Abstract

Although several studies have shown that inward foreign direct investment (FDI) often leads to greater host country productivity, researchers have yet to determine the relative importance of direct technology transfer and competitive pressure. To assess the relative importance of the two channels, we examine the US auto-component industry between 1979 and 1991. During this period, Japanese automobile assemblers began to produce vehicles in North America, and began to purchase inputs from US auto-component manufacturers. Those US manufacturers that sold components to Japanese transplants would be the direct recipients of any technologies transferred from the Japanese. Although we find that the direct investment by Japanese assemblers was associated with overall productivity improvement in the US auto-component industry, we find little evidence of direct technology transfer. The productivity growth of US suppliers affiliated with Japanese assemblers was no greater than that of other, non-affiliated US suppliers. Further, we find that the Japanese assemblers tended to purchase components from less productive US suppliers and, moreover, that low-productivity suppliers that sold goods to Japanese assemblers had a higher survival rate than low-productivity suppliers that did not sell to Japanese firms. The results suggest that increased competitive pressure in the auto-sector was the main cause of overall productivity improvement, at least during the initial stages of FDI of the 1980s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A few other foreign-owned assembly facilities operated during the study period. Volkswagen opened a facility in Pennsylvania in 1974 but had low sales volumes from the start and closed it in 1988. In Canada, Volvo opened a small facility during the 1970s, and Hyundai established a plant at the end of the study period. We exclude the Volkswagen, Volvo and Hyundai investments in our study because of the facilities' small volumes and the difficulty in obtaining the necessary supplier information. Overall, we expect that they had little impact.

Another potential channel for direct technology transfer is a supplier-to-supplier channel between Japanese-owned suppliers and American-owned suppliers. About 150 Japanese auto component suppliers entered the USA during the 1980s and about 25 Japanese-owned suppliers entered the USA even earlier, during the 1960s and 1970s (Martin et al., 1995, 1998). Some of the Japanese suppliers formed joint ventures with US parts suppliers. However, all the US–Japanese supplier joint ventures sold goods to Japanese assembly transplants during the 1980s, so that the supplier-to-supplier channel also involves direct sales relationships between American-owned suppliers and Japanese-owned assembly transplants. Thus the presence of a tie-in supply relationship between a Japanese assembler and a US supplier provides a single indicator that denotes possible direct technology transfer from Japanese automobile manufacturers to American suppliers.

For a firm entering in 1988, we use the firm's 1988 input and output data to obtain residuals from the estimated 1979, 1980, and 1981 production functions. We take the average, and then subtract the average productivity growth between 1981 and 1988 for all non-late entrants that survived in the period. The result is PROD_RES0 for the firm.

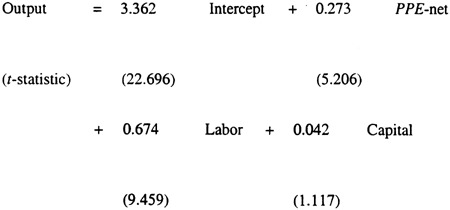

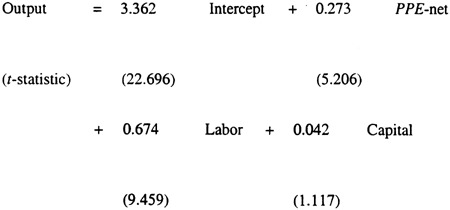

The estimated three-factor productivity function is (adjusted R 2=0.97):

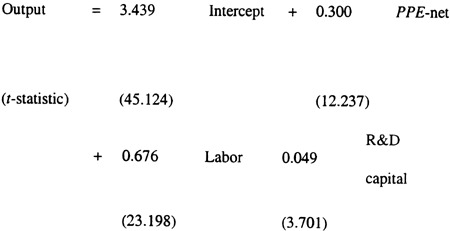

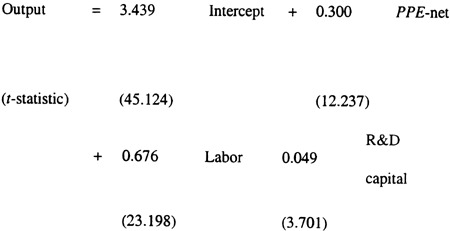

We construct a basic productivity measure similar to PROD_RES_AN. Instead of estimating three-factor production functions every year, we pool all firm-years and estimate a single function for the entire panel. A firm-year residual from this single function then represents how far a firm falls from the overall panel average in a given year. This measure allows us to ask how each firm responds across time on a yearly basis from an absolute reference. The estimated equation is (adjusted R 2=0.97):

Richard Caves drew our attention to the rent-extraction interpretation. Cusumano and Takeishi (1991) used a survey of two US assemblers, five Japanese transplant assemblers, and three Japanese-owned auto assembly facilities in Japan; they reported several findings pertinent to the possibility of rent extraction. First, Japanese transplants focused more on a supplier's capability to meet a buyer's target price in selecting component suppliers than US assemblers did. Second, US assemblers and Japanese transplants reported almost identical target-price ratios, which is the actual part price at market introduction divided by the target price the auto maker set when the part's major supplier was selected. Third, the transplants performed somewhat better than the US firms in obtaining price decreases from US suppliers (–0.6% vs an increase of 0.9%) (Cusumano and Takeishi, 1991, 573).

We measured capital earnings as net income after taxes with depreciation and interest expenses added back. We then scaled annual earnings by sales or total assets to measure yearly return on sales (ROS t ) and return on assets (ROA t ). We defined the change in return on sales in year t, DROS t , as the yearly difference between 2-year averages: (ROS t+1+ROS t+2)/2−(ROA t−1+ROA t−2)/2. (We use multiple year averages to reduce transitory shocks in capital return data. Our results are equivalent when we use 3-year averages, though the number of observations declines because there were insufficient data to obtain 3-year averages for some late tie-in firms.) We defined change in the rate of return on assets, DROA t , similarly. To determine whether tie-in relationships adversely affected change in capital earnings, we constructed an ‘abnormal change in capital earnings’ measure for tie-in firms. First, we obtained the average change in capital earnings for non-tie-in firms (average of DROS t and DROA t ) for each year t. Then we subtracted the average from the DROS t and DROA t of firms forming a tie-in relationship in year t. We call the differences ADROS t and ADROA t ‘abnormal change’ in the rate of return on sales and on assets among firms forming a tie-in relationship in year t. Third, we pooled ADROS t and ADROA t over all years t and all firms forming a tie-in relationship in year t. We tested whether the average values of ADROS and ADROA differ significantly from zero. If rent extraction occurs, then the coefficient on ADROS t and ADROA t will be negative, suggesting that tie-in firms' capital earnings would decrease after the firms formed tie-in relationships. Instead, we found that ADROS t and ADROA t were insignificantly positive (0.0136 with a t-statistic of 1.602 and 0.0064 with a t-statistic of 0.595).

References

Aitken, B.J. and Harrison, A.E. (1999) ‘Do domestic firms benefit from direct foreign investment? Evidence from Venezuela’, American Economic Review 89 (3): 605–618.

Blomström, M. (1986) ‘Foreign investment and productive efficiency: the case of Mexico’, Journal of Industrial Economics 35 (1): 97–110.

Blomström, M. and Persson, H. (1983) ‘Foreign investment and spillover efficiency in an underdeveloped economy: evidence from the Mexican manufacturing industry’, World Development 11 (6): 493–501.

Buckley, P. and Casson, M. (1976) The Future of the Multinational Enterprise, Holmes & Meier: New York.

Caves, R.E. (1974) ‘Multinational firms, competition, and productivity in host-country markets’, Economica 41: 176–193.

Caves, R. and Porter, M. (1976) ‘Barriers to Exit’, in R.T. Masson and P.D. Qualls Essays on Industrial Organization in Honor of Joe S. Bain, Ballinger: Cambridge, MA. pp 39–69.

Chung, W. and Alcacer, J. (2002) ‘Knowledge seeking and location choice of foreign direct investment in the United States’, Management Science 48 (12): 1534–1554.

Clark, K.B., Chew, B.W. and Fujimoto, T. (1987) ‘Product development in the world auto industry’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 3: 729–771.

Clark, K.B. and Fujimoto, T. (1991) Product Development Process, Free Press: New York.

Cusumano, M.A. and Takeishi, A. (1991) ‘Supplier relations and management: a survey of Japanese, Japanese-transplant, and US auto plants’, Strategic Management Journal 12: 563–588.

Cutler, D.M. and Katz, L.F. (1991) ‘Macroeconomic performance and the disadvantaged; comments and discussion’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 1–74.

Dunne, T., Roberts, M.J. and Samuelson, L. (1989) ‘The growth and failure of US manufacturing plants’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 104: 671–698.

ELM International (1989, 1991) ELM Guide to Automotive Sourcing, 2nd and 3rd edns), ELM International Inc.: Lansing, MI.

Evans, D.S. (1987) ‘Tests of alternative theories of firm growth’, Journal of Political Economy 95: 657–674.

Globerman, S. (1979) ‘Foreign direct investment and ‘spillover’ efficiency benefits in Canadian manufacturing industries’, Canadian Journal of Economics 12 (1): 42–56.

Griliches, Z. (1986) ‘Productivity, R&D, and basic research at the firm level in the 1970s’, American Economic Review 76 (1): 141–154.

Haddad, M. and Harrison, A. (1993) ‘Are there positive spillovers from direct foreign investment? Evidence from panel data for Morocco’, Journal of Development Economics 42: 51–74.

Hall, B. (1987) ‘The relationship between firm size and firm growth in the US manufacturing sector’, Journal of Industrial Economics 35 (4): 583–605.

Hall, B.H., Mansfield, E. and Jaffe, A.B. (1993) ‘Industrial research during the 1980s: did the rate of return fall? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Microeconomics 2: 289–343.

Helper, S. and McDuffie, J.P. (1997) ‘Creating lean suppliers: diffusing lean production through the supply chain’, California Management Review 39 (4): 118–151.

Kokko, A. (1994) ‘Technology, market characteristics, and spillovers’, Journal of Development Economics 43: 279–293.

Lieberman, M.B., Helper, S. and Demeester, L. (1999) ‘The empirical determinants of inventory levels in high-volume manufacturing’, Production and Operations Management 45 (4): 466–486.

Lieberman, M.B., Lau, L.J. and Williams, M.D. (1990) ‘Firm-level productivity and management influence: a comparison of US and Japanese automotive producers’, Management Science 36 (10): 1193–1215.

Martin, X., Mitchell, W. and Swaminathan, A. (1995) ‘Recreating and extending Japanese automobile buyer-supplier links in North America’, Strategic Management Journal 16: 580–619.

Martin, X., Mitchell, W. and Swaminathan, A. (1998) ‘Organizational evolution in an interorganizational environment: vertical, competitor, and community-level influences on supplier expansion to foreign markets’, Administrative Science Quarterly 43: 566–601.

Mitchell, W. (1994) ‘The dynamics of evolving markets: the effects of business sales and age on dissolutions and divestitures’, Administrative Science Quarterly 39 (4): 575–602.

Nickell, S.J. (1996) ‘Competition and corporate performance’, Journal of Political Economy 104 (4): 724–746.

Womack, J., Jones, D. and Roos, D. (1990) The Machine that Changed the World, MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Zaheer, S. and Mosakowski, E. (1997) ‘The dynamics of the liability of foreignness: a global study of survival in financial services’, Strategic Management Journal 18 (6): 439–463.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the helpful suggestions of James Bodurtha, Richard Caves, Gunter Dufey, Mark Huson, Doug Joines, Randall Morck, Rolf Mirus, Subi Rangan, J. Myles Shaver, Joel Slemrod and Bernie Wolf, as well as the editorial assistance of Nancy Kotzian. We are responsible for all errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Tom Brewer; outgoing Editor, August 2002.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, W., Mitchell, W. & Yeung, B. Foreign direct investment and host country productivity: the American automotive component industry in the 1980s. J Int Bus Stud 34, 199–218 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400017

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400017