Abstract

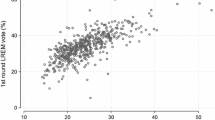

The 2017 presidential election represents a turning point in French electoral politics. It was marked by the poor performance of the main governing parties’ candidates and the victory of political newcomer Emmanuel Macron. More surprisingly, four candidates with clearly distinct policy lines were neck and neck in the first round. This article sheds light on this outcome and assesses its consequences for the French party system. We sketch alternative scenarios regarding the format and content of the emerging party system. Using geometrical analyses on data from the French Election Study 2017 (Gougou and Sauger 2017), we show that the current political space is structured by two main conflict dimensions: the first and dominating dimension sets an anti-immigration/authoritarian pole against a pro-immigration/libertarian pole; the second pits an ecologist/interventionist pole against a productivist/neoliberal pole.

Source: Constitutional Council. Note: Socialist candidate François Mitterrand was endorsed by the Communist Party in 1965 and 1974

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Recent work has demonstrated that French mainstream parties have been eager to take up issues associated with niche parties (Meguid 2008; Brouard et al. 2012; Persico 2015), which is what Sarkozy successfully did with immigration in 2007 (Sauger 2007; Spoon 2008). Yet, the 2017 election shows that mainstream parties will stop taking up those issues if niche parties no longer politicize them.

Let us not forget that the early days of the Fifth Republic proved how a new president with a new party could radically transform the political space.

We performed a specific multiple correspondence analysis (using Spad). This technique allows us to record non-responses as ‘passive modalities’: individuals with missing answers remain in the analysis, but missing values are ignored when determining distances between individuals (Le Roux and Rouanet 2004).

References

Alduy, C. 2017. Ce qu’ils disent vraiment: les politiques pris au mot. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Bartolini, S. 2007. The political mobilization of the European Left, 1860–1980: The class cleavage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bartolini, S., and P. Mair. 1990. Identity, competition and electoral availability: The stabilisation of European Electorates, 1885–1985. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benzécri, J.-P. 1992. Correspondence analysis handbook. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Bornschier, S. 2007. Social structure, collective identities, and patterns of conflict in party systems: Conceptualizing the formation and perpetuation of cleavages. In Politicising socio-cultural structures: Elite and mass perspectives on cleavages. Presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions Helsinki.

Bornschier, S. 2010. The new cultural divide and the two-dimensional political space in Western Europe. West European Politics 33 (3): 419–444.

Bornschier, S., and R. Lachat. 2009. The evolution of the French political space and party system. West European Politics 32 (2): 360–383.

Brouard, S., E. Grossman, and I. Guinaudeau. 2012. French party competition through the lens of electoral priorities. Revue française de science politique 62 (2): 255–276.

Chiche, J., B. Le Roux, P. Perrineau, and H. Rouanet. 2000. L’espace politique des électeurs français à la fin des années 1990. Nouveaux et anciens clivages, hétérogénéité des électoratsé. Revue française de science politique 50 (3): 463–488.

Cole, A. 2002. A strange affair: The 2002 presidential and parliamentary elections in France. Government and Opposition 37 (3): 317–342.

Dalton, R.J. 2009. Economics, environmentalism and party alignments: A note on partisan change in advanced industrial democracies. European Journal of Political Research 48 (2): 161–175.

Deegan-Krause, K. 2007. New dimensions of political cleavage. In Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, ed. R.J. Dalton, and H.-D. Klingemann, 538–556. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duverger, M. 1985. Le système politique français, 18th ed. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Gougou, F., and S. Labouret. 2011. Participation in the 2010 French regional elections: The minor impact of a change in the electoral calendar—A reply to Fauvelle-Aymar. French Politics 9 (3): 240–251.

Gougou, F., and S. Labouret. 2013. The end of tripartition? Revue française de science politique 63 (2): 279–302.

Gougou, F., and N. Sauger. 2017. The 2017 French Election Study (FES 2017): A post-electoral cross-sectional survey. French Politics 15(3).

Grunberg, G., and E. Schweisguth. 1997. Vers une tripartition de l’espace politique. In L’électeur a ses raisons, ed. D. Boy, and N. Mayer, 179–218. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Grunberg, G., and E. Schweisguth. 2003. La tripartition de l’espace politique. In Le vote de tous les refus. Les élections présidentielles et législatives de 2002, ed. P. Perrineau and C. Ysmal, 341–462. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2006. Parties, public opinion, and identity: A postfunctionalist theory of European integration.

Inglehart, R. 1984. The changing structure of political cleavages in Western Society. In Electoral change in advanced industrial democracies: Realignment or dealignment?, ed. P.A. Beck, S.C. Flanagan, and R.J. Dalton, 25–69. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kitschelt, H. 1994. The transformation of European social democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Höglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest. 2012. Political conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2006. Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956.

Kriesi, H., E. Grande, R. Lachat, M. Dolezal, S. Bornschier, and T. Frey. 2008. West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kuhn, R. 2002. The French presidential and parliamentary elections, 2002. Representation 39 (1): 44–46.

Labouret, S. 2016. Le Front national au second tour en 2015: une force qui demeure ‘impuissante’. In Groupement de recherches sur l’administration locale en Europe (Ed.), Les élections Locales Françaises 2014–2015. Antony: Le Moniteur.

Le Roux, B., and H. Rouanet. 1998. Interpreting axes in MCA: Method of the contributions of points and deviations. In Visualization of categorical data, ed. J. Blasius, and M. Greenacre. San Diego: Academic Press.

Le Roux, B., and H. Rouanet. 2004. Geometric data analysis: From correspondence analysis to structured data analysis. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Le Roux, B., and H. Rouanet. 2010. Multiple correspondence analysis. Los Angeles: Sage.

Mack, C.S. 2010. When political parties die: A cross-national analysis of disalignment and realignment, 1st ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Martin, P. 2007. Comment analyser les changements dans les systèmes partisans d’Europe occidentale depuis 1945? Revue internationale de politique comparée 14 (2): 263–280.

Martin, P. 2017. Un séisme politique. L’élection présidentielle de 2017. Commentaire 158: 249–264.

Meguid, B.M. 2008. Party competition between unequals: Strategies and electoral fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miguet, A. 2002. The French elections of 2002: After the earthquake, the Deluge. West European Politics 25 (4): 207–220.

Oesch, D. 2006. Redrawing the class map: Stratification and Institutions in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Oesch, D., and L. Rennwald. 2017. Electoral competition in Europe’s new tripolar political space: class voting for the left, centre-right and radical right (EUI Working Paper No. 02). Florence: European University Institute.

Persico, S. 2015. Co-optation or avoidance? Revue française de science politique 65 (3): 405–428.

Sauger, N. 2004. Entre survie, impasse et renouveau: les difficultés persistantes du centrisme français. Revue Française de Science Politique 54 (4): 697–714.

Sauger, N. 2007. The French presidential and legislative elections of 2007. West European Politics 30 (5): 1166–1175.

Shields, J. 2015. The Front National at the polls: Transformational elections or the status quo reaffirmed? French Politics 13 (4): 415–433.

Spoon, J.-J. 2008. Presidential and legislative elections in France, April–June 2007. Electoral Studies 27 (1): 155–160.

Tiberj, V. 2012. Two-axis politics: Values, votes and sociological cleavages in France (1988–2007). Revue française de science politique 62 (1): 67–103.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gougou, F., Persico, S. A new party system in the making? The 2017 French presidential election. Fr Polit 15, 303–321 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-017-0044-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-017-0044-7