Abstract

Do transition economies carry features distinct from those of mature economies? Exploring the relation between debt and inflation in mature and transition economies in a two-sector model with endogenous industrial structure, structural factors are shown to hinder achieving balanced performance on debt and inflation for transition economies, quite distinct from mature economies. The Maastricht criteria on debt and inflation, making no distinction between these types of economies, serve as a frame of reference. Should both types of economies face the same euro-zone entry conditions? As our reasoning shows how one size does not fit all, our answer is no.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For description and context as well as critique of the Maastricht criteria on debt and inflation, see for example Buiter (2005), Buti and Giudice (2007), Gros (2003, 1995).

For the original renditions of what we now call the Balassa-Samuelson model, see Balassa (1964) and Samuelson (1964). And for the Baumol-Bowen effect, see Baumol and Bowen (1965).

This is, admittedly, a somewhat extreme assumption made for mathematical simplicity. A more realistic assumption of significantly smaller sectoral productivity growth differential for mature market economies, relative to transition economies, empirically supported by, for example, Mihaljek (2002), would introduce significant mathematical complications without bringing new insights. Given that the model's results are of qualitative rather than quantitative nature, such a simplifying assumption does not appear unwarranted, particularly as in this paper the concept of mature economy mostly just serves the purpose of helping to define a transition economy. The main findings of the current paper concern transition economies and sub-groups of transition economies, with mature economies serving as a contrasting background. Moving from a comparison between mature and transition to observations strictly within the genre of transition economies, the question arises whether substantial productivity growth differentials are exclusively a feature of early-stage transition economies – that would not be considered candidates for EU membership. Jazbec (2002) demonstrates that this is not so. The author shows the evolution of productivity in industry (tradables) and services (nontradables) in Slovenia for the period 1993–2001; see Figure 2 of that paper. Slovenia is an example of an advanced transition economy, which in the meantime has not only become a member of the EU but also a member of the euro collaboration. The paper shows that from 1993 to 1995 productivity grew at roughly equal rate in both sectors. However, beginning in 1996 productivity growth in services stagnated, while productivity in industry grew substantially and steadily up to the ending year of the data series, 2001, steadily increasing the gap between productivity in the two sectors. By 2001, Slovenia was well under way with its preparation to join the European Union, with EU membership occurring in 2004. This Slovenian example shows that it is not only the early-stage transition economies that are characterized by large sectoral productivity growth differentials, but that this phenomenon can also be found among rather advanced transition economies. More recently, Bah and Brada (2009), using a three-sector model, agriculture, industry and services, and using total factor productivity, TFP, demonstrate that this gap in productivity growth between tradable and nontradable sector (industry and services) persists for transition economies into the years after EU membership. Their data series runs from 1995 to 2005. This is shown to be the case for Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria, where the latter did not attain EU membership during the period of investigation. Interestingly, their results show that for a number of transition countries the steepest productivity growth occurred in agriculture. This is demonstrated for Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia. Since the authors’ model does not account for agricultural trade, it invites speculation that if we augment the tradable sector by including agricultural trade the productivity growth difference between tradable and nontradable sectors would be even larger. Mas (2010) provides further empirical support for our modeling assumptions. On the basis of the EUKLEM 2009 data, the analysis brings forth three main points regarding productivity: (1) The tradable sector's (manufacturing sector) contribution to labor productivity is significantly stronger for the EU-10, the 10 new EU member states that joined in 2004, predominantly consisting of transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe, compared with the old EU member states; (2) across the board for all countries analyzed the tradable sector's (manufacturing) contribution to labor productivity growth exceeds that of the nontradable sector; and (3) the difference in productivity growth between the two sectors is substantially larger in the new EU-10 compared with the old EU member states.

In a small open economy, both international inflation, that is, world market prices, and the rate of devaluation are completely passed on to domestic inflation. This is the case, even though the price index comprises both nontradable and tradable goods, each scaled down by their share of aggregate production. The reason for the complete pass-through is that, according to the Scandinavian Model of Inflation, wage growth is determined in the tradable sector and carried over into the nontradable sector. The extreme pass-through to domestic inflation in this theory finds empirical support by Velickovski and Pugh (2011). In a meta-regression analysis of exchange rate pass-through covering 23 mature market economies and 12 transition economies, the authors report the following findings with regard to differences between transition and mature market economies: There are no statistically significant differences in the magnitude of exchange rate pass-through to import prices. However, exchange rate pass-through to consumer prices is ‘significantly and substantially higher’ in transition economies than in mature economies. The authors conjecture that this latter finding reflects high levels of openness, which is in congruence with SMI's assumption of a small open economy.

This relation between price increases in the tradable and nontradable sector finds empirical support in the literature. For example, De Gregorio et al. (1993) confirm this for a sample of 14 OECD countries for the time period 1970–1985. The data show that inflation over the indicated time interval was predominantly driven by price increases in the nontradable sector.

For an elaboration on the relation between subsidies and economic growth, see Borgersen and King (2012).

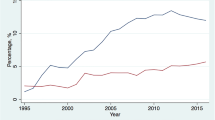

Using quarterly EuroStat data from 1995 to 2005, Kočenda et al. (2008) show that in terms of debt-to-GDP ratio the 10, mostly East European, countries that joined the European Union in 2004 outperformed the old EU members in the early part of the above time interval, by having lower debt-to-GDP ratios, with Hungary being an exception. However, from 2001 onward debt-to-GDP ratios of the group of 10 increased noticeably. In addition, the differences in the debt-to-GDP performance between individual transition economies increase.

For an elaboration on how expressions 3 and 4 are derived, see Borgersen and King (2011a).

The (0, 1) domain and range of f is in accordance with Definitions 1 and 3.

See Borgersen and King (2011b) for comparative statics.

When simplifying the relation between relative sector sizes and the productivity growth differential as in expression 12, we find (1−α)=1−(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b, measuring how much a 1% change in the productivity growth differential changes the tradable sector's share of value added.

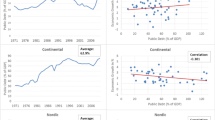

Empirical support for a shift toward a greater share of the nontradable sector during transition is provided by, for example, Landesmann (2000). Using econometric analysis of the patterns of structural change in Central and East European transition countries over a decade (1989–1999) – that is, before EU accession of the first group of transition countries – Landesmann finds evidence of a relative decline in the share of the industrial sector (tradables) and a relative increase in the share of the service sector (nontradables). This is documented by both the evolution of employment structures, (see Figure 1.1 in Landesmann (2000)), and the evolution of value-added structures (Figure 1.2 in the quoted reference). More recently, Bah and Brada (2009), examining the time interval 1995–2005, show that this trend continues for transition economies beyond their date of entry into the European Union (2004). Havlik (2007) analyzes the 10 new EU member states of 2004, as well as Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine, as well as aggregates of the new EU members who joined the EU in 2004, and the group of 15 old EU members over the time period 1990–2003. The author documents a clear shift from manufacturing (tradables) to services (nontradables), both in terms of gross value added and in terms of employment structures.

In both a speedy newcomer and an advanced and dynamic transition economy, the increase in the subsidizing sector, α, accompanying an increase in the productivity growth differential, exceeds the existing subsidizing ratio. This reduces the value of the latter, and thereby also the subsidizing burden of each unit of production in the subsidizing sector. This allows a larger proportion of the productivity growth differential to be used for improving the allocation of resources. Economies characterized by this relation are able to change their structural composition faster and keep pace in the transition process. When the relation between the change in the relative size of the subsiding sector and the subsidizing ratio is the opposite, the transition process is difficult to get going in a slow starter, or eventually loses momentum in an advanced and stagnant transition economy. As the industrial structure varies along the transition trajectory, so does the critical value of the sector size elasticity necessary to keep the transition process on track.

This follows from (13) and (16).

This follows from (14) and (17).

By Definition 1 we have α defined on the open interval (0, 1). Endpoint values would mean that we lose the two-sector structure of the economy, and, for α=0 would introduce division by zero into the ratios describing the industrial structure.

It should be noted that Definition 1 constrains α∈(0, 1) so that the endpoints are excluded.

This is given by (10).

In the context of this model position on the transition trajectory is defined in terms of sectoral composition of the economy, with a dominant tradable sector indicating an early stage and a dominant non-tradable sector indicating an advanced stage on the transition trajectory.

References

Bah, E and Brada, J . 2009: Total factor productivity growth, structural change and convergence in the new members of the European Union. Comparative Economic Studies 51 (4): 421–436.

Balassa, B . 1964: The purchasing power parity doctrine: A reappraisal. Journal of Political Economy 72 (6): 584–596.

Baumol, WJ and Bowen, WG . 1965: On the performing arts: The anatomy of their economic problems. American Economic Review 50 (2): 495–502.

Blanchard, O . 1997: The economics of post-communist transition. Clarendon Lectures in Economics. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Borgersen, TA and King, RM . 2011a: When Balassa-Samuelson comes to Maastricht: Debt-sustainability, growth and transition. Arbeidsrapport (Working-Paper) 2011–3, Østfold University College.

Borgersen, TA and King, RM . 2011b: Inflation in Latvia: How real is it? Eastern European Economics 49 (3): 26–53.

Borgersen, TA and King, RM . 2011c: Reallocation and restructuring: A generalization of the Balassa-Samuelson effect. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 22 (4): 287–298.

Borgersen, TA and King, RM . 2012: Export-led growth in transition economies: The role of industrial structure, productivity growth differentials and cross-sectoral subsidies. Social Science Research Network (SSRN) Working Paper 2178313, 20 November, http://ssrn.com/abstract=2178313.

Buiter, WH. 2005: The sense and nonsense of Maastricht revisited: What have we learned about stabilization in EMU. Journal of Common Market Studies 44 (4): 687–710.

Buti, M and Giudice, G . 2007: Maastricht's fiscal rules at ten: An assessment. Chapter three, In: Paganetto, L (ed). The Political Economy of the European Constitution, Chapter 3. Ashgate Publishing Limited: Burlington, Hampshire, UK, pp. 23–47.

De Gregorio, J, Giovanni, A and Wolf, HC . 1993: International evidence on tradables and non-tradables inflation. NBER Working Paper # 4438, August, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Domar, ED . 1944: The ‘burden of debt’ and the national income. American Economic Review 34 (4): 798–827.

Égert, B, Lommatzsch, IDK and Rault, C . 2003: The Balassa-Samuelson effect in Central and Eastern Europe: Myth or reality? Journal of Comparative Economics 31 (3): 552–572.

Gros, D . 1995: Excessive debts and deficits. Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) Working Document No. 97, October, Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels.

Gros, D . 2003: A stability pact for public debt? Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) Brief, No. 30, January, Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels.

Havlik, P . 2007: Economic restructuring in the new EU member states and selected newly independent states: Effects of growth, employment and productivity. Proceedings of OeNB Worskops No. 12, 5 and 6th of March: Emerging markets: Any lessons for Southeastern Europe, Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Central Bank of Austria): Vienna, pp. 10–47.

Jazbec, B . 2002: Balassa-Samuelson effect in transition economies: The case of Slovenia. William Davidson Working Paper Number 507, October, The William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan Business School.

Kočenda, E, Kutan, AM and Yigit, TM . 2008: Fiscal convergence in the European Union. North American Journal of Economics and Finance 19 (3): 319–330.

Landesmann, M . 2000: Structural change in the transition economies 1989 to 1999. In: Economic Survey of Europe 2000 No. 2/3, Chapter 4. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE): Geneva, pp. 95–121.

Lindbeck, A . (ed) 1979: Imported and structural inflation and aggregate demand: The Scandinavian model reconstructed. In: Inflation and Employment in Open Economies. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Mas, M . 2010: ICT and productivity growth in advanced economies. ICTNET Assessment paper, OECD ICTNET, 25 November, http://community.oecd.org/docs/DOC-18558.

Mihaljek, D . 2002: The Balassa-Samuelson effect in central Europe: A disaggregated analysis. Paper presented at the conference ‘Exchange rate strategies during the EU enlargement’, Budapest, 27–30 November.

Samuelson, PA . 1964: Theoretical notes on trade problems. The Review of Economics and Statistics XL. VI (2): 111–154.

Velickovski, I and Pugh, GT . 2011: Constraints on exchange rate flexibility in transition economies: A meta-regression analysis of exchange rate pass-through. Applied Economics 43 (27): 4111–4125.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the 4th International Conference ‘Economic Challenges in Enlarged Europe’ held on 17–19 June 2012 at the Tallinn School of Economics and Business Administration, Tallinn Technical University, Estonia, as well as the participants of the CEUS Conference 2012, ‘Challenges to Stability in the Euro Area’, held at WHU-Otto Beisheim School of Management, Vallendar, Germany on 24–25 May 2012, and the participants of the 7th Annual International Conference on Public Policy and Management, ‘Societies in Transition’ arranged by the Center for Public Policy at the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore, India, on 16-18 August 2012 for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Special thanks go to two anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A

In this appendix, we reproduce the proofs for expressions (16) and (17) given by Borgersen and King (2011a).

Conditions (16) and (17) are, respectively,

When sector sizes are allowed to change, the sustainable debt-to-GDP ratio in a transition economy can be expressed as

From (A.1) we derive conditions under which the sustainable debt-to-GDP ratio increases and/or decreases in sectoral productivity growth differential, that is, conditions under which

is positively (respectively negatively) valued.

For the sign of this expression the sign of the numerator −a[(b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b−1] is decisive.

−a[(b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b−1]<0 if (b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b>1. By the definition of α the last inequality is expressed as (b+1)α>1, or, equivalently b>((1−α)/α).

Analogously −a[(b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b−1]>0 if (b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b<1, or equivalently if b<((1−α)/α).

Finally, (for the purpose of completion) −a[(b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b−1]=0 if (b+1)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b=1, equivalently if b=((1−α)/α). □

APPENDIX B

(a) To show that for an advanced and dynamic transition economy the relation b>((1−α)/α) holds:

By (12a) b>((1−α)/α) is equivalent to (α′/α)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )>((1−α)/α)>1, where the last inequality is given by Table 1 as a defining feature of an advanced transition economy.

Thus, (α′/α)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )>1. Substituting for α′ from (12c) we obtain (b(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b−1/α)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )>1, which simplifies to (b(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b/α)>1. Upon substitution from (12b) this gives (bα/α)>1, which simplifies to the condition b>1, which we know to be true for the case of advanced and dynamic transition economies by Table 1.

(b) To show that for a slow starter the relation b<((1−α)/α) holds:

By (12a) b<((1−α)/α) is equivalent to (α′/α)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )<((1−α)/α)<1, where the last inequality is given by Table 1 as a defining feature of a slow starter.

Thus, (α′/α)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )<1. Substituting for α′ from (12c) we obtain (b(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b−1/α)(q̇ T −q̇ NT )<1, which simplifies to (b(q̇ T −q̇ NT )b/α)<1. Upon substitution from (12b) this gives (bα/α)<1 which simplifies to the condition b<1, which we know to be true for the case of a slow starter by Table 1. □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borgersen, TA., King, R. Relating Debt to Inflation among Transition Economies: A Blueprint from Mature Economies?. Comp Econ Stud 55, 606–635 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2013.11

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2013.11