Abstract

This paper uses the tools of welfare economics to analyse the appropriate mix of private sector and government responses to catastrophic events. In particular, we examine the appropriate roles of post-disaster government aid, private insurance and mitigation activities. The analysis focuses on the distinction between the ex ante and ex post welfare criteria, as well as incentive issues such as may arise from the Samaritan's dilemma. A key factor is that individuals maintain differing subjective beliefs concerning the probability or magnitude of the catastrophic event. The analysis applies to insurance markets certain concepts that are now also being developed in the finance literature to examine the efficiency of naked credit default swaps and other instruments that are in essence side bets among agents with heterogeneous beliefs. We conclude that ex post welfare economics provides fundamental insights that have not been previously integrated into the discussions concerning the losses created by catastrophic events, including a potential role for mandatory insurance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

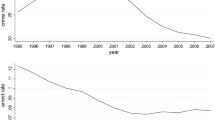

The dollar magnitude of government aid provided in the aftermath of natural disasters and terrorist attacks in the United States (U.S.) shows a sharply rising trend and is now high enough to become a major budgetary issue. This outcome is the result of secular trends in the loss severity and frequency of catastrophes (see Figure 1) as well as the high proportion of the catastrophic losses that now receive U.S. government aid (see Figure 2). Similar trends are evident in other countries (see Swiss Re,Footnote 1 European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Directorate-General,Footnote 2 and Brattberg and RhinardFootnote 3).

Recognising these trends, recent papers by Cummins et al.Footnote 4 and Michel-Kerjan and Volkman WiseFootnote 5 have raised the question of how to constrain the rapidly expanding government largesse in providing post-disaster relief. The presumption that government disaster aid should be constrained arises in part from the U.S. political process, whereby disaster aid creates a chain of political benefits, starting with the U.S. President who designates a federal disaster, through the sequence of state governors and local mayors who help distribute the aid, and finally, to the business and individual beneficiaries. Similar mechanisms appear to operate in other developed countries (see European Commission GeorgievaFootnote 6).

There is, however, a more primary question, namely, what are the welfare benefits of post-disaster government aid. Unfortunately, the existing literature provides little systematic analysis of the fundamental principles of welfare economics that underlie the public provision of post-disaster aid. The purpose of this paper is to attempt to fill this gap by applying key ideas from the welfare economics of uncertainty to the design of public catastrophe loss programmes. One major conclusion of our analysis is that post-disaster government aid may well be welfare enhancing, even in the presence of ex ante insurance markets. However, as the paper develops, this conclusion must be tempered in view of several factors, including the frictional costs of lump sum government transfers, specific mechanisms that may operate in insurance markets, and the possible role for ex ante mitigation activities.

We begin the next section with a brief review of the trends and severity of catastrophic events and the amount of post-event government aid.

The subsequent section then takes up the fundamental question whether a government's welfare decisions should focus on providing citizens with ex ante opportunities to insure against the evident risks, or whether there is also a fundamental role from welfare economics for ex post disaster relief. We propose that welfare economics provides a fundamental role for ex post disaster relief that has not been previously integrated into the discussions involving disaster aid, insurance and mitigation.

In the following section, we turn to the policy implications that arise from combining the fundamental welfare role for governmental ex post disaster aid with the incentive conflicts it creates for individuals to purchase insurance and/or mitigate the underlying risks. The issue is complex. A major complication is that interactions exist among four factors discussed in the next section: the increasing severity of the catastrophes, the rising trend of government aid, the substitution of government insurance for private insurance and the incentive of homeowners and even the government itself not to mitigate the underlying risks. For example, while the increasing number and size of the catastrophes no doubt was a major factor leading to the substitution of government insurance and post-disaster aid for private insurance, it is also clear that subsidised government insurance and free post-disaster aid has encouraged greater development in risky areas, thereby expanding the dollar magnitude of the resulting losses.

The last section provides concluding comments.

In the Appendix, we discuss additional issues raised by the Samaritan's dilemma that may interfere with the ex ante incentives of the victims to help themselves by mitigating the risks or purchasing insurance (see BuchananFootnote 7). This gives rise to a problem of time inconsistency. As Kunreuther and PaulyFootnote 8 note, time inconsistency arises in a number of economic areas, and indeed was originally illustrated by Kydland and PrescottFootnote 9 as a problem in the design of a programme of flood relief, although their focus was the design of macroeconomic policy. While the Samaritan's dilemma may affect the design details of government disaster-aid programmes, the broad welfare implications of government interventions discussed in the following text stand on their own.

Trends in catastrophic events and government disaster aid

There have been four major trends in catastrophic events and government responses:

-

1)

The severity and number of catastrophic events appear to be steadily rising, (see Figure 1). Kunreuther and Michel-KerjanFootnote 10 note that properties are built in risky locations due to subsidised government insurance and behavioural misperceptions of the risk. Major events are occurring around the world, with recent examples including the Japan and New Zealand earthquakes and Thailand floods (all in 2011), and the U.S. storm Sandy (2012).

-

2)

Government disaster relief has grown significantly, as illustrated by the expanding activities carried out by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other U.S. agencies (see Figure 2 and Michel-Kerjan and Volkman Wise5). Table 1 provides a unique tabulation of the wide range of U.S. government agencies that provide various forms of post-disaster aid. The table also shows that the aid is directed to three primary areas: housing, emergency response and rebuilding of public infrastructure. Dixon and SternFootnote 11 show that, of the total payments in response to the 9/11 terrorist attack, 42 per cent of the payments came from government, 51 per cent from insurance and 7 per cent from charities.

Table 1 United States allocations in response to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma as of 21 August 2006 -

3)

Private catastrophe insurance markets for U.S. floods and earthquakes have steadily disappeared, spawning government insurance programmes as replacements.Footnote 12 The government programmes have serious drawbacks including subsidies, lack of risk-based premiums and low take-up rates (see PriestFootnote 13). Figure 1 shows that the total losses significantly exceed the insured losses. Markets for catastrophe bonds hold promise to allow the private insurance markets to function based on capital market funding, but their success to date has been limited (see Bantwal and KunreutherFootnote 14 and FrootFootnote 15).

-

4)

Both public and private sector actions to mitigate the underlying risks, including avoiding development in risky areas and physically reinforcing structures, have been limited (see for example KunreutherFootnote 16 and ComerioFootnote 17).

Going forward, future mega catastrophes cannot be ruled out. Figure 3, for example, shows estimates of “reference losses” projected by Swiss Re in 2007. Reference losses are Swiss Re's estimates of catastrophes with return periods of between 200 and 1,000 years. They projected a Japanese earthquake could create US$500 bn in total losses, a value that, interestingly, equals some current estimates of the total from the 2011 Japanese earthquake. They also total project losses in the range of US$300 bn for both future U.S. earthquakes and hurricanes.

A major earthquake centred on the San Francisco Bay Area Hayward Fault presents an interesting case study (and one close to home for the authors). Consistent with the Swiss Re projection, Holden et al.Footnote 18 state, “an earthquake of this magnitude in the San Francisco Bay Area could have an even greater impact on businesses, employees, and payrolls in the area than Hurricane Katrina had in Louisiana and Mississippi”.

The 1994 California Northridge earthquake provides an excellent case study of how government insurance may replace private insurance following a major event. Prior to the Northridge earthquake, earthquake coverage was available as a rider to all California homeowner policies. However, insurance payments on Northridge claims far exceeded the insurers’ loss estimates for such an event (see Risk Management SystemsFootnote 19). As a result, soon after Northridge, most insurers stopped offering earthquake coverage. The replacement is a public/private earthquake insurance plan (the California Earthquake Authority). The insurance premiums reflect the high cost of reinsurance and catastrophe bonds, with the result that only about 12 per cent of California homeowners purchase coverage (relative to 30 per cent in the early 1990s) (see PomeroyFootnote 20).

It is an open question to what degree the uninsured California homeowners anticipate state and federal governments will help fund the reconstruction of their homes after a major earthquake. There was a time in which such government aid would surely not have been anticipated. MossFootnote 21 provides the example of U.S. President Grover Cleveland who in 1887 vetoed a bill to assist the victims of a severe drought in Texas, declaring, “I do not believe that the power and duty of the General Government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering. … Though the people support the Government, the Government should not support the people”. More recently, both KunreutherFootnote 22 and Comerio17 cite evidence that many homeowners do not anticipate government aid to rebuild their homes.

Self-insurance may also be a sensible economic decision for California homeowners to the extent that wood-frame single-family homes can be protected against most earthquake damage at a cost that may well be less than the present value of future insurance premiums.Footnote 23 On the other hand, these homeowners are surely aware of the rising trend in government post-disaster aid that has been documented in this section, and it would be reasonable for them to expect government generosity in response to a large earthquake.

Welfare economics of catastrophes: ex post vs ex ante criteria

The following theorem is well known.

Theorem 1:

-

When a population of n identical risk-averse individuals face a common risk of fixed size, each individual's expected utility is maximised by having each of them bear 1/nth of the risk.

This theorem is just an application of Samuelson's well-known theorem that it pays to diversify (SamuelsonFootnote 24). It can also be viewed as an application of the earlier fundamental risk sharing theorem of Borch.Footnote 25

To first order, this theorem is neutral with regard to the question of how this risk sharing is to be financed. It can be financed ex ante through an insurance market in which premiums are paid into a common pool. But it can also be financed by ex post relief paid for by a poll tax levied on each citizen. At this level, the theorem is neutral between ex post relief vs ex ante insurance.

Of course, second-order effects may be important. Competitive insurance markets may have lower administrative costs of claims settlement and may be better at targeting loss compensation, and a poll tax may not be politically feasible, but under the assumptions of the theorem, there is no reason not to provide ex post relief.

Systemic differences appear, however, when we relax the theorem's assumptions. If individuals differ in their beliefs, the Pareto criterion based on expected utility loses its consensus welfare appeal. For broader measures of welfare, even when they are based solely on individual well-being, there can be tension between the evaluation of welfare before an event occurs (ex ante optimality) and the evaluation once the outcome is revealed (ex post optimality). In choosing among policies to deal with catastrophe loss, we would like to use the framework of established welfare economics. Unfortunately under the conditions of uncertainty inherent to catastrophic events, there is as yet no consensus on how to do this.

A related issue is that that some individuals may apply particularly low estimates for the probabilities of catastrophic events (see Kunreuther and Pauly8). To the extent that these estimates are accepted as the subjective probabilities of these individuals, this case fits fully within our analysis. However, if it is assumed that these cases reflect systematic errors in judgement, the usual principle of consumer sovereignty will clash with the desire to protect individuals from themselves. For example, this behavioural concern is the basis of the desire to “nudge” (Thaler and SunsteinFootnote 26). While we recognise the importance of such behavioural issues, they are separable from the focus in this paper on the problems of welfare measurement that arise under uncertainty when individuals maintain differing subjective beliefs. We do, however, comment further on this issue in the conclusions.

The particular focus in this paper is on the dilemma generally described as ex ante vs ex post optimality.Footnote 27 This dilemma arises even when individual behaviour is assumed to satisfy the traditional von Neumann and Savage axioms. The fundamental problem is that under these axioms subjective probabilities can differ across individuals in the same way that preferences may differ, and when this is true, some insurance contracts may be written that serve only to exploit the difference in opinion. Once it is known which state has occurred, however, differences of opinion disappear, and payments under these insurance contracts may no longer be welfare enhancing if the contract simply represents a bet between optimists and pessimists regarding the likelihood of the event.Footnote 28 On the other hand, insurance contracts may remain welfare enhancing if they are used only to hedge against the physical losses individuals face if a particular event occurs, a case of what is termed an insurable interest. We return to this question below.

The question of which measure of individual welfare to respect immediately arises from the ex ante vs ex post issue. Should it be individual well-being, as measured by expected utility (subjective probabilities being taken at face value), that is, individual ex ante welfare before it is revealed whether or not a catastrophe has occurred? Or should it be ex post individual welfare as measured by the (probability-free) utility after it is known whether or not a catastrophe took place?Footnote 29 Until this question is settled, the definition of social well-being as determined by a (Bergson) social welfare function will also be open to debate.

This dilemma makes for difficulties in interpreting the standard Arrow-Debreu formulation of welfare under uncertainty (Arrow,Footnote 30 DebreuFootnote 31). Recall that in the case in which individuals satisfy the von Neumann and Savage axioms, the preferences of individual i over state-contingent consumption bundles x j can be represented by a function of the form

where j is the index of the state, p j is the probability of state j, and u is a cardinal utility function assumed to be state independent.

A feasible allocation is Arrow-Debreu efficient if there is no alternative feasible allocation which is Pareto superior in terms of the Vi. But, as MirrleesFootnote 32 notes: “The Arrow-Debreu formulation of welfare accepts each household's beliefs—possibly expressible by means of subjective utilities—in the same way that it accepts the household's tastes. If a man strongly but wrongly believes that the end of the world is at hand, he will be given his wealth and allowed to spend it all at once. He will then starve in circumstances he believed would not occur, but an Arrow-Debreu welfare function does not care”.

The concept of efficiency implied by applying the Pareto criterion to the functions Vi is known as “ex ante” efficiency. An allocation of resources is said to be ex ante efficient if it provides an “optimal allocation of risk bearing” (ArrowFootnote 33). Under general conditions, insurance markets can be expected to guarantee this. But, as StarrFootnote 34 points out, if we consider the allocation of resources that results from the trading of insurance contracts not before but after the outcome of the insured event is known (i.e. ex post), there may be for each realised state a feasible redistribution of resources within that state which increases some agent's (actual) utility without lowering the realised utility of anyone else. As Starr states, “ If we are interested in satisfactions actually realized rather than those which are merely anticipated, the appropriate quality to seek is that there be no redistribution that will increase some trader's realized utility while decreasing no trader's realized utility. Such a situation will be termed an ex-post Pareto optimum”.

In this paper we do not add to the continuing debate on the relative normative merits of the ex ante vs (several) ex post viewpoints. A clear statement of the deep issues involved may be found in Kolm.Footnote 35 For recent contributions supporting the ex post viewpoint, see Adler and SanchiricoFootnote 36 and Fleurbaey.Footnote 37 Our goal, instead, is to explore the implications of the ex ante vs ex post debate for the design of programmes to deal with the risk of catastrophe loss. We would note, however, that to the extent that welfare economics exists to guide government policy, government policy based on the “ex ante optimality” slogan, “you could have purchased the optimal amount of insurance, why are you complaining?” will not gain much traction, as has been vividly demonstrated again in the U.S. following the 2012 Sandy storm.

Insurance and ex post Pareto efficiency: The Starr case

We now assume that policymakers have adopted the ex post Pareto efficiency criterion. Then the question arises of how best to deal with the risk of catastrophic loss, particularly as compared with policies that adopt the ex ante criterion. We begin by examining the insurance/relief implications of an ex post efficiency criterion due to Starr.34

We use the following simple example from Harris and Olewiler.Footnote 38 An economy lasts for two periods. In period 0, there is no uncertainty. In period 1, there are two possible states of nature. In state C, a catastrophic loss occurs, and in state N, there is no loss. The economy is endowed with a single commodity, X. In period 0, the endowment is X̄0. If a catastrophic event occurs (in period 1), the endowment is X̄C and if not, the endowment is X̄ N , with X̄ C < X̄ N

The economy has two citizens, A and B. They have the same endowment, X̄ j /2 j=0, C, N. At time 0, the preferences of both citizens can be represented by a time-separable state independent expected utility function, identical in all respects except one. Individual A believes that the probability of a catastrophic event is low, p L , whereas individual B thinks it is high, p H .

The expected utility of each citizen is thus given by

where X j i is the consumption of X by individual i, i=A, B in time/state j, j=0, C, N.

Assuming differentiability, the consumption bundle X̂ j i, i=A, B, j=0, C, N is ex ante Pareto efficient if it is feasible, ∑ i X̂ j i=X̄ j i=A, B, j=0, C, N, and if the marginal rate of substitution of period 0 consumption for contingent state j consumption, j=C, N, is the same for each individual. That is, we must have

for the catastrophe state C, and the equivalent equation for the non-catastrophe state N.

The equality in Eq. (1) can be achieved by competitive trading. Since there are three goods in this model (i.e. one good indexed by three indices (time 0, state C and state N), we will need three prices. Normalising by setting the price of X at time 0 to equal 1, we may interpret the two other prices as insurance premiums paid for the delivery of 1 unit of the good if there is a catastrophe (i.e. state C) or not (i.e. state N). Individual A (the optimist) will write an insurance policy for the benefit of individual B (the pessimist) for a premium to be paid in period 0, such that A will increase the endowment of B in the state in which the catastrophe occurs.

More generally, for m periods, n states, k consumers and l commodities, under standard assumptions, any allocation which is competitive in spot markets and contingent claims (insurance) markets is ex ante efficient. Conversely, any allocation that is ex ante efficient will be a competitive outcome for spot markets and insurance arrangements, given suitable lump sum transfers.

This is the basis of the standard welfare argument in favour of insurance markets. Suppose, however, that in defining Pareto efficiency we use ex post preferences, that is, efficiency once the outcome is known. This can be done in more than one way. Here we use the approach of Starr34.

Definition:

-

Starr ex post efficiency.An allocation X̂ j i, i=A, B, is ex post Pareto efficient in state j if it is feasible, ∑ i X̂ j i=X̄ j i=A, B, and there is no other feasible allocation X j i for which U(X j i)⩾U(X̂ j i)i=A,B with strict inequality for at least one i.

An allocation is (universally) ex post Starr efficient if it is ex post Starr efficient for each state j=C, N.

By Starr's criterion, for each state j=C, N, ex post Pareto efficiency requires that the marginal rate of substitution of period 0 consumption for actual (not contingent) state j consumption in that state be equal for each individual. That is, we must have

Now looking at (1) and (2) it is clear, as DrezeFootnote 39 and Starr34 noted, that unless the subjective probabilities p L , p H are equal for each citizen, the ex ante and (Starr) ex post Pareto efficient allocations will not coincide.

How likely is it that subjective probabilities of catastrophic loss will vary across individuals? In Kunreuther and Pauly,8 a theoretical explanation is given for why individuals may not seek information on the probabilities of low-frequency events. In this case subjective probabilities are likely to differ, including the behavioural case in which some individuals systematically underestimate the true probability of a catastrophic event (see Kunreuther et alFootnote 40). The role of heterogeneous beliefs in financial markets, such as equity markets, is also receiving more attention, in part due to the evident differences in beliefs that were revealed during the subprime crisis.Footnote 41

But, even when individuals seek information, say, by trying to infer probabilities from market prices, difficulties will arise.Footnote 42 Catastrophe bonds, for example, offer interest rate spreads that are far higher than the expected losses, in some cases, an “excess spread” of 5 per cent or more. Bantwal and Kunreuther14 and Froot15 have offered several explanations for this risk premium, ranging from non-standard preferences to capital market imperfections. Since it is difficult to know what is causing the premium to far exceed the expected loss, it is clearly not possible for agents to infer the underlying probabilities just from the catastrophe bond's price. Moreover, although there is not a large amount of empirical literature on this question, Botzen et al.Footnote 43 show that in Holland, risk perceptions for the probability of floods do differ, and they provide empirical correlates for the differing subjective utilities. It seems reasonable therefore to suppose that the preconditions for equality between ex ante and ex post optimality will not be met.

What does this imply for the choice between insurance and ex post (state-dependent) transfers? Since individuals are identical except for their subjective probabilities, ex post Starr; efficiency requires that each individual simply consume his or her endowment in each state that is, no trade takes place. Each agent thus attains the same level of utility. But, given that individuals differ in their subjective probabilities, they will write ex ante insurance contracts based on their differing views of the likelihood of loss. Then, in the event of a catastrophe, settlements will take place. The optimist suffers a loss of endowment, (offset by her gain in period 0), the pessimist experiencing the reverse. This is ex post Pareto inefficient in the catastrophe state. By adapting the same argument, it is also ex post inefficient in the state in which a catastrophe does not occur. Thus it is ex post inefficient in the Starr sense.

How could a government achieve ex post efficiency? Suppose a catastrophe occurs. Then since p H >p L , ex ante trading in insurance markets to satisfy Eq. (1) will force

Thus ex post relief in which the government redistributes resources from B to A will lead to an ex post Pareto improvement. Here then is an example in which, by one welfare measure (Starr ex post Pareto efficiency), government relief is efficient, but insurance is not. Indeed the government relief is simply undoing the misallocation caused by the insurance, so a policy which banned insurance would work as well. To be clear, there may exist a separate and very important role for insurance if, for example, individual agents differed in their initial endowments across the states of nature.

Insurance and ex post Pareto optimality: The general case

Because the Starr test of efficiency is defined from within a given state and ignores effects across states, it has been argued (see HammondFootnote 44) that the Starr definition makes the set of ex post inefficient allocations too large. Hammond analyses the implications of a definition of ex post efficiency that widens the set of efficient states. In his sense a feasible allocation X̂ j i, i=A,B, j=0, C, N is ex post efficient if there is no alternative feasible allocation X j i, i=A,B, j=0, C, N which is Pareto superior for all ex post utility functions U() in different states of the world. That is, for which {U(X0i), U(X j i)}⩾{U(X̂0i),U(X̂ j i) i=A,B, j=C, N.Footnote 45

With this definition, Hammond proves the following result. If an allocation is efficient ex ante, it must be efficient ex post, except possibly for states of the world j and consumers i for whom P j i=0. Since we know that spot markets with contingent insurance markets are in general ex ante efficient, this definition of welfare reinstates the argument for insurance even when the ex post criterion is used.

The concept of Pareto efficiency, however, provides only rather weak welfare comparisons. If we are prepared to measure welfare outcomes by a (Bergson) social welfare function, the distinction between ex ante and ex post again becomes important. An ex ante Bergson social welfare function is a function W a of consumers’ ex ante expected utility Vi which is increasing in each Vi; W a =W a (Vi) for all i.

An ex post social welfare function, on the other hand, is a function which is increasing in each consumer's ex post utility in state j, Yi=U(X0i)+U(X j i)

Here π j is the social probability of state j, and may differ from the subjective probability P j i. An ex post welfare optimum is a maximum of W p .

Hammond proves the following theorem:

Theorem 2:

-

Every ex post welfare optimum will be ex ante efficient if and only if(a) for all i=A, B and j=C,N, P j i=π j (b) for all j=C, N, W=∑ i μiYi, i=A,B.Footnote 46

We have already discussed the likelihood that individuals will differ in their subjective probabilities. The second requirement forces each consumer to display the same individual attitude to risk as the social attitude to risk (see Hammond, p. 24144).

Both requirements are needed to prevent individuals who disagree ex ante (whether in their beliefs or in their attitude to risk) from writing insurance contracts that will move the allocation away from the ex post social optimum.

Suppose that the conditions of Theorem 2 are not satisfied. How can an ex post allocation be decentralised? As Hammond shows, one way to do this is with spot markets and state-contingent lump sum transfers. That is to say, if the welfare goal is the maximisation of ex post welfare and if individuals differ either in their beliefs or in their attitudes to risk, a system of ex post lump sum relief is the appropriate way to deal with catastrophic loss. Moreover, there is incentive to close the insurance markets lest they interfere with the optimal allocation, although, again, with the caveat that the insurance markets may provide other benefits. If the insurance markets do remain open, ex post relief will need to be changed to undo some of the risk transfers that occur in these markets.

These conclusions of welfare economics are starkly at variance with the standard arguments for using insurance markets to handle catastrophic risk. In the concluding section, we will discuss their practical implications for catastrophe loss policy design.

Policy responses

If we take the implications of ex post welfare economics literally, the following conclusions would emerge:

-

i)

continue and even expand as necessary the government's post-disaster aid programmes;

-

ii)

prohibit the relevant insurance markets, or at least maintain the catastrophe insurance programmes at their currently low levels.

Overall, this is an endorsement of government aid and catastrophe insurance markets as they now operate. The ex post view is, however, based on important assumptions and, if these assumptions do not hold, then a range of second-best policies should be considered. We focus on two issues:

-

1)

The ex post view is based on an exchange economy that takes as given the initial endowments. In reality, a relatively wide range of ex ante mitigation actions are available, and it seems relevant to evaluate them either as additions to or as substitutes for government transfers.

-

2)

The ex post view assumes that lump sum transfers can be made without cost. The reality, of course, is that lump sum transfers create dead weight costs since they must be funded with taxes. Given the fiscal crisis currently facing many governments, it seems relevant to evaluate second-best policies that might encourage ex ante insurance as a substitute for government transfers.

We begin by discussing the issue of mitigation.

Expanding incentives for ex ante mitigation

The introduction of production into the ex post welfare model is widely understood to create complexities (see Starr,34 Harris,Footnote 47 Hammond44). This literature, moreover, is silent on one of the major problems of ex post government aid, namely, the possibility that government disaster assistance may reduce the incentives of individuals to limit their potential loss through mitigation activities. In the Appendix, we provide a discussion of the Samaritan's dilemma as a problem of time inconsistency. Here we simply note that to the extent that positive net present value (NPV) mitigation investment opportunities exist, they would appear to be ex post welfare enhancing even in the presence of lump sum transfers, and all the more so if the transfers are limited.

The main issue for mitigation actions is that many households appear unwilling to carry out the necessary investments, even when they are NPV positive. The basis of the limited mitigation actions is not well understood, and it is quite possible that there are multiple factors, each having its own resolution (see Kunreuther16). One factor, within the scope of this paper, is that individuals may anticipate negative NPV outcomes because they are applying low subjective probabilities for the underlying event. In line with the discussion of the previous section, an ex post welfare criterion would take this as given, and would therefore recommend lump sum transfers for the losses that result from the failure to mitigate. But, if the lump sum transfers are not available, and if the government itself computes a positive NPV, then it might be sensible to mandate the necessary mitigation actions. Such a mandate would, of course, be in line with the common application of building codes applied in many countries.

To be clear, there are many plausible explanations for the low observed mitigation rates, including behavioural factors, loan market imperfections, the existence of subsidised insurance and finally a dependence on disaster relief. It is noteworthy that most U.S. households also fail to carry out NPV-positive investments in energy efficiency, even though the availability of disaster relief is not a relevant factor (see Jaffee et alFootnote 48). This suggests that disaster relief may not be a primary factor in explaining the failure to mitigate against natural disaster risks.

Expanding ex ante insurance when post-disaster relief is a leaky bucket

In comparing the costs of government relief with ex ante insurance, it is useful to distinguish three classes of government disaster relief:

-

i)

emergency responses that include immediate medical aid, temporary food and shelter, and rebuilding infrastructure for communications and travel;

-

ii)

compensation for loss of life or injury as illustrated by the U.S. 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund;

-

iii)

longer-term grants and loans provided to rebuild private property, primarily residential and commercial structures.

In our view, the policy issues raised by these categories are quite different and it is best to make our positions explicit at the outset.

We regard the emergency responses as the category where the ex post solution of government aid applies directly. We cannot imagine a situation in which a decision would be made to reduce government expenditures for medical aid and temporary food and shelter, or not to rebuild the public infrastructure. Indeed, the uniform U.S. outcry against FEMA following Katrina and against congressional inaction following Sandy was that they did too little, not that they did too much. While insurance might in principle provide financial compensation for the emergency injuries and dislocations created by catastrophic events, it is a physical response, not financial compensation, that is immediately required.Footnote 49 Based on data provided by Cummins et al.,4 approximately three-quarters of the total U.S. government disaster provided between 1989 and 2008 was provided by FEMA as emergency aid. So a large part of the government's disaster aid can be motivated by an ex post welfare criterion.

Government compensation for loss of life and injury, as illustrated by the U.S. 9/11 Victim's Compensation Fund, appears primarily to arise from losses created by war or war-like attacks. U.S. government insurance was also provided with no charge during World War II against private losses that would arise from attacks on the U.S. mainland. It seems clear that a sense of national unity in the face of an enemy attack was an important motivation for both war-time insurance and the 9/11 compensation fund.Footnote 50 A similar sense of national unity has been observed across Europe with respect to the creation of government insurance plans for protection against terrorist attacks (see OECDFootnote 51). However, there is no evidence of an expansion of such compensation plans to natural disasters in either the U.S. or Europe. As a result, the following analysis of government disaster relief and insurance does not include victim compensation funds.

This leaves the government disaster programmes that provide grants and aid to rebuild structures or re-establish businesses or to aid the agricultural sector. The Cummins et al.4 data indicate that approximately one-quarter of the total U.S. government disaster aid provided between 1989 and 2008 came from such agencies.Footnote 52 There is also the FEMA Individual Assistance (IA) programme that provides aid up to US$31,900 for temporary housing, home repairs and certain other non-housing-related costs (see Michel-KerjanFootnote 53). For all these expenditures, ex ante insurance can be considered a possible substitute for ex post disaster aid. We now discuss the implications regarding government policy for disaster relief.

Constructive and destructive insurance markets

As discussed in the previous section, the welfare role of insurance ranges from an important and constructive risk-sharing role under an ex ante criterion to a minimal and even negative role under a strict ex post criterion. The ex post view, however, assumes that lump sum transfers can be made without cost. In this section, we take up the second-best question of what might be the proper role of insurance when it is assumed that lump sum transfers are costly—sometimes described as making transfers with a leaky bucket. To simplify the discussion, we assume that the costs of lump sum transfers rise with the amount of the transfers, creating, in effect, a maximum amount for such transfers. Recalling that our discussion here applies primarily to property and business interruption insurance, we will simply assume that this maximum has been reached with the actual government expenditures observed in recent catastrophes. The key question is then whether an active role for insurance markets can be welfare enhancing under this condition.

As a first step in our analysis, we note that the example used in the previous section in some ways underplays the role of ex ante insurance. In that example, both agents have the same endowments in both states; so if they had the same beliefs and the same attitudes to risk, the ex ante optimal amount of insurance would be zero in any case. But suppose now that individual endowments in the two states are markedly different. Suppose, to take the extreme case, that a catastrophe is bound to occur, but we do not know which agent will be affected. For example, suppose that the {state 1, state 2} outcome for agent A is {0, 1}, while the outcome for agent B is {1, 0}. Then as per the Samuelson and Borch theorem stated earlier, if the individuals are otherwise alike, including identical beliefs and risk attitudes, then they will both fully insure, possibly through a mutual insurance contract. The insurance outcome would then be {½, ½} for both individuals.

Suppose now that their beliefs differ slightly. They will still insure, just not fully. If ex post lump sum transfers are costly, then relying only on an ex post relief system could easily lead to a worse outcome than the outcome achieved with ex ante insurance. This situation is more likely, the more skewed are the state-dependent endowments of the agents. Hence, insurance could well improve the ex post welfare, albeit just not to the first-best situation available from unlimited lump sum transfers.

On the other hand, it is also easy to generate situations in which insurance moves the agents away from the ex post optimum. Here, consider a case in which the {state 1, state 2} endowments are initially {½, ½} for both individuals, and suppose this is an ex post optimum. But now allow an insurance market to exist on an event that does not directly affect either agent. If the agents have differing subjective probabilities of the event, they may well take positions in the insurance market, the optimist (that the event will not occur) being the protection seller and the pessimist being the protection buyer. Ex post, there will be a settlement in one direction or the other, and this will necessarily move the agents away from the ex post optimum. And if lump sum transfers are not available, the agents would have been better off on an ex post basis if the insurance market had not existed.

Insurance contracts with or without an insurable interest

The likelihood that insurance will provide constructive ex post benefits is enhanced if the market requires an insurable interest. An insurable interest is defined here to mean that the protection buyer is exposed to an underlying risk, and that the insurance protection reduces this risk, ideally to zero. Thus, by definition, insurance that requires an insurable interest can only serve to reduce the ex post exposure of the protection buyer. It appears that most insurance policies purchased from chartered insurers require an insurable interest as a means to protect the insurer against the moral hazard that the insuree might try to profit by intentionally creating the insured event. The conclusion is that insurance markets that require an insurable interest are likely to serve as a good substitute for lump sum government transfers as a mechanism to move the economy towards its ex post social optimum.

On the other hand, financial markets now trade risk transfer instruments, such as credit default swaps (CDS) or indexed catastrophe bonds, that typically do not require an insurable interest. Participants in the markets for these instruments may hold very different subjective probabilities of the likelihood of the underlying event, and may therefore take very large and opposite positions as protection buyers and sellers. As an example, it appears that by late 2006, there had developed two very different views about the likely collapse of the market for U.S. subprime mortgages, with one view believing the subprime market would continue to provide high returns, and the other view believing a major collapse was imminent. The result was a very large open interest in a wide range of CDS contracts, and very large financial transfers to the protection buyers when the collapse did occur (see Stanton and WallaceFootnote 54). The overall conclusion is that, under these circumstances, an insurance market can move the economy to a position of lower ex post welfare.Footnote 55

Indexed catastrophe bonds provide a good example of a risk-transfer instrument that may be either constructive or destructive with respect to the attainment of an ex post optimum. These bonds will represent an insurable interest to the extent they allow insurers or reinsurers to hedge catastrophic risks in their portfolio, and to this extent they should be welfare enhancing. It does appear that most current issuers of catastrophe bonds do fall into this constructive category. However, the secondary trading markets for these bonds and similar instruments are becoming more liquid with the entry of some large hedge funds, and this could allow traders to take speculative positions as protection buyers or sellers where they believe they have more accurate information than the overall market regarding the likelihood of the event.

The positions of the U.S. insurer American International Group (AIG) during the subprime boom and crash provide a useful example of both constructive and destructive insurance. On the constructive side, AIG owned and still owns a chartered U.S. private mortgage insurer subsidiary, United Guaranty. United Guaranty operates as a monoline insurer, offering coverage against the risk of default by single-family mortgages. While United Guaranty suffered significant losses as a result of the subprime crash, it remains solvent and is writing policies today. On the destructive side, AIG also owned a Financial Products subsidiary that wrote credit default swaps against subprime mortgage securities. It was this subsidiary that required a large government bailout when the firm was no longer able to meet the margin calls that were supposed to control the counterparty risk on the swap contracts.

The special case of government insurance

As noted earlier, the available insurance programmes for catastrophic risks are now commonly governmental, quasi-public or based on government reinsurance, and we see no immediate prospects for the re-emergence of private insurance markets for these risks.Footnote 56 While an evaluation of these government insurance programmes is beyond the scope of this paper, we offer several comments on how the government affiliation of these programmes affects their impact on the ex post social welfare:

-

i)

These programmes generally require an insurable interest in the property being insured, and in this sense are in the class of constructive insurance.

-

ii)

The programmes vary widely in how the probabilities of the insured event, as embedded in the quoted insurance premiums, compare with the subjective probabilities of the consumers who may purchase the insurance. As one example, the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) offered subsidised premiums on many risks, thus creating an incentive for families to locate in risky locations, and with the result that close to a US$20 bn transfer was required from the U.S. Treasury to the NFIP to allow it to pay the many claims from Katrina (see Michel-KerjanFootnote 57). It would thus appear an open question whether the NFIP was a net positive or negative factor in moving the economy closer to an ex post optimum. It is therefore noteworthy that the U.S. Biggert-Waters Act of 2012 requires the replacement of subsidised premiums with risk-based premiums as a condition for the most recent five-year NFIP renewal (see National Association of Insurance CommissionersFootnote 58). On the other side, the U.S. California Earthquake Authority currently bases its premiums on the cost of reinsuring the risk, and it appears that the resulting premiums imply event probabilities far higher than the subjective probabilities of most California homeowners. The result is a very low take-up rate. While this may not create significant costs, it clearly limits the impact of the programme in moving California homeowners to a better ex post position.

-

iii)

In view of the low take-up rates observed for both U.S. earthquake and flood insurance, there are proposals that would require all homeowners to purchase such insurance (see KunreutherFootnote 59). Assuming that the event probabilities embedded in the quoted premiums are no higher than the subjective probabilities held by the consumers, such a mandate could well be ex post welfare enhancing given a limitation on lump sum transfers.Footnote 60 On the other hand, if the government insurance premiums are higher than consumers believe are warranted based on their subjective probabilities—for example, as appears the case with the California Earthquake Authority—the programme may not be ex post welfare enhancing.

Concluding comments

The important and expanding role of post-disaster government aid around the world results from a broad range of social, political and economic factors. The social factors primarily reflect the basic human instinct, fortunately still alive and well, to help people who face unexpected disasters. The political factor arises first because government is a natural mechanism to provide the humanitarian response—to control the free rider problem if nothing else—but also because it appears politicians benefit from being seen as the providers of such aid. The question “who should pay” may also arise as part of the political dialogue. For example, if the answer is that those in hazard-prone areas should pay for their own losses, then the government may require that insurance (public or private) be purchased in those areas.

Whatever the source, the rapidly expanding dollar size of governmental post-disaster relief now confronts the budgetary and fiscal mandate realities in many countries to reduce government expenditures. It is thus valuable at this time to review the fundamental welfare economics of post-disaster government aid and to reconsider the private market insurance and mitigation options that may be available to reduce these government expenditures.

The starting point for our analysis of the welfare economics of post-disaster government aid is the distinction between an ex ante and an ex post welfare criterion. The ex ante criterion reflects the traditional view of the risk-sharing benefits provided by well-functioning insurance markets, following the literature initiated by Arrow.Footnote 61 As long as all individuals and entities in the economy maintain and act on the same subjective probability for each catastrophic event, risk-sharing through insurance markets should remove the elements of idiosyncratic loss that might otherwise motivate government post-disaster aid. To be clear, there will still be a role for emergency government responses that include medical aid and temporary food and shelter, but large-scale government compensation for physical losses could be considered unnecessary.

The alternative ex post welfare criterion arises once it is recognised that individuals and entities may maintain quite different subjective probabilities for the various catastrophic events. An immediate result is that the insurance purchases by individuals will generally differ, and potentially differ quite significantly, from the amounts they would have purchased in a world in which there was a single shared subjective probability for the event. In particular, the optimists (with relatively low subjective probabilities) will tend not to buy insurance, and quite possibly could become protection sellers, depending on the available markets. Thus, when an actual event occurs, these individuals will be underinsured, and a system of ex post lump sum relief may be welfare enhancing, assuming there are no dead-weight costs associated with such government transfers.

The reality, of course, is that government transfers may entail significant costs, and thus second-best solutions must be considered. Second-best evaluations are necessarily complex and will depend importantly on why the individuals and entities in the economy maintained differing subjective probabilities. One explanation is behavioural. Specifically, it appears that some individuals will maintain subjective probabilities that are simply unreasonably low. In this case, a welfare improvement might be attained by providing such individuals with better information, or otherwise inducing or requiring them to purchase appropriate amounts of insurance.

In this paper, however, we focus on the case where the differences in subjective probabilities are fundamental and do not arise from behavioural biases. As discussed in the third section, including the examples from catastrophe bond spreads and Dutch flooding estimates, differing subjective probabilities exist for major catastrophic events. In this case, an evaluation of second-best solutions may depend on the role played by insurable interests in the functioning of the insurance markets. In cases where an insurable interest is a requirement to purchase insurance, risk transfer through insurance markets may systematically reduce the need for post-event government aid, and a requirement for individuals to purchase such insurance could be welfare enhancing as a second-best outcome (their low subjective probabilities notwithstanding).

On the other hand, there may also be cases where insurable interests are not required and insurance market trades by individuals and entities arise solely from the differing subjective probabilities. In this case, the gains and losses created by the actual event outcome can be welfare diminishing. The policy conclusion can then include actions to close or limit the insurance markets in order to minimise the need for offsetting post-disaster government aid.

The possible opportunities for individuals and entities to undertake cost-effective actions to mitigate the underlying risks raises another level of complexity with regard to the interaction with insurance markets, government disaster aid and behavioural factors. While insurance markets with risk-based insurance premiums will provide the correct incentives for mitigation activity, subsidised government insurance markets may actively reduce the economic benefits of mitigation and thus reduce the amount of mitigation that is carried out. In a similar fashion, through the Samaritan's dilemma, post-disaster government aid may reduce the incentive to carry out mitigation activities. Finally, behavioural underestimates of the event probabilities can also lead to a reduction in mitigation activity. Government policies must be carefully defined to deal with each of these market failures in the most effective manner.

Notes

See Jaffee and Russell (1997) for further discussion. Many U.S. hurricane risks are now insured through public/private partnerships such as the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund. At the same time, lines such as commercial flood risks and related business interruption insurance are commonly available through private insurers. See OECD (2005) and OECD (2008) for the specific catastrophe lines in a wide range of OECD countries.

In particular, the standard policy of the California Earthquake Authority (CEA) has a 15 per cent deductible, and with standard mitigation actions (bolting homes to their foundations and using plywood to create shear walls), it is unlikely a house will suffer damages above 15 per cent of the insured value. The CEA has also introduced a policy with a 10 per cent deductible, but few California homeowners have been attracted to it, presumably because the premiums are substantially higher.

This problem is discussed in the papers of Diamond (1967), Dreze (1970), Feiger (1976), Guesnerie and de Montbrial (1974), Hammond (1981), Harris (1978), Mirrlees (1974) and Starr (1973) among others. More recently, it has been discussed by Adler and Sanchirico (2006) and Fleurbaey (2010).

The use of credit default swaps (CDS) by certain investors to profit if the subprime housing boom were to collapse provides a good example of using insurance contracts to exploit a difference in opinion (and not to hedge an insurable interest). Further, some argue that this use of the CDS contracts deepened the subprime crisis and thereby enlarged the size of the required government bailouts. In a 2003 newsletter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett referred to such derivatives as “financial weapons of mass destruction”.

Note that these terms risk confusion as to when the welfare comparison is undertaken. In both cases the welfare comparisons and choices with respect to policy are made before it is known if a catastrophe has occurred. It is the level of individual welfare which is measured ex ante or ex post, not the time at which the evaluation takes place.

Arrow (1953, 1964, 1971).

For recent papers, see Brunnermeier and Xiong (2011) and Fedyk et al. (2012).

For a recent contribution on this topic in the finance literature, see Albagi et al. (2011).

Harris (1978) provides a simple comparison of the Starr and Hammond definitions for this example. Since preferences are time separable, it is possible to show all preferences over all feasible allocations by drawing two Edgeworth Bowley boxes with time 0 allocations on the vertical axis and state j, j=C, N allocations respectively on the horizontal axes. These two boxes must be of the same vertical height, since the same feasible quantity of X in time 0 is available regardless of which state occurs. By Starr's criterion, ex post efficient points must lie on the contract curve of each box at the same vertical height. By Hammond's criterion an ex post efficient point could lie on the contract curve of one of the state boxes, say state C, but (at the same vertical height) off the contract curve of the other state N. Any attempt to Pareto improve the welfare of both agents in state N would require a change in the allocation in time 0 which would reduce the welfare of one of the agents in State C, and is thus ex post efficient in the Hammond sense. This reduction in welfare in the other state is ignored by the Starr criterion which looks at efficiency state by state.

An intuitive explanation for the need for an additive linear (utilitarian) form for the social welfare function has been given by Adler and Sanchirico (2006). Assuming that all subjective probabilities are equal and equal to the social probabilities, the ex ante and ex post welfare functions are assembled from the same ingredients, the probabilities π j and the utilities U(X j i). But ex ante welfare assembles these ingredients by first forming the vector of expected utilities Vi=∑ j π j ui(x j )i =1 … n then evaluates, (W a (Vi)), whereas ex post welfare first evaluates the vector of utilities W p (ui(x j )) then applies the probabilities. Equality between these two concepts requires that the welfare function be additively linear.

Of course, emergency insurance for “roadside assistance” and “MedEvac” is available. However, these policies assume the infrastructure to provide the response remains operational. We know of no insurance lines that cover an infrastructure failure itself.

Hirshleifer (1953, 1955) discusses the U.S. World War II and Korean War insurance plans. In line with the discussion in this paper, he compares ex post compensation with an ex ante insurance plan. He favours the insurance plan to the extent that it applies risk-based pricing and thereby provides incentive for citizens to move themselves out of harm's way.

Using the Cummins et al. (2010) data, we compute that approximately 20 per cent of the U.S. government's disaster aid has come from the Small Business Administration (SBA) and United States Department of Agriculture (USAD) agencies. We estimate that including expenditures from HUD and other agencies would raise the total to perhaps 25 per cent. It is also important to note that a significant share of the U.S. federal government's disaster aid is a transfer to state and local governments to rebuild public infrastructure.

See Stulz (2010) for one of a number of recent papers that discuss the negative welfare consequences of credit default swaps.

In the U.S., the National Flood Insurance Program is fully governmental, the California Earthquake Authority quasi-public, and the federal Terrorism Risk Insurance Act provides government reinsurance. See OECD (2005, 2008) for discussions of the role of government catastrophe insurance in a range of OCEC countries.

It is also possible under these circumstances that markets for private flood and earthquake insurance might again become operative.

References

Adler, M.D. and Sanchirico, C.W. (2006) ‘Inequality and uncertainty: Theory and legal applications’, University of Pennsylvania Law Review 155 (2): 279–377.

Albagi, E., Hellwig, C. and Tsyvinski, A. (2011) ‘A theory of asset prices based on heterogeneous information’, Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 1827; New Haven: Yale University.

Arrow, K.J. (1953) ‘Le Rôle des Valeurs boursières pour la Repartition la meilleure des Risques’, Econometrie, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, pp. 41–48. Translated in to English in The Review of Economic Studies (1964).

Arrow, K.J. (1964) ‘The role of securities in the optimal allocation of risk-bearing’, The Review of Economic Studies 31 (2): 91–96.

Arrow, K.J. (1971) Essays in the Theory of Risk-Bearing, Chicago: Markham.

Bantwal, V. and Kunreuther, H. (2000) ‘A cat bond puzzle’, Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets 1 (1): 76–91.

Borch, K. (1962) ‘Equilibrium in a reinsurance market’, Econometrica 30 (3): 424–444.

Botzen, W.J.W., Aerts, J.C.J.H. and van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. (2009) ‘Dependence of flood risk perceptions on socioeconomic and objective risk factors’, Water Resources Research, 45 (10): 1–15.

Brattberg, E. and Rhinard, M. (2012) The EU and US as International Actors in Disaster Relief, College of Europe, Bruges Political Research Paper #22, from www.aei.pitt.edu/33459/1/wp22_Brattberg_Rhinard.pdf.

Broome, J. (1989) ‘An economic Newcomb problem’, Analysis 49 (4): 220–222.

Brunnermeier, M.K. and Xiong, W. (2011) A Welfare Criterion for Models with Heterogeneous Beliefs, Princeton University working paper.

Buchanan, J.M. (1975) ‘The Samaritan's Dilemma’, in E.S. Phelps (ed.) Altruism, Morality, and Economic Theory, New York: Russell Sage foundation, pp. 71–85.

Comerio, M.C. (1998) Disaster Hits Home, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cummins, J.D., Suher, M. and Zanjani, G. (2010) ‘Federal financial exposure to natural catastrophe risk’, in D. Lucas (ed.) Measuring and Managing Federal Financial Risk. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 61–92.

Debreu, G. (1959) The Theory of Value: An Axiomatic Analysis of Economic Equilibrium, New York: Wiley.

Diamond, P.A. (1967) ‘Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility: Comment’, The Journal of Political Economy 75 (5): 765–766.

Dixon, L. and Stern, R. (2004) Compensation for Losses from the 9/11 Attacks, Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Dreze, J. (1970) ‘Market allocation under uncertainty’, European Economic Review 2 (2): 133–165.

European Commission, Commissioner Georgieva (2012) ‘New Legislation on Disaster Response Capacity’, from www.ec.europa.eu/commission_2010-2014/georgieva/hot_topics/european_disaster_response_capacity_en.htm.

European Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Directorate-General (2012) ‘Disaster Risk Reduction’, from www.ec.europa.eu/echo/policies/prevention_preparedness/dipecho_en.htm.

Fedyk, Y., Heyerdahl-Larsen, C. and Walden, J. (2012) Market Selection and Welfare in a Multi-asset Economy, working paper, from www.faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/walden/HaasWebpage/marketselection.pdf.

Feiger, G. (1976) ‘Some remarks on efficiency when anticipations are diverse’, PhD Thesis, Harvard University, Chapter 5.

Fellowes, M. and Liu, A. (2006) ‘Federal allocations in response to Katrina, Rita, and Wilma: An update’, Metropolitan Policy Program, The Brookings Institution, 21 August 2006.

Fleurbaey, M. (2010) A Defense of the Ex-post Evaluation of Risk, working paper, University of Paris Descartes.

Froot, K.A. (2001) ‘The market for catastrophe risk: A clinical examination’, Journal of Financial Economics 60 (2–3): 529–571.

Frydman, R., O’Driscoll, P. and Schotter, A. (1982) ‘Rational expectations of government policy: An application of Newcomb's problem’, Southern Economic Journal 49 (2): 311–319.

Guesnerie, R. and de Montbrial, T. (1974) ‘Allocation under uncertainty: A survey’, in J. Dreze (ed.) Allocation under Uncertainty, London: Macmillan, pp. 53–70.

Hammond, P. (1981) ‘Ex-ante and ex-post welfare optimality under uncertainty’, Economica 48 (191): 235–250.

Harris, R. (1978) ‘Ex-post efficiency and resource allocation under uncertainty’, The Review of Economic Studies 45 (3): 427–436.

Harris, R. and Olewiler, N. (1979) ‘The welfare economics of ex-post optimality’, Economica 46 (182): 137–147.

Hirshleifer, J. (1953) ‘War damage insurance’, The Review of Economics and Statistics 35 (2): 144–153.

Hirshleifer, J. (1955) ‘Compensation for war damage: An economic view’, Columbia Law Review 55 (2): 180–194.

Holden, R.J., Bahls, D. and Real, C. (2007) ‘Estimating economic losses in the bay area from a magnitude 6.9 earthquake’, Monthly Labor Review 130 (12): 16–22.

Jaffee, D. and Russell, T. (1997) ‘Catastrophe insurance, capital markets, and uninsurable risks’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 64 (2): 205–230.

Jaffee, D., Stanton, R. and Wallace, N. (2011) Energy Efficiency and Commercial-mortgage Valuation, Working paper, from www.faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/jaffee/research.htm.

Kolm, Serge-Christophe (1998) ‘Chance and justice: Social policies and the Harsanyi, Vickrey, Rawls problem’, European Economic Review 42 (8): 1393–1416.

Kunreuther, H. (1978) Disaster Insurance Protection: Public Policy Lessons, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Kunreuther, H. (1996) ‘Mitigating disaster losses through insurance’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 12 (2–3): 171–187.

Kunreuther, H. (2006) ‘Disaster mitigation and insurance: Learning from Katrina’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604 (1): 208–227.

Kunreuther, H. (2008) ‘Reducing losses from catastrophic risks through long-term insurance and mitigation’, Social Research: An International Quarterly 75 (3): 905–930.

Kunreuther, H. and Pauly, M. (2004) ‘Neglecting disaster: Why don’t people insurance against large losses’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 28 (1): 5–21.

Kunreuther, H. and Pauly, M. (2006) ‘Rules rather than discretion: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 33 (1–2): 101–116.

Kunreuther, H. and Michel-Kerjan, E. (2009) ‘The development of new catastrophe risk markets’, Annual Review of Resource Economics 1 (1): 119–139.

Kunreuther, H., Pauly, M. and McMorrow, S. (2013) Insurance and Behavioral Economics: Improving Decisions in the Most Misunderstood Industry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kydland, F.E. and Prescott, E.C. (1977) ‘Rules rather than discretion: The inconsistency of optimal plans’, Journal of Political Economy 85 (3): 473–491.

Michel-Kerjan, E. (2010) ‘Catastrophe economics: The national flood insurance program’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24 (4): 165–186.

Michel-Kerjan, E. (2013) Have We Entered an Ever-Growing Cycle on Government Disaster Relief, Presentation to U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 14 March 2013.

Michel-Kerjan, E. and Volkman Wise, J. (2011) ‘The Risk of Ever-Growing Disaster Relief Expectations’, from www.nber.org/~confer/2011/INSf11/INSf11prg.html.

Mirrlees, J.A. (1974) ‘Notes on welfare economics, information and uncertainty’, in M. Balch, D. McFadden and S. Wu (eds) Essays on Economic Behavior under Uncertainty, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 243–258.

Moss, D. (1999) ‘Courting disaster? The transformation of federal disaster policy since 1803’, in K. Froot (ed.) The Financing of Catastrophe Risk, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 307–362.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2012) ‘Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform and Modernization Act of 2012’, from http://www.naic.org/documents/cipr_overview_2012_flood_reauthorization.pdf.

OECD (2005) Terrorism Risk Insurance in OECD Countries, Policy Issues in Insurance #9, from www.oecd.org/insurance/insurance/terrorismriskinsuranceinoecdcountries-policyissuesininsurancen9-oecd.htm.

OECD (2008) Financial Management of Large-Scale Catastrophes, Policy Issues in Insurance #12, from www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/financial-management-of-large-scale-catastrophes_9789264041516-en.

Pomeroy, G. (2010) ‘Testimony before the House Committee on Financial Services, Hearings on Approaches to Mitigating and Managing Natural Catastrophe Risk, H.R. 2555, The Homeowners’ Defense Act.

Priest, G. (2003) ‘Government insurance versus market insurance’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 28 (1): 71–80.

Risk Management Systems (2004) ‘The Northridge, California earthquake, 10-year retrospective’, revised 13 May 2004.

Samuelson, P.A. (1967) ‘General proof that diversification pays’, The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2 (1): 1–13.

Stanton, R. and Wallace, N. (2011) ‘The bear's lair: Indexed credit default swaps and the subprime mortgage crisis’, The Review of Financial Studies 24 (10): 3250–3280.

Starr, R. (1973) ‘Optimal production and allocation under uncertainty’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 87 (1): 81–95.

Stulz, R. (2010) ‘Credit default swaps and the credit crisis’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24 (1): 73–92.

Swiss Re (2002) Floods are Insurable, Focus Report, 2002, from www.media.swissre.com/documents/pub_floods_are_insurable_en.pdf.

Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank the journal's referees, seminar participants at the National Bureau of Economic Research and at Pennsylvania State University, and Peter Hammond for helpful comments that improved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

The Samaritan's dilemma and conflicts with the ex post welfare criteria

The desire to provide help to victims of disaster is a natural part of the human condition, but, unfortunately, such Samaritan aid inevitably interferes with the ex ante incentives of the victims to help themselves (Buchanan7). This gives rise to a problem of time inconsistency. As Kunreuther and PaulyFootnote 62 note, although this concept was developed by Kydland and Prescott9 to deal with the design of macroeconomic policy, time inconsistency is a ubiquitous policy problem; indeed Kydland and Prescott used the problem of the design of a programme of flood relief to motivate their treatment of monetary policy.

As originally set out by Buchananin, the Samaritan's dilemma can be viewed as a 2 × 2 simultaneous matrix game with the payoffs shown in Table A1.

Here player A is a potential Samaritan, player B is in need of help. A has two strategies, A1, “help”, say, by giving a money transfer and A2, “do not help”. B has two strategies, B1 “work”, and B2 “don’t work”. A's payoffs are listed first.

It is easy to see that the game has one Nash equilibrium in pure strategies, A1, B2. Buchanan proposes various versions of the game, but in general the outcome is the same. Thinking strategically, the victim, knowing that help is coming, shirks, thus failing to help himself.

The essence of this game can be transferred to the policy design problem for ex post catastrophe relief. To make the link to the work of Kydland and Prescott,9 consider the payoffs to a government which is considering A1 a policy of providing a finite, budget-constrained amount of relief, or alternatively A2 a policy of no relief.

As in the work of Kydland and Prescott,9 the efficacy of these two policies depends on the expectations of the victims. When the victims expect that the government will not undertake relief, expectations B1, they will themselves mitigate the potential loss. But if they expect the government to provide relief, expectations B2, they have no incentive to mitigate, and will not do so. Looking at the payoffs to the government we again have a 2 × 2 matrix of payoffs. We assume that the government is concerned with the welfare of the victims, with payoffs as in Table A2.

The worst outcome (1 on a scale from 1 to 4 where 4 is the best) is A2 B2 in which the citizens make no plans for the disaster and the government provides no relief. The best outcome is A1 B1 in which the government provides its budget limited relief to top up the private mitigation efforts to the extent that they did not fully protect against the flood.

The ordering of the other two outcomes, A2 B1 (no government help but private citizens mitigate) and A1 B2 (government help but no private mitigation) depends on the effectiveness of private mitigation vs the amount of relief which a budget-constrained government can afford. The interesting case is the ranking in Table A2 in which private mitigation leads to a better outcome than a government can provide with limited relief.

This case is an example of a decision-theoretic problem called Newcomb′s problem (see BroomeFootnote 63). This problem arises when a decision maker must make one of several decisions in such a way that its payoff is affected by whether or not its action was anticipated by another rational agent with good predictive powers. In this case, as here, no one uniquely best rational course of action exists.

To see this, we ask what government policy should be in this case? If we assume that individuals correctly anticipate government action, then if the government provides relief, it will have been expected, and no mitigation will have been undertaken. This outcome is worse than the government doing nothing, since in this case flood losses will have been reduced by the actions of the potential victims. This calls for a rule of “do nothing”.

However, this framework permits another way of reasoning. Before the government acts, people will have already formed their expectations, and will either have mitigated or not. No matter which, the results of providing relief are better than the results of not providing relief. Therefore the government should provide relief.

The optimal rule a la Kydland and Prescott is a rule of “no help”. But having adopted such a rule, with the mitigation in place, it would seem appropriate to break the rule and provide relief. As Frydman et al.Footnote 64 have argued, the first casualty of this time inconsistency problem is rational expectations itself. Since there is no obvious best course for the government, it is not possible for the agents to have rational expectations regarding it.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaffee, D., Russell, T. The Welfare Economics of Catastrophe Losses and Insurance. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 38, 469–494 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2013.17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2013.17