Abstract

We estimate the technical efficiency of collective-owned township and village enterprises (TVEs) relative to other types of enterprise, taking into account the net work rate for equipment and machines. Our aim is to investigate whether the vaguely specified property rights of these enterprises caused them to decline in technical efficiency just before they underwent a massive privatisation programme in Wuxi City and Jiangsu province, starting in 1998. Our results cast doubt on the view that vaguely specified property rights became inconsistent with productive or technical efficiency in Wuxi City. It follows that privatisation of collective-owned TVEs may be insufficient to improve their productivity performance from now on.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

3 Dong and Putterman (1997), Pitt and Putterman (1999) and Jefferson (1999) used micro data from the same data set. If only a few data sets have been used in earlier research, it is not clear whether the data are representative of all TVEs.

4 Murakami et al. (1994), Svejnar (1990) and Pitt and Putterman (1999) also examine the allocative decision of collective-owned TVEs, but we focus on the technical efficiency, following Dong and Putterman (1997).

5 ‘Wuxi City’ refers to Wuxi Municipality in the administrative division, which is directly under Jiangsu province in the Chinese administrative hierarchy. ‘Wuxi City’ consisted of one urban area and three county-level cities during the sample period, and therefore covers a large rural area in Wuxi Municipality. Our data sample for Wuxi City consequently includes many TVEs in rural areas, although the rural area has a smaller proportion of the population engaged in agriculture and a larger proportion engaged in industry or commerce run by TVEs.

6 Basu (1996) shows that the net work rate for inputs is important in explaining procyclical productivity in the US economy.

7 In this footnote we discuss the reliability of the classification of our sample enterprises presented in the text. The classification is based on the registered ownership type of each enterprise reported in the Wuxi Statistical Yearbook for each year. It is impossible to rule out absolutely the possibility that the registered ownership types of some enterprises in our sample do not correspond to their true ownership structure, so that some enterprises registered as COTVEs, SOEs or UCOEs have already undergone property rights reform. However, we believe that this is unlikely and that the number of such enterprises is very small. In our recent field survey in Wuxi City, we have visited and interviewed about 30 enterprises from our sample, mostly privatised ex-COTVEs, and we found no misleading registrations. Furthermore, although the property rights reform of public-owned enterprises such as COTVEs, SOEs or UCOEs into SHEs, PEs or other private enterprises in Wuxi City began in 1992 or 1993, it was small-scale and experimental until the start of 1998. According to our interview with Wuxi City government, the first case of property right reform in Wuxi City was in 1992, when an SOE was selected by the central government for property right reform. From then to the end of 1997, a small number of sample firms were selected and their property rights reformed; this did not necessarily involve reducing the proportion of shares owned by government. Massive privatisation and reduction in the number of government-owned shares began in Wuxi City (and Jiangsu province) in 1998 (our interview with Wuxi City government; Zou et al., 1999). The number or ratio of SHEs and PEs in our sample before 1998 is consistent with this development of property right reform in Wuxi City (see Table 1).

8 Murakami et al. (1994) pay particular attention to cooperative enterprises in rural areas (cooperative TVEs). Our sample does not contain this type of enterprise in the rural area.

9 The data used are consequently a kind of panel data, although we do not adopt the panel estimation method in the text, for two reasons. The first is that we are not concerned with the technical efficiency of individual firms. The second is that, if we employed the ordinary panel estimation method using time-invariant firm-specific fixed effects or random effects, the average technical efficiency in each type of enterprise would be time-invariant and we could not measure the change of COTVEs' relative technical efficiency with time. In fact, to see whether the coefficients estimated using pooled data are biased, we re-estimate the production functions by panel estimation; if the results are consistent with those from pooled data, the latter must be unbiased. Appendix A therefore re-estimates production functions with firm-specific fixed effects.

10 Industry dummy variables are used to account for differences across industries. The formula allows net output to differ by industry only by shifting the intercept of the production function, not by altering factor elasticities. Since the true technologies of different industries may have distinct characteristics, our results are not definitive; further, more industry-specific studies are desirable.

11 In more detail, it is mainly in SOEs (rather than COTVEs) that higher capital-intensity in production technology has a negative influence on output or productivity, should technical inefficiency due to over-investment in capital become a serious problem for enterprises in Wuxi City. This is because SOEs tend to face softer budget constraints than COTVEs, and capital-intensity in technology is more likely to be excessive in SOEs. Moreover, if M/K (K/M), explaining variation of output or productivity, in fact measures how ‘excessive’ the capital-intensity in technology is, higher M/K (K/M) should also have greater positive (negative) influence on the output or productivity in SOEs than in COTVEs.

12 Although it would be useful to take into account the net work rate for labour, this is impossible for the following reasons. First, ln(M/K) and ln(M/L), indicating the net work rate for labour, cannot be used simultaneously in our regression model (1) since ln K, ln L, ln(M/K)=ln M–ln K, and ln(M/L)=ln M – ln L have a linear dependency. Although M/K and M/L can be used in our regression model without exact multicollinearity, this regression model has less explanatory power than that using only ln(M/K), and the estimated coefficient of M/L is not significant. Also, the regression model using only ln(M/L) as components of NWR have less explanatory power than that using only ln(M/K). Our regression model therefore uses only ln(M/K) as a variable expressing the net work rate.

13 This is equivalent to adopting a generalised method of moments (GMM) in the estimation of our regression models.

15 In 1997, PEs were clearly the most efficient of all types of enterprise, although there are only a few PEs in the samples so that reliable conclusions cannot be drawn from the results.

16 A similar fact involves the higher apparent productivity of PEs than COTVEs.

17 It has been claimed that SHEs were introduced experimentally from 1992 or 1993 (to 1997) as a reform of property rights, by privatisation of collective-owned enterprises, including COTVEs and SOEs. Based on the present estimates, however, the introduction of SHEs in Wuxi City failed to increase the efficiency of previously collective-owned enterprises (and SOEs) before 1998. Jefferson et al. (2000) also point out the poor productivity of SHEs.

18 There is further evidence that M/K reflects the net work rate more than technical inefficiency due to over-investment in capital. For representing capital-intensity in technology or potential technical inefficiency due to the adoption of excessively capital-intensive technology, K/L is a more appropriate variable than M/K (K/M). We therefore also estimate the regression model using K/L in place of ln(M/K), and also that using ln(M/K) and K/L together (in our model ln(K/L) cannot be used because of the linear dependency between ln K, ln L, and ln(K/L)). The results (not detailed here) show that the regression model using K/L in place of ln(M/K) has a much weaker explanatory power than that using ln(M/K). Also, the estimated coefficient of K/L used together with ln(M/K) in the regression model is not statistically significant, but that of ln(M/K) is significantly positive. Similar results arise for M/K (not ln(M/K)) and K/L. The observation that the capital-intensity variable K/L has a much weaker explanatory power for output or productivity than M/K indicates that the effect of M/K on output or productivity is mostly not due to the technology choice represented by K/L, but to something else such as the net work rate.

19 Dong and Putterman (2003) argue that insufficiency of working capital to finance the purchase of intermediate inputs has risen even in SOEs in the 1990s. They also found that a shortage of working capital was an immediate cause of rising labour redundancy in SOEs in the 1990s. Their argument might be extensible to the underuse of equipment and machines.

20 Based on a survey of 95 TVEs in Yi county, Hebei province in 1991, Wu (1992) reports that 83.2% of managers interviewed identified lack of funds as their most severe problem. Dong and Putterman (1997) show in a study of 89 rural enterprises in China (collective-owned TVEs and private enterprises) that their credit was indeed constrained, and that access to credit improved the productivity of these enterprises.

21 Pan et al. (1997) and Zou et al. (1999) point out that, because of the vague property rights of COTVEs, their property was poorly managed. For example, ground rent or other rents were often not collected (Zou et al., 1999). Shi (1997) argues that township and village governments in China arbitrarily levied expenses for social welfare on COTVEs, because these governments effectively constituted the management of the COTVEs. This was a burden, even though productivity was not directly harmed. Privatisation removes these problems.

References

Alchian, A and Demsetz, H . 1972: Production, information cost and economic organization. American Economic Review 62: 777–795.

Basu, S . 1996: Procyclical productivity: Increasing returns or cyclical utilization? Quarterly Journal of Economics 111: 719–751.

Chang, C and Wang, Y . 1994: The nature of the township–village enterprise. Journal of Comparative Economics 19: 434–452.

Che, J and Qian, Y . 1998a: Insecure property rights and government ownership of firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics 113: 467–476.

Che, J and Qian, Y . 1998b: Institutional environment, community government, and corporate governance: Understanding China's township–village enterprises. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 14: 1–23.

Chow, KWC and Fung, MKY . 1998: Ownership structure, lending bias, and liquidity constraints: evidence from Shanghai's manufacturing sector. Journal of Comparative Economics 26: 301–316.

Dong, X-Y and Putterman, L . 1997: Productivity and organization in China's rural industries: a stochastic frontier analysis. Journal of Comparative Economics 24: 181–201.

Dong, X-Y and Putterman, L . 2003: Soft budget constraints, social burdens, and labor redundancy in China's state industry. Journal of Comparative Economics 31: 110–133.

Hsiao, C, Nugent, J, Perrigne, I and Qiu, J . 1998: Share versus residual contracts: The case of Chinese TVEs. Journal of Comparative Economics 26: 317–337.

Jefferson, GH . 1999: Are China's rural enterprises outperforming state enterprises? Estimating the pure ownership effect. In: Jefferson, GH and Singh, I (eds). Enterprise Reform in China: Ownership, Transition, and Performance. Oxford University Press: New York, pp. 153–170.

Jefferson, GH, Rawski, TG, Wang, L and Zheng, Y . 2000: Ownership, productivity change, and financial performance in Chinese industry. Journal of Comparative Economics 28: 786–813.

Jiang, C . 2000: Fund resources of township–village enterprises and dynamic change in their financing structure: Analysis and consideration (xiangzhenqiye zijinlaiyuan yu rongzijiegoude dongtaibianhua: fenxi yu sikao). Economic Research Journal (jingji yanjiu) 2: 34–39. (in Chinese).

Jiang, G . 2000: Combination of production operation and capital operation as a way of revitalizing township–village enterprises (shengchan jingying ziben jingying yu xiangzhenqiyede ‘ercichuangye’). Chinese Rural Economy (zhongguo nongcunjingji) 3: 50–55, (in Chinese).

Kornai, J . 1980: Economics of shortage. North-Holland: Amsterdam.

Li, DD . 1996: A theory of ambiguous property rights in transition economies: The case of the Chinese non-state sector. Journal of Comparative Economics 23: 1–19.

Li, J and Yan, B . 1998: The development patterns of township–village enterprise (xiangzhenqiye fazhan moshi). In: Li, J and Yan, B (eds). Economic Report of China (zhongguo jingji wenti baogao), Economic Daily-Verlag (jingji ribao chubanshe): Beijing, China. pp. 647–665. (in Chinese).

Lu, W . 1999: Agro-economic situation in 1998 and prospects for 1999 (1998 nian nongyexingshi yu 1999 nian zhanwang). In: Ma, G and Wang, M (eds). 1998–1999 Economic Situation and Prospect of China (1998–1999 zhongguo jingjixingshi yu zhanwang). Zhongguofazhan - Verlag (zhongguo fazhan chubanshe): Beijing, China. pp. 19–29. (in Chinese).

Murakami, N, Liu, D and Otsuka, K . 1994: Technical and allocative efficiency among socialist enterprises; the case of the garment industry in China. Journal of Comparative Economics 19: 410–433.

Pan, C, He, L and Zhuang, Y . 1997: Research on the condition of establishment of collective owned economic structure in our province (wosheng xiangcun jiti jingji zuzhi jianshe zhuangkuang diaocha). Jiangsu Rural Economy (jiangsu nongcun jingji) 7: 13–15. (in Chinese).

Pesaran, MH and Smith, RJ . 1994: A generalized R 2 criterion for regression models estimated by the instrumental variables method. Econometrica 62: 705–710.

Pitt, MM and Putterman, L . 1999: Employment and wage in township, village, and other rural enterprises. In: Jefferson, GH and Singh, I (eds). Enterprise Reform in China: Ownership, Transition, and Performance. Oxford University Press: New York. pp. 197–215.

Shi, X . 1997: Local governments' withdrawing from micro economic agents: A choice across centuries (shequ zhengfu ‘tuichu’ weiguan zhuti -sunan xiangzhenqiye shiji zhi jiao de xuanze-). Jiangnan Review (Jiangnan luntan) 2: 29–30. (in Chinese).

Svejnar, J . 1990: Productive efficiency and employment. In: Byrd, W and Lin, Q (eds). China's Rural Industry: Structure, Development, and Reform. Oxford University Press: New York. pp. 243–254.

Weitzman, M and Xu, C . 1994: Chinese township–village enterprises as vaguely defined cooperatives. Journal of Comparative Economics 18: 121–145.

Wu, J . 1992: The new features and problems of township and village enterprises in low income areas. Economic Management Research 4: 58–61.

Xu, Z and Zhang, J . 1997: Rapid expansion of fund of township enterprises and decline in the returns–a positive study into township enterprises in Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province (xiangzhenqiye zijinde gaosuzengzhang yu xiaoyi xiahua – jiangsusheng suzhoushi xiangzhenqiye shizhengfenxi). Chinese Rural Economy (zhongguo nongcunjingji) 1: 51–58. (in Chinese).

Yang, Q . 1997: Main contradiction and its solution to continued economic growth in China (woguo jingji shixian chixu zengzhang mianlin de zhuyao maodun yu duice fenxi). China Industrial Economy (zhongguo gongye jingji) 8: 5–9 (in Chinese).

Zou, Y, Dai, L and Sun, J . 1999: A study of township and village enterprises reform in Southern Jiangsu province (sunan xiangzhenqiye gaizhi de sikao). Economic Research Journal (jingji yanjiu) 3: 59–65 (in Chinese).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

We thank Akira Kosaka, Hiromi Yamamoto, Hiroshi Ohnishi, Yukihiko Kiyokawa, Deqiang Liu, Naoki Murakami and anonymous referees for helpful comments. All views and any errors are the authors'.

2 Even collective-owned independent TVEs had higher efficiency levels than state-owned enterprises and urban collective enterprises at their final estimates.

Appendices

Appendix A: Estimation results by production functions with firm-specific fixed effects

As stated in footnote 9, in order to find out whether our estimates of coefficients are biased, we now re-estimate the production function using the panel estimation method. If the resulting estimates are consistent with those in the text, the latter are unbiased.

Here, we estimate the production functions with firm-specific fixed effects using the same micro data as in the test:

and

where c i is the firm-specific fixed effect of firm i and the other notation is as in the text. A random effects model cannot be adopted since in every case the Hausman–Wu test rejects the null hypothesis that the model specification of production function with firm-specific random effects is valid.

The estimation procedure for the production functions (A.1–A.3) is the same as in the text: simultaneous estimation of each production function with equation (4) in the text, and the regression equations of ln K and ln L to instrumental variables by the 3SLS method, taking heteroscedasticity into account.

The estimates of production functions (A.1–A.3) are presented in Table A1. For ease of comparison, estimates of the production function without NWR and with firm-specific fixed effects are also reported in Table A1.

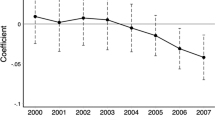

The estimates in Table A1 indicate that, using production functions with firm-specific fixed effects, we obtain similar estimates of coefficients as in the text for all important purposes. The estimated coefficient of time dummy variables tends to increase. Between COTVEs and PEs and the other types of enterprise group, there is likely to be a difference in the influences of ln(M/K) on the output or productivity, and the estimated coefficient of ln(M/K) × time dummies also tends to increase year by year. Also, there are no large differences between Tables A1 and A2 in the estimated elasticity of output to capital (K) and labour (L).

To measure the differences between the average technical efficiencies of COTVEs and other types of enterprise, the estimates of firm-specific fixed effects obtained in the estimation of production functions (A.1–A.3) were regressed to enterprise-type dummy variables and industry dummy variables. The industry dummy variables are expected to account for the differences in production technologies between industries. The results are shown in Table A2.

In Table A2, the estimated coefficients of the dummy variables for SOEs, SHEs, JVs, UCOEs, UCEs are significantly negative, whereas that of the dummy variable for PEs is never statistically significant. This result indicates that the average technical efficiency of COTVEs has been higher even than that of JVs and SHEs, as well as SOEs, UCOEs and UCEs in the 1990s. This is consistent with the estimates in the text.

It is reasonable to conclude from these results that the estimates of the coefficients in the text are not seriously biased.

Appendix B: Data construction

In constructing the data used for making estimates, the following deflating methods have been used for output and inputs.

deflating method for output

Output is measured by the net output (added value) at 1991 fixed prices, that is,

where t is the time index, j is the industry index, GV is the gross value of output at current prices, PME represents intermediate inputs at current prices, DEFO is the deflator for output and DEFI is the deflator for intermediate inputs. As indicated above, different deflators are used for the gross value of output and for intermediate inputs; this is called double-deflation. The aim is to avoid biased measurement of real net output arising from differing inflation rates between the final product and intermediate inputs. The price deflator for output is defined as

where GV90 is the gross value of output at 1990 fixed prices.

Deflating method for intermediate inputs

The intermediate inputs variable (M) is measured by intermediate inputs at 1991 fixed prices (PME t /DEFI jt ).

The price deflator DEFI for intermediate inputs is derived from the data on ‘the purchase price index of materials, coals, and engines’ and the deflator for ‘the services price indices’ published in the Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook. The DEFI is derived as a weighted average price index. The weights are the average share of each component in the sum of the value of current intermediate inputs for each industry in the sample. The value of the intermediate inputs for each industry are obtained from the input–output table for China for 1992, 1995 and 1997, published in the China Statistical Yearbook. The shares of intermediate inputs for 1991 and 1992 are based on the input–output table for China for 1992; the shares of intermediate inputs for 1993, 1994 and 1995 are based on the input–output table for China for 1995; and the shares of intermediate inputs for 1996 and 1997 are based on the input–output table for China for 1997.

The price deflator was normalised by taking the 1991 index as 100%.

Deflating method for fixed assets

Capital is measured by the real original value of fixed assets. The price deflator for fixed assets is derived from ‘the price indices of investment in fixed assets’ of Jiangsu province in the Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook. This item is divided into three components: ‘construction and installation’, ‘purchase of equipment, tools, and instruments’ and ‘other’. The deflator for fixed assets is derived as a weighted average price index. The weights are the average share of three of each component in the total investment in fixed assets. The weight of each component in the investment differs now not only for each industry but also for each type of enterprise. For example, SOEs have a larger construction share in their fixed assets than other enterprises; this includes more nonproductive resources, such as housing, schools, health facilities and other services for industrial workers and their families. Our procedure therefore includes separate calculations for SOEs, TVEs (including COTVEs) and other types of enterprise, although the Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook did not give data showing the allocation of investment by SOEs, TVEs and other types of enterprise. This Yearbook divides the investment in fixed assets into four types: investment in capital construction, in innovation, in urban collective units and in rural areas. Here, since investments in capital construction and innovation appear to be mainly for use by SOEs, we have assigned the shares of the three relevant components to the sum of investments in capital construction and innovation for SOEs. The share of investment in rural areas is assigned to TVEs, and the share of investment in urban collectives is assigned to the other types of enterprises.

As stated above, capital is derived from the deflated original value of fixed assets, taking the 1991 index as the price base. The figures are as follows:

where s denotes the rate of physical depreciation of fixed assets in every year, assumed to be 3%, m is the index denoting enterprise type, OF is the nominal value of the original value of fixed assets, DOF is the deflated original value of fixed assets and DEFA is the deflator for the original value of fixed assets.

Finally, labour is taken as the total number of year-end employees.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yano, G., Shiraishi, M. Efficiency of Chinese Township and Village Enterprises and Property Rights in the 1990s: Case Study of Wuxi. Comp Econ Stud 46, 311–340 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ces.8100037

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ces.8100037