Abstract

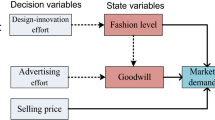

Design innovation is the engine of fashion. Many fashion firms outsource design innovation to their suppliers. Design outsourcing is on the rise in the fashion supply chain, but research in this area lags behind industry practice. In this paper, we examine how design outsourcing affects the supply chain, and we compare supply chain performance under an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) strategy versus an Original Design Manufacturer (ODM) strategy. We evaluate a market size outsourcing model where design enhancement influences market size, and a success probability outsourcing model where design enhancement influences the success probability of innovation. We find that when the supplier trades with the retailer via a wholesale price contract under the ODM strategy, the supplier has no incentive to invest in innovation. In the market size outsourcing model, the design innovation in the centralized supply chain is higher than that under the OEM strategy. However, in the success probability outsourcing model, the success probability of innovation under the OEM strategy is higher than that in the centralized supply chain. Furthermore, we find that a profit sharing contract can achieve supply chain coordination under both OEM and ODM strategies; whereas, revenue sharing and buyback contracts cannot.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We observe that the above discussed supply chain contracts have been adopted under the OEM and ODM strategies. However, for confidentiality issue, we do not disclose the company’s name.

References

Appelbaum RP (2011). Transnational contractors in East Asia. In: Hamilton G., Senauer B. and Petrovic B (eds). The Market Makers: How Retailers Are Reshaping the Global Economy. Oxford University Press: New York.

Baiman S, Fischer PE and Rajan MV (2001). Performance measurement and design in supply chains. Management Science 47 (1): 173–188.

Brun A and Castelli C (2008). Supply chain strategy in the fashion industry: Developing a portfolio model depending on product, retail channel and brand. International Journal of Production Economics 116 (2): 169–181.

Brun A et al (2008). Logistics and supply chain management in luxury fashion retail: Empirical investigation of Italian firms. International Journal of Production Economics 114 (2): 554–570.

Cachon GP (2003). Supply chain coordination with contracts. In: de Kok AG and Graves SC (eds). Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science: Supply Chain Management: Design, Coordination and Operation. North-Holland: Amsterdam, pp 229–340.

Cachon G and Lariviere M (2005). Supply chain coordination with revenue sharing contracts: Strengths and limitations. Management Science 51 (1): 30–44.

Cachon G and Swinney R (2009). Purchasing, pricing, and quick response in the presence of strategic customers. Management Science 55 (3): 497–511.

Çakanyıldırım M, Gan X and Sethi SP (2012). Contracting and coordination under asymmetric production cost information. Production and Operations Management 21 (2): 345–360.

Crystal Group (2014). Crystal Group website, http://www.crystalgroup.com/, accessed 15 July 2014.

Druehl C and Raz G (2014). The 3Cs of outsourcing innovation: control, capability, and cost. Working Paper. University of Virginia.

Feng Q and Lu LX (2011). Outsourcing design to Asia: ODM practices. In: Haksoz C, Seshadri S and Iyer AV (eds). Managing Supply Chains on the Silk Road: Strategy, Performance and Risk. CRC Press: New York.

Feng Q and Lu LX (2014). Design outsourcing in a differentiated product market: the role of bargaining and scope economies. Working Paper. Purdue University.

Hung H (2009). China and the Transformation of Global Capitalism. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kahn G (2003). Made to measure: Invisible supplier has Penney’s shirts all buttoned up. Wall Street Journal, 11 September.

Kaya O (2011). Outsourcing vs. in-house production: A comparison of supply chain contracts with effort dependent demand. Omega-International Journal of Management Science 39 (2): 168–178.

Lai ELC, Riezman R and Wang P (2009). Outsourcing of innovation. Economic Theory 38 (3): 485–515.

Lin C, Kuei CH and Chai KW (2013). Identifying critical enablers and pathways to high performance supply chain quality management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 33 (3): 347–370.

Plambeck EL and Taylor TA (2005). Sell the plant? The impact of contract manufacturing on innovation, capacity, and profitability. Management Science 51 (1): 133–150.

Shen B, Choi TM, Wang Y and Lo CKY (2013). The coordination of fashion supply chains with a risk-averse supplier under the markdown money policy. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 43 (2): 266–276.

Stanko MA and Calantone RJ (2011). Controversy in innovation outsourcing research: Review, synthesis and future directions. R&D Management 41 (1): 8–20.

Stanko MA and Olleros X (2013). Industry growth and the knowledge spillover regime: Does outsourcing harm innovativeness but help profit? Journal of Business Research 66 (10): 2007–2016.

Tsay AA (2001). Managing retail channel overstock: Markdown money and return policies. Journal of Retailing 77 (4): 457–492.

Wang Y, Niu B and Guo P (2013). On the advantage of quantity leadership when outsourcing production to a competitive contract manufacturer. Production and Operations Management 22 (1): 104–119.

Wang J and Shin H (2015). The impact of contracts and competition on unpstream innovation in a supply chain. Production and Operations Management 24 (1): 134–146.

Wei Y and Choi TM (2010). Mean-variance analysis of supply chains under wholesale pricing and profit sharing scheme. European Journal of Operational Research 204 (2): 255–262.

Wenting R (2008). Spinoff dynamics and the spatial formation of the fashion design industry, 1858–2005. Journal of Economic Geography 8 (5): 593–614.

Wu D (2014). Service quality, outsourcing and upward channel decentralization. Journal of the Operational Research Society 66 (4), xxxx.

Wu X and Zhang F (2014). Home or overseas? An analysis of sourcing strategies under competition. Management Science 60 (5): 1223–1240.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported in part by: (i) the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71401029), (71202066), (71172174); (ii) the Shanghai Pujiang Program (14PJ1400200); and (iii) the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

All proofs

Proof of Proposition 1

-

For (i), differentiating the profit function of retailer with respect to H and p, we find if 2β>e 2, π R (H, p) is jointly concave in both H and p. When ∂π R (p, H)/∂p=0 and ∂π R (p, H)/∂H=0, we yield p * OE (w)=[(1−e)βL−w(e−β)]/(2β−e 2) and H * OE (w)=[(1−e)eL−w(2−e)]/(2β−e 2). Substituting H * OE (w) and p * OE (w) into the profit function of supplier and differentiating it with respect to w, we assume H−p>0, thus when (1−e)(e−β)L>(β+2(1−e))k, w * OE is obtained. For (ii), differentiating the profit function of retailer with respect to p, we can show that π R (p) is concave in p and p * OD (H, w)=[eH+(1−e)L+w]/2. Substituting p * OD (H, w) into π S (H, w) and differentiating it with respect to w, we can obtain the unique optimal solution of the wholesale price, that is,

Substituting

Substituting  into π

S

(H, w) and differentiating it with respect to H, we can obtain that

into π

S

(H, w) and differentiating it with respect to H, we can obtain that  which is negative when β>(2−e)2/4. It implies that the lower bound of H is optimal, ie, H

*

OD

=L. Consequently, w

*

OD

=(L+k)/2 and p

*

OD

=(3L+k)/4 when L>k. Here, the condition L>k guarantees H−p>0.(Q.E.D.) □

which is negative when β>(2−e)2/4. It implies that the lower bound of H is optimal, ie, H

*

OD

=L. Consequently, w

*

OD

=(L+k)/2 and p

*

OD

=(3L+k)/4 when L>k. Here, the condition L>k guarantees H−p>0.(Q.E.D.) □

Proof of Proposition 2

-

For (i), differentiating the profit function of retailer with respect to e and p, we can find that if 2α>(H−L)2are met, π R (e, p) is jointly concave in both e and p. When ∂π R (p, e)/∂p=0 and ∂π R (p, e)/∂e=0, we yield e * OE (w)=(H−L)(L+w)/[2α−(H−L)2] and p * OE (w)=a(L+w)/[2α−(H−L)2]. Substituting e * OE (w) and p * OE (w) into the profit function of supplier and then differentiating it with respect to w, since H−p>0, namely when (2H−L−k)α>(H−L)2 H, w * OE is obtained. For (ii), differentiating the profit function of retailer with respect to p, we can show that π R (p) is concave in p and p * OD (e, w)=[eH+(1−e)L+w]/2. Substituting p * OD (e, w) into π S (e, w) and taking the first derivative with respect to e, we obtain that ∂π S (e, w)/∂e=−(w−k)(H−L)/2−∂e<0, implying that the lower bound of e is optimal, ie, e * OD =0. Substituting e * OD into π S (e, w) and taking the first and second derivatives with respect to w, we can obtain that π S (e * OD , w) is concave in w, and w*=(2H−L+k)/2. Consequently, we have p * OD =(2H+L+k)/4 when 2H>L+k. Here, the condition 2H>L+k guarantees H−p>0. Note that π R (p * OD )=(L−p)−w(H−p) when e * OD =0. Then in order to guarantee π R (p* OD )>0, we obtain that L 2+2Lk+12HL−12H 2−4Hk−k 2>0.(Q.E.D.) □

Proof of Proposition 3

-

For (i), differentiating the profit function of supply chain with respect to H and p, we find that if 2β>e 2, π SC (H, p) is jointly concave in H and p. We assume H−p>0, namely when (1−e)(e−β)L>(β+2(1−e))k, let ∂π SC (p, e)/∂p=0 and ∂π SC (p, e)/∂e=0, p * SC and H * SC are obtained. For (ii), similarly, differentiating the profit function of supply chain with respect to e and p, we find that if 2β>e 2, π SC (e, p) is jointly concave in e and p. Since H−p>0, we have when (1−e)(e−β)L>(β+2(1−e))k, e * SC and p* SC are obtained.(Q.E.D.) □

Proof of Proposition 4

-

(i), for H, since H * SC −H * OE =[(2−e)(w * OE −k)]/(2β−e 2)>0, we have H * SC >H * OE . Since H * OE is the optimal solution for

, we have H

*

OE

>L=H

*

OD

. Thus, H

*

SC

>H

*

OE

>H

*

OD

.

, we have H

*

OE

>L=H

*

OD

. Thus, H

*

SC

>H

*

OE

>H

*

OD

.For w, w * OE −w * OD =−[(1−e)L+(2−e)βL]/(2β+4(1−e))<0.

For p, p * SC −p * OE =[(e−β)(w * OE −k)]/(2β−e 2)>0=>p * SC >p * OE .

When A=((5e 2−4eβ−2β+2e−4)βL+2(3e+β)(e−β)(1−e)L)/((2−e)(β+2(1−e))e)⩾k, p * OE ⩾p * OD , otherwise, p * OE <p * OD . If B=(3Le 2−2(2e+1)βL)/((2e−2β+2e−e 2))⩾k, p * SC ⩾p * OD , otherwise, p * SC <p * OD .

Therefore, when A⩾k, p * SC >p * OE ⩾p * OD ; if B⩾k and A<k, p * SC ⩾p * OD >p * OE ; if A<k and B<k, p * OD >p * SC >p * OE

For (ii), w * OE −w * OD =−((H−L)2 H)/(2α)<0, so w * OE <w * OD .

For e, e * SC −e * OE =−(w * OE −k)(H−L)/[2α−(H−L)2]<0 and e * SC>e * OD =0, then e * OE >e * SC >e * OD .

For p, p * SC −p * OE =[H(H−L)2−(2H−L−k)α]/[2(2α−(H−L)2)]<0. The inequality holds by the condition (2H−L−k)α>(H−L)2 H in Propositions 2 and 3.

p * SC −p * OD =(−2(2H−L−k)α+(2H+L+k)(H−L)2)/(4[2α−(H−L)2]) , if (2H+L+k)(H−L)2>2(2H−L−k)α, p * SC ⩾p * OD , otherwise, p * SC <p * OD .

And p * OE −p * OD =((L+k)(H−L)2)/(4(2α−(H−L)2)>0, thus, if (2H+L+k)(H−L)2>2(2H−L−k)α, then p * OE >p * SC ⩾p * OD , otherwise, p * OE >p * OD >p * SC .(Q.E.D.) □

Proof of Proposition 5

-

For RS, we consider these four models one by one. For (i), first taking the first and second derivatives of π R (p, H) with respect to p and H, we can have when 2β>λe 2 (and this condition holds because of 2β>e 2), π R (p, H) is jointly concave in both p and H, then we can obtain p * OE (w)=(λβ(1−e)L+(β−λe)w)/λ(2β−λe 2) and H * OE (w)=(λe(1−e)L+(e−2)w)/(2β−λe 2).

If (H * SC , p * SC )=(H * OE , p * OE ) for some feasible solutions of λ and w, then we can say that the supply chain can achieve the coordination. By solving the equations (H * SC , p * SC )= (H * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that λ=1 and w=k, under which supplier obtains zero profit. Thus, revenue sharing contract cannot achieve the coordination for the OEM strategy with market size outsourcing model. For (ii), (iii) and (iv), similar approach is adopted.

For (ii), we have p * OD (w)=(2β(1−e)L+(w−k)(2−e)e)/(2(2β−(1−λ)e 2))+(w)/(2λ) and H * OD (w)=((1−λ)(1−e)eL+(w−k)(2−e))/(2β−(1−λ)e 2). By solving the equations (H * OD , p * OD )=(H * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that λ=w=0, under which retailer obtains zero profit. Thus, revenue sharing contract cannot achieve the coordination for the ODM strategy with market size outsourcing model.

For (iii), we have p * OE (w)=((λL+w)α)/(λ(2α−λ(H−L)2)) and e * OE (w)=(λL+w)(H−L)/(2α−λ(H−L)2). By solving the equations (e * SC , e * SC )=(e * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that λ=1 and w=k, under which supplier obtains zero profit. Thus, the revenue sharing contract cannot achieve the coordination for an OEM strategy with a success probability outsourcing model.

For (iv), we have p * OD (w)=((H−L)2(λk−w)+2α(λL+w))/(2λ(2α−(1−λ)(H−L)2) and e * OD (w)=((H−L)((1−λ)L+k+w)/(2α−(1−λ)(H−L)2). By solving the equations (e * SC , e * SC )=(e * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that λ=w=0, in which the retailer obtains zero profit.

Thus, the revenue sharing contract cannot achieve the coordination for an ODM strategy with a success probability outsourcing model. For BB, we also consider these four models one by one. For (i), first taking the first and second derivatives of π R (p, H) with respect to p and H, we can have when 2β>e 2, π R (p, H) is jointly concave in both p and H, then we can obtain H * OE (w)=((1−e)eL−(2−e)w+2(1−e)b)/(2β−λe 2) and p * OE (w)=((1−e)eb+β(1−e)L+(β−e)w)/(2β−e 2). If (H * SC , p * SC )=(H * OE , p * OE ) for some feasible solutions of b and w, then we can say that the supply chain can achieve the coordination. By solving the equations (H * SC , p * SC )=(H * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that b=0 and w=k, under which supplier obtains zero profit. Thus, buyback contract cannot achieve the coordination for the OEM strategy with market size outsourcing model. For (ii), (iii) and (iv), similar approach is adopted.

For (ii), we have H * OD (w)=(2(w−k)(2−e)−2(1−e)b)/(2β) and p * OD (w)=((w−k)(2−e)e−2(1−e)eb+2(1−e)βL+2βw)/(4β). By solving the equations (H * OD , p * OD )=(H * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that w * OD =k and b * OD =(βk(2−e)−(1−e)βeL)/((2β−e 2)(1−e))<0. Substituting w * OD and b * OD into supplier’s profit function, π S OD*=−β(H−L)((2β−e)L+k(2−e)/(2(2β−e 2))<0, supply chain fails to coordinate for the ODM strategy with market size outsourcing model.

For (iii), we have e * OE (w)=((L+w)(H−L)−2(H−L)b)/(2α−(H−L)2) and p * OE (w)=(α(L+w)−(H−L)2 b)/(2α−(H−L)2). By solving the equations (e * SC , e * SC )=(e * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that b=0 and w=k, under which supplier obtains zero profit. Thus, buyback contract cannot achieve the coordination for the OEM strategy with success probability outsourcing model.

For (iv), we have p * OD (w)=(2(H−L)2 b−(w−k)(H−L)2+2α(L+w))/(4α) and e * OD (w)=(2(H−L)b−(w−k)(H−L))/(2α). By solving the equations (e * SC , e * SC )=(e * OE , p * OE ), we obtain that w * OD =k and b * OD =(α(L+k))/(2α−(H−L)2).Substituting w * OD and b * OD into supplier’s profit function, π S OD*<0 Thus, buyback contract cannot achieve the coordination for the ODM strategy with success probability outsourcing model.

For PS, this is similar to Proposition 3, for (i) and (iii), first taking the first and second derivatives of retailer’s profit function, the results are same as Proposition 3; for (ii) and (iv), first taking the first taking the first and second derivatives of retailer’s profit function with respect to p and then taking the first and second derivatives of supplier’s profit function with respect to H or e, the results are same as Proposition 3. (H * OD , p * OD ) or (H * OE , p * OE ) are independent of φ. Thus supply chain can be coordinated.(Q.E.D.) □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, B., Li, Q., Dong, C. et al. Design outsourcing in the fashion supply chain: OEM versus ODM. J Oper Res Soc 67, 259–268 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2015.23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2015.23

Substituting

Substituting  into π

S

(H, w) and differentiating it with respect to H, we can obtain that

into π

S

(H, w) and differentiating it with respect to H, we can obtain that  which is negative when β>(2−e)2/4. It implies that the lower bound of H is optimal, ie, H

*

OD

=L. Consequently, w

*

OD

=(L+k)/2 and p

*

OD

=(3L+k)/4 when L>k. Here, the condition L>k guarantees H−p>0.(Q.E.D.) □

which is negative when β>(2−e)2/4. It implies that the lower bound of H is optimal, ie, H

*

OD

=L. Consequently, w

*

OD

=(L+k)/2 and p

*

OD

=(3L+k)/4 when L>k. Here, the condition L>k guarantees H−p>0.(Q.E.D.) □ , we have H

*

OE

>L=H

*

OD

. Thus, H

*

SC

>H

*

OE

>H

*

OD

.

, we have H

*

OE

>L=H

*

OD

. Thus, H

*

SC

>H

*

OE

>H

*

OD

.