Abstract

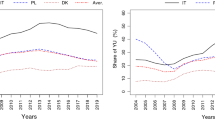

This paper assesses the impact of the recent crisis on the NEET (neither in employment or education or training) rate and the youth unemployment rate in EU regions. We use Eurostat data for the 2000–2010 period and focus on changes in both indices from 2000–2008 to 2009–2010. Employing Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) and bias-corrected Least Squares Dummy Variables (LSDV) dynamic panel data estimators, implemented by pooling both all regions and different groups of countries, we find that NEET rates are persistent and that persistence increases over the crisis period but that results vary depending on which of five regional groups is considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Notice that NEET is not computed for the labor force. Thus, the different denominator (compared to UR) explains the lower values compared with the unemployment rate. However, the numerator includes not only the unemployed but also young people who are not in education or training.

International institutions have also recognized the importance of the NEET indicator, which was initially adopted to study problems of young workers in the United Kingdom. The initiative, ‘Youth on the Move’, part of the Europe 2020 program (European Commission, 2010), emphasizes the importance of focusing on the NEET rate.

Bulgaria, Ireland, Italy and Spain have very high NEET rates (above 17%); high rates are also found in the United Kingdom; average rates are found in France, Portugal and some Eastern European countries; low rates are found in Germany, Sweden and Finland; the lowest rates (less than 7%) are found in the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

See Arpaia and Curci (2010), who produced a broad analysis of labor market adjustments in the EU-27 after the 2008–2009 recession in terms of employment, unemployment, hours worked and wages.

According to the ILO (2012), if the unemployment rate is adjusted for drop-outs induced by the economic crisis, the global YUR in 2011 would rise from 12.6% to 13.6%.

For a recent review of the main determinants (macroeconomic, demographic, structural, institutional, etc), see Marelli et al. (2013).

To provide a flavor: taxes on labor, unemployment benefits (in terms of amount, duration and replacement ratio), degree of unionization (union density and union coverage), collective bargaining (degree of coordination and/or centralization), minimum wages, employment protection legislation (EPL), incidence of temporary or part-time contracts, active labor market policies and, in the case of young people, educational systems and school-to-work transitions.

For a recent exception, see Marelli et al. (2012).

In this way, we have GDP (computed) data through 2010, while the regional data for gross value added in real terms are available only through 2009.

In this estimation framework, the time dimension spans from 2001 through 2010, as only the first time observation, 2000, is sacrificed to the dynamics.

A further complication is that the bias approximations of xtlsdvc do not support interactions involving the lagged dependent variable. Entirely new bias approximations would be necessary in this case.

We are grateful to a referee of this journal for suggesting such extension.

Observe that some Eastern European countries with many regions, such as Poland, were only mildly affected by the Great Recession.

Time lags, more remote than the first, of the dependent variable spatial lag yield valid instruments in the absence of serial correlation and are used in Baltagi et al. (2014). We decided not to include them to minimize problems associated with instrument proliferation.

References

Arellano, M and Bond, S . 1991: Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies 58 (2): 277–297.

Arpaia, A and Curci, N . 2010: EU labour market behaviour during the great recession. European Economy Economic Papers 405, European Commission, Brussels.

Baltagi, BH, Fingleton, B and Pirotte, A . 2014: Estimating and forecasting with a dynamic spatial panel data model. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 76 (1): 112–138.

Blanchard, OJ and Katz, LF . 1992: Regional evolutions. Brooking Papers on Economic Activities 23 (1): 1–75.

Blundell, R and Bond, S . 1998: Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87 (1): 115–143.

Bruno, GSF . 2005a: Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Economics Letters 87 (3): 361–366.

Bruno, GSF . 2005b: Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel data models with a small number of individuals. The Stata Journal 5 (4): 473–500.

Bruno, GSF, Choudhry, M, Marelli, E and Signorelli, M . 2014: The short- and long-run impacts of financial crises on youth unemployment in OECD countries. Presented at the SIE Congress, Trento, 23–25 October.

Caroleo, F.E. and Pastore, F . 2007: The youth experience gap: Explaining differences across EU countries. Quaderni del Dipartimento di Economia, Finanza e Statistica 41, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy.

Choudhry, M, Marelli, E and Signorelli, M . 2012: Youth unemployment rate and impact of financial crises. International Journal of Manpower 33 (1): 76–95.

Drukker, DM, Egger, P and Prucha, IR . 2013: On two step estimation of a spatial autoregressive model with autoregressive disturbances and endogenous regressors. Econometrics Reviews 32 (5–6): 686–733.

Elhorst, JP . 2003: The mystery of regional unemployment differentials: Theoretical and empirical explanations. Journal of Economic Surveys 17 (5): 709–748.

Esping-Andersen, G . 1990: The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press: Cambridge.

Eurofound. 2012: NEETs – Young people not in employment, education or training: Characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg.

European Commission. 2010: Youth on the move. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg.

ILO. 2012: Global employment trends for youth 2012. ILO: Geneva.

IMF. 2010: World economic outlook: Rebalancing growth. IMF: Washington.

Kiviet, JF . 1995: On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 53–78.

Marelli, E, Choudhry, MT and Signorelli, M . 2013: Youth and the total unemployment rate: The impact of policies and institutions. Rivista internazionale di scienze sociali 121 (1): 63–86.

Marelli, E, Patuelli, R and Signorelli, M . 2012: Regional unemployment in the EU before and after the global crisis. Post-communist Economies 24 (2): 155–175.

OECD. 2006: Employment outlook. OECD: Paris.

O’Higgins, N . 2011: The impact of the economic and financial crisis and the policy response on youth employment in the European Union. Presented at the Eaces International Workshop, Perugia, 10–11 November.

O’Higgins, N . 2012: This time it’s different? Youth labor markets during the ‘great recession’. Comparative Economic Studies 54 (2): 395–412.

Roodman, D . 2009: A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 71 (1): 135–158.

Scarpetta, S, Sonnet, A and Manfredi, T . 2010: Rising youth unemployment during the crisis: How to prevent negative long-term consequences on a generation? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 6, Paris.

Windmeijer, F . 2005: A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics 126 (1): 25–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bruno, G., Marelli, E. & Signorelli, M. The Rise of NEET and Youth Unemployment in EU Regions after the Crisis. Comp Econ Stud 56, 592–615 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.27

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.27