Abstract

There are significant differences in the performance of Target Date Funds (TDFs) with the same target year. Using a unique dataset from Morningstar, we show that within the same target year, funds with lower than the average expense ratio, or higher than average allocation to equities, outperform similar funds. This outperformance exists across all target year groups and is economically meaningful. Furthermore, deviations in the equity allocation have a greater impact on performance than does expense ratio. Using bootstrap simulations to investigate the impact over a longer horizon, we show that deviations from the average allocations or expense ratios have a meaningful impact on the retirement savings of an average investor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“TDFs are often billed as ‘set it and forget it’ investments, yet expenses and risk allocations vary considerably among funds. The millions of families who trust their financial futures to target-date funds, need to know these programs are working as advertised and providing the retirement security promised,” wrote the Chairs.Footnote 1

TDFs with the same target retirement year can have completely different risk exposures and fund structures, potentially resulting in substantially different portfolio outcomes at retirement (28% difference based on expense ratio differences and 34% based on equity allocation differences, according to our simulations). There are no set standards on how TDFs of a particular target year should be managed. Recent lawsuits alleging ERISA fiduciary breach allegations of plan sponsors amplify the question of whether an investor can just “set it and forget it” and hope the retirement plan sponsor picks a winner.Footnote 2 In this paper, we provide evidence that this may be a very risky proposition for your retirement savings.

Starting in the mid-1990s, there was a significant shift in employer-sponsored retirement savings plans from defined benefits (DB) plans or so-called pension funds, to the now more popular defined contribution (DC) plans, commonly referred to as 401k plans. Unlike pension funds, which are managed solely by the employer; 401k plans (named after the IRS code) allow employees to have some control over how much they save for their retirement, and how their savings are allocated across different asset classes (and assets). While the introduction and increasing use of 401k plans served to address the rising costs of pension plans in the 1980s, they ushered in a new set of problems, foremost of which is requiring employees with limited knowledge of financial products to make investing decisions that could have long-term effects. There is a large literature that documents investment mistakes that individuals make in their retirement savings accounts (for examples, see Agnew 2006; Benartzi & Thaler 2007; and Huberman & Jiang 2006).

Target Date Funds (TDFs), also called Life-cycle funds were introduced primarily to simplify the options available to individuals, providing a pre-set mix of stocks, bonds and other assets that is appropriate for the individual’s age group. Even though the total assets in TDFs fell during the heart of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, as “of February 2021, target-date mutual funds held a record $1.6 trillion in assets.”Footnote 3 TDFs are constructed and named for a Target year, which is equivalent to the expected retirement year of the individual.

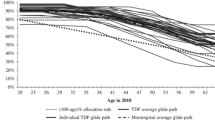

The basic premise behind the design of TDFs is that during investors’ early work life, when they are willing to be exposed to market swings, they will allocate a larger share of their retirement savings to more risky assets, i.e., equities. As the investor approaches retirement, the mix is progressively shifted from equities into more safe assets that provide a guarantee of a steady payout stream during the investor’s retirement years. In other words, individuals can achieve the benefits of diversification as well as re-balancing over their life-cycle, by choosing an age-appropriate TDF and forgetting about it until their retirement. Recent data published by Fidelity, a leading plan administrator, shows that currently “Ninety-five percent of active employees contribute to their 401(k)s…”. They also report that “two-thirds of millennials in Fidelity’s database are 100 percent invested in target date funds (TDFs).”Footnote 4 TDFs are also the most popular option in other individual retirement accounts.

Plan administrators provide information on fund performance, both on a real, as well as risk-adjusted basis. However, there is limited research on the efficacy of these products in achieving their intended goal. Furthermore, the assumption that funds within each target date group have similar return and risk profile has been largely untested. A recent exception is a study by Balduzzi & Reuter (2019) who show that there are great disparities in the realized return and risk of TDFs, even when the funds have the same target date and are therefore intended to meet the retirement needs of individuals expecting to reach retirement age within the same five-year period. In this paper, we perform an extensive investigation of the fund features that are related to under (and over) performance of funds within target date groups. We consider those fund characteristics that are largely within the manager’s control, i.e., the expense ratio and the percent allocated to different asset classes. We investigate how cross-sectional differences in these characteristics contribute to variability in fund performance both on a real as well as a risk-adjusted basis.

We make at least three important contributions to the literature on TDF performance. First, we use a unique dataset from Morningstar, which provides a comprehensive coverage of TDF funds and includes the detailed allocation of fund assets. This more granular dataset provides important insights. For example, we show that each fund’s allocation to domestic equities largely follows the expected gradual decline over time, but the foreign equity allocation increases over time. Using this cross-section of TDF funds, we document significant differences in the performance of TDFs with the same target year. While some of the dispersion in performance may be due to sheer luck, it is conceivable that skill and other factors may play a role.

In our second contribution, by focusing on the asset allocations and fund expenses that deviate from the average within each vintage, we find that two of the main drivers of returns of TDFs across the same target date group are (i) the additional allocation to equities above the average for that target-year and (ii) if the expense ratio of the fund is lower than the average expense ratio of funds with the same target year. However, the outperformance seems beyond that attributable to lower costs or the strong performance of equities during our sample period. On a risk-adjusted return basis, these findings appear stronger for funds that are closer to their target year. An interesting finding is that there is a negative correlation between the deviation from the average allocation to equities and the expense ratio. This potential trade-off between risk and costs may indicate that fund managers seek to boost performance by increasing their equity exposure in low-cost funds. This may also be part of a strategy to chase ratings. Chang et al. (2021) find that among TDFs, Morningstar assigns significantly higher ratings to those with lower fees.Footnote 5 We also investigate the economic significance of these results through a bootstrap simulation, which reveals substantial differences in cumulative wealth based on investing in TDFs with high vs. low expense ratios, as well as low vs. high equity allocation. Our third contribution is to provide evidence of significant persistence in the risk-adjusted returns of funds in all target year groups over a three-year horizon. However, consistent with the well-documented phenomenon in the mutual fund literature, this persistence dissipates significantly over a five-year horizon.

Taken together, our findings have important implications for investors who default into these funds and are not aware of the potential for significant differences in the risk-taking and performance of funds within the same vintage. Plan sponsors need to gain a better understanding of the TDF construction methodology and equity exposure, as they seek to go beyond short-term performance metrics when evaluating a fund and think about matching the risk preferences of the plan participants. Our results should also be of interest to regulators who have already started to look into the administration of these funds.

Related literature

One strand of the TDF literature focuses on fund returns and factors affecting fund performance, such as the selection of assets to be included in the fund and agency issues. When looking at returns of 401K plans, Mitchell & Utkus (2022) show that the inclusion of TDFs as default investments in automatic enrollment plans improves the 401K returns and reduces idiosyncratic risk. Using Vanguard funds (exclusively indexed portfolios), Mitchell & Utkus (2022) show that low-cost target date series can raise retirement wealth by 50 percent compared to non-target date investors due to more efficient portfolio choice. Using an earlier dataset from Morningstar (covering the 2004-2012 period), Elton et al. (2015) study the asset allocation and performance of TDFs. They find that additional allocation of the TDFs structured as funds of funds are mostly offset by the low-cost funds they choose. Elton et al. (2015) document that the average alpha of the TDFs is negative over the sample period, but similar to funds found in mutual fund studies.

In exploring the relative performance of TDFs, multiple studies find some downsides to investing in TDFs. A paper that investigates the effect of different factors on TDF performance is Sandhya (2011) who shows that agency problems, due to the absence of flow-performance relation in TDFs, result in TDFs underperforming balanced funds. Building on the general findings that there exist conflicts in mutual fund families (Bhattacharya et al.; 2013), Sandhya (2011) provides evidence that fund managers are sometimes incentivized to use TDFs that are structured as funds of funds, as a means of holding on to funds that are either performing poorly or have high fees.

Another study that investigates the differences in realized returns of target date funds is by Balduzzi & Reuter (2019). They find that funds with the same target year expose investors to significantly different levels of realized returns and idiosyncratic risk. Balduzzi & Reuter’s (2019) results show that some of the dispersion in realized returns is due to risk-taking behavior of fund families striving to increase their market share. Risk matching due to targeting different clienteles is not significant in explaining the return and allocation heterogeneity among funds with the same target retirement year. Within a different framework, Johnson & Yi (2017) use Sharpe and Treynor ratios to explore the performance of target date funds relative to a balanced fund. Their analysis is specific to funds with target years 2035–2050 and they find that TDFs do not outperform naïve strategies. They show that fund’s alpha, assets under management, dividend yield and turnover are positively related to TDF’s better performance relative to a balanced fund. However, they do not find a relation between fund performance and expense ratio.

Another strand of the TDF literature explores the fund asset allocation strategies and questions whether the TDF glidepath is the optimal retirement investment strategy. Basu et al. (2011) compare wealth outcomes of different asset allocation approaches and show that deterministic approaches underperform dynamic allocation strategies. The dynamic asset allocation entails altering asset weights based on cumulative performance relative to investor’s target at that particular time. Basu et al. (2011) show that their proposed dynamic strategy produces higher terminal wealth than lifecycle strategies in about 80 percent of the scenarios. In a similar vein, Arnott et al. (2013) recommend more tactical approaches to the traditional glide-path strategy that would avoid one of the most common current pitfalls of TDFs, that of mechanistically switching into bonds, even when bonds are offering record-low yields. Within a different framework, Forsyth, Vetzal and Westmacott (2017) compare the performance of TDFs (following a glidepath asset allocation depending on time remaining to retirement) to the performance of a portfolio with constant asset allocation. They show that TDFs produce almost the same wealth outcome as constant proportion rebalancing and do not serve investors well. They propose an adaptive terminal wealth strategy in which each plan participant has their own personalized asset allocation strategy and the proportion invested in equities depends on the achieved wealth compared to the target.

As TDFs are structured as funds of funds, Brown & Davies (2020) study TDFs multiple layers of fees and show that TDF sponsors do not always choose the most cost-efficient funds to include in the fund. Using 50 low-fee Vanguard ETFs, the authors form replicating portfolios and show that TDFs can be outperformed by the proposed replicating low-cost portfolios. The main source of the better performance of the replicating portfolios is the lower fees, and to some extent the cash holdings of TDFs. Focusing on the relationship between TDF expenses and Morningstar ratings, Chang et al. (2021) show that lower cost funds are associated with higher Morningstar Analyst ratings and Quantitative ratings. More recently, Shoven & Walton (2021) investigate the performance of TDFs relative to a passive benchmark with the same asset allocation. They show that the distribution of TDFs expense ratios is bimodal, where low cost TDFs are mostly index funds, while high cost TDFs are actively managed. In terms of performance, the low-cost funds do as well as the benchmarks, while TDFs with higher fees generally underperform. The authors also study the relation between fund returns in the 2010–14 period and fund returns in the 2015–19 period. Their results point to a weak positive association between returns in the two time periods, i.e., past fund performance is not a strong predictor of future performance. Along these lines, using a very limited sample of surviving TDF series from 2009 to 2019, Mao & Wang (2022) study the evolution of the TDFs glidepath and notice equity risk reduction over that period. They suggest that this has led to better performance of the 2020 vintage TDFs during the 2020 COVID market meltdown compared to the 2010 TDFs performance during the 2008 crisis.

Building on these earlier findings, our main goal in this paper is to show how within the same vintage, differences in the expense ratio and variation in asset allocations contribute to cross-sectional differences in fund performance both on a real- and risk-adjusted basis. Our study differs from the framework of Brown & Davies (2020), who mostly focus on the comparison of TDFs against a replicating portfolio consisting of ETFs and from the analysis of Shoven & Walton (2021), who perform style analysis of TDFs and balanced funds, in addition to analyzing the impact of expense ratios on returns. Our analysis is also different from the approach of Balduzzi & Reuter (2019), who study the heterogeneity of the TDFs idiosyncratic risk and test whether it is linked to strategic risk taking (of fund managers) or risk matching (of employee profiles). Furthermore, we use a proprietary dataset from Morningstar, which provides a comprehensive cross-section of TDFs and includes the most granular asset allocations.

Sample construction, variable definitions, and descriptive statistics

We obtain the TDF data from Morningstar Inc. under a licensing agreement. The Morningstar database has the broadest coverage of open-ended mutual funds and is free of survivorship bias. Patel & Sarkissian (2017) compare mutual fund data from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) or Morningstar Principia (MP) to data from Morningstar Direct and demonstrate that it is substantially more accurate than both CRSP and MP, particularly in fund manager characteristics, and show the choice of database has implications when measuring fund performance.

Our sample includes the full sample of target date funds with retirement target year ranging from 2025 to 2050. Target date funds offer multiple share classes.Footnote 6 For each TDF share class within our sample, we collect the monthly (net) returns, monthly asset allocation, monthly net asset value (NAV), and the annual expense ratio. Morningstar provides returns that include both income and capital gains or losses and assumes that all income and capital gains distributions are reinvested. The returns are based on NAV that is net of management, administrative, 12b-1 fees and other costs. We aggregate the returns, asset allocations and expense ratios to the fund level by calculating weighted averages, using the NAVs as the weights. Our time series data is from 2007 to 2019 for target years 2025, 2030, 2035, 2040, 2045 and 2050.

Table 1 presents summary statistics of the annualized monthly returns by target year, for each year in our sample. To conserve space, we present the results for pairs of target years together. The distribution of the number of funds per year is very similar across each Panel. For example, Table 1 Panel A shows that the number of funds with target years 2025 and 2030 is a low of 41 in 2007 and gradually increases to 116 in 2018 and 2019. Similarly, Table 1 Panel B shows that the number of funds with target years 2035 and 2040 increases from a low of 39 in 2007 to its peak of 115 in 2018 and 2019, with the increase each year being similar to the trend in Panel A. The increase in number of funds in Table 1 Panel C for target years 2045 and 2050 is similar to Panels A and B. Together the trends in the number of funds suggest that while there is some variability in when new funds for each target year are introduced, within a few years of the first fund being introduced, the number of funds available usually reaches a steady state of approximately 115 funds per target year.

Table 1 shows some similarities in the average returns across target years. For example, during 2008, 2011, 2015, and 2018, the mean annualized fund return was negative for all target years. Furthermore, funds in all target years had their worst performance in 2008, the heart of the financial crisis; with the average annualized returns ranging from -34.2% for target years 2025 and 2030, to -37.8% for target years 2045 and 2050. As expected, during this period, funds intended for individuals with a longer time to retirement, fared worse as these funds would on average have greater exposure to market fluctuations. Similarly, 2009 was the best year for TDFs in our sample, with average annualized returns ranging from 28.3% for target year 2025 and 2030 to 31.5% for 2045 and 2050.

Notwithstanding the intertemporal similarities in the return patterns across funds, Table 1 shows the significant variability in the returns across funds within the same target year groups. For example, Panel A of Table 1 shows that in 2007, funds with target years 2025-2030 had a mean return of 6.9%. However, the first and third quartiles were 5.6% and 8.9%, respectively, for an interquartile range (IQR) of 3.3%. In fact, for these two vintages, throughout the sample period, the IQR averaged just under 3%, peaking at 5.2% in 2013. The other Panels of Table 1 show similar values for the IQRs of the returns for the other target year groups, with the average IQR for all target year groups greater than 2%.

Table 2 summarizes the annual mean percent allocation of the TDFs in our sample to Total Equity, Foreign Equity, Total Bond, Foreign Bond, Cash and Other. Similar to Table 1, we provide results for each year and by pairs of target years. As expected, within each target year, as the time to retirement approaches the allocation to Total Equity (Total Bond) decreases (increases). In 2007, TDFs with target years 2025 and 2030 had an average of 80.4% in equities and 13.5% in bonds; and in 2019, these amounts were 57.7% in equities and 38.4% in bonds. Furthermore, within each year, for target years that are further away, the equity share is larger, and the bond share is smaller. However, a close inspection of each Panel within Table 2 reveals some unexpected patterns. For example, the results for target years 2025 and 2030 in Panel A of Table 2 show that the equity allocation declines by a total of just under 2% per year on average, but the decline was not gradual. In fact, the larger annual changes (over 4%) mostly occur in the earlier years, with the smaller changes occurring in the latter years; there was even an increase in the equity share one year.

The results for the other target years in Panels B-C are even more striking, with the equity share increasing for five of the years in each panel, and the annual average decline in equity allocation being less than 1% for all target years between 2035 and 2050. However, there is significant deviations from the averages, especially for the funds that are relatively close to their target year during the financial crisis and immediately afterward.

Table 2 also shows that the allocation to foreign equity and foreign bond increased for most of the target years over the sample period. The only exception is the average foreign equity share in target years 2025 and 2030 which slightly decreased from approximately 23% in 2007 to 20% in 2019. The results for Cash and Other in Table 2 show that while each of these allocations tend to be less than 5% on average, they each have some of the highest variability across funds within the same target year. For all vintages, the allocation to Cash decreases over the sample period.

In Table 3 we summarize the total Assets Under Management (AUM) and the Expense Ratio by target year pairs, for each year in our sample. The results for AUM in Panel A show that except for 2008, there has been an almost steady increase in the amount of assets in these funds. In 2007, TDFs with target years of 2025 and 2030 had an average AUM of approximately $1,203 million but by 2019, the average value of the assets in these two target years had tripled to $3,775 million. The increase is similar for the other target years with the average size of the 2045 and 2050 funds increasing from $303 million in 2007 to $2,002 million in 2019. However, there is significant heterogeneity in the size of TDFs for all target years over the sample period. For example, in 2019, TDFs with target years 2035 and 2040 had $3,095 million on average in assets.

Unlike the increase in the size of TDF funds over time, Panel B of Table 3 shows that the annual expense ratio for these funds has mostly stayed flat or decreased over time. In 2007, the earliest starting date of our sample, the average annual expense ratio was between 29 bp for the 2045 and 2050 target years, and 38 bp for the 2025 and 2030 funds. On the other hand, by 2019, the annual expense ratio for the 2045-2050 funds was still about 29 bp while that for the 2025 and 2030 target years had fallen to 28 bp. There is also substantial variation in the expense ratios for the same year for each vintage. For example, the standard deviation of the expense ratio for the 2025-2030 funds was 0.36% in 2007, but decreased to 0.25% in 2019.

To estimate risk adjusted returns in the empirical models in the next section, we obtain monthly data on a value-weighted index of US stocks as a proxy for the US equity market, and the monthly risk-free rate from Kenneth French’s website. As proxies for the global equity markets and the bond markets, we obtain data on the MSCI world index (excluding the US), the Barclay’s US aggregate bond index and the Barclay’s global aggregate (excluding US) bond index, from Bloomberg.

Empirical models and results

Allocation deviations and fund performance

We start our empirical investigation by studying how deviations from the average asset allocations affect fund returns. We estimate variations of the following panel regression model for each target year:

The dependent variable WFReturni,t is the weighted return on fund i in month t. Equity_devi,t-1 is the deviation of the equity allocation of fund i from the mean total equity allocation across all funds in the same vintage as fund i during month t-1. In a similar vein, FEquity_devi,t-1, Bond_devi,t-1, FBond_devi,t are fund i’s foreign equity, total bond, and foreign bond deviations from the respective average allocations within each vintage. ln_AUMi,t is the natural logarithm of fund i’s weighted net asset value and ExpRatio_devi.t is the deviation of fund i’s expense ratio from the average expense ratio of the funds of the same vintage in month t. We include month dummies δt to control for time varying fixed effects across funds.

Table 4 presents results of three specifications of the model in (1) separately for each target year in our sample. In all specifications we include ln_AUMi,t and ExpRatio_devi.t . In column (i), we include only the deviation from the total equity allocation, in column (ii), we include only the deviation from the total bond allocation, and in column (iii), we include the deviations from the allocations to foreign equity and to foreign bond. Table 4 shows that, funds that have expense ratios that are lower than the average expense ratio of similar funds within any month, realize significantly higher returns in the following month. This finding is intuitively appealing as it suggests that when fund managers shift to lower cost funds, this effort is rewarded with higher return in the following month.

Table 4 also shows that positive deviations from the average total equity allocation lead to significantly higher fund returns in the following month. Conversely, higher than average allocations to bonds mostly lead to lower returns, but the effect is not as consistent as that observed for the total equity deviations. In the case of deviations from the average allocation to foreign equity and foreign bonds, these only affect subsequent returns for the shortest target years, i.e., for the 2025 vintage. Specifically, higher than average allocations to foreign equity (foreign bond) lead to significantly larger (smaller) returns in the subsequent month. We find no significant relation between the fund size and the fund returns in our sample period.

Expense ratio and equity deviations and fund alphas

We also explore whether deviations from the average expense ratio and equity allocation impact TDF returns on a risk-adjusted basis. This analysis would capture fund performance that is beyond that due solely to market fluctuations and would therefore address potential concerns that our finding is largely due to the strong performance of equities during our ample period.Footnote 7 We first estimate the fund alphas using 10 years of data (from 2010 to 2019) in a four-factor model, where the factors are the excess return on the CRSP value-weighted index, the MSCI world index (excluding the US), the Barclay’s US aggregate bond index and the Barclay’s global aggregate (excluding US) bond index. We then regress the alpha of each fund on its average expense ratio deviation and equity deviation over the period, using the following model:

αi,t is the alpha on fund i, Equity_devi, is the deviation of the equity allocation of fund i from the mean total equity allocation across all funds in the same vintage as fund i, and ExpRatio_devi is the deviation of fund i’s expense ratio from the average expense ratio of the funds of the same vintage.

The results for model (2) in Table 5 confirm that except for funds that have the longest time to retirement, positive deviations from the average total equity allocation are associated with significantly higher fund alphas. The relation with the expense ratio is, not surprisingly, negative. The results differ by target year of the fund, again nearby vintages are negative and significant (2025, 2030, 2040), while TDFs with longer time to retirement are either insignificant or marginally significant.Footnote 8

Persistence in performance

We next estimate the level of persistence in the risk-adjusted performance of TDFs. Following Grinblatt &Titman (1992), we first split the most recent 10 years of our sample period into two 5-year sub-periods, i.e., 2010–2014 and 2015–2019. We then use a four-factor model to estimate the fund alphas for each of the sub-periods separately for each TDF target year. Finally, we estimate a cross-sectional model of the alpha from the second sub-period (αPOST) on the alpha from the first sub-period (αPRE) per vintage.

If fund alphas are persistent, we expect a positive and significant coefficient estimate on β1. Table 6 presents results of the model in (2) for each vintage that we have adequate data for the pre- and post-sample periods. The results in the first row of Table 6 show that, there is only significant evidence of persistence for the medium to longer-term target years. In particular, we obtain highly significant persistence in the alphas for target year 2050 and marginal significance for target years 2040 and 2045. However, for the three shorter maturity vintages there is no significant relation between the alphas from each sub-period. These results are somewhat different from the five-year persistence results of Shoven & Walton (2021) who find a weak positive association between past and future five-year performance of TDFs. Part of this difference could be attributed to difference in the empirical modeling, i.e., while we estimate our regression models per target year, Shoven &Walton (2021) combine all TDF vintages in one model.Footnote 9

As some mutual funds studies show (such as Elton, Gruber and Blake 1996), the persistence of excess returns of mutual funds is documented to be stronger over shorter time horizons such as three years. We test whether this applies to our sample of target date funds in the second panel of Table 6. The results indicate that persistence in TDF alphas is much stronger over three-year horizons, where the slope of the regression of past three-year alpha on future three-year alpha is highly significant for all target years, with the exception of the 2030 vintage where it is significant at 10%.

Bootstrap simulation of performance

Our regression results in Section "Empirical models and results" provide evidence of significant differences in the monthly returns of funds based on their deviations from the average expense ratios and deviations from the average equity allocations of funds of the same vintage. In particular, funds that have expense ratios that are higher than the average expense ratios of funds with the same target year, earn significantly lower returns; and funds with higher equity allocations than the average equity allocations of funds in that vintage, earn significantly higher returns. While these results are significant of themselves, the natural question is whether the return differences we observe are economically significant. In other words, would these deviations from the average allocations have a meaningful impact on the retirement savings of an average investor. Target date funds are most attractive to investors who want the convenience of not having to continually adjust their retirement savings themselves overtime. Therefore, we investigate the long-term impact on the investor’s retirement savings of choosing a fund with a higher-than-average expense ratio or equity allocation.

Ideally, we would like to test the average fund performance over a longer time period than the 10-years of data that we have. To address this data limitation, we conduct a bootstrap-styled simulation, similar to Dichtl & Drobetz (2015). We describe the methodology for the expense ratio analysis. First, we group the funds for each vintage based on their expense ratio. Funds with expense ratios that are higher than the average expense ratio for that vintage are referred to as the high-expense ratio funds and those with expense ratios that are lower than the average are labeled the low-expense ratio funds. Next, we calculate the average monthly returns for each of these two groups within each vintage. For example, for the 2030 fund, we have a time-series of 120 monthly returns for each of the two groups from January 2010 to December 2019. We then divide each of the monthly returns within each group according to the particular month, i.e., 10 returns for January, February, etc. Next, we simulate an additional 10 years of monthly data for each of the expense ratio groups within each target-year, by drawing with replacement 10 returns for each of the months between January 2020 and December 2029. We restrict each monthly draw for the simulated data to the corresponding months in the actual data. We repeat the process 10,000 times and calculate the average monthly returns for each of the 120 months based on the simulated data for each of the two expense ratio groups. Finally, we calculate the cumulative returns over the 20 year-period, i.e., actual plus simulated data, for each of the two expense ratio groups. We perform the same steps for high- versus low-equity deviation, by forming two sub-groups within each vintage based on the deviation from average equity allocation within that vintage.

Figure 1 plots the average cumulative returns of the 2030 funds over the 20 years. In Panel A, we report results for the sub-groups based on the funds’ deviation from average expense ratio and Panel B provides similar results based on the deviation from average equity allocation within that vintage. Figure 1 shows that over the 20-year period, low expense-ratio 2030 funds would earn an average cumulative return that is 119.90% higher than their high-expense ratio counterparts (453.82% vs. 333.92%). Similarly, the cumulative return on high equity allocation 2030 funds is 143.35% higher than the low-equity allocation funds (470.46% vs 327.11%). To translate these numbers into actual dollar amounts, consider a hypothetical single person, Sarah Jones, who is in her mid-forties at the end of 2009 and has $100,000 invested in a 2030 high-expense ratio fund. If Sarah does not make any further additions to (or withdrawals from) her account over the next 20 years, at the end of 2029, she would have an average savings of $433,922.59. In comparison, if Sarah invests in a low-expense ratio 2030 TDF, she will end up with an average balance of $553,822.62, a difference of $119,900.04. Similarly, if starting in January 2010, Sarah has $100,000 invested in a 2030 TDF with higher-than-average allocation to equities, over the 20-year period, her savings would grow to $570,462.22, compared to $427,111.84 if she invests in a 2030 fund with a lower-than average allocation to equities, a difference of $143,350.38.

Conclusions

We make three important contributions to the literature on TDF performance. First, by using a large cross-section of TDF funds, we document substantial differences in the performance, asset allocation and expense ratios of TDFs with the same target year, as well as different patterns of evolution of these variables over our sample period. While the average expense ratio has decreased over time, there are still large differences across funds within the same target year.

Second, we provide empirical evidence on the main drivers of returns of TDFs across the target date groups and show that the allocation to equities and the expense ratio play a significant role. We show that funds that have expense ratios that are lower than the average expense ratio of funds in the same target year group realize significantly higher returns subsequently, while higher allocation to equity results in higher subsequent returns. Whereas TDF allocation to foreign bonds and foreign equity has increased over the sample period, the deviations from the average allocation to foreign equity and foreign bonds only affect subsequent returns for the funds with nearest target years. When four factor fund alphas are considered, the strong relation of alphas with expense ratio and with allocation to equity above/below the average remains consistent. Our third contribution is to provide evidence on short- versus longer-term persistence in TDF alphas. Similar to the mutual fund industry findings, we show that the persistence of excess returns of target date funds is stronger over shorter time horizons such as three years.

On a broader scale, even though plan administrators provide information on fund performance to the plan participants, plan participants do not know much about the reasons for the TDF choices, and that funds having the same target retirement year may have very different asset allocation, risk exposure, structure and fees. As more research findings similar to ours surface, lawsuits against plan administrators are increasingFootnote 10, including allegations that they have breached their fiduciary duties by failing to select carefully the plan's investment options from all target date funds available. Our research results have implications for both individual investors and retirement plan administrators looking to identify and monitor some of the drivers of the TDFs performance. Due to the lack of uniformity in the TDF glide path and expenses, plan sponsors should offer multiple options to plan participants, compare against prudent alternatives and use bargaining power to select share classes with lower expenses. Practitioners in the mutual fund industry concur with these sentiments.

Notes

Letter to the Government Accountability Office (GAO) from the chairs of the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, and the House Education and Labor Committee requesting that it conducts a review of TDFs (https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/050621%20GAO%20Target%20Date%20Fund%20Request%20FINAL.pdf)

See for example, Ramsey, A. (2022). BlackRock 401(k) Suits Pressure Labor Department to Act.

There may be other potential explanations for the negative correlation we observe between the deviation from average allocation to equities and the expense ratio. For example, Sandhya (2011) argues that there may be different cost structure depending on whether the TDF is invested in a family fund.

The starting sample that we received from Morningstar includes 4,739 TDF share classes. We dropped share classes that had missing allocations, returns and other data used in our analysis, during our sample period.

While the return on equities was positive for most years in our sample period, there were a few notable exceptions, including the financial crisis year of 2008.

We also calculate average gross and net returns per quartile of the expense ratio and find that the lowest expense ratio quartile has larger returns than the highest expense ratio quartile, both on gross and return net basis. For the highest expense ratio quartile, there is a sharp divide between the gross returns and the net returns, suggesting disproportionate impact of high expense ratio on fund performance. The results are available upon request. We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the need to investigate whether the performance loss is attributable solely to higher costs.

Shoven & Walton (2021) only use returns for the funds that have returns over the entire 10-year period which may introduce survivorship bias, while we require minimum of 12 observations in each 5-year period (i.e., at least 24 months).

References

Agnew, J.R. 2006. Do behavioral biases vary across individuals? Evidence from individual level 401 (k) data. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 41 (4): 939–962.

Arnott, R.D., K.F. Sherrerd, and L. Wu. 2013. The glidepath illusion… and potential solutions. The Journal of Retirement 1 (2): 13–28.

Balduzzi, P., and J. Reuter. 2019. Heterogeneity in Target Date Funds: Strategic Risk-taking or Risk Matching?. The Review of Financial Studies 32 (1): 300–337.

Basu, A.K., A. Byrne, and M.E. Drew. 2011. Dynamic lifecycle strategies for target date retirement funds. The Journal of Portfolio Management 37 (2): 83–96.

Benartzi, S., and R.H. Thaler. 2007. Heuristics and biases in retirement savings behavior. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (3): 81–104.

Bhattacharya, U., J.H. Lee, and V.K. Pool. 2013. Conflicting family values in mutual fund families. The Journal of Finance 68 (1): 173–200.

Brown, D.C. and Davies, S., 2020. Off Target: On the Underperformance of Target-Date Funds. Available at SSRN.

Chang, C.E., T.M. Krueger, and H.D. Witte. 2021. Importance of costs in target date fund selection using three Morningstar ratings. The Journal of Retirement 8 (4): 66–83.

Dichtl, H., and W. Drobetz. 2015. Sell in May and go away: still good advice for investors?. International Review of Financial Analysis 38: 29–43.

Elton, E.J., M.J. Gruber, and C.R. Blake. 1996. The persistence of risk-adjusted mutual fund performance. Journal of Business 69: 133–157.

Elton, E.J., M.J. Gruber, A. De Souza, and C.R. Blake. 2015. Target date funds: Characteristics and performance. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies 5 (2): 254–272.

Forsyth, P., Vetzal, K.R. and Westmacott, G., 2017. Target Wealth: The Evolution of Target Date Funds. Available at SSRN 2980952.

Grinblatt, M., and S. Titman. 1992. The persistence of mutual fund performance. The Journal of Finance 47 (5): 1977–1984.

Huberman, G., and W. Jiang. 2006. Offering versus choice in 401 (k) plans: Equity exposure and number of funds. The Journal of Finance 61 (2): 763–801.

Johnson, W.F., and H.C. Yi. 2017. Do target date mutual funds meet their targets?. Journal of Asset Management 18: 566–579.

Mao, M.Q., and C.H. Wong. 2022. Why have target-date funds performed better in the COVID-19 selloff than the 2008 selloff?. Journal of Banking & Finance 135: 106367.

Mitchell, O.S., and S.P. Utkus. 2022. Target-date funds and portfolio choice in 401 (k) plans. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 21 (4): 519–536.

Patel, S., and S. Sarkissian. 2017. To group or not to group? Evidence from mutual fund databases. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52 (5): 1989–2021.

Sandhya, V., 2011. Agency problems in target-date funds. Working Paper.

Shoven, J.B., and D.B. Walton. 2021. An analysis of the performance of target date funds. The Journal of Retirement 8 (4): 43–65.

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium. This project is funded by the Faculty Research and Support Funds at the University of Houston – Clear Lake and by the John Chambers College of Business and Economics at West Virginia University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pavlova, I., Hibbert, A.M. Performance dispersion among target date funds. J Asset Manag 25, 369–382 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-024-00349-0

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-024-00349-0