Abstract

The aim of this research is to examine to what extent the electoral support for radical right parties (RRPs) is driven by ‘policy voting’ and to compare this support with that of centre-right parties. Using the European Election Study 2019, we focus on six party systems: Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Austria, and the United Kingdom. Our analyses reveal that party preferences for RRPs are better explained by policy considerations than by other alternative explanations (e.g. by ‘globalization losers’ or ‘protest voting’). Additionally, the results show that although preferences for both party families are mainly rooted in ‘policy voting’, notable differences emerge when looking at the role of specific policy dimensions. Overall, these findings suggest that the support for RRPs cannot be understood fundamentally as a mere reaction against economic pauperization or political dissatisfaction but instead as an ideological decision based on rational choice models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In this article, we focus on 2019 European elections, studying in detail the electoral support for radical right parties (RRPs) in six countries: Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Austria, and the United Kingdom. We analyse to what extent the party preferences for RRPs are shaped by ‘policy voting’ compared to rival explanations. We also explore the similarities and differences between the electoral orientations towards RRPs and centre-right parties (CRPs), considering that these two party families are direct rivals in the electoral competition (Meguid 2005).

Since the emergence of RRPs during the 1980s in Europe, RRP constituencies have been examined mainly through two sets of explanations: the so-called ‘globalization losers’ and the ‘protest vote’ hypotheses. While the first explanation states that RRPs are supported fundamentally by the least-protected social sectors who have seen their statuses lowered due to capitalist globalization and global economic processes (Rodrik 2020; Swank and Betz 2003), the other suggests that support for RRPs is linked to political dissatisfaction and critical orientations towards the ways in which democracy and institutions work (Bélanger and Aarts 2006; Rydgren 2007). These two explanations are still dominant in the literature, even though empirical research has shown that their explanatory power is quite limited or at least not as conclusive as expected (Mudde 2007; van der Brug and Fennema 2009).

In general, it is accepted that policy preferences and attitudes play a key role in electoral behaviour. However, research on RRPs is not sufficiently sensitive to this issue, with notable exceptions, such as the works of van der Brug et al. (2000), and van der Brug and Fennema (2003, 2009), giving greater relevance to the two hypotheses mentioned above in comparative terms. However, there is nothing to suggest that RRP supporters are different than those of other parties in terms of the mechanisms that guide their voting decisions. This kind of exceptionalism, which understands electoral support for RRPs as an expression of socio-economic vulnerability or protest, does not have theoretical or empirical support in many cases. Nonetheless, these explanations have become commonplaces in the literature and are still often uncritically assumed to be true in all contexts.

Our purpose, therefore, is to apply the same methodological, analytical, and theoretical tools commonly used to study other party families to examine whether RRP support can be understood as an ideologically guided decision. This research consists of a fine-grained analysis of citizens’ electoral preferences towards RRPs to elucidate the importance of the ‘policy voting’ model in general and in comparison to the hegemonic explanations addressing the roles of socio-economic and protest factors.

This article is structured as follows. First, we present a theoretical review of the two main hegemonic explanations for RRP electoral support: the so-called ‘globalization losers’ and ‘protest vote’ hypotheses. As a complementary approach, we suggest some reasons that justify considering support for RRPs in the same way as we consider support for other parties: as a decision guided by ideological concerns. Based on this theoretical background, the third section presents several hypotheses. Next, we provide the case selection, variables, and models to test these hypotheses. We then present the multivariate analyses, and, at last, we conclude by discussing the implications of our findings.

The support for RRPs: precariousness, protest, or ideology?

This section provides an overview of the literature on RRP electoral support. From a critical point of view, we review approaches that conceive of support for RRPs as consequence of material deprivation (‘globalization losers’) or political disenchantment against political institutions and the status quo (‘protest voting’). In contrast with these two hegemonic views, we also offer some theoretical reasons to explain support for this party family as an ideological decision mainly guided by policy-based considerations.

On one hand, one of the most widely recognized explanations is the so-called ‘globalization losers’ thesis that interprets voting for RRPs as a direct consequence of modernization processes (Mudde 2007). To some extent, this is the current version of a much broader approach that emerged several decades ago (Bell 1964). Cyclically, this broader approach connects the steps in modernization processes and transformations (e.g. risk society, post-Fordism, post-industrial society, globalization, etc.) with the rise of RRPs. This view clearly echoes, but not explicitly reproduces, the fundamentals of a large portion of the literature focused on explaining the fascist experience in the interwar period. The research tradition on fascism has given a preeminent role to the changes in material conditions and their impacts on feelings of anxiety, anger, and isolation in explaining this phenomenon (Parsons 1942). Notwithstanding, as noted by Art (2013), it is necessary to be cautious when comparing fascism to modern RRPs, as their differences are more notable than their similarities.

Specifically, the ‘globalization losers’ thesis states that the least-protected and poorest sectors that have seen their status in society lowered due to capitalist globalization and economic transnational processes tend to support RRPs to a larger extent than other groups (Givens 2005; Rydgren 2007). It is assumed that these sectors blame immigrants to a greater extent than others and, therefore, opt for RRPs. From this point of view, these ‘globalization losers’ have a certain socio-demographic profile: unskilled workers or unemployed individuals with low levels of income and education (Arzheimer 2018). This explanation gained popularity during the 1990s in an attempt to explain the overproportionate presence of blue-collars workers in the RRP constituencies (Betz 1994; Betz and Immerfall 1998). More recently, sophisticated studies, such as Rodrik’s research (2018, 2020), have contributed to renewing this approach. However, while the value of this approach is evident, it only illuminates a part of the reality, and, consequently, some of its faults have been highlighted. In particular, some voices argue that the ‘globalization losers’ thesis fails in explaining the unequal levels of support for RRPs (both cross-country and within-country) (Art 2011; Mudde 2007). In other words, it does not provide appropriate answers for cases characterized by good economic contexts and high levels of support for RRPs or for cases characterized by bad economic contexts and low levels of support for RRPs (Art 2011). Moreover, it should be noted that when RRPs established themselves in the political arena, the likelihood of attracting voters from all social strata increased. However, we do not deny that the phenomenon in question has a material basis. What we suggest is that the explanatory power of socio-demographic factors is likely more modest than previously thought and uncritically assumed.

On the other hand (and closely connected with the abovementioned ‘globalization losers’ thesis), there is an approach that links RRP support to discontent with politics. In this way, RRP voting is conceived as a ‘protest vote’ against the political status quo (Bélanger and Aarts 2006; Betz 1994). In supporting radical options like those espoused by RRPs, voters’ main aims may be to punish the political establishment and the mainstream elites. Nevertheless, much of the research that originally examined (and validated) this theory suffered from serious theoretical and empirical deficiencies. In essence, little theoretical clarifications exist in these earlier works about what exactly the ‘protest vote’ concept means. At the same time, much of these studies were based on aprioristic assumptions, such as assuming that RRPs are ideological protest parties and that their supporters are also protest voters. However, if the objective is to assess electoral support from the point of view of the demand-side, the unit of analysis should not be the parties but the voters themselves. A well-founded critique to these works can be found in van der Brug and Fennema (2003, 2009).

Thus, the examination of the ‘protest vote’ hypothesis requires, above all, a clear, precise, and operational conceptualization. The proposal of Passarelli and Tuorto is a good starting point because it distinguishes between two simple features: (1) acting as a reaction against the establishment and (2) not being driven by policy preferences (2018, p. 131). In similar terms, van der Brug et al. note that “a protest voter is a rational voter whose objective is to demonstrate rejection of all other parties” (2000, p. 82). In sum, we conceptualize protest voters as those who basically express discontent but for whom ideological considerations or policy preferences are not important.

What if there is nothing exceptional but ideology? Support for RRPs and policy voting

The two explanations that we already presented (‘globalization losers’ and ‘protest voting’) share similar assumptions: that RRP support is not the result of ideological preferences but of rage, resentment, and rejection due to adverse economic situations and against the established political status quo. Both hypotheses share the common idea of crisis—economic or political—as an explanatory factor for RRP support.

However, there are no reasons for not assessing RRP voting behaviour with the same theoretical and methodological tools used for studying other political phenomena. Although a rich body of literature has considered policy preferences and policy voting since the seminal study of Downs (1958), research on RRPs has not being sufficiently sensitive to these approaches, except for a few notable works (Tillie and Fennema 1998; van der Brug and Fennema 2003, 2009; van der Brug et al. 2000). Within a rational choice paradigm, citizens will compare their preferences to the proposals made by parties and choose the programme closest to their own preferences. In this case, we focus on theories of prospective voting because RRPs generally do not have governing experience and cannot be evaluated by citizens within a retrospective model of voting. Prospective voting theories, particularly Downs’ approach, have been subject to criticism—mostly based on the idea that citizens should make an effort to research all information about the electoral proposals of different parties to analyse and compare their platforms, thereby deciding which party would be most beneficial from a personal point of view (Arnold 2002). It is difficult to imagine the average citizen assembling and reading all electoral programmes, comparing them in all their dimensions, and understanding how each of the proposals will personally affect him or her.

A lack of interest and limited political participation are hardly surprising. A personal investment to gain political information makes little sense in the case of collective elections, given the low probability a citizen has to influence the result and obtain personal profit because of his or her actions, as one vote will usually not change the final results. In this context, even if most citizens do not read electoral programme s personally, they can guide themselves using the information provided by the parties themselves and, of course, by other agents (e.g. mass media, opposing parties, or interest groups) (Lupia 1994). Taking into account questions related to the level of knowledge, comprehension, and interest in politics, we can distinguish three types of voters: sociological or psycho-sociological voters, economic voters, and limited-rationality voters (Lago et al. 2007). The present research assumes the third type: a voter with limited rationality guiding his or her decisions via heuristics and informative shortcuts.

Our research departs from the assumption that RRP supporters can be rational consumers in the electoral market who guide their voting decisions based on ideological and policy considerations. The policy voting framework must necessarily consider the main policy dimensions that structure European party systems and societies.

On one hand, the literature confirmed the existence of a socio-economic dimension in the traditional left–right axis, which comprises a continuum from interventionist and pro-redistributive to neo-liberal and free-market orientations. This dimension includes preferences about the economic organization of society, state intervention, privatization, and the redistribution of wealth and taxation, among others (Wagner and Kritzinger 2012).

On the other hand, the socio-cultural dimension, whose content is more extensive and diffuse, has gained prominence in recent decades (Hooghe et al. 2002; Oesch and Rennwald 2018). There are diverse conceptualizations of this dimension: Universalism–Particularism (Bornschier 2010), left libertarianism vs. right authoritarianism (Kitschelt and MacGann 1995), demarcation vs. integration (Kriesi et al. 2008), and GALTAN (Hooghe et al. 2002; Polk et al. 2017). Notably, the GALTAN label (Green, Alternative, and Libertarian versus Traditional, Authoritarian and Nationalist) is increasingly gaining acceptance in the literature. This conceptualization distinguishes between a GAL pole that is favourable to the expansion of personal freedoms (civil liberties, same-sex marriage, environmental protection, lifestyle choices, participatory democracy, etc.) and an antagonist TAN pole based on an exclusionary, traditionalist, and restricted conception of personal freedoms, morality, and national identity and a more strict defence of authority, law, and order (Hooghe et al. 2002). It is worth noting that the issues related to immigration—both for and against—are usually included in the GALTAN dimension.

A third dimension that also substantially affects the electoral competition has also been identified. This dimension is linked to attitudes towards the EU integration process and includes Europhile and Eurosceptic poles (which usually include mainstream and radical parties, respectively) (Hernández and Kriesi 2016; Marks and Edwards 2006).

In short, there are good reasons to examine the support for RRPs through the ‘policy voting’ framework. To this end, the main axes which structure the dimensionality of political competition in Europe must be considered.

Hypotheses

Several hypotheses can be derived from the previous theoretical framework. First, without denying the importance of alternative explanations, ‘policy voting’ can explain, to a large extent, the electoral preferences for RRPs (H1), in line with previous findings (van der Brug and Fennema, 2003, 2009). Hence, we expect the distance between the voter’s position and the party’s position on policy issues will be a good predictor of party preference, as outlined by classical spatial models (Downs 1958). Specifically, the shorter this distance is, the greater the likelihood of supporting RRPs. We therefore propose that policy considerations exert a greater effect on the electoral support for RRPs than variables related to ‘globalization losers’ and ‘protest voting’ explanations (H1).

Moving deeper into an analysis of policy voting, we argue that there might be some dimensions that are more salient for a limited-rationality voter than others. RRPs are almost always characterized by articulating their discourses in socio-cultural terms. Other findings have reduced the importance of the socio-economic dimension, highlighting how RRPs have blurred their socio-economic positions to attract broader support (Mudde 2007). As Bornschier notes, RRPs “articulate these grievances predominantly in cultural, not economic terms” (2010, p. 200). Although the renewed interest of RRPs in pro-redistributive positions was confirmed in line with so-called ‘welfare-chauvinism’ (Arzheimer 2013), we expect that the socio-economic dimension will be subordinated to socio-cultural dimensions (specifically, GALTAN and immigration, which will be treated separately). Similarly, while RRPs are usually linked to the idea of Euroscepticism, which refers broadly to negative attitudes to the European integration process (Gómez-Reino and Llamazares 2013), this dimension is expected to be secondary. In summary, H2 states that the GALTAN dimension and immigration have greater explanatory power than the socio-economic and EU integration dimensions in explaining party preferences for RRPs.

Moreover, to test the relative importance of ideological views in support for RRPs, we must compare the motivations for supporting RRPs with the motivations for supporting other parties. We restrict this comparison to mainstream CRPs since the literature has extensively shown that these two party families often directly compete on the same themes (Downes and Loveless 2018; Meguid 2005). Nevertheless, we anticipate the prominence of policy-based behaviour in both party families. We also expect some differences between the two groups regarding the impacts of particular policy dimensions.

On the one hand, the preferences for RRPs seem likely to be more strongly affected by the GALTAN dimension than preferences for CRPs (H3). The same difference is hypothesized for immigration: Compared to CRPs, electoral preferences for RRPs are more strongly affected by immigration (H4). Both hypotheses are theoretically sustained by the fact that these two dimensions are considered part of the RRP ideological core. Therefore, it makes sense to conceptualize preferences for RRPs as being driven to a larger extent by these policy preferences than preferences for CRPs.

On the other hand, support for RRPs has been traditionally linked to Eurosceptic statements, and these parties have also strategically emphasized this issue. Therefore, we also expect that the EU integration dimension will affect party preferences for RRPs to a larger extent than for CRPs (H5). Finally (H6), we assume that the socio-economic dimension is less important in explaining the party preferences for RRPs compared to CRPs, in line with the hypothesized secondary role of this policy dimension stated in H2.

Our general arguments in this research can, thus, be summarized as follows: The limited rationality of citizens who act based on their policy preferences can fundamentally explain RRP support. This is the same rational and ideological mechanism that explains the support for mainstream CRPs. However, several differences are expected to be found between these two party families in relation to specific policy dimensions.

Design and methodology

To test the hypotheses presented above, we focus on six different countries: Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Austria and United Kingdom, all of which have at least one relevant RRP established in the political system.Footnote 1 Table A1 in the Online Appendix shows the seven selected RRPs that achieved at least 5% of the vote in the 2019 European Elections and in the previous national elections (with the exception of UKIP). These parties share an ideological core consisting of nativism (a combination of nationalism and xenophobia) and authoritarianism (“the support for a strictly ordered society in which infringements of authority are to be punished severely”) (Mudde 2007, pp. 22–23). While some of these parties have been institutionalized for a long period of time (RN, LN, or FPÖ), others have emerged more recently (VOX, AfD, or FdI). Such heterogeneity will allow us to test the consistency of ‘policy voting’ across the different contexts despite the idiosyncratic factors that may contribute to RRP success in any context. The six CRPs were selected following similar criteria: All of them are established parties that share ideological values such as conservatism, neoliberalism, defence of the status quo, etc.

Our data come from the European Elections Study (EES) (Schmitt et al. 2019). The EES is a cross-sectional postelection survey that covers a wide range of attitudinal and socio-demographic parameters in the context of European elections. The main reason, and advantage, of choosing this database is that it provides us with cross-country data for the same moment in time and within the same electoral context, making comparison easier and more reliable should we use national elections surveys.

Our dependent variable is operationalized through the propensity to vote (PTV) for RRPs and CRPs. In PTV questions, all respondents were asked to indicate how likely they would be to vote for each party, with 0 representing ‘not at all probable’ and 10 indicating ‘very probable’. The use of PTV has been increasingly extended and is accepted as a good indicator of electoral preferences (van der Eijk et al. 2006). The main advantage of using PTV is the maximization of N, as almost all respondents express their views for all competing parties. Moreover, the effect of social desirability bias is strong among RRP voters, so such voters do not often declare their true voting choice (Werts et al. 2013), reducing the sample size even further.

To answer our research question (to what extent can electoral preferences for RRPs can be explained by ‘policy voting’ along with alternative explanations?), we applied the method originally proposed by Stimson (1985), which has been frequently used in political research (van der Brug et al. 2007; van der Eijk and Franklin 1996). This method consists of transforming the original data matrix into a ‘stacked’ matrix such that each respondent is represented by as many ‘cases’ as there are parties for which he or she was asked to express his or her PTV. Thus, the new cases represent a combination of the respondents and PTVs of each party.Footnote 2

Several independent variables are used to predict party preferences. To operationalize the factors related to ‘policy voting’, we perform a two-step process. First, to measure citizens’ policy preferences, we utilize a set of item statements in which the respondents indicate their agreement or disagreement towards particular policy proposals (see Table A3 in the Online Appendix). On the basis of previous research (Walczak et al. 2012) and theoretical considerations, we group these statements by their connections to the three main political dimensions reviewed in “What if there is nothing exceptional but ideology? Support for RRPs and policy voting” section: GALTAN, socio-economic, and EU integration. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out separately for each set of statements. The results confirm the consistence of the abovementioned three attitudinal dimensions in the six analysed countries (see Table A3 for details and robustness tests). Alongside the three attitudinal dimensions, we also considered the respondents’ positions on immigration policy. This issue is usually included within the GALTAN dimension, but in consideration of its importance for RRPs, we decided to examine immigration by itself.

Second, we extracted the parties’ positions on the four policy dimensions (GALTAN, socio-economic, EU integration, and immigration) using the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. 2020a; b) (see Table A4). Then, we calculated the absolute value of the distance between the positions of respondents and parties on each policy dimension.Footnote 3 In this model, the smaller the distance is (that it is, the greater the agreement between voters and parties), the higher the probability of voting for RRPs will be, if policy voting is in fact driving preferences for RRPs rather than alternative explanations.

The ‘protest voting’ model is operationalized through four items related to satisfaction with democracy in one’s own country and in the EU more broadly, as well as trust in the national and European parliament, which allowed a direct examination that was not possible with previous iterations of the survey. In comparative terms, we are now in a better position than previous works, which suffered from data limitations, to examine ‘protest voting’ (van der Brug et al. 2000; van der Brug and Fennema 2003, 2009).

To test the ‘globalization losers’ hypothesis, we included a set of socio-demographic variables: age, education, standard of living, and unemployment. We employed thee variable because previous findings identified ‘globalization losers’ to match a certain profile: young, unemployed, and with low levels of education and income (Arzheimer 2013, 2018).

Two other variables were included as controls: gender and party size. A portion of the literature considers men to represent ‘globalization losers’. However, an equal or greater quantity of women have also suffered from globalization. Consequently, we did not include gender within the ‘globalization losers’ framework but rather as a simple control variable. Finally, we consider it probable that voters employ strategic considerations—i.e. that between two parties, a voter is more likely to support the larger party. In this way, we operationalize the party size by taking the % of votes for each party in the national parliament prior to the 2019 European Elections (Döring and Manow 2019).

Regarding independent variables for which distance measures could not be obtained (i.e. all except GALTAN, socio-economic, EU integration, and immigration) or for which distance measures were unfeasible (e.g. party size), we performed a linear transformation of the original variables following the procedure explained in detail by van der Brug et al. (2007, pp. 43–45).Footnote 4 In essence, this procedure allowed us to add variables that are comparable across countries and parties to the stacked matrix.

This ‘stacked’ data matrix made it possible to simultaneously study the party preferences for the thirteen parties in the seven considered political systems. First, we conducted three different regressions including all thirteen parties, the seven RRPs, and the six CRPs. These regressions enabled an exploratory comparison of differences in the effect parameters. Second, we considered all the parties and estimated the interaction terms for RRPs and policy issue distances to discern whether party-specific considerations exist at the voter level.

Results

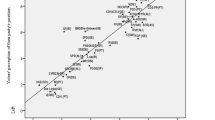

Table 1 presents the three different OLS regression modelsFootnote 5 through which PTV was predicted by the various independent variables we previously operationalized. The first model estimated the PTV for all 13 RRPs and CRPs, while the other two include only the RRPs (seven parties) and CRPs (six parties). Country dummies were added to the models in order to control for national differences and potentially omitted variables, thereby removing idiosyncratic explanations from the models. We also estimated these models without country dummies, and the findings were essentially the same (see Table A5). Notably, as the independent variables were inductively created through a linear transformation (except for those related to the ‘policy voting’ model), the standardized coefficients were directly comparable across countries and parties. As a consequence of this transformation, the standardized coefficients were generally positive. Thus, no conclusions could be drawn about directionality but only about the intensity of the effects. However, this is not a limitation since the present approach allowed us to satisfactorily test the proposed hypotheses.

In model 1, a dummy variable that distinguishes RRPs from CRPS is included to help discern whether a substantial different exists between these two party families regarding their electoral attractiveness. The significantly positive coefficient here (0.068) indicates that, after controlling for the rest of the independent variables, electoral preferences for RRPs remain, on average, higher than preferences for CRPs. Although limited in its intensity, this finding points to the growing relevance of RRPs, as well as the intense competition between RRPs and CRPs, as noted in the literature (Downes and Loveless 2018). However, it should be noted that we chose variables traditionally linked to voting for RRPS. Thus, it is possible that running the models with other factors would not indicate the primacy of RRPs over CRPs.

By examining which factors determine the electoral preferences for all 13 parties, we can see that party size has the strongest coefficient (0.199, significant at a < 0.001 level). This is a stable finding noted in previous research (van der Brug and Fennema 2003, 2009) and can be interpreted as proof of pragmatic voting: Voters find larger parties more attractive than smaller parties. The second strongest predictor is immigration (− 0.176). In the hypothesis, the shorter the distance is between one’s voting position and the party’s position, the more attractive the party will be. The GALTAN dimension also seems to be relevant in the same way, but with a much smaller coefficient. In turn, though many of the other factors related to ‘globalization losers’ and ‘protest voting’ are also significant, these factors have a more limited impact. Overall, when considered together, electoral preferences for both party families seem to be guided mainly by ideological and pragmatic orientations.

Next, we take a closer look at the two groups separately. As shown in model 2, the three policy factors—GALTAN, immigration, and EU integration—exert a significant and substantial effect on preferences for RRPs. At the same time, the contribution of socio-demographic and protest factors is quite modest and far from that of the ‘policy voting’ model. In short, our findings are in line with the expectations raised in H1 since party preferences for the seven RRPs are better explained by ‘policy voting’ than by ‘globalization losers’ or ‘protest voting’ explanations. In particular, the refusal of the later thesis is sustained by the fact that the second element of the ‘protest voting’ conceptualization—that it is, the lack of considerable policy preferences—is absent. Moreover, the ways in which voters are attracted by RRPs seem to be strongly conditioned by the size of the party, which implies that such voters tend to support larger parties more than smaller by carrying out pragmatic strategic calculations.

Therefore, our findings indicate the prominent role of ‘policy voting’ in shaping voter preferences for RRPs. This result clarifies that support for RRPs is primarily driven by ideological considerations. Hence, RRPs do not appear to be exceptional, as they are nurtured by the same orientations that affect CRPs. These results point in the same direction as previous empirical studies that assessed the same question (Tillie and Fennema 1998; van der Brug et al. 2000; van der Brug and Fennema 2003, 2009).

When comparing models 2 and 3 (see Table 1), we see that explanatory preeminence of ‘policy voting’ against alternative explanations exists for both RRPs and CRPs. However, some differences emerge. Surprisingly, only one dimension is significant for CRPs, as expected by the spatial voting models (immigration, with a beta coefficient of − 0.136), while variables such as standard of living, satisfaction with democracy in the country and the EU, and trust in the national parliament are also significant with high coefficients. In comparative terms, the ‘policy voting’ model has greater importance for RRPs than for CRPs.

Having confirmed the role of ‘policy voting’ compared to alternative explanations, we next examine the specific impact of each policy dimension. Here, the expectations are that the contributions of the different dimensions will be unequal. As proposed in H2, model 2 in Table 1 shows that the policy issues that exert the strongest effects over preferences for RRPs have a socio-cultural nature: GALTAN and immigration (− 0.200 and − 0.150 at a 0.001 level, respectively). Conversely, the economic left–right is statistically significant but in the opposite hypothesized direction (that is, the divergence between voters and parties in this dimension significantly predicts party preferences). These findings support H2 since they confirm the prominence of socio-cultural issues over socio-economic judgments (Bornschier 2010; Mudde 2007). This hypothesis is also confirmed for EU integration: although statistically significant, EU integration is of secondary importance compared to the other socio-cultural dimensions.

Table 1 presents exploratory comparisons. We next turn to the question of whether policy dimensions have effects that are significantly different between RRPs and CRPs. The stacked nature of the data matrix allowed us to perform this analytical comparison in a more systematic way. For this purpose, we ran two models for all 13 studied parties and included several interaction terms between RRPs and issue distances (Table 2). Both models also contain all the other independent variables used previously, but these variables are not shown here because our interest is only on the interaction effects of policy dimensions. Since interaction terms do not allow the use of standardized coefficients, unstandardized coefficients were used instead.

On the one hand, model 4 shows the interactions between the seven RRPs (as a dummy variable) and the policy dimensions, as well as the main effects. To understand the meaning of the interaction terms, the main effects must be considered. For example, the main effect of immigration is − 0.306, which implies that, in the hypothesized direction, the shorter the distance is between voters and parties on this issue, the larger the propensity will be to vote for such parties. The positive interaction effect of immigration indicates that the effect of this issue is weaker for RRPs than for CRPs. Hence, the unstandardized effect for RRPs is − 0.141 (− 0.306 + 0.165). This is a surprising finding that runs contrary to H4, where we hypothesizd that immigration would affect the preferences for RRPs to a larger extent than for CRPs. Similarly, we found a statistically significant difference in the socio-economic left/right. This issue was also found to be weaker for RRPs than for CRPs. Here, the result is in line with the original expectation suggested in H6. The negative interaction effect for the GALTAN dimension shows that the effect of this issue is somewhat stronger for RRPs than for CRPS, which validates H3 and supports the idea of conceiving the preferences for these parties mainly as cultural backlash (Bornschier 2010). Finally, the interaction term for EU integration shows that this issue is also more relevant for explaining party preferences for RRPs than for CRPs, but with a low significance level.

Model 5 shows the same results as above but for each of the seven RRPs as dummies. In this respect, several stable paths emerge, in line with the findings derived from model 4. First, the effect of distance on the GALTAN dimension is significantly stronger for five RRPs (VOX, AfD, LN, FdI, and FPÖ) than for the CRPs. Second, the socio-economic left/right has a weaker impact on party preferences for all the analysed RRPs (except for VOX) than for the rest of the CRPs. This result reinforces the secondary role of socio-economic stances in orienting support for RRPs, as stated in H6. Despite a similar result in model 4, the weaker effect of immigration distance for all RRPs than for the rest of the CRPs is surprising. While the coefficient of the main effects is − 0.319, the interaction terms have positive significant coefficients. This is a remarkable finding since it highlights that immigration is the main dimension in which the electoral battle is being fought between RRPs and CRPs. In light of this fact, it makes sense that RRPs emphasize immigration statements in an attempt to attract supporters of traditional CRPs who value this dimension. Finally, EU integration more strongly impacts support for some RRPs—RN, AfD, FPÖ, and UKIP—than support for CRPs. The importance of the EU integration dimension in the electoral bases of these four parties was already noted.

Conclusions: limited-rationality voters choosing based on policy preferences

Since RRPs emerged during the 1980s in Western Europe, significant efforts have been made to examine their constituencies. This article addresses to what extent the electoral support for RRPs might be driven by ‘policy voting’ in six party systems (Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Austria, and United Kingdom). In this way, our work is aligned with approaches that encourage researchers to assess RRPs with the same theoretical and methodological tools used for studying other political phenomena.

Empirical analyses show that preferences for RRPs are strongly determined by policy considerations. In view of this, it could be possible to fundamentally consider RRP supporters as rational consumers in the electoral market who guide their voting decisions through rational cognitive mechanisms. In this sense, the concept of limited rationality is useful for understanding this process since electoral support for these parties appears to be oriented by ‘packages’ of attitudes and beliefs about policy issues. Considering these ideological ‘packages’, citizens compare their own beliefs with those of the parties and cast their votes accordingly. More interestingly, the ‘policy voting’ model has greater explanatory power than the two main alternative hypotheses of ‘globalization losers’ and ‘protest voting’, which conceive of RRP support as a direct consequence of economic precariousness and political alienation. In light of our findings, and contrary to much of the literature, there is no empirical evidence for accepting these explanations (at least not among the analysed cases). These results highlight the need to be more cautious and not take these categories for granted. The decline of socio-demographic factors in structuring voting decisions is a process largely confirmed in contemporary societies and seems to also affect RRPs. This does not imply that material conditions are not important in supporting these parties but only that ideological concerns seem to matter more. Moreover, protest voting is more likely to occur during times of party emergence, rather than when the parties are already established (as in the case of most of the analysed RRPs).

Notable prior studies provided evidence supporting the importance of ‘policy voting’ for RRPs but mainly focused on the super-dimensions of left/right (van der Brug and Fennema 2003, 2009). As an added value, our research highlights the differential impact of specific policy dimensions. In this study, we showed that socio-cultural spheres (the GALTAN dimension and immigration) are crucial, while the socio-economic dimension does not exert a significant effect on party preferences for RRPs. Consequently, it makes sense that RRPs emphasize socio-cultural issues from the perspective of their ideological supply since the potential voters of RRPs are more receptive to these themes.

On the other hand, important similarities and differences between RRPs and CRPs were found. First, policy issues play a key role in explaining preferences for both party groups, which implies that the attractiveness of RRPs is not ‘exceptional’ but rooted in the same concepts as their main competitors, CRPs. Paradoxically, contrary to what might be expected, the impact of ‘policy voting’ was found to be weaker for CRPs than for RRPs in relative terms (only immigration was a strong predictor for CRPs). Second, when comparing both party families more systematically, significant differences emerged regarding the weight of each policy dimension. Preferences for RRPs were found to be more strongly determined by the GALTAN dimension and EU integration than preferences for CRPs. In contrast, the socio-economic left/right and immigration were found to exert weaker effects on RPPs than on CRPS. These results were similar when examining the RRPs one by one. In general, these findings provide a good overview of the competitive landscape of both party families and, more specifically, highlight the crucial nature of the immigration issue.

Our analyses do not come without limitations. Given the stacked nature of the data and the linear transformation of the independent variables, directional effects cannot be inferred. However, this is an implicit deficit of the research design and does not preclude achievement of the initial objectives. Likewise, we only examined six European countries due to data limitations, but future research should include as many countries as possible to shed light on whether ‘policy voting’ is also preeminent for other European RRPs.

To conclude, we demonstrated that electoral support for RRPs is a decision fundamentally guided by ideological orientations, with socio-economic and protest-related factors playing only a minor role. Our findings have several implications and suggest new questions and avenues for future research. On the one hand, from the perspective of policy making, political actors should not undervalue or consider support for RRPs as ephemeral or unsubstantial. On the other hand, future research should stop considering RRPs as a pathology of contemporary democracies but rather as a direct consequence of tensions that can be addressed by the same approaches traditionally used in Political Science.

Notes

One may ask, “why not also choose other Western European countries?” We selected our sample based on the fact that only for these six countries does the EES offer all the items that are necessary to empirically construct policy dimensions at the voter level. Future examinations could apply this analytical approach to explore more countries and parties.

To carry out this transformation, the Stata package PTVTOOLS was used (De Sio and Franklin 2011).

Previous studies tested the ‘policy voting’ model by calculating the distance between the respondent’s positions and the respondent’s perceptions of the positions of parties on specific issues. However, as suggested by Bakker, Jolly, and Polk (2020a, b), using an external measure of party position can obtain more precise data since voters often do not have solid opinions regarding parties’ positions on specific issues. Furthermore, similar works previously focused only on the left–right dimension due to data limitations. Offering a richer picture of ‘policy voting’ by distinguishing between specific policy issues is an added value of our research. To calculate the distances between voters and parties, the scores were standardized.

This procedure involved carrying out a series of bivariate regressions to predict the PTV for each original independent variable. The predicted values, known as y-hats, were saved and used as the new independent variables.

We used the robust estimate of variance and the ‘cluster’ option to adjust for the dependency among observations for the same respondents. Hence, each respondent was defined as a separate cluster.

References

Arnold, C. 2002. How two-level entrepreneurship works: A case study of ratcheting up a Europe-wide employment strategy. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Art, D. 2011. Inside the radical right. The development and impact of anti-immigrant parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Art, D. 2013. Why 2013 is not 1933: The radical right in Europe. Current History 112 (752): 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2013.112.752.88.

Arzheimer, K. 2013. Working class parties 2.0? Competition between centre-left and extreme right parties. In Class politics and the radical right, ed. J. Rydgren, 75–90. London: Routledge.

Arzheimer, K. 2018. Explaining electoral support for the radical right. In The Oxford handbook of the radical right, ed. J. Rydgren, 1–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bakker, R., L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, G. Marks, J. Polk, J. Rovny, and M.A. Vachudova. 2020. 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. Chapel Hill.

Bakker, R., S. Jolly, and J. Polk. 2020b. Multidimensional incongruence, political disaffection, and support for anti-establishment parties. Journal of European Public Policy 27 (2): 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1701534.

Bélanger, É., and K. Aarts. 2006. Explaining the rise of the LPF: Issues, discontent, and the 2002 Dutch election. Acta Politica 41: 4–20.

Bell, D. 1964. The radical right. New Jersey: Transactions Publishers.

Betz, H.-G. 1994. Radical right- wing populism in Western Europe. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Betz, H.-G., and S. Immerfall. 1998. New politics of the right: Neo-populist parties and movements in established democracies. Basingtoke: MacMillan.

Bornschier, S. 2010. The new cultural divide and the two-dimensional political space in Western Europe. West European Politics 33 (3): 419–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402381003654387.

De Sio, L., and M. Franklin. 2011. ‘PTVTOOLS: Stata module containing various tools for PTV analysis’. Boston College Department of Economics.

Döring, H., and P. Manow. 2019. Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. http://www.parlgov.org/.

Downes, J.F., and M. Loveless. 2018. Centre right and radical right party competition in Europe: Strategic emphasis on immigration, anti-incumbency, and economic crisis. Electoral Studies 54: 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.05.008.

Downs, A. 1958. An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Givens, T. 2005. Voting radical right in Western Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gómez-Reino, M., and I. Llamazares. 2013. The populist radical right and European integration: A comparative analysis of party-voter links. West European Politics 36 (4): 789–816. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2013.783354.

Hernández, E., and H. Kriesi. 2016. Turning your back on the EU. The role of Eurosceptic parties in the 2014 European Parliament elections. Electoral Studies 44: 515–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.013.

Hooghe, L., G. Marks, and C.J. Wilson. 2002. Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 965–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310.

Kitschelt, H., and A. MacGann. 1995. The radical right in Western Europe: A comparative analysis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2008. West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lago, I., J.R. Montero, and M. Torcal. 2007. The 2006 regional election in Catalonia: Exit, voice, and electoral market failures. South European Society and Politics 12 (2): 221–235.

Lupia, A. 1994. The effect of information on voting behavior and electoral outcomes: An experimental study of direct legislation. Public Choice 78: 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01053366.

Marks, G., and E. Edwards. 2006. Party competition and european integration in the East and West different structure same causality. Comparative Political Studies 39 (2): 155–175.

Meguid, B.M. 2005. Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in Niche Party Success. American Political Science Review 99 (3): 347–359.

Mudde, C. 2007. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oesch, D., and L. Rennwald. 2018. Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: Class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right. European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 783–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12259.

Parsons, T. 1942. Some sociological aspects of the fascist movements. Social Forces 138–147.

Passarelli, G., and D. Tuorto. 2018. The Five Star Movement: Purely a matter of protest? The rise of a new party between political discontent and reasoned voting. Party Politics 24 (2): 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068816642809.

Polk, J., J. Rovny, R. Bakker, E. Edwards, L. Hooghe, S. Jolly, and M. Zilovic. 2017. Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. Research and Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686915.

Rodrik, D. 2018. Populism and the economics of globalization. Journal of International Business Policy. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-0001-4.

Rodrik, D. 2020. Why does globalization fuel populism? Economics, culture, and the rise of right-wing populism (National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series No. 27526).

Rydgren, J. 2007. The sociology of the radical right. Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752.

Schmitt, H. et al. 2019. European parliament election study 2019. Voter Study. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13473.

Stimson, J.A. 1985. Regression in space and time: A statistical essay. American Journal of Political Science 29: 914–947.

Swank, D., and H.-G. Betz. 2003. Globalization, the welfare state and right-wing populism in Western Europe. Socio-Economic Review 1 (2): 215–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/soceco/1.2.215.

Tillie, J., and M. Fennema. 1998. A rational choice for the extreme righ. Acta Politica 3 (33): 223–249.

van der Brug, W., and M. Fennema. 2003. Protest or mainstream? How the European anti-immigrant parties developed into two separate groups by 1999. European Journal of Political Research 42 (1): 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00074.

van der Brug, W., and M. Fennema. 2009. The support base of radical right parties in the enlarged European Union. Journal of European Integration 31 (5): 589–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036330903145930.

van der Eijk, C., and M. Franklin. 1996. Choosing Europe? The European electorate and national politics in the face of union. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

van der Brug, W., M. Fennema, and J. Tillie. 2000. Anti-immigrant parties in Europe: Ideological or protest vote? European Journal of Political Research 37 (1): 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00505.

van der Brug, W., C. van der Eijk, and M. Franklin. 2007. The economy and the vote economic conditions and elections in fifteen countries economic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van der Eijk, C., W. van der Brug, M. Kroh, and M. Franklin. 2006. Rethinking the dependent variable in voting behavior: On the measurement and analysis of electoral utilities. Electoral Studies 25 (3): 424–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2005.06.012.

Wagner, M., and S. Kritzinger. 2012. Ideological dimensions and vote choice: Age group differences in Austria. Electoral Studies 31 (2): 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2011.11.008.

Walczak, A., W. van der Brug, and C.E. de Vries. 2012. Long- and short-term determinants of party preferences: Inter-generational differences in Western and East Central Europe. Electoral Studies 31 (2): 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2011.11.007.

Werts, H., P. Scheepers, and M. Lubbers. 2013. Euro-scepticism and radical right-wing voting in Europe, 2002–2008: Social cleavages, socio-political attitudes and contextual characteristics determining voting for the radical right. European Union Politics 14 (2): 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512469287.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Iván Llamazares, Mariana Sendra and Jorge Ramos for their valuable comments and suggestions on previous versions of this article. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

This work was supported by ‘Ayudas para la Formación de Profesorado Universitario’ (FPU, Ministry of Education, Government of Spain [FPU16/04643]. Funding for open access publishing: Universidad Pablo de Olavide/CBUA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ortiz Barquero, P., Ruiz Jiménez, A.M. & González-Fernández, M.T. Ideological voting for radical right parties in Europe. Acta Polit 57, 644–661 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-021-00213-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-021-00213-8