Abstract

The following article reviews the recent regulatory efforts in defining systemic risk in the insurance sector and the designation of systemically important insurers. Although current evidence suggests that core insurance activities are unlikely to cause or propagate systemic risk, the characteristics and business models of insurance firms vary by country and might require a more nuanced examination, with a particular focus on non-traditional and/or non-insurance activities. The article also includes the assessment of identified vulnerabilities from liquidity risk in the context of the Bermuda market, which provides valuable insights into systemic risk analysis in the domestic context of an insurance market dominated by non-life underwriting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the wake of the global financial crisis, there has been increased focus on systemic risk as an essential element of macroprudential policy and surveillance (MPS).Footnote 1 MPS aims to limit, mitigate or reduce systemic risk, thereby minimising the incidence and impact of disruptions in the provision of key financial services due to an impairment of all or parts of the financial system that can have adverse consequences for the functioning of the real economy (and broader implications for economic growth).

The identification of SIFIs is a crucial element of systemic risk analysis within MPS. Systemic risk refers to individual or collective financial arrangements—both institutional and market-based—that could either lead directly to system-wide distress in the financial sector and/or significantly amplify its consequences (with adverse effects on other sectors, in particular, capital formation in the real economy). The potential emergence of systemic risk and its impact on financial stability is significantly influenced by institutions whose disorderly failure, because of their size, complexity and systemic interconnectedness, would cause significant disruption to the financial system and economic activity.Footnote 2 A material financial distress at such a systemically important financial institution (SIFI), related to its nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or the mix of its activities,Footnote 3 can adversely affect financial stability due to the spillover effects of their actions on the financial system and the wider economy.

Policy-makers have recognised the need for enhanced regulatory and supervisory requirements for SIFIs in response to concerns over the moral hazard risks arising from large and highly integrated financial institutions that are regarded as too important to fail. In 2009, the FSB mandated both the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) to develop a methodology to assess the systemic importance of banks and insurance firms, respectively. The commonly accepted definition of SIFIsFootnote 4 has placed also non-bank financial institutions squarely within the scope of any systemic risk regime, including systemically relevant insurance companies. Although the BCBSFootnote 5 has already designed an indicator-based approach for the identification of global systemically important banks, so-called “G-SIBs”, similar efforts are nearing completion for the identification of systemically relevant non-banking activities (with the most challenging policy agenda still lying ahead in the area of systemic risk within shadow banking). In July 2013, after one year of public consultation, the IAISFootnote 6—in coordination with the FSB—published its final version of an initial assessment methodology for the identification of globally active, systemically important insurance firms (G-SIIs) together with a draft proposal of policy measures for designated firms,Footnote 7 including enhanced supervision, effective recovery and resolution, and capital requirements. Most recently, the FSB,Footnote 8 in consultation with the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), also proposed assessment methodologies for identifying non-bank, non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions (NBNI G-SIFIs), which covers finance companies, market intermediaries (securities broker-dealers) and investment funds.

The designation of SIFIs in the insurance sector has attracted considerable attention. The weighted indicator-based approach for G-SIIs is similar in concept to that used to identify G-SIBs, but also introduces additional indicators that are germane to insurance activities. In addition, the IAIS has created working parties for the development of both basic capital requirements (BCR) for purposes of general loss absorbency (LA) and higher loss absorption (HLA) capacity requirements for G-SIIs by the end of 2014 and 2015, respectively, which are likely to be informed by G-SII assessment methodology. The increased supervisory focus on systemic risk has already elevated identification of systemically important activities to the level of standard insurance principles in 2011. The new ICP 24 (Macroprudential Surveillance and Insurance Supervision) charges supervisors with the monitoring of vulnerabilities in the financial system and underlying trends within the insurance sector, aimed at identifying and mitigating systemic risk that might negatively affect the risk profile of insurers.Footnote 9

This article reviews the past and current discussion on systemically relevant activities in the insurance industry and examines the plausibility of existing approaches in a theoretical and practical context. Any approach aimed at measuring systemic risk across different areas of financial activity consistently and effectively needs to be flexible enough to take into account that the various types of financial institutions perform different functions within the financial system. Although core principles used to determine systemic relevance should be applied universally, the designation of systemically important insurers would heed the distinct characteristics of insurance business models and the extent to which certain firms engage in activities that are, or could become, systemically relevant. In this regard, the article establishes a common understanding of whether some identified vulnerabilities from non-traditional and/or non-insurance (NTNI) activities (especially in the area of liquidity risk) are relevant to the (re)insurance sector in Bermuda for the identification of systemic risk—without proposing new prudential standards guiding their supervisory treatment.

The article is structured as follows. After highlighting the differences between the business models of banks and insurance companies, which influence the design and implementation of macroprudential tools to limit systemic risk, the article reviews the scope of systemically important activities in the insurance sector and the identification of systemically important insurance firms (Section “systemic risk measurement and its relevance in the insurance sector”). Based on industry proposals and supervisory discussions that informed the current consultation on G-SIIs, the subsequent section examines whether some insurance activities that have generally been considered systemically relevant on a global scale also pose similar risks for the (re)insurance industry in Bermuda, which is largely focused on non-life underwriting activities. The latter section introduces the proposed assessment methodology for G-SIIs and provides initial considerations regarding its implications for the consistent treatment of systemic risk in financial sector regulation. The final section concludes by highlighting existing challenges and provides a forward-looking perspective on supervisory initiatives in this regard.

Systemic risk measurement and its relevance in the insurance sector

General principles of systemic risk measurement

Despite many methodological and empirical approaches aimed at the identification and measurement of systemic risk, there is still no consistent theory of regulating and supervising systemically important activity. Ideally, systemic risk measures should support, or be linked to, MPS objectives, by providing information on the build-up of system-wide vulnerabilities in both the time and cross-sectional dimensions with an acceptable level of accuracy and forecasting power for financial instability.

The existing approaches can be broadly distinguished based on their conceptual underpinnings regarding the sources and risk transmission that would render a financial institution systemically relevant. There are three general approaches: (i) a particular activity causes a firm to fail and imposes marginal distress on the system due to the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration or connectedness of its activities with other financial institutions (“contribution approach”), or a firm either (ii) absorbs (“participation approach”) or (iii) amplifies the shock (“participation-contribution approach”) from the scope and/or magnitude of impact of one or more negative shocks to commonly held exposures to a particular sector, country, interest rate and/or currency due to their types of business models, risk profiles and/or performance characteristics. Table 1 summarises the distinguishing features of these approaches and illustrates how they are reflective of different policy objectives regarding the broader effect of systemic risk on financial stability.

There are several methodological proposals that coexist in a loose manner. The growing literature on systemic risk measurement is the result of greater demand placed on the ability to develop a better understanding of the interlinkages between firms and system-wide vulnerabilities to risks as a result of the (assumed) collective behaviour under common distress. Most of the prominent institution-level measurement approaches, such as CoVaR,Footnote 10 Footnote 11 CoRisk,Footnote 12 Systemic Expected Shortfall (SES),Footnote 13 , Footnote 14 Granger Causality,Footnote 15 SRISKFootnote 16 and Systemic Contingent Claims Analysis,Footnote 17 have focused on the “contribution approach” by including an implicit or explicit treatment of statistical dependence in determining the role of SIFIs in causing material distress within a defined system.Footnote 18

The distinction of measurement approaches also reflects varying channels of risk transmission, with banks and non-bank financial institutions causing systemic risk differently. Although banks are prone to contribute to systemic risk from individual failures that propagate material financial distress or activities via intra-and inter-sectoral linkages to other institutions and markets (based on direct exposures via lending and investment) and threaten to cause disruptions to the functioning of the financial sector infrastructure due to a lack of substitutability (“contribution approach”), non-bank financial institutions tend to be more affected by their common exposures to asset price shocks that challenge the overall resilience of the sector (“participation approach”).

Systemic risk measurement for the insurance sector

Although several of these core principles determining systemic relevance apply universally, any assessment methodology would need to be flexible enough to take into account of the fact that the various types of financial institutions perform different functions within the financial system. Understanding the differences in business models, behavioural characteristics under stress, and their structural implications for the financial sector are fundamental to the qualified assessment of their influence on potential transmission channels (as mentioned above) and, by extension, affect the real economy. However, they should not inhibit approaches aimed at comprehensively measuring systemic relevance, covering all types of financial institutions, to the extent that the timely identification of a build-up of systemic risk might be compromised.

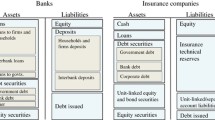

The different nature of risk taking of banks and insurance companies suggests limited usefulness of existing methods to identify systemic risk. Established (bank-focused) approaches to systemic risk are instructive but require careful assessment as to their adaptability for the design of an effective framework for the insurance sector.Footnote 19 Although insurance companies share some similarities with banks, such as the management of cash flows over different risk horizons to satisfy payment claims arising from providing financial services, their leverage does not result from liquidity or maturity transformation and is hardly susceptible to the cyclicality of funding sources. Banks leverage their asset base by incurring short-term liabilities (deposits and/or debt securities) to fund their lending and investment business.Footnote 20 In contrast, the leverage of insurance companies is client-driven, since it reflects the desired collateralisation of future payment obligations (via technical provisions) and, thus, is endogenous to the underwriting performance (rather than a strategic business decision regarding risk appetite in financial intermediation).Footnote 21

Most supervisory concerns about insurance activities tend to arise from liquidity rather than solvency risk; however, insurers aim to closely match the duration of assets and liabilities. Insurance companies pursue a predominantly liability-driven investment approach to ensure that they can meet their policyholder obligations arising from such underwriting risk (especially for non-life insurance firms), which is largely idiosyncratic and generally independent of the economic cycle. Cash inflows from unearned premiums are invested such that payments of future (unsure) claims can be made at all times, which explains why asset–liability matching plays such a critical part of an insurer’s profitability, especially during adverse economic conditions that might negatively affect investments over prolonged periods of time. Claims can normally be paid via the sale of liquid assets that generate commensurate cash inflows (as opposed to traditional financial intermediation, which involves maturity transformation). The pre-paid funding model (with the possibility of continued collection of premiums even in a recovery or resolution phase), the longer duration of the claims process and penalties for early surrenders of life insurance policies make insurers generally less susceptible to liquidity runs and spillover effects from interlinkages during times of systemic stress. Thus, insurers can be insolvent (or insufficiently solvent) and still remain liquid due to the long-term nature of the business model.

Therefore, institutional failures of insurers have arguably a different impact on the financial system than those in the banking sector, and the way in which they might create and/or propagate systemic risk due to key differences between banks and insurance companies:Footnote 22

-

Risk types and links to the economy. Insurance companies are exposed to risks commonly found in other financial institutions, including credit risk, operational risk and market risks related to equity investments as well as adverse movements in interest rates and exchange rates, all of which are highly correlated with changes in economic conditions; however, risks from underwriting (e.g. mortality, morbidity, property and liability risks) are generally independent of the economic cycle, which allows them to realise additional diversification gains (through investment in inversely related assets, risk pooling or risk sharing via reinsurance), whereas banks, by the acceptance of deposits and granting of loans, might find it more difficult to reduce their credit risk (from lending) or liquidity risk (from the maturity mismatch in borrowing short and lending long).

-

Integration in financial sector infrastructure. As insurance firms are not part of payments or clearing systems essential to economic activity (which they access but do not have responsibility for organising), they tend to hold only limited direct intra-system claims and liabilities and exhibit relatively low levels of interconnectedness with the rest of the financial system both domestically and across national boundaries. Even though large insurance groups have a global presence, they also do not provide essential financial market utilities and are generally less integrated in the financial sector infrastructure than banks. Thus, individual failure does not have the same negative systemic impact as the failure of a bank would. In fact, failures take place over an extended time period that allows for orderly planning as part of stable processes that do not lead to destabilising runs. Also, many less complex insurance products limit systemic risk from the uniqueness of insurance capacity offered by a failing institution. However, the interlinkages between insurers, banks and other financial institutions may increase in the future through products, markets and conglomerates, which warrants enhancements to supervisory processes, combined with stronger risk management and flexible approaches to resolvability in order to minimise adverse externalities.

-

Risk transfer and absorption. The risk-absorbing capacity of insurance firms—together with their different business characteristics from banks—is likely to reduce systemic risk in general (see Table 1). As opposed to risk transfer of bank assets, insurance risks are kept in general on the balance sheet, which mitigates the risk of moral hazard generated by the separation of origination and distribution activities through securitisation. Two types of risk transfer activities are most important in this regard—reinsurance and derivatives transactions. Although the trading of derivatives for hedging purposes and the underwriting of reinsurance contracts are generally considered traditional functions, all non-hedging/non hedge replicating derivatives and the issuance of CDS protection are deemed non-insurance activities in the absence of insurable interest.Footnote 23 , Footnote 24 The reinsurance of primary underwriters and the acceptance of ceded insurance risk between reinsurers (i.e. retrocession) involve only a partial transfer of risk, with most risk staying on the ceding (re)insurer’s balance sheet. Since reinsurance improves the diversification of risks over different business lines and across national boundaries, it also facilitates the optimal allocation of capital.

-

Funding structure. In the absence of maturity transformation, consumer or commercial credit, or transaction clearing services, insurers exhibit a liquidity position that is less influenced by external funding conditions due to strong operating cash flows via upfront premium payments together with a longer-term investment horizon compared with other types of financial institutions. Insurance operations are deemed to be stabilisers to the financial system through a so-called “inverted production cycle”, that is, firms are funded by reserves (through upfront premium payments), resulting in stable cash flows to the insurer (unlike in the banking model). Even though insurers are only partially self-funded (as the bulk of their funding stems from reserves), reserves are usually longer term than common funding sources (interbank or wholesale market liabilities) of commercial banks.

-

Characteristic of cash outflows. Also most cash outflows of insurance companies are determined by the timing and administration of policyholder claims (rather than debt payments to creditors). The payment of insurance claims differs significantly from the execution of margin calls and/or the satisfaction of depositor claims in the banking sector. Insurers are not predisposed to sudden cash withdrawals, as most insurance liabilities are not redeemable on demand by policyholders (like bank deposits) and require a triggering event, whose probability is independent of general economic conditions. Even though some forms of life insurance may be viewed as savings products, most contracts have tax and contractual disincentives for policyholders to surrender the insurance policies before its contractual maturity (i.e. insurance reserves are not instantaneously “puttable” like deposits). Conversely, where reserves are “puttable”, the policyholder bears the investment risk (unit-linked, separate accounts).

Thus, the distinct characteristics of the insurance business model suggest a lower susceptibility to cause (or amplify) systemic risk. Insurance companies pursuing traditional underwriting activities (defined by insurable interest subject to insurance accounting and regulations) are generally considered to represent a lower level of systemic risk than banks, mainly because of the different character of their liabilities and the lower degree of interconnectedness to other financial institutions and capital markets.

However, non-core underwriting and investment activities—with no direct connection to the traditional business model—might be subject to systemic risk considerations. Most of these systemically relevant activities tend to amplify rather than induce systemic risk (in keeping with the “participation approach” (see Table 1)) and typically arise on the group level in the context of changing business models. For instance, insurance companies have extended their underwriting activities to non-traditional features, such as different types of financial lines (including mortgage guarantee, financial guarantee, fidelity and surety) and reinsurance contracts with modified risk transfer, which can materially affect the risk profile of contracts. Moreover, traditional funding activities have become mixed with non-traditional activities, such as extensive securities lending and liquidity swaps. These non-core activities (rather than specific institutional arrangements) as sources of systemic risk require a nuanced consideration of the relative importance of the various channels of systemic risk transmission, such as connectedness, substitutability and the timing of payment/asset liquidation, with a greater emphasis on systemic risk participation, with large shocks to common exposures affecting the overall functioning of the sector.

Although traditional insurance activities have not contributed to systemic risk during the financial crisis, the interlinkages between insurers on the one hand and financial markets, banks, other insurance companies as well as the real sector (non-financial corporations and households) on the otherFootnote 25 (Figure 1) may increase in the future through products, markets and conglomerates. While the long-term nature of many insurance business models with a low “puttability” of reserves implies a high capacity to absorb shocks, it also puts a premium on the reliability of actuarial methods, especially during times of stress when valuation models might fail to fully reflect potential downside risks and distort the true value of both assets and liabilities.

There are also potential sources of systemic risk associated with long-term trends that could negatively affect the insurance sector, such as climate change, the secular decline of real interest rates and longevity. Even though these risks impact primarily the solvency condition of firms (which is less relevant for systemic risk concerns arising from illiquidity), if not addressed and mitigated in time (especially in areas of homogenous firm behaviour), could potentially compromise the long-term viability of certain lines of business.

Identifying systemically relevant insurance activities and systemically important insurance companies

Initial regulatory proposals and industry suggestions

At the end of 2009, the Financial Stability Committee (FSC) of the IAISFootnote 26 started first consultations with the insurance industry towards establishing a globally binding assessment framework for systemically important insurance companies. At the time, the development of systemic risk measurement in general, and for the insurance sector in particular, was still in its infancy. Given the limited experience in insurance-specific macroprudential surveillance activities in relation to systemic risk at both domestic and global levels,Footnote 27 the IAIS initially followed the rationale of identifying SIFIs in the banking sector, which defines several quantitative indicators of systemically relevant activities. These systemic risk indicators—cross-jurisdictional activity, size, interconnectedness, substitutability and timing—would all need to be triggered for a determination of systemic risk relevance—after considering the impact of all aggravating and mitigating factors, such as internal risk controls, posted collateral and the scope of supervisory oversight on the assessment of systemic relevance.

In addition, the IAISFootnote 28 viewed the complexity of insurance companies (and their transactions) as an important criterion in the determination of systemic risk, which involves their resolvability as a qualitative determinant of systemic relevance. Thus, the likelihood of an insurance company to be resolved or restructured in an orderly procedure if it were to fail without causing a systemic event was taken as an additional consideration with regard to operational and legal complexity giving rise to systemic importance.Footnote 29

In response to the early efforts of the IAIS of relating systemic importance to institutional characteristics, The Geneva AssociationFootnote 30 proposed a shift of focus away from the risk indicator-based approach towards particular activities that could cause systemic risk in the insurance sector and the financial system at large. It suggested an activity-based approach of identifying potentially systemically risky activities (pSRA), with a particular focus on derivatives trading and short-term liquidity risk management.

Discussion of industry-suggested systemic risk indicators

In 2011, the insurance industry proposed the adoption of several broad risk indicators for the evaluation of non-core insurance activities—financial guarantees, derivatives underwriting—and short-term liquidity mismanagement as sources of systemic relevance. In furtherance of the activity-based approach of identifying potentially pSRA, The Geneva Association30 , Footnote 31 suggested several indicator-based metrics that combined these insurance activities with the different channels of risk transmission—size, interconnectedness, substitutability and timing (see Table 2), which were identified in earlier attempts at specifying systemically important insurance companies consistent with the general principles established by the IAIS.28 Although the proposed risk indicators avoid complex valuation models, they are based on static and microprudential measures, and, thus, assess the cross-sectional dimension of systemic risk only from a supervisory perspective without considering the market dynamics of derivatives trading and liquidity management. For instance, short-term funding activities would be most suitably addressed by liquidity risk indicators that can qualify the connectedness via exposures to particular counterparties (possibly conditional on their creditworthiness).

Adaptation and suggested enhancements of industry-suggested systemic risk indicators for liquidity risk

In this section, we examine whether insurance activities that have generally been considered systemically relevant on a global scale, such as short-term liquidity mismanagement,Footnote 32 also pose similar risks for (re)insurers sector in Bermuda. In particular, we investigate the general usefulness of the liquidity risk indicators according to the activity-based assessment method put forth by The Geneva Association and propose suggestions for their modification and, where appropriate, suitable enhancements consistent with the overall concept of identifying systemically important insurance activities suggested by the IAIS in the course of developing the G-SII assessment methodology. Thus, our analysis also provides valuable insights into the relevance of systemic risk indicators within an insurance market that is largely focused on non-life underwriting activities outside the home jurisdiction.

Discussion of liquidity risk indicator

The transmission channels of relative size, connectedness and substitutability serve as a starting point for analysing short-term funding risks from illiquid asset holdings as a frequently mentioned source of systemic riskFootnote 33 as the basis for an empirical application using prudential data of the Bermuda insurance sector.

-

Size: We define the size indicator of liquidity risk as liquid assets to probable maximum losses (PML) and actual attritional losses (or alternatively, only net PML or net losses and loss expense provisions as scaling factors). This potential funding shortfall of liquid assets relative to expected (actuarially-derived) cash outflows from loss claims would need to be scaled relative to a firm-specific measure of liquidity and/or solvency, such as total liabilities (which generates the liquidity ratio). In addition, the cross-sectional variation of this indicator would also require qualifying the identified liquidity shortfall based on the economic significance of liquid assets of the firm relative to the maximum potential liquidity in the system, that is, the total liquid assets reported by all sample firms,

for a pre-specified threshold.

-

Connectedness: In the absence of firm-by-firm data on lending and borrowing relationships within and across the sector, the distribution of short-term funding risk (and the degree to which interlinkages between firms could cause systemic risk from liquidity shortfall) can be approximated using the concentration of liquid assets to different scaling factors (such as net PML and actual attritional losses), possibly in combination with the concentration of funding sources of individual entities. The concentration measure is defined based on the normalised Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) in percentage terms,Footnote 34

where

which represents the “market share” of liquidity surplus/shortfall for N number of firms, measured as the ratio between the difference of liquid asset and PML and actual attritional losses of firm i (numerator), and the sum of liquidity surplus/shortfall for all firms in the sample (i.e. all Class 4 or Class 3B insurance companies). The specification of  in Eq. (3) above reflects a shifted distribution of liquidity surplus/shortfalls to generate positive values only.

in Eq. (3) above reflects a shifted distribution of liquidity surplus/shortfalls to generate positive values only.

-

Substitutability: We measure the degree of substitutability as the contribution of individual liquidity needs to the concentration of overall liquidity risk by calculating the degree to which each firm j with liquidity shortfall (measured as the difference of liquid asset and PML and actual attritional losses) contributes to the asymmetry of the concentration measure HHI* N of overall liquidity risk (see Eq. (2) above). More specifically, the “excess contribution” of each firm is measured either as its share of the total statistical variance,

or its contribution relative to the average contribution of each firm,

which should be 1/N and zero, respectively, if the liquidity surpluses/shortfalls were homogenously distributed (i.e. all firms have—on average—equal (identical) liquidity surpluses/shortfalls) and, thus, liquidity risk is completely symmetric, so that  for firm i and

for firm i and

where V N is the statistical varianceFootnote 35

Alternatively, we define the “marginal contribution” of this firm to the normalised HHI measure (see Eq. (1) above) as

where j∉N.

All risk indicators would ideally be extended to fully capture the different types of risk transmission and their impact on financial stability both within a particular country and across national boundaries (“cross-sectional dimension”). Individual risk indicators could be modified to reflect the total effect of any firm (beyond the magnitude of liquidity shortfall as the distinguishing feature) and/or the joint effect of multiple firms on system-wide liquidity risk (and extent to which short-term funding activities pose systemic risk).Footnote 36

Also the variability of system-wide vulnerabilities to common adverse shocks needs to be addressed (“time-varying dimension”). In the case of liquidity risk from short-term funding activities, a simple or weighted average over a pre-defined risk horizon could be calculated as a “through-the-cycle” measure, subject to the frequency of statutory reporting.Footnote 37

Empirical findings for large commercial (re)insurers (Class 4 and 3B) in Bermuda

We obtained prudential information from the annual Bermuda Solvency Capital Requirement (BSCR) filings of 45 registered Class 4 and 3B commercial (re)insurers. The BSCR represents a principles-based regulatory regime that is geared towards understanding the risk profile or characteristics of Bermuda (re)insurers consistent with similar approaches in other jurisdictions. It was established under the Insurance (Prudential Standards) (Class 4 and 3B Solvency Requirement) Rules 2008 (the “Rules”) by the Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) in combination with the Guidance Note No. 17 on Commercial Insurer Risk Assessment. Together with the Insurance Act 1978, Insurance Returns and Solvency Regulations 1980, Insurance Accounts Regulations 1980 (which were amended in 2008) and the Insurance Code of Conduct 2010, it forms the regulatory regime for the (re)insurance sector in Bermuda.Footnote 38

Over the sample period between 2007 and 2011, we found that large commercial (re)insurance companies do not seem vulnerable to short-term liquidity risk, which has been deemed systemically important in current policy proposals. More specifically, our findings suggest that:

-

Despite a record level of insured losses in 2011, liquidity positions of firms remained broadly resilient. Even though liquidity levels have remained stable for most of the sample period, above-average claims activity during 2011 resulted in a significant decline, albeit from a very high starting level. Since our sample comprises (re)insurance companies with largely short-tailed property and casualty (P&C) exposure, however, there are no callable short-term liabilities from surrenders by policy holders (but rather external events). Thus, liquidity risk would arise primarily from asset-liability mismatches (and short-term liquidity mismanagement).

-

Firms held high liquidity buffers well above prudential requirements to ensure a high claims paying ability relative to net probable maximum losses (PML) and attritional losses (i.e. losses other than those related to major catastrophes or exposures, which can impact reserves up to seven or eight years (sometimes more) after a loss event) as a measure of worst-case short-term cash flow demands.Footnote 39 As a general indicator of liquidity (and the relative size of outstanding contracts), the ratio of liquid assets to net PML declined only by 8.4 per cent during the financial crisis between 2007 and 2010, and stood at 743 per cent at end-2011 (see Table 3). However, a considerable decline of liquid assets relative to changes in net loss and loss expense provisions highlights that low premium levels over the last three years and record losses in 2011 have not only put greater focus on reserve adequacy but also adversely affected system-wide liquidity.

Table 3 Bermuda Class 4 and 3B (re)insurance Firms—Liquidity conditions, 2007–2011 -

Insurers with potential liquidity shortfall under stress did not seem to have systemic relevance. Although four insurers did not meet the liquidity ratio and show a disproportionate contribution to system-wide liquidity risk at end-2011, their economic significance was very small, with results indicating a low probability of material financial distress within the sector caused by an adverse short-term funding scenario (see Table 4).Footnote 40 More specifically, at end-2011, we find that these firms represent barely more than 2.4 per cent of aggregate liquid assets in the sample, but increase the concentration of liquidity risk by more than 31 per cent.

Table 4 Bermuda class 4 and 3B (re)insurance firms—Level and concentration of liquidity risk, 2007–2011

However, further analysis of institutional linkages and concentration of both investments and liabilities is needed for a more comprehensive assessment of spillover effects from liquidity risk, which can help inform the forward-looking assessment of system-wide vulnerabilities.Footnote 41

Current assessment methodology for systemically important insurance companies (G-SIIs)

Policy discussions and industry consultations helped narrow the supervisory perspective on the systemic relevance of insurance activities in the process of developing a viable assessment methodology. The IAIS converged to the industry view that traditional insurance business—with the exception of general vulnerabilities to common asset price, disruptions to market functioning and cyclical pressures—is unlikely to generate and/or amplify systemic risk within the financial system (and the real economy).Footnote 42 Since most insurance techniques rest on the pooling of a large number of ideally uncorrelated risks,Footnote 43 an increase of a well-diversified underwriting portfolio lowers unexpected losses as the probability of very large losses (relative to the size of the portfolio) decreases. As a result, the IAIS clarified its original conceptual approach to systemic risk by acknowledging that primarily certain (non-core) activities—if conducted on a large scale without adequate prudential oversight—rather than institutional fragility per se could pose system-wide vulnerabilities.27

On 18 July 2013, the IAISFootnote 44 published its final version of the initial assessment methodology, which comprises five categories of risk drivers that reflect the relative importance of each indicator for the assessment of systemic relevance of insurers (size, interconnectedness, substitutability, NTNI activities and global activity). Within these five categories are a total of 20 indicators, including intra-financial assets and liabilities, gross notional amount of derivatives, Level 3 assets, non-policyholder liabilities and non-insurance revenues, derivatives trading, short-term funding, liability liquidity, and variable insurance products with minimum guarantees.Footnote 45 The IAIS has assigned weightings as follows: 45 per cent to NTNI activities, 40 per cent to interconnectedness, 5 per cent to substitutability; 5 per cent to size and 5 per cent to global activity. Within all five categories, equal weight is given to each indicator. Each insurer receives one score for each of the indicators, which are then weighted and summed up to form the overall individual score.Footnote 46 , Footnote 47

In its assessment methodology the IAIS acknowledges that the systemic relevance of insurance companies is generally different (and possibly smaller) than that of banks, but maintains the view that the failure of an insurer has the potential to pose risks to financial stability. In particular, interconnectedness and NTNI activities of firms are deemed significant transmission channels for the determination of the systemic relevance of insurers, while size and global activity are deemed less important (relative to other risk indicators within the assessment methodology. Although traditional insurance activities benefit from risk pooling and lower funding risk (as a result of predominantly liability-driven investments, extended pay-out periods for claims, and non-cyclical insurance events), NTNI activities (especially if conducted with multiple counterparties) can be more vulnerable to financial market developments and may therefore be more likely to amplify, or contribute to, systemic risk from general asset price shocks.Footnote 48 Also differences in business models, behavioural characteristics under stress and their structural implications for the financial sector influence potential transmission channels for systemic risk. Thus, the IAIS combines the application of the assessment approach with a supervisory judgement and validation process.Footnote 49

In 2013, the FSB,Footnote 50 in consultation with the IAIS and national authorities, designated nine insurance groups as G-SIIs, using a revised version of the initial assessment methodology developed by the IAIS.Footnote 51 , Footnote 52 , Footnote 53 The assessment methodology was based on a weighted indicator approach similar to the one developed by the Basel Committee to identify G-SIBs5 and reflects the specific nature of the insurance sector,27 which has influenced the selection, grouping and weights assigned to certain indicators. Even though the assessment framework also applies to reinsurance companies, the potential G-SII designation of a subset of internationally active reinsurers has been delayed.Footnote 54

Although both G-SII and G-SIB assessment methodologies attribute considerable importance to the interlinkages of firms and the international scope of business activities, there are some salient differences (see Table 5). In contrast to the G-SIB approach, the IAIS’ indicator-based assessment methodology for G-SIIs consisting of five categories of risk drivers (i) integrates the “complexity” category (which includes derivatives liabilities and Level 3 assets) into an expanded “interconnectedness” category, (ii) introduces a separate (and heavily weighted) category for NTNI activities (which includes several liquidity risk elements that the G-SIB methodology addressed in its interconnectedness category), and (iii) defines global activities as significant foreign business activities (rather than cross-border claims and liabilities). The methodology is focused on the relative importance of each firm within an indicator-based assessment framework without passing judgement as to the scope and quantum of systemic risk posed by the insurance sector in aggregate (or, collectively by selected sample firms). Like the approach adopted by the Basel Committee, the IAIS does not unify the conjunctural dimensions of systemic risk (as a result of vulnerabilities arising from both cross-sectional and time-varying risk indicators) in its assessment methodology of systemic relevance.

The implementation of the assessment methodology represents the first step towards the adoption of several policy measures associated with the designation of G-SIIs. The three policy implications flowing from the SIFI assessment involve the improvement of the regulation, supervision and resolution of SIFIs in the following areas: (i) higher loss absorbency (HLA) through additional capital chargesFootnote 55; (ii) more intensive supervision, stronger supervisory mandates and resources, higher supervisory expectations, enhanced reporting, including group-wide supervision; and (iii) the requirement of recovery and resolution plans (RRPs) for designated insurers, including resolution regimes and cross-border mechanisms, consistent with the key attributes on the resolution of systemic insurance groups.Footnote 56 As a foundation for HLA requirements for G-SIIs, the IAIS is also developing BCR to apply to all group activities, including non-insurance subsidiaries, to be finalised by the time of the G20 Summit in 2014Footnote 57 before commencing a public consultation on the implementation details for HLA by end-2015.Footnote 58 , Footnote 59

Also national supervisors have begun to define their own criteria for the designation of non-bank SIFIs, which includes insurance companies. Changes to national insurance regulations aimed at the heightened supervision of systemically important institutions have paralleled efforts by the IAIS to define systemic risk in the insurance sector. For instance, in the United States, the FSOC3 determines the systemic importance of nonbank financial institutions (including insurance companies) that could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability by means of a three-stage assessment process.Footnote 60 The first stage (“Stage 1”) establishes a triage prior to the testing for potential systemic risk, which delimits the universe of nonbank financial companies to be subject to further evaluation (as target group), based on six uniform quantitative thresholds. Subsequent testing for potential systemic risk is carried out in Stages 2 and 3 after companies that did not meet the selection criteria in Stage 1 have been excluded. In addition to the four more general aspects of systemic relevance (see Table 5), which are also included in the IAIS’ G-SII methodology, the first stage of the determination process includes two additional high-level microprudential indicators (leverage and liquidity risk/maturity mismatch) and the assessment of the level of existing regulatory scrutiny to its “determination process”. The FSOC’s national framework for determining systemic relevance also includes the assessment of existing supervision. Such a firm-specific element (of greater “customisation”) would include not only the degree to which regulatory requirements are already applicable to a particular non-bank financial institution, but also the relative effectiveness of new regulatory requirements, including enhancements to resolution regimes and the enforcement of recovery plans.

Given the wide range of different national regulations and industry structures, effective supervisory coordination is essential to a consistent and meaningful assessment of systemically relevant insurance activities both within and across national borders and different industry sectors. In particular, the identification of SIFIs is closely associated with the establishment of a suitable reference system, which defines the extent to which certain firms engage in activities that are, or could become, systemically relevant domestically or abroad. Any unintentional differences in the treatment of systemically relevant insurance firms, however, could undermine the quality and credibility of designations from different sources.Footnote 61 This could happen, for instance, in cases when an international designation of an insurer is not recognised by national prudential standards in some of its most significant markets and/or systemic importance might not be significant to warrant the designation of G-SIIs but could affect financial systems of multiple countries within a region. Figure 2 illustrates how overlapping SIFI assessment methodologies of globally active insurance companies can arise, especially across different sectors, if a conglomerate includes a designated insurer but also a large bank subject to global/domestic/both SIFI designations. Attendant inconsistencies could also be compounded by the fact that some insurance groups also include banking operations that might be subject to their own macroprudential treatment—both domestically and globally.

Potential overlaps between global and domestic SIFI methodologies.Note: As an example, the figure illustrates the area of potential overlap between the IAIS and FSOC methodologies regarding the identification of G-SIIs that are also deemed systemically important for the financial sector in the United States. “G-SIB”=globally active, systemically important bank, “G-SII”=globally active, systemically important insurance firm and “D-SII”=domestic systemically important insurance firm. Source: Author.

Conclusion

In this article, we found that the current development of risk measures for the prudential assessment of G-SIIs—based on both supervisory guidance and industry level feedback—has resulted in a comprehensive assessment methodology that adequately reflects the identified scope of systemically relevant insurance activities. However, further work might be needed to enhance the consistency and effectiveness of the final version of the initial assessment methodology for G-SIIs with regard to similar efforts on a national level (as well as internationally in other sectors, such as banking, where the SIFI agenda is more advanced) in areas where adverse effects from the interaction between insurance and banking activities are most likely to manifest themselves in times of stress. The interlinkages between insurers, banks and other financial institutions may increase in the future through products, markets and organisational arrangements, which warrants enhancements to supervisory processes, combined with stronger risk management and flexible approaches to resolvability. Thus, an integrated and comprehensive systemic risk assessment supporting financial stability analysis would ideally be based on a common framework for banking, insurance and other financial activities. This would ideally be achieved by means of an in-depth cross-sectoral analysis of the three global assessment approaches (G-SIB, G-SII and NBNI G-SIFI) in areas of common risk drivers, such as derivative trading, funding sources, and intra-financial assets and liabilities.

We also examined the relevance of current diagnostics from a national perspective by investigating their impact on the (re)insurance industry in Bermuda. In reference to suggestions that liquidity management could become sources of systemic risk, we found that international insurance companies registered in Bermuda show little susceptibility to short-term funding risks and contingent liabilities from financial guarantees. Further research is needed based on an enhanced understanding of the high degree of connectedness between insurance and reinsurance firms, spillover effects from within and outside the insurance sector, and the concentration of both funding sources and potential claims impacting on the propensity of reserve depletion.

Although the progress to date suggests a practical and objective identification of systemically relevant insurance activities, the current assessment of G-SIIs is bound to unify the conjunctural dimensions of systemic risk (as a result of vulnerabilities arising from both cross-sectional and time-varying risk indicators). By incorporating supervisory judgement and validation in the G-SII assessment, the IAIS has already acknowledged the critical role of mitigating factors associated with business models and structural aspects that affect the resilience of the entire insurance sector (or parts thereof). Further work could include (i) a more nuanced assessment of substitutability and interconnectedness, with a focus on how varying channels of risk transmission that cause spillover/contagion, (ii) the statistical stability of assessment methodologies for the designation of G-SIIs, and (iii) the potential reconciliation of risk indicators with other assessment methodologies for G-SIBs and NBNI G-SIFIs, which would help mitigate the potential for regulatory arbitrage within insurance groups.

Notes

See BIS (2011) and IMF (2011b) for an overview of current theoretical and empirical work on macroprudential policy and regulation, IMF (2013) for the latest guidance on macroprudential policy, and IAIS (2013d) with reference to MPS for insurance. In a recent progress report to the G20 (FSB/IMF/BIS, 2011b), which followed an earlier update on macroprudential policies (FSB/IMF/BIS, 2011a), the FSB takes stock of the development of governance structures that facilitate the identification and monitoring of systemic risk. See also IMF (2011a) for more insights on the governance issues surrounding macroprudential policies and IMF (2011a) for a more empirically focused review of macroprudential surveillance.

BCBS (2011, 2013).

IAIS (2012c, 2013c).

IAIS (2012a, 2013c).

Note that this term represents a conditional probability measure based on a threshold defined by the “value-at-risk” (VaR).

As well as extensions thereof, such as the distress insurance premium (DIP) by Huang et al. (2009, 2010).

For a more comprehensive summary of important systemic risk models, see Jobst (2013).

However, given the scarcity of sufficiently long-term assets, insurers often tend to have a negative duration gap (“short-long mismatch”) whereas the opposite applies to banking (“long-short mismatch”).

Moreover, insurance leverage trends to increase after a large claim due to higher technical provisions and lower equity (which contrasts with rising leverage as a sign of risk build-up in the banking sector).

See Geneva Association (2010a, 2010b, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c, 2012a) and IAIS (2010b, 2011a, 2012b) for a thorough review of the possible systemic relevance of insurance activities.

The IAIS (2011a) defines insurable interest as “an interest in a person or a good that will support the issuance of an insurance policy; an interest in the survival of the insured or in the preservation of the good that is insured. […] Financial derivatives are not considered insurance for regulatory purposes”.

However, established resolution regimes for insurers can be effective in limiting the impact of individual failure on policyholders (and ultimately its implications for fiscal policy).

See also Liedtke (2011).

The asterix indicates the HHI in its normalised form.

If the number of firms in the market is held constant, then a higher variance due to greater asymmetry of liquidity risk would result in a higher index value (Brown and Warren-Boulton, 1988).

The insurance classification scheme categorises large commercial insurance companies into three main groups—Class 4, Class 3B and 3A insurers (BMA, 2008; 2012a, 2012b). The Class 4 insurance category comprises (re)insurers capitalised at a minimum of US$100 million underwriting direct excess liability and/or property catastrophe reinsurance risk. Class 3B firms are large commercial insurers whose percentage of unrelated business represents 50 per cent or more of net premiums written or loss and loss expense provisions (and/or where the unrelated business net premiums are more than US$50 million). Since only Class 4 and 3B insurance companies were subject to the standardised solvency assessment under the BSCR framework until end-2010, the empirical analysis excludes Class 3A insurers, and, thus, covers only large commercial (re)insurers.

Although the BMA uses this measure for conservatism on account of uncertainty of contents, attritional losses arising from catastrophe exposure contracts may already be reflected in the net PML.

The liquidity ratio is calculated using total liquid assets to total liabilities. At end-2011, four companies scored below the 100 per cent threshold, which indicates some potential liquidity need if an insurer would have to immediately settle all callable insurance obligations. However, these results might overstate the actual funding shortfall over a short-term horizon due to limited information on the exact contractual maturity of potential cash outflows for positions callable within three months—the commonly assumed time period for net cash flow stress tests.

Bermuda was not identified as a jurisdiction with a systemically important financial sector for purposes of the IMF’s determination of a mandatory completion of the Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) every five years (IMF, 2010). Moreover, as part of an initiative to encourage the adherence by all countries and jurisdictions to regulatory and supervisory standards on international cooperation and information exchange, the FSB (2011b) designated Bermuda as a jurisdiction “demonstrating sufficiently strong adherence”.

Candidate firms for the potential designation as G-SIIs would need to satisfy two eligibility thresholds related to size and global activity. Based on end-2011 values, insurance companies would have to generate 5 per cent or more of gross written premium abroad and report total asset value of US$60 billion or more at the end of the fiscal year. Alternatively, firms can also be considered based on supervisory judgement.

A set of prudential and market data are used for the calculation of the indicators (e.g. total assets and total revenues are used for the Size indicator).

Paragraphs 35 and 36 of the published assessment methodology describe the procedure used to calculate the score of each indicator as follows: “For each insurer, the score for a particular indicator is calculated by dividing the individual insurer amount by the aggregate amount summed across all insurers in the sample. When an indicator consists of a combination of sub-indicators, the same calculation will be done for each sub-indicator; the results will be averaged to reach the score for the indicator overall. The score is weighted by the indicator weighting within each category. Then, all the weighted scores are added” (IAIS, 2013a, p. 20). For example, a hypothetical simplified Size indicator for a sample of three insurers, “Insurer A” (total assets=US$300), “Insurer B” (total assets=US$100) and “Insurer C” (total assets=US$400), would result in the following individual scores: Insurer A=300/800=0.375, Insurer B=0.125 and Insurer C=0.5 so that A+B+C=1.0. Subsequently, the individual scores of the 20 indicators are weighted, and then aggregated to obtain an overall score for each insurer. Note that current version the indicator-based assessment approach does not adjust for the differences in individual due to a different number of insurers being engaged in the activities that are measured by a particular indicator. As a result, insurers that are not in a position to engage in such activity (i.e. insurers not licensed or authorised to conduct the activity) are not excluded from the calculation of individual scores, which results in a disproportionately higher score due to sample bias. A possible solution to this problem could be an adjustment procedure. If certain indicators are relevant only for a sample n<N firms of given population N of insurers taking part in the assessment, indicator scores would need to be re-scaled by the factor 1-(N-n)/N.

Examples of NTNI activities include speculative derivatives trading, guarantees for financial transactions, leveraging assets through securities lending and minimum guarantees on variable insurance products.

This version succeeded “Proposed G-SII Assessment Methodology”, which the (IAIS, 2012c) issued for public consultation on 31 May 2012 in the effort to develop and test possible methodologies for identifying G-SIIs (and any coordination that may be required among insurance supervisors). IAIS had previously completed an initial data call of 48 insurance forms in August 2011. The group of G-SIIs will be updated annually and published by the FSB each November based on new data, starting in 2014.

See Annex I; IAIS (2013a).

The current list of G-SIIs will be updated annually by the IAIS based on a new data call from candidate firms that meet the minimum criteria of total insurance assets of no less than US$60 (200) billion and gross written premiums (GWP) of at least (less than) 5 per cent of the group’s total GWP are generated outside the home market (or are nominated by their respective supervisory authority). Since the SIFI approaches for G-SIBs and G-SIIs are conditional on a pre-selection of candidate institutions based on a minimum size criterion, they imply different economic significance of a SIFI designation given that G-SIIs are much smaller and less interconnected to other financial services providers than G-SIBs (The Geneva Association, 2012b).

The FSB deferred its decision on the G-SII status of, and appropriate risk mitigating measures for, major reinsurers to July 2014.

After preparing the position paper on the role of insurance companies in financial stability analysis (IAIS, 2011a), the IAIS also examined more closely financial stability implications of the reinsurance sector in collaboration with the FSB (IAIS, 2012b).

HLA helps reduce the probability of distress or failure of G-SIIs and, thus, mitigates the expected impact their distress or failure by internalising some of the associated cost to the financial system and overall economy (which are otherwise externalities to the insurance group).

FSB (2011c, 2013b).

HLA will apply starting from January 2019 to those G-SIIs identified in November 2017, using the IAIS methodology.

Note that the IAIS has also established a work plan for the development of comprehensive, group-wide supervisory and regulatory framework for IAIGs, including an international capital standard (ICS), which may include all (or some) of the features of the BCR.

Such determination would be made based on whether material financial distress at the nonbank financial company, or the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or the mix of activities of such company, could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States (United States of America, 2010).

The Geneva Association (2011c) also claims that having separate efforts could duplicate supervisory data requests, result in inconsistent analysis of the risks posed by individual nonbank financial companies, and distort markets’ perception of these risks.

References

Acharya, V.V., Pedersen, L.H., Philippon, T. and Richardson, M.P. (2009) Measuring systemic risk, Working Paper presented at Research Conference on Quantifying Systemic Risk, 6 November, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, from www.clevelandfed.org/research/conferences/2009/11-6-2009/index.cfm, accessed 23 February 2014.

Acharya, V.V., Pedersen, L.H., Philippon, T. and Richardson, M.P. (2010) Measuring systemic risk, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper 10-02, from www.clevelandfed.org/research/workpaper/2010/wp1002.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Acharya, V.V., Pedersen, L.H., Philippon, T. and Richardson, M.P. (2012) Measuring systemic risk, CEPR Discussion Paper 8824, February, from www.cepr.org/pubs/new-dps/dplist.asp?dpno=8824&action.x=0&action.y=0, accessed 23 February 2014.

Adrian, T. and Brunnermeier, M.K. (2008) CoVaR, Staff Reports 348, New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2011) “Macroprudential regulation and policy”, Proceedings of a joint conference organized by the BIS and the Bank of Korea in Seoul on 17–18 January 2011, Monetary and Economic Department, BIS Papers No. 60, December, Basel: Bank for International Settlements, from www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap60.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2013) Global systemically important banks: updated assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement, July, Basel: Bank for International Settlements, from www.bis.org/publ/bcbs255.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2012) Models and tools for macroprudential analysis, Basel Committee Working Paper no. 21, April, Basel: Bank for International Settlements, from www.bis.org/publ/bcbs_wp21.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2011) Global systemically important banks: Assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement, July, Basel: Bank for International Settlements, from www.bis.org/publ/bcbs201.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2009) Revisions to the Basel II market risk framework, July, Basel: Bank for International Settlements, from www.bis.org/publ/bcbs148.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) (2008) Insurance (Prudential Standards) (Class 4 and Class 3B Solvency Requirement) Rules 2008 (Consolidated, excluding Schedules VII, VIII, IX and X), BR 83/2008, Bermuda Monetary Authority, Hamilton.

Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) (2011) Commercial Insurer’s Solvency Self-Assessment (CISSA)—Instruction Handbook, 21 January, Bermuda Monetary Authority, Hamilton.

Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) (2012a) Enhancements to the Regulatory and Supervisory Regime for Commercial Insurers, Consultation Paper, 13 January, Bermuda Monetary Authority, Hamilton.

Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA) (2012b) Insurance (Prudential Standards) (Class 4 and Class 3B Solvency Requirement) Amendment Rules 2012, BR 91/2012, 13 December, Bermuda Monetary Authority, Hamilton.

Billio, M., Getmansky, M., Lo, A.W. and Pelizzon, L. (2010) Econometric measures of systemic risk in the finance and insurance sectors, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper no. 16223, from www.nber.org/papers/w16223, accessed 23 February 2014.

Brownlees, C.T. and Engle, R.F. (2011) Volatility, correlation and tails for systemic risk measurement, Working Paper, 24 May, NYU Stern School of Business, from www.vleda.stern.nyu.edu/scrc/?p=2241, accessed 23 February 2014.

Brown, D.M. and Warren-Boulton, F.R. (1988) Testing the structure-competition relationship on cross-sectional firm data, Discussion Paper 88-6 (11 May), Economic Analysis Group, U.S. Department of Justice.

Chan-Lau, J. (2010) Regulatory capital charges for too-connected-to-fail institutions: A practical proposal, IMF Working Paper 10/98, Washington, DC, International Monetary Fund, from www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp1098.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Drehmann, M. and Tarashev, N. (2011) ‘Systemic importance: Some simple indicators,’ BIS Quarterly Review, pp. 25–37, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1103e.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2010) “Reducing the moral hazard posed by systemically important financial institutions”, Interim Report to the G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 18 June, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_100627b.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2011a) Understanding financial linkages: A common data template for global systemically important banks, Consultation Paper, 6 October, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111006.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2011b) Global adherence to regulatory and supervisory standards on international cooperation and information exchange, Public Statement, 2 November, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111102.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2011c) The key attributes of effective resolution regimes for financial institutions, 4 November, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_111104cc.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2012) Increasing the intensity and effectiveness of SIFI supervision, Progress Report to the G20 Ministers and Governors, 1 November, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_121031ab.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2013a) Global Systemically Important Insurers (G-SIIs) and the Policy Measures That Will Apply to Them, Press Release, 18 July, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130718.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB) (2013b) Assessment Methodology for the Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions, Consultative Document, 23 August, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_130828.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB)/International Monetary Fund (IMF)/Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2009) Guidance to Assess the Systemic Importance of Financial Institutions, Markets and Instruments: Initial Considerations, Report to the G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 28 October, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_091107c.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB)/International Monetary Fund (IMF)/Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2011a) Macroprudential Policy Tools and Frameworks, Progress Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 26 October, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.bis.org/publ/othp17.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB)/International Monetary Fund (IMF)/Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2011b) Macroprudential Policy Tools and Frameworks, Update to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, March, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.bis.org/publ/othp13.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Board (FSB)/International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) (2014) Assessment Methodologies for Identifying Non-Bank Non-Insurer Global Systemically Important Financial Institutions—Proposed High-Level Framework and Specific Methodologies, Consultative Document, 8 January, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.financialstabilityboard.org/publications/r_140108.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) (2011) Authority to Require Supervision and Regulation of Certain Nonbank Financial Companies, Second Notice of Proposed Rulemaking and Proposed Interpretive Guidance, Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 201 (18 October), pp. 64264-64283, from www.federalregister.gov/articles/2011/10/18/2011-26783/authority-to-require-supervision-and-regulation-of-certain-nonbank-financial-companies#p-265, accessed 23 February 2014.

Gray, D.F. and Jobst, A.A. (2010) ‘New directions in financial sector and sovereign risk management’, Journal of Investment Management 8 (1): 23–38.

Gray, D.F. and Jobst, A.A. (2011a) ‘Systemic contingent claims analysis—A model approach to systemic risk’, in J.R. LaBrosse, R. Olivares-Caminal and D. Singh (eds.) Managing Risk in the Financial System, London: Edward Elgar, pp. 93–110.

Gray, D.F. and Jobst, A.A. (2011b) “Modelling systemic financial sector and sovereign risk”, Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review, No. 2, pp. 68–106, from www.riksbank.se/upload/Rapporter/2011/POV_2/er_2011_2.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Hirschman, A.O. (1964) ‘The paternity of an index’, American Economic Review 54 (5): 761.

Houben, A. and Teunissen, M. (2011) ‘The systemicness of insurance companies: Cross-border aspects and policy implications’, in P.M. Liedtke and J. Monkiewicz (eds.) The Future of Insurance Regulation and Supervision—A Global Perspective, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 246–69.

Huang, X., Zhou, H. and Zhu, H. (2009) ‘A framework for assessing the systemic risk of major financial institutions’, Journal of Banking and Finance 33 (11): 2036–49.

Huang, X., Zhou, H. and Zhu, H. (2010) Assessing the systemic risk of a heterogeneous portfolio of banks during the recent financial crisis, Working Paper no. 296, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.bis.org/publ/work296.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2009) Systemic risk and the insurance sector, 25 October, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/__temp/Note_on_systemic_risk_and_the_insurance_sector.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2010a) Macroprudential Surveillance and (Re)Insurance, Global Reinsurance Market Report, Mid-year Edition, 26 August, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/9926.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2010b) Position Statement on Key Financial Stability Issues, 4 June, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/__temp/IAIS_Position_Statement_on_Key_Financial_Stability_Issues.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2011a) Insurance and Financial Stability, November, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/13348.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2011b) Insurance Core Principles, Standards, Guidance and Assessment Methodology, 1 October, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, pp. 357–360, from www.iaisweb.org/__temp/Insurance_Core_Principles__Standards__Guidance_and_Assessment_Methodology__October_2011.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2011c) Global Reinsurance Market Report, 23 December, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/Global-Reinsurance-Market-Report-GRMR-538, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2012a) Global Systematically Important Insurers: Proposed Policy Measures, Public Consultation Document, 17 October, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/16023.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2012b) Reinsurance and Financial Stability, 19 July, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/16023.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2012c) Global Systemically Important Insurers: Proposed Assessment Methodology, Public Consultation Document, 31 May, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/15384.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2013a) IAIS Releases Global Systemically Important Insurers Assessment Methodology and Policy Measures, Macroprudential Policy and Surveillance Framework, Press Release, 18 July, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/db/content/1/19152.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2013b) Global Systemically Important Insurers: Final Initial Assessment Methodology, 18 July, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/19151.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2013c) Global Systemically Important Insurers: Final Policy Measures, Press Release, 18 July, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/19150.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2013d) Macroprudential Policy and Surveillance in Insurance, Macroprudential Surveillance and Policy Subcommittee (MPSSC), 18 July, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/view/element_href.cfm?src=1/19149.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) (2013e) Basic Capital Requirements: Proposal for Basic Capital Requirements (BCR) for Global Systemically Important Insurers (G-SIIs), Public Consultation, 20 December, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, from www.iaisweb.org/News/Consultations/Basic-Capital-Requirement-1141, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2010) Integrating Stability Assessments Under the Financial Sector Assessment Program into Article IV Surveillance: Background Material, Monetary and Capital Markets Department, 27 August, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, pp. 3–15, from www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2010/082710a.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2011a) Toward Operationalizing Macroprudential Policies: When to Act? Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 3, September, World Economic and Financial Surveys, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, from www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/2011/02/pdf/ch3.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2011b) ‘Macroprudential policy: An organizing framework’, Monetary and Capital Markets, 14 March, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, from www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2011/031411.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2013) Key Aspects of Macroprudential Policy, Board Paper, 10 June, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, from www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/061013b.pdf.

Jobst, A.A. (2013) ‘Multivariate dependence of implied volatilities from equity options as measure of systemic risk’, International Review of Financial Analysis 28 (June): 112–29.

Jobst, A.A. and Gray, D.F. (2013) Systemic contingent claims analysis—Estimating market-implied systemic risk, IMF Working Paper No. 13/54, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, from www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1354.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Jones, R.C., Griffith, J.E., Iten, J. and Vine, M.J. (2013) “Global insurance key risks and credit trends dominated by low interest rates and regulation issues,” Ratings Direct, Standard and Poor’s Rating Services, RatingsDirect on the Global Credit Portal, 21 January, from www.standardandpoors.com/spf/upload/Ratings_EMEA/2013-01-21_GlobalInsuranceKeyRisksAndCreditTrends.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Lehmann, R.J. and Lehrer, E. (2011) Comments on Report to Congress on How to Modernize and Improve the System of Insurance Regulation in the United States, Center on Finance, Insurance and Real Estate, 29 November, The Heartland Institute, Washington, DC, from www.heartland.org/sites/default/files/Heartland_Comments_to_Federal_Insurance_Office.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

Liedtke, P.M. (2011) Assessment of systemic risk indicators in the insurance sector, Working Paper series of The Geneva Association, Etudes et Dossiers, No. 377 (presented at the 13th Meeting of The Geneva Association’s Amsterdam Circle of Chief Economists (17–18 February) and the 7.5th International Liability Regimes Conference of The Geneva Association, 17 June, August, from www.genevaassociation.org/PDF/Working_paper_series/1_GA_E&D_377_05_LIEDTKE_Finance,Systemic_risk,SIFIs.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

The Geneva Association (2010a) Systemic Risk in Insurance—An Analysis of Insurance and Financial Stability, Special Report of the Geneva Association Systemic Risk Working Group, March, Geneva: The International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, from www.genevaassociation.org/portals/0/Geneva_Association_Systemic _risk_in_Insurance_Report_March2010.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.

The Geneva Association (2010b) Key Financial Stability Issues in Insurance—An Account of the Geneva Association Ongoing Dialogue on Systemic Risk with Regulators and Policy-Makers, July, The International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, Geneva, from www.genevaassociation.org/pdf/BookandMonographs/Geneva_ Association_Key_Financial_Stability_Issues_in_ Insurance_July2010.pdf, accessed 23 February 2014.