Abstract

A star-shaped cyclometalated triruthenium complex 2(PF6)n (n = 3 and 4) with a triarylamine core was synthesized, which functions as a molecular switch with five well-separated redox states in both solution and film states. The single-crystal X-ray structure of 2(PF6)3 is presented. This complex displays four consecutive one-electron redox waves at +0.082, +0.31, +0.74, and +1.07 V vs Ag/AgCl. In each redox state, it shows significantly different NIR absorptions with λmax of 1590 nm for 24+, 1400 nm for 25+, 1060 nm for 26+, and 740 nm for 27+, respectively. Complex 24+ shows a single-line EPR signal at g = 2.060, while other redox states are all EPR inactive. The spin density distributions and NIR absorptions in different redox states were rationalized by DFT and TDDFT calculations. A vinyl-substituted triruthenium analogous 3(PF6)4 was prepared, which was successfully polymerized on ITO glass electrode surfaces by reductive electropolymerization. The obtained poly-3n+/ITO film was characterized by FTIR, AFM, and SEM analysis. It shows four well-defined redox couples and reversible multistate NIR electrochromism. In particular, a contrast ratio (ΔT%) up to 63% was achieved at the optic telecommunication wavelength (1550 nm).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Molecular switches can be reversibly shifted between two or more stable states in response to external stimuli1. Among them, electro-active compounds have received much interest as redox-driven molecular switches2, which show appealing functions such as information storage3,4,5, electrochromism6,7,8, electrofluorochromism9, and switching of molecular conductance10 and magnetism11.

Recent attention has been focusing on the design of smart and sophisticated switching molecules that can display multiple and consecutive redox processes at low potentials with each redox state being distinguished by specific readout signals12,13,14. This is particularly important for the application of these materials in information storage because the information density can be significantly increased in the form of multistate memory15,16. Redox switches with two or three states are very common3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, the realization of four or more than four redox states is challenging12,13,14,15,16. In order to get multistate redox switches, molecules should display multistate redox processes at a relatively low region. Otherwise, the higher or lower redox states will be quickly reduced or oxidized by the atmosphere or solvent. In addition, the potential separation between neighboring states should be large to prevent disproportionation. A third consideration is that known molecular switches are mostly based on solution state. For eventual applications, these solution-based demonstrations must be transformed into surface-confined technologies17,18,19,20. It is thus critical to take into account of a proper film-formation method during the stage of molecular design.

Recent studies have shown that polypyridyl ruthenium complexes with a Ru-C bond, namely cyclometalated ruthenium complexes, are particularly useful for the construction of molecular switches with multiple redox processes21,22. The presence of the Ru-C bond significantly decreases the Ru(III/II) potential and affords diruthenium23 or ruthenium-amine24,25,26 conjugated complexes with three redox states. These complexes are characterized by rich absorptions in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) region and potentially useful as electrochromic materials for variable optical attenuators in fiber-optic communications27,28,29. The film formation of these complexes can be realized by electropolymerization30, layer-by-layer assembly31, and self-assembly monolayers32. Recently, a cyclometalated diruthenium system bridged by a redox-active amine unit was reported by us33,34, which showed the presence of four redox states at a low potential region. We present in this contribution the synthesis and study of a star-shaped tris-cyclometalated ruthenium complex with an amine core. The synthesis is very simple and straightforward. This complex functions as a molecule switch with readily available five redox states at a low potential window. In addition, electropolymerized films of a vinyl-functionalized derivative were prepared, which were used to examine the redox switching behavior in film state.

Results

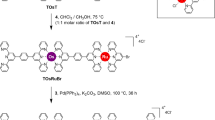

As depicted in Fig. 1, ligand 1 was synthesized through the palladium-catalyzed C-N couplings between 3,5-di(pyrid-2-yl)bromobenzene and 3,5-bis(pyrid-2-yl)aniline. The product precipitated out from the reaction mixture when the reaction was complete. After cooling to room temperature, a simple filtration and washing procedure gave ligand 1 in 66% yield, which is pure enough for the next transformation without further purification. The reaction of [Ru(tpy)Cl3] (tpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine) with 1 under microwave heating, in the presence of AgOTf and N-ethylmorpholine and followed by anion exchange using KPF6, afforded complexes 2(PF6)3 and 2(PF6)4, in a total yield of 45%. Complex 2(PF6)4 with four counter anions was the one-electron-oxidized form of 2(PF6)3. Satisfactory 1H NMR spectrum could be obtained for 2(PF6)3 in the presence of small amount of aqueous hydrazine in CD3CN, while 2(PF6)4 is paramagnetic and no distinct NMR data was obtained. Both compounds are bench stable and satisfactory microanalysis was obtained. The observed isotope distribution is in agreement with the theoretical value (See details in the Supporting Information).

Partially due to the large size of the molecule, we failed to obtain a single crystal of 2(PF6)3. Fortunately, a single crystal of 2(BPh4)3, which was produced by the anion exchange of 2(PF6)3 with NaBPh4, was obtained suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 2). The molecule is pesudo-C3 symmetric around the central amine, which has essentially a planar configuration. The three ∠CNC angle around the central amine atom is around 120° and the triarylamine unit has a three-wheel propeller configuration. The degrees of the dihedral angles between the central amine plane and each cyclometalating phenyl ring are 27.647°, 36.899°, and 43.568°, respectively. Each ruthenium component has an expected octahedral six-coordinate configuration. The terminal tpy ligand is orthogonal to the N∧C∧N cyclometalating ligand plane of the same ruthenium component. The three Ru-C bonds are 1.941(7), 1.942(6), and 1.953(6) Å in length, respectively. The Ru-N bonds around the ruthenium ion are in the range of 1.99–2.10 Å in length. The distance between each ruthenium ion and the central amine nitrogen atom is around 6.15 Å. Attempts to get a high-quality single crystal of 3(PF6)4 or 3(BPh4)4 failed at this stage.

(a) Thermal ellipsoid plot at 30% probability of the single-crystal X-ray structure of 23+. H atoms are omitted. Color code: carbon, grey; nitrogen, blue; ruthenium, magenta. (b,c) Schematic representation showing the degrees of the three ∠CNC angle around the central amine atom and the dihedral angles between the central amine plane and each cyclometalating phenyl ring.

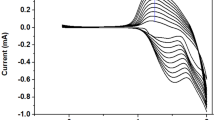

Figure 3 shows the anodic cyclic voltammogram (CV) and differential pulse voltammogram (DPV) of 2(PF6)3 in CH3CN. Four consecutive one-electron waves at +0.082, +0.31, +0.74, and +1.07 V vs Ag/AgCl are observed (annotated as E1–E4, respectively). The peak-to-peak potential difference of the oxidation and reduction of each couple is around 60~70 mV. These waves are ascribed to the stepwise oxidations of three cyclometalated ruthenium components and the central amine unit. Notable is that these four redox couples all locate at a relatively low potential region and are well-separated from each other. The potential separation between neighboring redox waves is 230, 430, and 300 mV for ΔE1−2, ΔE2−3, and ΔE3−4, respectively. This ensures a high thermodynamic stability of each redox state against proportionation. The comproportionation was calculated to be 7.9 × 103, 1.9 × 107, 1.2 × 105, respectively, by Kc = 10ΔE/59. At a further positive potential, multi-electron redox waves at +1.31 V and irreversible oxidation peaks at +1.58 V are observed (Figure S1). The previously reported amine-bridged diruthenium complex show three consecutive anodic waves at +0.21, +0.44, and +1.03 V, respectively33. This indicates that the attachment of the third ruthenium component can further decrease the E1 potential by more than 100 mV, which is important for maintaining the high stability of 23+ and 24+. The first cathodic wave of 2(PF6)3 occurs at −1.25 V, followed by adsorption/desprotion peaks at a further negative potential (Figure S1). These waves have relatively high redox potentials and are not considered for the applications as molecular switches.

As was discussed above, complex 2(PF6)3 shows four consecutive redox waves at a low potential region with large potential separation between neighboring waves. This feature makes complex 2(PF6)3 an appealing redox switch. Figure 4 shows the absorption spectral changes of 2(PF6)3 in CH3CN during the one-electron (single-), the second one-electron (double-), the third one-electron (triple-), and the forth one-electron (quadruple) oxidation with up to one, two, three, and four equiv of cerium ammonium nitrate (CAN), respectively. The one-electron-oxidized state 24+ was characterized by an intense NIR absorption band at 1590 nm. The previously isolated sample 2(PF6)4 shows exactly the same NIR absorption. Upon transforming into higher-oxidation states, the NIR absorptions of these complexes moved to 1400 nm for 25+, 1060 nm for 26+, and 740 nm for 27+, respectively. The above four step spectral changes basically can be reproduced by spectroelectrochemical measurements at a transparent indium-tin-oxide (ITO) glass electrode (Figure S2). The potentials applied for each step electrolysis correlates well with the redox processes shown in Fig. 3. These spectral changes are reversible when an opposite potential was applied, suggesting the good stability of each redox state during the redox switching process.

In addition to the NIR absorption spectra, the different redox states of 2 can be distinguished by the EPR signal. Complex 24+ shows an intense single-line EPR signal at g = 2.060 (Fig. 5a) at either rt or 77 K in frozen CH3CN. However, other redox states (23+, 25+, 26+, and 27+) are all EPR inactive. Complexes with a high oxidation state were obtained from 2(PF6)3 upon oxidation with CAN and the identities were confirmed by the NIR absorption spectra. The single-line EPR signal of 24+ suggests that it has largely an amine-associated free spin supported by three ruthenium units. A low-spin Ru(III) complex often displays an axial or rhombic EPR signal at low temperature35. Note that 2(PF6)4 is a highly stable paramagnetic amminium radical cation, and no changes occur to its NIR absorption spectrum and EPR signal after storing at ambient conditions after several months in the solid state. The topic of obtaining stable paramagnetic organic radicals have recently received intense interest due to their unique properties36,37,38,39.

The absorptions of 27+ at 740 nm are easy to understand. It is assigned to the N•+-localized transitions of triarylaminium compounds40,41. DFT calculations were performed on 24+ using UCAM-B3LYP/LANL2DZ/6-31G*/CPCM. The spin density of 24+ is distributed across the N(phenyl-Ru)3 backbone (Fig. 5b). The central amine nitrogen atom has a Mulliken spin density of 0.331, while the contribution of each ruthenium ion is 0.070, 0.071, and 0.074, respectively. Three cyclometalating phenyl rings have contributions of 0.154, 0.156, and 0.160, respectively. This suggests that the interpretation of 24+ as a ruthenium-supported triphenylaminium radical cation is appropriate. The use of B3LYP produced a more delocalized spin density distribution (Figure S3). TDDFT calculations of 24+ show that the NIR transitions are largely associated with the β spin transitions from the ruthenium-dominated highest occupied spin orbital (HOSO) and HOSO-1 to the lowest unoccupied spin orbital (LUSO) delocalized over the N(phenyl-Ru)3 backbone (Figure S4). The NIR absorptions of 25+ and 26+ could also be reproduced by TDDFT calculations (Figures S5 and S6).

The redox switching shown in Fig. 4 was performed in solution. To demonstrate the reversibility and practicality of this switching behavior, it would be necessary to obtain thin films of this complex in good quality. The relatively low solubility of the trimetallic complex in common organic solvents make the film formation by conventional spin coating unsuitable. The reductive electropolymerization method for obtaining thin films was thus used42,43,44.

Complex 3(PF6)4 with a vinyl substituent on each terminal ligand was prepared from [Ru(vtpy)Cl3] (vtpy = 4′-vinyl-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine)45 and the C3-symmetric bridging ligand 1 (Fig. 6). The reductive electropolymerization of 3(PF6)4 was smoothly executed on ITO glass electrode surface via repeatedly cathodic potential sweeps between −0.8 V and −1.7 V in CH3CN, as evidenced by the gradual and continuous increase in current (Fig. 7a). The obtained poly-3n+/ITO film shows similar four well-defined redox processes during the anodic sweep in clear electrolyte solution as have been observed for 2(PF6)4 in solution, and the peak currents are linearly dependent on the scan rate (Fig. 7b,c). The latter feature is characteristic of redox processes confined on electrode surfaces. The peak-to-peak potential separation of each redox wave is around 30 mV at a low scan rate of 20 mV/s. It increases to around 100 mV at a high scan rate of 100 mV/s. The surface coverage can be estimated by the integration of the charge under each redox wave. The thickness or surface coverage of the film can be easily controlled by changing the potential cycles during polymerization (Fig. 7d).

(a) CVs recorded during the reductive electropolymerization of 3(PF6)4 (around 0.5 mM in CH3CN) at an ITO glass electrode by 15 potential cycles between −0.8 and −1.7 V). (b) CVs of the poly-3n+/ITO film obtained in (a) at different scan rates (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mV/s, respectively). (c) Linear dependence of the peak currents of the redox wave at +0.36 V in (b) as a function of scan rate. (d) CVs of poly-3n+/ITO films obtained after 15, 30, and 45 potential cycles. The scan rate is 20 mV/s. The surface coverage is 3.0 × 10−9, 5.0 × 10−9, and 8.0 × 10−9 mol/cm2, respectively.

The FTIR spectra of the monomer complex 3(PF6)4 and the poly-3n+ sample are displayed in Figure S7. The intense peak at 840 cm−1 of 3(PF6)4 is attributed to the PF6− stretches. The signal around 1100 cm−1 of poly-3n+ is assigned to the ClO4− anions. This indicates that the anions of the obtained poly-3n+ samples are mainly ClO4−, which was incorporated from the electrolyte (Bu4NClO4) during electropolymerization. The weak peak at 960 cm−1 of 3(PF6)4 is caused by the out-of-plane deformation vibration of vinyl groups46. This peak is essentially absent in the polymer sample, which suggests that all of the three vinyl groups of the monomer are consumed during the polymerization.

Figure 8a shows the typical AFM surface morphology of the poly-3n+/ITO film. The size of islands varies from a few tens of nm to a hundred nm. The surface has a mean roughness (rms) of 6.03 nm. As measured by a scratching method (Figure S8), the film with a surface coverage of 8.0 × 10–9 mol/cm2 is around 100 nm thick. The cross-section SEM image of the film confirms a similar thickness (Fig. 8b). In addition, the SEM image suggests that the film adheres tightly to the ITO glass, which is critical for the performance of redox switching in the film state.

The poly-3n+/ITO film shows four-step redox switching as have been observed for 2(PF6)4 in solution (Figure S9). The absorption spectra and the film picture of the poly-3n+/ITO film at different redox states are shown in Fig. 9a. The film is purple, brown, chocolate, olive, and blue from poly-33+ through poly-37+, respectively. The absorption spectra in the NIR region of the five redox states of the film are significantly different. However, poly-33+ and poly-34+ display very absorption spectra in the visible region. Similar situation is observed for poly-35+ and poly-36+. This explains why the film color does not change significantly among these redox states. The spectral changes recorded during the electrochemical switching are fully reversible. In particular, the film displays a high contrast ratio (ΔT%) of 63% at the fiber communication wavelength (1550 nm) during the double-potential-step chronoamperometry measurements between −0.1 and +0.3 V (Fig. 9b,c), which is much higher with respect to that of the electrochromism based on a recently reported diruthenium complex (ΔT%: around 30∼40%)33. To the best of our knowledge, this is also one of the highest contrast ratios ever achieved at the optic telecommunication wavelength on the basis of molecular electrochromic materials29,47,48,49,50. The coloration efficiency (CE) of for the above process was calculated to be 250 cm2/C according to the equation CE(λ) = ΔOD/Qd, where ΔOD = log[Tb/Tc], OD is optical density, Qd is the injected/ejected charge density (C/cm2), and Tb and Tc are the transmittance in the bleached and colored states at 1550 nm. The response time for the contrast ratio to reach over 90% of its maximum is around 50 s (Figure S10). This response time is much longer with respect to the NIR electrochromism based on our previously reported diruthenium complexes (around 5 s)21,33. One possible reason is that the currently used triruthenium monomer contains three vinyl groups and the resulting poly-3n+ film has a higher degree of cross-linking and chain entanglement relative to the previously reported diruthenium monomers with two vinyl groups. In this sense, the anion transport to compensate the charge changes of the polymer backbones of the triruthenium film will be severely hindered, leading to a long response time.

(a) Absorption spectra and film picture of the poly–3n+/ITO film at different redox states (Γ = 3.0 × 10−9 mol/cm2). (b) Current assumption and (c) transmittance changes monitored at λ = 1550 nm as a function of time during the electrochromic switching of the poly–3n+/ITO film (Γ = 2.0 × 10−8 mol/cm2) between −0.1 and +0.3 V in 0.1 M Bu4NClO4/CH3CN. The interval is 65 s.

In addition to the first-step redox switching, the electrochromism of the poly-3n+/ITO film at 1180 nm switched between −0.1 and +0.7 V (the second oxidation), 1150 nm switched between −0.1 and +1.0 V (the third oxidation), and 780 nm switched between −0.1 and +1.4 V (the forth oxidation) were examined (Figure S11). The second and third oxidation step show good switching cycling reversibility, with a contrast ratio of around 60% being achieved for both cases. However, reversibility of the forth oxidation step is poor. After 25 cycles of redox switching between −0.1 and +1.4 V, the contrast ratio decreased from 42% to 30% (Figure S11c). In addition, the optical memory of the different redox states of the poly-3n+/ITO film was examined (Figure S12). The poly-33+ and poly-34+ are two bench-stable states. The poly-35+ and poly-36+ states also have long optical memory time. For instance, when the polymer film was oxidized to poly-35+ by a potential at +0.7 V, the transmittance at 1180 nm changed slightly from 40% to 55% after 100 min after the potential was switched off. Similar situation is observed for the poly-36+ state. However, the optical stability of poly-37+ is rather poor. The optical memory time of poly-37+ is only around 5 min. The high oxidation state of 37+ makes it easily reduced by solvents or atmosphere.

In summary, we have successfully prepared a star-shaped tris-cyclometalated ruthenium complex with a redox-active triarylamine core. Interestingly, the one-electron-oxidized form was isolated as a stable paramagnetic compound, which is best described as a ruthenium-stabilized triphenylaminium radical cation as supported by EPR and DFT analysis. This complex and the electropolymerized films of the vinyl-functionalized complex display four consecutive one-electron anodic redox couples at low potentials, functioning as a molecular redox switch with up to five well-separated states. NIR absorptions and EPR signal were used as the output signals to distinguish different redox states. This makes the complex attractive for high-density information storage15,16. In addition, a high contrast ratio of 63% was achieved at the optic telecommunication wavelength (1550 nm). This is one of the highest contrast ratios ever achieved at this wavelength on the basis of molecular electrochromic materials, and it is potentially useful as active materials for variable optical attenuators in optic telecommunication29,47,48,49,50.

Methods

Spectroscopic Measurements

Absorption spectra were recorded using a PE Lambda 750 UV/vis/NIR spectrophotometer at room temperature. Spectroelectrochemical measurements and electrochromic studies were performed in a thin layer cell (optical length = 0.2 cm), in which an ITO glass electrode (<10 Ω/square) or the ploy-3n+/ITO film was set as the working electrode in 0.1 M Bu4NClO4/CH3CN. A platinum wire and Ag/AgCl in saturated aqueous NaCl solution was used as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The cell was put into the spectrophotometer to monitor spectral changes during electrolysis.

Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical measurements were taken using a CHI 660D potentiostat with one-compartment electrochemical cell under an atmosphere of nitrogen. All measurements were carried out in 0.1 M Bu4NClO4 in CH3CN. The working electrode was a glassy carbon with a diameter of 3 mm. The electrode was polished prior to use with 0.05 μm alumina and rinsed thoroughly with water and acetone. A large area platinum wire was used as the counter electrode. All potentials are referenced to a Ag/AgCl electrode in saturated aqueous NaCl without compensation for the liquid junction potential. Electropolymerization experiments were carried out in three compartment electrochemical cell with ITO glass (<10 Ω/square) as the working electrode. The ITO glass was cleaned by successive sonication in deionized water, isopropanol and acetone for 10 min, followed by drying with N2 gas. The obtained film has a typical size of 1.0 cm × 0.8 cm.

X-ray Crystallography

The X-ray diffraction data were collected using a Rigaku Saturn 724 diffractometer on a rotating anode (Mo-K radiation, 0.71073 Å) at 173 K. The structure was solved by the direct method using SHELXS-97 and refined with Olex2. Crystallographic data for 2(BPh4)3·CH2Cl2 (CCDC 1480175): C93H63N16Ru3·3(BC24H20)·CH2Cl2, M = 2750.35, monoclinic, space group P 1 21/n 1, a = 19.981(4), b = 31.846(5), c = 26.234(5) Ǻ, α = 90°, β = 107.802(2)°, γ = 90°, U = 15894(5) Ǻ3, T = 173 K, Z = 4, 130185 reflections measured, radiation type MoK\a, radiation wavelength 0.71073 Ǻ, final R indices R1 = 0.1226, wR2 = 0.2660, R indices (all data) R1 = 0.1348, wR2 = 0.2734.

EPR Measurements

EPR measurements were performed on a Bruker ELEXSYS E500-10/12 spectrometer at 77 K in frozen CH3CN. The spectrometer frequency is 9.7 × 109 Hz.

AFM Images

AFM images were taken using a Nanoscope III A multimode atomic force microscope (Vecco Inc., USA) in the ScanAsyst mode in air with a scan speed of 1 Hz.

SEM Images

SEM images were taken using a JEOL S-4300 field emission scanning microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV. Prior to measurement, an ultrathin conductive Au coating was deposited on the top of the polymeric films on ITO glass electrodes.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Tang, J.-H. et al. Multistate Redox Switching and Near-Infrared Electrochromism Based on a Star-Shaped Triruthenium Complex with a Triarylamine Core. Sci. Rep. 6, 35253; doi: 10.1038/srep35253 (2016).

References

Feringa, B. L. Molecular Switches (Wile-VCH, 2001).

Hirao, T. Redox Systems Under Nano-Space Control (Springer, 2006).

Lindsey, J. S. & Bocian, D. F. Molecules for charge-based information storage. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 638–650 (2011).

Terada, K. et al. Memory effects in Molecular Films of Free-Standing Rod-Shaped Ruthenium Complexes on an Electrode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6287–6291 (2011).

Simao, C. et al. A robust molecular platform for non-volatile memory devices with optical and magnetic responses. Nat. Chem. 3, 359–364 (2011).

Mortimer, R. J. Rosseinsky, D. R. & Monk, P. M. S. Electrochromic Materials and Devices (Wile-VCH, 2015).

Beaujuge, P. M. & Reynolds, J. R. Color control in π-conjugated organic polymers for use in electrochromic devices. Chem. Rev. 110, 268–320 (2010).

Higuchi, M. Stimuli-responsive metallo-supramolecular polymer films: design, synthesis and device fabrication. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 9331–9341 (2014).

Lim, H. et al. NIR electrofluorochromic properties of aza-boron-dipyrromethane dyes. Sci. Rep. 6, 18867 (2016).

Sakamoto, R. et al. π-Conjugated bis(terpyridine)metal complex molecular wires. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7698–7714 (2015).

Sakamaki, D. et al. A polymacrocyclic oligoarylamine with a pseudobeltane motif: towords a cyclindrical multispin system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12776–12781 (2012).

Kaim, W. & Lahiri, G. K. Unconventional mixed-valent complexes of ruthenium and osmium. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 46, 1778–1796 (2007).

Mondal, P. et al. Noninnocence of indigo: dehydroindigo anions as bridging electron-donor ligands in diruthenium complexes. Inorg. Chem. 55, 3105–3116 (2016).

Tang, J.-H. et al. Ruthenium-amine conjugated organometallic materials for multistate near-IR electrochromism and information storage. Chem. Rec. 16, 754–767 (2016).

de Ruiter et al. Electrically addressable multistate volatile memory with flip-flop and flip-flap-flop logic circuits on a solid support. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4780–4783 (2010).

Simao, C. et al. A three-state surface-confined molecular switch with multiple channel outputs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13256–13259 (2011).

Winter, A., Hoeppener, S., Newkome, G. R. & Schubert, U. S. Terpyridine-functionalized surfaces: redox-active, switchable, and electroactive nanoarchitectures. Adv. Mater. 23, 3484–3498 (2011).

de Ruiter, G. & van der Boom, M. E. Surface-confined assemblies and polymers for molecular logic. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 563–573 (2011).

Mas-Torrent, M. Rovira, C. & Veciana, J. Surface-confined electroactive molecules for multistate charge storage information. Adv. Mater. 25, 462–468 (2013).

Poppenberg, J. et al. Programmable multilayers of nanometer-sized macrocycles on solid support and stimuli-controlled on-surface pesudorotaxane formation. Chem. Sci. 4, 3131–3139 (2013).

Yao, C.-J. et al. Near-IR electrochromism in electropolymerized films of a biscyclometalated ruthenium complex bridged by 1,2,4,5-tetra(2-pyridyl)benzene. 133, 20720–20723 (2011).

Nagashima, T. et al. Photoresponsive molecular memory films composed of sequentially assembled heterolayers containing ruthenium complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 1658–1667 (2016).

Zhong, Y.-W. et al. Electronic coupling in cyclometalated ruthenium complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 312, 22–40 (2016).

Shen, J.-J. & Zhong, Y.-W. Long-range ruthenium-amine electronic communication through the para-oligophenylene wire. Sci. Rep. 5, 13835 (2015).

Grelaud, G. et al. Multistate redox-active metalated triarylamines. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 145, 65–75 (2012).

Polit, W. et al. Vinylruthenium-triarylamine conjugates as electroswitchable polyelectrochromic NIR dyes. Bioinorg. React. Mech. 8, 85–105 (2012).

Kaim, W. Concepts for metal complex chromophores absorbing in the near infrared. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 2503–2513 (2011).

Qian, G. & Wang, Z. Y. Near-infrared organic compounds and emerging applications. Chem. Asian J. 5, 1006–1029 (2010).

Qi. Y.-H. et al. Electrochromic ruthenium complex materials for optical attenuation. Opt. Mater. 21, 255–263 (2002).

Friebe, C. et al. Metal-containing polymers via electropolymerization. Adv. Mater. 24, 332–345 (2012).

Tieke, B. Coordinative supramolecular assembly of electrochromic thin films. Curr. Opin. Coll. Interf. Sci. 16, 499–507 (2011).

Cui, B.-B. Zhong, Y.-W. & Yao, J. Three-state near-infrared electrochromism at the molecular scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4058–4061 (2015).

Cui, B.-B. et al. A molecular platform for multistate near-infrared electrochromism and flip-flop, flip-flap-flop, and ternary memory. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9192–9197 (2015).

Tang, J.-H. et al. Transition from a metal-localized mixed-valence compound to a fully delocalized and bridge-biased electrophore in a ruthenium-amine-ruthenium tricenter system. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 10341–10345 (2016).

Patra, S. et al. Separating innocence and non-innocence of ligands and metals in complex [(L)Ru(acac)2]n (n = −1, 0, +1; L = o-iminoquinone or o-iminothioquinone). Inorg. Chem. 42, 6469–6473 (2003).

Su, Y. et al. Nitrogen analogues of Thiele’s hydrocarbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 1634–1637 (2015).

Hicks, R. G. What’s new in stable radical chemistry? Org. Biomol. Chem. 5, 1321–1338 (2007).

Ratera, I. & Veciana, J. Playing with organic radicals as building blocks for functional molecular materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 303–349 (2012).

Menichetti, S. et al. Thia-bridged triarylamine heterohelicene radical cations as redox-driven molecular switches. Chem. Commun. 51, 11452–11454 (2015).

Lambert, C. & Nöll, G. The class II/III transition in triarylamine redox systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 8434–8442 (1999).

Sreenath, K. et al. Cu(II) mediated generation and spectroscopic study of the tris(4-anisyl)amine radical cation and dication. Unusually shielded chemical shifts in the dication. Org. Lett. 13, 1134–1137 (2011).

Zhong, Y.-W., Yao, C.-J. & Nie, H.-J. Electropolymerization films of vinyl-substituted polypyridine complexes: synthesis, characterization, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257, 1357–1372 (2013).

Potts, K. T. et al. 4-Vinyl, 6-vinyl, and 4′-vinyl-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridinyl ligands: their synthesis and the electrochemistry of their transition-metal coordination complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 3961–3967 (1987).

Lapides, A. M. et al. Stabilization of a ruthenium(II) polypyridyl dye on nanocrystalline TiO2 by an electropolymerized overlayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15450–15458 (2013).

Nie, H.-J. et al. Synthesis of vinyl-substituted polypyridyl ligands through Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling of potassium vinyltrifluoroborate with bromopolypyridines. J. Org. Chem. 76, 4771–4775 (2011).

Rege, R. V. et al. Validation of infrared spectroscopy for assessment of vinyl polymers of bile-pigment gallstones. Biochem. J. 224, 871–876 (1984).

Qi, Y. & Wang, Z. Y. Dendritic mixed-valence dinuclear ruthenium complexes for optical attenuation at telecommunication wavelengths. Macromolecules 36, 3146–3151 (2003).

Ward, M. D. Near-infrared electrochromic materials for optical attenuation based on transition-metal coordination complexes. J. Solid State Electrochem. 9, 778–787 (2003).

Dyer, A. L., Grenier, C. R. G. & Reynolds, J. R. A Poly(3,4-alkylenedioxythiophene) electrochromic variable optical attenuator with near-infrared reflectivity tuned independently of the visible region. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 1480–1486 (2007).

Wang, S. et al. Near-infrared electrochromic and electroluminescent polymers containing pendant ruthenium complex groups. Macromolecules 39, 7502–7507 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 21271176, 21472196, 21521062, and 21501183), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant 2012YQ120060), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant XDB 12010400) for funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-W.Z. planned and supervised the project; J.-H.T. conducted all experiments; Y.-Q.H. and Z.-L.G. contributed to the synthesis work; J.-Y.S. contributed to the DFT calculations; all authors analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, JH., He, YQ., Shao, JY. et al. Multistate Redox Switching and Near-Infrared Electrochromism Based on a Star-Shaped Triruthenium Complex with a Triarylamine Core. Sci Rep 6, 35253 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35253

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35253

- Springer Nature Limited