Abstract

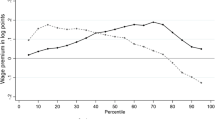

This paper examines differences in the wage-offer functions between males and females in the insurance industry. The results of random forest regression (RFR) residual analysis and quantile regressions (QRs) by gender indicate considerable inequities for underwriters, sales agents, and claims adjusters. We find relatively modest wage inequities among actuaries. Underwriters’ and adjusters’ gender wage inequality lies between the actuaries and sales agents. Across the specifications (RFR, QR, and the OLS benchmark), males benefit more from experience than females except for actuaries. In addition, males generally have a greater return to education than females (except for actuaries). Sales agents’ jobs exhibit the greatest inequality, with extremely high values for the regression Gini index of inequality at the upper quantiles. Actuaries exhibit the least amount of gender inequality across the board, with demographic responses suggesting competitive pressures across states yielding the least wage-offer inequality across gender. In summary, taste-based discrimination, social employment networks, difficulties in assessing productivity in heterogeneous work situations, competitiveness in the labor market, and the flexibility of work hours help explain our findings for different occupations in the insurance industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use quantile regressions because they can address both linear and nonlinear wage-offer functions.

Gowri (2004) suggests that underwriters intend to rate risks even though they may not intend to deprive high risk persons of insurance.

The results of the first stage RFRR machine learning models are available upon request.

All the residual values are from random forest residual regressions.

SAS programs for the calculation of the regression Gini indices, and the random forest two-stage residual regressions, are available upon request.

Labor market impediments—as we define the term here as anything that drives a wedge between workers’ wages and the value of their marginal product—generally includes monopsony, trade unions, difficult to measure productivity, geographical immobilities, occupational immobilities, and poor information. Our framework does not discuss monopsony and trade unions because the insurance labor market is competitive and has no trade union. Our empirical models partially control for geographical immobilities.

Female claim adjusters may also suffer from consumers’ taste-based discrimination because consumers need to interact with adjusters for claims.

This argument is based on our conversation with a professor who worked for an insurance company and a former executive in an insurance company. We are not able to find any statistics to support this argument. It is anecdotal evidence.

The Young Producer Study was conducted by Regan Consulting and sponsored by The Council of Insurance Agents and Brokers. The study is to access the hiring activity and identify the firms that have successful hiring young produces in the insurance industry.

If female agents and male agents have equal chance to sell insurance products, both commercial lines and personal lines, then gender inequity is not likely to persist in the long run as female referral conduits are generated, and as profit-maximizing owners seek to maximize profits by employing equally productive but lower cost alternatives to sale insurance.

There are either union-enforced or social-norm-enforced restrictions on variability in pay in the school-teacher space.

Wages of sale agents include commissions and bonuses paid by their employer in our empirical data.

See Blau and Kahn (2017, p. 791).

References

Arrow, K.J. 1972. Some mathematical models of race in the labor market. In Racial discrimination in economic life, ed. Anthony Pascal, 187–203. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Arulampalam, W., A.L. Booth, and M.L. Bryan. 2007. Is there a glass ceiling over Europe? Exploring the gender pay gap across the wage distribution. ILR Review 60 (2): 163–186.

Beaman, L., N. Keleher, and J. Magruder. 2018. Do job networks disadvantage women? Evidence from a recruitment experiment in Malawi. Journal of Labor Economics 36 (1): 121–157.

Becker, G.S. 1957 (revised, 1971). The economics of discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bedi, A.S., and J.H. Edwards. 2002. The impact of school quality on earnings and educational returns—Evidence from a low-income country. Journal of Development Economics 68 (1): 157–185.

Blau, F., and L.M. Kahn. 2017. The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature 55 (3): 789–865.

Bronson, C. 2014. Gender-based pricing warrants new long-term care marketing. Insurance Business America.

Brown, C., and M. Corcoran. 1997. Gender-based differences in school content and the male–female wage gap. Journal of Labor Economics 15 (3): 431–465.

Budd, J.W., and B.P. McCall. 2001. The grocery stores wage distribution: A semi-parametric analysis of the role of retailing and labor market institutions. ILR Review 54 (2A): 484–501.

Butler, Richard J., William G. Johnson, and Barbara Wilson. 2012. A modified measure of health care disparities applied to birth weight disparities and subsequent mortality. Health Economics 21 (2): 113–126.

Butler, Richard J., and James B. McDonald. 1987. Interdistributional income inequality. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 5 (1): 13–18.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2011. Spotlight on women. https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2011/women/.

Burks, S.V., B. Cowgill, M. Hoffman, and M. Housman. 2015. The value of hiring through employee referrals. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 130 (2): 805–839.

Card, D., T. Lemieux, and W.C. Riddell. 2020. Unions and wage inequality: The roles of gender, skill and public sector employment. Canadian Journal of Economics/revue Canadienne D’économique 53 (1): 140–173.

Castilla, E.J. 2005. Social networks and employee performance in a call center. American Journal of Sociology 110 (5): 1243–1283.

Castagnetti, C., and M.L. Giorgetti. 2019. Understanding the gender wage-gap differential between the public and private sectors in Italy: A quantile approach. Economic Modelling 78: 240–261.

Charles, K.K., and J. Guryan. 2008. Prejudice and wages: An empirical assessment of Becker’s The Economics of Discrimination. Journal of Political Economy 116 (5): 773–809.

Chay, K.Y., and B.E. Honore. 1998. Estimation of semiparametric censored regression models: An application to changes in black–white earnings inequality during the 1960s. Journal of Human Resources 33 (1): 4–38.

Chernozhukov, V., D. Chetverikov, M. Demirer, E. Duflo, C. Hansen, W. Newey, and J. Robins. 2018. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. The Econometrics Journal 21 (1): C1–C68.

Costanzo, A., and M. Desimoni. 2017. Beyond the mean estimate: A quantile regression analysis of inequalities in educational outcomes using INVALSI survey data. Large-Scale Assessments in Education 5 (1): 14.

Eide, E.R., and M.H. Showalter. 1999. Factors affecting the transmission of earnings across generations: A quantile regression approach. Journal of Human Resources 34 (2): 253–267.

Eide, E.R., M.H. Showalter, and D.P. Sims. 2002. The effects of secondary school quality on the distribution of earnings. Contemporary Economic Policy 20 (2): 160–170.

Etienne, J.M., and M. Narcy. 2010. Gender wage differentials in the French nonprofit and for-profit sectors: Evidence from quantile regression. Annals of Economics and Statistics 99 (100): 67–90.

Fan, C.S., X. Wei, and J. Zhang. 2017. Soft skills, hard skills, and the black/white wage gap. Economic Inquiry 55 (2): 1032–1053.

Fortin, N.M., and T. Lemieux. 1998. Rank regressions, wage distributions, and the gender gap. Journal of Human Resources 33 (3): 610–643.

Frisch, R., and F.V. Waugh. 1933. Partial time regressions as compared with individual trends. Econometrica 1: 387–401.

Gardeazabal, J., and A. Ugidos. 2005. Gender wage discrimination at quantiles. Journal of Population Economics 18 (1): 165–179.

Gowri, A. 2004. When responsibility can’t do it. Journal of Business Ethics 54: 33–50.

Hillman, A.J., C. Shropshire, and A.A. Cannella Jr. 2007. Organizational predictors of women on corporate boards. Academy of Management Journal 50 (4): 941–952.

Huddy, L., and N. Terkildsen. 1993. Gender stereotypes and perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science 37 (1): 119–147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111526.

Ioannides, Yannis M., and Linda Datcher Loury. 2004. Job information networks, neighborhood effects, and inequality. Journal of Economic Literature 42 (4): 1056–1093.

Kunreuther, H. 1989. The role of actuaries and underwriters in insuring ambiguous risk. Risk Analysis 9 (3): 319–328.

Lang, Kevin, and Jee-yeon Lehmann. 2012. Racial discrimination in the labor market: Theory and empirics. Journal of Economic Literature 50 (4): 1–48.

Lemieux, T. 2006. Postsecondary education and increasing wage inequality. American Economic Review 96 (2): 195–199.

Leuze, K., and S. Strauß. 2016. Why do occupations dominated by women pay less? How ‘female-typical’ work tasks and working-time arrangements affect the gender wage gap among higher education graduates. Work, Employment and Society 30 (5): 802–820.

Lovell, M.C. 1961. Seasonal adjustment of economic time series. Journal of the American Statistical Association 58: 993–1010.

McGuinness, S., and J. Bennett. 2007. Overeducation in the graduate labour market: A quantile regression approach. Economics of Education Review 26 (5): 521–531.

Melly, B. 2005. Public–private sector wage differentials in Germany: Evidence from quantile regression. Empirical Economics 30 (2): 505–520.

Miller, P.W. 2009. The gender pay gap in the US: Does sector make a difference? Journal of Labor Research 30 (1): 52–74.

Muench, U., J. Sindelar, S.H. Busch, and P.I. Buerhaus. 2015. Salary differences between male and female registered nurses in the United States. JAMA 313 (12): 1265–1267.

Muench, U., and H. Dietrich. 2019. The male–female earnings gap for nurses in Germany: A pooled cross-sectional study of the years 2006 and 2012. International Journal of Nursing Studies 89: 125–131.

Parness, J.A. 2003. Civil claim settlement talks involving third parties and insurance company adjusters: When should lawyer conduct standards apply? John’s Law Rev. 77: 603.

Prendergast, G.P., S.S. Li, and C. Li. 2014. Consumer perceptions of salesperson gender and credibility: An evolutionary explanation. Journal of Consumer Marketing 31 (3): 12.

Oaxaca, R. 1973. Male–female differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review 14: 693–709.

O’Neill, J. 1985. The trend in the male–female wage gap in the United States. Journal of Labor Economics 3 (1, Part 2): S91–S116.

Ruggles, S., S. Flood, R. Goeken, J. Grover, E. Meyer, J. Pacas, and M. Sobek. 2020. IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 (dataset). Minneapolis: IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V10.0.

Stanton, C.T., and C. Thomas. 2016. Landing the first job: The value of intermediaries in online hiring. The Review of Economic Studies 83 (2): 810–854.

Stigler, G.J. 1962. Information in the labor market. Journal of Political Economy 70 (5, Part 2): 94–105.

Reagan Consulting. 2019. Young Producer Study. Reagan Consulting. TSM. Fall.2020.pdf

Turner, J.H. 2008. An analysis of factors affecting life insurance agent sales performance. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 12 (1): 71–79.

Verropoulou, G., and C. Tsimbos. 2013. Modelling the effects of maternal socio-demographic characteristics on the preterm and term birth weight distributions in Greece using quantile regression. Journal of Biosocial Science 45 (3): 375–390.

Wellington, A.J. 1993. Changes in the male/female wage gap, 1976–85. Journal of Human Resources 28 (2): 383–411.

Wilson, B.L., M.J. Butler, R.J. Butler, and W.G. Johnson. 2018. Nursing gender pay differentials in the new millennium. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 50 (1): 102–108.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest. The only support for this research was academic computational support.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 12 , 13 , 14 and 15 .

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Butler, R.J., Lai, G. Insurance wage-offer disparities by gender: random forest regression and quantile regression evidence from the 2010–2018 American Community Surveys. Geneva Risk Insur Rev 48, 192–229 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s10713-022-00078-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s10713-022-00078-7