Abstract

This paper assesses empirically the electoral impact of an immensely popular Vote Advice Application and TV show (‘Do the Vote Test’) during the 2004 Belgian election campaign. Vote Advice Applications are becoming more popular in several Western countries and ever more voters get a voting advice during an election campaign. Drawing on a large panel of Internet users, the study systematically compares users and non-users of this Vote Advice Application, testing whether getting a personal vote advice made any difference. We find that ‘Do the Vote Test’ indeed has affected Belgian voters’ final decision but at the same time these effects were modest. Some parties gained some votes due to the ‘Do the Vote Test’, and others lost some votes, but probably the application did not strongly affect the overall election outcomes. Finally, we show that people's subjective perceptions of the impact of ‘Do the Vote Test’ on their actual electoral behaviour are often contradictory.

Similar content being viewed by others

The study examines the electoral effects of a non-partisan Vote Advice Application or party profile website in Belgium.Footnote 1 , Footnote 2 Vote Advice Applications have become increasingly popular in many European countries during the last few years. Media companies or independent agencies, not connected to the competing parties, have set up popular websites, giving voters advice about which party programmes come closest to one's own preferences. In some countries, the websites have been launched via major TV shows, giving viewers the chance to participate and to receive their interactive voting advice immediately while watching TV. Both the websites and the TV shows have often had impressive participation rates and viewing figures. A great many people have been exposed to their personal voting advice. Set up by non-party actors during the campaign, we want to gauge these voting advice applications’ electoral consequences. Although these applications are not explicitly aimed at influencing the election outcome, their advices may have that effect.

Are these applications really affecting people's choices in the ballot? Or are they, in contrast, nothing but entertainment without any tangible electoral consequences? These questions are important. In some of the countries with popular voting advice applications, a vivid debate ensued about the acceptability of voting advice applications. Some maintained that voting advice applications are a fraud that would never be able to give a correct and neutral voting advice; others contended that these applications must be commended as they focus peoples’ attention on party programmes and on policy issues, thereby compelling parties to discuss substance instead of personalities, images and campaign events.

Belgium is one of those European countries in which voting advice applications have boomed during the last few elections. Modestly starting in 1999, the last two national campaigns of 2003 and 2004 witnessed a major breakthrough. Especially the public TV broadcaster VRT has engaged itself in voting advice applications via the Internet and it has broadcasted very popular TV shows called the ‘Do the Vote Test’, launching their voting advice web application in 2003 as well as in 2004. Taking Belgium (Flanders) as an example, it is the effect of this very popular ‘Do the Vote Test’ TV-show annex web application that will be scrutinized in this study.Footnote 3 Just like in other countries, the discussion about the acceptability of this initiative has been very lively.Footnote 4 In order to investigate whether the ‘Do the Vote Test’ really made a difference in Belgium (Flanders) in 2004, we will draw on a large but non-representative panel of 7,500 voters.

First, the paper briefly sketches what voting advice applications are and documents their rising popularity. Second, we explain the relevance of voting advice applications in terms of their potential impact on voting decisions. We link voting advice applications with the idea of issue voting and explain that the rise of voting advice applications may significantly affect peoples’ tendency to vote because of issues. Next, we describe the Belgian public broadcasters’ ‘Do the Vote Test’ in more detail and show that the potential electoral impact of this application was considerable. Then, we empirically test whether we find any electoral effects by systematically comparing participants and viewers of the ‘Do the Vote Test’ with non-participants and non-viewers. We end with a conclusion and discussion section.

Voting advice applications online and on TV

All Voting Advice Applications (from now on: VAAs) work according to a comparable logic. Participants answer a series of questions about their political preferences on a special website. The application contains (weighed) information about parties’ programmatic stances. Drawing on this information, the VAA calculates which parties’ electoral offer comes closest to the participant's preferences and supplies the participant with a list of parties in decreasing order of congruence with his opinions and beliefs (see also Teepe, 2005). As such, most VAAs do not literally ‘advice’ someone to vote for a certain party, but they link someone's opinions to official party stances and, at least, contain an implicit voting advice. Although all VAAs work more or less similarly, there are some important variations in the way the closeness to the party is measured — via very concrete policy measures or via more general ideological statements — and how the advice is presented to the user — as a mere list of parties or as a plotted individual position in a multidimensional party space (for more information on these modalities, see Teepe, 2005; Kleijnnijenhuis and Krouwel, 2007; Van Praag, 2007). These differences in preference measurement and advice ‘format’ may affect the way VAAs impact the vote.

In many countries, we are witnessing a fast rise of VAAs. An expert survey among European political scientists showed that already in 15 European countries there has been a VAA.Footnote 5 It concerns mostly Central (e.g. the Netherlands, Germany) and North European (e.g. Finland, Sweden) countries. In Eastern-Europe, VAAs are not yet that popular although there are some exceptions (Czech Republic, Hungary). The presence of a VAA seems to be associated with multi-party systems (Hooghe and Teepe, 2007) and an independent media system (Walgrave et al., 2008).

The Netherlands has doubtlessly been the VAA pioneer, with the first print-based application in 1989. In 1998, the Stemwijzer went online for the first time, giving 250,000 voters advice. Note that we do not know whether these are unique advices or repeated advices given to the same participant. This figure exploded to 4.7 million advices given in 2006 or an astonishing 40% of the Dutch electorate. Furthermore, 1.5 million voters also used Kiescompas, another popular VAA in the Netherlands (Kleinnijenhuis et al., 2007). Finland is another early adopter, with the first and still most popular VAA starting as early as in 1995. Four years later, the Fins already had four television channels, each of them broadcasting a very popular television show presenting a different VAA. Just as in the Netherlands, in Finland, voting advice has become a natural part of the campaign.

At the beginning of the new century, the successful Dutch Stemwijzer was exported to several other countries. In 2002, the German Wahl-o-mat was fielded for the first time and it has attracted more than 10 million users since. In Switzerland, both Politarena and Smartvote started in 2003, reaching 600,000 people. Since then, more than 20 different vote applications were designed for several local and national elections. Besides Switzerland and Germany, Belgium (Flanders) has also been inspired by the Dutch example. In 2003 and 2004, the Flemish public broadcaster VRT launched its ‘Do the Vote Test’ TV-show annex, VAA which rendered 840,000 advices in 2004 (Walgrave and Van Aelst, 2005). Together with the success of the VAA of the daily De Standaard, this amounted to about 1,000,000 VAA advices in 2004 in Flanders.Footnote 6

VAAs and Issue Voting

Why are VAAs relevant for political scientists? The straightforward answer is that VAAs may influence the voting behaviour of citizens. While the traditional ties between voters and parties have dissipated and voters have become less loyal (Dalton and Wattenberg, 2000), at least the potential impact of VAAs has risen. Voters are floating and seeking clues to know which party is ‘their party’. VAAs take voters by hand and guide them through a complicated political landscape. They do so on the basis of issue stances and could therefore enhance the so-called ‘issue-voting’. Issue voting refers to behaviour: citizens basing their vote on a perceived proximity between their own position on an issue (e.g. in favour or against capital punishment) and the party they vote for (Downs, 1957). Although there are different conceptions of issue voting (MacDonald et al., 1991), issue voting basically means that people vote for a party because of its policy proposals. Whether voters can take into account many different party positions at the same time or tend to base their vote on only a handful of issues is still open to debate (Maddens, 1994). The electoral literature contends that issue voting is only one of the possible reasons underlying people's vote. People may also vote out of ideological reasons, to defend their group's interest (e.g. class voting), because they like an individual candidate, to punish elite parties, etc. Some say issue voting is increasing as a motivator of electoral choice, and others doubt that this is the case (Aardal and Van Wijnen, 2005). Either way, a key aspect of issue voting is information: people need to be informed about what positions parties have adopted regarding the issues they care about. If people are not informed about a party's or a candidate's position, if they are uncertain about political actors’ issue position, they have difficulties basing their vote on their own issue preference (Bartels, 1986). Many voters do not have the time or the willingness to inform themselves about parties’ positions. Especially people with a low level of political interest are most of the time only weakly informed about what parties stand for (Goren, 1997). They use cognitive shortcuts to derive parties’ positions or they base their choice on other reasons that are hardly or not connected to parties’ preferences (see above). Indeed, it is not so easy for voters to compare parties’ issue positions. There are several reasons for this. First, to the extent that a party system consists of several parties, it becomes more difficult for voters to compare all these parties’ positions, certainly when some of these parties are less visible in the media and hardly get the opportunity to present their stances to the public. Second, some issues, maybe the issues a particular voter cares about, are underexposed in the media, which makes the task of getting the knowledge about what parties think about it almost impossible. Moreover, parties often tend not to be very precise in laying out their policy preferences. When parties have preferences they consider to be unpopular, or when they think other parties are considered by the public at large as ‘owners’ of the issue, they will try to avoid playing an open card and remain quiet about the issue and their position on it. It is one of the main findings of the electoral literature that parties, during the campaign, tend to talk next to each other, not reacting to each other's issue positions. Hence, people, normally, would only be informed about certain parties’ positions on certain issues, while for other issues they would know the ideas of yet other parties. This makes comparing parties’ issue positions and, thus, issue voting cognitively difficult.

This is where VAAs come in. A VAA may dramatically reduce the information costs for voters who want to base their vote on a comparative assessment of the competing parties’ policy preferences. Especially among the less politically interested for whom the information costs may be too huge a price, VAAs may spur issue voting. They take the burden of informing themselves out of the voters’ hands and deliver concise, easy to interpret and readily digestible information. Consider what VAAs typically do: they give an ‘objective’ advice by comparing many issues for many parties drawing upon straightforward statements. Moreover, the VAAs force parties to play open cards and to publicize their preferences, even if these preferences are not popular. Instead of coming with a price, VAAs may make issue voting much easier.

If this is true, we would expect that VAAs, in the long run, would change voting behaviour. Issue voting might become more widespread as its information burden goes down. The fact that VAAs seem to be popular, especially in countries with a large and fragmented, and thus complicated, party system, indicates that information is key. VAAs may not only change voters’ behaviour, they may also change the way in which parties conduct their campaigns. The VAA itself may become one of the campaign highlights or one of the primary targets of parties’ campaigns. In some countries, VAAs have become the subject of an intense debate and even a controversy, which proves that VAAs are taken seriously by political parties. We believe VAAs must be taken seriously by political scientists too.

‘Do the Vote Test’ in Belgium

In late 2002, the Belgian public TV broadcaster VRT decided to make its own VAA and to produce a major Sunday evening TV show to launch it at the start of the electoral campaign 6 weeks before the ballot on 18 May 2003. Inspired by the Dutch TV show Waar Stem ik op?, aired on the commercial channel SBS6 a year earlier, the VRT asked two Belgian universities to devise a new VAA called ‘Do the Vote Test’ (DVT). The TV show was broadcasted on 20 April 2003. This inspired the VRT to repeat the same exercise for the regional elections on 13 June 2004. This time, VRT played it even bigger. They broadcasted three Sunday evening-filling TV shows dedicated to stances of parties and voters regarding money, quality of life and value issues. For each show a separate voting advice was given. The final show was aired a week before the ballot. The shows were able to attract a large audience: the absolute viewing figures (+12 year) lay between 10 and 14% with a market share of 51–63%. On average, 640,000 Belgians watched the three TV shows. While watching TV, people could participate via the Internet, mobile phone and landline phone. At the end of each of the three programmes, they would get their personal voting advice. The website containing the VAA was immensely popular; it gave 840,000 advices in the 4 weeks preceding Election Day.

We do not dispose of information about the socio-demographics of the DVT users. Yet, we think it is safe to assume that they display the profile that is typical for the interested and politically active citizen. This was confirmed by a study of Hooghe and Teepe (2007), who analysed the log files of the users of the VAA Wij Kiezen Partij voor U from the daily De Standaard in 2003 and 2004 and found that the typical user was young, male and highly educated. There are no reasons to expect that DVT users would be different. Maybe the somewhat more popular profile of the public broadcaster VRT compared to the rather elitist public of the broadsheet De Standaard might have made a (small) difference.

DVT was controversial, both in its TV format and in its Internet application. Especially the opposition parties accused the VRT of fuelling populism and simplifying politics into all-too-easy yes/no statements. The public broadcaster ran all its 2004 election programmes under the baseline ‘The VRT helps you to vote’. This was clearly picked up by the parties as they all considered DVT as being extremely important and as a major campaign event. Programme-makers were invited in parties’ headquarters to defend their approach and to convince party leaders to participate in the TV show and the VAA. A recent surveyFootnote 7 among Flemish politicians confirmed the huge importance they attributed to ‘Do the Vote Test’. More than half of the MPs agreed with the statement that ‘TV-shows like “Do the Vote Test” have considerable impact on people's voting behaviour’, and only 17% disagreed.

Thus, the high viewing and participation rates, the political controversy surrounding DVT and the high impact that politicians attribute to it all suggest that DVT may have had a huge electoral impact on the Belgian electorate in 2004.

Data and Methods

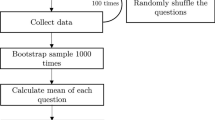

We draw upon the University of Antwerp Web-based Electoral Panel 2004 (UAWEP-2004). This is a five-wave, non-representative pre- and post-electoral panel of 11,486 voters in Belgium (Flanders) in March–June 2004. The panel was devised with five consecutive waves: two pre-campaign waves (W1 and W2), two campaign waves (W3 and W4) and one post-electoral wave (W5).

Although also within academia gradually more web-based surveys are being conducted (Dillman, 2000; Best and Krueger, 2004), most web-panels are set up for commercial reasons and it certainly is not a common research technique for electoral surveying yet. The main problem with web surveys is, of course, representativity. The strategy we followed to circumvent this problem for the present study was very simple: we tried to maximize diversity. We reconciled ourselves from the beginning to the fact that our study would not be able to get a true random sample of the Belgian (Flemish) population. Self-selection is too huge a problem, as we could only ask people to participate but could not control in any way for non-participants or for people who were not reached by us. We tried to put together a panel that was as diverse as possible and that drew respondents from all corners of society and from all walks of life. For this purpose, we recruited panel participants via banners on websites of popular radio stations, of soccer teams, of associations of the elderly, of women's organizations… Students, taking a class in methods, distributed leaflets inviting people to participate at train stations, on the streets, in bars… We also relied on snowball sampling, asking participants to invite other people they knew. Additionally, via email we recontacted all participants (N=3,500) who participated in an electoral panel set up for the previous 2003 elections.

Table 1 contains the response rates. They go down gradually. Sometimes, respondents decided not to participate in, for example, wave 3 but then they remained on board and participated again in wave 4 and/or 5. The panel was substantially skewed; we will come back to that shortly, but the dropout from W1 till W5 did not really worsen its substantial initial skewedness. For example, dropouts came from all political leanings, were not less educated, not more female than male, etc.

Our design has advantages and drawbacks. The main drawback is that we do not dispose of representative data for the Belgian population. Our main goal, however, is not to put forward definitive statements about the Belgian population and its electorally floating behaviour in 2004. Rather, we want to explore whether DVT may have made a difference. The main question is whether we have enough diversity and variation in our sample to test for relationships and effects between variables. In what respect is our sample most skewed? Comparing our panel participants with the population at large, three features catch the eye: our participants are younger, they are more educated and they have more interest in politics than the average Belgian. These biases are linked to two characteristics of the sampling procedure: students and university teachers mobilized in their respective social environments; people were mainly contacted via electronic media. The available data on Internet use confirm that, in Belgium, Internet use is still concentrated in the younger and affluent segments. Because we do not want to create the impression that our data are representative, and because of unwanted effects of weighing procedures, we will not weigh our data (Table 2).

The main strength of the study is that the number of respondents is high. The UAWEP-2004 contains 7,413 usable respondents, who answered at least one pre-campaign (W1 or W2) and the post-electoral wave. Moreover, we dispose for a large number of voters per party; for all major parties we have at least 1,000 respondents in our database.

A second strength is the fact that due to the panel design, we could avoid working with questionable recall data. Most of the research into electoral campaign effects is based on cross-sectional post-electoral surveys (Schoen, 2000). After an election, people are asked about their electoral behaviour in the previous election and the elections before that. Sometimes, these post-electoral surveys take place months after the actual elections, which reduces the reliability of the answers considerably. Recall questions tend to overrate the consistency of voters (Schuman and Presser, 1981; Schoen, 2000). As we will show, people's answers are often unreliable or, at least, inconsistent. What people afterwards say they did and what they actually did was often different. Only panel studies, tapping electoral preference several times during the campaign, are fit to gauge intra-campaign change and that is what we are after here.

In terms of DVT, we questioned our panellists just before the first DVT TV show and the launch of the VAA in wave 2 (W2) and right after the DVT programmes in wave 4 (W4). This design allows us to make a reasonable estimate of the effect of DVT on our panellists’ electoral intentions. In wave 4 (W4), we additionally posed some very specific questions about ‘Do the Vote Test’. Firstly, we asked whether people had watched one or more of the three DVT TV shows. Secondly, we asked whether they also used the VAA (via Internet or mobile phone) to get a voting advice. Finally, we also asked them whether they thought DVT had affected their electoral preferences.Footnote 8

What can we learn about DVT's effects on the Belgian electorate from our panel? As mentioned above, our panellists are not representative for the population at large. They are Internet users displaying specific characteristics. Yet, the effects of DVT apply especially to people with Internet since the large majority of DVT users got their voting advice via the Internet (in contrast to via cell phones, etc.). Hence, if DVT affected the population at large, we should certainly find some traces of that among our panellists. Indeed, the surveyed people are younger, more educated and, especially, more interested in politics than the average citizen. Consequently, they had been exposed to DVT to a much larger extent than the population at large. While, as mentioned above, ‘only’ 10–14% of the Belgian population watched the DVT TV shows, in our panel no less than 64% said that they watched at least one of the three shows. Without counting the double users, we estimate that DVT gave voting advices to about 500,000 Belgians, which is 8% of the Belgian (Flemish) population. Among our panellists, in contrast, no less than 54% said that they got a voting advice from DVT. This indicates that, in our panel, we can compare two almost equal groups of users (exposed group) and non-users (control group).

Analysis and Results

DVT's electoral influence according to voters

We asked our panellists in wave 5, after Election Day, whether VAAs like DVT had an impact on their vote. In sharp contrast to the opinions of politicians and journalists about DVT's electoral power, an overwhelming majority denied that DVT had affected their electoral preference. Table 3 contains the answers of only the people who used DVT or watched the TV show.Footnote 9

More than 90% of our panellists who watched the TV show or got a personal voting advice denied that DVT affected their vote: they did not bother about the voting advice or their existing preference was confirmed. This suggests that a huge amount of voters sought in the first place a confirmation of their preference and did not want to be challenged by DVT. Only one in 10 users said that DVT contributed to their doubt and barely one in a hundred said that DVT made them change their mind.

We not only asked our panellists an explicit question about the impact of DVT on their vote, we also confronted them in wave 5 with a list of possible information channels that had been important in making their choice. In this list, an item on VAAs was also included: ‘the results of VAAs on the Internet or on television’. VAAs were not an important information channel according to most voters. VAAs only occupied the 6th place of information channels, with only 5% of people stating that VAAs had been important. TV debates, discussions with friends, coverage in newspapers, information on the Internet and direct partisan information, as our panellists stated, are all more important than VAA results. Yet, the opinion of the associations that the respondents were members of, opinion polls, and posters had been even less important than VAA results. Note, again, that our panellists had been much more confronted with DVT than the average Belgian.

Table 3 contains the results split up per party. As mentioned above, DVT was not the only VAA that was available during the 2004 campaign. Also, the VAA produced for the newspaper De Standaard was very popular and yielded many advices. The survey question, thus, not only tapped DVT's effect but also the effects of VAAs in general. We do not dispose of evidence regarding the party advices given by DVT but the log files of the De Standaard VAA have been analysed by Hooghe and Teepe (2007). They showed that the VAA of De Standaard delivered a massive amount of voting advices to vote for Sp.a–Spirit and a relatively small amount of advices to vote for Groen!. This bias might have affected the figures in Table 3. Subjectively least affected by VAAs was the extreme-right Vlaams BelangFootnote 10 voter, followed by the CD&V–N-VA electorate. Subjectively most affected by VAA advices were the voters of the liberal cartel VLD–Vivant.

Both measures grasping subjective beliefs of voters about what had affected their vote must be interpreted with caution. People might deliberately deny the impact of a VAA like DVT because this might indicate political immaturity. The impact of DVT could have been unconscious; one could have forgotten that DVT played a role. Moreover, the impact VAAs have on voters might be indirect, not directly affecting voters’ actual voting behaviour but rather steering their attention towards parties and influencing the ‘acceptability’ of parties. We will come back to this in the conclusion. For all these reasons, we do not only need evidence of what people say about DVT but also what they actually did after having watched or used DVT. The following sections present this harder evidence.

Did DVT make voters change their minds?

In Belgium, like in many other countries, electoral volatility is on the rise. Voters switch parties more often than they used to. This not only happens between elections but also within an election campaign. In the 1980s, only 15% of the voters changed parties between elections (Swyngedouw et al., 1992); this turnover rate grew to around one third of the electorate by the end of the 1990s. The national election survey showed that 24% of the Belgians switched allegiances in 2004 compared to the 2003 national elections organized hardly a year earlier (Goeminne and Swyngedouw, 2007). Can DVT be held responsible?

On an aggregate level, we do not find any trace of a rising number of party switchers in the period that the DVT TV shows were broadcasted or that the VAA was online in May 2004. In all periods from the start of the panel in March 2004 onwards, the number of switchers roughly equalled 10% of the panellists and this figure was not higher in May 2004. On an individual level, we asked our panellists in wave 2 (April), before DVT started, to inform us about their voting intentions. We asked them the same question again after DVT (June) and after the elections (end of June). This allows us to check whether viewers and users of DVT switched more between parties than non-viewers and non-users. If DVT made people change their minds, we would expect that the exposed group shifted party allegiance more often. Table 4 shows that this was not the case.

The first two columns of the table show that differences in vote intention changes across exposure conditions are minimal. Although we observe that watching+using translates into a slighter higher change rate between W2 and W4 (16%) than not watching+not using (14%), no changes W2 → W4 (column 1) are significant: people who watched/used DVT did not significantly change party preference more often than those who did not watch/use DVT. Regarding changes between W2 and W5, column 2 shows that DVT users/watchers switched parties even less. Hence, if DVT might have slightly affected their voting intention between W2 and W4, in W5 they returned to their old party; voters not exposed at all (not watching+not using) even changed parties most often (19%).

A closer look at the table shows that watching or not watching hardly had any effect. If there is a DVT effect, it arises from participating and from getting a personal voting advice. This is shown in column 3. Comparing W2 and W4, users, indeed, switch more than non-users (16 vs 13%) and this difference is significant. Therefore, in what follows, we will concentrate on comparing users with non-users and neglect the fact as to whether people watched the DVT TV show(s) or not. This finding confirms the hybrid character of the DVT event: on the one hand, it was a night-filling and entertaining political TV show seemingly without any effects but, on the other, it was an interactive VAA that may have had electoral consequences. We estimated a multivariate model (logistic regression) that, controlling for the traditional socio-demographic factors of age, sex and education, predicted party change between W2 and W4. Having used DVT was a significant predictor of party change but it had only a very small effect (R 2=0.009). Looking further, DVT participation's changing effect completely disappeared by Election Day (W5) as column 4 shows. DVT use seems only to have affected vote intention but not the actual vote behaviour: groups, users and non-users display an almost identical volatility on Election Day. Hence, if there has been an effect, it has been temporary.

Talking about the ‘effects’ of DVT participation implies a causal relationship: without participating in DVT people would not have changed parties. But exactly the reverse could also be true: people still in doubt about their vote were searching for information about parties’ stances; they used DVT to supply that information. The data, however, do not support this alternative interpretation: undecided voters did not use DVT to a larger extent than voters who had made their mind up yet. This suggests that some people use VAAs like DVT to confirm or test their existing preference and not to be convinced to vote for another party. People do not turn to VAAs because they do not know but because they want to check whether the VAA gives them the ‘right’ advice.

We can conclude that only watching the DVT TV show(s) had no effect on party change among our panellists. Actually using the interactive vote advice application to get a personal advice seems to have had a significant but limited effect. The effect completely disappeared by the time people had to vote for real. Many people sought a confirmation of their (firm) party preference instead of desperately seeking for an advice because of doubts. All these intermediary conclusions, however, do not tell us anything about the different political parties and whether and how their electoral fate may have been affected by DVT.

Winners and losers of DVT?

A part of the controversy about DVT in Belgium was related to the fact that the major parties formed cartels with minor electoral partners in 2003 and 2004. In 2003, the socialist party Sp.a went to the ballots together with Spirit, a small left-liberal party. In 2004, the right-liberal VLD forged a union with the tiny Vivant party while the Christian democrats of CD&V went together with N-VA, a small Flemish nationalist formation. The reason for this sudden boost in electoral carteling was simple: the installation of a new electoral threshold of 5%. But the cartel partners, forming an electoral alliance and presenting one list to the voters, maintained their separate programmes and did not present themselves with a common electoral platform. Consequently, the DVT developers decided to consider them as separate parties. Obviously, this provided a unique opportunity to these small parties to present their programme and beliefs to the public at large, often not really being aware of its existence, let alone of its party programme (especially Vivant was unknown). In Belgian media coverage, these smaller parties are often marginalized and they only get a small share of the media attention cake. DVT gave them the chance to be taken seriously and to be treated just like the big parties. Moreover, as DVT only dealt with the content of parties’ programmes and not with the image of the party, its track record or its politicians, it reduced the small parties’ disadvantages considerably. Another potential advantage for the small parties was that they, unlike the big parties, often have an incomplete programme and no official stance regarding an issue. This gave them the opportunity to freely pick the most popular stance regarding many DVT statements since there were no official party stances to contradict their popular choices. In a nutshell, if there were any parties that may have got a boost from DVT, we expect it to be especially the small parties that were part of one of the three cartels with the traditional mainstream parties. Do we find such DVT effects in our panel?

Table 5 contains the evidence of a systematic comparison of users and non-users of DVT in terms of their vote intention change between wave 2 (before DVT) and wave 4 (after DVT). The figure +2.3 in the first column, for example, indicates that there were 2.3% more DVT users than non-DVT users switching towards CD&V–N-VA between waves 2 and 4. This suggests that getting a voting advice from DVT made people turn towards the CD&V–N-VA cartel. The negative figure −1.0 for Sp.a–Spirit in the first column indicates that there were 1% less people who shifted towards the leftist cartel among the DVT users than among the non-DVT users. The same logic applies to the fourth column but the signs have been reversed, with a negative sign indicating a bigger loss among DVT users and a positive sign a smaller loss among DVT users than among non-users. Significant differences have been printed in bold. The balance column combines both and assesses the net result of gain and loss due to DVT. As the N of gain and loss is not identical this column must be interpreted with caution.

Table 5 indicates that DVT users and non-users display a different electoral behaviour and that the electorates differ with respect to the effect of DVT on their vote. DVT did not cause major mass migrations but it appears as if small groups of voters may have been affected by DVT participation. On the significantly winning side we find Groen!, the green party and the liberal VLD–Vivant cartel. They won more voters among DVT users than they lost votes among DVT users. Losers were the extreme-right Vlaams Belang and the very small parties (‘other parties’) that were not represented in DVT. We do not know whether the progress of the liberal cartel is due to a better score of big partner VLD or small partner Vivant but we suspect the latter is true. Table 5 suggests, indeed, that smaller parties, for example Groen!, have more to gain from VAAs like DVT. Yet, very small parties that are excluded from VAAs, however, become even more marginalized and irrelevant in the eyes of the voter.

The analyses presented in Table 5 are bivariate and thus incomplete. We need to run multivariate analyses to check whether loss and gain among DVT users can be really attributed to their DVT use or rather to some of their other characteristics like age or education. In other words, what is the net effect of DVT use? We performed a number of logistic regression analyses comparing new and disloyal voters on the one hand with loyal voters (W2 to W4) of all parties on the other (Table 6). Apart from DVT use, we controlled for age, sex, education, interest in politics, left–right placement and the extent to which the campaign had been followed via the media (because a DVT effect could have been a sort of general media effect). All tendencies found in Table 5 remained significant in the multivariate analyses. DVT use has by far the strongest effect on switching to VLD–Vivant. Both CD&V–N-VA and Groen! significantly won votes among DVT users too. On the side of the significant losers we find, again, the CD&V–N-VA cartel, narrowly significant also the VLD–Vivant cartel and also the Vlaams Belang. The positive and negative effects compensate each other for CD&V–N-VA. Thus, finally, only VLD–Vivant and Groen! won votes because of DVT use while the Vlaams Belang lost votes. Note that the strength of the DVT effects in most of our multivariate models is rather small and, in spite of the large Ns, only passes the significance threshold narrowly. The explained variance of the models is also limited.

The subjective and objective impact of DVT combined

So far, we have presented subjective and objective evidence regarding the impact of DVT on the (intentional) votes of our panellists in 2004. Both measures are not always corresponding. For VLD–Vivant, the picture is clear: objectively (see Tables 5 and 6) as well as subjectively (see Table 3), the liberal cartel seems to have won votes due to DVT. For the CD&V–N-VA cartel, DVT seems to have made no difference, both subjectively and objectively. The leftist cartel Sp.a–Spirit seemed to have won subjectively, according to its voters, more than the greens of Groen! but the objective behavioural evidence points in the opposite direction. Also for the Vlaams Belang the results seem to be contradictory: subjectively, Vlaams Belang voters have hardly been affected by DVT, while the behavioural measures clearly showed that the Vlaams Belang lost votes due to DVT.

In this final empirical section, we compare both measures, attempting to shed more light on these contradictions. We want to check whether people who said DVT had raised doubts really changed party preferences. Therefore, in Table 7, we cross-tab vote (intention) behaviour change (W2 to W4) with the respondents’ subjective estimation of DVT's effect on their party preference. The table documents that, on average, only half of the people who said DVT made them doubt about their vote (8%) actually changed preferences. For the other half, DVT-inspired doubt did not have electoral consequences. Even among the small group of people saying that DVT really made them change their mind (1%), one third did not change their mind at all and remained loyal to the party, already getting their vote in wave 2. Overall, this tells us that the subjective impact of DVT is a rather unreliable measure of real electoral impact. Combining both figures, only 5% of our panellists say that their electoral preferences had somehow been affected by DVT and really changed their party preference. Which parties were the winners and losers?

We must be careful in interpreting the table as the basis (N) is often rather small, especially with regard to incoming and disloyal voters, but the differences between parties are substantial. Does the table confirm the findings presented above that the Vlaams Belang lost votes due to DVT while Groen! and especially the VLD–Vivant cartel won some votes? In terms of the Vlaams Belang, the contradiction between the subjective and objective impact measures above is maintained. Loyal (52%), incoming (59%) and disloyal (44%) Vlaams Belang voters all asserted more than average that DVT had had no effect at all on their vote. Of the voters leaving the Vlaams Belang between W2 and W4, only a very small group, smaller than average, pointed to DVT (3%). The opposite applies to the voters of Groen!. All types of (former) Groen!-voters least said that DVT had had no effect at all. DVT seemed to have confirmed the voting intention of many Groen!-voters (62%). These voters sought and found confirmation in DVT. At the incoming side, relatively much new Groen!-voters (4%) referred to DVT to explain their switch towards the greens. The liberal VLD–Vivant cartel is yet another story. Many loyal voters got a confirmation of their vote through DVT (57%). A relatively large group of new VLD–Vivant (7%) voters state that DVT made them change their mind. But also quite a few voters who turned their back on the liberal cartel, however, point to DVT as the culprit (8%). For CD&V–N-VA and Sp.a–Spirit, the results seem to go in the expected direction, indicating a clear impact of DVT neither on the winning nor on the losing side.

Wrapping up, combining both the subjective and the objective measures more or less confirms the outcomes of the vote intention change indicators for Groen! and VLD–Vivant. These parties seem to have won votes because of DVT. For the Vlaams Belang the picture is less clear: its (ex) voters claimed that DVT made no difference while the evidence about their changing vote intentions points in the opposite direction. Concerning CD&V–N-VA and Sp.a–Spirit, we can maintain that DVT was not an important source of inflow or outflow of voters.

Conclusion and Discussion

We stated earlier that VAAs are important because they may affect citizens’ electoral preference. A further spread of VAAs may, in particular, spur issue voting as voters may be relieved of a part of the information burden. In this study, we tested whether VAA use indeed affects the vote. We did not directly test whether VAA use changes the motivation for people's vote and thus increases issue voting — we leave that task for another time. Yet, if VAA use affects electoral preference, people who use a VAA vote for another party than people who do not use a VAA, we may safely conclude that probably the underlying motivation has also changed and that the vote has been more affected by issue positions of the parties than before. We found that party preference was only affected to a small extent by the ‘Do the Vote Test’ in Belgium in 2004 and, thus, that the ‘Do the Vote Test’ most likely did not cause a major shift among its users to issue voting. However, we did find some limited effects of VAA use on the vote. This suggests that the ‘Do the Vote Test’ effectively sparked a modest amount of issue voting.

Our analyses show in particular that the electoral effects of VAAs like DVT cannot be taken for granted. Based on a non-representative Internet panel, we scrutinized the electoral effects of DVT and found that effects were present, but modest and diverse. Not as much watching the TV show but rather using the online VAA to get a personalized voting advice seems to have affected a fraction of the Belgian electorate's preferences. In total, in our panel, only a few percent of the voters have been affected by DVT. As our panel is skewed and contains disproportionally many DVT users, we believe the effect of DVT in the Belgian population at large to be even smaller. Many people sought, foremost, confirmation of their existing preference through DVT, they were not seeking to be challenged. They tested the VAA system, not their own opinions nor the parties’ manifestoes. All Belgian parties won and lost due to DVT. Having said that, we showed that DVT gave some parties slight backing while other parties lost some support due to DVT.

These ‘limited effect’ results are somewhat in contrast with the research of Kleinnijenhuis et al. (2007) showing that VAAs played an important role in the recent Dutch election campaign. We see mainly three reasons for the modest effect DVT had on the Flemish electorate. First of all, the fact that there was not one, but three different versions of DVT, downplayed its influence. DVT users could get the advice to vote for the liberal party on issues regarding ‘norms and values’, but to vote for the socialist party on ‘economic’ issues. The often contradictory outcomes of the three shows made the DVT advice weaker. Secondly, the winners and losers of DVT, according to this research, are not the same as the winners and losers of the actual election outcome. The liberal cartel (VLD–Vivant) has probably benefited from DVT in 2004 but it lost a significant part of its electorate during the 2004 elections. On the other hand, the extreme right Vlaams Belang, which did not profit from DVT, took (another) a big step forward, becoming one of the largest Flemish parties. During the 2006 Dutch elections, the parties that did well in the VAAs (SP, PVV) were also the winners of the elections and the parties that got less VAA advices (PvdA, VVD) also suffered severe losses on election day. Probably the effect of a VAA is stronger when it confirms general trends — it reinforces the winner and causes a kind of bandwagon effect — and smaller as it goes against it. Thirdly, we focused on the direct effect of DVT on the voting behaviour of our panellist. These direct ‘strong’ effects on voting, we found, were limited but almost certainly more subtle, indirect effects are playing a role. A VAA perhaps cannot change a party preference but improve the identification with another party and make a future party change more likely. It may also draw attention to parties that remained beyond the scope of the voter's perception. In our current research, focussing on the 2007 elections, we try to tap these more fine-graded and indirect effects of VAAs.Footnote 11

The fact that DVT seems not to have changed many peoples’ opinion during the 2004 electoral campaign in Belgium does not exclude that VAAs like DVT might have other important consequences that are not immediately linked to the actual vote choice. We did not focus on these other, non-electoral DVT effects in this paper, but they are worth mentioning and contemplating. On the one hand, a possible consequence of rising participation in VAAs may be that VAAs boost the debate about issues and content, pulling away attention from secondary aspects of the campaign. VAAs are all about programmes, stances and issues, and this can be considered as a healthy thing for democracy. There are some indications in our panel data that this is actually the case. Voters who watched the ‘Do the Vote Test’ agreed more with the statement that they ‘learned something about the issue positions of different parties during the campaign’ than voters who watched none of the three TV shows. Almost 42% of our panellists who watched all three shows agree with this statement; among those who never watched the programme this was only 28%.Footnote 12 Furthermore, issue voting remained more important among participants of DVT than among our panellists who never used DVT. Panellists who used DVT assigned more importance to issue voting than those who did not participate already before the start of the programme (W1), but this difference has grown slightly after the programme (W5). Further research is needed to confirm these positive indications, especially to establish the link between issue voting and VAA use.

On the other hand, VAAs may affect how parties campaign. They may make parties follow the public instead of trying to convince the public to follow them. In other words, VAAs might stir populism. The fact that especially politicians believe that DVT had a strong effect on the public might influence their (campaign) behaviour, and become a self-fulfilling prophecy. VAAs may push them to develop more populist strategies to please the public.

Notes

This article is a thoroughly revised version of a paper that has been published before in Dutch (Walgrave and Van Aelst, 2005). An earlier version of this article was also presented at the ECPR joint workshop sessions April 2006 in Nicosia (Cyprus). We would like to thank all the participants of the workshop for their useful comments.

When we talk about ‘Belgium’ in this study, we actually mean Flanders, in the north of Belgium, where Dutch is spoken and containing about 60% of the Belgian population.

The authors of this paper have all been involved in elaborating and devising the ‘Do the Vote Test’-application in 2003 and 2004, organized by the national public broadcaster VRT. This involvement, we believe, does not affect our scientific judgement in this paper.

The semi-scientific journal Samenleving & Politiek has devoted a complete issue to the controversy about voting advice applications.

We contacted a sample of political scientists from all European countries and asked them to fill in a web survey about the existence and modalities of Voting Advice Applications in their country. Thirty-eight academics responded, giving us an initial idea of the situation in 22 countries: in 15 countries there has been a VAA, and in seven there has not (yet) been one. In 18 European countries, we were not able to find experts on this matter. Most are East-European countries, of which we are rather sure that there are no VAAs (e.g. Kazakhstan, Georgia). For more information on this expert survey, see Walgrave et al. (2008).

In the French-speaking part of Flanders, the commercial channel RTL hosted a smaller, less popular version of ‘Do the Vote Test’.

It concerns a web survey conducted in March 2006 among MPs and journalists in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. The response rate for politicians was 77% (N=202); for journalists, it was 66% (N=304). These data are part of a larger (ongoing) comparative survey in several European Countries.

We did not ask our respondents what party DVT advised them to vote for. Many people in our panel participated in the three separate VAAs regarding the different issue domains. This means they received sometimes three different advices. Consequently, it was very difficult to univocally measure the influence of a certain advice, as some people got three advices.

Some people stated that they did not watch DVT nor did they get a DVT voting advice and they still maintain that their voting behaviour had been affected by DVT. We think this is rather unlikely and, therefore, chose to exclude these people from the table.

A few months after the 2004 elections the extreme-right ‘Vlaams Blok’ changed its name into ‘Vlaams Belang’. For reasons of clarity we prefer to use this new name throughout the text.

In our 2007 Internet panel, we included more subtle questions like the likelihood of voting for different parties and detailed scores on the issue stances of parties. While the public broadcast opted for a single VAA (instead of three), we also asked for the actual vote advice people received. This should enable to search for smaller, indirect effects of DVT on voters.

This difference remained significant in a multivariate analysis controlling for age, gender, education, party preference and media use during the campaign.

References

Aardal, B. and van Wijnen, P. (2005) ‘Issue Voting’, in J. Thomassen (ed.) The European Voter, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 192–213.

Bartels, L.M. (1986) ‘Issue voting under uncertainty: an empirical test’, American Journal of Political Science 30 (4): 709–728.

Best, S.J. and Krueger, B.S. (2004) Internet Data Collection, Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dalton, J.R. and Wattenberg, M. (2000) Parties Without Partisans. Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dillman, D.A. (2000) Mail and Internet Surveys. The Tailored Design Method, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Downs, A. (1957) An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York: Harper and Row.

Goeminne, B. and Swyngedouw, M. (2007) ‘De verschuivingen in het stemgedrag’, in M. Swyngedouw, J. Billiet and B. Goeminne (eds.) De kiezer onderzocht. De verkiezingen van 2003 en 2004 in Vlaanderen, Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven, pp. 45–68.

Goren, P. (1997) ‘Political expertise and issue voting in presidential elections’, Political Research Quarterly 50 (2): 387–412.

Hooghe, M. and Teepe, W. (2007) ‘Party profiles on the web. An analysis of the log files of nonpartisan interactive political internet sites in the 2003 and 2004 election campaigns in Belgium’, New Media and Society 9 (6): 965–985.

Kleijnnijenhuis, J. and Krouwel, A. (2007) ‘The nature and influence of party profiling websites’, Paper presented at Politicologenetmaal, 31 May–1 June 2007, Antwerp, Belgium.

Kleinnijenhuis, J., Scholten, O., van Atteveldt, W., van Hoof, A., Krouwel, A., Oegema, D., de Ridder, J.A., Ruigrok, N. and Takens, J. (2007) Nederland Vijfstromenland: de rol van de media en stemwijzers bij de verkiezingen van 2006, Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Bert Bakker.

MacDonald, S.E., Listhaug, O. and Rabinowitz, G. (1991) ‘Issues and party support in multiparty systems’, The American Political Science Review 85 (4): 1107–1131.

Maddens, B. (1994) Kiesgedrag en partijstrategie. De samenhang tussen de beleidsmatige profilering van de partijen en het kiesgedrag van de Vlamingen op 24 november 1991. Leuven, Afdeling Politologie K.U.Leuven.

Schoen, H. (2000) ‘Gründe für Wechelndes Wahverhalten. Helfen neue Instrumente Licht in das Dunkel zu bringen?’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift 41 (4): 677–706.

Schuman, H. and Presser, S. (1981) Questions and Answers in Attitude Surveys. Experiments on Question Form, Wording, and Context, New York: Academic Press.

Swyngedouw, M., Billiet, J. and Carton, A. (1992) ‘Van waar komen ze? Wie zijn ze? Stemgedrag en verschuivingen op 24 november 1991’, ISPO-Bulletin, nr.3. Leuven.

Teepe, W. (2005) ‘Persoonlijke partijprofielen: een analyse vanuit de kennistechnologie’, Samenleving en politiek 12 (3): 2–12.

Van Praag, P. (2007) ‘De Stemwijzer: hulpmiddel voor de kiezers of instrument van manipulatie?’, Paper presented at Politicologenetmaal, 31 May–1 June 2007, Antwerp, Belgium.

Walgrave, S. and Van Aelst, P. (2005) ‘Much ado about almost nothing. Over de electorale effecten van Doe de Stemtest 2004’, Samenleving en Politiek 12 (3): 61–72.

Walgrave, S., Van Aelst, P. and Nuytemans, M. (2008) ‘Vote Advice Applications as new campaign players? Electoral effects of Do the vote test at the 2004 regional elections in Belgium’, in D. Farrell and R. Schmitt-Beck (eds.) The Role of Non-Party Actors in Elections (pp. 237–258), Baden-Baden: Nomos-Verlag Publishing House (pp. 237–258).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walgrave, S., van Aelst, P. & Nuytemans, M. ‘Do the Vote Test’: The Electoral Effects of a Popular Vote Advice Application at the 2004 Belgian Elections. Acta Polit 43, 50–70 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500209

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500209