Abstract

This paper considers an alternative perspective to China’s exchange rate policy. It studies a semi-open economy where the private sector has no access to international capital markets but the central bank has full access. Moreover, it assumes limited financial development generating a large demand for saving instruments by the private sector. The paper analyzes the optimal exchange rate policy by modeling the central bank as a Ramsey planner. Its main result is that in a growth acceleration episode it is optimal to have an initial real depreciation of the currency combined with an accumulation of reserves, which is consistent with the Chinese experience. This depreciation is followed by an appreciation in the long run. The paper also shows that the optimal exchange rate path is close to the one that would result in an economy with full capital mobility and no central bank intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For some recent contributions on this debate, see Cheung, Chinn, and Fujii (2011), Frankel (2010), or Goldstein and Lardy (2008).

See Obstfeld and Rogoff (1996, ch. 4). For example, Obstfeld and Rogoff (2000, 2007) use this standard framework to analyze U.S. net saving and the dollar exchange rate.

This implies that a capital account liberalization would lead to a net private capital outflow. Several papers in the literature predict such an outcome for China using totally different perspectives. For example, see He and others (2012a).

This simple framework with credit constraints enables to capture two key features found in the recent literature on global imbalances: insufficient supply of domestic assets (see Caballero, Farhi, and Gourinchas, 2008) and precautionary saving (see Mendoza, Quadrini, and Ros-Rull, 2009).

Since 2000, the Chinese central bank has increased its liabilities with the domestic banking sector at about the same rate as international reserves. These liabilities mainly take the form of central bank bonds and commercial banks reserves.

In a recent paper, Jeanne (2012) considers a semi-open economy with traded and nontraded goods and shows how exogenous changes in international reserves alter intertemporal consumption choices, as well as the real exchange rate.

Farhi, Gopinath, and Itskhoki (2012) show that a simple combination of taxes can replicate nominal exchange rate policy, but they do not consider a Ramsey planner.

We focus on the years 2000 as China was not truly a market economy until the late 1990s. For instance, a significant share of producer and retail prices were not market-determined until the second half of the 1990s. The People’s Bank of China only became an autonomous central bank in the modern sense after a law was passed in March 1995. See OECD (2009) for details on the reform process.

We consider a real model and do not model inflation explicitly. Introducing a nominal sector with flexible prices would allow to distinguish between nominal and real exchange rate fluctuations, but would not change our main analysis. Notice, however, that the nominal trade-weighted RMB has moved closely to its real value since 2000.

For example, Bianchi (2011), Korinek (2011), Benigno and others (2013). Céspedes, Chang, and Velasco (2012) examine central bank intervention with such an externality in the context of capital inflows.

In general there can be differences between the relative price of traded and nontraded goods and the commonly measured real exchange rate. We will abstract from these differences. He and others (2012b) estimate that in the case of China the relative price of traded and nontraded goods shows a stronger appreciation in recent years than standard real exchange rates measures.

There are four basic differences with Woodford (1990):(i) consumers may be able to borrow; (ii) there is a Ramsey planner; (iii) there is no capital stock; (iv) there are traded and nontraded goods.

This simple structure can account for three major explanations for the Chinese propensity to save that are rooted in the lack of welfare state: income risk, the need for savings in the perspective of health-related expenditures, and retirement. Other factors can explain high saving in China (for example, see Yang, Zhang, and Zhou, 2011), such as education or the gender imbalance, but adding these factors would not change the main results of our analysis.

In the absence of uncertainty, the denomination of assets has no consequence on equilibrium allocations.

In reality, the lending between high and low endowment households goes through the banking sector, with bank deposits and bank loans. However, modeling financial intermediaries would not affect our analysis.

In practice, central banks usually transfer their profits to the government, which relaxes the government budget constraint. In Bacchetta, Benhima, and Kalantzis (2013), we explicitly introduce the government and distortionary taxes.

This is an important assumption since this prevents the central bank from borrowing from the rest of the world and distribute resources to the households in order to overcome the borrowing constraints. It is however realistic since most central banks distribute profits on an annual basis (this is similar to the assumption made in many models that firms distribute all their profits every period).

This equation follows from the Euler equation (5) and the budget constraints ((equations (2) and (3)).

For example, with log-utility and β=0.95, this condition holds as long as tradable consumption represents at least 2.5 percent of total consumption.

Given the household budget constraints and the market-clearing conditions, the current account identity is equivalent to the budget constraint of the central bank.

From Proposition 2, we already know that it is optimal to accumulate reserves in the steady state when φ=0.

This holds under the veil of ignorance, that is if the households did not know whether they would switch to a semi-open economy when they are borrowers or when they are savers. However, both borrowers and savers would agree to switch, as they respectively gain the equivalent of 7.5 percent and 7.3 percent of their consumption under the closed economy.

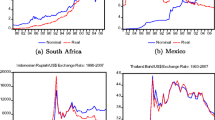

Authors’ calculation based on the World Development Indicators from the World Bank.

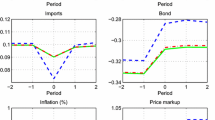

As apparent in the graph, the real exchange rate might exhibit some mild oscillations. This is due to heterogeneity: the motive for changing the real exchange rate can fluctuate over time as the agent with higher marginal utility switches from borrower to saver. This is the case in the simulation with a higher σ, where the real exchange rate initially depreciates before appreciating again. Initially, the planner accumulates reserves in order to maintain a high interest rate, which benefits the initial saver (this is captured by R1) at the expense of the initial borrower (this is captured by R2 and R3). Because σ is larger, this however depreciates the currency even more than in the baseline simulation, which hurts the initial borrower further by decreasing revenues and making the constraint more stringent (these effects are summarized by P1 and P2 respectively). The following appreciation compensates for that by stimulating the next period’s revenues of the initial borrower (P1′ term).

References

Aghion, Ph., Ph. Bacchetta, R. Rancière, and K. Rogoff, 2009, “Exchange Rate Volatility and Productivity Growth: The Role of Financial Development,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 56, No. 4, pp. 494–513.

Bacchetta, Ph., K. Benhima, and Y. Kalantzis, 2013, “Capital Controls with International Reserve Accumulation: Can this Be Optimal?,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 226–62.

Benigno, G. and and others 2013, “Financial Crises and Macro-Prudential Policies,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 89, No. 2, pp. 453–70.

Benigno, G. and L. Fornaro, 2012, “Reserve Accumulation, Growth and Financial Crisis,” mimeo.

Bianchi, J., 2011, “Overborrowing and Systemic Externalities in the Business Cycle,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 7, pp. 3400–426.

Caballero, R. J., E. Farhi, and P.-O. Gourinchas, 2008, “An Equilibrium Model of ‘Global Imbalances’ and Low Interest Rates,” American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 358–93.

Céspedes, L. F., R. Chang, and A. Velasco, 2012, “Financial Intermediation, Exchange Rates, and Unconventional Policy in an Open Economy,” NBER Working Paper No. 18431.

Cheung, Y. W., M. Chinn, and E. Fujii, 2011, “A Note on the Debate over Renminbi Undervaluation,” in China and Asia in the Global Economy, ed. by Y. W. Cheung and G. Ma (Singapore: World Scientific).

Farhi, E., G. Gopinath, and O. Itskhoki, 2012, “Fiscal Devaluations,” mimeo.

Frankel, J., 2010, “The Renminbi Since 2005,” in The US-Sino Currency Dispute: New Insights from Economics, Politics and Law, ed. by Simon Evenett (London: VoxEU), April, pp. 51–60.

Goldstein, M. and N. R. Lardy, 2008, Debating China’s Exchange Rate Policy (Washington, DC: The Peterson Institute for International Economics).

He, D., L. Cheung, W. Zhang, and T. Wu, 2012a, “How Would Capital Account Liberalization Affect China’s Capital Flows and the Renminbi Real Exchange Rates?” HKIMR Working Paper No. 09/2012.

He, D., W. Zhang, G. Han, and T. Wu, 2012b, “Productivity Growth of the Non-Tradable Sectors in China,” HKIMR Working Paper No. 08/2012.

Jeanne, O., 2012, “Capital Account Policies and the Real Exchange Rate,” NBER Working Paper No. 18404.

Korinek, A., 2011, “The New Economics of Prudential Capital Controls,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 523–61.

Korinek, A. and L. Servén, 2011, “Undervaluation through Foreign Reserve Accumulation: Static Losses, Dynamic Gains,” mimeo.

McKinnon, R., 2010, “Why China Shouldn’t Float,” The International Economy, Fall, pp. 34–37.

Mendoza, E. G., V. Quadrini, and J.-V. Ríos-Rull, 2009, “Financial Integration, Financial Development, and Global Imbalances,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 117, No. 3, pp. 371–416.

Obstfeld, M. and K. Rogoff, 1996, Foundations of International Macroeconomics (Cambridge: MIT Press).

Obstfeld, M. and K. Rogoff, 2000, “Perspectives on OECD Economic Integration: Implications for US Current-Account Adjustment,” in Global Economic Integration: Opportunities and Challenges, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Annual Monetary Policy Symposium.

Obstfeld, M. and K. Rogoff, 2007, “The Unsustainable U.S. Current Account Deficit Revisited,” in G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, ed. by R. H. Clarida (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

OECD. 2009, “China, Defining the Boundary between the Market and the State,” OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

Song, Z.M., K. Storesletten, and F. Zilibotti, 2011, “Growing like China,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 1, pp. 202–241.

Woodford, M., 1990, “Public Debt as Private Liquidity,” American Economic Review, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 382–88.

Yang, D. T., J. Zhang, and S. Zhou, 2011, “Why Are Saving Rates so High in China?” NBER Working Paper No. 16771.

Additional information

*Philippe Bacchetta is a Swiss Finance Institute Professor at the University of Lausanne (HEC) and a CEPR Research Fellow. Kenza Benhima is a Professor at the University of Lausanne (HEC) and a CEPR Research Affiliate. Yannick Kalantzis is a Senior Economist at the Banque de France. The authors would like to thank two referees, Menzie Chinn, Roberto Chang, Nicolas Coeurdacier, Giovanni Lombardo, Charles Engel, as well as participants at seminars at the City University of Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Università di Napoli Federico II, the London Conference on International Capital Flows and Spillovers, the Bank of Canada—ECB workshop on exchange rates, and the Summer Workshop in International Finance and Macro Finance, for useful comments. Bacchetta and Benhima gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Centre of Competence in Research “Financial Valuation and Risk Management” (NCCR FINRISK). Bacchetta also acknowledges support from the ERC Advanced Grant #269573, and the Hong Kong Institute of Monetary Research.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

Equations (5) and (6), taken in the steady state, imply that (βr)2(1+λ)=1. As λ≥0, it follows that βr≤1. Therefore, we look for an equilibrium interest rate r∈(0,r*].

Assume first that the borrowing constraint (equation (4)) is binding. Then, using the demand for bonds (equation (19)) and the fact that B t *=B t , the market-clearing condition for bonds (equation (11)), taken in the steady state, can be rewritten:

From the profit distribution (equation (14)), we have π=(r*−r)B*=(1/β−r)B*. Then, 1/r is the solution of a third-degree polynomial: P(1/r)=0, with

where Y/YT can be derived from Equation (18):

We have P(0)≥0 for B*≥0. In addition, P(β)=P(1/r*)<0 if and only if

This condition is equivalent to  when the left-hand side is strictly positive, which we have assumed. Finally, P(X)→+∞ when X→+∞ and P(X)→−∞ when X→−∞. It follows that P has three roots: one negative root, one root on (0, β), and one root on (β,+∞). Since the equilibrium interest rate has to be in (0,r*], we must have X≥β so that we can discard the first two roots. We conclude that there is a unique interest rate r∈(0,r*] that clears the market for bonds and that this interest rate is strictly lower than r*. Given r, it is straightforward to derive all the other variables in the steady state.

when the left-hand side is strictly positive, which we have assumed. Finally, P(X)→+∞ when X→+∞ and P(X)→−∞ when X→−∞. It follows that P has three roots: one negative root, one root on (0, β), and one root on (β,+∞). Since the equilibrium interest rate has to be in (0,r*], we must have X≥β so that we can discard the first two roots. We conclude that there is a unique interest rate r∈(0,r*] that clears the market for bonds and that this interest rate is strictly lower than r*. Given r, it is straightforward to derive all the other variables in the steady state.

The interest rate r is an increasing function of B*/YT. To see this, compute the derivative dP/d(B*/YT) evaluated at the root  It has the sign of

It has the sign of  Since P is increasing around

Since P is increasing around  then

then  is a decreasing function of B*/YT. Therefore,

is a decreasing function of B*/YT. Therefore,  increases with B*/YT.

increases with B*/YT.

Finally, the ratio of related traded consumption cLT/cAT is given by the first-order condition (equation (5)) and is equal to βr=r/r*<1.

Assume now that the borrowing constraint does not bind. From the first-order conditions (equations (5) and (6)) when λ=0, we must have βr=1 in any symmetric steady state, that is, r=r*. Then, it is easy to compute all the other variables in the steady state, to check that the borrowing constraint indeed does not bind, and that

Derivation of Equation (20)

The first-order conditions with respect to At+1, Lt+1, and π t are:

The sum of the first-order conditions with respect to At+1 and Lt+1, together with the last one, gives γ t B=βrt+1Λt+1/2. This proves Equation (20).

The difference of the first-order conditions with respect to At+1 and Lt+1 gives

Derivation of Equation (21)

From the first-order condition with respect to λt+1, we have: κ t Lβrt+1v′(ct+1AT)=Δt+1[φ(Yt+1T+pt+1Yt+1N)−rt+1Lt+1] from which we can deduce that κ t L=0.

Consider the first-order conditions with respect to c t AT

and with respect to c t LT

To get an expression for γ t G, we first need to compute γ t A, γ t L, γ t N, and κ t A.

The first-order condition with respect to rt+1 is

In the closed economy, we have At+1=L+1. If in addition φ=0, we get At+1=Lt+1=0, so that κ t A=0.

The Lagrange multiplier γ t N is given by the first-order condition with respect to p t , together with (10):

Finally, from the first-order conditions (equations (A.2) and (A.3)), together with the Euler Equation (6), we can show that Λ t =λ t /ct+1AT.

We can now evaluate γ t G and Λ t in the closed economy with φ=0. In this case, we have At+1=Lt+1=B*t+1=0 and therefore π t =0. From the current account identity (equation (17)), and the budget constraints (equations (2) and (3)), we get c t AT=Y t T and c t LT=aY t T. The Euler Equation (5) implies that βrt+1=a(1+gt+1). From Equation (6), we get λt+1=1/(a2)−1. Therefore, Λ t =(1/(a2)−1)(1)/(Y t T). Then, we can iterate Equation (A.1) forward to get γ t A=−γ t L=−(1−a)/(2aY t T). From Equation (A.5), we get γ t N=(1+a)/(2aY t T). Then, Equation (A.2) yields γ t G=(1+a)/(2aY t T). Therefore,

which yields Equation (21).

Derivation of Equation (22)

By definition, J* is the left-hand side of Equation (20), evaluated at rt+1=r*=1/β, so we have:

Subtracting Equation (A.3) at t+1 from Equation (A.2) at t, and using the fact that c t AT=ct+1LT in the open economy, we obtain:

By iterating Equation (A.1) forward when βrt+1=1, and given that γ t A=−γ t L, we get γ t A=−γ t L=∑s≥1(−1)s(Λt+s)/(2). Then, Equation (A.4) in the open economy can be rewritten:

Injecting Equations (A.5) and (A.8) in Equation (A.7), and replacing γ t G−γt+1G in Equation (A.6), we obtain Equation (22).