Abstract

Accounts of changes over time in the focus of direct marketing need not necessarily be subjective. Analysis of the frequency with which words appear in the Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice makes it possible to identify marketing concepts that have gained or lost traction during the past 12 years. Many indicative keywords can be consolidated into keyword groups, sets of associated terms, and thereby used to identify changes over time in the thematic focus of contributions to the Journal. Numerical changes in the frequency of use of words within these keyword groups make it possible to quantify changes over time in the ‘footprint’ of different thematic areas of interest to marketers. From such analysis, there is strong evidence not just of the growth of coverage of topics relating to social media but also the decline in the coverage of CRM and, perhaps more surprisingly, of the business and organizational context within which the practice of direct marketing has historically been undertaken.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The keynote paper in this Journal's anniversary issue chronicles the evolution of the direct marketing industry during the 150 or so years since its introduction as a business model in America. The account is necessarily both personal and subjective. In a profession that accords such importance to evidence, how can we be sure that our perception of trends is accurate? Is there any way we can adduce information about the nature of change in the direct marketing profession so as to validate or correct personal impressions?

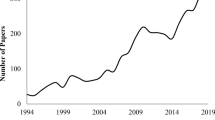

One source of such information, the authors felt, would be analysis of the contents of the Journal itself. Text mining is a generic term used to describe the analysis of content. One of its most celebrated uses has been to inform the dispute about who it was who authored the plays we historically credit to William Shakespeare. It is widely used in business to monitor customer satisfaction through an examination of the balance of positive and negative sentiments in customer communications. Market researchers use it to analyse the content of focus groups. It is text analysis that underpins the identification of words that are currently ‘trending’. Indeed, the detailed parsing and interpretation of text string frequencies is arguably the core competence that has contributed most to Google's meteoric rise.

Despite these applications, this is, so far as we are aware, the first occasion on which text mining has been used to track the changing focus of a profession, such as direct and digital marketing, through the analysis of journal content.

Data

The findings of this paper are based on the examination of a file containing the entire content of the Journal of Direct, Database and Digital Marketing Practice between Volume 1, which was published in July 1999, and Volume 13, published in April 2012. This content includes not just featured papers but also abstracts, book reviews, technology and legal updates, references and indeed any other text material printed in each issue.

It was our intention to measure changes in content over as long a period as possible while maintaining a sufficiently large body of content to ensure that statistical comparisons were not unduly affected by the particular topic covered by any one paper. We therefore decided to compare the contents of journal issues published during a three and a half-year period starting July 1999 with the contents of issues published between July 2008 and April 2012. The following analyses are based on a comparison between the contents of what we refer to as the ‘earlier’ issues and those of the ‘later’ issues.

Between them the contributors to the earlier issues and the later issues wrote 1.45 million separate ‘words’. These include not just dictionary words but also acronyms, such as ‘CRM’, proper nouns, such as ‘Tesco’, and abbreviations, such as ‘vol.’. To make their arguments, contributors to the Journal found it necessary to use 33,000 different words. ‘Amazingly’ and ‘Amazoned’ are two of over 13,000 different words that were used only once by a contributor to the Journal during these periods.

To search for insight among this content, we decided to remove from the 1.45 million words all instances of a text string or word with fewer than a hundred occurrences during either the earlier or the later issues. Those with a hundred or more occurrences during either period were then examined individually in order to decide whether or not the word had particular relevance to the field of direct marketing in its widest sense. Words not retained for further analysis include words such as ‘but’, ‘two’ or ‘being’ whose variation in frequency is more dependent on the stylistic preferences of the author than the subject matter of his or her paper.

Finally, we identified and removed from further analysis text strings whose frequency, and more particularly changes in frequency, was unduly affected by editorial decisions. The words ‘research’ and ‘originality’ are examples of such text strings because they form part of the template by which abstracts are evaluated.

Note that each of the remaining text strings represents a single word or acronym. Thus, the term ‘CRM’ will be included, so too will ‘customer’, ‘relationship’ and ‘management’ but not ‘customer relationship management’ as a complex term. We recognize that this is a weakness, but did not have access to software that could provide this level of textual analysis.

A total of 263 text strings managed to pass this series of filters. This paper refers to these as ‘keywords’. That does not mean that these words are actually used by journal papers as keywords for the purposes of searching by readers, although many will have been. By keywords we mean words that are of critical importance in enabling contributors to write about the concepts, processes and practice of direct marketing.

These keywords were themselves split into two categories according to whether they appeared more frequently in the earlier issues or in the later ones. In total, there were 162,000 different instances of the use of one of these keywords during the earlier and later issues. Divide the total number of words — 1.45 million — by that number and it is evident that approximately every ninth word in the Journal's content was one of these keywords.

Readers will be reassured to learn that the most common keyword is ‘marketing’, appearing once in every 150 words, followed by ‘customer’, once in every 217 and ‘customers’, once in every 234. These are followed by ‘business’, ‘research’ and ‘information’. The least commonly used keywords, in other words the ones that were used barely a hundred times in one of the two periods, were ‘blogs’, ‘synergy’ and ‘usability’.

Measuring changes in the ‘footprint’ of the Journal over time

In order to track shifts in the subject matter of the Journal, we rank the 263 keywords according to the absolute change in the frequency of their use between the earlier and later issues of the Journal.

There are 104 keywords that were more commonly used towards the end of the period than at the beginning. Proportionately, their use increased from 18 per cent to 33 per cent of all the keywords in a journal issue, an increase of over 80 per cent. The highest percentage, rather than absolute increases, was for the words ‘Facebook’ and ‘blogs’, words for which, not surprisingly, not a single entry was recorded during the earlier issues of the Journal. Given changes in the use of the internet, it will be no surprise that the largest absolute growth of usage was in the keywords ‘social’, ‘media’, ‘campaign’ and ‘mobile’.

By grouping the 104 emerging keywords on a thematic basis, we were able to identify six evolutionary developments in marketing practice whose coverage in the Journal has achieved the greatest growth in terms of keyword usage. For example, the keywords ‘social’ and ‘media’ are the two most common terms in a group of fast-growing keywords, which include terms relating to the internet within which, for the sake of convenience, we have also included ‘Google’, ‘search’ and ‘engines. ‘Facebook’, ‘blogs’, ‘community’ and ‘communities’, ‘mobile’, ‘networks’, ‘links’ and ‘reach’ also belong in this group. The facets of marketing practice that this group of keywords refers to are too obvious to need further explanation.

Table 1 examines these six keywords groups in terms of the number of times they were used in the Journal and how this has changed over time. Each row represents a different keyword group. It is described using the two or more most commonly used keywords in that group. Thus, the keywords ‘social’, ‘media’ and ‘search’ are the most frequently used words in the first keyword group (referenced as group A in Table 1).

From the column showing the number of keywords in each group, we can see that the group relating to ‘campaigns’ and ‘results’ had the largest number of keywords that had increased over the period. From the next two columns, we can see that in aggregate the use of these words increased from 6,871 to 10,163, an increase (shown in the next column) of 3,292 or (shown in the next column) 47.9 per cent. Although this keyword group constituted a similar overall increase in content to that of social media and search, in percentage terms the growth of coverage of social media and search had been very much more rapid, having started from a smaller base.

Given that the absolute increase in the use of the 104 upward trending keywords over this period was 11,662, the growth in use of keywords relating to ‘campaigns’ and ‘results’ (3,292) represented 28.2 per cent of the total increase in upwardly trending keywords (the figure shown in the final column).

It occurred to us that this information could be used to measure what we describe as the footprint of different key topics in the Journal and to understand how this footprint had changed over time. By footprint we mean the percentage of the Journal's content given over to a particular set of related topics.

Taking the topic of social media and search, for example, we can see from Table 2 that in the earlier issues the 15 keywords relating to this topic represented 2.20 per cent of keyword occurrences. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that the footprint of this topic in earlier issues was 2.20 per cent. In the later editions, this percentage had grown to 8.28 per cent. In other words, the space allocated to this topic had increased by 6.08 per cent of the Journal's total coverage. This figure is clearly a more reliable way of tracking the growth of coverage of the topic than simply counting the growth in the number of papers with social media or search as their subject.

If we add up the increase in the footprint of the six topics (or keyword groups) that grew over this period, this represents 12 per cent of the total content of the Journal. This level of change suggests that, however important the effect on direct marketing of the internet and the resulting new companies and techniques it made possible, there has been a gradual evolution rather than an abrupt transformation in the overall content of the Journal.

Within any keyword group, inevitably the use of some keywords has grown faster than that of others. From Table 3, which lists the keywords in the social media and search keyword group, it is evident that while the coverage given to ‘social’ and ‘media’ has grown by a similar amount, it has been from a different sized base reflecting that the term ‘media’ had many other uses before its use within the concept of ‘social media’.

Accounting for changes in keyword usage

Not quite as large in terms of absolute increase as words relating to social media, but nonetheless accounting for more than a quarter of additional footprint over the period, is a set of keywords relating to brand marketing. This group is led by keywords such as ‘campaign’, ‘results’ and ‘brand’ and incorporates consumer-oriented concepts such as ‘quality’, ‘engagement’, ‘attitude’ and ‘exposure’. This keyword group was already much better established than the ‘social’/’media’ keyword group and still has a larger footprint. However, in absolute terms the growth has been smaller.

We were surprised how rapidly so many of these keywords had grown. There is nothing particularly modern about the concepts these keywords represent — it is just that these issues do seem to be written about more often by contributors from which we assume that they are a topic of growing interest to practitioners.

Table 1 showed that there are four other keyword groups that have increased their footprint, a group relating to ‘analytics’ and ‘segmentation’, one relating to ‘students’ and ‘teaching’, one relating to ‘governance’ and ‘compliance’ and one relating to ‘on-line’ and ‘multichannel’. These other keyword groups are perhaps better interpreted in the context of the decline of the keyword groups some of them appear to be replacing (Table 4).

For example, evidence suggest that, whereas marketers are currently much concerned with the issues of ‘governance’, ‘compliance’, ‘risk’ and ‘security’, this appears to be at the expense of reduced interest in the keyword group including ‘permission’, ‘protection’ (as in data protection), ‘privacy’ and ‘fraud’. In other words, satisfying regulatory bodies seems to be overtaking keeping on-side with the consumer as a source of marketing concern. Does this reflect a trend away from the customer-centric culture advocated in the late 1990s?

While ‘financial performance’ remains a major topic, the appearance of words associated with it has substantially fallen. This may seem strange in an era when marketing has been under increased pressure to demonstrate its financial contribution to the business.

Similarly, keywords in earlier issues that related to ‘knowledge’ through the use of ‘measurement’ resulting in ‘models’ used for ‘targeting’ have ceded ground to a new set of keywords involving broadly similar concepts, but using different terminology. Thus, ‘knowledge’ has been displaced by the use of the term ‘insight’, ‘models’ by ‘techniques’ and ‘methods’, and ‘targeting’ by ‘segmentation’.

This group of keywords is joined by terms such as ‘automated’, ‘automation’ and ‘tracking’. To some extent, this shift in keywords reflects a change in semantics; however, we would argue that it also represents a shift in business priorities, from the construction of tools for more effective targeting of new prospects to the maximization of response from existing customers, and from enquirers through the use of segmentation based on automated or semi-automated tools for the rapid development of models for optimizing customer communications.

The growth of the cluster of keywords relating to ‘students’ and ‘teaching’ probably derives less from a shift in the marketing environment as from either an increased effectiveness on the part of the Institute of Direct and Digital Marketing (IDM) in using its educational activities to source content for the Journal, or more focus in the Journal on the core activity of the IDM. To the extent that the growth of any one keyword group is precipitated by another's decline, attention should be drawn to the declining coverage of matters relating to the keywords ‘donor’, charity’ and ‘fundraising’.

The biggest drop in footprint over this period is the space given to keywords associated with the concepts of ‘system(s)’, ‘customer(s)’, ‘relationship(s)’ and ‘management’. This theme accounts for more than a quarter of the total loss of footprint.

‘Customer’, ‘customers’ and ‘CRM’ themselves are the biggest losers, joined by ‘technology/ies’, ‘processes’ and ‘loyalty’, all key elements that justified investment in CRM. Big declines are also evident in the keywords relating to ‘computer(s)’, ‘programmes’, ‘databases’ and ‘infrastructure’ — possibly reflecting the ubiquity of technology within marketing and business in general — as well as the related consumer-facing concepts of ‘transactions’, ‘customizations’, ‘individual’ and ‘dialogue’. This decline takes with it considerations relating to ‘response’, ‘revenue’ and ‘competition/competitive’, and the attainment of ‘integrated’, ‘corporate’, and ‘objectives’.

One possible reason for the declining footprint of CRM is that it has now become an established and well-understood business approach supported by well-developed technical infrastructure. Alternatively, it may represent a failure to extend its influence beyond a limited set of large-scale marketing organizations. More likely, the focus on CRM has been disrupted by the emergence of social media, which is perceived as a more cost-efficient method of understanding and engaging with customers.

The shift into the digital world has resulted in two other clusters of declining keywords. During this period, there has been a fall of 70 per cent in the number of references to the ‘internet’. Other fading terms are the keywords ‘web’ and ‘websites’ and those beginning with ‘E-‘, particularly ‘e-commerce’, ‘e-business’ and ‘e-marketing’ as well to a lesser degree as ‘e-mail’. This decline is primarily associated with changes in the terminology we use to describe processes, not in the processes themselves. Similarly, it seems that few contributors any longer make use of words such as ‘one-to-one’, ‘interactive’/’interactivity’ or ‘electronic’. These concepts are all commonly understood and taken into account. Another smaller declining keyword group includes the now rather dated terms such as ‘video’, ‘paper’ and ‘channel’ as well as the concept ‘communication(s)’ itself.

These losses of footprint are relatively small in relation to a key area whose fall could reasonably be considered a very serious issue both for the industry and the Journal itself, namely, the decline of direct marketing as a business model on which a distinctive business could be developed, as, for instance, in the time of Sears Roebuck or Reader's Digest (see companion paper on pp. 291–309). Our former Editor, a distinguished pioneer and practitioner of direct marketing, is one of a generation of direct marketing specialists who considered themselves primarily as business managers or consultants in contrast to many contemporary specialists. It would be disappointing if in future it will no longer be possible to combine these two competencies in a single career — the contents of this declining keyword group suggest that this represents a serious risk to the profession.

The keyword group headed by the terms ‘business’ and ‘information’ is very large, containing 38 keywords. Many of these keywords describe the process of business and financial management such as ‘financial’, ‘performance’, ‘companies’, ‘management’ and ‘managers’, ‘strategies’, ‘selling’, ‘retailers’ and ’consumers’. ‘Costs’, ‘approach’, ‘distribution’, ‘suppliers’ and ‘chain’ reveal the declining coverage given by the Journal to the physical distribution of goods.

Conclusions

This particular exercise in word frequency analysis may be of interest either as an example of how textual analysis can be used to generate insights and/or substantively, as a record of the changing focus of the direct marketing industry.

Once text files have been supplied in a form in which they can be interpreted, the analysis involved in generating results is relatively straightforward and quick to complete. In this case, Excel was sufficient for the processing and analysis of the 1.4 million words of the Journal. The results are simple enough for all to understand.

The process of selecting appropriate keywords from the list of different text strings contained in the Journal, ensuring that they are relevant to a particular industry, is one that has to be undertaken manually. However, the process could be made more rigorous, were it possible to access information on the comparative frequency of words in other academic or trade journals.

Care needs to be taken to avoid including words whose frequency distribution is affected by editorial policy, especially if the text one works from constitutes the entirety of the printed publication, not just the content of published papers. For example, the replacement of the word ‘organisation’ with ‘organization’ in this analysis merely reflects a change in spelling policy resulting from a change of publisher.

On the basis of this study, measuring the absolute change in word usage appears to be a more useful measure than proportionate change. A side benefit of the use of absolute change is that it then becomes possible to measure the total extent of the footprint change resulting from the change in keyword frequencies.

The organization of keywords into thematic keyword groups is a somewhat arbitrary process, not least because there is no way of unambiguously delineating boundaries between keyword groups. In this particular case, this process could have been undertaken with greater objectivity had it been possible to retain information showing which combinations of keywords co-appear in the same published papers.

Clearly, it is impossible to know with certainty how far shifts in keyword frequencies represent editorial decisions, conscious or unintended. That must ultimately be a matter for interpretation by the organization concerned, in this case the IDM. In our judgement, the majority of the footprint change is exogenous to the Journal, that is, a reflection of changes in the real world as interpreted by those who contribute their view of that world to the Journal.

Some of the keyword clusters described in this paper do represent changes in the terms we used to describe the same thing. This occurred to a much lesser extent than we had anticipated and, even where it is the case, it is usually possible to see that it is for reasons other than a change in fashion. Thus, targeting and segmentation, although often used as synonyms, do have subtle differences in meaning and it is not difficult to understand why the use of the latter should have grown at the expense of the former.

The analysis also demonstrates how frequently new meanings can attach to common words, particularly those associated with new technology such as ‘social’, ‘community’, ‘network’ and ‘mobile’.

While most changes in keyword frequency originate as a result of technological innovation, there are important and substantial footprint changes that are better explained in terms of evolutions in business and organizational priorities. Examples of this are the declining prominence given to direct marketing as a business strategy and the involvement of its professionals in decisions regarding the optimization of return on investment through the maximization of long-term customer value.

What can word frequency analysis tell us that we do not already know? To answer this question, we took the precaution of inviting the Editorial Board to nominate the ten keywords that they thought would have increased by most and the ten that they thought would have decreased the most over the time period of the analysis.

While this expert group were all successful in identifying the increases in footprint associated with ‘social’ ‘media’ and ‘search’, none of them had unprompted awareness of the growth of the footprint of keywords relating to ‘brands’ incorporating keywords such as ‘quality’, ‘attitudes’ and ‘engagement’.

Similarly, while the group identified that coverage of ‘CRM’, ‘systems’ and ‘technology’ had declined, it was surprised at the extent of the decline in coverage given to the keyword group relating to ‘business’, ‘information’ and ‘financial’ ‘performance’.

In summary, it proves easier to identify emerging trends than to identify the topics whose footprint they displace and easier to identify new trends that grow from a low base than the continuing increase in the coverage of topics which are already well established.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Webber, R., Stroud, D. How changes in word frequencies reveal changes in the focus of the JDDDMP. J Direct Data Digit Mark Pract 14, 310–320 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2013.19

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2013.19