Abstract

Understanding why economies do not succeed is at least as important as understanding success. The study of failure is focused on the stability of institutions that inhibit good performance, the Northian Conundrum. Policies that seem perverse may fit into a larger institutional environment. This explains the persistence of dysfunctional institutions. The key to effective reform is to understand the underlying logic of the system. I use the phenomenon of Russian viability insurance as an example.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

3 Recently Diamond (2004) has written on the collapse of societies, focusing on environmental causes of such events. What is interesting to transition economists, however, is that in all his cases the role of ideology is paramount, leading to an inability to adapt to changes.

4 This is partly the result of Stein's law: ‘If something cannot go on for ever it will stop’. Understanding why Argentina has failed to live up to its promise is perhaps as important as determining why China has thrived.

5 Pathology is the study of sick organisms – definitely those whose self-correction mechanisms are too weak to overcome maladies.

6 This is a rather conventional way to analyse the Soviet system, as a sick economy. Alternatively, one could treat it as a different species, evolving under its own non-market logic. Different species are much more difficult to treat (reform) than sick economies. There is no drug that can turn a dinosaur into a mammal. For an evolutionary analysis of transition economics, see Ickes (2003).

7 Medical students study sick people after all. Residents work at hospitals not health clubs.

8 It may be hoped that greater comprehension provides the key to effective reform. I believe that, but I will not make that case in the present essay.

9 The Western European 12 is Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK. The Western Offshoots are Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US.

10 Galor and Moav (2005) study how increases in higher extrinsic mortality leads to an increased prevalence of somatic investment, which leads to greater health in the long run.

11 In 1950, for example, South Korean GDP per-capita was 29% of the Argentine level. Of course, South Korean performance was affected by war in 1950. However, if we look at 1913, we see that the ratio was 32% and in 1939, it was 31%. By 2000, on the other hand, it was 167%!

12 North (1991, p. 9).

13 The contrast is between internal efficiency and social efficiency.

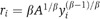

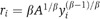

15 Output per worker in the US (in 2000) was 38 times that in Niger. If the aggregate production function is Cobb–Douglas and capital's share in output is β, then the marginal product of capital in country i is

, where y

i

is per-capita output and A is the level of TFP. Now suppose there are no institutional differences between Niger and the US, so A is identical in both countries, and let β=0.4. Then

, where y

i

is per-capita output and A is the level of TFP. Now suppose there are no institutional differences between Niger and the US, so A is identical in both countries, and let β=0.4. Then  . However, if the rate of return was so much higher in Niger, we would expect capital to flow from the US to Niger, not the other way around. This is sometimes referred to as the Lucas Paradox. See Lucas (2002, pp. 63–64).

. However, if the rate of return was so much higher in Niger, we would expect capital to flow from the US to Niger, not the other way around. This is sometimes referred to as the Lucas Paradox. See Lucas (2002, pp. 63–64).16 There is some theory to explain the dissemination of good institutions – for example, the settler mortality theory of Acemoglu et al. (2002), and the related endowments theory of Engerman and Sokoloff (1997).

17 This terminology is a bit loose. By efficient, here, I mean socially efficient, as it relates to social welfare. Alternatively, institutions can be efficient in adapting to given circumstances and resistant to change, even at the expense of social welfare.

18 Moreover, some institutions that may be socially efficient in one environment may become dysfunctional when circumstances shift. An interesting example is considered by Avner Greif (1994), in his examination of the Maghribi Traders.

19 Not the irony of using the term ‘redistributionist’ in a pejorative way, as is typical in most discussions. In fact, the market is much more redistributive. It is the non-market alternative that is protecting existing returns. The Russian Virtual Economy is the paramount example. We resort to the term redistribution because we think of the market allocation as the benchmark. However, in transition, it is really the opposite since we inherit the non-market claims to resources and rents.

20 Grossman (1983).

21 When these institutions first formed, they may have even been a socially efficient adaptation. It is the change in the economic environment that typically renders them socially inefficient.

22 Moreover, it is precisely in such periods of change that mechanisms for compensating the losers are most difficult to implement. Were this not the case there would be no need to resort to inefficient means to protect incumbents. However, if setting up compensation schemes is difficult even in normal times it is especially so when large political and economic changes are taking place.

23 When property rights are tenuous and the distribution of wealth is skewed, wealth-holders fear that redistribution (nationalisation) may take place. Hence, they will be willing to use their wealth to buy off those who might support redistribution. Gaddy and I used the metaphor of the privatization lottery to explain this in chapter 5 of Gaddy and Ickes (2002).

24 In a sense innovations are very much like economic reforms. They are both shocks that if implemented, lead to improved economic performance. However, both also have distributive impacts.

25 There was similar resistance to the germ theory of disease, first proposed by Giovanni Bonomo in 1687, yet not accepted by physicians until 1886 (Mokyr, 2002, p. 227) with the observed success of diphtheria vaccine.

26 Acemoglu (2003).

27 For our purposes, an interesting example would be oil companies. Before the oil is discovered, countries are willing to sell the rights to drill at quite favourable terms. Afterwards, nationalisation often occurs. Notice that in this case the oil company actually contributed to the creation of value, whereas rulers are much less responsible for the wealth they seek to preserve.

28 This is another way of noting that economic reforms often require a critical mass to be effective – hence, there is the problem of coordination failure. This problem is much less likely with regard to other types of innovations. I can obtain the benefits of the vaccine even if I am the only member of the family to do so. Indeed, in that case the lesson may be learned much quicker.

29 There is also the important difference that experiments with regard to a vaccine can be conducted on volunteers, with little or no side effects for the sceptical. Economic reforms can rarely be isolated in that way, as the study of Soviet partial reforms adequately taught us.

30 Gavin Wright has done important work on this. See Wright and Czelusta (2002).

31 For the latter, it is the familiar right to appropriate resources for use as inputs to continue production, and thus for managers to appropriate income streams from the enterprise's continued operations. For the former, it is protection against expropriation of profits.

32 Note that the enterprise does not have to generate a profit for the director to benefit from the income stream.

33 Gaddy and I have used the concept of market distance, d, as the state variable that describes how uncompetitive an enterprise is.

34 The example of Yukos is only too obvious here.

35 Notice that expropriation is always postponed – there is always the potential for expropriation next period.

36 See Ickes and Ryterman (1994).

37 One could also point to the growth in state control over energy resources in Russia. This is inefficient – Yukos, after all was the most efficient producer in Russia, and foreign investment and technology is likely needed for exploiting resources located in inhospitable locations. However, state control over energy provides an instrument of state power that is most powerful; an effective tool for both internal and foreign policy. Control over this instrument may be worth the sacrifice of significant future revenues.

References

Acemoglu, D . 2003: Why not a political coase theorem? Social conflict, commitment, and politics. Journal of Comparative Economics 31: 4.

Acemoglu, D, Johnson, S and Robinson, J . 2002: Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. Quarterly Journal of Economics 117: 1231–1294.

Diamond, J . 2004: Collapse: How societies choose or fail to succeed. Viking: New York.

Engerman, SL and Sokoloff, KL . 1997: Factor endowments, institutions, and differential paths of growth among new world economies: A view from economic historians of the United States. In: Haber, S (ed). How Latin America Fell Behind. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA.

Gaddy, C and Ickes, BW . 2002: Russia's virtual economy. Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC.

Galor, O and Moav, O . 2005: Natural selection and the evolution of life expectancy. Minerva Center for Economic Growth paper no. 02–05.

Greif, A . 1994: Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: A historical and theoretical reflection on collectivist and individual societies. Journal of Political Economy 102: 5.

Grossman, G . 1983: The economics of virtuous haste: A view of soviet industrialization and institutions. In: Desai, P (ed). Marxism, Central Planning, and the Soviet Economy: Economic Essays in Honor of Alexander Erlich. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Ickes, BW . 2003: Evolution and transition. In: Campos, N and Fidrmuc, J (eds). Political Economy of Transition and Development. Kluwer: Boston.

Ickes, BW and Ryterman, R . 1994: From enterprise to firm: notes for a theory of the enterprise in transition. In: Campbell, R and Brzeski, A (eds). Issues in the Transformation of Centrally Planned Economies: Essays in Honor of Gregory Grossman. Westview Press: Boulder, CO.

Kontorovich, V . 1988: Lessons of the 1965 Soviet economic reform. Soviet Studies 40(2): 308–316.

Lucas, RE . 2002: Lectures on economic growth. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

Maddison, A . 2003: The world economy: Historical statistics. OECD: Paris.

Moky, J . 2002: The gifts of Athena. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

North, D . 1991: Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Wright, G and Czelusta, J . 2002: Exorcizing the resource curse: minerals as a knowledge industry, past and present. Mimeo, Stanford University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the Association for Comparative Economic Studies, Philadelphia, PA, 8 January 2005. I am grateful to Clifford Gaddy for extensive discussions and comments on previous drafts and for allowing me to share some ideas that we are jointly working on in this address.

2 At one time, perhaps comparative economics studied alternative ways of growing rich, but today I think that is no longer the case, at least for most of us.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ickes, B. Economic Pathology and Comparative Economics: Why Economies Fail to Succeed. Comp Econ Stud 47, 503–519 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ces.8100123

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ces.8100123

, where y

i

is per-capita output and A is the level of TFP. Now suppose there are no institutional differences between Niger and the US, so A is identical in both countries, and let β=0.4. Then

, where y

i

is per-capita output and A is the level of TFP. Now suppose there are no institutional differences between Niger and the US, so A is identical in both countries, and let β=0.4. Then  . However, if the rate of return was so much higher in Niger, we would expect capital to flow from the US to Niger, not the other way around. This is sometimes referred to as the Lucas Paradox. See

. However, if the rate of return was so much higher in Niger, we would expect capital to flow from the US to Niger, not the other way around. This is sometimes referred to as the Lucas Paradox. See