Abstract

Since the Asian financial crisis of 1997–1998, the International Monetary Fund (the Fund) has been embroiled in an international crisis of legitimacy. Assertions of a crisis are premised on the notions that the Fund's voting system is unfair, that the Fund enforces homogeneous policies onto borrowing member states and that loan programmes tend to fail. Seen this way, poor institutional and policy design has led to a loss of legitimacy. But institutionalised inequalities or policy failure is not in itself sufficient to constitute an international crisis of legitimacy. This article provides a conceptually-driven discussion of the sources of the Fund's international crisis of legitimacy by investigating how its formal ‘foreground’ institutional relations with its member states have become strained, and how informal ‘background’ political and economic relationships are expanding in a way that the Fund will find difficult to re-legitimate. The difference between the Fund's claims to legitimacy and how its member states, especially borrowers, act has led to the creation of a ‘legitimacy gap’ that is difficult to close. However, identifying the sources of the Fund's international crisis of legitimacy allows us to explore what avenues are available to resolve the crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

3 Of course it is necessary to specify, case by case, when the failure to implement policy is not due to a lack of belief but due to technical or financial capacities. While in the past the Fund concentrated on building administrative, technical, and financial capacities, its recent shift to stressing ‘political will’ and ‘transparency’ in member states points to a legitimation problem rather than to a ‘know-how’ or resources problem.

4 As commented to me in an interview with a Fund staff member in Washington, DC, August 2005.

5 Interview with staff member of Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF, in Washington, DC, August 2005.

6 ‘IMF Board of Governors Approves Quota and Related Governance Reforms’, IMF Press Release No. 6/205, September 18, 2006, www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2006/pr06205.htm.

References

Ahluwalia, M.S. (2003) ‘IMF Operations and Democratic Governance: Some Issues’, public address to the General Assembly of the Club de Madrid, November 1, www.clubmadrid.org.

Babb, S. (2003) ‘The IMF in Sociological Perspective: A Tale of Organizational Slippage’, Studies in International Comparative Development 38 (2): 3–27.

Barnett, M. and Duvall, R. (2005) ‘Power in International Politics’, International Organization 59 (1): 39–75.

Barnett, M. and Finnemore, M. (2004) Rules for the World, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Best, J. (2005) The Limits of Transparency, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Best, J. (2006) ‘Civilizing through Transparency: The International Monetary Fund’, in B. Bowden and L. Seabrooke (eds.) Global Standards of Market Civilization, London: Routledge/RIPE Global Political Economy Series, 134–145.

Bienen, H.S. and Gersovitz, M. (1985) ‘Economic Stabilization, Conditionality, and Political Stability’, International Organization 39 (4): 729–754.

Bird, G. (2001) ‘A Suitable Case for Treatment? Understanding the Ongoing Debate about the IMF’, Third World Quarterly 22 (5): 823–848.

Bird, G. (2003) The IMF and the Future, London: Routledge.

Bordo, M.D. and James, H. (2000) ‘The International Monetary Fund: Its Present Role in Historical Perspective’, NBER Working Papers No. 7724, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Boughton, J.M. (2001) Silent Revolution, Washington, DC: IMF.

Boughton, J.M. (2003) ‘Who's in Charge? Ownership and Conditionality in IMF-Supported Programs’, IMF Working Paper WP/03/191, Washington, DC: IMF.

Bowden, B. and Seabrooke, L. (eds.) (2006) Global Standards of Market Civilization, London: Routledge/RIPE Series in Global Political Economy.

Broome, A. (2006) ‘Civilizing Labor Markets: The World Bank in Central Asia’, in B. Bowden and L. Seabrooke (eds.) Global Standards of Market Civilization, London: Routledge/RIPE Global Political Economy Series, 119–130.

Broome, A. and Seabrooke, L. (2006) ‘Seeing Like the IMF: Institutional Change in Small Open Economies’, unpublished manuscript, International Center for Business and Politics, Copenhagen Business School, May.

Campbell, J.L. and Pedersen, O.K. (1996) ‘The Evolutionary Nature of Revolutionary Change in Postcommunist Europe’, in J.L. Campbell and O.K. Pedersen (eds.) Legacies of Change, New York: Aldine de Guyter, 207–251.

Clark, I. (2005) Legitimacy in International Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

de Rato, R. (2006) ‘The IMF View on IMF Reform’, in E.M. Truman (ed.) Reforming the IMF for the 21st Century, Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 127–132.

Evrensel, A.Y. (2002) ‘Effectiveness of IMF-supported Stabilization Programs in Developing Countries’, Journal of International Money and Finance 21 (5): 565–587.

Garuda, G. (2000) ‘The Distributional Effects of IMF Programs: A Cross-Country Analysis’, World Development 28 (6): 1031–1051.

Gould, E.R. (2003) ‘Money Talks: Supplementary Financiers and International Monetary Fund Conditionality’, International Organization 57 (3): 551–586.

Hall, R.B. (2003) ‘The Discursive Demolition of the Asian Development Model’, International Studies Quarterly 47 (1): 71–99.

Hobson, J.M. and Seabrooke, L. (eds.) (2007) Everyday Politics of the World Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Independent Evaluation Office (2003a) Fiscal Adjustment in IMF-Supported Programs, Washington, DC: IMF.

Independent Evaluation Office (2003b) The IMF and Recent Capital Account Crises, Washington, DC: IMF.

Jacobsson, B., Lægreid, P. and Pedersen, O.K. (2004) Europeanization and Transnational States, London: Routledge.

Leaver, R. and Seabrooke, L. (2000) ‘Can the IMF be Reformed?’, in W. Bello, N. Bullard and K. Malhortra (eds.) Global Finance, London: Zed Press, 25–35.

Momani, B. (2004) ‘American Politicization of the International Monetary Fund’, Review of International Political Economy 11 (5): 880–904.

Pauly, L.W. (1997) Who Elected the Bankers?, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Przeworski, A. and Vreeland, J.R. (2000) ‘The Effect of IMF Programs on Economic Growth’, Journal of Development Economics 62 (2): 385–421.

Rapkin, D. and Strand, J. (1997) ‘The United States and Japan in the Bretton Woods Institutions: Sharing or Contesting Leadership?’, International Journal 52 (20): 265–296.

Rapkin, D.P. and Strand, J.R. (2006) ‘Reforming the IMF's Weighted Voting System’, The World Economy 29 (3): 305–324.

Seabrooke, L. (2001) US Power in International Finance, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Seabrooke, L. (2006a) The Social Sources of Financial Power, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Seabrooke, L. (2006b) ‘Legitimacy Gaps in Global Standards of Market Civilization: The International Monetary Fund and Tax Reform’, paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Studies Association, San Diego, March 22–25.

Seabrooke, L. (2006c) ‘The Bank for International Settlements’, New Political Economy 11 (1): 141–149.

Seabrooke, L. (2006d) ‘Legitimacy Gaps in Global Economic Governance: The International Monetary Fund and Tax Reform’, book manuscript in preparation, International Center for Business and Politics, Copenhagen Business School, October.

Seabrooke, L. (2007) ‘Everyday Legitimacy and International Financial Orders: The Social Sources of Imperialism and Hegemony in Global Finance’, New Political Economy 12 (1), forthcoming.

Sharman, J.C. (2006) Havens in a Storm, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Stiglitz, J. (2002) Globalization and its Discontents, London: Penguin.

Stone, R. (2002) Lending Credibility, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Taylor, I. (2004) ‘Hegemony, Neoliberal ‘‘Good Governance’’ and the International Monetary Fund: A Gramscian Perspective’, in M. Bøås and D. McNeill (eds.) Global Institutions and Development, London: Routledge, 124–136.

Thacker, S. (1999) ‘The High Politics of IMF Lending’, World Politics 52 (1): 38–75.

Thirkell-White, B. (2004) ‘The International Monetary Fund and Civil Society’, New Political Economy 9 (2): 251–270.

Truman, E.M. (2006) ‘An IMF Reform Package’, in E.M. Truman (ed.) Reforming the IMF for the 21st Century, Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 527–540.

Vetterlein, A. (2006a) ‘Change in International Organizations: Innovation or Adaptation?’, in D. Stone and C. Wright (eds.) The World Bank and Governance, Routledge: London, 125–144.

Vetterlein, A (2006b) ‘International Organizations and Poverty’, unpublished book manuscript, Department of Social Policy and Social Work, Oxford University.

Vreeland, J.R. (2003a) The IMF and Economic Development, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vreeland, J.R. (2003b) ‘Why Do Governments and the IMF Enter into Agreements? Statistically Selected Cases’, International Political Science Review 24 (3): 321–343.

Wade, R. and Veneroso, F. (1998) ‘The Asian Crisis: The High Debt Model versus the Wall Street-Treasury-IMF Complex’, New Left Review 228: 3–23.

Woods, N. (2001) ‘Making the IMF and the World Bank More Accountable’, International Affairs 77 (1): 83–100.

Woods, N. and Lombardi, D. (2006) ‘Uneven Patterns of Governance: How Developing Countries are Represented in the IMF’, Review of International Political Economy 13 (3): 480–515.

Xu, Y-C. (2005) ‘Models, Templates and Currents: The World Bank and Electricity Reform’, Review of International Political Economy 12 (4): 647–673.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This article was drafted while a visitor at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo. It was then revised during a visit to the Center for the Advanced Study of the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS), Stanford University. My thanks go to all of the participants in this symposium, as well as to Mick Cox, for their feedback on earlier versions of this piece at both the Canberra 2005 and Bellagio 2006 workshops. My thanks also go to Jacquie Best, Anna Persson, Ole Jacob Sending, Shogo Suzuki, and Antje Vetterlein for their conversations and comments on earlier drafts. My special thanks go to André Broome for his extensive comments on earlier drafts. My thanks also go to the archivists in the International Monetary Fund Archives, Washington, DC, especially Madonna Gaudette, Premela Isaacs, and Jean Marcouyeux.

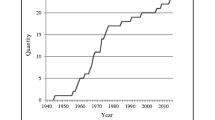

2 The hunch on templates is drawn from a broader study of the Fund and tax policy advice to 20 states between 1965 and 2000. In the broader study, the states are: Indonesia, South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, Romania, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Morocco, Egypt, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Senegal, and Zambia. A companion study on small open economies is also under development (see Broome and Seabrooke, 2006). On the Asian states alone, see Seabrooke 2006b. The broader study is under development.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seabrooke, L. Legitimacy Gaps in the World Economy: Explaining the Sources of the IMF's Legitimacy Crisis. Int Polit 44, 250–268 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800187

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800187