Abstract

The focus of this study is to examine the differential impacts of economic volatility and governance on the flows of US manufacturing and non-manufacturing foreign direct investment (FDI) into African economies. A Generalized Autoregressive Heteroscedastic (GARCH) model is used to generate economic volatility indicators for each sample country. Different governance indices have also been used to test the robustness of the findings. The results of the study show that the influence of economic volatility and governance on aggregate US FDI is weak. For the flows of US manufacturing FDI, effects of economic volatility are undetectable; for this sub-sector, investor confidence, government policy commitment, and availability of labor stand out as major determinants. For US non-manufacturing FDI, however, both economic volatilities and governance have significant effects, although only when economic volatilities occur together with bad governance and high debt burden. Other economic factors, such as trade links between host countries and the US, and between host countries and the rest of the world, also boost the flows of both manufacturing and non-manufacturing US FDI in African economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Even though commonly used statistics on FDI raise conceptual questions, most empirical studies define FDI as an investment that occurs when an investor based in one country (the home country) acquires an asset (10 percent or more of an existing company) in another country (host country) with the intent to manage that asset. Given this definition, FDI comprises three components: new equity from the parent company to the subsidiary, reinvested profits of the subsidiary, and long- and short-term net loans from the parent to the subsidiary.

In the literature, uncertainty is used to encompass all kinds of instability and volatility emanating from economic and political factors. In this study, the term uncertainty refers to both economic and political factors.

In this study, the term political environment refers to the general political situation including instability, uncertainty, and the nature of governance. The variables used in the paper specifically describe the political governance of sample countries.

Also see Robock [1971], Kobrin [1976; 1978], and Desta [1985] for issues to consider when defining political risk in international business.

Li and Resnick [2003] used political indicators from Freedom House and Polity IV databases. The latter data were made available by Marshall and Jaggers [2002].

For a detailed survey of the literature on the determinants of foreign direct investment, see Rayone and Baker [1995].

Itagaki [1981], Abel [1983], and Cushman [1985] also address the effect of uncertainty on capital flows in different settings, such as different sources of input. These studies refer only to economic uncertainty.

Most theoretical studies indicated above empirically test predictions of their respective models in the context of developed countries, mainly the US and UK; for instance see Cushman [1985], Campa [1993], and Goldberg and Kolstad [1995].

For instance, Lehman [1999] used country risk, which is a broader assessment of not only economic but also political risks, and found a significantly negative effect of country risk on the flow of investment from the US to developing countries.

The indicators measure the frequency and nature of sociopolitical events similar to the ones used in tabulating the frequency of occurrence of certain events.

Fosu [2003] established a link between political instability and export performance in the case of SSA economies.

Demand uncertainties (or shocks) are often captured by the volatility in the inflation rate; see Lucas and Prescott [1971].

It is assumed that the firm operates at full capacity so that capacity cost is the same as the cost of production.

To a partial extent at least, foreign investors use capital from a host country in which they invest. Although this assumption seems invalid for the case of African economies, lower cost of capital also signals the presence of domestic investors that provide support to help attract foreign investors.

The US manufacturing sub-sector includes industries dealing with food, chemicals, metals, machinery and equipment, electronics, and transportation.

The US non-manufacturing sub-sector includes industries dealing with wholesale trade, banking, finance, insurance, and other services.

Total FDI from the US is used as a baseline for the purpose of comparing manufacturing and non-manufacturing FDI firms.

For the characteristics of US multinational firms in Africa, see Owhoso et al. [2002].

For the role that colonial ties play, see Bertocchi and Canova [2002].

Questions about the “rule of law” are part of the questionnaire used to construct the composite index. Other sources of political governance and political risk indicators, especially the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG), provide a separate index for “rule of law.” The latter source depends highly on investor response, which may result in a biased assessment of a country's investment and political climate.

See the World Bank publication “Indicators of Governance and Institutional Quality” for comparisons of the alternative indicators. This is available at http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/indicators.htm.

The data set is available for most countries, and the data for some countries extend back to 1,800.

The use of international tourist arrivals as a proxy for new information and confidence for international investors may raise concerns. However, investors get information about a given host country (especially those in Africa) from tourists or visits by the investors themselves. This argument makes particular sense in Africa as investors look for any first-hand information about the political and social system of a given host country since other sources of information about some countries in Africa is not readily available in other media.

For more on the role of government policy, see Teece [1985], Mudambi [1993], Dunning and Narula [1996].

Previous studies have used different methods to generate measures of volatility including lagged prices, unconditional standard deviation, and conditional variance of a variable of interest. For instance, see Carruth et al. [1998] for detailed discussion of the various methodologies to measure uncertainty.

This may also be due to seasonality in the series.

Phillips–Perron is used for the unit root test and the LM test of Engle [1982] is used to test for the presence of ARCH.

The lag length (p) is selected based on the AIC. For both the inflation rate and real exchange rate, the lag length turns out to be 12, which captures information for one year.

In cases where the GARCH (1, 1) model does not fit the series well, ARCH (1) is often adequate.

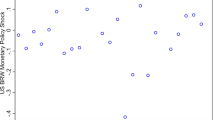

Plots that show the residuals of the inflation rate and the real exchange rate for the sample countries, as well as the conditional variances from GARCH (p, q) estimation, are available from the authors on request.

Studies show that the flow of FDI to African economies is designed to exploit cheap labor and tap into the export sectors, mainly to extract resources [Allaoua and Atkin 1993; Nnadozie 2000; Owhoso et al. 2002]. The trade link variables serve to capture these export sector dimensions.

See Thomas and Worrall [1994] and Baker [1999] for the role of risk and MIGA.

Also see Summary and Summary [1995] for the US case.

See Tomlin [2000] for count data estimation and Chen and Wu [1996] for duration modeling.

For instance, in cases where only one or two firms enter a country, it is possible to know the investment level of each firm if the total value is known. Hence, in order not to reveal this firm-specific information, total values are not reported.

Estimation results for the panel Tobit are not presented here, but are available from the authors on request.

Since economic volatility indicators generated from unconditional variances do not have statistically significant effects on FDI inflow, results are not reported here, but are available from the authors on request.

It may be the case that the direction of causation is not clear. Nevertheless, for the case of trade and FDI between US and African economies, it may be argued that FDI flow is a recent phenomenon preceded by flow of goods and services. Hence, one may argue that trade links are the initial established links that may facilitate the flow of FDI from US into Africa.

The table for these robustness estimates is not reported here to save space, but is available from the authors on request.

Real exchange rate is computed by multiplying the nominal exchange rate of a host country by the ratio of US CPI to host country CPI.

References

Abekah, Joseph Y . 1998. Overseas Private Investment Corporation and Its Effects on U.S. Direct Investment in Africa. Journal of African Finance and Economic Development, 3 (1): 43–64.

Abel, Andrew B . 1983. Optimal Investment Under Uncertainty. American Economic Review, 73 (1): 228–233.

Aizemman, Joshua, and Nancy Marion . 2004. The merits of horizontal versus vertical FDI in the presence of uncertainty. Journal of International Economics, 62: 125–148.

Allaoua, Abdelkader, and Micheal Atkin . 1993. FDI in Africa: Trends, Constraints and Challenges. Ethiopia, Addis Ababa: Economic Commission for Africa (ECA).

Aron, Janine, John Muellbauer, and Benjamin Smit . 2004. A Structural Model of the Inflation Process in South Africa, Center for the Study of African Economies, WPS/2004–08.

Asiedu, Elizabeth . 2002. On the Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment to Developing Countries: Is Africa Different? World Development, 30 (1): 107–119.

Asiedu, Elizabeth . 2004. Policy Reform and Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: Absolute Progress but Relative Decline. Development Policy Review, 22 (1): 41–49.

Asiedu, Elizabeth . 2005. Foreign Direct Investment to Africa: The Role of Natural Resources, Market Policy, Institutions and Political Instability, World Institute for Development Economics Research, Research Paper No. 2005/24.

Baek, In-Mee, and Tamami Okawa . 2001. Foreign Exchange Rates and Japanese Foreign Direct Investment in Asia. Journal of Economics and Business, 53: 69–84.

Baker, C. James . 1999. Foreign Direct Investment in Less Developed Countries: The Role of ICSID and MIGA. USA: Quorum Books.

Basu, Anupam, and Krishna Srinivasan . 2002. Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: Some Case Studies, IMF Working Paper, Working Paper/02/61.

Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan N. Katz . 1995. What to Do (And Not to Do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data. American Political Science, 89 (3): 634–647.

Bennell, Paul . 1995. British Manufacturing Investment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Corporate Responses During Structural Adjustment. The Journal of Development Studies, 32 (2): 195–217.

Bertocchi, Graziella, and Fabio Canova . 2002. Did Colonization Matter for Growth? An Empirical Exploration into the Historical Causes of Africa's Underdevelopment. European Economic Review, 46: 1851–1871.

Blandon, Joseph G . 2001. The Timing of Foreign Direct Investment Under Uncertainty: Evidence from the Spanish Banking Sector. Journal of Economic behavior and organization, 45 (2): 213–224.

Bollerslev, T . 1986. A Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 31: 307–327.

Bollerslev, T., R.Y. Chou, and K.F. Kroner . 1992. ARCH Modeling in Finance: A Review of the Theory and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Econometrics, 52: 5–59.

Campa, Jose’ Manuel . 1993. Entry by Foreign Firms in the United States Under Exchange Rate Uncertainty. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 75 (4): 614–622.

Carruth, Alan, Andy Dickrson, and Andrew Henley . 1998. What Do We Know About Investment Under Uncertainty? UK: Department of Economics, Keynes College, University of Kent.

Chen, Tain-Jy., and Grace Wu . 1996. Determinants of Divestment of FDI in Taiwan. Weltwirtschftliches archiv, 132 (1): 172–184.

Collier, Paul . 1994. The Marginalization of Africa, mimeo, Center for the Study of African Economies.

Crowley, Patrick, and Jim Lee . 2003. Exchange Rate Volatility and Foreign Direct Investment: International Evidence. The International Trade and Journal, XVII (3): 227–252.

Cushman, O. David . 1985. Real Exchange Rate Risk, Expectations, and The level of Direct Investment. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 67 (2): 297–308.

Desta, Asayehgn . 1985. Assessing Political Risk in Less Developed Countries. Journal of Business Strategy, 5 (4): 40–53.

Dixit, Avinash . 1989. Entry and Exit Decision Under Uncertainty. Journal of Political Economy, 97 (3): 620–638.

Dixit, Avinash . 1992. Investment and Hystersis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 6 (1): 107–132.

Dixit, Avinash, and Robert S. Pindyck . 1994. Investment Under Uncertainty. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dunning, John H . 1988. The Eclectic Paradigm of International Production: A Restatement and Some Possible Extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19 (1): 1–31.

Dunning, John H., and Rajneesh Narula . 1996. The Investment Development Path Revisited, in Foreign Direct Investment and Governments: Catalysts for Economic Restructuring, edited by John H. Dunning and Rajneesh Narula. Routledge: Routledge Studies in International Business and the World Economy.

Engle, R.F . 1982. Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity with Estimates of the Variance of United Kingdom Inflation. Econometrica, 50: 987–1007.

Episcopos, Athanasios . 1995. Evidence on the Relationship Between Uncertainty and Irreversible Investment. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 35 (1): 41–52.

Fatehi, K., and M.H. Safizadeh . 1994. The Effect of Sociopolitical Instability on the Flow of Different Types of Foreign Direct Investment. Journal of Business Research, 31: 65–73.

Fosu, Augustin K . 2003. Political Instability and Export Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Development Studies, 39 (4): 68–82.

Freedom House. 2001. Annual Survey of Freedom Country Ratings 1972–73 to 1999–00, Freedom House: Washington, DC.

Goldberg, Linda S., and Charles D. Kolstad . 1995. Foreign Direct Investment, Exchange Rate Variability and Demand Uncertainty. International Economic Review, 36 (4): 855–873.

Grossman, Gene M., and Assaf Razin . 1984. International Capital Movements under Uncertainty. The Journal of Political Economy, 92 (2): 286–306.

Grossman, Gene M., and Assaf Rizan . 1985. Direct Foreign Investment and The Choice of Technique Under Uncertainty. Oxford Economic Papers, 37: 606–620.

Huang, Gene . 1997. Determinants of United States- Japanese Foreign Direct Investment: A Comparison Across Countries and Industries. Garland Publishing: New York and London.

Itagaki, Takao . 1981. The Theory of Multinational Firm Under Exchange Rate Uncertainty. Canadian Journal of Economics, XIV (2): 276–297.

Jeong, Jin-Gil, Philip Fanara, and Charlie E. Mahone . 2002. Intra- and Inter-continental Transmission of Inflation in Africa. Applied Financial Economics, 12 (10): 731–741.

Kobrin, Stephen J . 1976. The Environmental Determinants of Foreign Direct Manufacturing Investment: An Ex Post Empirical Analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 7 (2): 29–42.

Kobrin, Stephen J . 1978. When Does Political Instability Result in Increased Investment Risk? Columbia Journal of World Business, 13 (3): 113–122.

Kobrin, Stephen J . 1979. Political Risk: A Review and Reconsideration. Journal of International Business Studies, 10 (1): 67–80.

Lehman, Alexander . 1999. Country Risks and the Investment Activity of U.S. Multinationals in Developing Countries. IMF Working Paper No. 99/133.

Lemi, Adugna . 2006. Determinants of Sales Destinations of Affiliates of U.S. Multinational Firms in Developing Countries. International Trade Journal, 20 (3): 263–305.

Lemi, Adugna, and Sisay Asefa . 2001. Foreign Direct Investment and Uncertainty: The Case of African Economies, in the Proceedings of the International Business and Economics Research Conference, October 8–12, 2001, Reno, Nevada.

Lensink, Robert . 2002. Is the Uncertainty — Investment Link Non-Linear: Empirical Evidence for Developed Economies. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 138: 131–147.

Li, Quan, and Adam Resnick . 2003. Reversal of Fortunes: Democratic Institutions and Foreign Direct Investment Inflows to Developing Countries. International Organization, 57 (1): 175–211.

Lucas, Robert E . 1990. Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries?. American Economic Review, 80 (2): 92–96.

Lucas, Robert E., and Edward C. Prescott . 1971. Investment Under Uncertainty. Econometrica, 39 (5): 659–681.

Marshall, G.Monty, and Keith Jaggers . 2002. Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2002, Dataset Users’ Manual. Maryland: University of Maryland College Park, College Park.

Morisset, Jacques . 2000. Foreign Direct Investment: Policies also Matter. Transnational Corporations, 9 (2): 107–125.

Moosa, Imad A . 2002. Foreign Direct Investment: Theory, Evidence and Practice. New York, NY, USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mudambi, Ram . 1993. Government Policy toward MNEs in the Presence of Foreign Exchange Scarcity. Eastern Economic Journal, 19 (1): 99–108.

Nnadozie, Emmanuel . 2000. What Determines US Direct Investment in African Countries?, Truman State University Working Paper, Kriksville, MO.

Odedokun, M.O . 1995. An Econometric Explanation of Inflation in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economics, 4 (3): 436–451.

Owhoso, Vincent, Kimberly Gleanson, Ike Mathur, and Charles Malgwi . 2002. Entering the Last Frontier: Expansion by U.S. Multinationals to Africa. International Business Review, 11: 407–430.

Pigato, Miria . 2000. Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: Old tales and New Evidence, Africa Region Working Paper Series, November.

Price, Simon . 1995. Aggregate Uncertainty, Capacity Utilization and Manufacturing Investment. Applied Economics, 27: 147–154.

Rayone, D., and J.C. Baker . 1995. Foreign Direct Investment: A Review and Analysis of the Literature. The International Trade Journal, IX (1): 3–37.

Rivoli, Pietra, and Eugene Salorio . 1996. Foreign direct investment and investment under uncertainty. Journal of International Business Studies, 27 (2): 335–357.

Robock, Steely H . 1971. Political Risk: Identification and Assessment. Columbia Journal of World Business, 6 (4): 6–20.

Rogoff, Kenneth, and Carmen Reinhart . 2003. FDI to Africa: The Role of Price Stability and Currency Instability, IMF Working Paper, wp/03/10.

Senbet, W.Lemma . 1996. Perspective on African Finance and Economic Development. Journal of African Finance and Economic Development, 2 (1): 1–22.

Summary, Rebecca M., and Larry J. Summary . 1995. The Political Economy of United States Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries: An Empirical Analysis. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 34 (3): 80–91.

Sung, Hongmo, and Harvey Lapan . 2000. Strategic Foreign Direct Investment and Exchange Rate Uncertainty. International Economic Review, 41 (2): 411–423.

Teece, David J . 1985. Multinational Enterprise, Internal Governance, and industrial Organization, American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings.

Thomas, Jonathan, and Tim Worrall . 1994. Foreign Direct Investment and the Risk of Expropriation. Review of Economics Studies, 61: 81–108.

Tomlin, Kasaundra M . 2000. The Effects of Model Specification on Foreign Direct Investment Models: An Application of Count Data Models. Southern Economic Journal, 67 (2): 460–468.

UNCTAD. 1998. World Investment Report 1998: Trends and Determinants. New York: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

UNCTAD. 1999. Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: Performance and Potential. New York: UNCTAD.

UNCTAD. 2002. World Investment Report. New York: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Wheeler, David, and Ashoke Mody . 1992. International investment location decisions: The Case of U.S. firms. Journal of International Economics, 33: 57–76.

World Bank. Indicators of Governance and Institutional Quality, available at www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/indicators.htm downloaded May 10, 2005.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Matthew Higgins and Dr Michael Ryan of the Department of Economics, Western Michigan University for their invaluable and constructive comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We also would like to express our appreciation for anonymous referees for their suggestions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

APPENDIX: DATA

APPENDIX: DATA

All the variables used in FDI estimation equations are on an annual basis. The monthly rate of inflation and real exchange rate are used in the ARCH/GARCH model to generate uncertainty indicators and then aggregated to annual frequency in order to be used in the FDI model. The following description lists the variables used in the regression analysis. The main source of data for US FDI is the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) publication “US Direct Investment Abroad: Operations of US Parent Companies and Their Foreign Affiliates” (Table 17, “US Direct Investment Position Abroad on a Historical-Cost Basis”). All other variables except bilateral trade, BIT, membership in multilateral investment guarantee agencies, and political instability are taken from the World Development Indicators and International Financial Statistics of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) CD-ROMs. Data on bilateral trade (export and import) are taken from Direction of Trade Statistics yearbook; BIT and membership in multilateral investment guarantee agencies is compiled from United Nations and World Bank publications [UN, Bilateral Investment Treaties 1959–1999, 2000; World Bank, Convention Establishing the Multinational Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), 2001]. The Freedom House provided the political instability indicator [Freedom House, Annual Survey of Freedom Country Ratings 1972–1973 to 1999–00, 2001].

The following variables are used in the regression:

Dependent variables

- RUSFDI:

-

Ratio of US net FDI in a host country to gross domestic product.

- RUSFDIM:

-

Ratio of US net FDI in manufacturing sectors to gross domestic product.

- RUSFDINM:

-

Ratio of US net FDI in non-manufacturing sectors to GDP.

Economic volatility indicators

- VINF:

-

Conditional variance of inflation generated by GARCH (p, q) model from the monthly inflation rate of host countries and aggregated to annual frequency to relate it to the FDI model.

- VRERFootnote

Real exchange rate is computed by multiplying the nominal exchange rate of a host country by the ratio of US CPI to host country CPI.

: -

Conditional variance of the real exchange rate generated by the GARCH (p, q) model.

Political governance indices

- POLI:

-

Political freedom indicators measured on a one-to-seven scale, with one representing the highest degree of political freedom and seven the lowest (POLI2 is the squared term for POLI).

- DEMOC1:

-

Institutionalization of democracy (DEMOC2 is the squared term for DEMOC).

- AUTOC1:

-

Degree of political competition (AUTOC2 is the squared term for AUTOC).

Investor confidence and government commitment indicators

- REDEBT:

-

Ratio of total external debt of a host country to GDP.

- NINTOU:

-

Ratio of receipts from international tourist arrivals to GDP.

- MIGA:

-

Dummy variable for periods of membership in Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA); equal to 1 for years when a host country signs the agreement and 0 otherwise.

- BIT:

-

Number of bilateral investment treaties signed by a host country with any other countries.

Governance, economic volatility, and debt burden interaction terms

- POLIRERA:

-

Interaction term between the variance of the real exchange rate and the political freedom indicator.

- POLIINFA:

-

Interaction term between the variance of inflation and the political freedom indicator.

- DEBTINF:

-

Interaction term between the variance of inflation and the ratio of external debt to GDP.

- DEBTRER:

-

Interaction term between the variance of inflation and the ratio of external debt to GDP.

Domestic market size, cost of capital, labor and infrastructure

- GDPPC:

-

GDP per capita, which is given by GDP divided by total population of the host country.

- RLR:

-

Real lending rate defined as nominal lending rate minus inflation.

- TELM:

-

Fixed telephone lines per 1,000 people.

- RLFT:

-

Ratio of economically active labor force (aged 15–64) to total population.

- LITRAR:

-

Persons able to read and write as a percent of people ages 15 and above.

Trade link: Size of export sector indicators

- REXPO:

-

Ratio of value of total exports of goods and services to GDP.

- NREXPO:

-

Ratio of total export of a host country (net of export to US) to GDP.

- REXPOTUS:

-

Ratio of total exports to US to GDP.

- RIMPOFUS:

-

Ratio of total imports from US to GDP.

See Tables A1a and A1b.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lemi, A., Asefa, S. Differential Impacts of Economic Volatility and Governance on Manufacturing and Non-Manufacturing Foreign Direct Investments: The Case of US Multinationals in Africa. Eastern Econ J 35, 367–395 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2008.17

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2008.17