Abstract

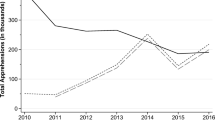

We model illegal immigration across the US-Mexico border into Arizona, California, and Texas as an unobservable variable applying a Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes model. Using state-level data from 1985 to 2004, we test the incentives and deterrents influencing illegal immigration. Better labor market conditions in a US state and worse in Mexico encourage illegal immigration while more intense border enforcement deters it. Estimating the state-specific inflow of illegal Mexican immigrants we find that the 1994/95 peso crisis in Mexico led to significant increases in illegal immigration. US border enforcement policies in the 1990s provided temporary relief while post-9/11 re-enforcement has reduced illegal immigration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our analysis focuses on the inflow of illegal Mexican immigrants into the United States while previous studies also focused on the stock of illegal Mexican immigrants in the US. Throughout the paper we mean the inflow of illegal immigrants when the term illegal immigration to the US is used.

Moreover, Schneider and Enste [2000] provide an excellent overview of MIMIC studies dealing with issues on the shadow economy.

For excellent surveys on this topic see Espenshade [1995], Massey et al. [2002], and Hanson [2006]. Cornelius [2001] comprehensively reviews the efficiency and consequences of the US border policy during the 1990s.

In particular, they find that older Mexicans’ decision to immigrate is driven by US agricultural wages while younger Mexicans’ decision to immigrate is driven by US manufacturing wages. This suggests a change in the composition of illegal immigration by generation: older Mexicans seek agricultural employment in the US, and younger Mexicans more likely seek manufacturing jobs in the US.

See Hanson [2006] for a detailed discussion of the success of illegal immigration enforcement.

Interacting border enforcement with the education level of immigrants attempting to cross the border, Orrenius and Zavodny [2005] find that the deterrent effect is greater the less educated the illegal Mexican immigrants are. This suggests that increasing border enforcement reduces the flow of uneducated illegal Mexican immigrants to the US.

Although the indicators are often only imperfectly linked to the latent variable [Bollen 1989], as explained below, it is reasonable to assume that they at least partly reflect the latent variable — the development of illegal Mexican immigration — and that a change in the incentive to enter the US illegally transmits uniformly to the indicators.

Data for New Mexico are not recorded by the INS.

The overwhelming majority (99 percent) of individuals apprehended at the US-Mexico border by the US Border Control are Mexican citizens [Hanson et al. 2002]. We therefore assume that individuals apprehended at the US-Mexico border are Mexican nationals.

State data are compiled using data for the following US CBP sectors: Tucson and Yuma (Arizona), El Centro and San Diego (California), and Del Rio, El Paso, Laredo, Marfa, and McAllen (Texas).

The assumption of a positive relationship between illegal immigration and linewatch apprehensions is frequently made in the literature [e.g., Espenshade 1994; Hanson and Spilimbergo 1999; Hanson 2006].

US enforcement policies focus on patrolling the border rather than policing non-border counties or monitoring the employment practices of US businesses.

θ is a vector that contains the parameters of the model and Σ(θ) is the covariance matrix as a function of θ implying that each element of the covariance matrix is a function of one or more model parameters.

An alternative is to set the variance of the unobservable variable η to one. However, fixing one element of λ to an a priori value is often more convenient for economic interpretation and thus often applied [Dell’ Anno and Schneider 2009].

Testing stationarity against the alternative of the presence of a unit root using the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin (KPSS) test confirms the results obtained by the ADF test. The results of the unit roots tests are not reported but available upon request. We also tested for cointegration between I(1) indicators and the corresponding determinants but could not confirm any unambiguous cointegration relation.

All calculations have been carried out with LISREL® Version 8.80 using Weighted Least Squares. Tables 1, 2, and 3 show the unstandardized coefficients used in sub-section 4.4 to calculate the state-specific illegal immigration indices. As a robustness check, we also calculate these indices using standardized coefficients. Neither the estimation results nor the calculated indices are sensitive to the choice of coefficients.

According to Hanson et al. [2002], 32 percent of employees working in these industries in California's border regions in 1990 were Mexican immigrants.

For example, Halek and Eisenhauer [2001] find that better educated households are less risk averse. Of course, we cannot measure the degree of risk aversion of the Mexican immigrants studied. However, our empirical results may well be explained by the hypothesis that on average better educated and less risk-averse Mexican immigrants enter the United States at border states with high enforcement levels.

Polgreen and Simpson [2006] find that the labor market quality of newly arriving legal US immigrants improved in the end of the 1990s.

Available upon request.

See Hanson [2006] for a more detailed discussion.

This assumption may be justified given the fact that 57 percent of all undocumented foreign-born individuals in 2002 were Mexican [Passel 2005].

As outlined in the sub-section “Estimation results”,(**Please confirm the change of ‘4.3’ to ‘Estimation results’ ok.) linewatch apprehensions are used as an index variable in order to identify the MIMIC model. The denominator of the index thus equals the number of linewatch apprehensions in the base period. As the latent variable is measured in units of the fixed indicator, illegal immigration is measured in apprehensions of illegal immigrants at the border in the base period.

Since both Passel and Cohn [2008] and Hoefer et al. [2008] estimate the annual inflow of illegal Mexican immigrants to the US to be 330,000, we display only one index.

For details on the INS's Southwest Border Strategy, see General Accounting Office [2001].

References

Bollen, Kenneth A. 1989. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley.

Borjas, George J. 1987. Self-selection and the Earnings of Immigrants. American Economic Review, 77 (4): 531–553.

Borjas, George J. 1995. Assimilation and Changes in Cohort Quality Revisited: What Happened to Immigrant Earnings in the 1980s? Journal of Labor Economics, 13 (2): 201–245.

Borjas, George J., Richard B. Freeman, and Kevin Lang . 1991. Undocumented Mexican-born Workers in the United States: How Many, How Permanent?, in Immigration, Trade, and the Labor Market, edited by John M. Abowd and Richard B. Freeman. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 77–100.

Bratsberg, Bernt 1995. Legal versus Illegal US Immigration and Source Country Characteristics. Southern Economic Journal, 61 (3): 715–727.

Browne, Michael W., and Robert Cudeck . 1993. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. in Testing Structural Equation Models, edited by Bollen, Kenneth A. and Scott Long. Newbury Park: Sage, 136–162.

Buehn, Andreas, and Stefan Eichler . 2009. Smuggling Illegal versus Legal Goods across the US-Mexico Border: A Structural Equations Model Approach. Southern Economic Journal, 76 (2): 328–350.

Chiquiar, Daniel, and Gordon Hanson . 2005. International Migration, Self Selection, and the Distribution of Wages: Evidence from Mexico and the United States. Journal of Political Economy, 113 (2): 239–281.

Cornelius, Wayne A. 2001. Death at the Border: Efficacy and Unintended Consequences of US Immigration Control Policy. Population and Development Review, 27 (4): 661–685.

Costanzo, Joe, Cynthia Davis, Caribert Irazi, Daniel Goodkind, and Roberto Ramirez . 2001. Evaluating Components of International Migration: The Residual Foreign Born Population, US Bureau of the Census Working Paper 61.

Dávila, Alberto, Jose A. Pagán, and Montserrat V. Grau . 1999. Immigration Reform, the INS, and the Distribution of Interior and Border Enforcement Resources. Public Choice, 99 (3–4): 327–345.

Dávila, Alberto, Jose A. Pagán, and Gökce Soydemir . 2002. The Short-term and Long-term Deterrence Effects of INS Border and Interior Enforcement on Undocumented Immigration. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 49 (4): 459–472.

Dell’ Anno, Roberto 2007. The Shadow Economy in Portugal: An Analysis with the MIMIC Approach. Journal of Applied Economics, 10 (2): 253–277.

Dell’ Anno, Roberto, and Friedrich Schneider . 2003. The Shadow Economy of Italy and other OECD Countries: What Do We Know? Journal of Public Finance and Public Choice, 21 (2–3): 97–120.

Dell’ Anno, Roberto, and Friedrich Schneider . 2006. Estimating the Underground Economy: A Response to T. Breusch's Critique. Johannes Kepler University Linz, Department of Economics Working Paper 06/07.

Dell’ Anno, Roberto, and Friedrich Schneider . 2009. A Complex Approach to Estimate the Shadow Economy: The Structural Equation Modelling, in Coping with the Complexity of Economics, edited by M. Faggini and T. Lux. Heidelberg: Springer, 110–130.

Dell’ Anno, Roberto, and Offiong H. Solomon . 2008. Applied Economics, 40 (19): 2537–2255.

Donato, Katharine M., Jorge Durand, and Douglas S. Massey . 1992. Stemming the Tide? Assessing the Deterrent Effects of the Immigration Reform and Control Act. Demography, 29 (2): 139–157.

Espenshade, Thomas J. 1994. Does the Threat of Border Apprehension Deter Undocumented US Immigration. Population and Development Review, 20 (4): 871–892.

Espenshade, Thomas J. 1995. Unauthorized Immigration to the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 21: 195–216.

Farzanegan, Mohammad R. 2009. Illegal Trade in the Iranian Economy: Evidence from a Structural Model. European Journal of Political Economy, 25 (4): 489–507.

Feliciano, Zadia M. 2001. The Skill and Economic Performance of Mexican Immigrants from 1910 to 1990. Explorations in Economic History, 38 (3): 386–409.

Gathmann, Christina 2008. Effects of Enforcement on Illegal Markets: Evidence from Migrant Smuggling along the Southwestern Border. Journal of Public Economics, 92 (10–11): 1926–1941.

General Accounting Office. 2001. INS’ Southwest Border Strategy. Washington, D.C.: United States General Accounting Office.

Halek, Martin, and Joseph G. Eisenhauer . 2001. Demography of Risk Aversion. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 68 (1): 1–24.

Hanson, Gordon H. 2006. Illegal Migration from Mexico to the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 44 (4): 869–924.

Hanson, Gordon H., Raymond Robertson, and Antonio Spilimbergo . 2002. Does Border Enforcement Protect US Workers from Illegal Immigration? Review of Economics and Statistics, 84 (1): 73–92.

Hanson, Gordon H., and Antonio Spilimbergo . 1999. Illegal Immigration, Border Enforcement, and Relative Wages: Evidence from Apprehensions at the US-Mexico Border. American Economic Review, 89 (5): 1337–1357.

Hoefer, Michael, Nancy Rytina, and Bryan C. Baker . 2008. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2007. Washington, D.C.: Office of Immigration Statistics, Policy Directorate, US Department of Homeland Security.

Massey, Douglas S., Jorge Durand, and Nolan J. Malone . 2002. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, Douglas S., and Kristin E. Espinosa . 1997. What's Driving Mexico-US Migration? A Theoretical, Empirical, and Policy Analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 102 (4): 939–999.

McKenzie, David, and Hillel Rapoport . 2007. Network Effects and the Dynamics of Migration and Inequality: Theory and Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 84 (1): 1–24.

Mulaik, Stanley A., Larry R. James, Judith Van Alstine, Nathan Bennett, Sherri Lind, and C. Dean Stilwell . 1989. Evaluation of Goodness-of-fit Indices for Structural Equation Models. Psychological Bulletin, 105 (3): 430–445.

Munshi, Kaivan 2003. Networks in the Modern Economy: Mexican Migrants in the US Labor Market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (2): 549–599.

Orrenius, Pia M. 2001. Illegal Immigration and Enforcement along the US-Mexico Border. Economic and Financial Policy Review, 1 (1): 2–11.

Orrenius, Pia M., and Madeline Zavodny . 2005. Self-selection among Undocumented Immigrants from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 78 (1): 215–240.

Passel, Jeffrey S. 2005. Estimates of the Size and Characteristics of the Undocumented Population. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center Report.

Passel, Jeffrey S. 2006. The Size and Characteristics of the Unauthorized Migrant Population in the US: Estimates Based on the March 2005 Current Population Survey. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center Report.

Passel, Jeffrey S. 2007. Unauthorized Migrants in the United States: Estimates, Methods, and Characteristics, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 57.

Passel, Jeffrey S., and D’Vera Cohn . 2008. Trends in Unauthorized Immigration: Undocumented Inflow Now Trails Legal Inflow. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center Report.

Polgreen, Linnea, and Nicole B. Simpson . 2006. Recent Trends in the Skill Composition of Legal US Immigrants. Southern Economic Journal, 72 (4): 938–957.

Schneider, Friedrich 2005. Shadow Economies Around the World: What Do We Really Know? European Journal of Political Economy, 21 (3): 598–642.

Schneider, Friedrich 2007. Shadow Economies and Corruption All Over the World: New Estimates for 145 Countries. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 2007 (9): 1–66.

Schneider, Friedrich, and Dominik Enste . 2000. Shadow Economies: Size, Causes, and Consequences. The Journal of Economic Literature, 38 (1): 77–114.

Smith, Roger S. 2002. The Underground Economy: Guidance for Policy Makers? Canadian Tax Journal, 50 (5): 1655–1661.

Todaro, Michael P., and Lydia Maruszko . 1987. Illegal Migration and US Immigration Reform: A Conceptual Framework. Population and Development Review, 13 (1): 101–114.

US Immigration and Naturalization Service. 2001. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: 1990–2000. Washington, D.C.: US Immigration and Naturalization Service.

White, Michael J., Frank D. Bean, and Thomas J. Espenshade . 1990. The US 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act and Undocumented Migration to the United States. Population Research and Policy Review, 9 (2): 93–116.

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous referees, the Editor, Joseph P. Daniels, and seminar participants at Technische Universitaet Dresden and Marquette University for many constructive comments that have considerably improved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buehn, A., Eichler, S. Determinants of Illegal Mexican Immigration into the US Southern Border States. Eastern Econ J 39, 464–492 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2012.24

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2012.24