Abstract

This article examines the tension between efficiency and customer experience management in retailing. It concludes that one way forward is to give customers the tools to manage their own experience. To put it another way, in these industries, it is up to the customer to manage their own experience. In some industries, such as complex financial services, regulatory barriers prevent self-service, on the grounds that advisors know better than consumers what the latter need. However, these barriers will eventually collapse as consumers use improved information technology, including advising each other via social media, to identify products that they want, at the right price. Where customer service is concerned, suppliers will increase their focus on efficiency and margin, and seek the win-win of self-fulfilled customer experience with minimised human intervention from staff. Consumers will be provided with ever more sophisticated information and communications technology, particularly but not solely by suppliers who use a multi-channel approach. Younger consumers’ strong preferences for buying in their own way will eventually pervade most markets. Suppliers who fail to come to terms with this will lose market share to those who lead in applying information and communications technology to support self-service. Eventually, the self-fulfilled experience will be the norm, except in most difficult and risky purchases. Even here the role of human intervention will be minimised. Consumers will increasingly use their own technology, especially smart-phones, to identify the best offers, make comparisons between products and services, and receive offers from national and local suppliers. For more complex products and services or buying situations, expert third party diagnosis of customer needs will be replaced by self-diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

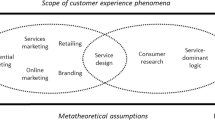

CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE – DEFINITION AND DETERMINANTS

Customer experience has attracted the attention of management writers – academic and professional – as well as that of suppliers of systems and consultancy aimed at enhancing customers’ experiences. There has been a lack of clarity about the meaning of the term. It is sometimes referred to as something that suppliers manage directly as opposed to the view taken in this article, which is that it is the customer's response – personal, rational, emotional or even spiritual – to contacts with a company. Experience is created not just by things retailers control (for example, service interface, retail atmosphere, assortment, price), but also by things outside their control (for example, influence of others, purpose of shopping). Customer experience includes the total experience, including search, purchase, consumption and after-sale phases of the experience. It may involve multiple retail channels.1

Customer experience does not take place in a vacuum. A key determinant is expectations, created by, among other factors, consumers’ previous experience, word of mouth, branding and other communication they might have received about the retailer (or its competitors). On-line and off-line experiences interact, so expectations about one may be determined by experience of the other. Anticipation involves information processing, exploration, reminiscing, self-justification and seeking affirmation. These elements are often emotional – satisfying the desire to feel good, excited, guilt-free or accepted rather than just being rational decision steps. They play a strong part in influencing the purchasing decision.2

WHAT CONSUMERS WANT

It is easy to make sweeping generalisations about consumer needs – whether one is arguing for or against focusing on the customer experience. The situation is complicated, but there are clear trends. Most consumers are attracted by the core offer – product range, location, layout and so on. Of course, shoppers with different objectives, for example, recreational shoppers, may have different needs.3 Further, channel proliferation creates new challenges for retailers, who must understand how consumers differ in how they search for information and buy in different channels.

Many consumers seem to think that retailers offer poor service, and claim to be intolerant of bad service. However, there is little evidence that consumers switch between retailers when they experience bad service, though they may abandon individual visits for specific service reasons. Many surveys mention poor service by retailers.4 For example, ORC International, announced in January 2011 research findings that showed that half of UK consumers are likely to encounter poor customer service in an average month. The worst culprit for poor service was the retail sector, with 17 per cent of respondents unimpressed with their experiences. Closely following were broadband suppliers and banks, with 16 and 15 per cent, respectively. If those who were unsatisfied switched, we would see much more switching than we do! Surveys that focus particularly on retailing identify that customers frequently leave stores because they cannot find merchandise and rely on (often) unobliging staff to tell them where to find it, unavailable merchandise or queue lengths. For example, according to the Retail Eyes September 2010 report, 92 per cent confirmed they had left an establishment before making a purchase after receiving poor customer service, which is 36 per cent higher than Retail Eyes’ 2009 survey. When a shopper asks where to find a product, 76 per cent expect to be taken to its location and not just pointed in the general direction. Ninety-seven per cent admit to using self-service checkouts, though 66 per cent of these people still prefer to use tills with staff for the interaction and half of the 5712 respondents said that when they are paying they prefer to have a conversation other than that specific to the transaction. Still, the business case for giving staff ‘time to talk’ is weak, given self-service economics.

With these and similar researches, one must be very careful when it comes to interpretation. My interpretation is that the economic model of solving the service problem by more staff and more staff training and motivation does not stack up.

One interesting piece of research identified three segments – multi-channel enthusiasts, uninvolved shoppers and store-focused consumers. Psychographic and demographic customer characteristics (for example, price consciousness, time pressure) produce different perceptions of the costs and benefits of multi-channel search and purchase strategies, which in turn determine how consumers like to search for information and then buy. Multi-channel enthusiasts tend to be more innovative, whereas store-focused consumers generally are more loyal than multi-channel enthusiasts. However, multi-channel consumers have higher purchase volumes though are less likely to be loyal to brands or retailers. However, multi-channel enthusiasts consider shopping a more pleasurable experience than the other two segments, whereas uninvolved shoppers do not consider shopping pleasurable at all. The multi-channel enthusiast segment is small in the clothing category but accounts for a majority of consumers in the electronics category.5

Where on-line shopping is concerned, satisfaction and trust are important. These influence each other, and in turn are determined by fulfilment/reliability, website design, security/privacy and customer service. Off-line performance affects perceptions of on-line performance. Consumers base their purchase decisions not only on online retailers’ website appearance and functionality, but on evaluations of the entire service offer, including offline performance. A well-designed user interface reduces customers’ search costs and time required for information processing, leading to greater satisfaction.6 Multi-channel customers have higher expectations of the customer experience, particularly the on-line aspect. Personal recommendation is very important, particularly for on-line sites.

Consumers are generally very focused on the core retail offer – are the products available, across the range, at the right price? Experience issues are important, but for most consumers are dominated by the core retail offer issues. One reason for this may be that consumers who are most obsessive about service may have already migrated much of their business to the web. Most consumers treat experience issues as hygiene factors, not factors that determine their choice of retailer. It takes quite bad service to deter customers.

DO CONSUMERS’ NEEDS VARY BY TYPE OF STORE/SHOPPING OBJECTIVE?

Retailing covers a wide range of product and service types, and it is realistic to expect consumer behaviour to vary according to the type of store they are visiting and their shopping objectives. Physical (that is, store/outlet-based) retailing splits into several categories. They range from pure self-service to situations where advice, explanation, order-taking and possibly actual service delivery (for example, restaurants, coffee, home installation) is required. At the other extreme is retailing that is entirely contact centre- and/or web-based, while some physical retailing requires the support of either or both of these channels. Home delivery and after-sales service (itself ranging from regular servicing/preventive maintenance to repair servicing) add important extra dimensions. The extent of personal contact varies from nil (or nearly nil if you include delivery of physical products) in the case of web-based purchasing to intense in the case of buying a product that involves a lot of diagnosis and advice.

The benefits sought by consumers from low-touch and high-touch retailers vary significantly, and consumers evaluate the role of ICT in supporting transactions and experience differently, according to the nature of the transaction. For simple products, for example, grocery, consumers just want systems that simplify and speed transactions. For more complex products, involving diagnosis, delivery and service, customers want systems that enable them to configure products and customise service.7

Figure 1 gives examples of where some retail operations sit on the high tech, high touch spectrum. I expect most retail businesses will migrate towards the top left cell.

Pervasive information systems, which include ways for consumers to visualise products, are valued by customers. They affect several dimensions of the shopping experience, namely entertainment, shopping efficiency, budget monitoring, time pressure, information search, checkout problems and promotions overload.8

HOW RETAILERS ARE RESPONDING

Retailers realise than store and on-line experience are seen by consumers as related, and are investing to ensure that one or the other does not let them down. The best retailers – those that survive, grow and increase their profits relative to the rest of their industry tend to have a strong vision related to how they present themselves to a particular segment. They are very clear about their offering, the identity of their target segment, and their value proposition. This core offering is usually very strongly focused on merchandise range, price and layout, and sometimes on store size and location. Customer service is rarely a differentiator. Where they introduce new retailing concepts, it is the core offer that changes. The core offer is increasingly focused on emotional as well as functional benefits, but these often relate to personal control over the shopping situation.

The best retailers evolve their offering. Retailing is an industry built for tests and experiments. With different locations – and now websites – concepts can be modified and refreshed, until they are ready for roll-out to achieve economies of scale. We can therefore expect increasing experimentation with self-service (self-diagnosis, self-selection and self-fulfilment).

Many big physical retailers have withdrawn wherever possible from using the human factor in managing the customer experience, reserving it (decreasingly) for check-outs and for queries, and shelf-filling. These retailers are not too concerned about the customer experience, considering that their overall proposition (for example, brand, location, layout, merchandise range, pricing) does most of the job of attracting and retaining customers and maximising their spend. For these retailers, information and communications technology focuses on increasing the efficiency of processing customers.

Retailers with strong service have traditionally focused on the human element in the customer experience. They too are learning how to manage this more effectively, with better research tools and information and communications technology helping them to identify how much traffic they are generating and what level of service they are providing. A strong focus on training and motivation ensures that what these techniques cannot help consumers deliver to themselves is delivered by staff.

For many retailers, the customer experience focus has moved to multi-channel operations, ensuring that websites and contact centres deliver an experience that encourages customers to get what they want, and return time and again. With the customer being remote, customer experience is more important. If it is negative, the customer may just put the telephone down or leave the site – very different from when the customer is already in the store, perhaps having parked, filled a basket, or spent time considering or even trying a product. However, in e-channels, a separate customer experience focus may not be visible, as customer experience management is an integral part of managing channels.

So, where web and contact centre are not important channels, a retailer's customer experience focus may seem low. However, where they are important channels, before, during or after the sale, customer experience is important. Where customer experience is poorly managed in such channels, it is visible in poor integration and communication.

One exception to the above is the booming interest in in-store technologies – displays, in-store Internet access, virtual reality for trying on apparel, and the like. Here, the issue of customer experience is still to the fore. These are mostly tools for helping customers deliver to themselves, allowing staff to focus on managing throughput in various ways. Another exception is location-based marketing, using smart-phone-based couponing or other incentives. This is proving a promising way of getting customers into a store.

Where does this leave the older technologies of customer contact, such as mail order? In early 2011, J C Penney announced closure of its catalogue operations to reduce ‘investment in areas of the business that no longer contribute meaningfully to its financial performance’. Catalogues are now more often used for branding and as a route to the web –they initiate sales but rarely close them. Catalogues stimulate customers to go to websites to browse and order. Eventually, however, catalogues may all be flippable e-catalogues for e-book readers and laptops.

Figure 2 suggests the journey of most store-based retailers. They start with the essentials, followed by experimentation, partly driven by the technologies that are available, before finalising their customer self-fulfilled format – though few are in the latter situation.

Implications for systems and networks

Even though we can divide retailing into low and how touch, and shoppers into multi-channel devotees and store shoppers, there is no doubt that both will see a dramatic increase in the use of information technology to enhance the customer experience. This information technology will be integrated, and dependent on communication networks, the quality of which will therefore be critical. The conventional low touch retailers (for example, grocery) will have to invest in digital signage, radio frequency identification devices, information provision, self-service and a wide variety of other information systems simply because it makes shopping fun and faster. The high-touch retailers will do it because it involves customers even more deeply, allowing them to visualise, explore and fantasise. Consumers will use social media to find and recommend the best performers, and retailers will respond to their views, harnessing instead of resisting their content. Online and offline reputations will be managed integrally by retailers, and failure in one because of poor IT and networks will be resisted strongly because of the damage likely to be done to the other. Concepts such as mobile couponing, which drive customers from on-line to off-line, will increasingly be seen as the key to off-line success. More basic concepts, such as kiosks and self-check-out, will rapidly become hygiene factors.

Conclusions

It is easy for smart management consultants to tell the directors of IT, Marketing, Customer Service and IT that they are spoiling the customer experience. The retailers’ own data tells them that even if they are imperfect, customers keep coming in and buying, profitably too. Generally, when retailers go out of business, it is due to failures in their core retailing model or an ill-advised strategy. The same was true of CRM – poor CRM does not kill, good CRM adds profit.

Store location, merchandise range, store layout, pricing, branding and logistics remain at the centre of retailers’ concerns. Customer experience is a hygiene factor, but its quality can be improved by smart use of information and telecommunications systems (which are critical for most core retail elements). The store of the future will be wired/wireless. Wiring for customer experience will be a way of keeping customers happy and often a side effect of decisions taken to improve store efficiency. Customer expectations as to what will be in the basic hygiene level of store IT will rise. The sexy customer-facing applications (virtual reality and so on) will not necessarily be a differentiator, may occasionally attract customers, and may not even keep them loyal, but they will help customers who are already in the store buy or buy more.

In on-line retailing, the battle lines have already been drawn. The sites that involve customers most and generate trust by the comprehensiveness and quality of their offer and the security of delivery on-time, undamaged and so on will keep ahead.

References and Notes

Morschett, D., Swoboda, B. and Schramm-Klein, H. (2006) Competitive strategies in retailing – an investigation of the applicability of Porter's framework for food retailers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 13 (4): 275–287.

Turnbull, J. (2010) Anticipated Consumption: Leading the Customer Experience. Sydney: Macquarie Graduate School of Management, Macquarie University.

Bäckström, K. and Johansson, U. (2006) Creating and consuming experiences in retail store environments: Comparing retailer and consumer perspectives. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 13 (6): 417–430.

Many of these surveys show conflicting results. Thus, the e-Gain early 2010 research claimed that the North American retail sector ranked first overall in customer service. Overall performance for the sector increased significantly from a score of 1.8, or below average, out of 4.0 in 2009 to 2.3, which is above average, in 2010, highest among all sectors evaluated. Cross-channel customer experience, while still slightly ‘below average’, was still the highest among all sectors included in the research. Meanwhile, the latest 2011 ACSI data Customer satisfaction with supermarkets slipped for the first time in 3 years, falling 1.3 per cent to an ACSI score of 75. Higher food prices were a major contributor – overall cost of food rose 1.5 per cent in 2010 after declining in 2009, and some major food items increased much more. This suggests that satisfaction is more closely related to the core offer.

Konus, U., Verhoef, P.C. and Neslin, S.A. (2008) Multichannel shopper segments and their covariates. Journal of Retailing 84 (4): 398–413.

Kim, J., Jin, B. and Swinney, J.L. (2009) The role of retail quality, e-satisfaction and e-trust in online loyalty development process. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 16 (4): 239–247.

Gil-Saura, I., Berenguer-Contrí, G. and Ruiz-Molina, M.-E. (2009) Information and communication technology in retailing: A cross-industry comparison. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 16 (3): 232–238.

Ayanso, A., Lertwachara, K. and Thongpapanl, N. (2010) Technology-enabled retail services and online sales performance. Journal of Computer Information Systems 50 (3): 102–111.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stone, M. The death of personal service: Why retailers make consumers responsible for their own customer experience. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 18, 233–239 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2011.29

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2011.29