Abstract

In this paper, we propose to use insurance stock returns as an indicator of insurance activities, and apply a dynamic panel technique to examine the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. Our empirical results show that after we control for the variations of market index returns, there is a significantly positive relationship between insurance stock returns and future economic growth. Furthermore, we also investigate how law environment and governance quality affect the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. The empirical results are consistent with our expectation that a well-defined law environment and governance quality facilitate the functioning of insurance companies, and strengthen the role of insurance in economic growth. We find generally that the effect of law and governance on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth is more significant in developed markets than in emerging markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A large body of literature emphasises the importance of insurance development in promoting economic growth, given the fact that insurance can not only facilitate the economic transactions through risk transfer and indemnification, but also promote financial intermediation.Footnote 1 For instance, based on the Solow-Swan neoclassical growth model, Webb et al.Footnote 2 theoretically examined the relationship between insurance activity and economic growth. With a Cobb-Douglas production function, the model predicts that insurance and banking can facilitate the efficient allocation of capital and promote economic growth. ArenaFootnote 3 has an empirical investigation of the role of insurance by employing Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) models on a dynamic panel data set of 56 economies for the period from 1976 to 2004. They find both life and non-life insurance have significantly positive effects on economic growth. Haiss and SümegiFootnote 4 have a literature review about theoretical and empirical research about the role of insurance.

In the previous literature, insurance market size is a commonly used indicator of insurance activity and is usually defined as the gross direct premiums written.Footnote 5 Browne and KimFootnote 6 and Ward and Zurbruegg1 argue that the total written premiums do not account for different market forces and regulatory effects on pricing, and cannot accurately measure total insurance market output. Furthermore, in some countries insurance pricing may be subject to some restrictions (e.g. Japan), and some insurances coverage is compulsory (e.g. automobile insurance), therefore insurance market size that relies on the aggregate size of insurance premiums does not measure insurance functioning in a direct way.

In this paper, we propose to use insurance stock returns as an indicator of insurance activities, and examine the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. It has been well documented in the previous literature that stock returns are correlated with future real activity, see for example FamaFootnote 7 and Schwert.Footnote 8 By regressing current production growth on previous stock returns, they show that monthly, quarterly and annual stock returns can predict the future production growth rate. Recently, Cole et al.Footnote 9 propose to use banking stock returns to measure financial development, and they show that current banking returns can predict future economic growth. In this paper, we follow the previous literature, and use insurance stock returns to proxy insurance activities, as the functioning of insurance companies can be reflected in their stock prices.

A dynamic panel data study is applied to examine the link between the role of insurance and economic growth for 38 countries, including 23 developed countries and 15 emerging countries, covering a period between 1982 and 2008. Given that the impacts of insurance on economic growth might be different between life and non-life insurance, and between developed markets and emerging markets,3 we accordingly divide our sample into nine groups. More specifically, the groups of insurance sectors are life insurance sector, non-life insurance sector and all insurance sectors, while the groups of markets are developed markets, emerging markets and all markets. Our empirical results show that for all nine groups after we control for the variations of market index returns, there is a significantly positive relationship between insurance excess returns and future economic growth.

Furthermore, we investigate how country-specific law environment and governance quality affect the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. The results for all insurance sectors are consistent with our expectation that a well-defined law and governance environment facilitates the functioning of an insurance company, and strengthens the role of insurance in economic growth. Moreover, we find generally the effect of law and governance on the role of insurance is more significant in developed markets than in emerging markets.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. A brief literature review is provided in the next section. Then the subsequent section presents the methodology for our analysis and gives the empirical predictions about the effect of the law environment and governance quality on the role of insurance, and the section after that gives the data as well as summary statistics. The penultimate section reports the empirical results. Using the dynamic panel GMM estimation method, we find after we control for the variations of market index returns, there is a significantly positive relationship between insurance excess returns and future economic growth. We also investigate how country-specific law environment and governance quality affect the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. The empirical results show that well-defined law environment and governance quality facilitate the functioning of an insurance company, and strengthen the role of insurance in economic growth. Finally the last section concludes the paper.

Related literature

In the past literature, to investigate the relationship between insurance development and economic growth, several measures were used as proxies for insurance activities, for example:

(1) Total insurance premiums

In past insurance studies, total insurance premiums were the most accepted measures of insurance activities. For instance, using total written premiums and real GNP as the indicators for insurance and economic activities, respectively, Ward and Zurbruegg1 investigate the causal relationship between insurance industry development and economic growth using data for nine OECD countries over the period from 1961 to 1996. On the basis of Johansen's cointegration test, they find a long-run relationship is present for Australia, Canada, France, Italy and Japan. The Granger causality tests show that insurance market development leads economic growth for Canada and Japan, a bidirectional relationship for Italy, and no connection for the other six OECD countries, including Australia, Austria, France, Switzerland, U.K. and U.S. They argue that the different causal relationship between insurance and economic growth across countries might be due to their differences in risk attitudes, regulatory effects and insurance density.

Adams et al.Footnote 10 also use total insurance premiums as an indicator of insurance market activities and examine the dynamic relationship between banking, insurance and economic growth in Sweden over the period from 1830 to 1998. The cointegration and Granger causality tests show that it is banking development rather than insurance development that led economic growth in Sweden during the nineteenth century, with a reverse direction in the twentieth century. They conclude that the insurance market appeared to be driven by economic growth and not that the insurance market led economic development.

Several authors point out the shortcomings of using total insurance premiums as an indicator of total insurance market activity. For instance, Browne and Kim,6 and Ward and Zurbruegg1 argue that the total written premiums do not account for different market forces and regulatory effects on insurance pricing, and cannot accurately measure total insurance market output. As the impact of insurance on economic growth might be different between different insurance components such as life and non-life insurance,3 insurance premium components are used as the measures for insurance activity.

(2) Premium components

With a cross-sectional analysis of 45 countries for the years 1980 and 1987, Browne and Kim6 find that national income is positively correlated with life insurance consumption. Their results are also supported by OutrevilleFootnote 11 and Han et al.,Footnote 12 among which Outreville11 applies a cross-sectional study of 48 developing countries for the year 1986, and Han et al.12 apply a dynamic panel data analysis of 77 countries during the period between 1994 and 2005. Meanwhile, Ye et al.Footnote 13 find a number of socio-economic and market structure factors can influence foreign participation in life insurance markets based on 24 OECD countries during the period 1993–2000.

Webb et al.2 investigate the impact of banking and insurance activity (life and non-life insurance) on economic development. Using the three-stage-least-squares instrumental variable approach (3SLS-IV), the authors find that financial intermediation has a significant positive impact on economic growth. However, when splitting into three, non-life insurance lost its importance. All individual variables lost explanatory power when the interaction terms (bank and life insurance, or bank and non-life insurance) are included in their analysis, suggesting the existence of complementarities among financial intermediaries.

Using property-liability insurance (PLI) premiums as an indicator of insurance activity, Beenstock et al.Footnote 14 apply a pool data analysis with data covering 12 countries for the period from 1970 to 1981. The results show that higher interest rates tend to increase the PLI premiums. Then they have a cross-sectional study using data for 45 countries and find a significantly positive relationship between insurance consumption and economic growth.

The conclusion of Beenstock et al.14 is also supported by the empirical results of Outreville.Footnote 15 With a cross-sectional data of 55 developing countries for the years 1983 and 1984, Outreville15 finds there is a significant relationship between the PLI premiums and economic development.

Arena3 investigates the impact of the role of insurance (life and non-life insurance) on the economic growth of 56 countries for the period from 1976 to 2004. Using the GMM method for dynamic panel data model, the authors find that life insurance and non-life insurance both have significantly positive effects on economic growth. More specifically, the results are driven by high-income countries for life insurance, while for non-life insurance, the results are driven by both high-income and developing countries, with a larger effect in high-income countries.

Given that the net written premiums are available for a longer period than the gross in the United Kingdom, Kugler and OfoghiFootnote 16 use the net written premiums as an indicator of insurance activity and evaluate the long-run relationship between the insurance market and economic growth for the U.K. To avoid unreliable results that might be incurred by the aggregated data, they use nine components of insurance premiums including long term, motor, property, etc. The Johansen's cointegration tests show that for all insurance components, there is a long-run relationship between insurance market size and economic growth. The Granger causality tests show that the insurance premiums caused economic growth for eight out of nine insurance components and growth in GDP caused increased insurance premiums for only three cases.

Since in some countries the insurance pricing may be subject to some restrictions, insurance components that rely on insurance premiums do not measure insurance functioning in a direct way. Distinguishing our work from previous literature, in this paper we use insurance sector excess stock returns as proxies of insurance activities and apply a panel data technique to investigate the relationship between the role of insurance and economic growth.

Compared to insurance premiums, our method suffers the problem that it excludes the mutual sector from our sample, which in some countries is a major force of the insurance market. A mutual insurance company is operated on a mutual basis and its members are also its policyholders. Usually the mutual insurance company cannot raise money in the capital market, which restricts its ability to acquire capital. The mutual insurance sector plays a key role in the world insurance markets. According to the report of the International Cooperative and Mutual Insurance Federation, at the end of 2006 the mutual market share was 23.9 per cent. Of the largest 10 insurance countries, five of them have their mutual market shares exceeding 25 per cent, which are Germany (41 per cent), France (40 per cent), Japan (36 per cent), U.S. (30 per cent) and Spain (29 per cent). In this paper we use insurance stock returns as an indicator of insurance activity, with a focus on listed insurance companies only as a representative of the most publicly exposed and informative part of the insurance industry, without necessarily representing the whole insurance industry.

Furthermore, we investigate how the law environment and governance quality affect the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. In the past insurance studies, the law and governance measures are usually used as proxy for loss probability or insurance company insolvency and are included as the determinant of insurance consumption. For instance, Browne et al.Footnote 17 show that the form of legal system is an important factor in explaining the purchase of general liability insurance and motor vehicle insurance. Esho et al.Footnote 18 include the 50 point property rights index in their panel data study. The rights index was developed by Knack and KeeferFootnote 19 and constructed using some law and governance measures, including the general level of corruption, rule of law, state bureaucratic quality, the risk of contract repudiation and the risk of expropriation. Their empirical results show that there is a significantly positive correlation between insurance consumption and protection of property rights. Moreover, they find after controlling the variations of income and property rights, the legal origin of a country does not affect insurance demand.

Previous empirical studies have shown that a well-defined judicial system and high quality governance play important roles in facilitating financial intermediation and economic development.Footnote 20 However, to the best of our knowledge no one has examined how the law environment and governance quality affect the link between insurance development and economic growth. To deal with this issue, we include some interaction terms in the pool data analysis, which are constructed by multiplying the law and governance measures with insurance excess returns. The signs of the coefficient indicate whether the law and governance factors strengthen or weaken the link between the role of insurance and economic growth.

Methodologies and empirical predictions

Dynamic model of panel data

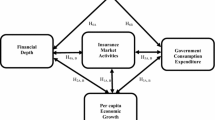

To analyse the dynamic relationship between the role of insurance and economic growth, similar to Arena3 and Cole et al.,9 we work with the following fixed-effect dynamic panel data model:

where i=country; t=time period; Y it =the GDP growth rate; X it =a set of explanatory variables, including Rm,i(t−1), Rn,i(t−1), representing market excess return and insurance sector excess returns, respectively, and law and governance interaction terms. η i =an unobserved country-specific effect, and ɛ it =the error disturbance.

In the model, the disturbance ɛ it is assumed to have finite moments and zero cross-correlation, and satisfies E(ɛ it )=E(ɛ it ɛ is )=0 for t≠s. As RoodmanFootnote 21 notes, the assumption of zero cross-correlation might hold if the time dummies are included into the regression. We follow Roodman's21 idea and add the time dummies into the regression, but to save space we do not report their coefficients. Finally we have the following standard assumption E(η i )=E(η i ɛ it )=0 and E(Yi1 ɛ it )=0 for i=1, ⋯, N and t=2, ⋯, T.

Eq. (1) is a dynamic model of panel data for it includes a lagged dependent variable as one regressor, which is correlated with the disturbance. By taking the first difference of Eq. (1), we can remove the country-specific effect η i and produce the following equation,

where ΔY it =Y it −Yi(t−1), ΔX it =X it −Xi(t−1) and Δɛ it =ɛ it −ɛi(t−1). Arellano and BondFootnote 22 design a GMM estimator for α and β. In particular, they use the lagged level of the dependent variable as the instruments since ɛ it is uncorrelated over time, which implies the follow equation,

Therefore the instruments can be written as

and α and β can be estimated using the following moment conditions:

where Δɛ i =[Δɛi3, Δɛi4, ⋯, Δɛ iT ].

However, as Ahn and SchmidtFootnote 23 point out, the first-differenced GMM estimator neglects information about the levels of the dependent variables. On the basis of the first-differenced GMM estimator, Arellano and Bover,Footnote 24 and Blundell and BondFootnote 25 propose the system-GMM estimator and add lagged first differences of Y it as instruments in the level equation, that is

Monte Carlo simulations show the system-GMM estimator performs more efficiently than the first-differenced GMM estimator. The system-GMM estimator is used in this paper to estimate Eq. (1) as it can utilise more data information and is a more efficient estimator.Footnote 26

As Doornik et al.Footnote 27 and Cole et al.9 point out, there exists an overfitting problem if too many instrument variables are used in the estimation process, especially when the regressors are endogenous. Therefore in this paper we do not use the full history of lagged dependent variables as instruments as in Eq. (4), but only include eightFootnote 28 lags of dependent variables as instruments for the moment restriction (5). Moreover, to account for the endogeneity problem, we follow Arena3 and use the legal origin code as instruments of stockmarket variables, and religious composition as insurance instruments. We get the data of legal origin code and religious composition from La Porta et al.Footnote 29

As noted by Windmeijer,Footnote 30 the two-step GMM estimator might be misleading in asymptotic inferences. Arellano and Bond,22 and Blundell and Bond25 suggest using the one-step GMM estimator to conduct inferences on the coefficients as the one-step estimator is more reliable. Therefore in this paper we use the one-step GMM estimator to conduct our inference on the coefficients. To allow for heteroscedastic error terms, our analyses are based on robust standard error estimates.

However, the asymptotic distribution of Sargan test statistics is unknown for the robust model, as the statistics are chi-squared distributed only in the case of homoscedasticity. The Sargan test is efficient for the two-step GMM estimator and the two-step Sargan test is generally recommended for inference on model specification. Therefore we follow Roodman21 and conduct two-step GMM procedures to compute the Sargan test statistics. The results show that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the moment restrictions are valid. To save space we do not report the Sargan test statistics, but only report results of the second-order autocorrelation to assess whether the estimates are consistent.

Empirical predictions about the law and governance interaction terms

The law and governance measures are included in our analysis because of their potential influence on the role of insurance in promoting economic growth. The law measures used in this paper include the efficiency of judicial system (JUD), rule of law (RULE), corruption (COR), risk of expropriation (EXPR) and risk of contract repudiation (CONT), which are extracted from La Porta et al.Footnote 31 As La Porta et al.32 note, the efficiency of judicial system evaluates “the efficiency and integrity of the legal environment as it affects business, particularly foreign firms”. As the rights of both the insured and the insurer are well protected in an efficient legal environment, insurance companies can function better in a country with a more efficient and integrated judicial system. Therefore we expect the efficiency of judicial system could have a positive effect on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. Similarly we would expect positive effects of the other four law measures.

The governance indicators for each country used here are drawn from Kaufmann et al.,Footnote 32 and consist of voice and accountability (VA), political stability and absence of violence (PV), government effectiveness (GE), regulatory quality (RQ), rule of law (RL) and control of corruption (CC). We calculate each dimension by taking the average over the sample period.

As the VA indicator measures the citizen's freedom of expression, a higher degree of VA leads to a higher rate of conflict between the insurance companies and the insured, which in turn leads to higher costs for insurance companies and weakens the role of insurance in promoting economic growth. Thus we would expect the sign of the VA indicator to be negative.

However, we would expect a positive effect of political stability on the role of insurance in that a stable political environment helps insurance companies to operate in a safe and stable way, and strengthens their role in promoting economic growth. The other four dimensions of governance measures are related to legal enforcements, and therefore we also expect them to have positive signs.

Data

The data used in this study includes quarterly information of about 38 countries, covering a period between 1982 and 2008. We select the markets based on the data availability. Moreover, we omit those markets whose length of time series is less than 5 years. Table 1 lists the names of economies used in this study, including 23 developed countries and 15 emerging countries.

Our data is obtained from various sources, and their definitions and sources are provided in Table 2. Given that the impacts of insurance on economic growth might be different between life and non-life insurance, and between developed markets and emerging markets, we accordingly divide our sample into nine sample groups. Like Cole et al.9 we use overlapping annual data with quarterly observations. Table 3 presents some basic descriptive statistics.

For each sample group, we can find that compared to developed markets, emerging markets enjoy more rapid, but more volatile economic growth. For instance, in our data sample, the average GDP growth rate for developed markets is 2.9 per cent, with a standard deviation of 2.5 per cent and a range of −8.4 per cent to 14.6 per cent, while the average GDP growth rate for emerging markets is 5.7 per cent, with a standard deviation of 13.3 per cent and a range of −19.8 per cent to 278.2 per cent.

However, we find that emerging markets underperform developed markets with regards to the development of their stockmarkets and insurance markets. More specifically, for developed markets, the average market excess returns and insurance sectors returns are 4.2 per cent and 0.8 per cent, respectively, with standard deviations of 27.4 per cent and 37.8 per cent, and ranges of −109.8 per cent to 201.6 per cent and −202.2 per cent to 284.1 per cent. However, for emerging markets, the two average returns are −5.3 per cent and −6.3 per cent, respectively, with standard deviations of 33.9 per cent and 44.3 per cent, and ranges of −328.3 per cent to 96.3 per cent and −273.7 per cent to 162.0 per cent. We can also draw similar empirical conclusions for life and non-life insurance sample groups. The preliminary results suggest that the insurance market might play a different role in economic growth across developed markets and emerging markets.

Table 4 presents the correlation information between GDP growth rate and stock excess returns for each sample group. For developed markets, correlation between market excess returns and GDP growth rates are similar across different insurance sectors, all around 0.4. However, for emerging markets, the difference is large across different insurance sectors. More specifically, the correlation is 0.501 for the life insurance sector and is 0.011 for the non-life insurance sector. In terms of the correlation between insurance excess returns and GDP growth, the values are similar across different insurance sectors, around 0.25 for developed markets and around 0.3 for emerging markets. We also find a strong correlation between the insurance excess returns and market excess returns across different insurance sectors and different markets, and their values lie in the range from 0.418 to 0.547.

Empirical results

Tables 5, 6 and 7 show the predictive power of market excess returns and insurance excess returns for future economic growth. For each table, specification 1 gives the regression results of Eq. (1) when the explanatory variables are set to be market excess returns, while specification 2 reports the regression results of Eq. (1) when the explanatory variables are insurance excess returns. We find for all nine sample groups, the coefficients of both R m and R i are significantly positive, suggesting that market excess returns and insurance excess returns are positively related with the subsequent GDP growth rate. Specification 3 further reports the regression results when we include both R m and R i into our panel data analysis. We find for all nine sample groups, the coefficients of R m and R i are positive and statistically significant at the 10 per cent level. Therefore after controlling the variation of market excess returns, the insurance excess returns still have significant predictive power for the subsequent GDP growth rate.

In spite of being statistically significant, the size of R i is relatively small. However, as Arena3 states, the volatility of R i should be taken into account when we examine the economic effect of insurance activity. For instance, we find in specification 3 of Table 5, the coefficient of lag(R i ) for all markets is 0.010. As the standard deviation of insurance returns is 0.399 for all markets, the results suggest that an increase of one standard deviation in insurance returns leads to an increase of 0.40 per cent in GDP growth, which is economically significant. Similarly, for all insurance sectors, we can calculate an increase of one standard deviation of insurance returns leads to an increase of 0.19 per cent in GDP growth for developed markets, and 0.44 per cent for emerging markets. Similar analysis can be conducted for Tables 6 and 7. For the life insurance sector, we calculate that an increase of one standard deviation in insurance returns leads to an increase of 0.38 per cent in GDP growth for all markets, 0.20 per cent for developed markets, and 0.24 per cent for emerging markets. While for non-life insurance sector, we calculate that an increase of one standard deviation in insurance returns leads to an increase of 0.28 per cent in GDP growth for all markets, 0.12 per cent for developed markets, and 0.31 per cent for emerging markets.

Tables 8, 9 and 10 report the regression results of Eq. (1) when we include some law interaction variables in our analysis. The measures of judicial system used here include the efficiency of judicial system (JUD), rule of law (RULE), corruption(COR), risk of expropriation (EXPR) and risk of contract repudiation (CONT).

In Table 8, with respect to all insurance sectors, we find for developed markets, all the law interaction terms are significantly positive above the 10 per cent level except for the interaction term of corruption. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of those significant law interaction terms on economic growth are 0.68 per cent for JUD, 0.83 per cent for RULE, 1.89 per cent for EXPR, and 1.48 per cent for CONT. Therefore the risk of expropriation and risk of contract repudiation have a relatively higher impact on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth than other law variables. For emerging markets, only two out of five interaction terms, that is the risk of expropriation and the risk of contract repudiation are statistically significant above the 10 per cent level. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of these two law interaction terms on economic growth are 2.12 per cent for EXPR, and 2.64 per cent for CONT.

Table 9 presents the results for the life insurance sector. We find none of the law interaction terms are significant for developed markets. While for the emerging markets, three terms including the rule of law, risk of expropriation and risk of contract repudiation are significant at the 1 per cent level. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of these three law interaction terms on economic growth are 0.61 per cent for RULE, 2.63 per cent for EXPR and 1.68 per cent for CONT. The findings for the life insurance sector suggest the effects of the law environment on the role of life insurance are more significant in emerging markets.

The results of the non-life insurance sector are presented in Table 10. The interaction terms of rule of law efficiency, risk of expropriation and risk of contract repudiation are all positive and statistically significant above the 10 per cent level for developed markets. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of these three law interaction terms on economic growth, respectively, are 0.92 per cent for RULE, 1.95 per cent for EXPR and 1.65 per cent for CONT. For emerging markets, two interaction terms including the risk of expropriation and the risk of contract repudiation are positive and significant at the 5 per cent level. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of these two law interaction terms on economic growth, respectively, are 2.29 per cent for EXPR, and 2.62 per cent for CONT.

In general, the results shown in Tables 8, 9 and 10 are consistent with our expectation that a well-defined legal environment facilitates the functioning of insurance companies, and strengthens the role of insurance in economic growth. Moreover, compared to other law interaction terms, we find that the risk of expropriation and the risk of contract repudiation have a higher impact on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth.

Then we further investigate how governance influences the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. The governance measures adopted in this paper are extracted from Kaufmann et al.,33 and consist of CC, GE, political stability and absence of violence (PV), RQ, rule of law (RL) and VA. We take an average of these measures for each country and include them in the analysis. Tables 11, 12 and 13 present the regression results.

First we find for all insurance sectors, only the political stability interaction term is insignificant in developed markets, while the other five interaction variables are all significant above the 10 per cent level. Specifically, the impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of these five significant governance interaction variables on economic growth, respectively, are 0.46 per cent for CC, 0.58 per cent for GE, 0.70 per cent for RQ, 0.52 per cent for RL and −0.29 per cent for VA. Among others, RQ and GE have relatively higher impacts on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. Moreover, the negative sign of VA is consistent with our expectation, but its impact on the role of insurance is relatively small.

For emerging markets, only two terms including government efficiency and RQ are positive above the 10 per cent significant level, and the other interaction terms are all insignificant. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of the two significant governance interaction variables on economic growth are 0.31 per cent for GE, and 0.28 per cent for RQ. Moreover, the results shown in Table 11 suggest that the impact of governance on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth is more significant in developed markets than in emerging markets.

Table 12 presents the regression results for the life insurance sector. We find the interaction terms of RQ and VA are statistically significant for developed markets. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of the two significant governance interaction variables on economic growth are 0.46 per cent for RQ, and −0.31 per cent for VA. For emerging markets, only the political stability interaction term is positive and significant at the 1 per cent level, and its increase of one standard deviation has an impact of 0.12 per cent on economic growth.

Table 13 presents the regression results for non-life insurance sectors. For developed markets, two interaction terms including GE and rule of law are positive and significant at the 10 per cent level. The impacts of an increase of one standard deviation of the two governance interaction variables on economic growth are 0.36 per cent for GE, and 0.47 per cent for RL. While for emerging markets, only the GE interaction term is positive and significant at the 1 per cent level, and its increase of one standard deviation has an impact of 0.31 per cent on economic growth.

Generally speaking, the results in Tables 11, 12 and 13 suggest that the effect of governance quality on the role of insurance is more significant in developed markets than in emerging markets. Moreover, compared with other governance variables, the government effectiveness and regulatory quality have a relatively higher impact on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth.

Conclusions

In this paper, we propose to use insurance stock returns as an indicator of insurance activities, and apply a dynamic panel technique to investigate the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. Data used in our study consists of information from 38 countries, including 23 developed countries and 15 emerging countries, covering a period between 1982 and 2008. Given that life and non-life insurance could have different impacts on economic growth and the impacts could differ between developed markets and emerging markets, we accordingly divide our sample into nine groups. Our empirical results show that for all nine sample groups after we control for variations of market index returns, there is a significantly positive relationship between the insurance excess returns and future economic growth.

Furthermore, we investigate how country-specific law environment and governance quality affect the link between the role of insurance and economic growth. The empirical results are consistent with our expectation that well-defined law environment and governance quality facilitate the functioning of insurance companies, and strengthen the role of insurance in economic growth. We find generally the effect of law and governance on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth is more significant in developed markets than in emerging markets. Moreover, compared to other law and governance variables, we find that the risk of expropriation and the risk of contract repudiation have a relatively higher impact on the link between the role of insurance and economic growth.

Notes

3 Arena (2008).

7 Fama (1990).

See for example La Porta et al. (1998), Levine (1998, 1999) and Beck et al. (2000) for the effect of law environment, and Svensson (1998) and Chong and Calderón (2000) for the effect of governance quality.

Similar analysis has been conducted using 12 lags of dependent variables as instruments with similar results.

References

Adams, M., Andersson, J., Andersson, L.-F. and Lindmark, M. (2005) The Historical relation between banking, insurance and economic growth in Sweden: 1830 to 1998. Working Paper SBE 2006/2.

Ahn, S. and Schmidt, P. (1995) ‘Efficient estimation of models for dynamic panel data’, Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 5–28.

Arellano, M. and Bond, S. (1991) ‘Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations’, Review of Economic Studies 58 (2): 277–297.

Arellano, M. and Bover, O. (1995) ‘Another look at the instrumental-variable estimation of error-components models’, Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 29–51.

Arena, M. (2008) ‘Does insurance market activity promote economic growth? Country study for industrial and developing countries’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 75 (4): 921–946.

Beck, T., Levine, R. and Loayza, N. (2000) ‘Finance and the sources of growth’, Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1–2): 261–300.

Beenstock, M., Dickinson, G. and Khajuria, S. (1988) ‘The relationship between property-liability insurance premia and income: An international analysis’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 55 (2): 259–272.

Bloom, N., Bond, S. and Reenen, J.V. (2001) The dynamics of investment under uncertainty, IFS Working paper, No. W01/05.

Blundell, R. and Bond, S. (1998) ‘Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models’, Journal of Econometrics 87 (1): 115–143.

Blundell, R., Bond, S. and Windmeijer, F. (2001) ‘Estimation in dynamic panel data models: Improving on the performance of the standard GMM estimator’, in B.H. Baltagi, T.B. Fomby and R.C. Hill (eds.) Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels (Advances in Econometrics, Volume 15), New York, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 53–91.

Browne, M.J., Chung, J. and Frees, E.W. (2000) ‘International property-liability insurance consumption’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 67 (1): 73–90.

Browne, M.J. and Kim, K. (1993) ‘An international analysis of life insurance demand’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 60 (4): 616–634.

Chong, A. and Calderón, C. (2000) ‘Causality and feedback between institutional measures and economic growth’, Economics and Politics 12 (1): 69–81.

Cole, R.A., Moshirian, F. and Wu, Q. (2008) ‘Bank stock returns and economic growth’, Journal of Banking and Finance 32 (6): 995–1007.

Doornik, J., Arellano, M. and Bond, S. (2006) Panel data estimation using DPD for Ox, Working paper.

Esho, N., Kirievsky, A., Ward, D. and Zurbruegg, R. (2004) ‘Law and the determinants of property-casualty insurance’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 71 (2): 265–283.

Fama, E.F. (1990) ‘Stock returns, expected returns, and real activity’, Journal of Finance 45 (4): 1089–1108.

Haiss, P.R. and Sümegi, K. (2007) ‘The relationship of insurance and economic growth? A theoretical and empirical analysis’, Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=968243.

Han, L., Li, D., Moshirian, F. and Tian, Y. (2010) ‘Insurance development and economic growth’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 35 (2): 183–199.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A. and Mastruzzi, M. (2008) ‘Governance matters vii: Aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2007 (June 24)’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4654. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1148386.

Knack, S. and Keefer, P. (1995) ‘Institutions and economic performance: Cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures’, Economic and Politics 7 (3): 207–227.

Kugler, M. and Ofoghi, R. (2005) Does insurance promote economic growth? Evidence from the UK, working paper, Division of Economics, University of Southampton, UK.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1998) ‘Law and finance’, Journal of Political Economy 106 (6): 1115–1155.

La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1999) ‘The quality of government’, The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 15 (1): 222–279.

Levine, R. (1998) ‘The legal environment, banks, and long-run economic growth’, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 30 (3): 596–613.

Levine, R. (1999) ‘Law, finance, and economic growth’, Journal of Financial Intermediation 8 (1–2): 36–67.

Outreville, J.F. (1990) ‘The economic significance of insurance markets in developing countries’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 57 (3): 487–498.

Outreville, J.F. (1996) ‘Life insurance markets in developing countries’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 63 (2): 263–278.

Roodman, D. (2009) ‘How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata’, The Stata Journal 9 (1): 86–136.

Schwert, G.W. (1990) ‘Stock returns and real activity: A century of evidence’, Journal of Finance 45 (4): 1237–1257.

Skipper, H.D. (1998) International Risk and Insurance: An Environmental-Managerial Approach, Boston, McGraw-Hill.

Svensson, J. (1998) ‘Investment, property rights and political instability: Theory and evidence’, European Economic Review 42 (7): 1317–1341.

Ward, D. and Zurbruegg, R. (2000) ‘Does insurance promote economic growth? Evidence from OECD countries’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 67 (4): 489–506.

Webb, I., Grace, M.F. and Skipper, H.D. (2002) The effect of banking and insurance on the growth of capital and output, working paper, Center for Risk Management and Insurance.

Windmeijer, F. (2005) ‘A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators’, Journal of Econometrics 126 (1): 25–51.

Ye, D., Li, D., Chen, Z., Moshirian, F. and Wee, T. (2009) ‘Foreign participation in life insurance markets: Evidence from OECD countries’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 34 (3): 466–482.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 70831004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, C., Wu, C., Li, D. et al. Insurance Stock Returns and Economic Growth. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 37, 405–428 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.22

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.22