Abstract

Lowering of underwriting standards may have contributed much to the unprecedented recent rise and subsequent fall of mortgage volumes and house prices. Conventional data do not satisfactorily measure aggregate underwriting standards over the past decade: the easing and then tightening of underwriting, inside and especially outside of banks, was likely much more extensive than they indicate. Given mortgage market developments since the mid-1990s, the method of principal components produces a superior indicator of mortgage underwriting standards. We show that the resulting indicator better fits the variation over time in the laxity and tightness of underwriting. Based on a vector auto-regression, we then show how conditions affected underwriting standards. The results also show that our new indicator of underwriting helps account for the behavior of mortgage volumes, house prices, and gross domestic product during the recent boom in mortgage and housing markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Because the inflation rate was so steady relative to that of the percentage changes in nominal house prices over this period, the correlation between the percentage changes in nominal and real house price was over 0.99.

Risk-based scores that indicate the likelihood of borrower default.

A change in the law during 2008 attempted to outlaw the practice, presumably because the default rate on such mortgages was proving already to be much higher than on other FHA loans.

Appendix I lists the questions and answers for the Federal Reserve's and for the OCC's recent surveys about residential mortgage underwriting. Note that the Federal Reserve includes mortgage interest rates in its question about underwriting standards.

The OCC reports data for the first quarter of each year. To obtain the data for the other quarters, we linearly interpolated between the values reported for the first quarter. This almost guarantees that the OCC data here will be smoother and have more measurement error than the Federal Reserve data.

The Demyanyk-Hemert data cover 1997 through 2006:Q2. We set observations before 1997 equal to the 1997:Q1 value. For the quarterly values beginning with 2006:Q3, we added 0.75 to the prior quarter. Beginning with 2007:Q3, for each ensuing pair of quarters, we subtracted 1, then, 2 and then 3 units.

The PC method is theoretically the optimal linear scheme, in terms of minimizing mean square errors, for generating a few (say, one) data series from many more (say, five) series. In that sense, it is a method to reduce the number of variables to be analyzed. The PC method is nonparametric and it requires no hypothesis about data probability distributions. By construction, the average value of the first PC here is zero.

The thrust of the results were not very sensitive to a number of alternative specifications. For example, the results were not much affected by substituting real for nominal house price growth.

References

Demyanyk, Yuliya, and Van Hemert, Otto . Forthcoming. “Understanding the Subprime Mortgage Crisis,” available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1020396.

Federal Reserve, 2009. “The April 2009 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices,” Washington, D.C., May, www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/SnLoanSurvey/200905.

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 2008. “Survey of Credit Underwriting Practices 2008,” Washington, D.C., June, www.occ.treas.gov/cusurvey/2008UnderwritingSurvey.pdf.

Sherlund, Shane M. 2008. “The Past, Present, and Future of Subprime Mortgages,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series No. 2008–63. Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs. Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C.

Additional information

This paper was the winner of NABE's Edmund A. Mennis Contributed Paper Award for 2009.

*James A. Wilcox is the Lowrey Professor of Financial Institutions at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. He has published widely on banking and credit unions, on housing and mortgage markets, on monetary policy, and on interest rates. His articles have been published in the top academic economics and finance journals. He teaches courses on macroeconomics, on financial markets and institutions, and on risk management at financial institutions and has won several awards for his teaching. He has also served as Chair of the Finance Group at the Haas School. From 1999–2001, he was the Chief Economist at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Previously, he served as the senior economist for monetary policy and macroeconomics for the President's Council of Economic Advisers and as an economist for the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. He is a Fellow of the Wharton Financial Institutions Center and a founding Fellow of the Filene Research Institute. He received his Ph.D. in economics from Northwestern University.

Appendices

Appendix A

The Federal Reserve and the OCC Surveys of Banks’ Underwriting Standards

In their separate surveys, the Federal Reserve and the OCC ask about banks’ mortgage underwriting standards.

The Federal Reserve conducts a “Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices at Selected Large Banks in the United States.” The sample of banks “is selected from among the largest banks in each Federal Reserve District. Large banks are defined as those with total domestic assets of $20 billion or more as of December 31, 2008. The combined assets of the 31 large banks totaled $6.2 trillion, compared with $6.5 trillion for the entire panel of 56 banks, and 10.7 trillion for all domestically chartered, federally insured commercial banks.” (Source: April 2009 survey results report.)

In the April 2009 survey the Federal Reserve asked the following question:

“Over the past three months, how have your bank's credit standards for approving applications from individuals for mortgage loans to purchase homes changed?” In earlier periods, the questions typically did not distinguish between prime and other applicants.

The survey gives banks the following five choices for their responses: Tightened considerably, tightened somewhat, remained basically unchanged, eased somewhat, or eased considerably.

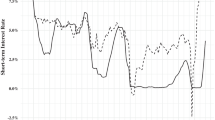

The Federal Reserve, and many other sources, commonly report an aggregate measure of net percentage tightening that is calculated as the sum of the shares of banks tightening considerably and tightening somewhat (each equally weighted) minus the sum of the shares of banks easing somewhat and easing considerably (each equally weighted).

The OCC conducts an annual “Survey of Credit Underwriting Standards.” “The 2008 survey included examiner assessments of credit underwriting standards at the 62 largest national banks. This population covers loans totaling $3.7 trillion as of December 2007, approximately 83 percent of total loans in the national banking system.” (Source: June 2008 survey.)

In 2008, the survey included assessments of the change in underwriting standards in residential real estate loan portfolios for the 55 banks engaged in this type of lending among the 62 in the survey. The survey gives examiners the following three choices for their responses: tightened, unchanged, and eased. We computed net percentage tightening as the share of banks tightening minus the share of banks easing.

Appendix B

Data Descriptions and Sources

GAP, the aggregate income variable, was calculated as the percentage difference between real GDP and real potential GDP. Real GDP was obtained from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and real potential GDP from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

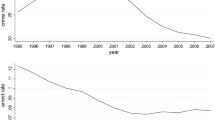

RHP was calculated adjusting nominal (that is, not adjusted for inflation) house prices using the GDP implicit deflator, which we obtained from the BEA. As data for aggregate house prices, we used the quarterly Freddie Mac conventional mortgage home price index.

GNHP, the variable used to measure the growth rate of nominal house prices, was calculated as the percentage change in house prices over the most recent four quarters.

IMORT, the mortgage interest rate, was measured as the quarterly, national-average, interest rate on 30-year, conventional, conforming FRMs as reported by Freddie Mac.

MORTPOT, our measure of mortgages outstanding, was calculated as the ratio (percent) of total, nominal, mortgage balances to nominal potential GDP. Mortgage balances were obtained from the Federal Reserve.

UWPC, the indicator of aggregate underwriting standards, was the first PC from five data series. The five series and the method of PC are described more fully in the text.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilcox, J. Underwriting, Mortgage Lending, and House Prices: 1996–2008. Bus Econ 44, 189–200 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/be.2009.26

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/be.2009.26