maloney, D.K. and Thompson, J.B. (2003) The Evolving Role of the Federal Home Loan Banks in Mortgage Markets. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary, June.

Davidson, T., and W.G. Simpson. 2016. Federal Home Loan Bank Advances and Bank Risk. Journal of Economics and Finance 40 (1): 137–156.

The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 abolished the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and established the Federal Housing Finance Board (FHFB) to regulate the FHLBs. The Bank Board’s supervisory responsibilities over thrift institutions were transferred to the newly established Office of Thrift Supervision.

FHLB Office of Finance. (2018) Lending and Collateral Q&A, http://www.fhlb-of.com/ofweb_userWeb/resources/lendingqanda.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2018.

Under Section 29 of the FDI Act an undercapitalized insured depository institution may not accept, renew, or roll over any brokered deposit. An adequately capitalized insured depository institution may not accept, renew, or roll over any brokered deposit unless the institution has applied for and been granted a waiver by the FDIC.

Collins, B. (2015) Three Takeaways from the Seattle-Des Moines FHLB Merger. American Banker, 9 June, https://www.americanbanker.com/news/three-takeaways-from-the-seattle-des-moines-fhlb-merger. Accessed 5 Feb 2018.

Translation of fields between TFR and Call Reports is based on documentation provided by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which assumed responsibility for thrift supervision in July 2011.

Cole, R., J. Gunther, and B. Cornyn. 1995. FIMS: A new financial institutions monitoring system for banking organizations. Federal Reserve Bulletin 81: 1–15.

Miller, S., E. Olson, and T. Yeager. 2015. The Relative Contributions of Equity and Subordinated Debt Signals as Predictors of Bank Distress during the Financial Crisis. Journal of Financial Stability 16: 118–137.

Merton, R.C. 1974. On the Pricing of Corporate Debt: The Risk Structure of Interest Rates. Journal of Finance 29: 449–470.

Crosbie, P. and Bohn, J. (2003) Modeling Default Risk. Moody’s KMV Company, 9 December, https://business.illinois.edu/gpennacc/MoodysKMV.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2018.

Federal Home Loan Bank Des Moines. (2011) Credit and Collateral Procedure Changes. Announcements, 2 June, https://www.fhlbdm.com/media/cms/Credit_and_Collateral_Announcement__FCBBD9EBD9F91.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2018.

All references to “failed” or “failing” banks include those that received FDIC open-bank assistance, which consisted of loss guarantees on asset pools. Citigroup’s subsidiaries received assistance in the fourth quarter 2008, and Bank of America’s subsidiaries (including Countrywide Bank) received assistance in the first quarter of 2009.

In Panel A of Figure 3, the $23.7 billion decline in advances one quarter prior to failure was mainly the result of a $20.7 billion decline in advances at the Bank of America in the fourth quarter of 2008, the same quarter the bank received $15 billion in TARP funds.

King, T., D. Nuxoll, and T. Yeager. 2006. Are the Causes of Bank Distress Changing? Can Researchers Keep Up? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 88: 57–80.

Morgan, D. 2002. Rating Banks: Risk and Uncertainty in an Opaque Industry. The American Economic Review 92 (4): 874–888.

Jones, J., W. Lee, and T. Yeager. 2012. Opaque banks, price discovery, and financial instability. Journal of Financial Intermediation 21 (3): 383–408.

Flannery, M., S. Kwan, and M. Nimalendran. 2013. The 2007–2009 financial crisis and bank opaqueness. Journal of Financial Intermediation 22 (1): 55–84.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, (2006) Concentrations in Commercial Real Estate Lending Final Guidance, 12 December, https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/srletters/2007/SR0701a2.pdf. Accessed 7 June 2018.

FDIC-OIG. (2010) Material Loss Review of United Commercial Bank, San Francisco, California. MLR-10-043, July, https://www.fdicoig.gov/sites/default/files/publications/10-043.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2018.

FDIC-OIG. (2010) Material Loss Review of Colonial Bank, Montgomery, Alabama. MLR-10-031, April, https://www.fdicoig.gov/sites/default/files/publications/10-031.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2018.

Department of the Treasury-OIG. (2010) Material Loss Review of BankUnited FSB, OIG-10-042, June, https://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/ig/Documents/OIG10042%20(BankUnited%20MLR).pdf. Accessed 24 May 2018.

BankUnited Financial Corporation. (2008) Form 10Q Form 10-Q for the quarterly period ended 30 June, p. 38, accessed through S&P Capital IQ.

Office of Thrift Supervision. (2007) Report of Examination for Countrywide Bank FSB, 12 December, http://fcic-static.law.stanford.edu/cdn_media/fcic-docs/2007-12-12%20OTS%20Countrywide%20Report%20Of%20Examination%20Quarterly%20Target%20Reviews.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2018.

Garcia, G. (2010) Failing prompt corrective action, Journal of Banking Regulation 11:171–190. The author examines 50 MLRs between 2007 and 2009 and finds that 29 of them noted heavy reliance on FHLB advances.

FDIC-OIG. (2010) Material Loss Review of Imperial Capital Bank, La Jolla California, Report no. MLR-10-040, July, https://www.fdicoig.gov/sites/default/files/publications/10-040.pdf. Accessed 2 Apr 2018.

Department of the Treasury-OIG (2009) Material Loss Review of IndyMac Bank FSB, OIG-09-032, February, https://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/ig/Documents/oig09032.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

FDIC-OIG. (2009) Material Loss Review of FirstBank Financial Services, McDonough Georgia, AUD-09-024, January, https://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/ig/Documents/oig09024.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

FDIC estimate as of 31 December 2017.

FDIC. (2009) FDIC Board Approves Letter of Intent to Sell IndyMac Federal. Press release, 2 January, http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/press/2009/pr09001.html. Accessed 18 July 2018.

Federal Housing Finance Agency-OIG. (2012) FHFA’s Supervisory Framework for Federal Home Loan Banks’ Advances and Collateral Risk Management, AUD-2012-004, 1 June: 17–18, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/AUD-2012-004.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2018.

Federal Housing Finance Agency-OIG. (2012) FHFA’s Oversight of the Federal Home Loan Banks’ Unsecured Credit Risk Management Practices, EVL-2012-005, 28 June, https://www.fhfaoig.gov/Content/Files/EVL-2012-005_1_0.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

Gertler, M., Kiyotaki, N., Prestipino, A. (2016) Wholesale Banking and Bank Runs in Macroeconomic Modeling of Financial Crises. Board of Governors International Finance Discussion Papers 1156.

Government Accountability Office (2011) Bank Regulation: Modified Prompt Corrective Action Framework Would Improve Effectiveness, Report to Congressional Committees. GAO-11-612, June, https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d11612.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2018.

Peek, J., Rosengren, E. (1996) The Use of Capital Ratios to Trigger Interventions in Problem Banks: Too Little, Too Late, New England Economic Review, September/October: 49-58.

Jones, D., and K. King. 1995. The Implementation of Prompt Corrective Action: An Assessment. Journal of Banking & Finance 19: 491–510.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Acrey, J.C., Lee, W.Y. & Yeager, T.J. Can Federal Home Loan Banks effectively self-regulate lending to influential banks?. J Bank Regul 20, 197–210 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41261-018-0082-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41261-018-0082-3