Abstract

One of the most significant economic developments of the past decade has been the convergence of the previously separate segments of the financial services industry – particularly the banking and insurance sectors. Convergence has been driven by increasing globalization of the financial services sector, the deregulation of financial markets, and advances in computer and modelling technologies. The shift in focus towards enterprise-wide corporate risk management solutions has created a growing demand for new risk management products. These developments provide opportunities for the traditional wholesalers of risk management products, particularly investment banks and reinsurers. The paper discusses the core competencies of banks and reinsurers and the factors needed for success in the evolving market. The discussion considers the merits of unbundling the traditional insurance value chain to create more responsive organizations and de-emphasize residual risk bearing by (re)insurers. The paper focuses on opportunities in innovative wholesale risk management products, including products that modify classic (re)insurance product models but do not access broader capital markets and risk-linked securities that access capital markets directly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most significant economic developments of the past decade has been the convergence of the previously separate segments of the financial services industry – particularly the banking and insurance sectors. Convergence has coincided with the increasing globalization of the financial services sector and has been facilitated by the deregulation of financial markets in Europe, the United States, and Japan. The development of dynamic financial markets for derivatives and other innovative securities as well as advances in computer, modelling, and telecommunications technologies have accelerated convergence. An important factor driving convergence is the increasing focus on shareholder value maximization by corporations worldwide. The resulting shift in focus from traditional risk management “silos” to enterprise-wide risk management has created a growing demand for new risk management products. These developments provide opportunities for the wholesalers of risk management products, particularly investment banks and reinsurers. This paper analyses the opportunities and challenges facing wholesale financial services firms with respect to innovative risk management products.

The remainder of the paper is divided into two major sections. The next section provides an overview of the wholesale financial services market and an analysis of the factors driving the convergence of insurance and investment banking. The emphasis throughout is on products and markets where reinsurers and investment banks are most likely to compete. The elements of the insurance value chain are discussed as well as the merits of unbundling the traditional value chain to de-emphasize residual risk bearing by (re)insurers. The further section discusses innovative wholesale risk management products categorized into two classes: (1) products that modify classic insurance and reinsurance product models but do not access broader capital markets and (2) asset-backed securities (ABS) and derivatives that access capital markets directly. Securities in the former category include various types of alternative risk transfer (ART) instruments, while securities in the latter category include catastrophe (CAT) derivatives, mortality-linked securities, and weather derivatives. Conclusions are presented in the last section.

The wholesale financial risk management market

The wholesale risk management market

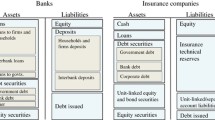

The wholesale risk management market is a business-to-business market in securities issuance, risk management, and hedging products. The market can be conceptualized as involving three essential functions – risk management or financing, risk intermediation, and risk bearing or absorption. The demand side of the market consists primarily of non-financial corporations, financial institutions, and governments with risk management and financing needs. The supply side of the market consists of various types of financial intermediaries and ultimately the capital markets. The financial intermediation function is carried out by various types of firms, including commercial banks, investment banks, brokerage intermediaries (e.g., insurance, reinsurance, and securities brokers), insurers, and reinsurers. This paper primarily considers the wholesale opportunities for investment banks and reinsurers.

Traditionally, investment banks primarily served a pure intermediation function, providing a conduit between the demand side of the wholesale market and the capital markets but bearing little risk themselves. Among the core competencies of investment banks are the design of securities that serve risk management and financing needs and the placement or sale of these securities in the capital markets. Investment banks also engage in stock, bond, and options trading and market making, correspondent clearing, proprietary trading, and investment management. In addition, investment bankers serve as advisors in mergers and acquisition transactions, privatizations, and similar deals. Investment banks also engage in hedging and risk management, primarily through the use of derivatives to enable clients to hedge risks such as interest rate risk, commodity risk, and foreign exchange risk. Through such activities investment banks have developed specialized expertise in designing and issuing securities, financial modelling, and designing dynamic hedging strategies. The convergence of banking and insurance markets provides opportunities for investment banks to leverage these skills to create value for owners.

Insurers and reinsurers, on the other hand, traditionally served a risk-absorption or risk-warehousing function with less emphasis on risk intermediation and deal making. Insurers provide risk management products but typically do not pass the risks inherent in these instruments along to the capital markets but rather hold them on-balance-sheet. Capital markets also serve as the ultimate risk-bearer in traditional insurance and reinsurance markets but this is accomplished through the ownership of insurance companies rather than investing directly in the underlying risk management products themselves. Until recently, it was very difficult for investors to make a “pure play” investment in the types of risks underwritten by insurers or reinsurers – it was necessary to take an equity or bond stake in the entire enterprise or not to participate at all.

Historically, an important reason for the risk warehousing role of the insurance industry is that traditional insurance products are not sufficiently liquid or transparent to be traded directly in capital markets. However, the technological advances and other drivers of convergence discussed below are likely to result in reinsurers moving away from their traditional risk warehousing role and towards more of a pure financial intermediation role, at least for certain types of insurance-related risk management products. Thus, convergence can be viewed as the process of moving off-balance-sheet the risks traditionally absorbed or warehoused by insurers.

In their role as risk warehousers, reinsurers traditionally provided several types of reinsurance to primary insurers, often called “ceding companies” or “cedants.” These included various types of proportional and non-proportional reinsurance covers as well as catastrophe and stop-loss contracts. More recently, reinsurers have developed innovative new products such as finite reinsurance, “blended” coverages, and multi-year multi-risk contracts, discussed in more detail below. Reinsurers also earn fee income by providing underwriting and pricing advice to primary insurers and increasingly are playing an important role in the market for securitization of catastrophic property risks, mortality risk, and other types of risk. These activities have enabled reinsurers to develop specialized expertise in insurance underwriting, pricing, and liability management that offer potential competitive advantages in certain types of risk management products as markets converge.

Drivers of convergence

Demand-side factors

There are several important factors driving the convergence of insurance and financial markets, most of which are related to changing demands for risk management products and imperfections in insurance, reinsurance, and capital markets. In modern financial theory, as it evolved during the 1970s, it is difficult to rationalize corporate risk management. Corporations are owned by diversified investors who operate in frictionless and complete markets and thus can diversify away non-market risks (unsystematic risks) on their own account. Hence, corporate management of non-market risks was viewed as a value-destroying proposition that would not benefit shareholders. As financial theory has evolved over the past two decades, there has been an increasing recognition that management of non-market risks often is value-creating for shareholders.Footnote 1

The new theory of corporate hedging has converged on the idea that it is advantageous for firms to hedge at least some of the risks that are not central to their core businesses. The argument is that managers should focus on the firm's core competencies, that is, the areas of economic activity where the firm has a comparative advantage. For example, airlines face business risks arising from their passenger and air freight operations as well as commodity price risk due to volatility in fuel prices. Airline executives can maximize value by optimizing their transportation operations and hedging-out the commodity price risk, that is, airline firms are most likely to add value by providing high-quality transportation rather than speculating in commodities. Risk management is also advantageous if internal capital is less costly than external capital, due to informational asymmetries or other factors. Costly external capital provides a motive for corporations to hedge risks that could deplete internal capital, thereby forcing them to forego projects that would be profitable at internal capital prices but not at external capital prices. Numerous additional examples could be provided, but the major point is that risk management should be conducted when it is advantageous from a cost–benefit point of view.

The types of risk that are the focus of this paper can be called non-core risks, which are broadly defined as risks that are beyond the core competencies of most firms in the economy. These are risks that must be managed or avoided in order to enable management to add value by focusing on the firm's primary activity. An important category of non-core risks encompasses risks that traditionally were managed by purchasing insurance – the risk of loss from fires, natural disasters, liability lawsuits, work injuries, and other types of accidents or legal actions. However, non-core risks also include other sources of volatility that have not traditionally been traded in insurance markets. The latter category includes weather risks, credit risks, commodity price risks, and foreign exchange risks, among others.

The focus on corporate risk management as a source of firm value has led to the emergence of the concept of holistic or enterprise risk management (ERM), perhaps the most significant demand-side driver of convergence in financial markets. Traditionally, corporations separated the insurance-related risk management functions from the financial and business risk management functions. The insurance risk-managers were responsible for purchasing insurance coverage against insurable perils. As markets have evolved, the insurance risk managers also became responsible for managing risks through self-insurance programmes and the formation of captive insurance companies. These insurance-related functions generally were separated from the firm's asset-liability management and currency and commodity hedging programmes, as well as from the firm's capital structure, dividend policy, and other corporate risk management decision-making.

The emergence of enterprise risk management has been motivated by the recognition that separation of risk management functions is not consistent with the corporate objective of maximizing shareholder value. Segmented or “silo” risk management approaches do not recognize intra-firm opportunities for the diversification of risk. Such segmented strategies thus can lead to excessive hedging expenditures by failing to identify the firm's “natural hedges” or can leave the firm exposed to too much risk by failing to recognize adverse correlations among risks. Enterprise risk management recognizes the need for coordination between insurance-type hedges and financial hedges against foreign exchange, commodity, and other risks and also creates demand for financial instruments that package together insurance and financial hedges, including the multi-risk, multi-year products discussed below.

A second demand-side driver of the convergence of banking and insurance is the growth in property values in geographical areas prone to catastrophic risk. Trillions of dollars of business and residential property exposure exist in disaster-prone areas such as Florida and California, and the capacity of the world's insurance and reinsurance markets is inadequate to fund a major catastrophic event, such as the fabled “Big One” in Florida or California.Footnote 2 There is also significant exposure to catastrophic risk in Europe and Japan, and the growth in property values in the emerging economies of Asia and other parts of the world also will increase the demand for catastrophic risk funding for many years to come. Although large catastrophic risks are beyond the capacity of insurance and reinsurance markets, they are generally quite small relative to the size of securities markets. For example, the projected $100 billion California earthquake is approximately 30 per cent of the equity capitalization of the U.S. insurance industry but less than ½ of 1 per cent of the value of U.S. stock and bond markets. The recognition that it is more efficient to finance this type of risk in securities markets rather than in insurance markets has led to the development of innovative financial instruments such as catastrophic risk (CAT) bonds and options. These products require the application of both investment banking and insurance underwriting/pricing skills and hence have been at the forefront of the convergence of insurance and financial markets.

A third set of demand-side drivers of convergence that primarily reflect market imperfections are various regulatory, accounting, and tax factors (RATs). Wholesale financial products can assist firms on the demand side of the market in complying with various regulations and avoiding regulatory costs. Risk management products also can serve tax-minimization objectives by reducing income volatility in the presence of convex tax schedules or taking advantage of specific provisions in various national tax codes. Additionally, wholesale products can be used to perform the role of “balance sheet cleansing,” that is, reducing or eliminating problematical balance sheet entries that can damage the firm's financial rating or reduce the firm's attractiveness to potential merger and acquisition partners. Such products can also be used to modify the firm's capital structure to achieve regulatory compliance or profit maximization objectives. Finally, the introduction of fair value accounting for insurance liabilities is scheduled to be implemented by the International Accounting Standards Board. Securitized insurance products have the potential to play the role of “tracking securities” in providing market valuations of various categories of insurance liabilities that otherwise are very difficult to evaluate.

Supply-side factors

Among the supply-side factors driving convergence are various imperfections in insurance, reinsurance, and capital markets. Insurance and reinsurance markets tend to function well for high-frequency, low-severity events such as automobile accidents but are less well suited to handle low-frequency, high-severity events. Insurance markets also tend to work best when dealing with uncorrelated risks but tend to break down when risks are excessively correlated. Property catastrophes provide an example of the type of low-frequency, high-severity, correlated risks that can stress insurance markets. Surges in the frequency and severity of liability insurance claims resulting from new judicial interpretations of the law or contracts also trigger events that can increase losses on past, present, and future liability insurance policies. Although such events are “systematic” risks when confined to insurance and reinsurance markets, they are closer to being unsystematic and hence diversifiable if spread throughout the economy through securitization.

Insurance and reinsurance markets are also subject to price and availability cycles. For example, Figure 1 shows the Guy Carpenter catastrophe reinsurance price index for the period 1990–2004.Footnote 3 The index (set equal to 100 in 1991) increased to more than 300 in 1992–1994, in response to losses caused by Hurricane Andrew and the Northridge earthquake. The index declined steadily from 1995 to 2000 but increased again in 2001 in response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and a general tightening of insurance and reinsurance markets. Markets for other types of insurance also are subject to cycles.Footnote 4 Cycles are driven in large part by capacity constraints stemming from informational asymmetries between insurers and the capital market that impede the free flow of capital into and out of the industry.Footnote 5 As a result, prices rise and coverage supply declines following a loss or investment shock that depletes insurer capital, triggering a hard-market phase of the cycle. As capital is gradually built up (mainly through retained earnings), a soft-market phase develops, characterized by low prices and plentiful availability of coverage. Trading securitized insurance products directly in capital markets would tend to mitigate the price cycle by eliminating informational asymmetries about the adequacy of insurer reserves and prices and providing additional risk-bearing capacity during hard markets.

Modern financial theory and improvements in computer technology are also among the factors driving the convergence of banking and insurance markets. Modern financial theory has enabled market participants to acquire a much deeper understanding of risk management transactions than ever before. These developments have been facilitated by the development of more powerful computing technologies and statistical methods. The development of sophisticated risk management models and strategies has facilitated the emergence of new financial products and also led to the widespread securitization of cash flows formerly held on-balance-sheet by financial and non-financial firms. In insurance and reinsurance, advances in computing have enabled modelling firms to build extensive databases that map insurance exposures down to the level of the individual house, providing data on construction, vulnerability to damage from catastrophes, and insurance coverage. Modelers have harnessed the insights of science to model the likelihood, strength, and impact of catastrophic events. These modelling capabilities give insurers unprecedented ability to manage their exposure to catastrophic risks.

Core competencies of investment banks and reinsurers

As suggested above, investment banks typically serve as pure financial intermediaries and advisers rather than residual risk bearers, that is, they do not usually put firm capital at risk in activities other than trading for the house account. The practice in the insurance and reinsurance industries is just the opposite, that is, such firms almost always serve as the residual risk bearers (risk warehousers), backing the promise to pay claims under the policies they issue by holding substantial amounts of equity capital.

Recently, market participants have begun to question the wisdom of maintaining the traditional residual-risk-bearing function for many types of insurance, at least in the extreme form that exists today. For example, it has become clear that it would not be efficient to solve the catastrophic loss financial problem by pouring substantial amounts of new equity capital into the non-life insurance and reinsurance markets. Such capital is costly because of regulatory, accounting, and tax rules as well as market frictions such as agency costs, moral hazard, and adverse selection.Footnote 6 Even in the absence of such capital costs, it would be neither necessary nor efficient for the funds to be held in the insurance and reinsurance industries, given the efficiency of capital markets in developed economies.

The core expertise that insurers and reinsurers bring to the risk management environment is their specialized knowledge about risk underwriting, pricing, and liability management. Insurers and reinsurers do not have any special comparative advantage at running investment portfolios or bearing residual risk. Therefore, a future evolution of insurance providers away from risk bearing and towards a more sustained focus on their core competencies of underwriting, pricing, and liability management would seem to make sense economically. For example, reinsurers could utilize their underwriting and loss portfolio management skills to put together portfolios consisting of reinsurance contracts issued to primary insurers across the globe. Such portfolios would be highly diversified but there would still be a need to handle the risk-bearing function due to the high loss volatility inherent in insurance claims. This could be accomplished by reinsurers hedging most of the remaining risk of their portfolios through derivatives contracts, reducing the need to hold as much costly equity capital. Reinsurers thus would add value through their underwriting and liability management capabilities but would serve as intermediaries between insurers and the capital markets, which would bear most of the residual risk.

The traditional risk warehouse or integrated insurer/reinsurer internalizes virtually all aspects of the insurance transaction and bears all of the risk, except for the component transferred to the reinsurance market. The integrated insurer performs an “insurance origination” function by selling insurance policies through one or more distribution channels, which can include owned (“tied”) or independent (brokerage) distribution channels, selling insurance through the internet, or providing “private label” products to banks or securities dealers.

The insurance value-chain then connects to the underwriting function, that is, the decision of whether to issue a policy. The underwriting process either results in the applicant being assigned to a risk classification category with a particular price or, in the case of large corporate risks, the determination of a unique price for the buyer. The insurer also provides risk management services such as advice about loss mitigation and risk control programmes. The integrated insurer also invests the funds obtained by issuing insurer equity and collecting insurance premiums. It also manages the liability portfolio, including managing duration and convexity risk through asset-liability management (ALM), and, also of great importance, managing loss reserves and taking steps to hedge the risk of adverse loss development. The integrated insurer manages the claims settlement process in order to settle claims expeditiously and avoid moral hazard. Finally, the insurer re-underwrites and re-prices the policy when it comes up for renewal; and, of course, performs the residual risk-bearing function. In this case, residual risk bearing takes place through capital market ownership of the insurer, that is, the capital market does not invest directly in the financial instruments issued by the insurer.

An alternative to the integrated approach to providing insurance-risk management services is an “unbundled” insurer model shown in Figure 2. The figure shows a model where product origination is conducted through a “virtual insurer” via the internet. Aside from the policy origination function, the internet insurer does not engage in any of the other activities in the insurance value-chain. Policy applications are transferred to an actuarial provider who performs the core insurance functions of pricing and underwriting/risk selection. In this example, the actuarial provider invests the premiums and equity capital, manages the liabilities generated by the issued policies, and conducts the ALM function. The actuarial provider also engages in risk diversification and hedging through purchasing reinsurance and/or insurance-linked derivatives. The coverage design, claims settlement, and loss control functions are out-sourced to a service provider specializing in the policyholder service function.

The final segment of Figure 2 concerns the residual risk-bearing function. The insurer or reinsurer is almost always the residual risk bearer in the integrated insurance model. Residual risk bearing by the insurer/reinsurer is also a possibility in the unbundled model shown in Figure 2 through the issuance of stock to raise funds to provide a solvency guarantee to policyholders. However, it is also possible to securitize the risk arising from the insurance enterprise. This could take the form of asset-backed securitization where assets are assigned to a special purpose vehicle. Non-asset-backed securitization through derivatives or other mechanisms also is a possibility. Various combinations of residual risk-bearing structures are also easy to envision, where the shareholders of the actuarial provider (or other participant) bear some residual risk, while securitizing some classes of policy liabilities. The degree to which securitization succeeds will depend upon whether market participants can overcome the informational and modelling problems that led to the prevalence of risk warehousing.

The type of organization represented in Figure 2 might make sense because the skills needed to sell products through the internet are not necessarily related to the skills needed to perform the actuarial, claims settlement, and risk-bearing functions. Of course, unbundling the functions as shown in Figure 2 has the potential to create costs due to moral hazard, because the interests of the parties engaged in different aspects of the insurance process do not necessarily coincide. Care needs to be taken to write incentive contracts protecting the residual risk bearers from the moral hazard of the policy originator, actuarial provider, and service provider. For example, the profits of the originator could be made contingent on the underwriting profitability of the policies underwritten. This type of incentive contract traditionally has been quite common between insurers and insurance brokers. Similar incentive arrangements could be established with the service provider to mitigate incentives to settle claims carelessly. Finally, because the actuarial provider has perhaps the greatest influence over the profitability of the enterprise, it might make sense for the actuarial provider also to participate in residual risk bearing.

The model shown in Figure 2 has implications for the convergence of insurance and banking by helping to identify the functions that form the core competencies of insurers. The unique skills that insurers bring to the table in the converging market place are underwriting and risk selection, pricing, and liability management. The pricing of insurance and risk management instruments sold to corporate clients is especially difficult because of the complexity and uniqueness of corporate risk exposures and the necessity for projecting loss cash flows many years into the future. It is difficult to foresee all of the contingencies that could generate losses under an insurance contract. The horror stories of the asbestos and environmental claims facing many U.S. insurers as well as the totally unanticipated mega-losses from the September 11 World Trade Center attack are cases in point.Footnote 7 Finally, the management of non-life insurance loss reserves is a very risky and critically important function.

The core competencies of insurers and reinsurers are also important in insurance securitizations. A deep understanding of the underlying stochastic processes characterizing insurance claims is necessary in order to credibly structure such deals.

Performance of the core insurance-management functions is essential for the success of any insurance-related venture, and these skills are not easily acquired. It would be difficult for a new entrant to acquire the degree of experience and knowledge to compete effectively with top international reinsurers. Of course, such knowledge could be obtained by buying an existing reinsurer, and this would be one way for an investment bank to become a player in this market. Perhaps more consistent with the culture of the investment banking community would be the development of strategic alliances with reinsurers whereby the investment bank would perform the tasks that constitute its core competencies and the reinsurer would perform the underwriting, pricing, and liability management functions.

It is interesting to compare the core competencies of insurers and reinsurers with those of the investment bank through a brief discussion of the function of securities issuance. The origination function in this case would come in the form of contacts generated by the bank's reputation and its previous relationships with securities issuers and other financial institutions. The bank essentially works with the client to develop a new security offering that satisfies a particular financing or risk management need. This could include initial public offerings, seasoned offerings of debt or equity securities, or securitization of existing assets, liabilities, or cash flows.

As an example of investment banking, the issuance of an initial public offering (IPO) of equity securities is diagramed in Figure 3. The investment bank works with the corporate client to develop the IPO. This involves structuring the transaction, taking the necessary steps to comply with securities laws and regulations, including the preparation of the offering prospectus, developing the offer prices, and then marketing the securities to investors. Investors can include corporations, financial institutions, private clients, and the investment bank's house account. The proceeds from the issue are channelled through a trustee/custodial account. The trustee receives the funds from investors, pays the investment bank its fee, and supplies the net proceeds of the transaction to the client. The investment bank's risk-bearing function is entirely discretionary and usually incidental to the bulk of the funds raised in the transaction. The bank's core competencies of structuring, compliance, pricing, and placement of the securities issue are not easily duplicated by other types of financial services firms.

Although some major reinsurers are attempting to enter the converging market as full service reinsurance/investment banking firms, many of the deals to date seem to resemble reinsurance products more closely than investment banking products. However, it is conceivable that one or more of the well-positioned reinsurers will be able to make the transition. The general prediction is that reinsurers will succeed in offering products that involve their core competencies, that is, which incorporate significant elements of present-day reinsurance products, whereas the investment banks will be relatively successful in marketing products that resemble securities more closely than they do reinsurance.

One area where reinsurers have gained some success is in the market for credit-related products, including traditional products such as credit insurance and credit derivatives such as credit-linked notes and swap agreements. One reason that reinsurers have succeeded in the credit derivatives market is that the models used to price credit risk products are very similar to traditional actuarial models. For example, the CreditRisk+ model developed by Credit Suisse Financial Products is very similar to the actuarial models used in pricing property-liability insurance.Footnote 8 Hence, it is natural for reinsurers to participate in markets where they have existing modelling capabilities.

Success factors for financial wholesalers

The market for wholesale financial services has evolved significantly away from the relatively simple financial instruments that traditionally were offered by investment banks and reinsurers, towards a richer set of products combining formerly separate risk elements. The modern wholesale market is also more international than ever before. The institutions that succeed in this dynamic and rapidly evolving market will be those that develop the necessary inter-disciplinary skills that enable them to respond quickly and effectively to emerging risk management needs.

To operate in today's financial wholesale market, a firm must have an international presence with operating subsidiaries that can move quickly to take advantage of opportunities in various parts of the world. This implies that the wholesaler needs to have licensed insurance and banking subsidiaries in all of the major geographical areas where it expects to be able to operate. Care must be taken to maintain high-quality financial ratings to give the subsidiaries credibility as counterparties for hedging transactions. A successful financial wholesaler also will need in-house expertise in a variety of areas. On the regulatory/compliance side, the firm needs expertise in legal, accounting, and tax rules and regulations. The regulatory compliance area is particularly challenging, given the historically different approaches taken by bank and insurance regulators. On the financial side, expertise is required in financial products, financial engineering, actuarial science, insurance underwriting, and risk engineering. Because of the wide range of skills needed to operate in the wholesale financial services market, it is also important to establish responsive organizational structures and appropriate incentive systems within the firm. This element is needed to facilitate optimal interactions among experts from different specializations and cultures to achieve the overall objectives of the firm. The organizational structure needs to be professionally oriented rather than bureaucratic in order to enable the firm to respond quickly to the emerging risk management needs of its present and prospective clients.

Modelling and pricing of innovative wholesale financial products is one of the most important critical success factors. The new products are relatively difficult to price because they combine elements from previously separate financial products. In addition, widely accepted pricing models do not exist for many of the new securities, and the data available to test pricing models for securities such as CAT bonds tend to be limited and of poor quality. The pricing step is particularly important in the area of securitization. One of the reasons why reinsurers traditionally served primarily as risk warehousers was their superior expertise in underwriting and pricing insurance risks. This informational asymmetry between reinsurers and capital markets largely prevented reinsurers from playing a pure intermediation role and discouraged the securitization of insurance-lined risks. Only by overcoming the limitations of pricing technology and data quality can the insurance-linked securitization market achieve its potential.

Innovative wholesale risk management products

An indication of the opportunities in the converging market for banking and insurance services can be provided by examining some of the new and innovative products that have been introduced during the past several years. The products can be grouped into two major categories: (1) alternative risk transfer (ART) products that have evolved out of traditional insurance and reinsurance arrangements; and (2) insurance-linked securities and similar products on the so-called “exotic underlyings.” ART products do not expand the available capital base very much beyond existing insurance and reinsurance markets, whereas insurance-linked securities enable hedgers potentially to access the entire global capital market. As this distinction suggests, the ART products serve a valuable market function, but it is securitization that has the greatest potential to transform the market for pure risks beyond insurance and reinsurance to create a thriving new class of assets that can be traded on the world's securities markets.Footnote 9

ART products

The ART market in turn can be divided into two classes of activities: (1) institutions that supplement or parallel the insurance and reinsurance markets, and (2) products that expand or adapt conventional reinsurance contractual forms to cover new risks or to package existing risks in new and innovative ways. The former category includes corporate self-insurance programmes, captive insurance companies, and other buyer-sponsored plans such as risk retention groups (RRGs). The latter category consists of products that extend conventional reinsurance, for example, to cover risks not included in traditional reinsurance covers, to permit time diversification, to pay off based on multiple event triggers, and to serve financing as well as risk indemnification objectives. Since the self-insurance and captive insurance company markets are relatively mature and reached their present state of evolution prior to the major emergence of banking-insurance convergence, these approaches are not discussed in this paper.Footnote 10

Finite risk reinsurance

Finite risk reinsuranceFootnote 11 is an important ART product, often used to provide income smoothing for primary insurers with limited assumption of risk by the reinsurer, and resembles a combination of a multi-year banking transaction with limited reinsurance coverage. Finite risk reinsurance has five distinguishing features: (1) Risk transfer and risk financing are combined in a single contract. (2) The amount of underwriting risk transferred to the reinsurer is less significant than under conventional reinsurance contracts.Footnote 12 (3) Finite risk contracts almost always cover a multi-year period rather than being annually renewable as are conventional reinsurance contracts. (4) Investment income on the premiums paid by the primary insurer (cedant) is explicitly included when determining the price, placing an emphasis on the time value of money not found in conventional reinsurance. (5) There is usually risk-sharing of the ultimate results (positive or negative balance at the end of the contract) between the reinsurer and the buyer.

Finite reinsurance represents an aspect of financial sector convergence in that the reinsurer absorbs more credit risk than under an annually renewable contract, because of the possibility that the cedant will default on its agreed-upon premium payments, and also exposes the reinsurer to interest rate risk because the investment income feature usually involves some sort of interest guarantee. The premium payments or claim payments under the policy may also be denominated in some currency other than the reinsurer's home country currency, exposing the reinsurer to foreign exchange risk.

Spread loss treaties A spread loss treaty is a type of finite risk reinsurance designed to reduce the volatility of the ceding insurer's underwriting profit over time. To achieve this goal, the cedant enters into an agreement with the reinsurer that involves the payment of an annual fixed premium. Under the contract provisions, the primary company borrows money from the reinsurer when its underwriting results are adverse due to unexpectedly high insurance losses and repays the “loan” when losses are relatively low. The premium is deposited into an “experience account” each year, the account is credited with interest, and losses are deducted. Because the experience account is usually carried “off-balance-sheet,” the arrangement has the effect of smoothing the ceding insurer's reported income.Footnote 13

The arrangement is distinguished from being merely a “savings account with a credit line” because the reinsurer typically bears significant underwriting risk. That is, if the balance is negative at the end of the multi-year contract term, the reinsurer is liable for part of the balance, usually defined as Min[Max(−αB,0),D], where α is the a proportion between zero and 1, B is the experience account balance, and D is the cap on the reinsurer's obligation. There is also often a limit on the amount the reinsurer would have to lend in any given year due to unexpectedly high losses. In addition to smoothing underwriting results, these contracts provide the cedant with protection against the reinsurance underwriting cycle. Because the annual premium is usually set for the entire period of the contract, the cedant is not vulnerable to renewing the contract on unfavorable terms if the cycle enters a hard market phase.

Spread loss reinsurance is an example of a hybrid banking/reinsurance transaction that could conceivably be executed by a commercial or investment bank. However, issuing this type of product would probably expose the bank to the possibility of being regulated as an insurer, unless that contract were set up in such a way that the bank would bear no liability other than that created by the default of the buyer, that is, any risk transfer component would have to be securitized or carried by a licensed (re)insurer. In addition, the insurance component of the contract is obviously of interest to the cedant, otherwise the cedant would be better off taking out a line of credit from a bank. However, banks generally do not have the expertise needed to price the insurance risk part of the transaction and thus would be at a competitive disadvantage, regulatory issues aside. Blending banking and insurance elements in this way might be a natural function for financial holding companies and universal-bank type organizations that offer banking and insurance services out of the same organization.

Retrospective excess of loss covers Retrospective excess of loss covers (RXLs) (also called adverse development covers) are a finite risk product that protects the cedant against adverse loss reserve development in lines such as commercial liability insurance, where claims settlement covers a considerable period of time. RXLs provide retrospective reinsurance protection because they apply to coverage that has already been provided rather than coverage to be provided in the future, as under prospective reinsurance contracts. To provide background in understanding the role of RXLs, it is useful to briefly discuss the concept of reserve development, using liability insurance as an example. Under occurrence-based liability contracts, the insurer covers policyholders for all covered events taking place during the coverage period that give rise to liability claims during any future period. Policy coverage is usually for a 1-year period known as the accident year. At the end of the accident year, the insurer typically knows about only a small fraction of the claims that eventually will be filed under the policy. Thus, it must set up a reserve both for claims already filed with the company and unknown but covered claims that will be filed in the future, that is, the incurred but not reported (IBNR) reserve. The IBNR reserve is especially risky because both the frequency and severity of the covered claims are unknown, whereas only the severity of the claim is unknown for claims that have been filed. Over time, the uncertainty about covered claims is gradually resolved as claims are closed and more claims are filed, reducing the amount of the IBNR. This resolution process is called loss reserve development.

Adverse loss reserve development poses a significant risk to liability insurers,Footnote 14 and RXL covers are designed to transfer some of this risk to a reinsurer. RXLs provide partial coverage for the primary insurer if reserves exceed a level specified in the contract and thus can be conceptualized as a call option spread written by the reinsurer and purchased by the cedant. If developed losses incurred exceed the retention (striking price) specified in the contract, the cedant receives payment from the reinsurer to partly defray the costs of the adverse development. The price is based on the discounted value of the reinsurer's expected costs, and the reinsurer may assume some liability in the event that one or more of the cedant's other reinsurers defaults on its obligations. Thus, the reinsurer assumes underwriting risk, timing risk (the risk that the claims will be settled faster than recognized in the discounting process), interest rate risk, and credit risk, extending coverage significantly beyond conventional reinsurance.

Besides transferring risk, RXLs have the less obvious advantage of mitigating a significant source of asymmetrical information between the cedant and the capital market. An insurer's managers inevitably know much more about the firm's reserve adequacy and probable future reserve development than the capital market. This creates a “lemons” problem in which the insurer may have difficulties in raising capital or participating in the corporate restructuring market due to uncertainty regarding its reserves. However, one of the core competencies of a reinsurer is the ability to evaluate the adequacy of insurance prices and loss reserves. The reinsurer can leverage this knowledge to create value for its owners by writing RXL reinsurance. Besides cushioning the impact of adverse reserve development, issuing such a contract provides a signal to capital markets that a knowledgeable third party has evaluated the cedant's reserves and is willing to risk its own capital by participating in the risk. The uncertainty resolution can reduce the cedant's cost of capital and make the insurer a more attractive merger partner.

Loss portfolio transfers With RXL contracts, insurers transfer reserve development risk to the reinsurer, but retain the subject loss reserves on its own balance sheet. A finite risk cover that restructures the cedant's balance sheet is the loss portfolio transfer (LPT). In an LPT, a block of loss reserves is transferred to the reinsurer in exchange for a premium representing the present value of the reinsurer's expected claim payments on the policies included in the reserve transfer. Because loss reserves are usually carried at more or less undiscounted values on the cedant's balance sheet, the value of the reserves transferred exceeds the premium payment. This has the effect of increasing the cedant's current underwriting income and decreasing its leverage (liabilities to equity ratio). An LPT accomplishes a number of objectives including reducing the cedant's cost of capital, making it more attractive as a merger partner, permitting it to avoid costly runoff operations, and enabling the cedant to focus on new opportunities. Although the transferred reserves are usually carried on the reinsurer's balance sheet, there is no reason why they could not be securitized, provided that regulatory issues could be resolved.

Finite quota share reinsurance Finite quota share reinsurance involves the proportionate sharing of the premiums and losses of a block of business. Finite quota share reinsurance differs from ordinary quota share reinsurance primarily in placing some limit on the risk exposure of the reinsurer. An example of a quota share reinsurance transaction would be the transfer of part of the cedant's unearned premium reserve to the reinsurer in return for a ceding commission.Footnote 15 This is often motivated by accounting rules that require the insurer to set up an unearned premium reserve based on total premiums received even though most of the acquisition and underwriting costs are paid at policy issue. Thus, issuing new business leads to an artificial increase in the insurer's leverage ratio, which is mitigated through quota share reinsurance because the ceding commission enables the cedant to recapture its prepaid underwriting expenses. The “finite” aspect of the transaction is often imposed by linking the commission to the loss experience on the business transferred and/or placing an overall limit on the reinsurer's liabilities for losses under the loss sharing agreement. Finite quota share reinsurance thus serves a financing function, enabling insurers to grow more rapidly without incurring regulatory penalties for excessive book-value leverage ratios and also can smooth the volatility of underwriting results.

Blended and multi-year, multi-line products

Reinsurers are also issuing blended covers, which combine elements of both conventional and finite risk reinsurance contracts. Although motivated to some extent by regulation, which often disallows finite risk solutions as legitimate reinsurance transactions unless they involve a significant shifting of underwriting risk to the reinsurer, the principal objective of blended covers is to combine the non-traditional risk-management features of finite risk reinsurance with the more significant underwriting risk transfer offered by conventional reinsurance. Thus, blended covers may cover multiple years, insulating the cedant from the reinsurance cycle, and usually involve the recognition of the time value of money. Such contracts also may involve the transfer of foreign exchange rate risk and timing risk.

The ultimate evolution of reinsurance away from conventional yearly renewable contracts that primarily transfer underwriting risk towards contracts that protect the cedant against a wider variety of risks is represented by various types of integrated or structured multi-year/multi-line products (MMPs). In conventional reinsurance, the cedant purchases separate, annually renewable reinsurance contracts covering underwriting risk for each line of insurance. MMPs modify conventional reinsurance in four primary ways: (1) by incorporating multiple lines of insurance in the same policy, (2) by providing coverage at a pre-determined premium for multiple years, (3) by including hedges for financial risks as well as underwriting risks, and (4) by sometimes covering risks not traditionally considered insurable such as political risks and business risks.Footnote 16 This has the effect not only of providing very broad risk protection for the cedant but also of lowering transactions costs by reducing the number of negotiations that must be completed to execute the cedant's risk management program.

The price of an MMP also may appear favourable relative to the separate reinsurance agreements with multiple reinsurers, because the issuer of the MMP can explicitly allow for the diversification benefits of covering several lines of business whose losses are not perfectly positively correlated. MMPs can be conceptualized as “cross-selling” at the wholesale financial services level. As in the case of retail financial services, however, it is not necessarily the case that “cross-selling” dominates “cross-buying,” that is, the practice of buying from the best producer of each product purchased. Nevertheless, it is likely that MMPs will have a significant role to play as the risk management market continues to evolve.

An example of an MMP contract is a contract covering a cedant for auto liability, homeowners, products liability, and workers' compensation claims for a period of 5 years. The premium would reflect the discounted value of the reinsurer's expected claim payments at a guaranteed discount rate, thus insulating the buyer from interest rate risk. The contract also could be designed such that the reinsurer absorbs exchange rate risk if the cedant is required to make loss payments denominated in multiple currencies. The MMP also can be designed to hedge commodity price risk, for example the “demand surge” in the cost of construction materials following a catastrophe. Because of its multiple year feature, the MMP contract also provides protection from the vagaries of the reinsurance underwriting cycle.

Multiple-trigger products

Going even further beyond conventional reinsurance policies are multiple-trigger products (MTPs). MTPs reflect the principles of “states of the world” theory from financial economics, which holds that payments in some states of the world will trade at higher (lower) prices depending upon the overall market outcome. MTP reinsurance recognizes that payments to the cedant by the reinsurer are more important in states of the world where the cedant has suffered other business reversals in comparison with states when the cedant's net income is relatively high. Thus, the payment under the MTP contract depends upon an insurance event trigger and a business event trigger, both of which must be activated before the cedant receives payment. For example, an MTP contract might cover the cedant for catastrophic hurricane losses in Florida that occur simultaneously with an increase in market-wide interest rates. The cedant would thus be protected against having to liquidate bonds at unfavourable prices to pay insurance claims resulting from the catastrophe, but would not have to pay for protection covering circumstances in which a catastrophe occurs when securities market conditions are more favourable. Another example is a contract covering an electric utility company against the dual event of a power outage at a time when electricity prices are unusually high.

In effect, MTPs combine conventional reinsurance protection and financial derivatives in a single, integrated contract. In the homeowners example, the MTP product combines reinsurance protection with an embedded interest rate derivative. Because the probability of the simultaneous occurrence of an interest rate spike and a property catastrophe is low, the MTP product is likely to be priced considerably below a catastrophe reinsurance policy, thus enabling the cedant to direct its hedging expenditures to cover events for which the pay off of the hedges has the highest economic value.

ART products: conclusions

These alternative risk transfer instruments clearly extend traditional reinsurance and provide good examples of the convergence of insurance and financial markets. However, there are a few caveats to be kept in mind when considering these contracts:

-

1)

Most of the contracts implicitly assume the existence of market imperfections and unexploited arbitrage opportunities. In a complete markets setting with more or less perfect information, most of these contracts would not be viable. For example, financial quota share reinsurance seems to be motivated primarily by regulatory accounting rules. Similarly, spread loss reinsurance would not be attractive if external capital were not more costly than internal capital. If priced in efficient financial markets, a loss portfolio transfer should not change the stock market equity valuation of either the insurer or the reinsurer. That is, market imperfections such as regulation and imperfect information create the “gains from trade” in many of these transactions.

-

2)

Insurance/financial markets may evolve away from rather than towards highly structured, relatively opaque products such as MMPs. Among other potential limitations, these contracts typically access the capital of a single reinsurer. Even though the reinsurer can lay off some of the risks in a retrocession, MMPs as presently structured do not bring new risk-bearing capital into the market. The fact that MMPs are complex, dealing with multiple lines and a variety of financial risks, would seem to make them more difficult to securitize than more transparent products, limiting their growth potential.

-

3)

The fact that recognition of the time value of money is heralded in the reinsurance market as an innovation speaks volumes about the entrenched culture of the insurance and reinsurance industries and indicates that convergence still has a long way to go to achieve truly efficient markets.

-

4)

In principle, many contracts that incorporate both insurance and financial risks could be replicated by separately trading insurance derivatives and financial derivatives. In this case, the value added from constructing the hedge could be uncoupled from the need for a residual claimant such as a reinsurer. However, contracts that pay off based on joint underwriting and financial triggers serve an important economic need and have significant potential for future growth.

Securitized risk transfer products

This category consists of various arrangements that securitize underwriting risk as well as derivatives on “exotic underlyings” such as weather risk, and relatively new securities such as collateralized bond obligations, where investment banks and reinsurers compete for business. Securitization involves the repackaging and trading of cash flows that traditionally would have been held on-balance-sheet by financial intermediaries or industrials. Securitizations generally involve the agreement between two parties to trade cash flow streams to manage and diversify risk or take advantage of arbitrage opportunities. The cash flow streams to be traded often involve contingent payments as well as more predictable components that may be subject to credit and other types of counterparty risk. Securitization provides a mechanism whereby contingent and deterministically scheduled cash flow streams arising out of a transaction can be unbundled and traded as separate financial instruments that appeal to different classes of investors. Securitization transactions facilitate risk management and add to the liquidity of financial markets by creating new tradable financial instruments.

Most of the securitized transactions that provide convergence opportunities for investment banks and reinsurers fall into two primary categories: (1) non-traditional asset-backed products such as credit securitizations and securitizations of cash flows from life insurance and annuity products, and (2) non-asset-backed products such as options on unconventional underlyings such as catastrophe and weather risk. The market for ABS began during the 1970s with mortgage securitizations but has grown dramatically in recent years both in volume and in the variety of securitized cash flow streams. The value of outstanding non-mortgage ABS has grown from about $320 billion in 1995 to $1.8 trillion in mid-2004. Home equity and credit card loans are the most important categories, followed by auto loans and collateralized bond and debt obligations (CBOs and CDOs). The amount of insurance-related ABS is still small in comparison with the market as a whole. However, the rapid growth of other types of ABS and the large volume of assets and liabilities carried on-balance-sheet by insurers suggests that the potential exists for significant expansion of the insurance-linked market.

Securitization design overview

The basic structure for most ABS and structured notes is diagramed in Figure 4. The process begins with a product transaction such as the sale of insurance policies or physical assets such as automobiles to customers, the issuance of a loan or mortgage, etc. Instead of retaining the resulting assets and liabilities on-balance-sheet, the originator of the transaction sells all or part of the product cash flows to investors to raise cash for operations, to transfer a risk associated with an asset or a liability to investors, or to achieve regulatory, accounting, or tax objectives. If risk hedging is part of the process, there may be various options that are part of the transaction, provided by the investors to the originator. In such cases, the sponsor is looking to sell specific risks to investors in exchange for an enhanced fixed-income return in the form of an option premium. The risk that the sponsor is looking to transfer could be the risk of economic downturns on cash flows, credit deterioration in a loan portfolio, or catastrophic property claims from an insurance portfolio. If investors value the option as a diversifying asset, the risk premium that they demand for underwriting the option risk will be lower than the internal funding costs of a sponsor that has a concentration of this risk, providing the gains from trade that make the transaction economically viable. ABS transactions usually involve the use of a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which holds the funds provided by investors and owns the rights to the securitized cash flows. The existence of the SPV, which is a legally separate entity from the originator, helps to ensure that investors are protected against the bankruptcy risk of the sponsor, to provide for transparent servicing of the assets/liabilities, to structure and collateralize various tranches of debt, and to provide tax and accounting benefits to the sponsor. All of these functions tend to be deal specific. In addition, the SPV insulates the investors from the agency costs and risks of the firm's other operations, creating a “pure play” in the subject cash flows.

Such transactions also often involve an interest rate swap, usually with a third-party but sometimes with the originator. Any funds raised in the transaction are held in the SPV and invested in safe securities such as Treasury bonds. The fixed rate of return on Treasuries is swapped with a swap counterparty for a guaranteed floating rate payment, usually based on the London-Interbank-Offer Rate (LIBOR). The swap transaction shields the investors from interest rate risk and may also protect against other types of risk involving the securitized cash flows. In addition, other forms of credit enhancement may be associated with the transaction such as a financial guarantee or “wrapper” that raises the credit rating of the securities issued by the SPV. The credit enhancement function is another area where banking and insurance markets are converging. Credit enhancement is been provided by banks, reinsurers, and insurers that specialize in financial guarantees. By raising the credit rating of the transaction, the credit wrapper protects investors and lowers the cost of the transaction to the issuer.

The basic structure of non-asset-backed securitizations also can be considered reasonably generic, generally taking the form of a call option spread or a put option, but with a significant amount of variability in the details of specific issues. Such contracts can differ in a number of ways, including the underlying asset, liability, or event that is securitized, the types of risk covered by the option, and the definition of events that trigger payment under the contract. Among the more exotic underlyings that have been optioned in recent years are contracts paying off in response to credit defaults, catastrophic property events, and weather risks.

The discussion now turns to some of the more interesting non-traditional securitizations that provide opportunities for financial services wholesalers. The objective is not to present an exhaustive survey but rather to give some examples to illustrate the types of instruments that have been offered.Footnote 17

Credit-linked securities

Significant convergence between financial services wholesalers has occurred in the market for credit-linked securities. As the use of credit derivatives to buy and sell credit risk has expanded, some institutions have started issuing instruments that combine traditional fixed income securities with an embedded credit derivative within the same structured note. While these credit-linked notes have taken many forms, the basic premise is simple: a credit-linked note provides investors with the opportunity to invest in the return associated with a particular entity's credit risk. To the extent that such securities represent non-redundant assets, they enable investors to improve the efficiency of their investment portfolios by investing in risks not previously available or in pure play securities that separate credit risks from the other business risks and agency costs of the issuers.

One of the principal drivers of the market for credit-linked notes is investor demand for bypassing regulatory restrictions on credit risk underwriting and risk-taking. For example, participation in the bank loan market is restricted to regulated financial institutions in most countries. Therefore, until the creation of the credit-linked note market, investors in other industries could not diversify their risk exposure to the bank credit market. With the advent of credit-linked notes, a wide variety of institutional investors can invest in bank loan credit risk.

Important types of credit-linked notes include: (1) Traditional structured notes, where the coupon or principal is indexed to the credit risk performance of an underlying reference credit. Such structures have many variations, including returns based on the total return of the reference credit, returns based on the spread between the reference credit and a market return (e.g., AA bond curve), and a return indexed to a credit default event. (2) Synthetic bonds that use embedded credit derivative structures to replicate the fixed income security characteristics and credit exposure of the underlying reference credit. Under synthetic bonds, the investor receives a fixed income return provided that the reference credit does not experience a “credit event” (e.g., bankruptcy). If the reference credit does have a default event, the investor's return would be adjusted to reflect the recovery value of the reference credit's debt.

To illustrate, an investor in a total return credit-linked note is essentially entering into two simultaneous transactions. First, the investor invests in a floating rate note (FRN) indexed to a market return like the LIBOR. Then, at the same time, the investor matches the terms of the floating rate note with a total return swap whereby the investor pays the FRN LIBOR and earns a rate of interest tied to the underlying reference credit. As such, the return earned by the investor matches the total return associated with the reference credit. Credit spread structured notes mirror the total return structured notes except that the investor enters into a credit derivative linked only to the basis risk between the reference credit and an underlying index. As such, the investor is only exposed to the relative credit performance of an underlying reference credit to the market index. In both the total return swap and credit-spread structures, the investor is able to leverage his return and to short the underlying index.

In a credit-linked note with a credit default swap, the investor purchases a portfolio of assets and then simultaneously enters into a credit default swap agreement with respect to a referenced credit asset. In this case, the return to the investor matches the portfolio of assets held in the structured note trust until such time as the reference credit experiences a credit default event. When this occurs, the trust has the right to substitute the “impaired” debt of the reference credit for the assets in the trust and the investor earns a return linked to the defaulted reference credit.

Synthetic bond structures are designed to replicate an investment in a given company's debt without having to purchase that company's debt. For example, J.P. Morgan structured a synthetic bond that paid investors a return (Treasury+65 bps) designed to replicate the return on Wal-Mart debt. The advantage of purchasing a synthetic bond, rather than directly purchasing Wal-Mart debt, is that Wal-Mart never actually had to issue any debt. The investor also can obtain structuring advantages such as an enhanced credit rating through the design of the structured note.Footnote 18

Reinsurers have been active participants in the credit-securities market, in part because of the modelling similarities between traditional insurance products and credit securities. Credit securities also resemble traditional credit insurance, which is also customary product for insurers. An important difference between credit risk and most traditional insurance risks is that credit risk has a stronger systematic relationship with economic conditions, implying that diversification across multiple contracts is less effective in reducing the risk of a credit portfolio. In this respect, credit-linked securities are somewhat analogous to CAT securities, which also involve correlated risks. Unlike CAT risk, however, reinsurers do not necessarily have a core competency in evaluating systematic credit risk. Thus, to participate in this market successfully, reinsurers need to invest in the knowledge creation and infrastructure required to evaluate these risks.

Insurance-linked securities

The primary impetus for the development of products that securitize underwriting risk was a surge in the frequency and severity of catastrophic property claims in the late 1980s.Footnote 19 The most important event triggering the insurance-linked securities (ILS) market was Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which cost the global insurance/reinsurance industry approximately $20 billion and led the industry to drastically revise its expectations regarding the potential magnitude of catastrophe claims. These expectations were reinforced 2 years later by the Northridge earthquake, which resulted in about $17 billion in insured losses. The worst years for insured catastrophe losses subsequent to 1992 were 1999, when insurers sustained $36 billion in losses, and 2001, where losses exceeded $38 billion due to the World Trade Center terrorist attack.Footnote 20 Catastrophe losses rose to a new level in the late 1980s. From 1970 to 1986, total insured catastrophe losses never exceeded $10 billion per year. However, losses have exceeded $10 billion in nearly every year since 1986. The higher losses are primarily attributable to an accumulation of insured property values in disaster-prone areas, particularly California and Florida in the U.S., rather than to an increase in the frequency or severity of storms or earthquakes.

As catastrophe losses grew, it became apparent that the capacity of the world's insurance and reinsurance markets was inadequate to deal with the largest events.Footnote 21 For example, although reinsurance coverage for relatively small catastrophes seems to be available, the coverage for the largest events tends to be limited. FrootFootnote 22 analyzed the percentage of the marginal exposure reinsured as a function of the size of industry-wide loss events and found that about 50 per cent of the marginal increase in industry-wide losses from $1.5 to $2.0 billion would be reinsured. However, marginal reinsurance coverage declines dramatically as a function of event size and is less than 20 per cent for events larger than $8 billion. Although market capacity has increased since the time of his study, it is likely that capacity is still limited for relatively large events.Footnote 23

Securitization has the potential to significantly improve efficiency in the financing of catastrophic risk. Although a $100 billion catastrophe amounts to about one-third of the resources of the international reinsurance industry, a loss of this magnitude is less than ½ of 1 per cent of the value of assets traded in U.S. securities markets. Securities markets also are more efficient than insurance markets in reducing information asymmetries and facilitating price discovery. Finally, because natural catastrophes are zero-beta events, CAT securities provide a new source of diversification for investors.

CBOT CAT options The first CAT-linked securities were the CBOT futures contracts introduced in 1992. These contracts evolved into call option spreads, settled on loss indices compiled by Property Claims Services (PCS). Contracts trading on nine indices were offered – a national index, five regional indices, and three state indices (for California, Florida, and Texas). The indices were based on PCS estimates of catastrophic property losses in the specified geographical areas during quarterly or annual exposure periods. Even though the CBOT CAT options are no longer listed, it is useful to briefly discuss the contracts because they are likely to provide a model for future insurance-linked options.

The CBOT were as Asian call option spreads. Asian options are based on accumulations or averages of the underlying financial instrument or index rather than the value of a price or index at the exercise date. Because there is no natural price for catastrophe risk, the CBOT options were an early example of derivatives on “exotic underlyings,” that is, the options themselves are fairly standard derivatives contracts, but the settlement trigger is unconventional. The CBOT indices were defined as accumulated catastrophe losses in specified geographical regions, over specified time periods, divided by $100 million. As an example, a “20/40 September Eastern call spread” would be in the money if the PCS index for the Eastern region of the U.S. accumulated to more than $2 billion (20 points). Each index point was worth $200 on settlement so that one 20/40 call would have paid a maximum of $4,000 (20 points times $200 per point). There are several reasons why the CBOT options were unsuccessful (discussed further below) including insurer unfamiliarity with the contracts, the perception among insurers that the contracts were subject to excessive basis risk, and a soft reinsurance market during the late 1990s that reduced the incentives for insurers to seek alternative hedging approaches.

CAT Bonds: structure Most successful insurance-linked securitizations have involved CAT bonds, which are ABS with embedded CAT options. The market appears to have begun with a CAT bond issuance by American International Group's Combined Risks division in 1996.Footnote 24 The market accelerated with issues in 1997, perhaps the most noteworthy being the first Residential Re transaction executed by United Services Automobile Association (USAA). Since that time the market for CAT bonds has grown steadily (see Figure 5). By 2003, $2.2 billion of bonds were outstanding, and new issuance volume doubled between 2002 and 2003. Although the volume of risk capital is still small relative to the capitalization of insurance and reinsurance markets, the CAT bond market has the potential to expand significantly beyond its current scale.

Most of the CAT bonds issued to date have been tailored to the needs of the issuer rather than standardized like the CBOT options. The structure of a typical CAT bond is shown in Figure 6. CAT bonds are issued by hedgers (insurers or non-financial firms) to manage their catastrophic risk. The bonds are purchased by investors, and the proceeds are placed in a single-purpose reinsurer (SPR). The SPR invests the proceeds of the bond issue in safe securities such as Treasury bonds. Since the sole purpose of the reinsurer is to hold the proceeds of the issue and make any contingent payments called for by the contract, a CAT bond issue is free of credit risk and does not alter the issuer's capital structure, being an off-balance-sheet transaction.Footnote 25 The investors receive interest from the Treasury bonds in the trust plus a spread paid by the insurer. Spread premiums typically are in the range of 300 to 600 basis points.

A CAT bond incorporates an embedded call option that is triggered by a defined catastrophic event. Usually, multiple triggers are used, for example, the option might be triggered if the insurer suffers a loss of at least $500 million from a catastrophic loss in a specified geographical area, resulting from a category 3, 4, or 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale. In a principal at risk bond, the option allows the insurer to withdraw some or all of the principal from the SPR, usually as a function of the magnitude of its catastrophe loss.Footnote 26 Some issues also include principal protected tranches, where the return of principal is guaranteed. In this tranche, the triggering event would affect the interest and spread payments and the timing of the repayment of principal. For example, a 1-year CAT bond subject to the payment of interest and a spread premium might convert into a 10-year zero coupon bond that would return only the principal. Principal-protected tranches have become relatively rare. If the defined catastrophic event does not occur, the principal and interest are returned to the investors at bond maturity.

CAT bond triggers CAT securities have been structured to pay off on three types of triggers – insurance-industry catastrophe loss indices, insurer-specific catastrophe losses, and parametric indices based on the physical characteristics of catastrophic events. Index-linked or parametric CAT bonds can be contrasted with issuer-specific contracts in terms of their exposure to moral hazard and basis risk.Footnote 27 Index-linked and parametric CAT bonds are superior to issuer-specific bonds in terms of exposure to moral hazard. The existence of a CAT bond may give an insurer the incentive to relax its underwriting and claims settlement strategies, leading to higher than expected losses. Index-linked and parametric contracts, on the other hand, are relatively free of moral hazard because they settle on industry-wide losses rather than the losses of a specific insurer.

The principal advantage of issuer-specific CAT bonds over index-linked or parametric contracts is that issuer-specific bonds have less basis risk. Recent research reveals that contracts based on state-level catastrophe loss indices expose many insurers to significant basis risk.Footnote 28 However, regional indices based on losses in sub-state geographical quadrants enable the majority of insurers to hedge very effectively using index-linked contracts. In recent periods, index-linked and parametric CAT bonds have begun to play a more important role in the market, perhaps indicating that moral hazard considerations are more important than basis risk and/or that issuers have found ways to reduce basis risk by securitizing more diversified pools of underlying exposures.