Abstract

This paper reviews labour market policy options to accelerate the return to work after the Great Recession. To do so, it first examines the change over time in the degree of vulnerability to unemployment persistence by looking at the impact of policy determinants on the flows in and out of unemployment. It then considers the prospects for a rebound in the unemployment outflow rate by reviewing evidence regarding matching efficiency and duration dependence. Finally, based on the empirical evidence provided, it assesses the possible contribution of a range of policies to enrich the job content of a post-crisis recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A related risk is persistent unemployment eventually leads to falling labour force participation rates due to discouragement effects.

In both Spain and the United States, productivity growth over the period exceeded trend estimates. Even though hourly productivity gains have been frequently observed during previous recessions in the United States – though not during the 1982 and 1991 recessions – the extent of the increase in 2008–2009 has been surprisingly strong. These gains are likely to hide significant composition effects since job losses were largely concentrated in low-productivity sectors such as construction (OECD, 2009).

Another factor, not directly addressed in this paper, is the possibility that the crisis may have led to an increase in the structural unemployment rate through a rise in the cost of capital due to higher risk premia.

In the long run, an important property of the wage and price-setting framework is that the level of compensation (including payroll taxes) that firms can afford to pay – referred to as the feasible or warranted wage – is essentially determined by trend productivity and the cost of capital, and is, therefore, independent from the level of employment or unemployment (Blanchard and Katz, 1999; Blanchard, 2000).

On the empirical side, the wage-setting price-setting framework has sparked a lot of research on the potential role of labour and product market institutions (Nickell, 1990, 1998; Layard et al., 1991; Elmeskov and MacFarlan, 1993; Elmeskov et al., 1998; OECD, 1994, 2006; Blanchard and Wolfers, 2000; Bassanini and Duval, 2006, 2009; Fiori et al., 2007).

The weaker influence of long-term unemployed on wage setting may be due to a number of factors associated with duration dependence effects such as the loss of human capital (Pissarides, 1990), a reduction in the intensity and effectiveness of job search, some form of discrimination by employers based on spells duration (Blanchard and Diamond, 1994) and shifts in social norms towards higher tolerance vis-à-vis the status of long-term unemployment (Lindbeck, 1995).

As argued in several studies (Shimer, 2007; Elsby et al., 2008), this simplifying assumption has a modest influence on the calculation of flows, especially for the outflow rate. For instance, Rogerson and Shimer (2010) report almost identical unemployment–employment or employment–unemployment transition probabilities stemming from either a two-states or a three-states model (adding inactivity) for the United States.

The countries included in the flow regressions are Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States.

The interaction between the proxy of benefits duration and the initial replacement rate, which is equal to the average replacement rate, was never found to be a significant determinant of either the log unemployment rate or log unemployment flow variables in the empirical specifications explored for this paper. Hence, it has been excluded from the analysis.

Direct job creation includes temporary work, and in some cases, regular jobs in the public sector or in non-profit organisations, offered to unemployed persons. As for training, it is measured as including both publicly funded training programmes for the unemployed (and workers at risk of losing jobs), as well as grants to enterprises for more general staff training.

The series is smoothed using the HP filter with a smoothness parameter set at a high enough value to ensure that only the low-frequency correlations are picked-up in the regression. There is still a possibility of remaining endogeneity bias, insofar as policymakers may in the longer run raise spending per person unemployed in response to higher unemployment. However, given that the endogenous response would in such case lead to a positive correlation between spending and unemployment, the finding of a negative coefficient would suggest that this bias is not too strong.

The OECD indicators of EPL for temporary contracts are unable to account for such differences in enforcement. For instance, regulations in France and Spain are recorded as being similar although enforcement in Spain is weaker (see, for instance, Bentolila et al., 2010). Controlling for the actual share of temporary contracts is one way to account for such differences.

This measures also captures changes in terms of trade, whose influence on the wedge is, however, empirically irrelevant for most of the countries and periods considered.

Both the minimum wage (as a percent of median wage) and excess coverage are measured as country-specific averages over time.

Comparing the extent with which differences in pre-crisis labour market settings across countries may have made countries more or less prone to unemployment persistence is a more difficult exercise since it would require assessing how the existing mix of policies affects this risk in the aftermath of an adverse demand shock, taking into account both policy interactions and the pursuit of other policy objectives (eg, distributional ones).

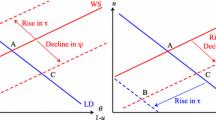

In the wage-setting/price-setting framework, persistence allows for the introduction of a short-term equilibrium rate of unemployment (NAIRU), that is distinct from the long-run equilibrium or structural rate. In this context, NAIRU estimates can be interpreted as providing information on the degree of unemployment persistence.

Inflow and outflow rates are defined, respectively, as the probabilities that an employed worker becomes unemployed within the following month and that an unemployed worker exits unemployment within the same time span. Under this methodology the ‘steady-state’ level of unemployment can be approximated by the (log-) difference between the inflow and outflow rates.

In fact, the estimates also suggest, somewhat unexpectedly, that spending on PES lowers the inflow rate for prime-age men and women resulting in an ambiguous aggregate effect on turnover.

The absence of evidence of a stronger negative correlation between the stringency of employment protection legislation and unemployment flows is surprising but could reflect the lack of variation in the policy variable over time in the sample.

The effect on turnover could be mostly related to the on-the-job part of such spending, which firms can use as a tool for ‘experimenting’ workers skills. One general limitation of these empirical analyses is that they do not account for differences in the quality of training programmes across countries.

While there is no previous evidence to draw on, the estimates reported here suggest that spending on direct job creation has contradictory effects on the level and turnover of unemployment for certain categories of workers. For instance, such spending appears to lower both turnover and unemployment of youth and, to a lesser extent, women by reducing inflows more strongly than outflows.

Most of the existing studies focus on micro data and test the effect of different kinds of training policies on employment outcomes of participants at different time horizons. See, for instance, Friedlander and Burtless (1996), Dyke et al. (2006) and Hotz and Scholz (2000) for the United States, and Gerfin and Lechner (2002) for Europe.

To some extent, this conclusion is corroborated by the results from earlier studies, which have also found stringent product market regulation and high unemployment benefits to be associated with stronger hysteresis effects (Furceri and Mourougane, 2009; Guichard and Rusticelli, 2010).

The measured outflow rates shown in Figure 7 do not distinguish between exits into jobs and withdrawals from the labour force.

In part this is due to the lack of sufficiently long and reliable time series on vacancies and outflow rates.

That is, the outflow rate is significantly lower than what would be expected taking into account labour market tightness prevailing at that time, suggesting a breakdown of the relationship, which can be interpreted as a decline in matching efficiency.

One limitation of the methodology and data used in Elsby et al. (2008) is that no control is made for the influence of the composition of the unemployment pool on observed negative duration dependence. Individuals with different characteristics such as age, gender or education level will generally enter an unemployment spell with different probabilities of exit, which is independent from the spell duration. Therefore, it is possible that findings of duration dependence effects reflect a growing share of workers with intrinsically low exit rates in the unemployment pool as average duration increases, rather than a gradual decline over time in the probability of exit faced by individuals due to skill erosion or other hysteresis effects.

See in particular Bover et al. (2002) and Garcia-Perez et al. (2010) in the case of Spain. Earlier studies reviewed in Machin and Manning (1999) generally found little evidence of positive duration dependence in the case of several European countries.

For instance, empirical analysis has found that the outflow rate tends to fall at the time when the unemployed are in receipt of benefits (Bover et al., 2002).

The authors use an elasticity derived from earlier studies, which estimated the impact of a change in US benefit duration on the length of unemployment spells over time, while controlling for the potential endogeneity bias (Katz and Meyer, 1990; Card and Levine, 2000).

References

Aaronson, D, Mazumder, B and Schechter, S . 2010: What is behind the rise in long-term unemployment? Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago 2Q (2010): 28–51.

Andrews, D, Caldera Sanchez, A and Johansson, A . 2011: Housing markets and structural policies in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Paper no. 836.

Arnold, J, Brys, B, Heady, C, Johansson, A, Schwellnus, C and Vartia, L . 2011: Tax policy for economic recovery and growth. Economic Journal 121 (550): 59–80.

Bassanini, A and Duval, R . 2006: Employment patterns in OECD countries: Reassessing the role of policies and institutions. OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 486, OECD, Paris.

Bassanini, A and Duval, R . 2009: Unemployment, institutions and reform complementarities: Re-assessing the aggregate evidence for OECD countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25 (1): 40–59.

Bassanini, A, Garnero, A, Marianna, P and Martin, S . 2010: Institutional determinants of worker flows: A cross-country/cross-industry approach. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers no. 107, OECD: Paris.

Bentolila, S, Cahuc, P, Dolado, JJ and Le Barbanchon, T . 2010: Two-tier labor markets in the great recession: France vs. Spain. CEPR Discussion Papers 8152.

Blanchard, O . 2000: The economics of unemployment. Shocks, institutions and interactions. Lionel Robbins Lectures, London School of Economics, October.

Blanchard, O and Diamond, P . 1994: Ranking, unemployment duration and wages. Review of Economic Studies 61 (3): 417–434.

Blanchard, O and Katz, L . 1999: Wage dynamics: Reconciling theory and evidence. The American Economic Review 89 (2): 69–74.

Blanchard, O and Wolfers, J . 2000: The role of shocks and institutions in the rise of European unemployment: The aggregate evidence. NBER Working Paper no. 7282.

Boeri, T and Garibaldi, P . 2009: Beyond eurosclerosis. Economic Policy 24 (59): 409–460.

Boone, J and van Ours, JC . 2009: Why is there a spike in the job finding rate at benefit exhaustion? CEPR Discussion Papers no. 7525.

Bover, O, Arellano, M and Bentolila, S . 2002: Unemployment duration, benefit duration and the business cycle. The Economic Journal 112 (April): 223–265.

Cahuc, P and Postel-Vinay, F . 2002: Temporary jobs, employment protection and labor market performance. Labour Economics 9 (1): 63–91.

Calmfors, L and Driffill, J . 1988: Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance. Economic Policy 3 (6): 16–61.

Cameron, C and Trivedi, P . 2005: Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press: New York.

Card, D and Levine, V . 2000: Extended benefits and the duration of UI spells: Evidence from the New Jersey extended benefit program. Journal of Public Economics 78 (1–2): 107–138.

Dantan, S and Murtin, F . 2012: Can public policy mitigate unemployment hysteresis? Evidence from OECD countries. OECD Working Paper.

De Serres, A, Murtin, F and de la Maisonneuve, C . 2012: Tackling unemployment in a weak post-crisis recovery: Policies to facilitate the return to work. OECD Economics Department Working Paper.

Diamond, P . 1982: Aggregate demand management in search equilibrium. Journal of Political Economy 90 (5): 881–894.

Dyke, A, Heinrich, CJ, Mueser, PR, Troske, KR and Jeon, K-S . 2006: The effects of welfare-to-work program activities on labor market outcomes. Journal of Labor Economics, University of Chicago Press 24 (3): 567–608.

Elmeskov, J and MacFarlan, M . 1993: Unemployment persistence. OECD Economic Studies, No. 21, OECD: Paris.

Elmeskov, J, Martin, J and Scarpetta, S . 1998: Key lessons for labour market reforms: Evidence from OECD countries’ experiences. Swedish Economic Policy Review 5 (2): 205–252.

Elsby, M, Hobijn, B and Sahin, A . 2008: Unemployment dynamics in the OECD. NBER Working Paper no. 14617.

Elsby, M, Hobijn, B and Sahin, A . 2010: The labor market in the great recession. Federal Reserve Bank.

Fiori, G, Nicoletti, G, Scarpetta, S and Schiantarelli, F . 2007: Employment outcomes and the interaction between product and labor market deregulation: Are they substitutes or complements? IZA Discussion Papers 2770, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Forslund, A and Krueger, A . 2010: Did active labour market policies help Sweden rebound from the depression of the early 1990s? NBER Chapters. In: Reforming the Welfare State: Recovery and Beyond in Sweden. National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 159–187, Cambridge: MA.

Friedlander, D and Burtless, G . 1996: Five years after: the long-term effects of welfare-to-work programs. Russell Sage Foundation: New York.

Furceri, D and Mourougane, A . 2009: The effects of fiscal policy on output: A DSGE analysis. OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 770, OECD: Paris.

Garcia-Perez, JI, Jimenez-Martin, S and Sanchez-Martin, A . 2010: Financial incentives, individual heterogeneity and the transitions to retirement of employed and unemployed workers. Preliminary Version.

Gerfin, M and Lechner, M . 2002: A microeconometric evaluation of the active labour market policy in Switzerland. Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society 112 (482): 854–893.

Griffith, R, Harrison, R and Macartney, G . 2007: Product market reforms, labour market institutions and unemployment. Economic Journal 117 (March): C142–C166.

Guichard, S and Rusticelli, E . 2010: Assessing the impact of the financial crisis on structural unemployment in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 767, OECD: Paris.

Hotz, VJ and Scholz, JK . 2000: Not perfect, but still pretty good: The EITC and other policies to support the U.S. low-wage labour market. OECD Economic Studies 31 (II): 25–42.

Katz, L and Meyer, B . 1990: The impact of the potential duration of unemployment benefits on the duration of unemployment. Journal of Public Economics 41 (1): 45–72.

Kongsrud, PM and Wanner, I . 2005: The impact of structural policies on trade-related adjustment and the shift to services. OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 427, OECD: Paris.

Layard, R, Nickell, S and Jackman, R . 1991: Unemployment, macroeconomic performance and the labour market. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

Lindbeck, A . 1995: Welfare states disincentives with endogenous habits and norms. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 97 (4): 477–494.

Ljungqvist, L and Sargent, TJ . 1998: The European unemployment dilemma. The Journal of Political Economy 106 (3): 514–550.

Machin, S and Manning, A . 1999: The causes and consequences of long-term unemployment in Europe. Handbook of Labor Economics 3 (3): 3085–3139. Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Mortensen, D . 1986: Job search and labor market analysis. In: Ashenfelter, O and Layard, R (eds). Chapter 15 of Handbook of Labor Economics Vol. 2, Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Mortensen, D and Pissarides, C . 1994: Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. The Review of Economic Studies 61 (3): 397–415.

Murtin, F, de Serres, A and Hijzen, A . 2011: The ins and outs of unemployment: The role of labour market policies. OECD Working Paper.

Murtin, F and Robin, J-M . 2011: On the dynamics of unemployment – A cross-country comparison. OECD Working Paper.

Nickell, S . 1990: Unemployment: A survey. Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society 100 (401): 391–439.

Nickell, S . 1998: Unemployment: Questions and some answers. The Economic Journal 108 (448): 802–816.

Nicoletti, G and Scarpetta, S . 2005: Product market reforms and employment in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 472, OECD Publishing.

OECD. 1994: OECD employment outlook. OECD Publishing: Paris.

OECD. 2006: OECD employment outlook. OECD Publishing: Paris.

OECD. 2009: OECD employment outlook. OECD Publishing: Paris.

OECD. 2010a: OECD employment outlook. OECD Publishing: Paris.

OECD. 2010b: Off to a good start? Jobs for youth. OECD Publishing: Paris.

OECD. 2011: OECD economic outlook. OECD Publishing: Paris.

Pissarides, C . 1990: Equilibrium unemployment theory. Blackwell: Oxford.

Rogerson, R and Shimer, R . 2010: Search in macroeconomic models of the labor market. In: Ashenfelter, O and Card, D (eds). Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 4A, pp. 619–700, Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Schulhofer-Wohl, S . 2010: Negative equity does not reduce homeowners’ mobility. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Working Paper no. 682.

Shimer, R . 2005: The cyclical behavior of equilibrium unemployment and vacancies. The American Economic Review 95 (1): 25–49.

Shimer, R . 2007: Reassessing the ins and outs of unemployment. NBER Working Paper no. 13421.

Valletta, R and Kuang, K . 2010: Extended unemployment and UI benefits. FRBSF Economic Letter 2010–12 (19 April).

Visser, J . 2009: Database on institutional characteristics of trade unions, wage setting, state intervention and social pacts in 34 countries between 1960 and 2007. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies online database.

Yellen, J . 2010: The outlook for the economy and inflation, and the case for federal reserve independence. FRBSF Economic Letter, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (29 March).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andrea Bassanini, Romain Duval, Jørgen Elmeskov, Alexander Hijzen, Rafal Kierzenkowski, John Martin, Giuseppe Nicoletti, Pier Carlo Padoan, Mauro Pisu, Jean-Marc Robin, Stefano Scarpetta, Jean-Luc Schneider, Paul Swaim, as well as two anonymous referees for their valuable comments. Irene Sinha is gratefully acknowledged for technical assistance and editorial support. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Serres, A., Murtin, F. & De La Maisonneuve, C. Policies to Facilitate the Return to Work. Comp Econ Stud 54, 5–42 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2012.8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2012.8