Abstract

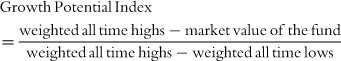

Several important breakthroughs within portfolio theory, capital asset pricing and return volatility have been made in the past few decades. Together with the liberalization of international capital asset trading, the global markets are set for an ever-improved efficiency and stability in the near future. Yet, from a small bank client's viewpoint, little has changed during almost five decades within the domain of financial investment support offered by the banks. With the focus of the contemporary research placed on advanced issues within portfolio theory, well-functioning financial markets and the growth impact of the banking sector, it seems as if the decision needs of the small bank client have been largely neglected. The risk measures currently used do not focus on the time of entry in a risky investment. Selecting a wrong entry point for fund investments can usually not be compensated by active governance within a reasonable investment period. In order to utilize the common practices in mutual fund investment services of the banks, a significant amount of knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of asset pricing and the fund dynamics is required from the investor. In the current note, we present a simple statistic, the Growth Potential Index (GPI), which captures the essential characteristics of relevance for determining the time of entry in a mutual fund investment. The mirror image of the GPI, the Decline Potential Index (DPI), is also presented. The DPI may provide valuable decision support information for specifying the time of exit from a long position in the fund. As GPI and DPI are simple to understand and calculate and contain valuable decision support information for a small client, their inclusion in the websites would seem to be a worthwhile effort for any esteemed financial institution offering stock governance services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The time of entry in a risky investment is of critical importance, yet the information support needs for small investors have currently not the attention they deserve.1, 2 Even though the theoretical literature on the linkage between long-run economic growth, well-functioning stock markets and fair investment opportunities is abundant, the actual empirical evidence on the connection is relatively scarce. The study by Levine and Zervos3 demonstrates a connection between stock market liquidity and banking development in relation to growth, capital accumulation and productivity improvement in the US market (cf. Khan4). On the other hand, the volatility of the stock market has been investigated in numerous empirical studies globally ever since the path-breaking models by Engle5 and Bollerslev.6 For example, the stock return volatility of the Scandinavian stock markets in relation to the banking sector and certain key events like the liberalization of the Finnish stock market was investigated by Hyytinen.7 He found a significant connection between volatility shifts and times of Finnish bank crisis.

Furthermore, abundant research on risky investments based on portfolio theory has emerged ever since the path-breaking mean-variance theory of efficient portfolios put forward by Markowitz.8 However, for the small investor operating in real-world conditions with economic friction, a mean variance equilibrium model gives insufficient decision support.9 The question of when to enter in a risky investment and how to optimally respond to changing market conditions by adjusting the portfolio composition under fixed and variable transactions costs remains unanswered in the Markowitz world (cf. Mandelbrot and Hudson10). According to the mutual fund separation theorem (cf. Sharpe,11 Lintner,12 Mossin13), more risk-averse investors should hold more of their assets in the riskless asset, whereas the composition of the risky asset should be identical for all investors. Canner et al14 observed that, contrary to the theorem, public advisors recommend more complicated strategies than implied by the theorem.15

Multi-period portfolio theory combined with rigorous statistical time-series algorithms and techniques anchored in artificial intelligence seem to comply with real-world conditions better than those strictly based on the mutual fund theorem (cf. Hoklie16). For example, the question of when to enter in a risky investment can be explicitly addressed.17 An additional advantage of multi-period formulations is that they are robust with respect to, for example, non-stationary returns or unknown return distributions.18 At the same time, artificial intelligence-based techniques can cope with non-stationarity, regime shifts and related difficulties encountered in financial time-series estimation.19, 20 Contrary to single-period equilibrium models, fixed/variable rebalancing costs are readily incorporated in multi-period models.21

Yet, from a small bank client's viewpoint, little has changed during the past five decades within the domain of financial investment support offered by the banks. With the focus of the contemporary research placed on issues such as portfolio theory, well-functioning financial markets and the growth impact of the banking sector, it seems as if the practical decision needs of the small bank client have been largely neglected.22 Selecting a wrong entry point for risky investments can usually not be compensated by active fund management within a reasonable investment period. In order to utilize the common practices in mutual fund investment services of the banks, a significant knowledge of the underlying mechanisms of asset pricing and the fund dynamics is currently required from the investor. Owing to the lack of information, a fairly safe entry time for fund investments is currently offered only in times of an exchange crash. Frequently used measures such as the Sharpe ratio, characterizing the return compensation of a risky investment,23, 24, 25 Roy's safety-first criterion or the Bias ratio26 do not consider the time of entry. With regard to the importance of well-functioning global financial markets, the current state does not seem to be satisfactory.27

With the focus of the current note laid on the small investor's viewpoint, we will subsequently consider the following question in more detail, assuming that a long position in a financial instrument is contemplated by the investor:

Is the current value of the most important (stock, bond, and so on) holdings in the instrument (for example, mutual fund, index bond, warrant, and so on) – covering at least 80 per cent of the value of its (stock, bond, and so on) portfolio – near the ‘all time high’ or ‘all time low’ price level over a past period of T years from the observation time point t backwards?

This simple question is not readily answered using the computer resources currently available, for example, to Finnish bank clients. Yet, the question is of fundamental importance for the decision making of small investors, most of which contemplate allocating their personal savings from wage earnings as meaningfully as possible. The problem formulation of this note is linked to managing the downside risk of financial portfolios28 and to contrarian investment strategies.29

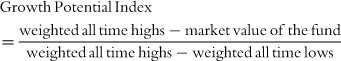

THE GROWTH POTENTIAL INDEX

Assume that the computer system of a bank did produce the following simple summary information for (say, 10) evaluation time points (days) in year 2009, for example:

-

1

Ω2009={19. 11, 20.11, 21.11, …, 28.11}.

-

2

P t =market value of the fund (portfolio) at the evaluation time t∈Ω2009.

-

3

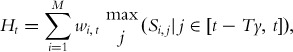

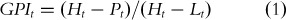

H t =weighted all time highs over the last T years for the M assets in the fund at the evaluation time point t:

where wi,t is the weight of asset i in the portfolio at time t, Si,t is the price of asset i at time t and y denotes the number of exchange days in a year.

-

4

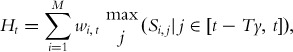

L t =weighted all time lows over the last T years,

-

5

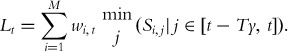

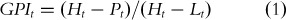

GPI t =growth potential of the portfolio at the evaluation time point t: if(H t >L t ,t∈Ω2009) {

or:

} else {GPI t =0}.

We would use the market value of each stock in the fund relative to its total value at the evaluation time points as the weights.

Remark

-

GPI t cannot be obtained directly from the historical profile of the aggregate instrument, unless the portfolio composition of the instrument is constant over time.

Proof: The all-time high of P t at time t is defined as

Assume that wi,j is constant over time, that is, wi,j=wi,t=w i , ∀j, t. Then we can rewrite (3) as

□

The proof holds analogously for the all-time lows L t and Pt,min, respectively.

GPI t and DPI t are mirror images in [0, 1], where the latter may be used as an indicator for selling a long position in the asset. In the subsequent analysis, we focus on GPI t only. We note that GPI t is a stochastic variable whose distributional characteristics are intimately connected to those of the underlying instrument.

Refinements of GPI t in order to recognize, for example, the volatility of the instrument or the time interval between the highs and lows of individual stocks – a kind of discounted GPI t – are conceivable but will not be dealt with here: for example, if H t has occurred recently for a given stock i, then it is not too likely that its price will increase rapidly even though its stock level GPIi,t could be high. Hence, two different financial instruments with the same GPI t may (and probably will) perform differently over time.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ASSET MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE POLICIES

Now, given the simple facts (1)–(4), we could indicate the growth potential of the fund by a practical number between [0, 1] using formula (5) – up to the extent of the validity of the historic volatility for modeling expected returns. The closer this index is to one, the more growth potential we have in the portfolio and the more we should consider actually investing in the instrument – after analyzing the components of the fund more closely and perhaps discussing with different experts. The subset of funds with a low GPI t at the time of possible investment is less attractive than the subset with a high GPI t .

Two stocks with different GPIi,t profiles are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Assume that the investor is offered two alternative funds (f1, f2) with roughly the same reputation and financial profile (return history, volatility, type of stocks in the fund, intelligence resources behind the fund investment activities and so on) by his/her personal bank advisors in two competing financial institutions, say, Bank 1 and Bank 2. Assume that one share of each fund has the same acquisition cost and that the growth potential index GPI is ⩽0.1 for the first and ⩾0.9 for the second at the observation time point or a relevant set of evaluation time points. Which one of them should be considered? Irrespectively of the argumentation of the competing bank, the fund f2 would be the natural choice for deeper investigation.

In the current state of affairs with low interest rates and low stock prices, people are recommended – many by their personal bank advisors – to invest in stocks, funds and other financial instruments like warrants and derivatives in general. But if the instrument consists predominantly of components with a return profile analogous to the one in Figure 1, we usually cannot expect significant price increases of the fund in the near future – not even over longer time periods like 7–9 years. The fund is low GPI. In that case, people tend to be wrongly advised to invest in funds that actually do not have the potential to yield the implied return between the investment time point and a reasonable future time point. The fund has a high probability of negative returns during the next 7–9 years. If the investor has a long position in a low GPI fund, he probably should follow the recommendation by Alexander30: ‘It almost always pays to bite the bullet to get out of an underperforming … fund and start over again. The longer you keep a poor … fund, the longer compound interest is working against you as compared with alternative investments carrying less dead weight’. GPI summarizes facts that anybody can understand: the more you pay for a product at time t, the less probably you will earn a (high) profit within a reasonable time span. The relevance of GPI of course is dependent on the risk attitude and time horizon of the investor: the planning horizon and mistake potential of an investor in his/her early twenties may differ from that of an investor in his nineties. But all investors prefer high GPI funds over low GPI funds at the time of investment irrespective of their risk attitude or planning horizon. We can never change that. Neither can we change the fact that the more high GPI fund investors a bank has, the greater will be the trust in the bank and its fund management. The lower the number of high GPI customers, the lower will be the trust in the bank and the higher the incentive to reallocate the savings to competing financial institutions.

GPI says nothing about the predictability of stock returns or about the validity of the return history in decision making.31 Yet, the efforts of the fund manager will become misjudged and cannot receive the appreciation they deserve by people who never obtain a reasonable return simply because the investment time point was specified without using the appropriate intelligence in the first place. In large banks, the fund management and adviser services are usually decentralized to different experts. The fund manager is not responsible for the investment advice provided by personal bank advisors.32 Neither can the personal advisors provide the GPI-information needed because of the lack of computer systems. This is a significant policy issue for any modern bank organization operating with outdated information systems and insufficient decision support principles for small investors. The Finnish banks in general have the intelligence and information required for adequate decision support, but they do not use them appropriately: surely, one cannot expect a small investor in, for example, a stock or an interest fund to somehow dig out the answers to simple questions concerning the history of the fund, because the million euro computer systems of the bank do not provide the simple calculations involved. The GPI profiles of mis-investments in funds at the wrong time point should be appropriately calculated and discussed in the organizations to ensure an improved use of people's earned money, trusted in the hands of the bank's representatives. When the trust is lost, it is not easily earned back.

A sound policy might be not to trust financial assets in the governance services of a bank that cannot generate the relevant GPI-information, unless the history of the fund itself indicates a bear market without a reasonable doubt, for example due to an exchange crash.

On the other hand, if the fund consists predominantly of firms with a return profile resembling the one in Figure 2 at the time of investment, significant price increases and a corresponding return on the risky fund investment may be expected within a reasonable time span, as we are dealing with a high GPI fund. By choosing a high GPI investment time point, the work of the fund manager and the personal bank advisor is more likely to be appreciated as it should.

GPI and the return history of the fund jointly reflect the efficiency of fund management: the higher the return of the fund – relative to competing instruments or a comparison index – and the higher the GPI t time series, the more frequently the instrument will provide profitable investment opportunities over time. Hence, the lower will be the overall risk of mis-investment in the instruments of the bank.

The investment support system of a bank in the modern information society should incorporate suitable alarm triggers and the possibility to extract critical summary statistics such as GPI in combination with the traditional measures. For example, assume that the investor is allowed to enter the following condition in the information system of the bank:

If the five-year GPI t 5 of any instrument (mutual stock/interest/hedge/combined fund, index bond or another) of BANK Q exceeds 0.75, send an alarm.

Now, if this condition is activated at any time, the alarm is triggered in the form requested by the (potential) investor, that is, as a normal email or through a phone call by the personal bank advisor.

The email would state: ‘important message received from the Bank Q, please log into your bank and check your message’.

When the investor logs into the system, he can read the following message:

Your condition GPI t 5⩾0.75 was met by [the mutual stock fund BANK Q HEDGE ABC] on [dd.mm.yyyy at hh.mm.ss]. Please contact your personal bank advisor [first name] [last name], phone number [+ccc xxx xxx xxxx] for further discussions and consultation.

This simple construct would provide a meaningful basis for discussions directly to the point.

CONCLUSIONS

GPI like any other construct cannot guarantee successful financial investments. A low GPI fund may actually turn out be a good investment, at least in a fairy tale. For example, if the valuable stocks of the fund at time t can and will be realized in the near future and switched to low price stocks with a high return potential, then a fund investment may be justified at time t. However, if such a switch is probable, why not simply wait for it to occur and implement the investment when the fund turns high GPI? When contemplating potential fund investments, the small investor neither has the time nor the possibility – already because of confidentiality – to inquire about the possible future investment decisions of a fund manager. In a global exchange crash, the return history of the fund is a more reliable basis for decision making than at other times. However, personal bank advisors seldom if ever do contact their clients with fund investment proposals during a crash. This brings us to the following question:

Is it badwill for the bank to allow/urge its personal advisors to turn to their clients in an exchange crash with the following message: ‘our funds have fallen down heavily in the current global recession; they are now suitable investment objects’?

Note that the discussion on GPI should not be confused with dynamic portfolio (re)balancing and active portfolio management under transaction costs.33 The duty of a fund manager is to take care of portfolio management for their clients. But the clients need to know the proportion of cheap/expensive stocks and other possible components in the financial instrument at the time of investment. Therefore, the bank advisors should be provided with the capacity – usually backed up by a considerable staff of experts in financial asset pricing and fund management – to provide the above simple information to potential investors.

From the small investor's perspective, the need for simple decision support information especially for determining the time of entry in a financial instrument governed by the bank seems to be self-evident. An unfavorable time of entry can usually not be compensated by active fund management within a reasonable time span. Hence, there is a need for specifying the suitable decision support information for small investors contemplating, for example, fund investments through the banking sector.

In the current note, we present a simple statistic, the Growth Potential Index, which captures the essential characteristics of relevance for determining the time of entry in a mutual fund investment. The mirror image of GPI, the Decline Potential Index, is also presented. DPI may provide valuable decision support information for specifying the time of exit from a long position in the fund. As GPI and DPI are simple to understand and calculate and contain valuable decision support information for a small client, their inclusion – possibly in refined form – in the websites of the banks would seem to be a worthwhile effort.

References

Taleb, N., Goldstein, D. and Spitznagel, M. (2009) The six mistakes executives make in risk management. Harvard Business Review 87 (10): 78–81.

Tu, J. and Zhou, G. (2011) Markowitz meets Talmud: A combination of sophisticated and naïve diversification strategies. Journal of Financial Economics 99: 204–215.

Levine, R. and Zervos, S. (1998) Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. The American Economic Review 88 (3): 537–558.

Khan, A. (2000) The finance and growth nexus. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Business Review, January/February, pp. 1–14.

Engle, R. (1982) Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity with estimates of the variance of UK inflation. Econometrica 50 (4): 987–1008.

Bollerslev, T. (1986) Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics 31 (3): 307–327.

Hyytinen, A. (1999) Stock Return Volatility on Scandinavian Stock Markets and the Banking Industry Evidence from the Years of Financial Liberalization and Banking Crisis. Bank of Finland Discussion Papers 19.

Markowitz, H. (1952) Portfolio selection. Journal of Finance 7 (1): 77–91.

Kürschner, M. (2008) Limitations of the Capital Asset Pricing Model. München, Germany: Grin Verlag.

Mandelbrot, B. and Hudson, R.L. (2004) The (Mis)Behaviour of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin, and Reward. London: Profile Books.

Sharpe, W.F. (1964) Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. Journal of Finance 19 (3): 425–442.

Lintner, J. (1965) The valuation of risky assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. Review of Economics and Statistics 47 (1): 13–17.

Mossin, J. (1966) Equilibrium in a capital asset market. Econometrica 34 (4): 768–783.

Canner, N., Mankiw, G. and Weil, D. (1997) An asset allocation puzzle. American Economic Review 87 (1): 181–191.

Rakow, T. and Newell, B. (2010) Degrees of uncertainty: An overview and framework for future research on experience-based choice. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 23 (1): 1–14.

Hoklie, Z. (2010) Resolving multi objective stock portfolio optimization problem using genetic algorithm. The 2nd International Conference on Computer and Automation Engineering (ICCAE); ISBN 978-1-4244-5585-0. DOI 10.1109/ICCAE.2010.5451372, pp. 40–44.

Östermark, R. (1991) Vector forecasting and dynamic portfolio selection. Empirical efficiency of recursive multiperiod strategies. European Journal of Operational Research 55: 46–56.

Grauer, R. and Håkansson, N. (1986) A half century of returns on levered and unlevered portfolios of stocks, bonds and bills, with and without small stocks. Journal of Business 59 (2): 287–318.

Östermark, R. (2002) Automatic detection of parsimony in heteroskedastic time series processes. Empirical tests on global asset returns with parallel geno-mathematical programming. Soft Computing 6 (1): 45–63.

Östermark, R. (2010) Concurrent processing of heteroskedastic vector-valued mixture density models. Journal of Applied Statistics 37 (9–10): 1637.

Puelz, A. (2002) A stochastic convergence model for portfolio selection. Operations Research 50 (3): 462–476.

Eastaway, N.A., Booth, H., Eamer, K., Elliott, D. and Kennedy, S. (2009) Practical Share Valuation, 5th edn. Haywards Heath, UK: Tottel Publishing.

Sharpe, W.F. (1966) Mutual fund performance. Journal of Business 39 (S1): 119–138.

Sharpe, W.F. (1994) The Sharpe ratio. Journal of Portfolio Management 21 (1): 49–58.

Scholz, H. (2007) Refinements to the Sharpe ratio: Comparing alternatives for bear markets. Journal of Asset Management 7 (5): 347–357.

Weinstein, E. and Abdulali, A. (2002) Hedge fund transparency: Quantifying valuation bias for illiquid assets, www.risk.netRisk, risk management for investors; June, 25–28.

Hubbard, D.W. (2009) The Failure of Risk Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-38795-5.

Merriken, H. (1994) Analytical approaches to limit downside risk: Semi variance and the need for liquidity. The Journal of Investing 3 (3): 65–72.

Hagström, R.G., Miller, B.R. and Fisher, K. (2005) The Warren Buffett Way. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, ISBN 0-471-74367-4.

Alexander, C. (2006) Streetsmart Guide to Timing the Stock Market: When to Buy, Sell and Sell Short, 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-146105-1.

Östermark, R. (2005) Dynamic portfolio management under competing representations. Kybernetes: The International Journal of Systems and Cybernetics 34 (9/10): 1517–1550.

Swensen, D. (2000) Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment. New York, NY: The Free Press, May.

Östermark, R. (2011) Hedging with options and cardinality constraints in multi-period portfolio management systems. Kybernetes: The International Journal of Systems and Cybernetics 40 (5/6): 703–718.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Östermark, R. A short note on the Growth Potential of risky fund investments. J Deriv Hedge Funds 17, 281–290 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/jdhf.2011.22

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jdhf.2011.22